610376

Diunggah oleh

Fiqih IbrahimHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

610376

Diunggah oleh

Fiqih IbrahimHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Somatoform and Psychoform Dissociation Among Students

Benedetto Farina, 1,2 Eva Mazzotti, 3,4 Paolo Pasquini, 5 Ellert Nijenhuis, 6 and Massimo Di Giannantonio 7

1 2

Universita` Europea di Roma, School of Psychology, Rome, Italy Centro Clinico de Sanctis, Rome, Italy 3 Divisione di Oncologia e Dermatologia Oncologica, IDI-IRCCS, Rome, Italy 4 SPAD - Scuola di Psicoterapia dellAdolescenza e dellEta` Giovanile, Rome, Italy 5 Unita` di Epidemiologia, IDI-IRCCS, Rome, Italy 6 Top Referent Trauma Center GGZ Drenthe, Assen, Netherlands 7 Universita` DAnnunzio, Faculty of Psychology, Chieti, Italy

Recent evidence suggests a relationship between psychoform and somatoform dissociation both in clinical and non clinical samples. The aim of the study was to investigate the association between the two forms of dissociation among 947 university students who completed two self-administered questionnaires, the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20) and the Dissociative Experience Scale (DES). The main result of the study was that the association between somatoform and psychoform dissociation was strong for individuals with moderate level of DES scores (O.R. 5 7.0), but much stronger for individuals with high level of DES scores (O.R. 5 18.9). & 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J Clin Psychol 67:665672, 2011. Keywords: DES-taxon; psychoform dissociation; questionnaires; somatoform dissociation

Dissociative disorders and somatoform disorders are classied by DSM-IV in two distinct categories (APA, 2000). However, it has been observed from the second half of the 19th century that dissociation can pertain to the mind and body (Janet, 1889, 1907; van der Kolk & van der Hart, 1989). In keeping with this, the dissociative disorders in ICD-10 (WHO, 1992) include dissociative disorders of movement and sensation. Dissociative symptoms that phenomenologically involve the body are called somatoform; dissociative symptoms that phenomenologically involve the mind are called psychoform (Nijenhuis, 2009). The labels psychoform dissociation and somatoform dissociation should not be taken to mean that only psychoform dissociation is of a mental nature. Both adjectives refer to manifestations of the existence of a dissociation of the personality as a whole dynamic biopsychosocial system into two or more insufciently integrated subsystem (Nijenhuis & Van der Hart, in press; van der Hart, Nijenhuis, & Steele, 2006). The complexity of this dissociation of the personality varies, and is associated with different degrees of psychoform and somatoform dissociative symptoms. Negative dissociative symptoms pertain to apparent losses such as losses of memory, motor control, skills, and somatosensory awareness. For example, negative psychoform dissociative symptoms include dissociative amnesia as well as dissociative loss of affect and will, and negative somatoform dissociative symptoms dissociative analgesia, anesthesia and loss of motor control, such as dissociative aphonia. Positive dissociative symptoms involve intrusions, and are common in dissociative disorders (Dell, 2006; Nijenhuis, 2009). These symptoms include, among others, dissociative ashbacks and full reexperiencing of traumatizing events, as well as intruding voices, thoughts, movements, and emotional or physical feelings, including pain. Consistent with the hypothesis that psychoform and somatoform dissociation are both manifestations of a division of personality, these two groups of symptoms were correlated

This article was reviewed and accepted under the editorship of Beverly E. Thorn.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to: Eva Mazzotti, Divisione di Oncologia e Dermatologia Oncologica, Istituto Dermopatico dellImmacolata, IDI-IRCCS, Via dei Monti di Creta, 104, 00100 Rome, Italy; e-mail: eva.mazzotti@tiscali.it JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY, Vol. 67(7), 665--672 (2011) & 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/jclp). DOI: 10.1002/jclp.20787

666

Journal of Clinical Psychology, July 2011

phenomena in various clinical samples (Nijenhuis, 2009; Ross, Heber, Norton, & Anderson, 1989; Saxe et al., 1994) and in general population samples (Maaranen, Tanskanen, Haatainen et al., 2005). Compared to subjects with lower psychoform and/or somatoform dissociation scores, subjects with high psychoform and somatoform dissociation scores showed differences in psychiatric, physical, psychological, social, and socio-economic variables (Maaranen et al., 2004). Following Janet (Janet, 1907; van der Kolk & van der Hart, 1989), several contemporary authors have hypothesized that dissociation of the personality relates to combination of subjective and objective factors. These include exposure to adverse events, particularly when these are socially hidden and involve signicant others (e.g., parents), lack of integrative capacity (e.g., due to psychobiological immaturity), lack of affect regulation by signicant others, and attachment disruptions, particularly in the form of disorganized attachment (Liotti, 2006; van der Hart et al., 2006). Van der Kolk and colleagues found that dissociation of consciousness, somatization and affective dysregulation are the major clinical features of prolonged trauma during childhood (van der Kolk et al., 1996; van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday, & Spinazzola, 2005). A relationship between exposure to potentially traumatizing events such as adverse early relational experiences and dissociative symptoms (both psychoform and somatoform) has been demonstrated (Chu & Dill, 1990; Liotti, 2006; Mulder, Beautrais, Joyce, & Fergusson, 1998; Nijenhuis, 2009; Ozturk & Sar, 2008; Pasquini, Liotti, Mazzotti, Fassone, & Picardi, 2002; Roelofs, Keijsers, Hoogduin, Naring, & Moene, 2002; Sar, Akyuz, Kundakci, Kiziltan, & Dogan, 2004; van der Hart et al., 2006). For example, the link between somatoform dissociation and reported potentially traumatizing events has also been documented in patients with chronic pelvic pain, and in general population and university student samples (Maaranen et al., 2004; Naring & Nijenhuis, 2005; Nijenhuis et al., 2003). Diseth (Diseth, 2006) demonstrated in a longitudinal prospective study that somatoform dissociation in adolescence and early adulthood was best predicted by a traumatizing longterm medical treatment in early childhood that included the parents, and that it was also a good predictor of psychoform dissociation. It can be speculated that involvement of the parents in this treatment was traumatizing in itself (e.g., painful daily insertion of anal dilatators), and also compromised secure attachment. In two prospective, longitudinal studies, a link between attachment disruptions in childhood and later dissociative symptoms has been documented (Dutra, Bureau, Holmes, Lyubchik, & Lyons-Ruth, 2009; Ogawa, Sroufe, Weineld, Carlson, & Egeland, 1997). Reinders et al. (Reinders et al., 2006) showed that two different types of dissociative parts of the personality in patients with dissociative identity disorder (APA, 1994) have very different sensorimotor, emotional, psychophysiological and neural reaction patterns to personalized trauma scripts. Neither high nor low fantasy prone healthy women were able to simulate these reactions (Reinders et al., 2006). These ndings indicate that complex dissociative disorders are not due to sociocognitive factors but relate to traumatization. The severity of psychoform dissociation is commonly evaluated with the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES) (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986). However, there is concern that this selfreport questionnaire includes items that do not pertain to dissociation of the personality but involve different alterations of consciousness such as absorption and retracted consciousness (van der Hart, Nijenhuis, Steele, & Brown, 2004). Somatoform dissociation is measured with the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20) (Nijenhuis, Spinhoven, Van Dyck, Van der Hart, & Vanderlinden, 1996). All items of this self-report questionnaire were designed to measure somatoform manifestations of the existence of a dissociation of the personality. Absorption and selective attention are phenomena that are common in the general population and in psychiatric patients, whereas dissociation of the personality characterizes patients with dissociative disorders. It can thus be hypothesized that low levels of psychoform dissociation and somatoform dissociation are less strongly correlated than high levels of psychoform dissociation and somatoform dissociation. The aims of the current study were (a) to estimate the prevalence of somatoform dissociation (SDQ-20) and psychoform dissociation/other alterations of consciousness (DES) in a large sample of Italian university students, and (b) to assess the association between these

Dissociative Phenomena Among Students

667

two different phenomenological kinds of dissociative symptoms at different levels of severity, thus testing the hypothesis that the strength of the association increases with increasing SDQ-20 and DES scores.

Methods

Our sample consisted of 1,290 undergraduate students enrolled at Chieti University, School of Psychology. Of the whole, 1,020 (79%) anonymously completed and returned the two questionnaires. To restrict the age range, we excluded 25 subjects (2,5%) older than 28 years (aged between 29 and 56 years). Participants (N 5 995) were aged between 18 and 28 years (mean age 5 20.6, standard deviation, SD 5 1.5; median 5 20). Eighty-three percent were females (N 5 827). Less than 2% (N 5 14) were married. No differences were observed between included and excluded subjects regarding gender, DES and SDQ-20 scores.

Assessment Instruments

The 20-item Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (Nijenhuis et al., 1996) is a selfadministered instrument that evaluates the severity of somatoform dissociation. The SDQ-20 assesses positive symptoms as site-specic pain (sometimes I have pain while urinating) and negative symptoms as blindness, impairment of auditory perception, motor inhibitions, kinesthetic anesthesia and analgesia (sometimes my body, or a part of it, is insensitive to pain). Items are answered on a ve-point scale, ranging from 1 5 this applies to me not at all to 5 5 this applies to me extremely. Items are summed to provide a total score (range 20100). Subjects were asked to respond with reference to a time frame of the preceding 12 months. In this study the internal consistency of the scale was high (a 5 0.80). The Dissociative Experiences Scale (Bernstein & Putnam, 1986) is a 28-item selfadministered inventory to measure the frequency of dissociative experiences. To answer DES questions, subjects circle the percentage of time (given in 10% increments ranging from 0 to 100) that they have the experience described. A subset of eight items of the DES, the so-called DES-Taxon (DES-T) (Waller, Putnam, & Carlson, 1996), is thought to be especially sensitive to identify pathological dissociation. The DES-T total score can be obtained by averaging across DES items 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 22, and 27. In this study we used the Italian version of the DES (Mazzotti & Cirrincione, 2001). Subjects were asked to respond with reference to a time frame of the preceding 12 months. In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was high (DES, a 5 0.92; DES-T, a 5 0.76). Information about gender, age and marital status were also collected. The study procedure was in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA, version 9.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Tex), with statistical signicance set at po0.05. Cases of high somatoform dissociation were operationally dened as subjects scoring Z35 for SDQ-20 (Sar, Tutkun, Alyanak, Bakim, & Baral, 2000). According to previous research (Maaranen, Tanskanen, Haatainen et al., 2005; Waller, Ohanian, Meyer, Everill, & Rouse, 2001; Waller & Ross, 1997) a cutoff Z20 in DES-T has been choose to discriminate subjects with dissociative disorders. For the purposes of the analysis, the DES-T score was divided into four categories according to its quartile scores. The rst category (DES-T scores o2.5) was used as reference, the second (2.55.0) was labeled mild DES-T scores, the third (5.112.5) was denominated moderate DES-T scores, and the fourth (412.5) was denominated high DES-T scores. Cronbachs alpha was used to assess internal consistency of the scales. Owing to nonnormality of the SDQ-20 and DES data, Spearman rank correlations and Mann-Whitney U-test were calculated. Crude and adjusted Odds Ratios (O.R.) with 95% condence intervals

668

Journal of Clinical Psychology, July 2011

(CI) were calculated to study the association between selected variables and the propensity to high somatoform dissociation (SDQ-20Z35). To test if the effect of the psychoform dissociation (DES-T) on the high somatoform dissociation would increase systematically with the level of exposure we included DES-T categories as an ordinal variables in the logistic regression and tested for trend (Wald test). The scores for 48 questionnaires, involving 48 participants, were excluded because of missing values. Analyses were conducted on a sample of 947 students.

Results

As expected, the SDQ-20 and DES scores were not normally distributed (z Shapiro-Wilk test 5 11.9 and 10.1, respectively; po0.001). The median SDQ-20 score was 23 (range 2078; mean 5 24.6; SD 5 5.5). The median DES score was 13.6 (range 080; mean 5 16.7; SD 5 12.0). The median DES-T score was 5.0 (range 076; mean 5 8.9; SD 5 10.4). No signicant differences were observed for males and females regarding their SDQ-20, DES and DES-T scores. The correlations between SDQ-20 and DES, and SDQ-20 and DES-T scores were both 0.40 (p-valueo0.001). Prevalence of high somatoform dissociation (SDQ-20Z35) was 4.7%, it was 2.6% in males and 5.1% in females (p 5 0.171). Prevalence of psychoform dissociation (DES-TZ20) was 12.9%, it was 19.1% in males and 11.7% in females (p 5 0.011). High somatoform dissociation and psychoform dissociation were strongly associated (age and gender adjusted O.R. 5 10.2; 95% C.I. 5 5.319.3). In order to explore this association, we rst examined the differences of SDQ-20 median scores among the DES-T categories and found a signicant difference (po0.001, data not shown). Next, we studied the association between somatoform dissociation and the DES-T categories. As shown in Table 1, we observed an increasing propensity to high somatoform dissociation for higher levels of DES-T scores (test for trend, po0.001). This association was rather strong (O.R. 5 7.0; 95% CI 5 1.631.6) at the level of moderate DES-T scores, and much stronger in high DES-T scores (O.R. 5 18.9; 95% CI 5 4.481.5).

Discussion

The DES median score (13.6) in the present sample of university students was consistent with those reported in other studies including student samples (Armando et al., 2008; Mazzotti & Cirrincione, 2001; Putnam et al., 1996). The general relationship between DES and SDQ-20 scores was comparable with that reported by Maaranen et al. (2005). The prevalence of pathological psychoform dissociation (DES-TZ20) in our study was 12.9% and that of high somatoform dissociation (SDQ-20Z35) 4.7%. We also found that pathological dissociators were signicantly more frequent among male students compared to female students. The prevalence of pathological psychoform dissociation in the general

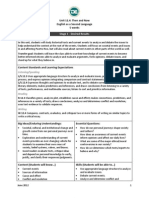

Table 1

Association Between Somatoform Dissociation (SDQ-20, No-Cases; cases) and DES-T Categories

SDQ-20 No-cases DES-T reference mild moderate high N (%) 230 265 216 192 (25.5) (29.4) (23.9) (21.3) Cases N (%) 2 2 13 27 (4.6) (4.6) (29.6) (61.4) OR 1.00 0.87 6.92 16.17 95% CI 0.126.21 1.5431.03 3.8068.88 OR 1.00 0.88 7.03 18.93 95% CI 0.126.30 1.5631.63 4.4081.48 p^ o0.001

Gender and age-adjusted odds ratio. ^Test for trend (Wald test).

Dissociative Phenomena Among Students

669

population was estimated to range between 0.8 and 3.4% (Maaranen et al., 2004; Maaranen, Tanskanen, Honkalampi et al., 2005; Spitzer et al., 2006; Waller & Ross, 1997), and no-gender differences have been found (Spitzer et al., 2006). Whereas the prevalence of pathological psychoform dissociation in the present study was much higher than in studies of the general population, the prevalence of high somatoform dissociation was lower. Using the same cut-off point (SDQ-20430), Maaranen and colleagues (Maaranen et al., 2004) documented a prevalence of 9.4% and we found a prevalence of 12.3%. As noted by Spitzer et al. (Spitzer et al., 2006), this variability in prevalence rates can in part reect differences in sampled populations as well as methodological differences (i.e., different cut-off points, subjects were not assigned taxonomic class by the statistical method recommended by Waller and Ross (Waller & Ross, 1997)). The high prevalence of pathological psychoform dissociation in our sample is hard to explain. One possibility is that motivation underlying the career choice of mental health professionals may include a desire to resolve personal psychological distress as reported in previous studies (Nikcevic, Kramolisova-Advani, & Spada, 2007). Still, the nding of a higher degree of psychoform dissociation among males in this study is remarkable but hard to interpret given that females constituted 83% of the sample. Future work will have to clarify if higher psychoform dissociation among male students was a chance nding or a common phenomenon in Italian students. The severity of somatoform dissociation was not different for males and females, and was within the expected range given the prevalence of dissociative disorders in the general population (Van der Hart & Nijenhuis, 2008). Consistent with our hypothesis, the association between somatoform and psychoform dissociation was strong (O.R. 5 7.0) and that its strength increases with high DES-T scores (O.R. 5 18.9). This new nding invites in-depth studies of the differences and relations between dissociative symptoms understood as manifestations of a division of personality and phenomena that indicate lowering and retraction of consciousness. There is an urgent need for a self-report questionnaire that specically assesses the psychoform dissociative symptoms, but that does not include items measuring lowering and retraction of consciousness. Consistent with Nijenhuis and Van der Hart (Nijenhuis & Van der Hart, in press), we hypothesize that manifestations of a division of personality are sensitive and specic for DSMIV dissociative disorders, as well as somatoform dissociative disorders, whereas lowering and retraction of consciousness is sensitive but not specic for these disorders. A debate is still open on how high dissociation should be viewed, as the extreme end of a continuum of dissociative symptoms or as a separate taxon that represents a deviation from normal development (Ogawa et al., 1997). In this regard, Putnam and colleagues (Putnam et al., 1996) found a subgroup of high dissociators among patients with signicant elevation of dissociative scores. They contended that dissociation is a discontinuous process and that a typological model, rather than a continuum model, may more accurately describe the phenomenology of pathological dissociation. In consonance with Putnam and colleagues (1996), we consider that a deviation from normal development could cause a separate taxon where the individuals integrative capacity is pathologically and structurally compromised and where psychoform and somatoform dissociation are more strongly associated. However, with Van der Hart, Nijenhuis, and Steele (2006), we contend that there is dimensionality within this taxon. Van der Hart et al. (2006) proposed that there is a dimension of complexity of dissociation of the personality. In simple dissociative disorders, the division of personality is simple. The division is more complex in more complex dissociative disorders, and more dissociative parts of the personality than in simple dissociative disorders are more elaborate and more evolved. If it would be shown that normality does not involve a (minor) division of personality, the concept of normal dissociation is better discarded. Our results are compatible with models suggesting that lack of integrative capacity in combination with other factors such as exposure to highly adverse, potentially traumatizing events, including severe attachment disruptions, and lack of interpersonal affect regulation, is a common pathogenetic feature that mediates somatoform and psychoform dissociative symptoms (Mulder et al., 1998; Nijenhuis & Van der Hart, in press; Nijenhuis, van Dyck, van der Hart, & Spinhoven, 1998; Ozturk & Sar, 2008). In this light, and given the strong association between psychoform and somatoform dissociation, conversion disorders in DSM-IV

670

Journal of Clinical Psychology, July 2011

(APA, 2000) are better conceptualized and classied as dissociative disorders in that conversion, in fact, involves somatoform dissociation. The reclassication is consonant with ICD-10 dissociative disorders of movement and sensation (WHO, 1992). Recognition of conversion as somatoform dissociation may help clinicians mind more that psychoform dissociative symptoms may also be present, that the patients personality as a whole system is dissociated into two or more subsystems, and that treatment may need to address this division of personality (Brown, Cardena, Nijenhuis, Sar, & van der Hart, 2007; Van der Hart & Nijenhuis, 2008). The study has several limitations. Our study population was that of university students of the School of Psychology in a small central Italian town (54.000 inhabitants) and may be not representative of national or regional population of students. This limitation may have affected our prevalence estimates, but much less our O.R. estimates. Although we used standardized validated questionnaires to measure somatoform and psychoform dissociation, limitations inherent in subjects self-report assessment and choice of cut-off points should be considered. Women were overrepresented, and a clinical diagnosis of dissociative or somatoform disorders was not available. Finally, we were unable to include a trauma history assessment in the current study. Future work will have to explore the inuence of factors such as personality, cognitive styles, and exposure adverse events, including attachment disruptions and emotional neglect.

Conclusion

The present study documents a strong association between somatoform and psychoform dissociation, as well as an increasing strength of this association at higher levels of these symptoms in a sample of university students. These ndings are consistent with the 19th century observation that both somatoform dissociation and psychoform dissociation are manifestations of a lack of integration at different levels of the hierarchical organization of the mind (Farina, Ceccarelli, & Di Giannantonio, 2005). Increasing evidence suggests that this lack constitutes the essence of a spectrum of trauma-related disorders (Nijenhuis, 2009; van der Hart et al., 2006). Acknowledgments Conict of interest: The authors have no conict of interest, nancial or otherwise, related to this work.

References

APA. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. APA. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-TR (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Armando, M., Fagioli, F., Borra, S., Carnevali, R., Righetti, V., Saba, R., et al. (2008). Valutazione del disagio mentale e dello stress percepito tra gli studenti universitari. Rivista di Psichiatria, 43, 292299. Bernstein, E.M., & Putnam, F.W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 4(174), 727735. Brown, R.J., Cardena, E., Nijenhuis, E., Sar, V., & van der Hart, O. (2007). Should conversion disorder be reclassied as a dissociative disorder in DSM V? Psychosomatics, 48(5), 369378. Chu, J.A., & Dill, D.L. (1990). Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(7), 887892. Dell, P.F. (2006). The multidimensional inventory of dissociation (MID): A comprehensive measure of pathological dissociation. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7(2), 77106. Diseth, T.H. (2006). Dissociation following traumatic medical treatment procedures in childhood: A longitudinal follow-up. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 233253. Dutra, L., Bureau, J.F., Holmes, B., Lyubchik, A., & Lyons-Ruth, K. (2009). Quality of early care and childhood trauma: a prospective study of developmental pathways to dissociation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(6), 383390.

Dissociative Phenomena Among Students

671

Farina, B., Ceccarelli, M., & Di Giannantonio, M. (2005). Henri Eys neojacksonism and the psychopathology of disintegrated mind. Psychopathology, 38(5), 285290. Janet, P. (1889). Lautomatisme psychologique. Paris: Felix Alcan. Janet, P. (1907). The major symptoms of hysteria. London & New York: MacMillan. Liotti, G. (2006). A model of dissociation based on attachment theory and research. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7(4), 5573. Maaranen, P., Tanskanen, A., Haatainen, K., Honkalampi, K., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Hintikka, J., et al. (2005). The relationship between psychological and somatoform dissociation in the general population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193(10), 690692. Maaranen, P., Tanskanen, A., Haatainen, K., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., Hintikka, J., & Viinamaki, H. (2004). Somatoform dissociation and adverse childhood experiences in the general population. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(5), 337342. Maaranen, P., Tanskanen, A., Honkalampi, K., Haatainen, K., Hintikka, J., & Viinamaki, H. (2005). Factors associated with pathological dissociation in the general population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(5), 387394. Mazzotti, E., & Cirrincione, R. (2001). La Dissociative Experiences Scale, esperienze dissociative in un campione di studenti italiani. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia, 1, 179192. Mulder, R.T., Beautrais, A.L., Joyce, P.R., & Fergusson, D.M. (1998). Relationship between dissociation, childhood sexual abuse, childhood physical abuse, and mental illness in a general population sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(6), 806811. Naring, G., & Nijenhuis, E.R. (2005). Relationships between self-reported potentially traumatizing events, psychoform and somatoform dissociation, and absorption, in two non-clinical populations. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(1112), 982988. Nijenhuis, E.R. (2009). Somatoform Dissociation and Somatoform Dissociative Disorders. In P. Dell & J.A. ONeil (Eds.), Dissociation and Dissociative Disorders: DSM-V and beyond. New York: Routledge. Nijenhuis, E.R., Spinhoven, P., Van Dyck, R., Van der Hart, O., & Vanderlinden, J. (1996). The development and psychometric characteristics of the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ-20). Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 184(11), 688694. Nijenhuis, E.R., & Van der Hart, O. (in press). Dissociation in trauma: A new denition and comparison with previous formulations. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation. Nijenhuis, E.R., van Dyck, R., ter Kuile, M.M., Mourits, M.J., Spinhoven, P., & van der Hart, O. (2003). Evidence for associations among somatoform dissociation, psychological dissociation and reported trauma in patients with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 24(2), 8798. Nijenhuis, E.R., van Dyck, R., van der Hart, O., & Spinhoven, P. (1998). Somatoform dissociation is unlikely to be a result of indoctrination by therapists. British Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 452. Nikcevic, A.V., Kramolisova-Advani, J., & Spada, M.M. (2007). Early childhood experiences and current emotional distress: what do they tell us about aspiring psychologists? Journal of Psychology, 141(1), 2534. Ogawa, J.R., Sroufe, L.A., Weineld, N.S., Carlson, E.A., & Egeland, B. (1997). Development and the fragmented self: longitudinal study of dissociative symptomatology in a non-clinical samples. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 855879. Ozturk, E., & Sar, V. (2008). Somatization as a predictor of suicidal ideation in dissociative disorders. Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 62(6), 662668. Pasquini, P., Liotti, G., Mazzotti, E., Fassone, G., & Picardi, A. (2002). Risk factors in the early family life of patients suffering from dissociative disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scand, 105(2), 110116. Putnam, F., Carlson, E., Ross, C., Anderson, G., Clark, P., Torem, M., et al. (1996). Patterns of dissociation in clinical and nonclinical samples. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 11(184), 673679. Reinders, A.A., Nijenhuis, E.R., Quak, J., Korf, J., Haaksma, J., Paans, A.M., et al. (2006). Psychobiological characteristics of dissociative identity disorder: a symptom provocation study. Biological Psychiatry, 60(7), 730740. Roelofs, K., Keijsers, G.P., Hoogduin, K.A., Naring, G.W., & Moene, F.C. (2002). Childhood abuse in patients with conversion disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(11), 19081913. Ross, C.A., Heber, S., Norton, G.R., & Anderson, G. (1989). Somatic symptoms in multiple personality disorder. Psychosomatics, 30(2), 154160.

672

Journal of Clinical Psychology, July 2011

Sar, V., Akyuz, G., Kundakci, T., Kiziltan, E., & Dogan, O. (2004). Childhood trauma, dissociation, and psychiatric comorbidity in patients with conversion disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(12), 22712276. Sar, V., Tutkun, H., Alyanak, B., Bakim, B., & Baral, I. (2000). Frequency of dissociative disorders among psychiatric outpatients in Turkey. Compr Psychiatry, 41(3), 216222. Saxe, G.N., Chinman, G., Berkowitz, R., Hall, K., Lieberg, G., Schwartz, J., et al. (1994). Somatization in patients with dissociative disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(9), 13291334. Spitzer, C., Barnow, S., Grabe, H., Klauer, T., Stieglitz, R., Schneider, W., et al. (2006). Frequency, clinical and demographic correlates of pathological dissociation in Europe. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7(1), 5161. van der Hart, O., & Nijenhuis, E. (2008). Dissociative Disorders. In B. P. a. M. T (Ed.), Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology. New York (USA), Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press. van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E., & Steele, K. (2006). The Haunted Self: structural dissociation and the treatment of chronic traumatization. New York, London: Norton. van der Hart, O., Nijenhuis, E., Steele, K., & Brown, D. (2004). Trauma-related dissociation: conceptual clarity lost and found. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 38(1112), 906914. van der Kolk, B.A., Pelcovitz, D., Roth, S., Mandel, F.S., McFarlane, A., & Herman, J.L. (1996). Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: the complexity of adaptation of trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(7 Suppl), 8393. van der Kolk, B.A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389399. van der Kolk, B.A., & van der Hart, O. (1989). Pierre Janet and the breakdown of adaptation in psychological trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 146(12), 15301540. Waller, G., Ohanian, V., Meyer, C., Everill, J., & Rouse, H. (2001). The utility of dimensional and categorical approaches to understanding dissociation in the eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(Pt 4), 387397. Waller, N.G., Putnam, F.W., & Carlson, E.B. (1996). Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychological Methods, 1, 300321. Waller, N.G., & Ross, C.A. (1997). The prevalence and biometric structure of pathological dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic ndings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106(4), 499510. WHO. (1992). The ICD-10 Classication of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Copyright of Journal of Clinical Psychology is the property of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- COMPARATIVE PUBLIC LAW and Research Methedology Assignment PDFDokumen2 halamanCOMPARATIVE PUBLIC LAW and Research Methedology Assignment PDFKARTHIK A0% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Decisive Chip Heath and Dan HeathDokumen1 halamanDecisive Chip Heath and Dan HeathHoratiu BahneanBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Siti Atiqah Binti Mohd Sidin A30109190004 Ess222Dokumen10 halamanSiti Atiqah Binti Mohd Sidin A30109190004 Ess222Mohd Zulhelmi Idrus100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Cyber Bullying ScriptDokumen3 halamanCyber Bullying ScriptMonica Eguillion100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Research Process Flow Chart A4 WebDokumen2 halamanResearch Process Flow Chart A4 WebEma FatimahBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Outline of Plato's Republic Book 1Dokumen2 halamanOutline of Plato's Republic Book 1priv8joy100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Marion, Jean-Luc - On The Foundation of The Distinction Between Theology and PhilosophyDokumen30 halamanMarion, Jean-Luc - On The Foundation of The Distinction Between Theology and PhilosophyJefferson ChuaBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Willy Loman As An Aristotelian Tragic HeroDokumen4 halamanWilly Loman As An Aristotelian Tragic HeroMadiBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- A Tale of Two Managers Sequel-TNDokumen3 halamanA Tale of Two Managers Sequel-TNRosarioBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Basic Concepts in Contract Drafting Vincent MartoranaDokumen92 halamanBasic Concepts in Contract Drafting Vincent MartoranaEllen Highlander100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- CH 10Dokumen17 halamanCH 10Mehmet DumanBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Levi Bryant, Nick Srnicek, and Graham Harman (Eds) : The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and RealismDokumen5 halamanLevi Bryant, Nick Srnicek, and Graham Harman (Eds) : The Speculative Turn: Continental Materialism and RealismPeterPollockBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Character and Symbol in Shakespeare 039 S Plays A Study of Certain Christian and Pre Christian Elements in Their Structure and Imagery Cambridge LiDokumen224 halamanCharacter and Symbol in Shakespeare 039 S Plays A Study of Certain Christian and Pre Christian Elements in Their Structure and Imagery Cambridge Limicuta87100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Session 5 - Marketing ManagementDokumen6 halamanSession 5 - Marketing ManagementJames MillsBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- 10 Ways To Show Good CitizenshipDokumen4 halaman10 Ways To Show Good CitizenshipJuuri KuranBelum ada peringkat

- 6-Re - Petition For Radio and T.V. Coverage A.M. No. 10-11-5-SC, A.M. No. 10-11-6-SC and A.M. No. 10-11-7-SCDokumen6 halaman6-Re - Petition For Radio and T.V. Coverage A.M. No. 10-11-5-SC, A.M. No. 10-11-6-SC and A.M. No. 10-11-7-SCFelicity HuffmanBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Essay 3Dokumen6 halamanEssay 3api-378507556Belum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- What Is Your Philosophy in LifeDokumen3 halamanWhat Is Your Philosophy in LifeArvin EleuterioBelum ada peringkat

- Modern InventionDokumen2 halamanModern InventionLiah CalderonBelum ada peringkat

- Virtue As ExcellenceDokumen2 halamanVirtue As ExcellenceMelissa AlexandraBelum ada peringkat

- 12.4 Then and NowDokumen5 halaman12.4 Then and NowMarilu Velazquez MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- A Brief Notes On Contract Labour (R&A) ACT, 1970 & RULES: Composed byDokumen12 halamanA Brief Notes On Contract Labour (R&A) ACT, 1970 & RULES: Composed byGabbar SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Racial Sexual Desires HalwaniDokumen18 halamanRacial Sexual Desires Halwaniww100% (1)

- Death Certificate FormDokumen3 halamanDeath Certificate FormMumtahina ZimeenBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Work ImmersionDokumen11 halamanWork ImmersionSherwin Jay BentazarBelum ada peringkat

- MBTI Personality Type Test: Name: - Roll NoDokumen4 halamanMBTI Personality Type Test: Name: - Roll NoSaurabh Kulkarni 23100% (1)

- Behavioural Competency Assessment and VerificationDokumen41 halamanBehavioural Competency Assessment and VerificationNelson ChirinosBelum ada peringkat

- TransferapplicationDokumen17 halamanTransferapplicationsandeeparora007.com6204Belum ada peringkat

- Unpeeling The Onion: Language Planning and Policy and The ELT ProfessionalDokumen27 halamanUnpeeling The Onion: Language Planning and Policy and The ELT ProfessionalFerdinand BulusanBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Final ISO IEC FDIS 17065 2012 E Conformity AssDokumen77 halamanFinal ISO IEC FDIS 17065 2012 E Conformity AssahmadBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)