Envi Socio and Socio of Natural Resources

Diunggah oleh

Sen CabahugHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Envi Socio and Socio of Natural Resources

Diunggah oleh

Sen CabahugHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Society and Natural Resources, 15:205 211, 2002 Copyright # 2002 Taylo r & Francis 0894-1920 /2002 $12.

00 + .00

Environmental Sociology and the Sociology of Natural Resources: Institutional Histories and Intellectual Legacies

FREDERICK H. BUTTEL

Department of Rural Sociology and Institute for Environmental Studies University of Wisconsin Madison Madison, Wisconsin, USA

W hile environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources nominally focus on the same subject matters, in practice the literatures in the two subdisciplines have tended to be quite separate intellectual enterprises. Environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources have different origins, their practitioners tend to have distinctive institutional locations, their problematics are different, and their theoretical tendencies differ considerably. I provide an overview of the divergent courses that have been taken within these two areas of inquiry, with stress on their institutional histories and intellectual legacies. Keywords environmental sociology, forests, natural resources, parks, rural, rural sociology, sociology of agriculture, theory

It remains relatively uncommon within contemporary sociological circles to devote serious consideration to the natural world and the social relations that shape and are shaped by the natural world (Murphy 1994; Dickens 1992; Benton 1989; Dunlap 1997). It is thus surprising that the minority of sociologists interested in societal-environmenta l relationships would be divided into two separate and largely harmoniously coexisting subdisciplines: environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources. While the notion that there is a systematic divide between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources has been apparent to me for a number of years, my inclination has always been to ignore this gulf and to see it as not particularly fundamental or consequential. Two personal experiences, however, have changed my mind about the signi cance of the environmental sociology =sociology of natural resources (ES=SNR) divide. First, shortly after my publishing a paper on theoretical issues and trends in ``environmental and resource sociology in 1996 (Buttel 1996), my colleague Don Field pointed out to me in a

Received 20 September 2000; accepted 5 July 2001. Presented at the International Symposium on Society and Resource Management, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA, June 2000. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the International Symposium on Society and Resource Management, Brisbane, Australia, July 1999. Address correspondence to Frederick H. Buttel, Department of Rural Sociology, 1450 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA. E-mail: fhbuttel@facstaff.wisc.edu

205

206

F. H. Buttel

convincing way that the underlying analysis and major recommendations were really only germane to environmental sociology and did not have much to say about the sociology of natural resources, which in his mind was a distinct eld of scholarship. Second, in my capacity as coeditor of Society & Natural Resources, which is regarded by a good many scholars as the international agship of the sociology of natural resources community, I am able to see more clearly from the pattern of submissions that there is a substantially different style of scholarship in this eld than there is in the environmental sociology eld with which I have been most closely associated. In this article I document the historical and contemporary nature of the ES=SNR divide. While acknowledging that the ES=SNR divide is not a serious problem and that there is a worthwhile complementarity between the two, I suggest that the existence of the divide suggests some unresolved issues of theory and method for the two communities of scholars interested in societal-environmenta l relationships.

Environmental Sociology and the Sociology of Natural Resources

The divide between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources has been a long-standing one, re ecting the relatively distinct origins of the two sub elds. The major contours of this divide are summarized in Table 1. While practitioners of both the sociology of natural resources and environmental sociology have made a good many claims that their elds have long and distinguished histories dating back even to the 19th and early 20th century classical sociologists it is most accurate to say that the sociology of natural resources is the more longstanding of the two subdisciplines, at least as a recognized subdiscipline and as an organizational entity in the United States. The sociology of natural resources was a relatively well established area of work by the mid-1960s. The sociology of natural resources eld at this time consisted of three very closely related groups of scholars. First, there was the growing cadre of social scientists (among whom sociologists were well represented) who were increasingly being employed by natural resource management agencies such as the U.S. Park Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Reclamation, Corps of Engineers, and so on. Second, there was a sizable community of scholars interested in outdoor recreation, many of whom would become active in editing and publishing in the Journal of L eisure Research and L eisure Sciences. Third, there was a signi cant group of rural sociologists interested in the sociology of resource-oriented rural communities and in rural natural resource issues; these rural sociologists, along with many resource agency social scientists and social scientists interested in outdoor recreation, joined groups such as the Natural Resources Research Group of the Rural Sociological Society. 1 The NRRG was quite active by 1965. Both intellectually and in practical or personal terms, these sociologists of natural resources were interested in matters pertaining to effective resource management, in more rational and socially responsive policymaking by resource agencies, in enhancing the cause of resource conservation, and, in the mid-1970s and after, in social impact assessment of natural resource development projects. Later, these sociologists of natural resources would expand their institutional networks to include the International Association for Impact Assessment and the International Symposia on Society and Resource Management in addition to the NRRG and the Journal of L eisure Research and L eisure Sciences. In addition, professional societies of resource biologists (e.g., the Society of American Foresters) would establish networks of ``social dimensions social scientists in which sociologists of natural resources would play very signi cant roles. Society & Natural Resources would shortly become the

Environmental Sociology and Sociology of Natural Resources

207

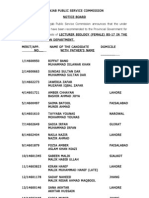

TABLE 1 Tendencies Within Environmental Sociology and the Sociology of Natural Resources Dimension Origins Environmental sociology Sociology of natural resources

Grew out of the Long-standing emphasis environmental movement among rural sociologists, leisure=outdoor recreation researchers, and social scientists in resource agencies Definition of ``Singular, encompassing, Local ecosystem or environment cumulative disruption landscape Main features Pollution, resource scarcity, Conservation, (local) carrying of the environment global environment, capacity stressed ecological footprints Definition of Reduction of aggregate Long-term sustained yields sustainability levels of pollution of natural resources, social and raw materials usage equity in allocation and use of resources, reduction of social conflict over natural resources Predominant cadre Liberal arts sociologists Natural resource agency staff; of practitioners college of agriculture=natural resources staff; rural sociologists Scale =unit of analysis Nation-state Community or region Metropolitan focus Nonmetropolitan focus Overarching Explaining environmental Improving public policy, problematic degradation minimizing environmental impacts and conflicts, improving resource management Theoretical Highly theoretical, Deemphasis on social theory commitments often metatheoretical

agship journal of the sociology of natural resources, though many sociologists of natural resources would publish the bulk of their work as agency bulletins or in the journals of the natural resource scientists. Most sociologists of natural resources today either are employed in a public or private resource management agency or, if they are employed as academics, are most likely to be found in resource departments (forestry, wildlife, range management, sheries, environmental studies) or related departments or programs (e.g., development studies or international agriculture programs) in colleges of natural resources, or in colleges of agriculture. Environmental sociology had quite different origins and institutional characteristics. Vocationally, most environmental sociologists have tended to be in conventional liberal arts sociology departments and to be scholars who were personally and professionally challenged by the rise of the environmental movement in

208

F. H. Buttel

the late 1960s and early 1970s. There have been three particularly important routes of recruitment into environmental sociology. A few of the scholars who would become well known in environmental sociology (e.g., William Burch, William Catton, Richard Gale) were active in the eld of the sociology of natural resources earlier in the 1960s, and extended their inquiry to include issues that were important within the emerging eld of environmental sociology. Most environmental sociologists, however, were relatively new converts to the eld, either as young or middlecareer professionals (e.g., Denton Morrison, Allan Schnaiberg), and especially as graduate students (e.g., Riley Dunlap); this new cohort of environmental sociologists was especially likely to have strong commitments to environmentalism , and to have elected to orient its scholarship to be relevant to environmentalism. Third, there were some environmental sociologists who had preexisting theoretical interests (e.g., William Catton in Durkheimian theory) who were stimulated to think differently about social theory as a result of the ferment of Earth Day and the mobilizations that followed. Environmental sociology largely emerged from whole cloth in the rst half of the 1970s (the signi cant contributions of Fred Cottrell and Walter Firey notwithstanding). In the very early days of environmental sociology the core issue was the nature and dynamics of environmentalism and the structure of the environmental movement. It is signi cant and striking that in the 1970s virtually all of the sociological attention paid to the environmental movement was by environmental sociologists, 2 rather than by sociologists of collective behavior and social movements, since the former saw this movement as being fundamental while the latter did not accord it this level of signi cance. Nonetheless, by the end of the 1970s the eld of environmental sociology would change very rapidly, and matters of theory if not metatheory would become particularly critical. The historical and institutional divergences between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources have led to some long-standing differences between the scholarship in the two elds. These differences are also summarized in Table 1. The sociology of natural resources tends to stress rural=nonmetropolitan topics, in large part as a re ection of the work its practitioners do for natural resource agencies and of the strong representation of rural sociologists and related rural social scientists (e.g., Machlis and Field 2000). Accordingly, the predominant conception of the environment from the vantage point of the sociology of natural resources is that of consumptive, preservationist, recreational, and related uses of primary resources (forests, sheries, mining, coastal zones, riparian zones, etc.). The sociology of natural resources retains a strong emphasis on management and policy, and thus tends to be relatively applied and empirical in orientation. The characteristic unit of analysis in the sociology of natural resources is that of the individual resource manager=user or the resource group or locality (particularly the nonmetropolitan community; see, for example, Lee et al. 1990). The sociology of natural resources literature also tends to be more eclectic in its pattern of citation, and often more multidisciplinary in its orientation. Environmental sociology, by contrast, tends to be more metropolitan in its stresses, in several respects. Environmental sociology is most preoccupied with manufacturing industry and with metropolitan-centere d consumption and metropolitan social groups. While primary resources are given some attention, this is basically a re ection of metropolitan-drive n demands by way of production and consumption institutions. The treatment of primary resources is also a highly aggregate one, with very little local detail, re ecting the industrial- and metropolitanoriented focus. Environmental sociologys conception of the environment is basically

Environmental Sociology and Sociology of Natural Resources

209

twofold: (1) pollution and (2) resource scarcity induced by metropolitan-drive n and industrially driven tendencies in production and consumption. Environmental sociology has tended not to develop a great deal of locally speci c empirical detail about the processes by which pollution and resource scarcity occur. Much environmental sociology, in fact, is not only largely theoretical, but even metatheoretical, in that it is rooted in debate about very broad and often relatively dif cult to test propositions. Environmental sociology has largely tended to have a national-societal unit of analysis, but increasingly environmental sociology has taken on a global or international level of analysis (Redclift and Benton 1994; Redclift 1996; Gould et al. 1996; Roberts and Grimes 1997). While the summary of the argument thus far as presented in Table 1 shows that the sociology of natural resources and environmental sociology exhibit a great many differences, perhaps the three most signi cant differences lie in the de nition of environment, the scale of research or unit of analysis, and the overarching problematic. As I have argued elsewhere (Buttel 2001), strategies for synthesis and crossfertilization will need to revolve around these three key dimensions of difference.

Discussion

In this article I have aimed to document the historical origins and current nature of the gulf between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources. It cannot be stressed too vigorously, though, that while there are clear differences in the origins of environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources and these continue to exhibit important intellectual legacies, the differences ought not to be exaggerated or to be thought of as intrinsic or desirable. It should also be noted that the divide is probably most evident in the United States, and is arguably not as pronounced elsewhere (e.g., in the United Kingdom). While U.S. exceptionalism in this regard should be reassuring in the sense that there is nothing intrinsic to the ES=SNR divide, it also suggests that there ought to be some readily available bases for synthesis and cross-fertilization. Second, there is a signi cant cadre of sociologists whose work has creatively straddled the divide between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources. Some names of this group of boundary spanners that come to mind are William Burch, William Freudenburg, Stephen Bunker, and Thomas Rudel. The prominence of this group suggests not only that synthesis and cross-fertilization are possible, but also that it can yield creative insights. Thus, while it will appear to some readers that I am exaggerating the differences that exist between the two subdisciplines, the fact remains that they re ect signi cant enduring divergences in styles of scholarship that have led the two subdisciplines to have less synthetic potential than could possibly be the case. In closing, it is also worth mentioning that there are two literatures that deserve special note in relation to the arguments made in this article. First, the sociology of agriculture literature which, incidentally, is seldom treated within the sociology of natural resources deserves notice on account of its advances in the areas of treating globalization phenomena, the biophysical character of resources and materials, commodity chains, and the role of environmental mobilization (see, for example, Bonanno and Constance 1997; Bonanno et al. 1994; McMichael 1994; 1996; Goodman et al. 1987). The sociology of agriculture literature has made particular gains in understanding the role of international organizations and regimes during the era of globalization at the end of the century (see Goodman and Watts 1997).

210

F. H. Buttel

Second, as suggested by Wilson (1999), the sociology of sheries has been the area of the sociology of natural resources that has been most comprehensive in grappling with the biophysical speci cities of the resource, the economic sociology of production, and the role of the science, the state, environmental movements, and globalization processes. The sociology of agriculture and sociology of sheries show that a number of the suggestions and recommendations in this article are realistic and have practical value. Finally, it is worth returning to a matter mentioned just in passing at the outset of the paper, concerning whether the ES=SNR gulf is itself a problem. A reasonable case can be made that there is a division of labor, and at least potentially a complementary relationship, between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources. There is little overt rivalry between the two approaches, and the weaknesses of one eld of scholarship are often areas of strength on the part of the other. While the complementarity interpretation is no doubt true to a degree, one might look at the matter in two other ways. Though I cannot make any precise empirical observations on the point, my guess would be that the rate of cross-citation between environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources is very low, so that what complementarity does potentially exist is not being very fully manifest in practice. The second point is that the two literatures not only have shortcomings, but they are shortcomings that take the form of mirror imaging. Thus, for example, environmental sociology has tended to err by having an overly general image of the state that states tend to be relatively centralized and to have de nite ``functions that affect environmental quality while the sociology of natural resources has tended to eschew theorizing the roles of states. Thus, the two literatures tend to err in ways that would become highly apparent if their practitioners were working more in concert and were grappling with differences in their assumptions and approach. My hope is that this article may suggest some points of departure for a more sustained dialogue than has been the case in the rst several decades of the surprisingly isolated coexistence of environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources. This closer dialogue will help scholars from both elds come to grips with their differences and learn through looking at these differences self-re ectively.

Notes

1. The role of rural sociologists in the sociology of natural resources is extensively discussed in Field and Burch (1988) , which is one of the most comprehensive book-length pieces in this eld. 2. Note, however, that over the past decade or so there has been a growing fascination with ``new social movements, among which environmental=ecology movements are prototypical within mainstream sociological circles (e.g., Beck 1992; Giddens 1994).

References

Beck, U. 1992. Risk society. London: Sage. Benton, T. 1989. Marxism and natural limits. New L eft Rev. 178:51 86. Bonanno, A., L. Busch, W. H. Friedland, L. Gouveia, and E. Mingione, eds. 1994. From Columbus to ConAgra. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. Bonanno, A., and D. Constance. 1997. Caught in the net. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Environmental Sociology and Sociology of Natural Resources

211

Buttel, F. H. 1996. Environmental and resource sociology: Theoretical issues and opportunities for synthesis. Rural Sociol. 61:56 76. Buttel, F. H. 2001. Environmental sociology and the sociology of natural resources: Strategies for synthesis and cross-fertilization. In Environment, society and natural resource management, eds. G. Lawrence, V. Higgins, and S. Lockie, 19 37. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Dickens, P. 1992. Society and nature. Hemel Hempsted: Harvester. Dunlap, R. E. 1997. The evolution of environmental sociology: a brief history and assessment of the American experience. In International handbook of environmental sociology, eds. M. Redclift and G. Woodgate, 21 39. London: Elgar. Field, D. R., and W. R. Burch, Jr. 1988. Rural sociology and the environment. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. Giddens, A. 1994. Beyond left and right. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. Goodman, D., B. Sorj, and J. Wilkinson. 1987. From farming to biotechnology. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Goodman, D., and M. Watts, eds. 1997. Globalising food. London: Routledge. Gould, K., A. Schnaiberg, and A. S. Weinberg. 1996. L ocal environmental struggles. New York: Cambridge University Press. Lee, R. G., D. R. Field, and W. R. Burch, Jr., eds. 1990. Community and forestry. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Machlis, G. E., and D. R. Field, eds. 2000. National parks and rural development. Washington, DC: Island Press. McMichael, P., ed. 1994. Global restructuring of agro-food systems. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. McMichael, P. 1996. Development and social change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. Murphy, R. 1994. Rationality and nature. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Redclift, M. 1996. W asted. London: Earthscan. Redclift, M., and T. Benton, eds. 1994. Social theory and the global environment. London: Routledge. Roberts, J. T., and P. E. Grimes. 1997. W orld-system theory and the environment: T oward a new synthesis. Paper presented at the ISA RC 24 Conference on Social Theory and the Environment, Woudschoten Conference Center, Geist, The Netherlands. Wilson, D. 1999. Fisheries sociology in the late 1990s. NRRG Newslett. spring/summer:6 8.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- EO 192 - Reorganizing The DENRDokumen26 halamanEO 192 - Reorganizing The DENRJoseph LazaBelum ada peringkat

- Systems Model of Human EcologyDokumen10 halamanSystems Model of Human EcologyCj Bantiling0% (1)

- Eo 247Dokumen31 halamanEo 247Xymon BassigBelum ada peringkat

- 5th National Report On Biological Biodiversity PDFDokumen157 halaman5th National Report On Biological Biodiversity PDFammend100% (2)

- Eo 247Dokumen10 halamanEo 247CLAIRE DENISSE DEVIS100% (1)

- San Francisco Nomination For SASAKAWA FinalDokumen16 halamanSan Francisco Nomination For SASAKAWA FinalVincent BautistaBelum ada peringkat

- Lca Mangatarem1 PDFDokumen58 halamanLca Mangatarem1 PDFBea 'Jane0% (1)

- Major Community ProblemDokumen8 halamanMajor Community ProblemRhegell CafirmaBelum ada peringkat

- How to Empower Children in the World: Earth Leaders for Environmental MonitoringDari EverandHow to Empower Children in the World: Earth Leaders for Environmental MonitoringBelum ada peringkat

- Forest Restoration and Rehabilitation in BangladeshDokumen45 halamanForest Restoration and Rehabilitation in Bangladeshreads1234Belum ada peringkat

- DMC 2013 06Dokumen18 halamanDMC 2013 06Donna RizaBelum ada peringkat

- Strengthening Local Disaster ManagementDokumen12 halamanStrengthening Local Disaster ManagementStratbase ADR InstituteBelum ada peringkat

- FLUP Checklist For Review and Outline GuideDokumen7 halamanFLUP Checklist For Review and Outline GuideSnoc Ko Nar UBelum ada peringkat

- Disaster Risk Reduction and ManagementDokumen29 halamanDisaster Risk Reduction and ManagementCyrus De LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Eo 263 - CBFMDokumen2 halamanEo 263 - CBFMAleen Baldemosa ArqueroBelum ada peringkat

- TechnicalBulletin2014-03FINAL PROGRAM and IMPACT Monitoring Guidelines For EcotourismDokumen24 halamanTechnicalBulletin2014-03FINAL PROGRAM and IMPACT Monitoring Guidelines For Ecotourismcphpl pambBelum ada peringkat

- NDRRMC MakadiyosDokumen14 halamanNDRRMC Makadiyosfrancheska ruizBelum ada peringkat

- International Climate Change Legal Frameworks: Climate Change, Coming Soon to A Court Near You—Report FourDari EverandInternational Climate Change Legal Frameworks: Climate Change, Coming Soon to A Court Near You—Report FourBelum ada peringkat

- Expanded NIPAS BillDokumen47 halamanExpanded NIPAS BillAnonymous OqgoU32iQBelum ada peringkat

- Ra 9275Dokumen21 halamanRa 9275theresagriggsBelum ada peringkat

- Good Practices in SWM - A Collection of LGU ExperiencesDokumen72 halamanGood Practices in SWM - A Collection of LGU Experiencesmalapatan menroBelum ada peringkat

- Disaster Risk Reduction Management AwarenessDokumen23 halamanDisaster Risk Reduction Management AwarenessPj ConcioBelum ada peringkat

- DAO 2016-12 Re PBSAP 2015-2028Dokumen240 halamanDAO 2016-12 Re PBSAP 2015-2028Aireen Villahermosa PiniliBelum ada peringkat

- Vol4 - 4-Yaptenco - FullPaper - A Paper On Open BurningDokumen14 halamanVol4 - 4-Yaptenco - FullPaper - A Paper On Open BurningJosmae MaskianolangBelum ada peringkat

- The Importance of The Rivers and Its MainDokumen7 halamanThe Importance of The Rivers and Its MainMichael WolfeBelum ada peringkat

- Priority Sites For Conservation in The Philippines:: Key Biodiversity AreasDokumen24 halamanPriority Sites For Conservation in The Philippines:: Key Biodiversity AreasSheila Laoagan-De VeraBelum ada peringkat

- Citizens Charter Attachment CDokumen95 halamanCitizens Charter Attachment CjohnpaulacostaBelum ada peringkat

- Lanuzaetal.2021.CarryingCapacityAssessmentofNature-basedEcotourisminMagsaysayParkandLogaritaSpringRiversideBilarBoholPhilippines-IntegraofCarcapandVA Sylvatrop v31n2Dokumen29 halamanLanuzaetal.2021.CarryingCapacityAssessmentofNature-basedEcotourisminMagsaysayParkandLogaritaSpringRiversideBilarBoholPhilippines-IntegraofCarcapandVA Sylvatrop v31n2airy orzagaBelum ada peringkat

- TB No. 2017-05 Guidelines For CM Habitat Assessment PDFDokumen39 halamanTB No. 2017-05 Guidelines For CM Habitat Assessment PDFEmerin DadeaBelum ada peringkat

- Indigenous Peoples HandoutDokumen3 halamanIndigenous Peoples HandoutMyka BarcenaBelum ada peringkat

- Pops Plan Workshops Assigned TopicsDokumen84 halamanPops Plan Workshops Assigned TopicsAngelito CortunaBelum ada peringkat

- CCA PLAN 2014 Magsaysay 2Dokumen37 halamanCCA PLAN 2014 Magsaysay 2LGU PadadaBelum ada peringkat

- Report 3 - WACSDokumen64 halamanReport 3 - WACSiking balonBelum ada peringkat

- Anti BurningDokumen11 halamanAnti Burningsiiickid musicBelum ada peringkat

- Natural ResourcesDokumen18 halamanNatural ResourcesTarun AroraBelum ada peringkat

- Dao 2010 16 - 200Dokumen46 halamanDao 2010 16 - 200Darwin MarianoBelum ada peringkat

- Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000: Geol. Jhoryl S. ImboDokumen23 halamanEcological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000: Geol. Jhoryl S. ImboclaireBelum ada peringkat

- Soriano Et Al 265 Journal Article For Critique PDFDokumen19 halamanSoriano Et Al 265 Journal Article For Critique PDFAbi KitmaBelum ada peringkat

- Letter Request For MRFDokumen1 halamanLetter Request For MRFrhaineBelum ada peringkat

- Coastal Resource Assessment GuideDokumen145 halamanCoastal Resource Assessment GuideArnoldAlarconBelum ada peringkat

- Proposed Ligawasan Marsh Protected Ara v1 PDFDokumen138 halamanProposed Ligawasan Marsh Protected Ara v1 PDFPochieBelum ada peringkat

- The Four C's Cycle ModelDokumen48 halamanThe Four C's Cycle Modelfpe_scribdBelum ada peringkat

- FMB ENGP - Forest Protection LogFrameDokumen24 halamanFMB ENGP - Forest Protection LogFramecholoBelum ada peringkat

- Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation (Drr-Cca) in The New Makati Comprehensive Land Use PlanDokumen30 halamanMainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation (Drr-Cca) in The New Makati Comprehensive Land Use PlanJCLLBelum ada peringkat

- Montabiong Open Dumpsite For The Municipality of Lagawe-PaperDokumen4 halamanMontabiong Open Dumpsite For The Municipality of Lagawe-PaperRevelyn Basatan LibiadoBelum ada peringkat

- Forestry Extension: Implications For Forest Protection: October 2009Dokumen8 halamanForestry Extension: Implications For Forest Protection: October 2009Sapkota DiwakarBelum ada peringkat

- 60th CMOG Anniversary BrochureDokumen12 halaman60th CMOG Anniversary Brochurearmynews100% (1)

- Biodiversity HotspotsDokumen11 halamanBiodiversity HotspotsChaitrali ChawareBelum ada peringkat

- IPRADokumen7 halamanIPRAJhane100% (1)

- LECTURE 2015 EMB LGU Overview Phil EIS System March 11Dokumen37 halamanLECTURE 2015 EMB LGU Overview Phil EIS System March 11Alexander Neil Cruz100% (2)

- Chapter 1 Module 1 I. Basic Concept in Tourism Planning and DevelopmentDokumen5 halamanChapter 1 Module 1 I. Basic Concept in Tourism Planning and DevelopmentRishina CabilloBelum ada peringkat

- National Mission FOR A Green IndiaDokumen44 halamanNational Mission FOR A Green IndiaNikki KellyBelum ada peringkat

- Puerto Princesa ECAN Resource Management PlanDokumen276 halamanPuerto Princesa ECAN Resource Management PlanLorenzo Raphael C. ErlanoBelum ada peringkat

- Muyong SystemDokumen8 halamanMuyong SystemlimuelBelum ada peringkat

- BIODIVERSITY StsDokumen6 halamanBIODIVERSITY StsDoneva Lyn MedinaBelum ada peringkat

- CHAPTER I Open BurningDokumen9 halamanCHAPTER I Open Burningjedric_14Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen8 halamanChapter 1Maria RuthBelum ada peringkat

- Group 1 Introduction To EIADokumen125 halamanGroup 1 Introduction To EIARhea Marie AlabatBelum ada peringkat

- Benefits of Wildlife ConservationDokumen29 halamanBenefits of Wildlife ConservationJayachandran KSBelum ada peringkat

- Which S of The Environment DoWe StudyDokumen11 halamanWhich S of The Environment DoWe StudyFelipe Ignacio Ubeira Osses100% (1)

- Gender Equality-The Case of The LGBTDokumen12 halamanGender Equality-The Case of The LGBTSen CabahugBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Law and Society ReviewDokumen164 halamanPhilippine Law and Society ReviewSen CabahugBelum ada peringkat

- In The Grand Manner: Looking Back, Thinking ForwardDokumen213 halamanIn The Grand Manner: Looking Back, Thinking ForwardAileen Estoquia100% (3)

- Article 15. Essential Requisites. - No Marriage Contract Shall Be Perfected Unless The Following Essential Requisites Are Complied WithDokumen20 halamanArticle 15. Essential Requisites. - No Marriage Contract Shall Be Perfected Unless The Following Essential Requisites Are Complied WithSen CabahugBelum ada peringkat

- Dda 2020Dokumen32 halamanDda 2020GetGuidanceBelum ada peringkat

- The Approach of Nigerian Courts To InterDokumen19 halamanThe Approach of Nigerian Courts To InterMak YabuBelum ada peringkat

- Estatement - 2022 05 19Dokumen3 halamanEstatement - 2022 05 19tanjaBelum ada peringkat

- CH 09Dokumen31 halamanCH 09Ammar YasserBelum ada peringkat

- rp200 Article Mbembe Society of Enmity PDFDokumen14 halamanrp200 Article Mbembe Society of Enmity PDFIdrilBelum ada peringkat

- Project ManagementDokumen37 halamanProject ManagementAlfakri WaleedBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine National Development Goals Vis-A-Vis The Theories and Concepts of Public Administration and Their Applications.Dokumen2 halamanPhilippine National Development Goals Vis-A-Vis The Theories and Concepts of Public Administration and Their Applications.Christian LeijBelum ada peringkat

- 01-Cost Engineering BasicsDokumen41 halaman01-Cost Engineering BasicsAmparo Grados100% (3)

- Trifles Summary and Analysis of Part IDokumen11 halamanTrifles Summary and Analysis of Part IJohn SmytheBelum ada peringkat

- Sarala Bastian ProfileDokumen2 halamanSarala Bastian ProfileVinoth KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Jive Is A Lively, and Uninhibited Variation of The Jitterbug. Many of Its Basic Patterns AreDokumen2 halamanJive Is A Lively, and Uninhibited Variation of The Jitterbug. Many of Its Basic Patterns Aretic apBelum ada peringkat

- API1 2019 Broken Object Level AuthorizationDokumen7 halamanAPI1 2019 Broken Object Level AuthorizationShamsher KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Ifm 8 & 9Dokumen2 halamanIfm 8 & 9Ranan AlaghaBelum ada peringkat

- Department of Mba Ba5031 - International Trade Finance Part ADokumen5 halamanDepartment of Mba Ba5031 - International Trade Finance Part AHarihara PuthiranBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Anglo-Saxon LiteratureDokumen20 halamanIntroduction To Anglo-Saxon LiteratureMariel EstrellaBelum ada peringkat

- Notes Chap 1 Introduction Central Problems of An EconomyDokumen2 halamanNotes Chap 1 Introduction Central Problems of An Economyapi-252136290100% (2)

- 14CFR, ICAO, EASA, PCAR, ATA Parts (Summary)Dokumen11 halaman14CFR, ICAO, EASA, PCAR, ATA Parts (Summary)therosefatherBelum ada peringkat

- Shop Decjuba White DressDokumen1 halamanShop Decjuba White DresslovelyBelum ada peringkat

- 10.4324 9781003172246 PreviewpdfDokumen76 halaman10.4324 9781003172246 Previewpdfnenelindelwa274Belum ada peringkat

- Final Seniority List of HM (High), I.s., 2013Dokumen18 halamanFinal Seniority List of HM (High), I.s., 2013aproditiBelum ada peringkat

- Dwnload Full Essentials of Testing and Assessment A Practical Guide For Counselors Social Workers and Psychologists 3rd Edition Neukrug Test Bank PDFDokumen36 halamanDwnload Full Essentials of Testing and Assessment A Practical Guide For Counselors Social Workers and Psychologists 3rd Edition Neukrug Test Bank PDFbiolysis.roomthyzp2y100% (9)

- CompTIA Network+Dokumen3 halamanCompTIA Network+homsom100% (1)

- Biology 31a2011 (Female)Dokumen6 halamanBiology 31a2011 (Female)Hira SikanderBelum ada peringkat

- Fatawa Aleemia Part 1Dokumen222 halamanFatawa Aleemia Part 1Tariq Mehmood TariqBelum ada peringkat

- Sop Draft Utas Final-2Dokumen4 halamanSop Draft Utas Final-2Himanshu Waster0% (1)

- Budo Hard Style WushuDokumen29 halamanBudo Hard Style Wushusabaraceifador0% (1)

- WFP AF Project Proposal The Gambia REV 04sept20 CleanDokumen184 halamanWFP AF Project Proposal The Gambia REV 04sept20 CleanMahima DixitBelum ada peringkat

- GDPR Whitepaper FormsDokumen13 halamanGDPR Whitepaper FormsRui Cruz100% (6)

- Basic Accounting Equation Exercises 2Dokumen2 halamanBasic Accounting Equation Exercises 2Ace Joseph TabaderoBelum ada peringkat

- Teens Intermediate 5 (4 - 6)Dokumen5 halamanTeens Intermediate 5 (4 - 6)UserMotMooBelum ada peringkat