Caciquismo - Definition

Diunggah oleh

ksteg12Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Caciquismo - Definition

Diunggah oleh

ksteg12Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

CACIQUISMO

From "Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture"

In general speech, the term cacique is applied to any individual who exercises power over others in a despotic and arbitrary fashion. Caciquismo indicates the dominion established by this type of leaderthe exercise of a real power through illegal coercion and the appointment and manipulation of formal authorities. Such control is carried out in an extralegal fashion, based on the control of the most important strategic resources (political, economic, and cultural) and through frequent recourse to physical force. English-speaking authors have debated the specificity of the term cacique and the usefulness of employing it to indicate something more than a jefe poltico local (local political boss). Even though some authors have used both terms without making a distinction, the prevailing opinion has been that caciquismo refers to a specific type of political activity. The detailed treatment of caciquismo in sociological literature has emphasized its most important characteristics. Pablo Gonzlez Casanova has insisted that this form of authoritarianism implies total control over wealth, honor, public office, and political power. Moreover, the cacique is both owner and master of his territory and the life and destiny of its inhabitants. He has more power in his region than any other more formally established political organization. In a similar fashion, Paul Friedrich defined the cacique as a strong and autocratic leader in regional and local politics whose power to command, characteristically informal, individualist and frequently arbitrary, is backed up by a nucleus of family members, fighters and dependents, and is particularly characterized by the use of threats and the exercise of violence. To these characteristics Antonio Ugalde has added political control over a geographical area and the potential use of violence, the recognition and legitimacy established on the axis between accord with his authority and the support of external political leaders. Luisa Par gave the term caciquismo to a form of political control in rural areas typical of a period when capitalism is penetrating noncapitalist modes of production. According to Par, during such a time traditional authority based on a representation of collective interests within a community tends to disappear in favor of an individual or group of individuals who act as the main agents for capitalist penetration in a given community. Recent literature on local politics and caciquismo has insisted on its role as a form of political intermediation which has enormous relevance in the process of the creation of the Mexican state.

The History of Caciquismo

The term cacique is derived from kassicuan, a word in Arawak (the language of an indigenous Caribbean people) meaning to have or keep a house. The first recorded use of the term comes from the diary of Christopher Columbus, who heard it after his disembarking in Hispaniola, when it was used to describe the chief or lord of the indigenous Tanos people with whom he dealt. The Spanish conquistadors employed the term cacique to indigenous leaders and cacicazgo to aboriginal chieftainships. During the colonial period, cacicazgo consisted in the Spanish Crowns recognition of certain indigenous titles and privileges as well as particular rights and obligations that were assigned to those Indian leaders who were identified as belonging to the aboriginal nobility. This investiture was rather more formal than actual, eventually becoming an institution of indirect government, a means of mediating between conquerors and conquered. In Spain, the term cacicazgo, apart from referring to the chieftainship of an indigenous village or people, is also applied to the excessive use of influence in public affairs. In this sense it becomes a label for extralegal means of control of electoral results based on influence and pressure exercised by strongmen backed by state administrative apparatuses at the local level. This political institution predominated in rural Spain during the first third of the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century in relation to living conditions in the country. In Independent Mexico, which sought to foster a direct, unmediated relationship between the citizen and the state, colonial cacicazgo was destroyed by liberal anti-corporatism, which sought to foster a direct, unmediated relationship between the citizen and the state. The term survived nevertheless, but identified with the exercise of a personal, autocratic leadership that was locally powerful but held a monopoly on links with the outside world, particularly with regard to public authority. During the last third of the nineteenth century, both the erosion of local government and the institution of political bosses during the Porfiriato led to order on a local level depending on authorities nominated from Mexico City who seemed tyrannical, despotic, and arbitrary to the local inhabitants. The terms cacique, cacicazgo, and caciquismo all reappeared in this context. Thus a large percentage of the local rebellions that led to the Revolution of 1910 originated to combat the tyranny of the caciques. During the Revolution, bandits and rebels first obtained local political control. In the process they too became regional caciques, thereby freeing themselves from the control of the central authorities.

Caciquismo in Modern Mexican History

The role of the regional caciques that emerged from the Revolution was decisive in the formation of the post-Revolutionary Mexican state. The way in which the activities of these regional leaders linked with the process of state consolidation has been a

Mexican state. The way in which the activities of these regional leaders linked with the process of state consolidation has been a constant theme in the studies on Mexican history and politics. The most important regional leaders included individuals such as Dmasco Crdenas, Primo Tapia, and Francisco Mgica in Michoacn; Adalberto Tejeda and Cndido Aguilar in Veracruz; Toms Garrido Canabal in Tabasco; Saturnino Cedillo and Gonzalo Santos in San Luis Potos; Felipe Carillo Puerto in the Yucatn; the Figueroa clan in Guerrero; and Jos Guadalupe Zuno in Jalisco. Many of these leaders came to power in regions that had no large or spontaneous campesino (peasant) revolts during the Revolutionary conflict. The campesino mobilization in favor of agrarian distribution benefited from an important ingredient: external organization that needed the formation of nuclei of intermediaries with extra-regional contacts. Here the role of the local caciques proved decisive. Minor local caciques developed in direct relation with regional leaders, basing their local political control on their ties to hierarchical systems of patronage. The best documented case is that of Carrillo Puerto in the Yucatn. However, studies on caciquismo and regional power in Michoacn also clearly illustrate this phenomenon. Cases such as that of the Prado family in La Caada de los Once Pueblos, the Ruiz brothers in Taretan, Martnez and Zavala Cisneros in the north-central area, or Dmaso Crdenas in La Cinaga de Chapala are relevant. The participation of these local strongmen was decisive in the initial stages of the construction of the post-Revolutionary Mexican state. Even though rural areas were the privileged locus of action, their role in the cities also has been relevant. The later growth of the state political and administrative apparatus led to conflict with and, to a large extent, the dissolution of these cacicazgos. The centralist political organization severely limited the autonomous bases of the regional caciques to the point that it destroyed their sources of independent power, the availability of armed forces, and their privileged access to state resources. At the same time their guarantees of security and the satisfaction of material necessities mediated by the caciques became tied to the control and dependency of their clientele in relation to the state. Although in many cases the process made the presence of the cacique unnecessary, it institutionalized mediation as a means to exchange support for guarantees and benefits that favored the state. In this sense the caciques were a fundamental element in the establishment of the client-based character of the Mexican political system.

Caciquismo and Political Intermediation

The role of caciquismo as a means of intermediation has been emphasized from various analytical points of view. Luisa Par sees caciquismo as a phenomenon of intermediation apparent where there are situations in which links are to be made between different means of production. In this context it is the requisite mechanism for the implanting of capitalism in a non-capitalist environment. Historically this process occurred with multiple regional variations. Nevertheless in general it is presented as a structuring process for local power whereby popular leaders personally benefit from the strong support of their followers by mediating their demands. Through this process they become caciques. The centralist political apparatus favored this transition, once the pressures of the system had largely been eased by the co-option and corruption of the local leaders, before attending to the demands of the group these caciques represented. This cooptation favored the economic aspect of the mediation. The cacique generally made a profit from the introduction of progress and modernity, along with goods and services introduced into his areas of control. At the same time he appropriated resources removed by diverse means from the people under his rule. These activities included the direct exploitation of campesinos and jornaleros, various forms of usury, illegitimate use of community possessions, the exploitation of labor on a community and cooperative basis, as well as speculation and corruption. These activities required political control to bring to fruition. Thus, though the interest of the cacique was the maintenance of control outside the economic field, political interests came first on many occasions. From this perspective, the cacique as intermediary in a process of control mixes in the political advantages that he needs to obtain economic benefits. Hence the caciques intermediary position is of equal relevance in both political and economic spheres. The cacique is thus placed in two distinct realities and takes advantage of his skills and structural position to make connections. In Eric Wolfs terminology, a cacique in his role as political intermediary protects the links or points of communication that connect the local system with a wider society. The economic role of the institution is less relevant in this case. Most important is that the intermediary acts as a connecting link between different levels of contact. If these levels are defined in terms of power differences, one must analyze how they are exercised. The intermediary is looking for power on two levels; he manipulates the control he has on one to strengthen his position with regard to the other. Thus the control he holds in each sphere depends on the success with which he maintains control over the other. Following this line of argument, Guillermo de la Pea has proposed that caciquismo should be understood within the context of the relationship between the dual process of the creation of the state and the creation of the nation. He states that given that the project of consolidation on a state level demands the disappearance of alternative powers within its territory, the state makes use of political intermediaries to generate or increase the dependency of individuals who manifest a degree of independence. On the other hand, the process of national consolidation brings with it the establishment of a symbolic universe of connections that are generally accepted and shared by all members of the nation. This implies an important transculturation of those segments of the population that have to unify the nation, which frequently forces a redefinition and reorganization of these connecting levels. The intermediaries create the points of connection between their base sector and the rest of society, aiming to assure a specific behavior pattern from the population in particular areas, in exchange for expected benefits. Caciques play an important part in this process since they maintain their own activities and obtain personal benefits through obligatory monopolies on certain channels of access. See also Caudillismo

See also Caudillismo

Select Bibliography Bartra, Roger, et al., Caciquismo y poder poltico en el Mxico Rural. 8th edition, Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 1986. Brading, David, editor, Caudillo and Peasant in the Mexican Revolution. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980. de la Pea, Guillermo, Poder local, poder regional: perspectivas socio-antropolgicas. In Poder local, poder regional, edited by Padua, Jorge and Vanneph, Alain. Mexico City: Colegio de Mxico-CEMCA, 1986. Friedrich, Paul, The Legitimacy of a Cacique. In Local-Level Politics: Social and Cultural Perspectives, edited by Swartz, Marc J.. Chicago: Aldine, 1968. Kern, Robert, editor, The Caciques: Oligarchical Politics and the System of Caciquismo in the Luso-Hispanic World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1973. Martinez Assad, Carlos, editor, Estadistas, caciques y caudillos. Mexico City: UNAM-IIS, 1988. Salmern Castro, Fernando I., Caciques: Una revisin terica sobre el control poltico local. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Polticas y Sociales 30 (1984).

FERNANDO I. SALMERN CASTRO

Copyright 1997 by FITZROY DEARBORN PUBLISHERS

Persistent URL to this entry: http://www.credoreference.com/entry/routmex/caciquismo

APA CACIQUISMO. (1998). In Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture. Retrieved from http://www.credoreference.com/entry/routmex/caciquismo

Chicago Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, s.v. "CACIQUISMO," accessed June 27, 2013, http://www.credoreference.com/entry/routmex/caciquismo

Harvard CACIQUISMO 1998, in Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture, Routledge, London, United Kingdom, viewed 27 June 2013, <from http://www.credoreference.com/entry/routmex/caciquismo>

MLA "CACIQUISMO." Encyclopedia of Mexico: History, Society & Culture. London: Routledge, 1998. Credo Reference. Web. 27 June 2013.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Adobe Photoshop 9 Cs2 Serial + Activation Number & Autorization Code ADokumen1 halamanAdobe Photoshop 9 Cs2 Serial + Activation Number & Autorization Code ARd Fgt36% (22)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Household Budget Worksheet - Track Income & ExpensesDokumen1 halamanHousehold Budget Worksheet - Track Income & ExpensesJohn GoodenBelum ada peringkat

- 5003790-A ViroSeq v3 SW Manual USDokumen60 halaman5003790-A ViroSeq v3 SW Manual USksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Airfix 2011 CatalogueDokumen132 halamanAirfix 2011 CatalogueGordon Sorensen0% (1)

- Zaranda Finlay 684 Manual Parts CatalogDokumen405 halamanZaranda Finlay 684 Manual Parts CatalogRicky Vil100% (2)

- 132KV Siemens Breaker DrawingDokumen13 halaman132KV Siemens Breaker DrawingAnil100% (1)

- Self-Organizing Networks 26.06.2012Dokumen402 halamanSelf-Organizing Networks 26.06.2012ksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Mining Trends in The New World - GarnerDokumen89 halamanMining Trends in The New World - Garnerksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)Dokumen935 halamanVuk Stefanovic Karadzic: Srpski Rjecnik (1898)krca100% (2)

- New Evidence On The Relationship Between Democracy and Economic GrowthDokumen25 halamanNew Evidence On The Relationship Between Democracy and Economic Growthksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Good Governance, Institutions and Economic DevelopmentDokumen35 halamanGood Governance, Institutions and Economic Developmentksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Guide 6082 en PDFDokumen11 halamanGuide 6082 en PDFksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- Fiscal Policy Cycles and Public Expenditure in Developing CountriesDokumen17 halamanFiscal Policy Cycles and Public Expenditure in Developing Countriesksteg12Belum ada peringkat

- $$TR Sas 114 AllDokumen384 halaman$$TR Sas 114 Allctudose4282Belum ada peringkat

- Transmission Line ProtectionDokumen111 halamanTransmission Line ProtectioneccabadBelum ada peringkat

- Getting Started With DAX Formulas in Power BI, Power Pivot, and SSASDokumen19 halamanGetting Started With DAX Formulas in Power BI, Power Pivot, and SSASJohn WickBelum ada peringkat

- Portfolio Corporate Communication AuditDokumen8 halamanPortfolio Corporate Communication Auditapi-580088958Belum ada peringkat

- Chapter 6 Performance Review and Appraisal - ReproDokumen22 halamanChapter 6 Performance Review and Appraisal - ReproPrecious SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Dynamics of Fluid-Conveying Beams: Governing Equations and Finite Element ModelsDokumen22 halamanDynamics of Fluid-Conveying Beams: Governing Equations and Finite Element ModelsDario AcevedoBelum ada peringkat

- Capital Asset Pricing ModelDokumen11 halamanCapital Asset Pricing ModelrichaBelum ada peringkat

- Supply AnalysisDokumen5 halamanSupply AnalysisCherie DiazBelum ada peringkat

- MEETING OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Committee on University Governance April 17, 2024Dokumen8 halamanMEETING OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Committee on University Governance April 17, 2024Jamie BouletBelum ada peringkat

- Expert Java Developer with 10+ years experienceDokumen3 halamanExpert Java Developer with 10+ years experienceHaythem MzoughiBelum ada peringkat

- Midterm Exam SolutionsDokumen11 halamanMidterm Exam SolutionsPatrick Browne100% (1)

- SWOT Analysis of Fruit Juice BusinessDokumen16 halamanSWOT Analysis of Fruit Juice BusinessMultiple UzersBelum ada peringkat

- Readiness of Barangay Masalukot During TyphoonsDokumen34 halamanReadiness of Barangay Masalukot During TyphoonsJerome AbrigoBelum ada peringkat

- Screenshot 2021-10-02 at 12.22.29 PMDokumen1 halamanScreenshot 2021-10-02 at 12.22.29 PMSimran SainiBelum ada peringkat

- PSC Single SpanDokumen99 halamanPSC Single SpanRaden Budi HermawanBelum ada peringkat

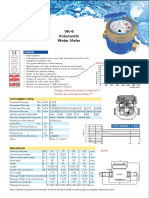

- Baylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterDokumen1 halamanBaylan: VK-6 Volumetric Water MeterSanjeewa ChathurangaBelum ada peringkat

- Auditing For Managers - The Ultimate Risk Management ToolDokumen369 halamanAuditing For Managers - The Ultimate Risk Management ToolJason SpringerBelum ada peringkat

- ITC Report and Accounts 2016Dokumen276 halamanITC Report and Accounts 2016Rohan SatijaBelum ada peringkat

- How To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingDokumen10 halamanHow To Google Like A Pro-10 Tips For More Effective GooglingMinh Dang HoangBelum ada peringkat

- Constitutional Law of India-II CCSU LL.B. Examination, June 2015 K-2002Dokumen3 halamanConstitutional Law of India-II CCSU LL.B. Examination, June 2015 K-2002Mukesh ShuklaBelum ada peringkat

- Danielle Smith: To Whom It May ConcernDokumen2 halamanDanielle Smith: To Whom It May ConcernDanielle SmithBelum ada peringkat

- CCW Armored Composite OMNICABLEDokumen2 halamanCCW Armored Composite OMNICABLELuis DGBelum ada peringkat

- Common Size Statement: A Technique of Financial Analysis: June 2019Dokumen8 halamanCommon Size Statement: A Technique of Financial Analysis: June 2019safa haddadBelum ada peringkat

- Steps To Private Placement Programs (PPP) DeskDokumen7 halamanSteps To Private Placement Programs (PPP) DeskPattasan U100% (1)

- MongoDB vs RDBMS - A ComparisonDokumen20 halamanMongoDB vs RDBMS - A ComparisonShashank GuptaBelum ada peringkat