Lecturing Effectively in The University Classroom

Diunggah oleh

Eggy PascualDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Lecturing Effectively in The University Classroom

Diunggah oleh

Eggy PascualHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Lecturing Effectively in the University Classroom As long as class sizes continue to increase and university budgets tighten, lecturing

will remain a dominant teaching method (Perry in Perry & Smart, 1997; Brown & Race, 2002). Knowing how to lecture well, therefore, is a crucial skill to master. Effective lecturing is characterized by enthusiasm and expressiveness, clarity, and interaction (Murray in Perry & Smart, 1997). Consider using the tips below to introduce students toand stimulate their enthusiasm about your course material. Structuring the Lecture Clearly

Show students the big picture. Explain how the lecture relates to previously-learned material and the course themes and goals in general. Begin the class with a short review of the key points from last class, and end with a preview of the topics for next class (along with a reminder about any readings or assignments to be completed). Tell them what youre going to say, say it, then tell them what youve just said. Before discussing the days topics, provide an overview of what will be discussed. After covering the topics, end with a restatement of the key points. When speaking, repeat yourself to an extent that would be redundant in writing to facilitate student note-taking. Keep the lecture outline visible for students. Write it on a corner of the blackboard or leave it up on an overhead. Return to the outline periodically to show your progress through the material and to reinforce key points. Make explicit transitions between topics with mini-summaries. Link current material to previously-learned content and future lectures. Be explicit about how one topic connects to the next, or ask your students to explain the connections. By linking new material to previously-learned content, you help students understand and organize this new information in their minds. Cover only a few main points in each lecture. Plan to cover only three or four points in a fifty-minute lecture and four or five points in a seventy-five-minute class. Select key points that introduce, complement, and/or clarify the course readings, assignments, and goals. Focus on presenting central points or general themes that tie together as many topics as possible; students will be able to associate details with these main points on their own. Avoid merely repeating the course readings; instead, elaborate on this content using new examples and sample exercises or problems. For more information about selecting and organizing content, see the Course Content Selection and Organization CTE Teaching Tip.

Preparing your Notes

Avoid writing out a complete lecture script. A script is too time-consuming to prepare, and it will prevent you from maintaining eye contact with the students. As you read, your voice will project downward, and you will appear disengaged from the class. Your ability to be spontaneous will be hindered. Also avoid using visual aids as your notes; your

reading from an overhead or computer screen will not keep the students engaged, since your visual focus still will not be on them.

Do prepare some notes. Experiment to find out what kind of notes work best for you, e.g., detailed outline, list of major points, tree diagram. Your notes should include key definitions, proofs, solved problems, examples and analogies. If you think you might get nervous in front of a large class, make sure you know exactly what you are going to say at the beginning of class. Be flexible when following your notes. Watch students level of interest and confusion to determine how much time to spend on a topic and what level of explication is required. Your notes should be flexible enough to let you adjust the depth and order of the content based on students feedback. Your notes are there if needed, but the lecture should arise out of your interaction with the students, not the notes themselves. Include delivery notes. Use wide margins so you can add notes about audio-visual aids, questions to ask students, last-minute examples, and instructions for hands-on activities.

Keeping Students Engaged

Design your lecture in ten- to fifteen-minute blocks. Adult attention spans average ten to twenty minutes, so change pace every fifteen minutes or so to relieve monotony and recapture students interest. Intersperse mini-lectures with discussions or other activities. For suggestions about alternatives to lecturing, see the CTE Teaching Tip Varying Your Teaching Activities: 9 Alternatives to Lecturing. Actively involve students in their learning. Ask them to help you demonstrate an analogy to explain an abstract concept. Give them practice problems or a writing exercise to do on their own or in pairs. Have a brainstorming session with the entire class or in small groups. Show a video clip prefaced by your instructions about what to look for. Give a multiple choice quiz. Have a question and answer session. Prepare questions beforehand that promote class discussion and reinforce key concepts. Use such activities to regain student attention and deepen their learning. The CTE Teaching Tip Active Learning Activities has more suggestions for actively involving students in their learning. Be sure to stress why the lecture material is valuable for the students. Relate the content to students interests, knowledge, experiences, and needs as much as possible. Use metaphors, analogies, and examples that appeal to the students and will help them understand the material. Making the material relevant is critical for keeping students attentive, and it will help them retain the information. State your key points as learning objectives for the students. Share these objectives with your students: By the end of the class, you will be able to . State the objectives as concretely as possible, using action verbs (e.g., draw, solve, explain) rather than vague verbs (e.g., learn, understand, know). After you have prepared the lecture and again after you have delivered it, check that you have in fact accomplished these objectives.

Use students questions. While preparing the lecture, anticipate students questions. Incorporate the answers into your lecture, or introduce an activity that allows students to discover the answers for themselves. During the lecture, use students responses and questions as jumping-off places for your next point or to begin a spontaneous discussion. Attend to students feedback about how the lecture is going. Watch their nonverbal cues (yawns, chairs shuffling, whispers, glazed looks), or ask for their feedback informally or formally. Just because you are speaking does not mean that they are attentively listening.

Delivering the Lecture

Check out your classroom in advance. Familiarize yourself with the layout of the desks and the front of the classroom. Decide where you will stand and how you will move from one place to another. Find out whether the classroom has audio-visual equipment or whether you will have to request it from the Audio Visual Centre. Practice your lecture beforehand. For your first few lectures, practice to ensure that you have an appropri ate amount of material and activities for the time available. Then record your timings after class so you can discern the pacing of your style. Students questions and learning activities can take up to 50% more time than you may first think. Take along a bottle of water. The water will soothe a sore or dry throat. Taking a sip is also a good way to buy thinking time before responding to a student question. Maintain regular eye contact with your students. By doing so, you create connections with them, are able to gauge their note-taking, and discourage distracting class noise. Use a conversational tone. Think of the lecture as an opportunity to speak with the students, not to or at them. Convey your enthusiasm for the material and the students. Vary your vocal speed and pitch, as well as your facial expressions. Smile often. Consider using humour when appropriate. Ask the students periodically if they can hear and see everything. Make changes to your volume and visual aids as necessary. Move around the room, and use natural gestures. This movement is especially important for engaging large classes. Changes help to refocus students attention, but remember to move with purpose so you avoid distracting your students. Encourage students to take notes. The process of writing notes helps them remember the lecture content and stay attentive to whats going on. To help students make good notes, provide a clear structure for the lecture, and use a pace that allows them to keep up (remember not to rush when using pre-prepared visual aids). Rather than writing extensive notes that students must copy word for word, write key terms on the board or slides to facilitate students own processing of the information, or provide skeletal course

notes for the students to annotate. Pause regularly so that students can ask for clarification.

Interact with your students to create positive rapport with them. Arrive at class early so that you can welcome students. Address them by name as much as possible. And plan to stay after class to chat with students and answer their questions.

Using Visual Aids (blackboard, overheads or computer presentations)

Use visual aids to stimulate and focus students attention. Multimedia aids using sound, colour, and/or animations have an even greater power to attract and maintain students attention, particularly in large classes where the impersonal situation makes students feel less involved. Visual aids should be a support for, not the focus of, your lecture. They also should not replace your personal interaction with the students. Make each visual count. If you are using overheads or PowerPoint, aim for twelve to twenty slides for a fifty-minute lecture. Be conscious of speeding through the slides and/or overloading students with contentcommon problems with these types of media. Reveal visual information gradually rather than all at once. This keeps students focusing on your oral development of each point, instead of rushing to copy down the material. Alternately, you could show all the points, then go back to explain each one. Consider creating visual aids during the lecture. Solving problems, showing processes, or building models in real time is often clearer for students than seeing completed work. You can also create visuals to reflect the outcomes of interactive exercises, thereby validating the students input. The act of writing also helps you to pace the lecture appropriately. Write down key words and names. Students will try to write down everything they see. If information does not need to be copied down, mention that to the students, or consider whether it is important enough to include in the first place. Consider providing handouts that give an outline of the lecture material for students to annotate. Check the equipment before class. Electronic equipment can break down or malfunction, so have an alternate plan ready. Equipment problems will negatively affect your credibility, even if they are beyond your control. Make sure, too, that you know how to operate the equipment.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Performance Requirements For Organic Coatings Applied To Under Hood and Chassis ComponentsDokumen31 halamanPerformance Requirements For Organic Coatings Applied To Under Hood and Chassis ComponentsIBR100% (2)

- Car Loan ProposalDokumen6 halamanCar Loan ProposalRolly Acuna100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Madagascar's Unique Wildlife in DangerDokumen2 halamanMadagascar's Unique Wildlife in DangerfranciscogarridoBelum ada peringkat

- Ariel Enfeites para CabeloDokumen2 halamanAriel Enfeites para CabeloKaren Reimer100% (2)

- Prostate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedDokumen1 halamanProstate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Prostate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedDokumen1 halamanProstate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Prostate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedDokumen1 halamanProstate Cancer Risk Factors & Stages ExplainedEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Medical Surgical Nursing Nclex Questions Endo2Dokumen9 halamanMedical Surgical Nursing Nclex Questions Endo2dee_day_8Belum ada peringkat

- Rizal as an inventor and naturalistDokumen3 halamanRizal as an inventor and naturalistEggy Pascual100% (3)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- MMS-TRG-OP-02F3 Narrative ReportDokumen14 halamanMMS-TRG-OP-02F3 Narrative ReportCh Ma100% (1)

- 2015 Masonry Codes and Specifications Compilation, MCAA StoreDokumen1 halaman2015 Masonry Codes and Specifications Compilation, MCAA StoreMuhammad MurtazaBelum ada peringkat

- Eun 9e International Financial Management PPT CH01 AccessibleDokumen29 halamanEun 9e International Financial Management PPT CH01 AccessibleDao Dang Khoa FUG CTBelum ada peringkat

- PDF. Art Appre - Module 1Dokumen36 halamanPDF. Art Appre - Module 1marvin fajardoBelum ada peringkat

- Concepts of Cavity Prep PDFDokumen92 halamanConcepts of Cavity Prep PDFChaithra Shree0% (1)

- Emergency Trolley ContentsDokumen28 halamanEmergency Trolley ContentsEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Philippine TVET System ExplainedDokumen18 halamanPhilippine TVET System ExplainedKiril Van Abid Aguilar100% (1)

- D. Bikinaitė. Stress and Coping PPPDokumen15 halamanD. Bikinaitė. Stress and Coping PPPEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Toyota Umbrella Toyota Mug: (Globe) (SUN) (Smart)Dokumen1 halamanToyota Umbrella Toyota Mug: (Globe) (SUN) (Smart)Eggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Eye Ear DrugsDokumen5 halamanEye Ear DrugsEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Butching ReviewerDokumen371 halamanButching ReviewerEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Quiz NutritionDokumen6 halamanQuiz NutritionEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Epilepsy CaseDokumen0 halamanEpilepsy CaseEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Converstion TableDokumen4 halamanConverstion TableEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- CPR Facts and Statistics: Media Contact: Tagni Mcrae, 214-706-1383 orDokumen1 halamanCPR Facts and Statistics: Media Contact: Tagni Mcrae, 214-706-1383 orEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Case 1 PediatricsDokumen5 halamanCase 1 PediatricsEggy Pascual0% (1)

- First Aid KitDokumen1 halamanFirst Aid KitEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Rle Ncm106 Abg InterpretationDokumen12 halamanRle Ncm106 Abg InterpretationEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Fundamamcruz 1Dokumen6 halamanFundamamcruz 1Eggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

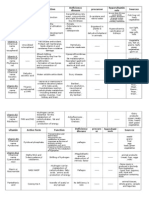

- Concept Alloted Time Dates Time Faculty PrelimsDokumen1 halamanConcept Alloted Time Dates Time Faculty PrelimsEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology of Breast Cancer: Predisposing Factors, Cell Changes, SymptomsDokumen1 halamanPathophysiology of Breast Cancer: Predisposing Factors, Cell Changes, SymptomsEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Vitamin NotesDokumen3 halamanVitamin NotesEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Itunes DiagnosticsDokumen1 halamanItunes DiagnosticsEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Fetal CirculationDokumen1 halamanFetal CirculationEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Oven Do's and Dont'sDokumen7 halamanOven Do's and Dont'sEggy Pascual100% (1)

- Overview of AnatomyendoDokumen38 halamanOverview of AnatomyendoEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Baked Ham and Cheese Omelet RollDokumen5 halamanBaked Ham and Cheese Omelet RollEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- 8 Common Charting Mistakes To Avoi1aDokumen4 halaman8 Common Charting Mistakes To Avoi1aEggy PascualBelum ada peringkat

- Alberta AwdNomineeDocs Case Circle BestMagazine NewTrailSpring2016Dokumen35 halamanAlberta AwdNomineeDocs Case Circle BestMagazine NewTrailSpring2016LucasBelum ada peringkat

- 02-Procedures & DocumentationDokumen29 halaman02-Procedures & DocumentationIYAMUREMYE EMMANUELBelum ada peringkat

- Silent SpringDokumen28 halamanSilent Springjmac1212Belum ada peringkat

- 2006 - Bykovskii - JPP22 (6) Continuous Spin DetonationsDokumen13 halaman2006 - Bykovskii - JPP22 (6) Continuous Spin DetonationsLiwei zhangBelum ada peringkat

- PSE Inc. V CA G.R. No. 125469, Oct 27, 1997Dokumen7 halamanPSE Inc. V CA G.R. No. 125469, Oct 27, 1997mae ann rodolfoBelum ada peringkat

- GUCR Elections Information 2017-2018Dokumen10 halamanGUCR Elections Information 2017-2018Alexandra WilliamsBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 018Dokumen12 halamanChapter 018api-281340024Belum ada peringkat

- Flotect Vane Operated Flow Switch: Magnetic Linkage, UL ApprovedDokumen1 halamanFlotect Vane Operated Flow Switch: Magnetic Linkage, UL ApprovedLuis GonzálezBelum ada peringkat

- MASM Tutorial PDFDokumen10 halamanMASM Tutorial PDFShashankDwivediBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1 Intro - LatinDokumen11 halamanLesson 1 Intro - LatinJohnny NguyenBelum ada peringkat

- Application of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisDokumen21 halamanApplication of Neutralization Titrations for Acid-Base AnalysisAdrian NavarraBelum ada peringkat

- Ramesh Dargond Shine Commerce Classes NotesDokumen11 halamanRamesh Dargond Shine Commerce Classes NotesRajath KumarBelum ada peringkat

- PDFDokumen2 halamanPDFJahi100% (3)

- GST Project ReportDokumen29 halamanGST Project ReportHENA KHANBelum ada peringkat

- Mendoza CasesDokumen66 halamanMendoza Casespoiuytrewq9115Belum ada peringkat

- Redminote5 Invoice PDFDokumen1 halamanRedminote5 Invoice PDFvelmurug_balaBelum ada peringkat

- Junior Instructor (Computer Operator & Programming Assistant) - Kerala PSC Blog - PSC Exam Questions and AnswersDokumen13 halamanJunior Instructor (Computer Operator & Programming Assistant) - Kerala PSC Blog - PSC Exam Questions and AnswersDrAjay Singh100% (1)

- Sarawak Energy FormDokumen2 halamanSarawak Energy FormIvy TayBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 3 Test A Test (Z Widoczną Punktacją)Dokumen4 halamanUnit 3 Test A Test (Z Widoczną Punktacją)Kinga WojtasBelum ada peringkat

- The Experience of God Being Consciousness BlissDokumen376 halamanThe Experience of God Being Consciousness BlissVivian Hyppolito100% (6)

- Design and Implementation of Land and Property Ownership Management System in Urban AreasDokumen82 halamanDesign and Implementation of Land and Property Ownership Management System in Urban AreasugochukwuBelum ada peringkat

- HSG Anh 9 Thanh Thuy 2 (2018-2019) .Dokumen8 halamanHSG Anh 9 Thanh Thuy 2 (2018-2019) .Huệ MẫnBelum ada peringkat