Rural Income Analysis in Nigeria

Diunggah oleh

YaronBabaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Rural Income Analysis in Nigeria

Diunggah oleh

YaronBabaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Journal of African Studies and Development Vol. 2(4), pp. 99-108, May 2010 Available online http://www.academicjournlas.

org/JASD ISSN 2141 -2189 2010 Academic Journals

Full Length Research Paper

Determining rural farmers income: A rural Nigeria experience

R. A. Olawepo

Department of Geography, University of Ilorin, P. M. B. 1515, Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. E-mail: ralfabbey@yahoo.com.

Accepted 8 February, 2010

This paper describes the earning activities of farmers in Afon district, a rural area in Kwara State, Nigeria with a view to assess factors determining rural farmers income. 268 farmers were interviewed through questionnaire administration, and the results show that a large number of rural farmers depend on family labour, local inputs and personal instincts to earn productive incomes. The farmers income in this study is used as a major tool for the isolation of basic factors that ought to be accorded priority in subsequent rural development policy. The findings also show that through the use of stepwise multiple regressions, four factors were found to be the main determinants of a farmers income out of the twelve examined. These are x3(farm output/yield per ton), x4(cost of farm input and implements), x11(accessibility to credit facilities), and x8(transport cost). In all twelve cases examined four variables together account for about 84.09 % of the total variance in income of farmers within a given year. Appropriate policy recommendations are provided to improve farmers income nation wide. Key words: Income, rural, development, facilities, operators, small-scale, food-baskets. INTRODUCTION The majority of the rural populace in Nigeria either depends entirely on farming and farming activities for survival and generation of income, or depends on these activities to supplement their main sources of income. The validity of this statement becomes evident when it is realized that over 90% of the countrys local food production comes from farms, which are usually not more than 10 ha in size, with at least 60% of the population earn their living from these small farms. The World Bank (1997) described rural farmers in Nigeria as small scale operators, tenants or landless, characterized by low income and high nutritional deficiency. They also have limited assets, large family size and high dependency rates. Despite their situation, these rural farmers and their farms collectively form an important foundation on which the nation economy revolves. The significance of rural farming can thus, not be over emphasized as rural areas form the food basket of the nation, and a major source of export materials. The fortunes of poor rural farmers can be determined by a number of factors. The initial distribution of income accruing to the rural farmer stands out as the most accessible determinant of the rural standard of living, since it is most quantifiable factor and the most reliable as majority of the people in the rural areas are predominantly farmers. Territorial social indicators provide a means of measuring the extent to which various human needs are met. The determinants of income among the target population therefore serve as social indicators of their standard of living. Adedayo, (1985) suggested that the income levels of rural communities may be attributed to certain crucial factors, and understanding these factors may hold the keys to effective rural development policy making. This in part led to the submission of Olatona (2007), that a closer look at the determinants of rural income provides an indepth knowledge into the factors that explain low income yields and poverty in rural regions where these rural farmers constitute about 90% of the total population (Olayemi, 2001; Olatona, 2007). Adedayo (1985: 25) has also suggested that any rural development policy aimed at poverty alleviation should concentrate on farming, which is the main occupation of the poor, who lack access to credit, farm input and implements and are unable to save or own production infrastructure. It is worthy of note that elimination of poverty, though always an aim of development assistance, has been brought more sharply into focus in the Nigerias development policies. For such communities of farmers, there is now a fresh emphasis on delivering outputs which have

100

J. Afr. Stud. Dev.

verifiable impacts in their standard of living. There is therefore the need to investigate more on those aspects that affect their incomes positively. The inventorization of farmers income in Nigeria has always been problematic. This is because most of the rural farmers do not keep records and a host of them are not literate. Meanwhile, the Federal and State Governments have been trying to alleviate farmers problems the rough various programmes. Despite all these development efforts, the rural farmer is still regarded as poor. The basic questions still remain: what is the average income of the rural farmer? What is the production level of the rural farmers in the study area? Are there some notable factors that can be isolated as determining the rural farmers income? These and other questions would be the bases of this study. The aim of this study therefore is to assess rural farmers production, income and, to examine the varied factors that determine income differentiation among the rural farmers in the study area. The agricultural sector is the largest sector of the States economy, employing over 70% of the adult labour force. The sector impacts on many aspects of development in the state. Apart from striving to meet the food needs of the citizenry, the agricultural sector impacts strongly on the needs of the people, the states Industrialization efforts, particularly agro-industrial sector and the over all quality of life of the people. At the same time, agricultural production and productivity depend largely on the quality of land and sustainable practices. Consequently, there is a need to make agriculture economically viable by seeking a balance between efficient and productive agricultural enterprise and environmental protection and sustainability (Olawepo, 2003). Afon district in Kwara State, Nigeria has a large potential of agricultural resources and it is one of the main food baskets of the state. This study has afforded the author the opportunity to obtain first hand information on the structure of production among these set of rural farmers. The study area is also characterized with some relative problems which are typical of a Nigerian rural setting. The rural farmers here are saddled with problems associated with income generation and their access to fund, land policy issue, transportation problems and a host of others. The farmers income in this study is used as a major tool for the isolation of basic factors that ought to be accorded priority in subsequent rural development policy. This will also help in the realization of government efforts to improve rural production vis--vis rural income generation in the State in general. The traditional way of monitoring the economic situation in agriculture has been by means of indicators of factor or reward (Olatona, 2007). These can relate to all the fixed factors (land, labour, capital) irrespective of who owns them. Olayemi, (2001) opined that this could be done by deducting charges of hired labour, borrowed capital, and rented land, only those factor rewards belonging to the farmer and other family labour are revealed. This residual is often taken to be the income

accruing to farmers and the unpaid members of their households for working in agriculture and using their land and capital in the industry. However, households that operate farms often receive, in addition to their rewards from farming income from running non farming businesses. The study area The Study area is Afon District in Asa Local Government Area, near Ilorin in Kwara State, Nigeria. Asa is one of the sixteen Local Government Areas in Kwara State, located in the south western part of the state. Afon the headquarters is about twenty seven kilometers from Ilorin, the state capital. Afon district is about 1,525 sq km with a population of over 26,800 farming families by 2007 estimate (IADP, 2007). It is often estimated that Asa Local Government Area has one of the largest number of rural settlements in the state and most of them are domiciled farmers. The area stretches from the peri-urban fringes of Ilorin city to the northern boundary of Oyo State. It also shares boundary with Oyun Local Government Area in the eastern part and Moro Local Government Area towards the North (Figure 1). Most inhabitants in the area are predominantly farmers and are involved in small scale/subsistence agriculture. This is especially true for the men while petty trading, pottery, weaving and assistance on farms are common among the women. A small proportion of the women are also involved in market gardening and commercial agriculture especially in the production of sheer butter resources and locust bean processing, to service mainly the capital city, Ilorin and the neighbouring communities. Crops like yam, cassava, maize corn and few tree crops like coffee and kola nuts are grown in the southern fringe of the Local Government Area. Afon district is characterized by tropical wet and dry sea-sons, with a monthly average temperature of about 29 C. The month of March has the highest monthly average temperature of about 32 C while the annual average rainfall record is estimated between 1200 and 1400 mm (Ajibade, 2002: 1). The major River in the area is Asa River which supplies the largest proportion of portable water to the whole area and Ilorin community. There are also some popular markets in the area; they include those of Afon, Odo-Ode, Ogbondorko, Oniyere and Aboto-oja to mention a few.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Ten of the settlements in the study area were randomly selected for this study. This was done by zoning the communities into five on the basis of wards, and two settlements were randomly chosen from each ward. A minimum of 10% of the farming family were chosen, using the rural household heads as our sampling unit. This method has been variously used and suggested by authors in similar studies. For example Tunde (2005) and Fatulu (2007) used a minimum of 10% of farming families in researches involving rural

Olawepo

101

Figure 1. A map of Afon district, Asa local government area, Kwara state, Nigeria. Source: Kwara state ministry of lands and housing, 2007.

farmers. Similarly, Ogunsanya (1983) in an earlier study on rural food production suggested a minimum of 10% rural household heads on studies involving rural residents. At the end of the selection exercises, two hundred and sixty eight (268) farmers were interviewed accordingly through structured questionnaires. These questionnaires were pre tested through a pilot survey in Odo-ode, (one of the smallest communities) to examine the views of farmers on key issues. These were later incorporated in the final draft eventually used. The questionnaires raised questions relating to farmers income, accessibility to credits, production methods, farm inputs as well questions relating to farm potentials and problems. These afforded the researcher some repeated journeys to the district during the third quarters of 2008. The data collected were analyzed through the use of descriptive statistics using percentages and cross tabulation as means of explaining the outcomes of findings. Lorenz curve was constructed to explain the distribution of income spread and levels of inequality among farmers in the study area. The Stepwise Multiple Regression Analysis was also adopted in the analysis of data collected to measure and identify the strength of the factors determining income differentiation from farming production within a farming season. The Stepwise Multiple Regression model affords a well structured linear combination of the various factors affecting income differentials. These variables were chosen based on past studies in similar

interactions relating to farmers income. In this wise, the Dependent variable is the wealth index of farmers (Median income from farming production in a farming season) while twelve variables were selected as the independent variables. Our regression equation would thus be: Y= a+b1x1+b2x2+b3x3bnxn +e Where Y is the family are the factors that constant, and e is the regression coefficients dent variables are: wealth index from farm production, x1.xn determine income differential, a being a standard error respectively and b1----bn are while a is constant. These twelve indepen-

X1 = types of crops and crop variety. X2 = farm size in terms of plots and farm stock. X3 = farm output/yield (in tons). X4 = costs of farm inputs and equipment), X5 = family size. X6 = sales from previous agricultural year. X7 = savings from previous agricultural year. X8 = Transport cost/distance to market. X9 = climatic factor/on set of rain. X10 = farming system employed.

102

J. Afr. Stud. Dev.

X11 = accessibility to credit facilities. X12 = other non farm incomes. A lot of problems were encountered during the collection and collation of data during our field trips and visitation to the study area. Some of these problems serve as limitation to the validity of these discussions. However, efforts were made to make the data more reliable and free of biases. The human nature of the data required constituted major problems, some respondents saw some enquiries about their income and social conditions as invasions of privacy. Rural residents are usually suspicious when it comes to asking questions in this part of the country. However, we secured the cooperation of the community leaders in various communities and this helped us to generate very reliable data at the long run.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION This section deals with analysis of data collated from the field work. The major task of this section is to explain farm production and income in the study area. For the purpose of discussion it is divided into four major sections; these are general characteristics of respondents, farm production and marketing of farm resources, wealth index and farm incomes, and the determinants of farmers income in the study area. Table 1 General characteristics of respondents The main effort here is to assess farmers personal information and questions were exclusively asked regarding their sex, ages, family sizes and educational qualifications. Farming is being under-taken by men and women in the study area. While the men prune and till the ground for continuous production women deal with harvesting, processing and marketing of sheer butter production in the study area especially in the core area of Afon district and the neighboring communities. It is clear that the majority of people dealing with farming in the study area are mostly men. About 73.5% of our respondents are men while only 26.5% are their female counterparts. It was however revealed that majority of women farmers here are involved in the picking of sheer butter nut, washing, cooking and actual marketing of the products in the various markets, some of them however do actual farming through hired labour and engagement of itinerant farmers/labourers. As regards the age of our respondents, it is evident that a large proportion of our respondents fall within the age range of 26 - 45, that is about 64.54% of the total num-ber of local farmers involved in farming production. From these findings, inference can be made that the active population makes up the main farming labour force in the study area. The younger age range of 16 - 25 has a lower percentage of about 8.95; this indicates that farming is exclusive job for the elderly, especially the men folks. This is evidently shown by the number of people found in the age bracket 55 and above. This group accounts for about 6.71% of the total labour force.

The issue of family size generally is important in every aspect of farming production this is because it affects the labour force as well as per capital output. Like many farming production, the processing of sheer butter resources is a family labour that involves the parents and the children. These include the numbers of wives, children, dependants and other relations from outside and those living under the same roof. This study also revealed that majority of the respondents have large family sizes especially those in Afon, Laduba and Ogbondoroko. About 36.57 of the respondents have a family of 11 people and above, while 23.13, 13.18 and 11.57% have family sizes of between 79, 5 7 and 3 - 5 respectively. This implies that there are many more mouths to feed and far farming is the major occupation of people in this part of the country, many more people would be involved in farming activities especially in sheer butter production businesses. It has been known from past studies that the level of education has an exponential relationship with the farmers level of susceptibility to the adoption of innovations and modern farming techniques. For example, Agboola (1997) confirmed this in related study in some parts of South west Nigeria. Majority of the farmers in this study (about 56.72%) do not have formal education. No wonder the do it alone attitude of theirs is difficult to discard from their mind. This discretely affects their methods of production as well as acceptability of new information and farm productivity. Farming productivity and market development Farming practices Farming activities in the study area are for both subsistence and commercial levels. It could be observed that the system of mixed cropping is widely practiced. Apart from sheer butter cropping, farmers are involved in the production of tubers, grain production and some root crops. Table 2 indicates that about 52.24% of them are involved in commercial farming, 22.01% are producing at subsistence level, 21.27% are involved in plantation production while 0.75% are itinerant farmers or labourer/farmers. As regards types of crops grown in the area, about 25.74% are producing root crops, in conjunction with sheer butter production, and 22.38% grew grains and legumes. Similarly about 8.58% are involved in vegetables production, while 43.28% plant all the four types of, crops within an agricultural year. A break down of this is shown on Table 3. At times these farming systems are produced on full time, while in other times they are to supplement their income. Table 4 on the other hand shows the farm out put accruing from farming production. Generally it shows a low out put per ton for all farmers in the area. About 23.88% of the farmers produced less than 1

Olawepo

103

Table 1. Age characteristics of respondents.

Age 16-25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56 and above Total

Ogbondoroko 3 10 18 7 0 38

Laduba 5 22 9 10 4 50

Afon 9 14 22 18 7 70

Odoode 0 2 4 2 0 8

IlaOja 1 1 2 0 0 4

Okeso 0 1 5 2 0 8

Gbagba 1 1 2 1 1 6

Budo Egba 2 20 28 10 4 64

Olomoda 1 1 3 2 1 8

Oniyere 2 4 4 1 1 12

Total 24 76 97 53 18 268

% 8.95 28.35 36.19 19.77 6.71 100

Source: Field work, 2008.

Table 2. Farming systems.

Farming system Subsistence Commercial Planta Tion Itinerant Total

Ogbondoroko 8 20 10 0 38

Laduba 10 22 11 7 50

Afon 20 32 15 3 70

Odoode 1 4 3 0 8

Ila oja 1 3 0 0 4

Okeso 2 4 2 0 8

Gbagba 0 5 0 1 6

Budo egba 10 43 10 1 64

Olomoda 3 3 2 0 8

Oniyere 4 4 4 0 12

Total 59 140 57 12 268

% 22.01 52.24 21.27 4.47 100

Source: Field work, 2008.

Table 3. Types of crops grown.

Crops Root crops Grains and legumes Vegetables All Total

Source: Field work 2008.

Ogbondoroko 10 8 2 18 38

Laduba 12 18 1 19 50

Afon 18 17 5 30 70

Odo Ode 1 1 0 6 8

Ila oja 1 1 0 2 4

Okeso 1 1 2 4 8

Gba gba 1 1 1 3 6

Budo egba 22 10 8 24 64

Olomoda 1 0 1 6 8

Oniyere 2 3 3 4 12

Total 69 60 23 116 268

% 25.74 22.38 8.58 43.28 100

tonne of farm produce in a farming year, 18.65% produces between 1 - 2, while about 16.79 and 23.13% produced between 2 - 3 and 3 4 tonnes

respectively. A small proportion of farmers (4.85%) however produce above 5 tonnes given the prevailing conditions in the study area. The highest

producers are found around Budoegba and Afon communities. The low farming output could be attributed to the low prices of farm resources, poor

104

J. Afr. Stud. Dev.

Table 4. Farm out put in tonnes.

Output per tonnes 0-1 1-2 2-3 3-4 4-5 Above 5 Total Source: Field work 2008.

Ogbondoroko 10 8 7 6 4 3 38

Laduba 15 16 10 4 4 1 50

Afon 12 8 13 29 2 6 70

Odo-Ode 5 2 1 0 0 0 8

Ila oja 2 1 0 1 0 0 4

Okeso 3 4 0 1 0 0 8

Gba gba 1 0 4 0 0 1 6

Budo egba 9 1 8 20 24 2 64

Olomoda 3 4 1 0 0 0 8

Oniyere 4 6 1 1 0 0 12

Total 64 50 45 62 34 13 268

% 23.88 18.65 16.79 23.13 12.68 4.85 100

Table 5. Sources of capital.

Sources Personal Family/Friends Banks Cooperatives Total

Ogbondoroko 30 0 0 8 38

Laduba 38 2 0 10 50

Afon 55 3 2 10 70

Odo Ode 8 0 0 0 8

Ila oja 4 0 0 0 4

Okeso 8 0 0 0 8

Gba gba 4 0 1 1 6

Budo egba 49 5 1 9 64

Olomoda 6 2 0 0 8

Oniyere 1 9 1 1 12

Total 203 21 5 39 268

% 75.74 7.83 1.86 14.55 100

Source: Field work 2008.

accessibility to credit facilities, high transport cost and poor rain in the preceding year. Marketing of farm productions The important role played by markets in the economic life of any rural community cannot be over stressed. Apart from the collection and bulking of local products, they also distribute foodstuffs and control cash flow in the economy. The existing markets were at Afon, Aboto, Ogbondoroko. Large quantities are also carried to Ilorin, Offa and some parts of Oyo state by middlemen and whole sale vendors. For all the farm products studied, observation revealed that wholesale markets and

public retail mixes expanded haphazardly into surrounding villages, especially in and around Afon, Laduba, Oniyere, Ganmo, Ote and Budo Egba. It was also observed that there is a farming market at Amoyo, Gbagba and Afon has remained an important sheer butter market attracting traders from Ilorin, Ogbomosho, Ajasse, Offa and , Gambari in Oyo State. Apart from this, another market was built at Idi-ose and it attracts traders from Oyo, Igboho and other places from the Western parts of the country. It was also revealed that public markets, neighbourhood stores and street vendors were found to be the most important outlet for retail grain and tuber products. These are through Afon, Buduegba, Ogbondoroko and laduba. Commodities are

usually transported to centres and Lorries. It can be deduced that neighbourhood retail tent, street hawkers and retailers became important elements in the retail mix of food stuff and other related commodities studied, because of the consumers' need for locational convenience. Capital formation and farmers income Most farmers in this sector started their production with low capital formation. From the findings, a large proportion of farmers here had their capital base from personal finance and savings from family income. Table 5 shows that about 75.74. 1% of the farmers sourced their capital from

Olawepo

105

Table 6. Average income from farming production.

Income N 1-10,000 10,000-20,000 21,000-30,000 31000-40,000 40000-50,000 Above 50,000 Total

Ogbondoroko 2 3 5 18 6 4 38

Laduba 1 2 3 14 28 2 50

Afon 13 6 15 11 13 12 70

Odo Ode 1 5 1 1 0 0 8

Ila oja 4 0 0 0 0 0 4

Okeso 2 3 2 0 0 1 8

Gba Gba 1 3 0 0 0 2 6

Budo egba 2 10 4 8 24 16 64

Olomoda 4 2 1 1 0 0 8

Oniyere 2 4 3 3 0 0 12

Total 32 38 34 56 71 37 268

% 11.94 14.17 12.68 20.89 26.49 13.80 100

Source :Field work 2008.

personal savings, 7.83% obtained their capital from families and friends, while a small proportion (1.86%) had access to credit facili-ties from banks. Similarly, 14.55% sourced their capital from few available cooperative societies in their local environment. This form of shallow capital base and poor accessibility to funding probably accounts for small scale holdings. The few people that had access to bank loans are from Afon and the neighbouring villages where there are Commercial banks and Micro finance or Community banks. This may also be as a result of lack of colaterals or as a result of high rates of interest. In order to assess the level of incomes, the gross sales from previous agricultural years and farmers income by settlement were collated. Table 6 shows the average income of the producers based on the sale from the previous agricultural year. Income generally is low from agricultural production as a result of low capital input into production, low level of education, low price level of farm produce, and poor accessibility to credit facilities among others. From Table 6, it is observed that income level rises rapidly from low income of N1 - 1000 until income of between N40,000 - 50,000 when it descends again. Within

an agricultural year as observed, 11.94% of our respondents earned between N1 - 10,000, 14.17% earned between N10,000 - N20,000, while only 13.80% earned above N50,000 per annum. When considered in the context of average National per capita income,this is virtually low. Similarly Table 6 shows the estimate of average income per settlement in an agricultural year based on the sale from the previous year among our 268 respondents. From this distribution it is possible to infer on the level of income generally in the study area. This is generally low when compared to the standard poverty line of 1 dollar per day. This might also be as a result of the circular flow of poverty among farmers. Despite the spread of low income from farming activities, it was evident that there is a great in-equality in the distribution of farm income. The Lorenz curve in Figure 2 shows a depiction of in-equality among farmers in the study area. For instance it shows that the lower half of the population receives only about 21% of the total income; conversely, half the income goes to only 32% of the population. Similarly about 90% of the population earns 62% of the total income. The in-equality gap curve is farther away from the equality line in most part of

the graph until the high income level is reached. This is characteristically of the poverty nature among rural farmers and the general vicious circle among local farmers throughout the country. Determinants farmers of farming income among

Having discussed fully on the production of farmers within a farming season and Incomes accruing to the different categories of the producers, efforts were made by the researcher to assess the factors that determine the incomes of farmers in the study area. Twelve variables were selected as determinants of variation in income as earlier discussed. A stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out. The dependent variable (y) is the wealth index using average family income within a farming season while variables x1 - x12 are the independent variables. The multiple regressions on Table 10 suggest several findings. In all 12 cases, 4 of the variables were found to be significant at the specified tolerant level of 0.50 entries into the model. These are x3 (farm output/ yield per ton), 4 (costs of inputs and equipment), 11 (accessibility to credit facilities), and

106

J. Afr. Stud. Dev.

120 100 80 60 40 20 0 1 y x

10 2 20 3 30 4 40 5 50 6 60 7 70 8 80 9 90 10 100

Figure 2. Lorenz curve showing distribution of farmers income.

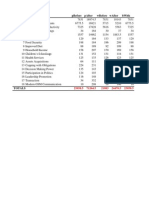

Table 7. Multiple regression output.

Variables Intercepts X3 X4 X11 X8

Parameter Estimates 1.1310 2.0680 9.6890 0.7820 0.9660

Standard Error 2.505 0.9030 0.9520 0.4880 0.1620

R 0.8482 0.8902 0.9080 0.9170

r2 0. 7196 0.7925 0.8245 0.8409

Co efficient of determination 71.96 79.25 82.45 84.09

% of contribution 71.96 7.29 3.20 1.64

Cumulative % 71.96 79.25 82.45 84.09

Source- computer output.

x8(transport cost) From the findings on Table 7, it is observed that x3 (farm output per yield) in a particular year is probably the best predictor or determinant of farming income. The correlation co-efficient of this variable is 0.7196 and co efficient determination of 71.96. This indicates that about 71.96% of the variance is associated with variation in the total income of a farmer within a farming season. This is evident in that farmers with high yield are also the higher income earners especially in Afon, Laduba, and Ogbondoroko among others. This is because the higher the farm yields the higher the income of farmers, all things being equal. This may however be affected by other market conditions and environmental factors. Such market factors may be the prevailing prices of commodities per ton and the market schedule within a specified period. The cost of inputs and equipment (x4) also appeared to be important determinant of income among farmer producers with a joint correlation of 0.8902 and co efficient determination of 7925. This also means

that only 7.29% variation of income is explained by this variable. It also means that about 79.29% of the joint variance in income determination is jointly explained by the two variables x3 and x4. One can thus infer that the higher the quantity of production and the less the net cost of input of produce, the higher the variation in income. Such cost of input may include the cost of hired labour, farm equipment and implements, cost of fertilizer and chemicals as well as cost paid on hired labour via the use of tractor for ploughing the land within the agricultural year. It was observed that farmers that had access to tractors from the Ilorin Agricultural Development Projects (IADP) had large hectares of land for cultivation at subsidized rate and thus enjoyed improved production. This was noticed mainly in Afon, Ogbondoroko and Laduba where IADP has farm support schemes. Similarly accessibility to credit facilities (x11) has also related well to the variation in farm income with a joint correlation of 0.9080 and a coefficient determination of

Olawepo

107

8245, and a joint contribution of 82.45% by the three variables. This indicates also that about 3.2% additional variation in total farm income is explained by accessibility to credit facilities. For example the few producers in Afon and Laduba that had access to credit facilities had enough resources to invest in farm tools, grounding machines and thus consequently had higher income. These were mainly obtained through co-operative Societies, Community Micro Finance bank at Afon and it was noticed that this gesture enabled them to have more land areas of land for cultivation. It could be inferred that access to credit facilities will afford farmers to invest more into farming business. For example, farmers would have more funds to expand their cultivation and divert to other farm production to enhance more profitability and hence more income will accrue. Transport cost (x8) however added about 1.64% to the total variation in income of farmers in the study area and thus serve as a very important predictor of farmers income. It was observed that cost of transportation from the farming villages to the markets is high in most of the rural communities. This is because road accessibility is poor and few transporters patronize the farming communities. This often resulted to high cost of transportation, spoilage of farm produce as well as negative attitudes of farmers to produce for market. In all, the four variables together account for about 84.09% of the total variance in income of farmers within a given year. The remaining variables are not significant in the determination of farmers income and probably their correlations are too low to offer any meaningful explanation in this study. This also means other variables besides the selected ones might be significant as well as non farming incomes. The explanatory regression equation can thus be written as Y = 1.130+2.0600x3 + 9.6890x4 + 0.7820x11 + 0.9660x8. RES = 84.09% This means when there are improvements in the output per yield, prices of farm equipment, accessibility to credit facilities and good transportation facilities with less cost, farmers well being and income will not only be stable but will increase significantly. Conclusion This study has exclusively examined the production of farm resources and how it has affected peoples income as a means of poverty alleviation. The main aim of this study is to access farmers production within a farming season and examine the factors that affect variation in their farm incomes. Results from this study indicate that farming in the study area is a lucrative business but production is hampered by poor credit facilities and the general vicious circle of poverty which has affected the farmers nega-

tively. Despite these, it has served as a very formidable means of poverty alleviation among the people of Asa Local Government area. A stepwise multiple regression analysis was carried out to assess factors that may explain the variation observed from farmers income in a farming season. Four factors were found to be the main determinants of a farmers income out of the twelve examined. These are x3 (farm output/yield per ton), x4 (cost of farm input and implements), x11 (accessibility to credit facilities), and x8 (transport cost). In all twelve cases examined four variables together account for about 84.09% of the total variance in income of farmers within a given year. This is common to most rural farmers in Nigeria where more than 85% of food productivity is based. When there are improvements relating to these factors, increased and sustainable productivity will be enhanced. This may be a panacea to improved productivity and enhanced agricultural development not only in the rural areas, but in general agricultural development nationwide. In order to have farming and agricultural resources meeting the financial need of the local farmers, the following recommendations are suggested. The government should encourage the development of local industries that will process farm resources in the rural areas; this will reduce the spoilage of farm produce. Similarly, government should have a sound policy that will make capital and credit facilities more accessible to the local producers. The focus of the policy would be to promote ecologically sound and profitable farming systems and adaptable rural development programmes targeted at small scale farmers. It would also be to increase agricultural production and productivity, enhance food security, increase earnings from agriculture and regenerate the environment in the overall context of sustainable agriculture. The development and formation of more cooperative societies among the people will also enhance increase income among the rural farmers.

REFERENCES Adedayo AF (1985). The implications of Community Leadership for Rural Development Planning in Nigeria, Comm. Dev. J., 20: 24-31 Ajibade LT (2002). A preliminary assessment of comparative study of Indigenous and Scientific Methods of Land Evaluation in Asa L.G.A. Kwara State, Geo-Studies Forum, 3(1-2): 1-7 Bolton JE (1971). Report of the Committee of Inquiry on Small Firms. HMSO, London Central Bank of Nigeria (2001). Report and Statement of Account For Nigeria, CBN, Lagos, Nigeria. Daniels L, Fisceha, (1992). Micro and Small Scale Enterprises in Botswana: Results of a Nationwide Survey Gemini Technical Report, No. 46, Washington DC, Development Alternatives Inc. Fatulu B (2007). Rural Women Participation in food Production, An Example from Kwara State, Nigeria, unpublished M.Sc Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. Federal Office of Statistics (2005). Statistical Report on Nigeria. Government Printers, Lagos. Ilorin Agric Development Programme (IADP) (2007) Farming Activities in Kwara State, Monograph, IADP, Ilorin. International Labour Organisation (2005). Poverty Eradication. ILO,

108

J. Afr. Stud. Dev.

Geneva Kwara State Government (1996) Statistical Year Book. Government Press, Ilorin Korten D (1995). Steps Towards People-Centred Development: Vision and Strategies, in Heyzer, N., Riker, J.V. and Quizon, A. B. (eds) Government NGO Relations in Asia: Prospects and Challenges for People-Centred Development Poverty in Nigeria Proceedings of the 1975 Annual Conference. IUP, Ibadan. Obadan MI (1996). Analytical Framework for Poverty Reduction: Issue of Economic Growth Versus Other Strategies. Proceedings of the 1996 Annual Conference of the Nigerian Economic Society. (Ibadan: NES). OECD, (2003). An Overview of major Policy Issues, Prentice Hall, Paris. Ogunsanya AA (1983) Constraints to food Production in Rural Kwara, Proceedings of Annual Conference of Nigeria Geographical Association, Ilorin.

Olatona MO (2007). Agricultural Production and Farmers Income in Afon District, Unpublished B.Sc Project, Department of Geography, University of Ilorin. J. Bus. Soc. Sci., 8(1-2): 32-39. Olawepo RA (2003) Managing the Nigerian Rural Environment through Participatory Rural Appraisal. Ilorin J. Bus. Social Sci., 8(1-2): 32-39. Olayemi JK (2001). A Survey of Approaches to Poverty Alleviation. A Paper Presented at NCEMA National Workshop on Integration of Poverty Alleviation Strategies into Plans and Programmes in Nigeria, Ibadan Tunde AM (2005). Gender Differences in Agricultural Production in Oke Ero L.G.A., Kwara State unpublished M.Sc Dissertation, Department of Geography, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. World Bank (1995). Advancing Social Development. Washington, D.C.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- Oppenheim-Questionnaire Design Interviewing and Attitude MeasurementDokumen305 halamanOppenheim-Questionnaire Design Interviewing and Attitude MeasurementYaronBaba100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Creative Brief - EsteeDokumen3 halamanCreative Brief - EsteeMohnish PanjabiBelum ada peringkat

- Mini Importation Guide 1.0Dokumen32 halamanMini Importation Guide 1.0tongsman100% (1)

- Cosntructing For InterviewDokumen240 halamanCosntructing For InterviewYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Hoverboard Marketing PlanDokumen39 halamanHoverboard Marketing PlanHannah PuntBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Consumer Behavior Assignment On WiproDokumen10 halamanConsumer Behavior Assignment On WiproHaris Naved Ahmed100% (1)

- Ice Cream Project - FinalDokumen22 halamanIce Cream Project - FinalAlhad Apte75% (4)

- The Benefits of Implementing Lean Management System at IKEA Malaysia CompanyDokumen12 halamanThe Benefits of Implementing Lean Management System at IKEA Malaysia Companydrustagi100% (1)

- Organizational Structure of The Coca Cola CompanyDokumen24 halamanOrganizational Structure of The Coca Cola CompanyPennyLiBelum ada peringkat

- Case Analysis - Jones BlairDokumen5 halamanCase Analysis - Jones BlairMaoBelum ada peringkat

- Notes On MVAT Act For StudentsDokumen23 halamanNotes On MVAT Act For StudentsDeepali SolankiBelum ada peringkat

- Indonesian Digital Mum Survey 2018-Presentation DeckDokumen34 halamanIndonesian Digital Mum Survey 2018-Presentation DeckAdiKangdraBelum ada peringkat

- No. Variables Pbefore Pafter Wbefore Wafter BwithDokumen2 halamanNo. Variables Pbefore Pafter Wbefore Wafter BwithYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Tranform Roat EdDokumen4 halamanTranform Roat EdYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Food Security Status in NigeriaDokumen16 halamanFood Security Status in NigeriaYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- A Price Transmission Testing FrameworkDokumen4 halamanA Price Transmission Testing FrameworkYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- OutputDokumen1 halamanOutputYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Out-Reach and Impact of TheDokumen5 halamanOut-Reach and Impact of TheYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- SR - No. Investmentinputs Noimpact (0) P Littleimpact (1) P Greatimpact (2) P Totalproduct (P) %Dokumen1 halamanSR - No. Investmentinputs Noimpact (0) P Littleimpact (1) P Greatimpact (2) P Totalproduct (P) %YaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Analyses of Out-Reach and Impact of The Micro Credit SchemeDokumen3 halamanAnalyses of Out-Reach and Impact of The Micro Credit SchemeYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Investments Capacity Pattern With Micro CreditDokumen2 halamanInvestments Capacity Pattern With Micro CreditYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Micro Credit Impact On InvestmentsDokumen2 halamanMicro Credit Impact On InvestmentsYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Adp 2013Dokumen19 halamanAdp 2013YaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Frontier Functions: Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) & Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)Dokumen45 halamanFrontier Functions: Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) & Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)YaronBaba100% (1)

- Questionnaire Management SurveyDokumen15 halamanQuestionnaire Management SurveyYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Database Design: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokumen3 halamanDatabase Design: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Table Template For State Report2013Dokumen19 halamanTable Template For State Report2013YaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Econometric Analysis UsingDokumen13 halamanUnderstanding Econometric Analysis UsingYaronBabaBelum ada peringkat

- DMartDokumen11 halamanDMartAshwin DholeBelum ada peringkat

- Pengaruh Store Atmosphere Terhadap Hedonic Shopping Value Dan Impulse Buying (Survei Pada Konsumen Hypermart Malang Town Square)Dokumen5 halamanPengaruh Store Atmosphere Terhadap Hedonic Shopping Value Dan Impulse Buying (Survei Pada Konsumen Hypermart Malang Town Square)andraBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing notes-SIMS PDFDokumen246 halamanMarketing notes-SIMS PDFAjay DhawalBelum ada peringkat

- Publication: DNA Money Journalist: Anoop Chugh Story Idea: OOH Medium in 2009 and 2010Dokumen15 halamanPublication: DNA Money Journalist: Anoop Chugh Story Idea: OOH Medium in 2009 and 2010nudetarzan1985Belum ada peringkat

- E - Commerce WordDokumen56 halamanE - Commerce WordMayukhi DebBelum ada peringkat

- Service DesignDokumen43 halamanService DesignJeff GopezBelum ada peringkat

- CVS Pharmacy FinalDokumen16 halamanCVS Pharmacy Finalnikhilkumarrao50% (4)

- Unit 5 Macro and Micro FactorsDokumen17 halamanUnit 5 Macro and Micro FactorsKoushalya ChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- E-Commerce & Its ClassificationDokumen11 halamanE-Commerce & Its ClassificationShakir IsmailBelum ada peringkat

- SynopsisDokumen10 halamanSynopsisMuhammed AshfaqBelum ada peringkat

- 12 TRACENET-Organic - Traceablity System - SudhanshuDokumen51 halaman12 TRACENET-Organic - Traceablity System - Sudhanshugmswga2012Belum ada peringkat

- Save Your Small BusinessDokumen340 halamanSave Your Small BusinessNagy ZsoltBelum ada peringkat

- Winter ReportDokumen80 halamanWinter Report9824527222Belum ada peringkat

- Aldi and LidlDokumen18 halamanAldi and LidlchacBelum ada peringkat

- Singapore Property Weekly Issue 263Dokumen15 halamanSingapore Property Weekly Issue 263Propwise.sgBelum ada peringkat

- HLC LAS FORMAT AmitDokumen19 halamanHLC LAS FORMAT AmitAbhishek KesarwaniBelum ada peringkat

- Servicing of A Watch Includes The Complete Overhaul As Well AsDokumen1 halamanServicing of A Watch Includes The Complete Overhaul As Well AsRahul GuptaBelum ada peringkat

- Point-Of-Purchase Displays in The FMCG Sector: A Retailer PerspectiveDokumen9 halamanPoint-Of-Purchase Displays in The FMCG Sector: A Retailer PerspectiveNandani SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Marketing of MilkDokumen10 halamanMarketing of Milkpapai96Belum ada peringkat

- SAP MM Consignment: Create Consignment Purchase OrderDokumen1 halamanSAP MM Consignment: Create Consignment Purchase OrderVijay Kumar GBelum ada peringkat