POLITENESS PHENOMENA EXAMINED

Diunggah oleh

Whyna IskandarDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

POLITENESS PHENOMENA EXAMINED

Diunggah oleh

Whyna IskandarHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

POLITENESS PHENOMENA

Introduction Politeness phenomena are thus one manifestation of the wider concept of etiquette, or appropriate behavior. Grundy (2008) gives an example of how politeness is being used in the daily life. He mentioned two examples of how someone and his wife polite in different ways. This is happened because the distance between he and his wife on the one hand and between someone and he in the conversation on the other is not the same. This chapter will be discussed about the politeness phenomena and Brown and Levinsons theory which determine politeness phenomena such as, the power-distance relationship of interactants and the extent to which a speaker imposes on an addressee. The next discussion is about politeness phenomena in the real world, in which several real world politeness challenges are explored. The last section is the universal character of politeness, in which the claim that Brown and Levinsons schema captures universal properties of politeness is discussed. Body of the chapter 1. Politeness phenomena and Brown and Levinsons theory In their classic book on politeness, they argue that politeness phenomena extend the notion of indexicality because they show that every utterance is uniquely designed for its context. They also state that politeness phenomena are a paradigm example of pragmatic usage. In being polite, a speaker is attempting to create an implicated context that matches the one assumed by the addressee. In line with this, Aziz (2008) states on his journal that politeness is more widely used to refer to the act of speaking or interpersonal communication in order to avoid embarrassment of someone or both who involved in the communication. Added by Grundy (2008), politeness phenomena are thus one manifestation of the wider concept or etiquette, or appropriate behavior.

a. Face Within interaction, however there is a more narrowly specified type of politeness at work. Face means the public self-image of a person. It refers to that emotional and social sense of self that everyone has and expects everyone else to recognize. Politeness can be then defined as the means employed to show awareness of another persons face. Showing awareness for another persons face when that other seems socially distant is often in terms of respect or deference. Face wants. Within their everyday social interactions, people generally behave as if their expectations concerning their public self-image, or their face wants, will be respected. Alternatively given the possibility that some action might be interpreted as a threat to anothers face, the speaker can say something to lessen the possible threat. This called as a face saving act. Because it is generally expected that each person will attempt to respect the face wants of others, there are many different ways of performing grace saving acts (Yule: 1996). b. The effect of politeness Polite utterances encode the relationship between the speaker and the addressee, so that politeness affects both of them differently. As a part of the communication, we should know who is the addresser, the addressee and in what circumstances dos the utterances happened. In conclusion, the way we say things to each other has real effect. This is because it encodes not only propositional content but also out understanding of the relationship between the addressee and the addresser. This insight suggests that every instance of communicated language exhibits politeness. c. Redress and redundancy Grundy (2008) on his book that politeness phenomenon frequently go in the opposite direction of presupposition and pragmatic presupposition in particular, which encourage economical communication by allowing shared propositions to be taken for granted without being stated. Grundy also states that the more economical utterances are used when the speaker

knows the addressee well, and the more elaborate when the speaker knows the addressee less well. It means that in this section, we should more likely to use redressive, and hence less economical, linguistic formulas when we place demands on those we address, especially when we do not know them well. d. Power, distance, and imposition Grundy shows the nature of the relationship between the speaker and the addressee. He provides an example like this: someone at the bar enjoying a quiet drink. Two men come in and the one in front says to the barman (1) a pint of Bass please, he then consults his friend, who also wants a pint of Bass. The first man then says to the barman, can you make it two please. If the first man consulted his friend before ordering, he would of course have said two pints of Bass please in the first place. But because his order in two parts and because each part is for the same drink, he acknowledges this little extra imposition with can you make it., a yes/no question at the locutionary level which it is technically possible to answer no if you happen to be Mr. logic. In (1) and (2) the social distance and power relationship remains constant since two utterances involve the same two speakers, so the only variable is the degree of imposition of the request. Grundy makes a conclusion that in deciding on the redressive language needed when performing a speech act, we should take into account the degree of imposition of what we seek to accomplish by our utterance and any social distance or power differential between ourselves and those we address. e. Brown and Levinsons model of politeness strategies Face wants and face-threatening acts Universal in Language Usage: Politeness Phenomena (1978) was built by Brown and Levinson as the most fully elaborated work on linguistic politeness. Then, re-issued with a new introduction and revised bibliography as Politeness: Some Universal in Language Usage (1987).

Added by Tamil as speakers in southern India, Tzeltal speakers in Mexico and speakers of American and British English, they provide a systematic description of cross-linguistic politeness phenomena whisch is used to support an explanatory model capable of accounting for any instance of politeness. Their claim that broadly comparable linguistic strategies are available in each language but that there are local cultural differences in what triggers their use. Brown and Levinson work with Goffmans notion of face, a property that all human beings have and thats broadly comparable to self-esteem. In most encounters, our face is put a t risk, for example: asking someone for a sheet of paper or asking someone the time. So when we perform such actions, they are typically accompanied with redressive language design to compensate the treat to face and thus to satisfy the face wants of our interlocutor. Brown and Levinson assume a Model Person with two kinds of face, positive face and negative face. Positive face is a persons wish to be well thought of. Its manifestatios may include the desire to have others admire what we value, the desire to be understood by others, and the desire to be treated as a friend and confidant. Thus a complaint about the quality of someones work threatens their positive dace. Negative face is our wish to be imposed on by others and to be allowed to go about our business unimpeded and with our rights to free and self determined action intact.

Positive, negative and off-record politeness When someone has a face-threatening act to perform, Brown and Levinsons Model Person chooses from three superordinate strategies. By on record, Brown and Levinson mean without attempting to hide what we are doing, and by off-record they mean in such a way as a pretend to hide in, for example: I dont know whats wrong with my mobile-it doesnt seem to be charged. That example might well be an off-record way of hinting that someone asks other to let them hers.

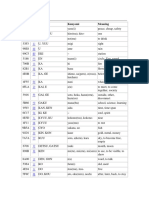

Grundy provide another example: Shopper: excuse me you havent got a pound coin have you Peter : probably <produces coin from pocket> Shopper: there you are theres your two fifties From the example, we can see that the shopper chooses to go on record, and she decides to appeal to peters negative face, it is indicating that she is impeding peters right to go about daily business uninterrupted. The negative declarative and the tag encode that she does not necessarily expect me to satisfy her face wants. Grundy states on his book that an important point about Brown and Levinson five strategies is that they are ranked from Do the act on record badly, which has no linguistically encoded redress, through a sequence of escalating to be redressed by any language formula so that the most appropriate politeness strategy is no to do the act. A speaker will only choose a highly ranked strategy where the face threat is felt to be high, since being too polite implies that one is asking a lot of someone and/or that theres a significant poser or social distance differential between those involved. Positive and negative politeness strategies Brown and Levinson (1987:102,131) list the positive and negative politeness available to their Model Person, as bellow: Positive politeness: Notice/attend to hearers wants. Exaggerate interest/approval. Intensify interest. Use in-group identity markers. Seek agreement. Avoid disagreement. Presuppose/assert common ground. Joke. Assert knowledge of hearers wants. Offer, promise. Be optimistic. Include speaker and hearer in the activity. Give (or ask for) reasons. Assume/assert reciprocitv. Give gifts to hearer. Negative politeness:

Be conventionally indirect. Question, hedge. Be pessimistic. Minimize imposition. Give deference. Apologize. Impersonalize. State the imposition as a general rule. Nominalize. Go on record as incurring a debt.

f. Folk beliefs and pragmatic insight Much of our everyday thinking about politeness is bedeviled by the fact politeness is a folk term used in the kind of value-laden way. In Britain politeness is typically used to describe negative politeness, which is presumed to be a good thing. Like the example below: Susies butters gone and my cheese has gone as well was a more polite way of conveying the proposition already conveyed by someones been nicking stuff out the fridge. Grundy states on his book that politeness is the term we use to describe the relationship between how something is said to an addressee and that addressees judgment as to how it should be said. This has nothing at all to do with prescriptive approaches to linguistic etiquette.

2. Politeness phenomena in the real world This section will be discussed about positive and negative politeness are blended, and then consider speaker-and addressee-oriented face-saving strategies, before finally exploring a hotel guest whod had enough and resorted to rudeness. a. Service encounters and identify Will anyone leaving us in York please make sure you take all your personal belongings with you From the example above, it is usual to address both positive as well as negative face wants even in a service encounter that encodes the fundamentally unequal status of costumer and service provide. The example above used plain and friendly make sure immediately after an

impersonal anyone, nominalized anyone leaving, power-encoding us, and the redressive please b. Face-saving formulas for the speaker: a long day The situation is in the airport, the speaker in the airport departure lounge at 8:45 a.m waiting for the call to go to the gate. There is a passenger in a wheelchair nearby. In due course, a member of staff appears and asks the passenger appears if he needs assistance getting to the gate. The passenger points out that the member of the staff has already offered him assistance, and rather ungraciously adds Passenger : .. youre getting confused Staff manager : its been a long day Passenger : and it hasnt even started yet If we see anyone in a wheelchair at Newcastle airport, my advice is to leave them to it. Although we usually think of the face of the addressee being threatened, we should also remember that the speakers too can easily lose face. c. Maintaining addressee face when wants arent met Guest : do you have any nice girls in the hotel tonight? Bellboy : oh no, Im afraid not. But you may go across the road. From the example above, we have already noticed that when we make a request which the person we address cannot satisfy, they tend and minimize our face loss. Sometimes there is an alternative suggestion, as on this occasion when the bellboys but encodes his metapragmatic awareness of making a next-best suggestion. d. A hotel breakfast This example taken form Grundy (2008) Waiter : have you had breakfast here before Peter : sorry Waiter : have you had breakfast here before Peter : I only arrived here yesterday

We can see from the example, rather than responding to the first question with no I have not, Peter felt it was to challenge the interrogation with sorry. When the question was repeated, Peter decided to let the waiter infer that obviously had not had breakfast before from I only arrived here yesterday. It was rude, and it turned out that the waiter had decided not to bother about the fact that Peter did not exist on the waiters list. So Peter looked even more foolish. On the conclusion, we can draw from this misunderstanding is that politeness phenomena, because of their redressive function, enable civilized exchanges to occur. When politeness is left behind, as here, things can go wrong very quickly. A couple more questions from the waiter and I might have resorted to striding past him and risking fisticuffs. 3. The universal character of politeness Brown and Levinson argue that politeness phenomena are universal. In hierarchical societies with strong class distinctions, the over-classes will see to it that the under-classes employ more negative politeness strategies when addressing their elders and betters as a way of encoding and thus maintaining the distance between socially stratified groups who acquire face status through birth. More egalitarian societies, on the other hand, will employ positive politeness strategies as a way of encoding and thus confirming a less territorial view of face. On the other hand, Matsumoto (1988) argue that in Japanese the structures associated with negative politeness strategies in Brown and Levinsons model do not have a negative politeness function but instead constitute a social register. Much of Matsumotos criticism centers on the way that deference is manifested in Japanese honorifics. She claims that deference can be equated with the speakers respecting an individuals right to non imposition. She suggest us to distinguish situations where deference given unexceptionally as an automatic acknowledgement of relative social status

from situations where it is given exceptionally in a particular situation as a redressive strategy. In the first case, the use of honorifics reinforces an existing culture and is not a chosen politeness strategy at all since the speaker attempts to produce a context-reflecting utterance acceptable to the addressee as addressee. In the second, the speaker uses deference to produce a contextcreating, utterance acceptable to the addressee in the situation shared by the speaker and himself. Whether Brown and Levinson have proposed a model that is universal is always open to discussion. But what is important about their work is their observation that politeness is not equally distributed. As they say: it is not as if there were some basic modicums of politeness owed by each to all. Rather what is owed depends on the calculation of what is expected in each social and situational context that arises.

Synthesis/comment A linguistic interaction is necessarily a social interaction. Factors which relate to social distance and closeness are established prior to interaction. They typically involve the relative status of the participants, based on social values ties to such things as age and power. We should take part in a wide range of interactions where the social distance determined by external factor is dominant. However, there are other factors, such as amount of imposition or degree of friendliness, which are often negotiated during in interaction. These internal factors are typically in the process of being worked out within the interaction. Both type of factors, external and internal have an influence not only on what we say but also on how we are interpreted. Recognizing the impact is normally carried out in terms of politeness. Politeness is the term we use to describe the relationship between how something is said to an addressee and that addressees judgment as to how it should be said. This has nothing at all to do with perspective approaches to linguistic etiquette.

References Aziz, E.A. 2008. Horison Baru Teori Kesantunan Berbahasa. Guru Besar Linguistik pada Fakultas Pendidikan Bahasa UPI Oktober 2008. Grundy, Peter. 2008. Doing Pragmatics. Third edition. UK: Hooder education. Thomas, Jenny. (1975). Meaning in Interaction: An Introduction to Pragmatics. New York: Longman. Yule, George. 1996. Pragmatics. Hongkong: Oxford University Press.

CHAPTER REPORT Submitted as a partial fulfillment of Language in Use assignment

By Pratiwi Rahayu: 1201150 Tuhfa Noviana Harun: 1202215 Wiena Novianti: 1200883

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH EDUCATION SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES INDONESIA UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION 2013

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Present Continuous Test A1 - A2 Grammar ExercisesDokumen4 halamanPresent Continuous Test A1 - A2 Grammar ExercisesFred MontBelum ada peringkat

- Prepositions of PlaceDokumen4 halamanPrepositions of PlaceanungBelum ada peringkat

- Past Tense Verb Forms Explained: Simple Past vs Past PerfectDokumen4 halamanPast Tense Verb Forms Explained: Simple Past vs Past PerfectAna KosBelum ada peringkat

- C1 Writing Assessment 3 Phobias PDFDokumen7 halamanC1 Writing Assessment 3 Phobias PDFAndersson Benito HerreraBelum ada peringkat

- Saxon Norman Genitive FridayDokumen22 halamanSaxon Norman Genitive Fridayswetty19100% (1)

- PET Writing A Letter B1 My TownDokumen2 halamanPET Writing A Letter B1 My Towngabi100% (1)

- Pronoun and Its TypesDokumen9 halamanPronoun and Its TypesRosita BagusBelum ada peringkat

- The Relative Clauses - ActivitiesDokumen26 halamanThe Relative Clauses - ActivitiesBondfriendsBelum ada peringkat

- Strong and Weak Forms Practice + KeyDokumen3 halamanStrong and Weak Forms Practice + KeyMarco MichienziBelum ada peringkat

- Expression of Human Character in Phraseological UnitsDokumen6 halamanExpression of Human Character in Phraseological UnitsCentral Asian StudiesBelum ada peringkat

- Life UI 1c Bloodlines LessonDokumen3 halamanLife UI 1c Bloodlines LessonDanille VamhamBelum ada peringkat

- Modals and Modal PerfectsDokumen3 halamanModals and Modal PerfectsAnonymous d5q96ww4vnBelum ada peringkat

- Cleft Sentences Grammar and Exercises b1Dokumen11 halamanCleft Sentences Grammar and Exercises b1Emilyn PalomoBelum ada peringkat

- Phrasal Verb Exercises - Murcia EOIDokumen3 halamanPhrasal Verb Exercises - Murcia EOIJose MorcilloBelum ada peringkat

- Reading ComprehensionDokumen4 halamanReading Comprehensiondurgasaraswathi9111100% (1)

- The Weaknesses of Grammar Translation MethodDokumen3 halamanThe Weaknesses of Grammar Translation MethodSaraBelum ada peringkat

- Description: 3. Can Understand Basic Personal Details If Given Carefully and SlowlyDokumen5 halamanDescription: 3. Can Understand Basic Personal Details If Given Carefully and SlowlyLuz Mery MurciaBelum ada peringkat

- A2 - Exercise For Cleft Sentence (Rechecked)Dokumen3 halamanA2 - Exercise For Cleft Sentence (Rechecked)KheangBelum ada peringkat

- Subject: English (Prepositions) A. Look at The Picture and Fill in The Blanks With The Correct PrepositionsDokumen3 halamanSubject: English (Prepositions) A. Look at The Picture and Fill in The Blanks With The Correct PrepositionsMamberamo ClassBelum ada peringkat

- PSAT Identifying Sentences PracticeDokumen3 halamanPSAT Identifying Sentences PracticeRandeep MalikBelum ada peringkat

- Simple Past QuestionDokumen2 halamanSimple Past QuestionAlexandre RodriguesBelum ada peringkat

- 2.1. Noun Possessive CaseDokumen10 halaman2.1. Noun Possessive CaseAna DerilBelum ada peringkat

- DeceptionDokumen2 halamanDeceptionRisma Halimatussa'diahBelum ada peringkat

- LESSON PLAN ENGLISH Docx 1Dokumen2 halamanLESSON PLAN ENGLISH Docx 1Camille De GuzmanBelum ada peringkat

- Holiday Bingo: Activity TypeDokumen4 halamanHoliday Bingo: Activity TypeMariana Olmedo100% (1)

- Few A Few Little and A LittleDokumen2 halamanFew A Few Little and A LittleIva Waya VasiljevBelum ada peringkat

- Writing An Informal Letter PDFDokumen1 halamanWriting An Informal Letter PDFvero_poluxBelum ada peringkat

- Student Guide #4: Grammar For Writing: Reduced Adjective ClausesDokumen7 halamanStudent Guide #4: Grammar For Writing: Reduced Adjective ClausesLORAINE CAUSADO BARONBelum ada peringkat

- Grammar Basics Object PronounsDokumen1 halamanGrammar Basics Object PronounsCremilson Ramos50% (2)

- Whats Your OpinionDokumen2 halamanWhats Your OpinionFlor Henríquez100% (1)

- First Conditional WorksheetDokumen2 halamanFirst Conditional WorksheetMario Sanabia FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan: Materials Presentation Notebook Speakers Video Interactive BoardDokumen4 halamanLesson Plan: Materials Presentation Notebook Speakers Video Interactive BoardZhansaya KaldarbekovaBelum ada peringkat

- Exercise 9.compare and Contrast Paragraph - Language PracticeDokumen4 halamanExercise 9.compare and Contrast Paragraph - Language PracticeTạ Minh HuyềnBelum ada peringkat

- Metonimies in Vietnamese and EnglishDokumen91 halamanMetonimies in Vietnamese and EnglishHà Stella100% (1)

- The Best British Short StoriDokumen178 halamanThe Best British Short Storianilyar91gmailcomBelum ada peringkat

- Passive Voice and Active VoiceDokumen104 halamanPassive Voice and Active VoiceLuis Serrano CortezBelum ada peringkat

- The Prepositions at in On 2Dokumen5 halamanThe Prepositions at in On 2Eric Erik0% (1)

- Go - Uses and Expressions PDFDokumen2 halamanGo - Uses and Expressions PDFJosé Manuel Henríquez GalánBelum ada peringkat

- Possessive Adj - Possessive PronounDokumen6 halamanPossessive Adj - Possessive PronounC2 Bần TrườngBelum ada peringkat

- Preposition Comb ReviewDokumen5 halamanPreposition Comb ReviewyehighBelum ada peringkat

- Word Order Rules and Exercises PDFDokumen10 halamanWord Order Rules and Exercises PDFgabriella56Belum ada peringkat

- Re-Arrange The Sentence.: Write The Verb To Be and Change To Short FormDokumen9 halamanRe-Arrange The Sentence.: Write The Verb To Be and Change To Short FormLina CherifBelum ada peringkat

- Possessive PronounsDokumen1 halamanPossessive PronounsAbbie WanyiiBelum ada peringkat

- Pragmatics: Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nguyen Quang NgoanDokumen48 halamanPragmatics: Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Nguyen Quang NgoanTran thanh thuy Nguyen100% (1)

- Present Simple and Present ContinuousDokumen4 halamanPresent Simple and Present ContinuousZolde JuliaBelum ada peringkat

- ConditionalDokumen23 halamanConditionalLance Nicole VillasisBelum ada peringkat

- Restaurant Service Training ShowDokumen20 halamanRestaurant Service Training ShowHuy Nguyễn Phan TrườngBelum ada peringkat

- 12 Aprilie Means of Expressing FuturityDokumen7 halaman12 Aprilie Means of Expressing FuturityAnaBelum ada peringkat

- Connectors and Linkers GuideDokumen3 halamanConnectors and Linkers GuideAnonymous 8AHCMsPuBelum ada peringkat

- Handout Second ConditionalDokumen2 halamanHandout Second ConditionalFatima C. DiazBelum ada peringkat

- Gerund, Definition, Examples, Uses, Rules, Exercise or WorksheetDokumen6 halamanGerund, Definition, Examples, Uses, Rules, Exercise or WorksheetGan Penton0% (1)

- APA Format Find The Citation ErrorDokumen25 halamanAPA Format Find The Citation ErrorMaryam Al MarzouqiBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Degrees of ComparisonDokumen5 halamanUnderstanding Degrees of ComparisonIrmHaSoSweetBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 2Dokumen31 halamanChapter 2CA Pham KhaiBelum ada peringkat

- 22 The Great Vowel ShiftDokumen4 halaman22 The Great Vowel ShiftRoma Shchur100% (1)

- Reported Speech CommandsDokumen2 halamanReported Speech CommandsEvelyn GualdronBelum ada peringkat

- Relative Clause NoteDokumen7 halamanRelative Clause NoteFriska WijayaBelum ada peringkat

- Group dDokumen19 halamanGroup dAnthonette Ome-AkpotuBelum ada peringkat

- Pragmatic PolitenessDokumen9 halamanPragmatic PolitenessMarlina Rina LukmanBelum ada peringkat

- Brown & Levinson's Politeness Theory HandoutDokumen5 halamanBrown & Levinson's Politeness Theory HandoutSebastian WasserzugBelum ada peringkat

- REFERENCES LISTDokumen9 halamanREFERENCES LISTWhyna Iskandar100% (1)

- Academic Cover LettersDokumen5 halamanAcademic Cover Letterscoxo_designBelum ada peringkat

- Computer English 1Dokumen11 halamanComputer English 1Whyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- 4theeffectofguessingvocabularyinreadingauthentictextsamongpre UniversitystudentsDokumen15 halaman4theeffectofguessingvocabularyinreadingauthentictextsamongpre UniversitystudentsWhyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- Contoh SilabusDokumen5 halamanContoh SilabusWhyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- PragmaticsDokumen51 halamanPragmaticsWhyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- Ini Baru Metlit ResearchDokumen9 halamanIni Baru Metlit ResearchWhyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- Transactional TheoryDokumen26 halamanTransactional TheoryWhyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- Pragmaticsimplicature2 120417232642 Phpapp01Dokumen21 halamanPragmaticsimplicature2 120417232642 Phpapp01Whyna IskandarBelum ada peringkat

- Grade 6 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachDokumen8 halamanGrade 6 Daily Lesson Log: Write The LC Code For EachDarwin SolanoyBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 15-16-20 True or FalseDokumen2 halamanUnit 15-16-20 True or FalseDi TiểuBelum ada peringkat

- Bangla AbcdDokumen6 halamanBangla Abcdrahulchow2Belum ada peringkat

- Plan de estudios del área de Lengua Extranjera - Inglés optimizado para SEODokumen73 halamanPlan de estudios del área de Lengua Extranjera - Inglés optimizado para SEOLiliana Montoya GomezBelum ada peringkat

- English Verb Patterns 25 List (Total 52) by AS HonbyDokumen2 halamanEnglish Verb Patterns 25 List (Total 52) by AS Honbydigitalpapers86% (22)

- 300 Forms of Verbs For Basic English Learners With Urdu Meaning Part 3Dokumen21 halaman300 Forms of Verbs For Basic English Learners With Urdu Meaning Part 3Amirhamayun KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Bottom-Up Parsing OverviewDokumen21 halamanBottom-Up Parsing OverviewKANSIIME KATEBelum ada peringkat

- Phonetics: English DepartmentDokumen10 halamanPhonetics: English DepartmentArya PramanaBelum ada peringkat

- Coursemandarin00mate PDFDokumen862 halamanCoursemandarin00mate PDFatabeg7Belum ada peringkat

- Autumn Weather and Fruits Lessons for English ClassDokumen27 halamanAutumn Weather and Fruits Lessons for English ClassmikhelangeloBelum ada peringkat

- The English Fluency FormulaDokumen46 halamanThe English Fluency Formulaabdulsamad93% (15)

- The Beatles The Fool On The HillDokumen6 halamanThe Beatles The Fool On The Hillaitorr_aitorrBelum ada peringkat

- Materi 10 Passive Voice, Subjunctive, Corelative ConjunctionDokumen6 halamanMateri 10 Passive Voice, Subjunctive, Corelative Conjunctionindri suprianiBelum ada peringkat

- Week13 Input InteractionDokumen13 halamanWeek13 Input InteractionHaziqah DiyanaBelum ada peringkat

- mARUNGPO APPROACHDokumen1 halamanmARUNGPO APPROACHAnne Harvey BuatisBelum ada peringkat

- Unit Three Planning Waste Not Want NotDokumen30 halamanUnit Three Planning Waste Not Want Notslt100% (1)

- Assignment Parts of SpeechDokumen2 halamanAssignment Parts of SpeechFarman Ali KhaskheliBelum ada peringkat

- General Guidelines for TranscriptionsDokumen8 halamanGeneral Guidelines for TranscriptionsJacqueline del RosarioBelum ada peringkat

- 10 0861 01 2RP AFP tcm143-701168Dokumen8 halaman10 0861 01 2RP AFP tcm143-701168pranavmahesh3010Belum ada peringkat

- 849 Type1Dokumen14 halaman849 Type1mjBelum ada peringkat

- KELOMPOK 1 Bahasa InggrisDokumen10 halamanKELOMPOK 1 Bahasa InggrisshellomitaBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson ScriptDokumen2 halamanLesson Scriptapi-489861652Belum ada peringkat

- Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: Proto-Indo-European LanguageDokumen19 halamanIndo-European and the Indo-Europeans: Proto-Indo-European Languagetenshinhan2000Belum ada peringkat

- Kanji N5Dokumen4 halamanKanji N5Michelle DarmawanBelum ada peringkat

- SAYING I LOVE YOU in Different LanguagesDokumen5 halamanSAYING I LOVE YOU in Different LanguagesDiana100% (1)

- Writing - Useful Words and Phrases - FCE: Making PointsDokumen7 halamanWriting - Useful Words and Phrases - FCE: Making PointsNifty100% (1)

- James D. Gentry - Objects of Power in The Life of Sog Bzlog Pa (PHD) PDFDokumen561 halamanJames D. Gentry - Objects of Power in The Life of Sog Bzlog Pa (PHD) PDFkabul87Belum ada peringkat

- Vancova Phonetics and Phonology 2016 PDFDokumen99 halamanVancova Phonetics and Phonology 2016 PDFmaruk26Belum ada peringkat

- RPHDokumen3 halamanRPHLau Su EngBelum ada peringkat

- Adjectives & AdverbsDokumen5 halamanAdjectives & AdverbsazahidulBelum ada peringkat