Talent Id

Diunggah oleh

jaimelamboyDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Talent Id

Diunggah oleh

jaimelamboyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

LONG-TERM ATHLETE DEVELOPMENT: SYSTEMATIC TALENT IDENTIFICATION Darlene A. Kluka, Ph. D.

, Director, International Academy for Womens LeadershipGlobal Center for Social Change and Full Professor, Department of Health, Physical Education and Sport Science, Kennesaw State University; Founding member, USA Volleyball Sports Medicine and Performance Commission

There is no doubt that those associated with sport continue the quest for performance excellence. Coaches and athletes, in particular, continuously search for answers to the following questions: (1) What makes a champion athlete? What factors in talent identification can be used to predict performance success? (2) What is the role of performance-based, long-term athlete development and assessment? And (3) What is the role of sport science and technology in the development of skilled and empowered coaches who are responsible for creating environments conducive to performance excellence? Today we will focus on the set of questions involving talent identification. There seem to be three general categories of talent identification systems: Systematic, governmental systems; systematic, non-governmental systems; and nonsystematic approaches. Systematic, governmental systems former soviet bloc countries; China Systematic, non-governmental systems tennis, swimming w/ well-structured age-group programs; developmental infrastructure identifies and reinforces talent moving through system Non-systematic approaches somewhat random id systems w/no particular approach; physical education classes for scholastic teams by coaches Talent has several properties that are genetically transmitted and, therefore, innate. Nevertheless, talent is not always evident at an early age but trained people may be able to identify its existence by using certain markers. These early indications of talent may provide a basis for predicting those individuals who have a reasonable chance of succeeding at a later stage. Very few individuals are talented in any single domain; indeed, if all children were equally gifted, there would be no means of discriminating or explaining differential success. Furthermore, talent is specific to that particular domain. The complex nature of talent is highlighted by these principles. It is not surprising, that there is no consensus of opinion, nationally or internationally, regarding the theory and practice of talent identification. Usually professional clubs depend on the subjective assessment of their experienced scouts and coaches, employing a list of key criteria. These are set out as acronyms; for example, the key phrase incorporated in the scouting process of Ajax Amsterdam is TIPS, standing for technique, intelligence, personality and speed. Alternative lists include TABS (technique, attitude, balance, speed) and SUPS (speed, understanding, personality, skill). Talent detection refers to the discovery of potential performers who are currently not involved in the sport in question. Due to the popularity of soccer, for example, and the large number of children participating, the detection of players is not a major problem when compared with other sports.

Talent identification refers to the process of recognizing current participants with the potential to become elite players. It entails predicting performance over various periods of time by measuring physical, physiological, psychological and sociological attributes as well as technical abilities either alone or in combination (Regnier et al., 1993). A key question is whether the individual has the potential to benefit from a systematic program of support and training. Talent identification has been viewed as part of talent development in which identification may occur at various stages within the process. Talent development implies that players are provided with a suitable learning environment so that they have the opportunity to realize their potential. The area of talent development has received considerable interest of late, leading several researchers to suggest that there has been a shift in emphasis from talent detection and identification to talent guidance and development (Durand-Bush and Salmela, 2001). Talent selection involves the ongoing process of identifying players at various stages that demonstrates prerequisite levels of performance for inclusion in a given squad or team. Selection involves choosing the most appropriate individual or group of individuals to carry out the task within a specific context (Borms, 1996). For many years, scientists have attempted to identify key predictors of talent in various sports (for a review, see Regnier et al., 1993). In this type of research, particularly evident in Australia, China, Cuba, and the former Eastern bloc countries, there are attempts to identify characteristics that differentiate skilled from less skilled performers and to determine the role of heredity and environment in the development of expertise. For instance, identifying and selecting talented volleyball athletes are not straightforward operations. Detection and identification of talent are more difficult in team games than in individual sports such as running, cycling or rowing, where predictors of performance are more easily scientifically prescribed (see Reilly et al., 1990). Long-term success in a team sport is dependent on a host of personal and circumstantial factors, not the least of which is the coherence of the team as a whole and the availability of good coaching. These factors make it difficult to predict ultimate performance potential in many sports at an early age with a high degree of probability. Eastern European systems relied on the generation of a comprehensive database of personal and performance variables and formal monitoring of progress and development. The systems were most effective where clear relationships between individual characteristics were established. These were almost exclusively individual rather than team-based sports. The most systematic model was probably the one in the former Deutsche Democratic Republic (DDR). A fundamental pillar of the countrys tremendous international success in the area of elite sport involved a talent search program. Recently, in preparation for the 2000 Summer Olympics, Australia adopted some elements of the DDR talent identification approach by implementing a talent search program. In contrast, the West German system of elite sport never developed a systematic approach. Even after the German reunification of 1990, elements of a successful system were not seriously considered as appropriate measures of talent identification in a democratic society (Pfutzner, et al., 2001). Within the systems employed in the DDR, not every individual displaying characteristics of talent was selected for systematic training. Youngsters were selected for specialization, only on the provision that they were healthy and free of medical

anomalies; could tolerate high training loads; had a psychological capability for training; and maintained good academic achievement levels. More recently, the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) created a model for some European countries, most notably Great Britain, to follow. In preparation for the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, the AIS paid considerable attention to its own talent identification and development. A major effort was targeted at individual sports such as rowing, swimming, cycling and track. A novel approach to talent identification and development was adopted for womens soccer. The Australian system consisted of detecting individuals with athletic ability in field games and selecting them for a fast-track program of training in soccer skills. Specific to soccer in Australia, while individuals within the team achieved a limited success in the game, the Olympic Games experience did not yield convincing evidence that talent detection and identification was the perfect process in soccer. Matsudo (1987) described the pyramid model that was used in Brazil that embraced six tiers of performance abilities. The standards of proficiency ranged from physical education classes at the base of the pyramid to international competitors at its apex. Their test battery incorporated anthropometric, physiological and performance profiles. Its use in specific sports was limited, but phenomenal success was found in the sport of volleyball, with the direction of individuals at an early age to the sport to which participants seemed biologically most suited. What does this lead to? The most effective contribution from sport science to talent identification is likely to be multidisciplinary. Identifying talent for games at an early age is not likely to be mechanistic or unidisciplinary. Successful identification needs to be followed by selection onto a formal program for developing playing abilities and nurturing the individual towards realizing the potential already predicted. Eventual success is ultimately dependent upon a myriad of circumstantial factors, including opportunities to practice, staying free of injury, the type of mentoring and coaching available during the developmental years. Personal, social and cultural factors also influence ultimate performance. For example, most games played are possession sports. American football, soccer, baseball/softball, field hockey and basketball have roles and strategies that allow each team to control the ball for extended periods of time. One statistic kept for these sports is time of possession of the ball for each team. Using the sport of volleyball, it is a game of rebound and movement. The ball is never motionless from the moment it is served until it contacts the floor or is whistled dead by an official. The size of the court is relatively small for the number of players, creating a congested playing area. Because of this, the game has evolved into one of efficiency, accuracy and supportive movements. Each team has a maximum of three contacts with which to accomplish the games objective, which is to return the ball and have it contact the floor on the opponents side of the net within the boundaries of their court. The outcome of the rally, game and match becomes a summation of each players efforts. This is the ultimate in individual contribution and team effort. As a team sport, volleyball uses a net to create no intentional physical contact between opposing teams. Reaching over the net into the opponents court is permitted during the

follow through motion of the attackers arm after the ball has been hit, or in the act of blocking after the hitter has contacted the ball. The individual techniques of the game are quite different from those of most team sports. Because the essence of the game requires the body to move through all zones of movement, the ball can be played at the highest point of a jump or just inches from the floor. The forearm pass is one technique unique to the game. No other team sport fosters ball to forearm contact as an accurate and efficient skill. Sitting volleyball is yet another example of adaptations in volleyball performance technique. Developing Performance Excellence? Excellence in performance shares common roots regardless of its form of expression. The concert pianist, research neurologist, and Olympic athlete are all products of sequential, multi-stage development systems. The commonality among these pathways to excellence is surprisingly strong. In 1985, Bloom and colleagues conducted a study to understand how world-class talent is developed. They interviewed 120 people who had achieved world-class success in the fields of art, sport, music, and academics. Successful individuals had very similar learning and development stages. Bloom divided development phases into the early years, middle years, and late years. Balyi (2002; 2004), a sport scientist and coach from the Hungarian/Eastern European system, integrated much of what was involved in talent identification and long term athlete development in the Eastern European system and adapted it to meet the needs of democratic societies, with particular focus on UK Sport and Sport Canada. The quality of a talent identification system may influence the international success of a countrys elite sport in various ways. For example, a comparison of the results of Summer Olympic Games showed a decrease for Germany. Nation 1992 1996 2000 USA 13.6 % 13.3 % 11.1 % Russia 15.1 % 8.2 % 9.8 % China 6.8 % 6.3 % 7.2 % Australia 3.2 % 4.1 % 6.3 % Germany 10.6 % 7.4 % 5.4 % (Rtten & Ziemainz, 2004) At the same time, the German Olympic team was the oldest team at the last Olympic Games, and it was also the team with the lowest retention rate. In particular, a high retention rate has been emphasized as a major condition of further Olympic success. Mean Age Nation USA 27.3 years Russia 26.0 years China 23.4 years Australia 26.6 years Germany 27.5 years (Pftzner et al, 2001)

A high retention rate may be affected by both the quantity of potential talents available and the quality of the talent identification system. While the talent development in China can begin with approximately120 million youngsters in the age range of 10 to 14, the base in Australia is only 1.3 million. It can be stated that countries with lesser populations seem to be depending on very systematic approaches to talent identification. Australia, with the smallest population of the top 5 recently has implemented a systematic Talent Search Program, which already has shown several achievements at national and international championships. Retention Rate Nation China 50 % USA 72 % Russia 40 % Australia 65.8 % Germany 18 % (Rtten & Ziemainz, 2004) While the talent development in China can begin with approximately 120 million youngsters in the age range of 10-14 years, the base in Australia is only 1.3 million. It might be said, then, that countries with smaller populations seem to depend more heavily on a very systematic approach to talent identification. Australia, with the smallest population of the top 5 has recently implemented a systematic Talent Search Program which has already shown achievements at national and international championships. Nation 10-14 15-19 total talent pool USA 20 M 20 M 40 M 4.00 M Russia 13 M 15 M 28 M 2.80 M China 120 M 99 M 219 M 21.90 M Australia 1.3 M 1.3 M 2.6 M 0.26 M Germany 4.6 M 4.6 M 9.2 M 0.92 M (Rtten & Ziemainz, 2004)

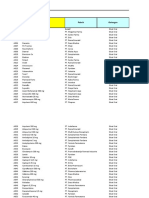

Talent identification system model: Talent Search - Australia

Talent ID Coordinator chooses athletes for Phase 2 physical education teachers

Tests done in all 2000 Schools in school physical education

Phase 2 Sport-specific tests Leisure Sports Phase 3 Sport Development Program

A number of criteria that are necessary for effective talent id tests have been identified. Here is a quick overview, as compiled by Kearney (Talent identification and development: The foundation of Olympic success White paper presented by Sports Science and Technology Division, USOC, 1999) StabilityVariable being measured is stable or unchanging over time and is only minimally impacted by growth and development. Variable must have a very strong genetic component to it, and be independent of the experience and training of the athlete. Tunneling The variable is measurable at a young age, and effectively predicts the adult status on that characteristic. If height is a variable with strong tunneling, height of 7-8 year olds would be highly predictive. Height, however, is not a good example of tunneling because of the significant variation in rate of development across people. Early maturers are taller, younger, and do not reach the adult height of some later maturers. Performance relevance Variables used for talent id should be intuitively relevant to performance. Critical variables (Matsudo, Victor) include those that are underlying characteristics that are common among all individuals who achieve a high level of athletic success within a sport discipline, but are not necessarily capable of differentiating among elite level performers. An example might be oxygen uptake among elite 10,000 meter runners. All individuals

capable of running less than 30 minutes for a 10 K will have an oxygen uptake above 75 ml.kg.min; however, there is a weak relationship between oxygen uptake of these elite runners and performance times. In contrast, a related variable is a variable that may help differentiate among elite level performers when present in concert with critical variables. Using the same example of 10 K runners, the velocity at lactate threshold, or velocity at vo2 max, has a much stronger relationship to competitive performance capacity than simply oxygen uptake. Assessment integrity Traditional measurement and evaluation criteria of validity, reliability and objectivity. In the area of talent identification, this can be challenging, as tests may be valid and reliable but not objective or any other combination. A test may validly assess a certain physiological, psychological or morphological characteristic, but that characteristic may not be a valid predictor of athletic talent. Test validity measures the intended variable, but that variable is not a valid predictor of talent; therefore, the test is not valid for use in talent identification. Applicability Needs to be applicable to the environment in which it is going to be used. The characteristics that contribute to the applicability of a test is that it must be simple, easy to administer, and field-based. There is a continuing debate about the use of field-based vs. laboratory-based tests. The general philosophy reflected in the literature is that fieldbased tests should be used for initial screening and that the results of these may be further differentiated by the use of laboratory-based procedures on a more select group of individuals.

Categories of Talent identification tests (Borms, 1996; Carter, 1985; Kearney, 2002) Morphological Somatotype (stature) Mass Height Fat-free mass Length and interrelationships among segment lengths Motor (Balyi & Hamilton, 2003) Strength Speed Reaction time Agility Flexibility Balance static and dynamic

Psychological and Sociological (Kluka, 2003; Calder, 2000; Reilly, 2003) Personality Traits Psychological profiling Readiness Coachability Self-concept Sociometric assessments Significant others Visual perception assessments Includes decision making and game Intelligence

If a talent identification test is 100 % effective, there would be a strong, linear relationship between results on the test and results in performance. This chart below graphically represents how the results on assessment and performance in competition might be distributed. The narrower the geometric distribution of the performance on the tests and the performance in competition, the more effective the talent identification test is. The false negative quadrant represents those individuals who score poorly on the test, but are able to do well in a competitive situation. The results of the talent identification test would be indicating they did not have the potential for success, but they achieved success. The false positive quadrant of individuals do well on the test, but do not achieve competitive results. There are a number of factors that have an impact on this test efficacy graph. First, there are very few situations where results on a single variable can effectively predict competitive performance. Consider the traits or characteristics that are essential for success for a woman softball athlete. It is obvious that an evaluation on any single variable will not provide a strong prediction of potential success. The typical application of an efficacy graph, then, is based on the results of a test battery or assessment on a series of variables.

C O M P E T I T I O N R E S U L T S

Talent Identification Tests

Best Mean TR

False Negatives

Mean CR False Positives

Poorest

(Kearney, 1999)

Test Results

Best

1. Most youth participate in sport in concert with either their parents or their direct peer group. It is very difficult to direct a young persons participation toward a sport that is not part of their social culture regardless of how they may have scored on a talent id test. 2. Political examples of former Eastern bloc countries potentially gifted athlete had an opportunity to significantly enhance the overall well being of their family, as well as be psychologically rewarded with the notion that they were contributing to a national goal. These factors increased motivation for young, potentially talented individuals, to participate in that activity. 3. Not only are traits genetically inherited, but there also appears to be a genetically-based trainability such that some individuals have the capacity to adapt positively to training, whereas other individual may not respond as favorably. Individuals who also have a broader range of genetic input may in fact have a greater potential for achieving high levels of performance in certain areas. 4. There may be a number of other intervening variables such as parental influence, peer group contribution, political priorities, and nutritional status

that can contribute to the evolution of an athlete from identification to long term performance success. In summary, the following points can be highlighted from our previous discussion: Talent detection, identification, and selection are only part of long term athlete development Talent identification models have been identified Nature and nurture interact to increase multidimensionality of an athletes long term performance success A multidisciplinary scientific approach to providing support system for coaches appears to be the most productive in helping gifted athletes realize their aspirations and potential.

What about the future? The following include possibilities for the attainment of appropriate long-term athlete development programs that include talent identification as a part of the equation for athlete success: National Governing Body (NGB) funding each national sport body in the U. S. would benefit by investing resources just below national competitive phase to identify and recruit talented and motivated athletes Those NGBs with limited funding - implement talent identification programs to increase probability that specific athletes will have success at highest levels Global talent identification summit including coaches, athletes, program directors and sport scientists to share knowledge of most successful international and domestic talent identification programs and development of meaningful assessments Analysis of talent identification systems on 3 quality dimensions that include structure, process and outcome as they relate to talent identification, talent selection, and talent development Suggested resources for additional information on this topic: Brown, J. (2001). Sports talent: How to identify and develop outstanding athletes. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Kluka, D. (1999). Motor Behavior: From learning to performance. Greeley, CO: Morton Publishing. Reeser, J. & Bahr, R. (Eds.). Handbook of sports medicine and science: Volleyball. Blackwell Sciences, Ltd. Starkes, J. L., & Ericsson, K. A. (2003). Expert performance in sports: Advances in research in sport expertise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Vickers, J. (2003). Decision training: A new approach to coaching. Calgary: CABC.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5795)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- BottomDokumen4 halamanBottomGregor SamsaBelum ada peringkat

- Theories of Learning and Learning MetaphorsDokumen4 halamanTheories of Learning and Learning MetaphorsTrisha Mei Nagal50% (2)

- Critical Care Nursing Assessment Form: R R R R R R R RDokumen2 halamanCritical Care Nursing Assessment Form: R R R R R R R RPipit Permata100% (1)

- CHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMDokumen19 halamanCHAPTER 8 f4 KSSMEtty Saad0% (1)

- Water TreatmentDokumen13 halamanWater TreatmentBayuBelum ada peringkat

- Bartos P. J., Glassfibre Reinforced Concrete - Principles, Production, Properties and Applications, 2017Dokumen209 halamanBartos P. J., Glassfibre Reinforced Concrete - Principles, Production, Properties and Applications, 2017Esmerald100% (3)

- NCP Ineffective Breathing ActualDokumen3 halamanNCP Ineffective Breathing ActualArian May Marcos100% (1)

- The Mental MeltdownDokumen5 halamanThe Mental Meltdownapi-460020991Belum ada peringkat

- Data Obat VMedisDokumen53 halamanData Obat VMedismica faradillaBelum ada peringkat

- InotroposDokumen4 halamanInotroposjuan camiloBelum ada peringkat

- Musa Paradisiaca L. and Musa Sapientum L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological ReviewDokumen8 halamanMusa Paradisiaca L. and Musa Sapientum L.: A Phytochemical and Pharmacological ReviewDeviBelum ada peringkat

- 48V 100ah LiFePO4 Battery Spec With CommunicationDokumen6 halaman48V 100ah LiFePO4 Battery Spec With CommunicationsoulmuhBelum ada peringkat

- Plyometric Training: Sports Med 2Dokumen9 halamanPlyometric Training: Sports Med 2Viren ManiyarBelum ada peringkat

- Presentation On "Insurance Sector": Submitted By: Faraz Shaikh Roll No: 9 Mba MarketingDokumen16 halamanPresentation On "Insurance Sector": Submitted By: Faraz Shaikh Roll No: 9 Mba MarketingFakhruddin DholkawalaBelum ada peringkat

- Practice Test For Exam 3 Name: Miguel Vivas Score: - /10Dokumen2 halamanPractice Test For Exam 3 Name: Miguel Vivas Score: - /10MIGUEL ANGELBelum ada peringkat

- Plastic Omnium 2015 RegistrationDokumen208 halamanPlastic Omnium 2015 Registrationgsravan_23Belum ada peringkat

- Leave of Absence Form (Rev. 02 072017)Dokumen1 halamanLeave of Absence Form (Rev. 02 072017)KIMBERLY BALISACANBelum ada peringkat

- Indirect Current Control of LCL Based Shunt Active Power FilterDokumen10 halamanIndirect Current Control of LCL Based Shunt Active Power FilterArsham5033Belum ada peringkat

- Distilled Witch Hazel AVF-SP DWH0003 - June13 - 0Dokumen1 halamanDistilled Witch Hazel AVF-SP DWH0003 - June13 - 0RnD Roi SuryaBelum ada peringkat

- 1 SMDokumen10 halaman1 SMAnindita GaluhBelum ada peringkat

- Content of An Investigational New Drug Application (IND)Dokumen13 halamanContent of An Investigational New Drug Application (IND)Prathamesh MaliBelum ada peringkat

- Starbucks Reconciliation Template & Instructions v20231 - tcm137-84960Dokumen3 halamanStarbucks Reconciliation Template & Instructions v20231 - tcm137-84960spaljeni1411Belum ada peringkat

- PMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Dokumen260 halamanPMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Santosh BasnetBelum ada peringkat

- Transformers ConnectionsDokumen6 halamanTransformers Connectionsgeorgel1980Belum ada peringkat

- RCMaDokumen18 halamanRCMaAnonymous ffje1rpaBelum ada peringkat

- Demolition/Removal Permit Application Form: Planning, Property and Development DepartmentDokumen3 halamanDemolition/Removal Permit Application Form: Planning, Property and Development DepartmentAl7amdlellahBelum ada peringkat

- Implementation of 5G - IoT Communication System 1 - RB - LAB EQUIPMENTDokumen32 halamanImplementation of 5G - IoT Communication System 1 - RB - LAB EQUIPMENTMaitrayee PragyaBelum ada peringkat

- FiltrationDokumen22 halamanFiltrationYeabsira WorkagegnehuBelum ada peringkat

- Ca 2013 39Dokumen40 halamanCa 2013 39singh1699Belum ada peringkat