Smart Growth

Diunggah oleh

LTE002Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Smart Growth

Diunggah oleh

LTE002Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Smart Growth in New Zealand and Australia A Tale of Two Cities

Amanda Raleigh BSc (Hons) MURP MRAPI (Senior Planner GHD Australia) Bruce Harland BTP (Senior Environmental Policy Planner Manukau City Council, New Zealand) Greg Osborne BTP MNZPI (Planning Manager GHD New Zealand) Note: The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of Manukau City Council or GHD Limited

April 2002

____________________________________________________________________________

Contents

1. Introduction ........................................................................................... 1 2. The Regional Policy Framework : Sydney and Auckland......................... 1 3. What Is Smart Growth?................................................................................ 2 4. How Is The Smart Growth Concept Being Made To Work In The U.S.A?............................................................................................................... 3 5. Is Smart Growth Achievable And What Are The Challenges Planners Face In Achieving The Vision?........................................................................ 4

Appendix

Case Studies

S/51/0101200

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

SMART GROWTH IN NEW ZEALAND AND AUSTRALIA: A TALE OF TWO CITIES

1. Introduction A central theme of this conference is the way in which planners are grappling with the issues of the built environment. These include: improving urban amenity, managing urban growth and creating sustainable communities. The conference provides a unique opportunity to compare approaches to these universal questions in our remarkably similar yet distinct antipodean societies. The authors of this paper particularly want to exploit this opportunity in the context of what has been termed smart growth in North America; the principles of which are being currently applied to planning on both sides of the Tasman. The authors have particular experience in applying these principles in cities within Australia and New Zealands largest metropolitan regions: Sydney and Auckland. The two cities which are the subject of this paper are Liverpool City in Sydneys South West and Manukau City in Aucklands South. In particular, the case studies in this paper focus on the application of smart growth principles in the Greenfield area of the Hoxton Park Release Corridor in Liverpool and the Flat Bush Structure Plan Area in Manukau City. Both areas are of similar size (1500/1700 ha) and ultimate population (40,000 50,000 residents). As such this topic presents a unique opportunity to explore the similarities and differences in planning approach to a remarkably similar set of circumstances and challenges on both sides of the Tasman. The paper will compare the respective regional policy frameworks and identify the key elements of the Smart Growth concept. By reference to the case studies, the paper will discuss the key challenges that planners face in implementing Smart Growth Plans in both countries and by way of comparison will identify how the concept is being made to work in the USA. 2. The Regional Policy Framework : Sydney and Auckland The Sydney region houses approximately 4 million people. The regions population has been growing recently at an average of just over 1% or 42,000 each year. On current projections 500,000 new homes will be required in the next 20 30 years. Despite having a reasonably well-developed and well patronised public transit system, (which would be the envy of most Auckland planners) increased car usage is outstripping population growth. This is partly because an increasing proportion of the regions population is living in the outer suburbs where public transport is less available. In 1998 Planning NSW (previously known as the NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning or DUAP) produced a document called Shaping Our Cities. This document provides the broad framework of planning directions for the Greater Metropolitan Region of New South Wales. It contains the following key planning principles. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Manage the supply of new and redeveloped housing so as to create a compact urban structure with choice in home type and affordability throughout each part of our cities. Identify and create opportunities for employment and business growth in locations that support access by public transport and minimise conflict with other uses. Enhance opportunities for walking, cycling and using public transport and contain the growth of travel demand in all land use and development decisions. Improve the design and quality of the urban environment by requiring good architecture, protecting our built heritage and building a well- located, safe and useable public domain. Protect and improve our natural and cultural environments so as to sustain biological, water and air resources, to conserve Aboriginal heritage and to enhance our enjoyment of parklands. Manage the planning system efficiently, provide for consultation and encourage investment, job creation and business confidence.

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

Of relevance to this paper, there is an emphasis on making efficient use of new residential release areas (an average gross density of 15 dwellings per hectare is specified) and ensuring that they are provided with public transport links and are conducive to safe walking and cycling. The Auckland Region is home to 1.2 million people and its growth rate over the next 50 years is expected to average 20,000 per year. The Auckland Regional Council has led the formulation of Regional Growth Strategy which proposes that around 700,000 dwellings will be required to house a potential population of 2 million by 2050. This means that an additional 355,000 dwellings are required over the next 50 years and the strategy proposes that up to 70% of future new dwellings should be located within the existing metropolitan area and that green field areas would accommodate at least 5% of all new dwellings in new nodal centre intensification areas. By 2050 up to 30% of the Regions population would live in intensive housing forms such as low rise apartments, terrace houses and town houses. Key desired regional outcomes are stated to be: 1. 2. 3. 4. Sustainable use of resources more efficiency in use of natural and physical resources including urban land, infrastructure and energy; Maximising access and transport efficiency; Improved housing choice/affordability;: Higher quality urban amenity.

3.

What Is Smart Growth? Who can oppose smart growth since the opposite is dumb growth? While simplistically, smart growth is simply an appealing term to apply to principles which seek to avoid poorly planned suburban sprawl, it has attained a committed following in North America. The Smart Growth movement has embraced and repackaged other planning concepts such as ecologically sustainable development, new urbanism , transit oriented development and sustainable/liveable communities into a broader policy mix which includes regulatory and economic instruments which can be directed at obtaining a better or smarter environment. Smart Growth America (a coalition of over 50 agencies promoting Smart Growth in the U.S.) define Smart Growth as growth that protects open space, revitalises neighbourhoods, makes housing more affordable and improves community quality of life. The six outcomes that Smart Growth seeks to achieve are: 1. Neighbourhood liveability neighbourhoods should be safe, convenient, attractive and affordable. Achieving just one or a few of these quantities at the expense of the others is not good enough all need to be achieved. Better access, less traffic through mixed land use, clustered development and the provision of multiple transportation choices. Thriving cities, suburbs and towns by guiding development to already built up areas first. Shared benefits balanced communities with plentiful employment, educational and healthcare opportunities mean residents have equal opportunities to participate in their local economy. Lower costs, lower taxes (or rates) taking advantage of existing infrastructure keeps taxes (rates) down and convenient public transit reduces personal expenditure on transportation. Keeping open space open by focusing development in existing urban areas natural resources and values are protected.

2. 3. 4. 5. 6.

Smart Growth America advocates ten techniques for a smart growth plan: 1. Mix land uses single use districts make life less convenient and require more driving. Mixed use developments can create ready-made markets for retail businesses and make public transit feasible.

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

2.

Encourage growth in existing communities to take advantage of existing community assets - from public open space to schools to transit systems public investments should focus on getting the most out of what weve already built. Create a range of housing opportunities - different demographic and socioeconomic groups require different types of housing. Foster walkable, finely grained neighbourhoods places that offer not just the opportunity to walk but something to walk to - whether its a corner store, a school or a transit stop. Neighbours can get to know each other and not just each others cars. Promote distinctive, attractive communities with a strong sense of place, including the rehabilitation and use of historic buildings - the things that make each place special should be celebrated and protected. Preserve open space, farmland and critical environmental areas. Market to individuals and businesses the advantages of living/locating in a smart growth development reduced costs and stress as a result of less commuting, reduced employee turnover and higher employee motivation for businesses under take research to quantify these benefits. Provide a variety of transportation choices and refocus federal transportation policy on public transit and away from highways. Make development decisions predictable, fair and cost effective communities may choose to provide incentives for smarter development and provide guidelines for the redevelopment of brown field sites. Encourage citizen and stakeholder participation in development decisions when people feel left out of important decisions they wont be there to help out when tough choices have to be made.

3. 4.

5.

6. 7.

8. 9.

10.

4.

How Is The Smart Growth Concept Being Made To Work In The U.S.? It is interesting to note that federal, state and local governments in the U.S., the self-professed home of laissez faire capitalism, are far less reluctant to utilise creative economic incentives as well as sophisticated marketing and demographic forecasting techniques and strong planning and legislative controls to push the smart growth message than we are in New Zealand and Australia.. For example, at the federal level the Community Reinvestment Act encourages lending institutions to invest in smarter development in the communities that they serve and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act requires financial institutions to tell the public how they are investing their funds. The Transportation Equity Act (known as TEA-21) promotes greater integration between transportation and land use planning, including promotion of alternatives to private vehicle based travel. Some federal politicians have recently been elected on Smart Growth platforms. The private sector is also playing its part with banks in Seattle, Chicago and California offering a Location Efficient Mortgage which recognises that people buying in transit rich neighbourhoods tend to own fewer motor vehicles and can apply those savings to finance mortgages that are $US 15,000 50,000 greater than they would otherwise qualify for. In Atlanta, once the U.S.As poster child for sprawl, Bell South - one of the regions largest employers - has announced that it will close 75 suburban offices and consolidate them in 3 new offices located at railway stations. At the local level, existing local government infrastructure investment is being redirected to Smart Growth Projects. In Austin Texas, for example, a Smart Growth Matrix score card is used to offer developers incentives for supporting smart growth. Under the scorecard projects are awarded points for positive attributes such as: public transit and pedestrian access: brown field redevelopment, whether or not infrastructure exists on site and good urban design. Projects that accumulate enough points can receive benefits from a waiver of consent fees to the provision of public funds for new infrastructure that they project sponsor would normally provide. For example, a new mixed used project in the Citys urban core with excellent urban design, pedestrian and public open space attributes has received a $U.S. 7.6 million subsidy.

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

At the state level, the Maryland Smart Growth and Neighbourhood Conservation Act requires that existing older communities be given priority for public infrastructure, services, schools and other neighbourhood improvements. Maryland also has a Live Near Your Work Program in which employers and state and local governments provide $US 3,000 to people who purchase homes near their workplace. A variety of other states have now enacted laws that embody this approach to growth. New Jerseys latest transportation law, for example, recommends that roadway and transit system maintenance reach acceptable standards before new highways are built. Californias Safe Routes to School Act will provide $20 million to communities to improve pedestrian infrastructure locally and reduce school trips by motor vehicle. Apart from the financial incentives, there is also a demographic imperative at work: 31% of U.S. households are childless single people and the number of empty nesters and old people that seek out walkable, liveable neighbourhoods with convenient public transport are a growing proportion of the population. This trend, at least, we share with the U.S. and increasingly residential marketing firms are undertaking demographic research to match housing type to the available market. 5. Is Smart Growth Achievable And What Are The Challenges Planners Face In Achieving The Vision? The Liverpool example in Sydney and the Flat Bush example in Auckland show how the principles of smart growth can be applied to new urban growth nodes on the periphery of metropolitan areas. To the extent that they are greenfields projects, they do not follow the dictum of Smart Growth that existing communities and assets should be rebuilt and re-used first. However, both projects are set within regions where redevelopment of existing brownfield sites are also occurring as a matter of regional policy and are part of a regional growth strategy. While it is true that well designed, walkable, mixed use, energy efficient developments in the middle of nowhere may not qualify as smart growth, it does not seem like this is a valid criticism of these projects, at least conceptually. In both cases however, the challenges of implementation lie ahead. Broadly, speaking, the most major of these can be said to fall into the following categories: The challenge of regional co-ordination. The challenge of implementing good design on the ground. The challenge of providing a viable public transport alternative. The challenge of leading public opinion, gaining market acceptance and overcoming institutional inertia.

Regional Co-ordination From the authors perspective, it seems that this will be more of a challenge in Sydney than Auckland. NSW has 172 local government areas with 42 in the Sydney metropolitan area. While the Auckland Region admittedly is much smaller in population terms, it does have to only contend with four major city councils and 3 district councils when implementing a growth strategy. Additionally, Auckland has a strong statutory framework; the Auckland Regional Policy Statement, and the Regional Land Transport Strategy to underpin its regional growth strategy and provide strong statutory guidance to its key publicly owned infrastructure providers. At a local level this is reinforced by District Plans which must not be inconsistent with the Regional Policy Statement. This strong statutory basis is supplemented by non-statutory documents including the Regional Growth Strategy itself and the various sector agreements (North, South and West) where the local governments in these respective sectors of Auckland have committed themselves to achieving various targets for accommodating growth both within the existing urban area and within the greenfield areas identified within the Metropolitan Urban Limits set out in the Regional Policy Statement. The objectives are therefore clear and widely accepted. What is not so clear is exactly how to achieve them. However, this regional consensus is an important building block North American experience in implementing smart growth makes that very clear. In Sydney this strong statutory basis does not appear to be present. Planning NSW has set objectives for higher densities in documents such as that quoted earlier, yet the agencies who have to provide the supporting physical and social infrastructure do not appear to have made the same commitments to 4 SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

funding and timing. Good quality strategic planning at a local level also seems to be an issue. This is however probably easier to achieve at a sub regional level, such as in Auckland where the Territorial Local Authorities are fewer and larger and therefore less likely to be bogged down in parochial politics. Implementing Good Design Are we really equipped in the antipodes to produce the sophisticated urban design at the micro level to support higher density environments? In this sense, Sydney, as the more cosmopolitan and larger city, has the more developed tradition of higher density development, especially in the inner suburbs and middle ring suburbs along the well established rail routes. Yet Sydney too seems just as capable of producing unimaginative suburban landscapes on the urban fringe as Auckland. Recent commentary from the NSW Board of Architects on the creepy-crawly villas of the suburbs of Western Sydney, sound familiar to Aucklanders used to hearing similar commentary about Albany on Aucklands North Shore or Howick in South Auckland. However, many on both sides of the Tasman are recoiling as unfamiliar, super compact housing springs forth in our arcadian suburban landscapes. In principle, the development is in accord with popular public opinion which is broadly against suburban sprawl. Yet this same public opinion also appears to be against higher density housing, producing something of a conundrum for the planners. Given the poor design and quality of much of the higher density housing that has been built it is no wonder that the community reaction has not always been upbeat. A key issue in Sydney is the very distinct markets for housing between the inner/middle suburbs and outer suburbs (eg Liverpool). In the suburbs in which the Developing Sustainable Communities release areas are located, there are not many precedents for alternative forms of housing, and a continuing strong demand for the suburban castles. People in these suburbs are very resistant to anything they feel will impact on their property values, and they have a view that higher densities are slums. Who can blame them when the only real large scale higher density developments in those areas are the large 1970s Housing Commission suburbs with consist of hundreds of townhouses with their attendant massive social problems? For some of the new higher density developments the criticism is arguably misplaced, the design and detailing is unfamiliar but consistent with best architectural and urban design practice. But it needs to be acknowledged that design skills and experience for this type of housing is often an issue and the building industry is poorly structured and resourced to implement the detailed site planning strategies and marketing methods required to make higher density development work. It is axiomatic that as density increases so does the requirement for high quality design detailing and materials. We can readily identify some of the problems. Among them are primitively planned parking and turning areas, inadequately planned open space and lack of privacy and front door aspect often caused by excessively low budgets and poor planning of the housing units themselves. These and many other details suggest that some new developments will come to exemplify the worst in residential accommodation and certainly not qualify as smart growth. We need new forms of design protocols Amcord, Viccode and Res-code and the N.Z. derivatives are good examples which we are not afraid to enforce vigorously. We have to recognise that smart growth will not be guaranteed by density alone, real energy efficiency comes from site layout design, real durability of the building comes from good detailing and good materials. If basic good design rules are not followed smart growth will quickly come to be seen by the public as a very dumb option. Indeed, if higher density housing is to become widely accepted by the public it has to stay a step ahead of lower density alternatives by offering innovative additional features (e.g. greater energy efficiency, higher quality chattels and shared private recreational amenities) at each price point. Another key urban design issue is the need to provide a supportive urban context for higher residential densities. In some of our new medium density developments we have no supportive well designed pedestrian friendly road system, or linked communal (public) open space system which replaces the suburban backyard. There is often no local employment opportunities or social infrastructure of community, entertainment and retail facilities. To use an analogy that New Zealanders at least will be familiar with: these developments are like living in Coronation Street without the cobbled lanes, the Rovers Return or the clothing factory on Rosamond Street.

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

A Viable Public Transport Alternative Again, Sydney appears to be better prepared to accept Smart Growth than Auckland from this perspective. It is notable that a key plank in the Liverpool Sustainable Community project was the extension of the Liverpool Parramatta Transitway and the orientation of higher density development towards this feature. This consideration is not explicit at Flat Bush, presumably because planning for attractive (i.e. non-bus) passenger transport in this part of South Auckland is relatively embryonic and potentially decades away from being achieved, if ever. However, even in Sydney and particularly in the western suburbs, it seems essential public transport services currently lag behind development, or are very poorly provided (dependent on private bus companies which usually operate very few, and circuitous services, only during peak hours), thereby setting up the classic Catch 22 where, due to the lack of public transport infrastructure, development design is car-dominated resulting in densities at which public transport is uneconomic. As a result, the rate of increase in car usage is outstripping population increases. On both sides of the Tasman we need to ensure that adequate public transport is available very early in the development of a new area and that new areas must be planned around the provision of that transport. It was not always this way. Before the advent of the motorcar both Sydney and Auckland had very well developed public transit systems and the majority of all trips were made by tram or, as we would call it now, light rail. The tram system grew organically with the suburbs. While the commuters of inner city Sydney have not (out of necessity) forgotten how to use public transport those in Auckland, to a large degree, have and, as congestion catches up with them, they are having to make a painful readjustment. A key to achieving smart growth in new urban areas is lessening the need to commute by providing a greater range of local employment and recreational opportunities in mixed use development. We would be deluding ourselves, however, to think that people will not continue to find reasons to move about our metropolitan regions. As well as making provision for dedicated public transit corridors now (even if current and expected densities and preclude the actual construction of those transit ways) we need to find new and innovative ways of encouraging people to use public transit. While an exponential rise in petrol taxes may be the most effective method it is unlikely to be politically palatable. Carrots in the form of the kind of economic instruments used in the U.S.A. (referred to earlier) may be worth looking at. There is a need for a significant shift in focus towards the provision and funding of alternative forms of transport. In Sydney, there are significant issues with the funding of existing rail services (necessary maintenance and improvements) let alone the funding of extensions to rail lines and new services. In Auckland the Governments recently released transport package may go some way towards redressing the woeful public transport offerings, even with its heavy road emphasis. Leading Public Opinion and Overcoming Institutional Inertia A common issue in both jurisdictions is the degree to which it is possible to lead public opinion on the issue of achieving smart growth. As mentioned earlier, there is widespread agreement about the disadvantages of urban sprawl but less consensus on what methods should be used to tackle the problem. There is no doubt that planners need to employ marketing techniques to sell the smart growth message despite the offence the use of such techniques may cause to our neo-liberal sensibilities. What is needed is a sustained and well organised campaign not unlike those used to address the road safety and smoking issues. The Smart Growth America organization provides a possible model of a broad coalition of political, social, environmental and business agendas which can apply considerable resources to the task of public education. However, we may be overestimating the task. As the Flat Bush case study shows, many of the key attributes of smart growth are those which large sections of the community, when asked, will nominate as being attributes which they desire in their local environment. Similar themes emerge in Australia. A recent survey undertaken as part of the Sustainable Transport for Sustainable Cities project by Sydney Universitys Warren Centre for Advanced Engineering identified that:

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

Residents are deeply concerned about the future of Sydney and want to see stronger, long-term planning; Sydneys transport and traffic problems are serious; Traffic congestion is the most critical problem; Residents make a variety of personal tradeoffs between housing, transport and lifestyle. But there is broad consensus on the problems confronting Sydney and desirable directions for its future development; Both the public and decision-makers favour strategies to reduce traffic over building more freeways as the solution to traffic congestion. But the decision-makers underestimate public support for demand management; and There is a strong preference among residents for improving public transport even at the expense of the road budget. Decision-makers underestimate this support. There is no doubt that many in the community are opposed to current methods of implementing smart growth which they believe have not addressed local impacts such as loss of privacy and generation of traffic. However, there is general support for housing strategies involving well-planned medium and higher density development among the public. Perhaps the greater challenge facing planners in this area is that of institutional inertia. Many dominant residential development companies are unconvinced of the depth of the market for this type of housing in the outer suburbs and say that they will only consider alternative forms of housing if critical public transport and community infrastructure is in place first. Some of the major lending agencies in New Zealand are very conservative and regard with alarm the new medium density housing developments which challenge the conventional wisdom of the commodity driven housing marketplace. They cite the difficulties in finding suitable comparables for valuing new and innovative forms of housing asa stumbling block. The reality is that the very diversity that defines smart growth makes assessing institutional risk more difficult. Smart growth principles prescribe a customised and locally tailored approach to development while the mortgage market prefers standardised products. The financial institutions and instruments underlying land development isolate components of the built environment to lower perceived financial risk. The result is places which, like their financing, are narrowly focussed. We need to find inventive ways to adapt highly focussed financial instruments to innovative projects and to demonstrate that risk is lowered rather than increased by building more sustainable urban areas. It is in this area that governmental agencies can perhaps lead by exerting some influence over those lending policies. The demographic imperative can be used here decreasing household size and an aging population are facts that even the most stubborn housing developer or financial institution would find it hard to argue with. Again the issue is providing this information in an easily digestible form through more sophisticated marketing. The examples of economic instruments used in the USA quoted earlier are worth considering. There is no doubt that if we are serious about addressing the issue of sustainable development in our largest cities a whole of government approach including such unlikely allies as Treasury and the Reserve Bank is going to be needed. Summary To return to the questions that we posed earlier in this paper: Smart Growth is achievable but as well as developing great plans, there is a critical need to focus on the challenges associated with implementation. This requires commitment from all levels of government and all professions involved in the implementation process. Critical success factors include: Coordination and commitment a strong regional policy framework and a whole of government approach is essential; Improving design performance; Adequate funding funding of up front physical and social infrastructure (especially public transport) is critical; A more co-ordinated and sustained educational campaign is required not just targeted at ordinary citizens but at our lending institutions and residential development companies.

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

We face very similar challenges on both sides of the Tasman. We can learn a lot from each other but we can also learn from the Americans particularly in the area of the importance of selling the idea of smart growth to the community, service providers, institutions and the private sector and forming public and private partnerships to implement that idea. We can also learn from them in terms of moving beyond implementation by regulation to the use of a range of economic instruments. The challenge lies ahead. Can we find the tools to ensure that smart growth is a trend rather than merely trendy?

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

APPENDIX: CASE STUDIES

SmartGrowth.doc

____________________________________________________________________________

CASE STUDY 1: FLAT BUSH , MANUKAU CITY AUCKLAND.

OVERVIEW The Flat Bush area is the last significant "greenfields" area in Manukau City and provides a unique opportunity to plan for a new town from an early stage allowing for an integrated approach in promoting the sustainable development of the city. The area consists of approximately 1700 hectares of land in the southeastern part of Manukau City and is the largest "new town" identified in the Auckland Regional Growth Strategy. It is estimated that the population of 40,000 people will be reached in the next twenty years. The Flat Bush area is located immediately to the east of the existing urban development of Manukau City and is flanked on its eastern boundaries by a natural catchment boundary which is characterised by steep to moderate hills the high point rising some 300 metres above the main basin area. Approximately one half of the catchment has been identified and protected by Manukau City Council for future urban purposes since the early 1970's which has resulted in the retention of pastoral land uses with relatively little land fragmentation. The other half of the catchment has only been identified for urban purposes since the Flat Bush consultation process began almost 5 years ago and has therefore seen a considerable amount of fragmentation into "lifestyle" blocks in the previous 30 years. CONSULTATION In developing the growth concept for the Flat Bush area an extensive consultation process has been ongoing for the past four and a half years. This has culminated in the Council notifying Variation 13 Flat Bush in June 2001 East Tamaki Consultative Workshop June 1997

The consultative process kicked off with a three day Consultative Workshop with stakeholders held in June 1997. Over 400 invitations were sent directly to identified stakeholders including landowners and residents in the study area and government agencies. The advantages of holding a consultative workshop were seen as: involving a meaningful community input improved consensus of stakeholders achieving a better design outcome for urban development of the catchment achieving faster planning outcomes with less litigation. achieving financial savings and value gained for both the public and private sector.

During the workshop participants were broken into small groups of approximately ten people to explore what physical and social attributes their ideal community would consist of. Responses to the standard questions varied from group to group although there was a high degree of consistency. The following is a summary of the key components that were identified by most groups 1. What people like about places house variety and choice for all ages and cultures areas of multi use - vibrant alive places; shops, eating, residential, entertainment friendly people in the street not always having to use the car easy movement both personal and vehicular clean fresh air parks/green spaces uniqueness of areas security/safety somewhere to walk to eg cafe peace quiet and privacy trees

SmartGrowth.doc

10

____________________________________________________________________________

2.

sense of space

What dont you like about existing places? traffic congestion crime, graffiti high fences e.g. Botany Road uniformity and blandness of existing areas Big Box shopping malls travelling long distances lack of space and privacy large houses on small lots What social/cultural characteristic would your ideal community have? sense of community and belonging mixing of people and cultures of all ages a place of community focus - exchange ideas, meet people, a place of creativity and inspiration shared use of community facilities safe environment neighbourhood cohesion and identity What economic characteristics would your ideal community have? diversity in economic activity convenient access to employment in the local area heavy industry is undesirable choice of workplace - mixed with other activities in the community where there are no adverse effects good quality shopping areas and work environments What natural and physical attributes would your ideal community have? retain the natural drainage elements and native bush clean water and air natural topography should be retained no congestion convenient public transport underground services including high tension lines accessibility to places of entertainment, learning, day care, medical services including accessibility by alternatives means such as walking and cycling choice of housing types safety a sense of community/sense of place What will the ideal city be like in ten years time? protection of significant natural features reduced dependence on the car efficient public transport system including nodes of mixed use activities with supporting facilities opportunity to live, work and play in the same area unpolluted air, water, soil safe city sense of identity and pride in the community excellent public spaces and facilities diversity of culture housing choice for all cultures, ages, incomes cultural heart or focal point for the community

3.

4.

5.

6.

SmartGrowth.doc

11

____________________________________________________________________________

Through the workshop process the ten separate Concept Plans that were developed by the groups were synthesised by the design team and were reported back to the workshop for further comment. A draft Concept Plan was then developed and made available for public submissions, which culminated in the Development East Tamaki Concept Plan being adopted in September 1999. The Concept Plan identified a number of further detailed investigations to be undertaken including; a Catchment Management Plan, Town Centre Development Framework and further assessment of Transportation Issues. KEY ELEMENTS OF THE CONCEPT PLAN Key Objectives/Goals To achieve an urban form that respects and works in harmony with the natural environmental patterns that exist in the East Tamaki/Flat Bush area To promote the development of public values and recognition of the importance of the public realm in achieving healthy sustainable communities To reduce the reliance on the private motor car as a means of transportation To maximise accessibility for all ages and cultures, including accessibility to housing choice, mobility, employment To achieve a reduction in travel demand and increase choice of travel modes To facilitate the establishment of a strong central focus for community and civic life To facilitate the establishment of a community that can celebrate its diversity and maximise opportunities for innovation To facilitate an urban form that is flexible such that it can adapt to the constantly changing values and pressures which shape our natural and physical environment

Key Features of Adopted Concept Plan (Refer Figure 1) A new community containing up to 45,000 residents Protection and enhancement of the natural gully/stream areas and their integration into the urban fabric. A new Town Centre based around a traditional mainstreet concept. The location is on the eastern side of Barry Curtis Park which provides a unique opportunity to develop a focal point around which the Town Centre could develop. It is envisaged that this Town Centre would contain a diverse range of activities including residential, retail, office, community and light industrial activities. The Town Centre would be characterised by a compact pedestrian friendly environment. Three Neighbourhood Centres are proposed which will provide for a diverse range of activities. They are strategically located throughout the area on main roads where public transport options and accessibility will make them most viable. Neighbourhood centres are envisaged to be developed around the principle of being a pedestrian friendly mainstreet based environment. A range of residential housing types are envisaged including detached or semi detached dwellings, terrace housing, townhouses, and apartments. Overall the densities suggested are higher than those found in traditional suburban areas. This is necessary in order to utilise a finite land resource more efficiently in light of a rapidly growing population and to encourage an urban pattern that can support alternative forms of transport including walking, cycling, and public transport. Higher average densities will result in a better range of services being available locally such as, shops, health and welfare facilities, recreation facilities, and child care. Overall it is suggested that the following densities should be achieved:

SmartGrowth.doc

12

____________________________________________________________________________

2 Low Intensity Residential / Rural area 5,000m Medium Intensity Residential areas 15 dwellings per hectare (overall average) High Intensity Residential area 20 dwellings per hectare (overall average)

It is anticipated that residential densities would be highest closest to the Town Centre and Neighbourhood Centres. Connectivity and permeability of the street system should be maximised in order to promote convenience, social interaction, and to enhance user safety in the street and security of property. Buildings should positively address the street and other public spaces by providing good functional relationships to the public realm and providing opportunities for informal surveillance. Encourage along the main road corridors a wide range of activities including non-residential activities. These mixed use corridors will provide opportunities for residential, employment, local convenience shopping, activities such as medical centres, and will support public transport options.

FIGURE 1 - FLAT BUSH CONCPET PLAN

SmartGrowth.doc

13

____________________________________________________________________________

VARIATION NO 13 FLAT BUSH The Concept Plan in addition to the Catchment Management Plan and the Town Centre Development Framework have all assisted in the preparation of Variation 13 to Manukaus Proposed District Plan. Variation 13 was notified by the Council in June 2001 and proposes a comprehensive new section in the District Plan to provide for the management of growth in the Flat Bush area. Hearings on the submissions to the Variation were held in February and March this year, with decisions yet to be made by the Hearings Committee.

SmartGrowth.doc

14

____________________________________________________________________________

CASE STUDY 2 HOXTON PARK RELEASE CORRIDOR, LIVERPOOL CITY, SYDNEY

OVERVIEW The Developing Sustainable Communities (Stage One) project, undertaken by GHD for Liverpool City Council, forms one of the important steps in planning of three significant release areas (total area over 1,500 ha) located in the Liverpool Local Government Area. The areas, known as the Hoxton Park release corridor, include: Edmondson Park (the composite site); Prestons/Yurrunga; and Hoxton Park Aerodrome. The overall vision for the project is represented by the project title, which is to develop more sustainable communities in the new release areas. Liverpool City Council, together with other Local and State Government agencies, is working to ensure the development of the corridor will focus on: smart growth principles; and sustainable development. In pursuing the above, Liverpool City Council commissioned GHD to prepare an Urban Development Framework. The project focused on undertaking relevant investigations and setting in place guidelines to ensure the planning and development of sustainable communities, satisfying objectives according to four critical dimensions: transport and access; natural environment; built environment; and community. The outcome of the project is a strategic (or structure) plan - the Urban Development Framework. GHDs APPROACH

GHDs approach to the project involved the following: planning a community with greater access to an efficient network of public transport and non-motorised travel opportunities (such as walking and cycling);

SmartGrowth.doc

15

____________________________________________________________________________

developing an integrated computer based information system - an Environment Baseline System to provide an interactive information base; analysing the planning and policy context; providing for social and community planning needs; ensuring that awareness of market and development trends informed the project; analysing the urban form and urban design potential and needs, and producing a number of development scenarios; establishing infrastructure and services requirements; and determining potential traffic and transport implications. The study area called for an urban design/urban form concept that is distinctive, respects the intrinsic values of the environment and responds appropriately to the design and implementation requirements of a new form of higher density, sustainable development. Based on the studies undertaken during the project, three options (development scenarios) were considered and evaluated and a preferred urban form for the study area was recommended. An Urban Development Framework was prepared to represent the preferred urban form for the study area. THE ROLE OF INTEGRATED TRANSPORT PLANNING The transportation planning for this project was based on the following assumptions: If well-planned transit lines are established in the earliest stages of development, then they will seed transit oriented development. If established in the context of good urban design, transit oriented development is likely to assist in achieving the aims of sustainability and quality of life. If transportation and land use are successfully integrated, the aims of accessibility and more sustainable transportation will be achieved. This will be the natural result of residents and visitors free choice to exploit the transportation opportunities available to them. This link between context, choice and behaviour can already be seen in places throughout Sydney. The fundamentals of integrated transportation planning are fairly straightforward, and work at many levels: Transit links should be established along likely desire lines of future development. Trunk transit lines with high levels of service have a more beneficial effect on urban form, structure and design than dispersed routes i.e train for key centres, light rail (if possible) or otherwise busway for transit corridors. Land uses with highest levels of travel demand / generation should be established along transit lines. Urban structure should be focused on the transit lines. Applying these principles to a real situation, and balancing them with the many other issues that affect the evolution of a community, that poses the greatest challenge to urban planners. The key transportation elements of the Developing Sustainable Communities Project are: An extension of the planned transitway from Hoxton Park Road to the proposed Bardia town centre - This would link to the developing transitway network in Western Sydney (and the destinations it serves) and would provide a highly accessible mode within the Edmondson Park and Prestons Release areas. The proposed Edmondson Park Railway line This would provide a point of interchange between the CityRail and transitway network and reinforce Bardia as a key transit node. This would provide the necessary dynamic to seed a mixed use, high density town center in the Edmondson Park area. Reduce the attractiveness of travel by road - Traffic modelling for the project was based on the premise of travel demand management. In practical terms, this meant that improvements to the road network are only made after congestion levels have been reached. Not only does this reduce the potential to induce travel demand by road, but it delays the need to invest in expensive road works, and increases the relative attractiveness of transit. Integrate urban form and transportation promote non-motorised transport - This recognises that the success of transit-oriented development rests as much in the attention to urban design quality as it does in the transit infrastructure itself. This includes providing street layouts and alignments that promotes pedestrian and cyclist

SmartGrowth.doc

16

____________________________________________________________________________

accessibility, the efficient operation of local feeder bus services. Minimising the negative impacts of private vehicles in areas of highest people activity. THE URBAN DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK The project team suggested that the proposed development of the Hoxton Park Release Corridor should broadly involve: Edmondson Park - The focus will be on providing a balance between commercial and residential development. Higher density development will centre around a public transport node (the town centre, also known as Bardia) and on land that adjoins the possible extension to the Liverpool-Parramatta Transitway. More traditional densities for residential development will be applied for the balance of the land. Development should be encouraged around the centre at a density of up to 50 dwellings per ha. On the balance of the site, a minimum density of 15 dwellings per ha, with a minimum of 20 dwellings per ha on land along the possible extension of the Transitway. Development of the centre should involve a strong mixed use/commercial core/employment node. Prestons/Yurrunga - The focus will be on encouraging a mix of commercial and residential development. Employment areas will be located on land that can access and take advantage of the proposed extension to the Transitway and the Western Sydney Orbital. Residential uses are proposed for the remaining areas of the site, reflecting nearby residential uses. Development should be encouraged at a minimum density of 15 dwellings per ha, except in mixed use areas along the Transitway, where a minimum density of 20 dwellings per ha will apply. Hoxton Park - The focus will be on encouraging a more traditional level of density for residential development. This area has minimal access to significant public transport links and provides an attractive area for lower density development. Development should be focussed on the southern sections of the site. A minimum density of 15 dwellings per ha will apply. HOW WAS THE PREFERRED FORM OF DEVELOPMENT REACHED? Three alternative development scenarios (options) were developed in the context of the desired urban form outlined above for consideration and testing. These were intended to represent three points along the spectrum of the wide range of possible options (broadly high, medium and low in terms of the level of market change proposed), with the spectrum varying according to intensity of development, and the provision of transit infrastructure. The main difference between the options was the intensity of development at Edmondson Park influenced by different options in the provision of transit. Summary of proposed options compared to the existing market Option Existing Market 1 2 3 Proportion low density 80-90% 30% 60% 93% Proportion med-high density 10-20% 70% 40% 7% Indicative population levels 68,000 53,000 48,000

The proposal to increase densities to the level discussed during the project (options 1 and 2) represents a significant change to the urban form and density currently being developed in Western Sydney. Based on the input of Council, comments received from representatives of the development industry, the objectives of the project, and likely infrastructure requirements of the different options, it is recommended that Option 2 (the middle density option) be the preferred scenario for further development and investigations. This involves approximately 40% of dwellings provided at medium to high densities (ie >20 dwellings per ha) which is a market shift from low density development of approximately one-third. This market shift was considered to

SmartGrowth.doc

17

____________________________________________________________________________

be achievable, being half as great as that which would be necessary to achieve the highest density form of development practicable (ie Option 1). The traffic/transport model developed calibrated during Stage One was used to determine the implications of the three options. Recommendations in terms of infrastructure needs (transport, water, sewage etc) associated with the preferred option, and the staging of development, were also established. PROJECT OUTPUTS Urban Development Framework and Supporting Reports To accompany the Urban Development Framework, the GHD project team produced the following outputs: Part A - Project Summary This document provides a summary of the overall project, including objectives, approach, context, planning requirements and key outcomes. Part B - Background Reports The background reports provide a summary of the outcomes of investigations undertaken as part of the project. Detailed reports are provided in relation to the following key components: Transport planning Urban form and development scenarios Infrastructure services and staging Social and community planning Development of the Environment Baseline System (project GIS) and supporting Excel spreadsheets Part C - Urban Design Guidelines The purpose of the Urban Design Guidelines is to recommend design principles and strategies to implement the preferred urban form and guide the masterplanning process. Smart Growth Plan The final step in the process was converting the outcomes of the GHD project teams work (the Urban Development Framework) to the Smart Growth Plan (ie the presentation step) by the Council project team. The aim of this step was to assist in wide communication of the outcomes, through the use of artists impressions, diagrams, simplified maps and guiding principles. The urban development framework provides the technical basis for the Smart Growth Plan.

SmartGrowth.doc

18

____________________________________________________________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY Greetings From Smart Growth America - Donald Chen (2000) The Science of Smart Growth Donald Chen Scientific American December 2000 Shaping our Cities NSW Department of Urban Affairs and Planning (1998) Better design, layout vital for high-density housing David Turner- NZ Herald June 2001 Urban Area Intensification-Regional Practice and Resource Guide 2000Auckland Regional Council What Does Smart Growth Really Mean? Anthony Downs - Planning April 2001 Smart Growth - Potential Applications to Planning and Development In Australia Amanda Raleigh and Tom Pinzone - 2001

SmartGrowth.doc

19

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Pump Affinity Laws GuideDokumen3 halamanPump Affinity Laws Guidesubramanyanvenkat6185Belum ada peringkat

- IRC SP 118-2018 Manual For Planning and Development of Urban Roads and StreetsDokumen88 halamanIRC SP 118-2018 Manual For Planning and Development of Urban Roads and StreetsjitendraBelum ada peringkat

- EarthingDokumen40 halamanEarthingmamoun_hammad7917Belum ada peringkat

- Heat Exchanger VibrationDokumen3 halamanHeat Exchanger VibrationTim KuBelum ada peringkat

- Biomass To Ethanol ProcessDokumen132 halamanBiomass To Ethanol ProcessLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- VOL 1.1-Engineering Design Report For Roadway and Station-Final2 PDFDokumen180 halamanVOL 1.1-Engineering Design Report For Roadway and Station-Final2 PDFHüseyin Aytug100% (1)

- Ahmedabad Integrated Mobility Plan 2031Dokumen86 halamanAhmedabad Integrated Mobility Plan 203116gami100% (1)

- Bridges - Asia-22-25 02 10Dokumen84 halamanBridges - Asia-22-25 02 10LTE002100% (1)

- Traffic rules and regulations literature reviewDokumen13 halamanTraffic rules and regulations literature reviewMichael QuezonBelum ada peringkat

- Centrifugal PumpDokumen42 halamanCentrifugal Pumprumabiswas853100% (2)

- Bus BarsDokumen148 halamanBus Barsmimran18Belum ada peringkat

- Bhubaneswar E-Mobility PlanDokumen32 halamanBhubaneswar E-Mobility PlanICT WalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Andhra Pradesh Transit Orientied Development Policy 2022Dokumen51 halamanThe Andhra Pradesh Transit Orientied Development Policy 2022Raghu100% (1)

- Miami Dade Transit Route MapDokumen1 halamanMiami Dade Transit Route MapdamienleeBelum ada peringkat

- 2016 Smart City PresentationDokumen22 halaman2016 Smart City PresentationDeshGujarat80% (5)

- Ettv - BcaDokumen56 halamanEttv - BcaHo Chee YongBelum ada peringkat

- ZH - 09 Steel ConnectionDokumen65 halamanZH - 09 Steel ConnectionLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- YYJ - Stiff - 2003 Caternary Action - Steel BeamDokumen29 halamanYYJ - Stiff - 2003 Caternary Action - Steel BeamLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Bio Gas Burner 1Dokumen21 halamanBio Gas Burner 1saadullah_siddiqui6076Belum ada peringkat

- Oxygen RequirementsDokumen22 halamanOxygen RequirementsLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- ZH - 2005 RCDokumen99 halamanZH - 2005 RCLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Gas ChromatographDokumen21 halamanGas ChromatographLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- ZH - 09 Steel ConnectionDokumen65 halamanZH - 09 Steel ConnectionLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- YZ - 10 Intumescent CoatingDokumen26 halamanYZ - 10 Intumescent CoatingLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- YZ - 11 Intumescent Coating ModellingDokumen39 halamanYZ - 11 Intumescent Coating ModellingLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Building Digest 20Dokumen4 halamanBuilding Digest 20LTE002Belum ada peringkat

- PH MeasurementsDokumen12 halamanPH MeasurementsLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Soil WashingDokumen19 halamanSoil WashingLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Fire Sprinklers PDFDokumen28 halamanFire Sprinklers PDFChristopher BrownBelum ada peringkat

- Otis About ElevatorsDokumen14 halamanOtis About ElevatorsRajeshkragarwalBelum ada peringkat

- MethaneDokumen24 halamanMethaneLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- High PerformanceDokumen3 halamanHigh PerformanceLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Cal Methodology - Energy Saving - Electrical - HouseholdDokumen15 halamanCal Methodology - Energy Saving - Electrical - HouseholdLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Trigger Sprayer Dynamic Systems ModelDokumen5 halamanTrigger Sprayer Dynamic Systems ModelLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- 32438Dokumen154 halaman32438vasakaBelum ada peringkat

- I. Introduction, Purpose, and Study LayoutDokumen17 halamanI. Introduction, Purpose, and Study LayoutLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- 833 Anaerobic Digestion ParametersDokumen4 halaman833 Anaerobic Digestion ParametersLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Simulation of High-Speed FillingDokumen13 halamanSimulation of High-Speed FillingLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Toxicity of BiodieselDokumen53 halamanToxicity of BiodieselLTE002Belum ada peringkat

- Traffic Optimization in The Twin Cities of Hyderabad and SecunderabadDokumen31 halamanTraffic Optimization in The Twin Cities of Hyderabad and SecunderabadPrashanth DhudhelaBelum ada peringkat

- Capital City Ulaanbaatar Mongolia: Urban Transport Development PlanDokumen23 halamanCapital City Ulaanbaatar Mongolia: Urban Transport Development PlanVoli BeerBelum ada peringkat

- METRO1Dokumen12 halamanMETRO1Bhagyashri KulkarniBelum ada peringkat

- Sustainable Mobility Landscape in India - Internship Report, Joy ChatterjeeDokumen26 halamanSustainable Mobility Landscape in India - Internship Report, Joy ChatterjeeJoy ChatterjeeBelum ada peringkat

- Multi Modal Transit Hub As A Solution For Growing Urban Traffic Congestion in Mega CitiesDokumen9 halamanMulti Modal Transit Hub As A Solution For Growing Urban Traffic Congestion in Mega CitiesPrasoon MishraBelum ada peringkat

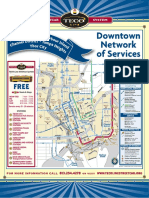

- Istrict Tampa Ybor City: Nnel D Ntown Tampa HarbouDokumen3 halamanIstrict Tampa Ybor City: Nnel D Ntown Tampa HarbougorditoBelum ada peringkat

- Route 590/594 Seattle-Tacoma ExpressDokumen3 halamanRoute 590/594 Seattle-Tacoma ExpressSam JoyBelum ada peringkat

- DIWA in BRT Systems 2013Dokumen3 halamanDIWA in BRT Systems 2013吳坤益Belum ada peringkat

- Transportation Economics: (Questionnaire) IdentificationDokumen81 halamanTransportation Economics: (Questionnaire) IdentificationJohn Paul GutierrezBelum ada peringkat

- Futuristic Studies On GSRTC Bus-Stand in Ahmedabad City: January 2018Dokumen5 halamanFuturistic Studies On GSRTC Bus-Stand in Ahmedabad City: January 2018HarshBelum ada peringkat

- JNN College Seminar on Design and Advantages of Bus BaysDokumen13 halamanJNN College Seminar on Design and Advantages of Bus BaysChandan CbaBelum ada peringkat

- YUTRA Summary PDFDokumen109 halamanYUTRA Summary PDFကိုနေဝင်း100% (3)

- Sustainable Urban Transport: Four Innovative Directions: Todd Goldman, Roger GorhamDokumen13 halamanSustainable Urban Transport: Four Innovative Directions: Todd Goldman, Roger Gorhamsiti_aminah_25Belum ada peringkat

- Janmarg Ahmedabad BRT System Date: February-2015 Route Name:-Ghuma Gam - Maninagar Bus Schedule Janmarg Station:Ghuma GamDokumen1 halamanJanmarg Ahmedabad BRT System Date: February-2015 Route Name:-Ghuma Gam - Maninagar Bus Schedule Janmarg Station:Ghuma GamKamleshVasavaBelum ada peringkat

- Document 1Dokumen2 halamanDocument 1Kathryn Paglinawan VillanuevaBelum ada peringkat

- Thakkarbapa Nagar GRP 2 17.11.2014Dokumen53 halamanThakkarbapa Nagar GRP 2 17.11.2014Giby AbrahamBelum ada peringkat

- Vermont Ave Bus Rapid Transit Technical Study PresentationDokumen27 halamanVermont Ave Bus Rapid Transit Technical Study PresentationMetro Los AngelesBelum ada peringkat

- EIA for Proposed BRTS in Pimpri-Chinchwad, MaharashtraDokumen168 halamanEIA for Proposed BRTS in Pimpri-Chinchwad, MaharashtraMuthu Praveen SarwanBelum ada peringkat

- CE 142 Case Study 1Dokumen7 halamanCE 142 Case Study 1MikaBelum ada peringkat

- Transportation Research Part F: Suresh Jain, Preeti Aggarwal, Prashant Kumar, Shaleen Singhal, Prateek SharmaDokumen11 halamanTransportation Research Part F: Suresh Jain, Preeti Aggarwal, Prashant Kumar, Shaleen Singhal, Prateek SharmaEka Octavian PranataBelum ada peringkat