TynBull 1970 21 06 Kidner DivineNamesInJonah

Diunggah oleh

Roberto GerenaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

TynBull 1970 21 06 Kidner DivineNamesInJonah

Diunggah oleh

Roberto GerenaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Tyndale Bulletin 21 (1970) 126-27.

THE DISTRIBUTION OF DIVINE NAMES IN JONAH

By F. D. KIDNER In this book of 48 verses no other divine terms beside Yahweh and Elohim are found, with the exception of El, which occurs once at 4:2 (in a quotation from Ex. 34:6). A simple count gives 25 occurrences of Yahweh and 15 of Elohim; but the latter divide into 8 examples in which Elohim is used absolutely, and 7 in which it is qualified by grammatical relation with a person or sphere, or with the name Yahweh. Apart from one instance (4:6), there is nothing unusual about the non-absolute occurrences of Elohim. Some refer to a god in the heathen sense (1:5, 6, 6), the rest to Yahweh as God of heaven (1:9) or as Jonah's God (2:1 (MT 2), 6 (MT 7)). In 4:6, however, there is a rarity, the composite name Yahweh Elohim, which is a feature of Genesis 2 and 3, out found elsewhere only 8 times in all. If some principles are discernible in these usages they could possibly throw a little light on the larger question of their distribution in the Pentateuch. Perhaps three things emerge: a. A preference for 'Yahweh' in an Israelite context and Elohim elsewhere. Chapters 1:1-4:5 could be a textbook example of this rule, since the name Yahweh is in sole possession of the opening episodes, which concern the prophet's adventures, occurring 19 times in the 30 verses 1:1-3:3, but is immediately replaced by Elohim (used absolutely) in 3:5-10 (5 occurrences), where Nineveh repents of its 'evil way' and its 'violence' (3:8) in response to a divine but not specifically Yahwistic message, As soon as Jonah regains the limelight, the name Yahweh reappears, dominating 4:1-4. b. Limits to this preference. The pattern breaks up at 4:6, where with 'Yahweh Elohim' the two terms stand together; after which Elohim has dealings with Jonah (7-9) which Yahweh completes (10f.). No theological motive is apparent

THE DISTRIBUTION OF DIVINE NAMES IN JONAH

127

here, for the terms cut across the expected boundaries. Yahweh Elohim could be an evocation of Genesis 2, a passage possibly relevant to the miraculous provision of the sheltering plant; yet this is merely the second special providence in a series of four, of which 'Yahweh' was designated the author of the first (1:17 (MT 2:1)) and Elohim that of the last two (4:7, 8). Again, Jonah's estrangement from the LORD might be thought to be emphasized by the change to the more distant term Elohim in 4:7-9, were it not that the name Yahweh reappears in 4:10 immediately after Jonah's second and stronger outburst. Even the question 'Do you do well to be angry?' is prefaced once by 'Yahweh' and once by Elohim. At this point the suspicion may arise that the authorship of Jonah is composite, or its text disturbed. Both views have been taken. The most thoroughgoing source-analysis was that of W. Bhme in 1887, who postulated at least five contributors: a Yahwist, an Elohist, an Elohistic Redactor, a Yahwistic supplementer and one or more glossators. While this conclusion was too elaborate to command support (and incidentally. suffered the embarrassment of having to attribute the Elohim verses, 4:7, 9, to the Yahwist), similar attempts have been equally unable to win favour, and the consensus is that the book cannot be parcelled out among Yahwistic and Elohistic authors. The text of 4:7ff., however, in the ancient versions, shows some divergences from the MT in the terms used for God. While the LXX agrees with MT over these terms throughout this section, Codex Alexandrinus, Codex Marchalianus and a few of the cursive MSS of the LXX add or substitute at some points in these verses where is otherwise found. The Old Latin and the Vulgate show the same tendency, and the Peshitta gives the equivalent of Yahweh Elohim throughout 6-9. J. A. Bewer (ICC, 1912) uses these data not as direct evidence of what stood in the earliest Hebrew text, but as indications of the direction in which copyists (including, by inference, copyists of the pre-Massoretic text) tended to corrupt this passage. Some translators and copyists of the Versions, coming to the unexpected word 'God' in 4:6-9, seem to have yielded to the pull of 'Lord', from the verses before, and substituted or

128

TYNDALE BULLETIN

added it. 'The process', says Bewer, 'was the same in Heb. MSS. . . . Our author did not write [Yahweh Elohim in verse 6], he wrote simply . A copyist, or reader, under the influence of ch. 3 wrote probably all through ch. 4, but in some instances the orig. readings reasserted themselves. But this reasoning is most precarious. Not only does Bewer reverse the direction of change (which ran from 'God' to Lord in the versions, but from 'Lord' to 'God' in this reconstruction of the Hebrew), but he extends the supposed corruption to the whole chapter before wiping out its traces in all but verses 6-10. This he has to do, to make the postulated intrusion of Elohim plausible; but his theory has outrun his data. We are brought, it seems, back to the MT, with a heightened recognition of the author's occasional independence of his general procedure. This establishes as our third finding: c. The author's literary freedom. On the evidence as we have it, the book of Jonah shows a responsible but not hidebound attitude to the distinctions implied in its two main terms for God. On the whole (and this means for more than nine-tenths of the book) the theme of Israel and the Nations closely controls the choice of one term or the other as appropriate to the more intimate or the more general relationship of God to man. To a large extent this rationale can be discerned in Pentateuchal usage as well. But the purely aesthetic impulse towards variety of language also asserts itself, freeing the narrator from undue bondage to his rules, and at the same time reminding the reader that the names are in the last resort interchangeable, common to the one Yahweh Elohim. And this too is not irrelevant to Pentateuchal studies.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Swetnam, JamesDokumen20 halamanSwetnam, JamesalfalfalfBelum ada peringkat

- Enriching Your Prayers: Vol 1, Praying Genesis Through Joshua: Praying Through the Bible, #1Dari EverandEnriching Your Prayers: Vol 1, Praying Genesis Through Joshua: Praying Through the Bible, #1Belum ada peringkat

- Yahweh The DestroyerDokumen31 halamanYahweh The DestroyerRomeBelum ada peringkat

- 10 Questions and Answers on Jehovah's Witnesses: Key Beliefs, Practics, and HistoryDari Everand10 Questions and Answers on Jehovah's Witnesses: Key Beliefs, Practics, and HistoryBelum ada peringkat

- The Christological and Trinitarian Role of Kurios in the New TestamentDokumen63 halamanThe Christological and Trinitarian Role of Kurios in the New TestamentKi C PungitBelum ada peringkat

- Bethel and The Persistence of El: Evidence For The Survival of El As An Independent Deity in The Jacob Cycle and 1 Kings 12:25-30Dokumen17 halamanBethel and The Persistence of El: Evidence For The Survival of El As An Independent Deity in The Jacob Cycle and 1 Kings 12:25-30OLEStarBelum ada peringkat

- GOD, God, god, LORD, Lord and lord in the BibleDokumen4 halamanGOD, God, god, LORD, Lord and lord in the BibleRahim4411Belum ada peringkat

- God and The Sea in Job 38: Collin Robinson CornellDokumen16 halamanGod and The Sea in Job 38: Collin Robinson CornellSam Lau Yiu SangBelum ada peringkat

- The Pronunciation of God's Divine NameDokumen32 halamanThe Pronunciation of God's Divine NameJoachim Petrolino100% (2)

- Let'S Study: OnkelosDokumen3 halamanLet'S Study: Onkelosoutdash2Belum ada peringkat

- Heaven Opened - Intertextuality and Meaning in John 1.51Dokumen20 halamanHeaven Opened - Intertextuality and Meaning in John 1.51Ricardo Santos SouzaBelum ada peringkat

- The Theological Understanding of Trinity Its Implication To Contemporary ChurchDokumen34 halamanThe Theological Understanding of Trinity Its Implication To Contemporary ChurchTheophilus KhualBelum ada peringkat

- PRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENDokumen12 halamanPRONOUNCEDASITISWRITTENCadena CadenaBelum ada peringkat

- The Language of Doxology in Aramaic DanielDokumen15 halamanThe Language of Doxology in Aramaic DanielTrevor PetersonBelum ada peringkat

- The Word of God - 4.12-13Dokumen23 halamanThe Word of God - 4.12-1331songofjoy100% (1)

- God's Victory Over Chaos in Genesis 1Dokumen20 halamanGod's Victory Over Chaos in Genesis 1abbraxasBelum ada peringkat

- GOD AS FATHER in Old Testament and in Matthew - From BOOK PENNINGTONDokumen35 halamanGOD AS FATHER in Old Testament and in Matthew - From BOOK PENNINGTONbabiboiban100% (1)

- The Two Yahwehs & Their NamesDokumen6 halamanThe Two Yahwehs & Their NamesyenoBelum ada peringkat

- Hebrews and The TrinityDokumen14 halamanHebrews and The Trinitysbob255Belum ada peringkat

- 23-The Yahweh Speeches in The Book of JobDokumen14 halaman23-The Yahweh Speeches in The Book of JobFirmino de Oliveira FialhoBelum ada peringkat

- The Nature of God in The Pentateuch: Why God Is Not An Angry TeenagerDokumen10 halamanThe Nature of God in The Pentateuch: Why God Is Not An Angry TeenagerDrew Dixon100% (1)

- Article 24Dokumen28 halamanArticle 24alfalfalfBelum ada peringkat

- DEUT 27 - BarkerDokumen27 halamanDEUT 27 - BarkerTimotius Avent JordanBelum ada peringkat

- The Name of YhwhDokumen4 halamanThe Name of YhwhJessie Bechayda100% (1)

- 2 Baruch, 4 Ezra, and The Epistle To The Hebrews - Three Approaches To The Interpretation of Psalm 104 - MasonDokumen11 halaman2 Baruch, 4 Ezra, and The Epistle To The Hebrews - Three Approaches To The Interpretation of Psalm 104 - MasonJaime HancockBelum ada peringkat

- Torah 101-Terumah Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (Mishpatim)Dokumen5 halamanTorah 101-Terumah Parsha I. Answers To Study Questions (Mishpatim)api-204785694Belum ada peringkat

- ETS 2010 Psalm 82 As Men or Divine Beings? (Michael Heiser)Dokumen14 halamanETS 2010 Psalm 82 As Men or Divine Beings? (Michael Heiser)kicker_jesus100% (1)

- The Context of The Crux at Hebrews 5,7-8 (James Swetnam) RevDokumen20 halamanThe Context of The Crux at Hebrews 5,7-8 (James Swetnam) RevJaguar777xBelum ada peringkat

- Revealing the Sacred Name YHWHDokumen18 halamanRevealing the Sacred Name YHWHounbblBelum ada peringkat

- Christology in The Early ChurchDokumen12 halamanChristology in The Early ChurchBoki KinnyBelum ada peringkat

- Notas The Context of The Crux at Hebrews 5,7-8Dokumen20 halamanNotas The Context of The Crux at Hebrews 5,7-8levBelum ada peringkat

- The Name of God Y.eH .Ow .Ah Which Is Pron PDFDokumen70 halamanThe Name of God Y.eH .Ow .Ah Which Is Pron PDFChristopher Evenhus100% (1)

- John P. Meier (1985) - Structure and Theology in Heb 1,1-14. Biblica 66.2, Pp. 168-189Dokumen23 halamanJohn P. Meier (1985) - Structure and Theology in Heb 1,1-14. Biblica 66.2, Pp. 168-189Olestar 2023-06-22Belum ada peringkat

- The LORD Will Help His Servant An ExegesDokumen15 halamanThe LORD Will Help His Servant An ExegesDoruBelum ada peringkat

- Job'S New Beginning: Chapter 42, Vv. 10-17Dokumen5 halamanJob'S New Beginning: Chapter 42, Vv. 10-1719.3521 Jeremia S.T LbntobingBelum ada peringkat

- The Trinity in CreationDokumen12 halamanThe Trinity in CreationPadre Luciano Couto, ccnBelum ada peringkat

- Who Is The Holy One PDFDokumen20 halamanWho Is The Holy One PDFRoberto FortuBelum ada peringkat

- The Divine Council - Reimagining AuthorityDokumen21 halamanThe Divine Council - Reimagining AuthorityDeepak M. BabuBelum ada peringkat

- Reading: "The Names of God" by Edward Mack ISBEDokumen32 halamanReading: "The Names of God" by Edward Mack ISBEBenjaminFigueroaBelum ada peringkat

- I Am - Divine Name Essay 1Dokumen8 halamanI Am - Divine Name Essay 1api-264767612Belum ada peringkat

- Worship Him For Who and What He Has DoneDokumen11 halamanWorship Him For Who and What He Has DoneEunji N JeffBelum ada peringkat

- Article 180 PDFDokumen16 halamanArticle 180 PDFPaz NewmanBelum ada peringkat

- ''Let All God's Angels Worship Him'' - Gordon AllanDokumen8 halaman''Let All God's Angels Worship Him'' - Gordon AllanRubem_CLBelum ada peringkat

- GreekSyntaxandtheTrinity AubreyDokumen8 halamanGreekSyntaxandtheTrinity AubreyNickNorelliBelum ada peringkat

- Bara Biblical Word StudyDokumen4 halamanBara Biblical Word StudyRudaBelum ada peringkat

- 2cor 44 PDFDokumen22 halaman2cor 44 PDFsandocan RombosBelum ada peringkat

- God Use and MeaningDokumen8 halamanGod Use and MeaningBiblical-monotheismBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 13. - Revealed Theology. God and His Attributes.: SyllabusDokumen11 halamanLecture 13. - Revealed Theology. God and His Attributes.: Syllabustruthwarrior007Belum ada peringkat

- Jackson Isa MalDokumen18 halamanJackson Isa MalAugustine RobertBelum ada peringkat

- God's Name Paradox Revealed in Ancient ScriptsDokumen68 halamanGod's Name Paradox Revealed in Ancient ScriptsRubem_CL100% (3)

- EXPOSITORYDokumen8 halamanEXPOSITORYErwin Mark PobleteBelum ada peringkat

- THEOLOGICAL Dictionary of The New Testament PDFDokumen1.235 halamanTHEOLOGICAL Dictionary of The New Testament PDFCosmin Dorobăţ91% (11)

- Let Us Strive To Enter That Rest The Logic of Hebrews 4-1-11Dokumen11 halamanLet Us Strive To Enter That Rest The Logic of Hebrews 4-1-11JoshuaJoshuaBelum ada peringkat

- 09 Habacuc - Habakkuk 2 4b in Its Context How Far Off Was Paul - Debbie HunnDokumen22 halaman09 Habacuc - Habakkuk 2 4b in Its Context How Far Off Was Paul - Debbie HunnLuisbrynner AndreBelum ada peringkat

- Esoteric Hebrew Names of God (Printer Version)Dokumen9 halamanEsoteric Hebrew Names of God (Printer Version)Joshua Thangaraj Gnanasekar100% (1)

- The Restrainer: Answering Ten Questions in Order To Interpret 2 Thessalonians 2.6-8aDokumen16 halamanThe Restrainer: Answering Ten Questions in Order To Interpret 2 Thessalonians 2.6-8aVitor MachadoBelum ada peringkat

- Job As Paradigm For The EschatonDokumen15 halamanJob As Paradigm For The EschatonCases M7Belum ada peringkat

- The Name of The FatherDokumen5 halamanThe Name of The FatherAzriel100% (1)

- How To Choose A Study Bible by John R Kohlenberger III PDFDokumen12 halamanHow To Choose A Study Bible by John R Kohlenberger III PDFAnthony D'AngeloBelum ada peringkat

- 2014-08-11 - Puerto-Rico-Final (Pew Research) PDFDokumen40 halaman2014-08-11 - Puerto-Rico-Final (Pew Research) PDFRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- Using PortfoliosDokumen76 halamanUsing PortfoliosRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- VulgataDokumen799 halamanVulgataRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- Tutoriales CANVAS Instructure PDFDokumen1 halamanTutoriales CANVAS Instructure PDFRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- 4-3 - Young (The Authorship of Isaiah)Dokumen6 halaman4-3 - Young (The Authorship of Isaiah)Roberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- 2014-08-11 - Puerto-Rico-Final (Pew Research) PDFDokumen40 halaman2014-08-11 - Puerto-Rico-Final (Pew Research) PDFRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- The Holy Bible A Buyers Guide 2013Dokumen60 halamanThe Holy Bible A Buyers Guide 2013wilfredo torresBelum ada peringkat

- 4-3 - Young (The Authorship of Isaiah)Dokumen6 halaman4-3 - Young (The Authorship of Isaiah)Roberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- (Abraham) Kuyper - Encyclopedia of Sacred TheologyDokumen499 halaman(Abraham) Kuyper - Encyclopedia of Sacred TheologyRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- The Gospel According To St. John, English Version, B. F. Westcott, 1892Dokumen416 halamanThe Gospel According To St. John, English Version, B. F. Westcott, 1892David Bailey100% (1)

- Young Days1a WTJDokumen34 halamanYoung Days1a WTJRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- Ernst Würthwein-THE TEXT OF THE OLD TESTAMENTDokumen309 halamanErnst Würthwein-THE TEXT OF THE OLD TESTAMENTRoberto Gerena100% (1)

- John BarrettDokumen17 halamanJohn BarrettEmily MaxwellBelum ada peringkat

- VulgataDokumen799 halamanVulgataRoberto GerenaBelum ada peringkat

- English Iii-Literary Musings: A Valediction: Forbidding MourningDokumen10 halamanEnglish Iii-Literary Musings: A Valediction: Forbidding MourningWungreiyon moinao100% (1)

- Jalal Toufic, Forthcoming, 2nd EditionDokumen151 halamanJalal Toufic, Forthcoming, 2nd EditionCarlos ServandoBelum ada peringkat

- Full Download Test Bank For Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing 10th Edition Gail Stuart PDF Full ChapterDokumen34 halamanFull Download Test Bank For Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing 10th Edition Gail Stuart PDF Full Chaptergenevieveprattgllhe100% (16)

- The Poetry of Robert FrostDokumen41 halamanThe Poetry of Robert FrostRishi JainBelum ada peringkat

- Arabian LiteratureDokumen9 halamanArabian LiteratureNino Joycelee TuboBelum ada peringkat

- ArdiDokumen15 halamanArdiegyadyaBelum ada peringkat

- Tiamat (Dungeons & Dragons) - WikipediaDokumen11 halamanTiamat (Dungeons & Dragons) - Wikipediajorge solieseBelum ada peringkat

- A Roadside Stand by Robert FrostDokumen5 halamanA Roadside Stand by Robert FrostShivanshi Bansal100% (1)

- Glory of Sanskrit by Scholars of WorldDokumen72 halamanGlory of Sanskrit by Scholars of WorldvedicsharingBelum ada peringkat

- Narrative Paragraph LessonDokumen13 halamanNarrative Paragraph LessonJennifer R. Juatco100% (1)

- I) External Pieces of EvidenceDokumen5 halamanI) External Pieces of EvidenceJohn WycliffeBelum ada peringkat

- African Literature - 21st Century LiteratureDokumen3 halamanAfrican Literature - 21st Century LiteratureJohannaHernandezBelum ada peringkat

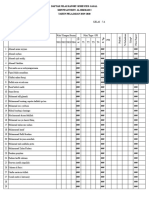

- Format Nilai 2019Dokumen24 halamanFormat Nilai 2019Haji Su'ebBelum ada peringkat

- Engage Students in Learning About Environment Through Creative Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanEngage Students in Learning About Environment Through Creative Lesson PlanSusila PonnusamyBelum ada peringkat

- Faerie Queen As An AllegoryDokumen3 halamanFaerie Queen As An AllegoryAngel Arshi89% (19)

- Worksheet 10 Differentiation 4Dokumen2 halamanWorksheet 10 Differentiation 4Chandra SekarBelum ada peringkat

- The Thursday Murder Club: The Record-Breaking Sunday Times Number One Bestseller - Richard OsmanDokumen6 halamanThe Thursday Murder Club: The Record-Breaking Sunday Times Number One Bestseller - Richard Osmanjinecere6% (157)

- Sijo PoetryDokumen16 halamanSijo PoetryAlmina15Belum ada peringkat

- Mini Tafseer Book Series Suratul-Faatiha Sample2 PDFDokumen14 halamanMini Tafseer Book Series Suratul-Faatiha Sample2 PDFMoin Ahmed50% (2)

- Massimo Cacciari, 1994. The Necessary AngelDokumen133 halamanMassimo Cacciari, 1994. The Necessary AngelAbner J ColmenaresBelum ada peringkat

- SOAL UTS 1 BASA JAWA KELAS XIDokumen7 halamanSOAL UTS 1 BASA JAWA KELAS XIUmu ChabibahBelum ada peringkat

- Early Modern: Humanism and The English Renaissance and The Print RevolutionDokumen9 halamanEarly Modern: Humanism and The English Renaissance and The Print RevolutionAnanyaRoyPratiharBelum ada peringkat

- Larkin and Duffy ContextDokumen5 halamanLarkin and Duffy ContextIlham YUSUFBelum ada peringkat

- Ekphrastic LessonDokumen17 halamanEkphrastic Lessonmappari1227Belum ada peringkat

- Cable OperatorsDokumen10 halamanCable OperatorsSkspBelum ada peringkat

- Komunitas K-Pop di Sidoarjo 2013-2018Dokumen2 halamanKomunitas K-Pop di Sidoarjo 2013-2018Dewi AisyahBelum ada peringkat

- Western Civilization: Ch. 3Dokumen7 halamanWestern Civilization: Ch. 3LorenSolsberry67% (3)

- Template Nilai Sumatif-X.AGAMA.1-Ilmu Tafsir.Dokumen90 halamanTemplate Nilai Sumatif-X.AGAMA.1-Ilmu Tafsir.backupismailrozi1Belum ada peringkat

- Dwnload Full Genetics Analysis and Principles 5th Edition Brooker Test Bank PDFDokumen35 halamanDwnload Full Genetics Analysis and Principles 5th Edition Brooker Test Bank PDFzaridyaneb100% (6)

- PHD Thesis University of PretoriaDokumen8 halamanPHD Thesis University of Pretoriabsqw6cbt100% (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDari EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (3)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonDari EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1477)

- The Wim Hof Method: Activate Your Full Human PotentialDari EverandThe Wim Hof Method: Activate Your Full Human PotentialPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Conversations with God: An Uncommon Dialogue, Book 1Dari EverandConversations with God: An Uncommon Dialogue, Book 1Penilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (66)

- The Happy Medium: Life Lessons from the Other SideDari EverandThe Happy Medium: Life Lessons from the Other SidePenilaian: 2.5 dari 5 bintang2.5/5 (2)

- Notes from the Universe: New Perspectives from an Old FriendDari EverandNotes from the Universe: New Perspectives from an Old FriendPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (53)

- The Book of Shadows: Discover the Power of the Ancient Wiccan Religion. Learn Forbidden Black Magic Spells and Rituals.Dari EverandThe Book of Shadows: Discover the Power of the Ancient Wiccan Religion. Learn Forbidden Black Magic Spells and Rituals.Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Between Death & Life: Conversations with a SpiritDari EverandBetween Death & Life: Conversations with a SpiritPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (179)

- My Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksDari EverandMy Spiritual Journey: Personal Reflections, Teachings, and TalksPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (26)

- The Essence of the Bhagavad Gita: Explained by Paramhansa Yogananda as remembered by his disciple, Swami KriyanandaDari EverandThe Essence of the Bhagavad Gita: Explained by Paramhansa Yogananda as remembered by his disciple, Swami KriyanandaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (39)

- The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingDari EverandThe Art of Happiness: A Handbook for LivingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1205)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthDari EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (179)

- Adventures Beyond the Body: How to Experience Out-of-Body TravelDari EverandAdventures Beyond the Body: How to Experience Out-of-Body TravelPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (19)

- It's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessDari EverandIt's Easier Than You Think: The Buddhist Way to HappinessPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (60)

- Seven Sermons to the Dead: Septem Sermones ad MortuosDari EverandSeven Sermons to the Dead: Septem Sermones ad MortuosPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (31)

- The Artisan Soul: Crafting Your Life into a Work of ArtDari EverandThe Artisan Soul: Crafting Your Life into a Work of ArtPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (10)

- Proof of Life after Life: 7 Reasons to Believe There Is an AfterlifeDari EverandProof of Life after Life: 7 Reasons to Believe There Is an AfterlifePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (5)

- Paul Was Not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood ApostleDari EverandPaul Was Not a Christian: The Original Message of a Misunderstood ApostlePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (13)

- George Müller: The Guardian of Bristol's OrphansDari EverandGeorge Müller: The Guardian of Bristol's OrphansPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (27)

- Wisdom Distilled from the Daily: Living the Rule of St. Benedict TodayDari EverandWisdom Distilled from the Daily: Living the Rule of St. Benedict TodayPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (25)

- A New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodeDari EverandA New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (4)