Archer Taylor The Origins of The Proverb

Diunggah oleh

Maria AdamJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Archer Taylor The Origins of The Proverb

Diunggah oleh

Maria AdamHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

ARCHER TAYLOR THE ORIGINS OF THE PROVERB* THE definition of a proverb is too difficult to repay the undertaking; and

should we fortunately combine in a single definition all the essential elements and give each the proper emphasis, we should not even then have a touchstone. An incommunicable quality tells us this sentence is proverbial and that one is not. Hence no definition will enable us to identify positively a sentence as proverbial. Those who do not speak a language can never recognize all its proverbs, and similarly much that is truly proverbial escapes us in Elizabethan and older English. Let us be content with recognizing that a proverb is a saying current among the folk. At least so much of a definition is indisputable, and we shall see and weigh the significance of other elements later. The origins of the proverb have been little studied. We can only rarely see a proverb actually in the making, and any beliefs we have regarding origins must justify themselves as evident or at least plausible. Proverbs are invented in several ways: some are simple apothegms and platitudes elevated to proverbial dignity, others arise from the symbolic or metaphoric use of an incident, still others imitate already existing proverbs, and some owe their existence to the condensing of a story or fable. It is convenient to distinguish as "learned" proverbs those with a long literary history. This literary history may begin in some apt Biblical or classical phrase, or it may go back to a more recent source. Such "learned" proverbs differ, however, in only this regard from other proverbs. Whatever the later history may be, the manner of ultimate invention of all proverbs, "learned" or "popular," falls under one or another of the preceding heads. It is not proper to make any distinction in the treatment of "learned" and "popular" proverbs. The same problems exist for all proverbs with the obvious limitation that, in certain cases, historical studies are greatly restricted by the accidents of preservation. We can ordinarily trace the "learned" proverb down a long line of literary tradition, from the classics or the Bible through the Middle Ages to the present, while we may not be so fortunate with every "popular" proverb. For example, Know thyself may very well have been a proverb long before it was attributed to any of the seven wise men or was inscribed on the walls of the temple of Delphic Apollo. Juvenal was nearer the truth when he said it came from Heaven: "E caelo descendit " (Sat., xi, 27). Yet so far as modern life is concerned, the phrase owes its vitality to centuries of bookish tradition. St. Jerome termed Don't look a gift horse in the mouth a common proverb, when he used it to refer to certain writings which he had regarded as free will offerings and which critics had found fault with: "Noli (ut vulgare est proverbium) equi dentes inspicere donati." We cannot hope to discover whether the modern proverb owes its vitality to St. Jerome or to the vernacular tradition on which he was drawing. St. Jerome also took The wearer best knows where the shoe wrings him from Plutarch, but we may conjecture that this proverb, too, was first current on the lips of the folk. Obviously the distinction between "learned" and "popular" is meaningless and is concerned merely with the accidents of history.

PROVERBIAL APOTHEGMS

Often some simple apothegm is repeated so many times that it gains proverbial currency: Live and learn; Mistakes will happen; Them as has gets; Enough is enough; No fool like an old fool; Haste makes waste; Business is business; What's done's done. Characteristic of such proverbs is the absence of metaphor. They consist merely of a bald assertion which is recognized as proverbial only because we have heard it often and because it can be applied to many different situations. It is ordinarily difficult, if not impossible, to determine the age of such proverbial truisms. The simple truths of life have been noted in every age, and it must not surprise us that one such truth has a long recorded history while another has none. It is only chance, for example, that There is a time for everything has a long history in English,-Shakespeare used it in the Comedy of Errors, ii, 2: "There's a time for all things,"--and it is even in the Bible: "To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven" (Omnia tempus habent, et suis spatiis transeunt universa sub caelo, Eccles. iii, I), while Mistakes will happen or If you want a thing well done, do it yourself have, on the contrary, no history at all.

The full text of this article is published in De Proverbio - Issue 3:1996 & Issue 4:1996, an electronic book, available from amazon.com and other leading Internet booksellers.

PROVERBIAL TYPES New proverbs have often been made on old models. Certain frames lend themselves readily to the insertion of entirely new ideas. Thus the contrast in Young . . ., old . . . in such a proverb as Young saint, old devil yields a model for Junge Bettschwester, alte Betschwester. A methodical comparison would probably reveal the proverb which gave the original impulse to the formation of the others; but no one has ever undertaken a study of this sort. Martha Lenschau conceives the development as follows: Young angel, old devil (Jung Engel, alt Teufel, thirteenth century); i.Young knights, old beggars (Junge Ritter, alte Bettler, sixteenth century); Young soldiers, old beggars (Junge Soldaten, alte Bettler, seventeenth century). The first form made no distinction for sex. When the substitution of "knight" or "soldier" made the distinction, a by-form for women was invented on the same model: Junge Hure, alt Kupplerin appears to have been the first of such by-forms, although Jung Hure, alt Wettermacherin must also be ancient, since the notion involved in "Wettermacherin" reaches far back. The most recent development is probably the Low German Young gamblers, old beggars (Junge Spler, ole Bedler), and the corruption Young musicians, old beggars (Junge Musikanten, alde Beddellde), which arises from the misunderstanding of "Spler," 'players' (i. e. gamblers), as 'players of music' and the later substitution of a synonym. It is not always easy to recognize or identify the earliest form which provided the model for later developments; and until several proverbs have been minutely examined from this point of view and our methods of study have been improved, it is hard to say which arguments are safe to use and which are unsafe. In all probability, we may trust to the general principles which have been worked out for mrchen, i. e. those employed in the so-called Finnish or historico-geographical method. The relative age and distribution of the various forms of a proverb will throw much light on the development. In the present instance, for example, we

might regard the old and widely known Jung gewohnt, alt getan ('What one is accustomed to in youth, one does in old age') as a possible model, even of the whole group. Certainly it has given us Jung gefreut, alt gereut (' Rejoiced in youth, repented in age') and as a secondary development: Jung gefreit, alt gereut ('Married in youth, repented in age'). Since, however, Young saint, old devil is even older and more widely known, I am inclined to consider it the parent of all later forms. Often other arguments than age and wide currency may be brought into court. Usually, a dialectal variation which is essential to a particular form and which limits it to a narrow area is secondary in origin, e. g. Jung gefreit, alt geklait ('Wed in youth, bewailed in old age') can have arisen only in a region where 'geklagt' is pronounced "geklait." So, too, Jung gefreit, alt gereut originated in a region--somewhat larger, to be sure, than the one just mentioned--where the dialectal pronounciation of "gereut" made the rhyme tolerable. A few more illustrations of the creation of new proverbs on the model of old ones will suffice. A familiar German proverbial type employs the notion that the essential qualities of an object show themselves the very beginning, e. g. Was ein Hkchen werden soll, krmmt sich beizeiten (' Whatever is to be a hook, bends early'). English representatives of this type are rare, but we may cite Timely crooks that tree that will be a cammock (i. e. 'gambrel,' a bent piece of wood used by butchers to hang carcasses on) and It pricketh betimes that shall be a sharp thorn. A German derivative of the type is Was ein Nessel werden soll, brennt beizeiten ('Whatever is to be a nettle, burns early'). This proverb has found rather wide currency. Although the evidence is not all in, the type or at least its ready employment in new proverbs is German. The form characteristic of Es sind nicht alle Jger die das Horn blasen ('They are not all hunters who blow horns'), a form which appears to have been first recorded by Varro ('Non omnes, qui habent citharam, sunt citharoedi'), enjoyed a remarkable popularity in mediaeval Germany and gave rise to many new proverbs, e. g. They are not all cooks who carry long knives (Es sind nicht alle Kche, die lange Messer tragen); They are not all friends who laugh with you (Zijn niet alle vrienden, die hem toelachen). Outside of Germany and countries allied culturally, the form appears to have had no notable success, except in All is not gold that glitters, which refers to a thing and not a person. Seiler thinks that" Many are called, but few are chosen" (Multi enim sunt vocati, pauci vero electi, Matt. xx, 16; xxii, 14) was the ultimate model for these proverbs, but the similarity is one of thought and not of form. Possibly one could imagine a class based on simple balance and contrast, of which the young-old type and the called-chosen type might both be derivatives, but the fundamental differences in syntactical structure speak strongly against a development of this sort. Young saint, old devil is an old proverbial form which has no verb; Many are called, but few are chosen consists of balanced, antithetical sentences; All is not gold that glitters uses a subordinate clause. The syntactical differences are so great that an influence from one of these types on another does not seem likely.

The full text of this article is published in De Proverbio - Issue 3:1996 & Issue 4:1996, an electronic book, available from amazon.com and other leading Internet booksellers.

Of course there have been serious accidents occasionally in the passage from Latin into the modern languages, and, furthermore, various modern proverbs have been regarded as

descendants of Latin phrases, although the context shows clearly enough that the similarity is merely verbal and does not involve the transmission of ideas. Virgil's "A chill snake, lads, lurks in the grass" (Frigidus, o pueri, latet anguis in herba, Ecl., iii, 93) is not the source of the idea in our proverb A snake in the grass. The saying When the horse is stolen, lock the barn door cannot rest on a misunderstanding of Juvenal's words: "If in all the world you cannot show me so abominable a crime, I hold my peace; I will not forbid you to smite your breast with your fists, or to pummel your face with open palm, seeing that after so great a loss you must close your doors, and that a household bewails the loss of money with louder lamentations than death" (Sat., iii, 126 ff.). The reference concerns the Roman custom of closing doors as a sign of mourning. It is wisest not to think of any connection between Juvenal and the proverb and to regard the proverb as a peasant's invention and as comparable to such sayings as To cover the well after the child is drowned. We may observe in passing that the substitutions which occur in the variants are quite in the manner of oral tradition: for "horse" we have "cow" or "cattle" and for "lock" we have "repair." But further illustration of such substitutions is unnecessary: proverbs live the same sort of life in tradition, whatever their past history.

Notes *Reprinted from Archer Taylor The Proverb and An Index to "The Proverb", Sprichwrterforschung Band 6, Herausgegeben von Wolfgang Mieder, Peter Lang, BernFrankfurt am Main-New York, 1985, pp. 3-65 1. 1. 1. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Heusler, Zeitschrift des Vereins fr Volkskunde, XXV (1915), 11o, No. 1. The same, 113, No. 27. The same, 113, No. 4. An old maxim. Compare Caute, si non caste. In France, our soldiers paraphrased it as If you can't be good, be sanitary. Possibly we can see a connection with Laissez faire George, il est homme d'ge, a historical proverb. We are told that Louis XII expressed his confidence in his minister, George d'Amboise, in these words. The traditional explanation in America is based on "George" as a name used in addressing Pullman porters Cf. "Argens fait le jeu" (Baudoin de Sebourc, xxiv, 443). Primitive Culture, I. ch. iii, 89-90. See the bibliography in Bonser, Proverb Literature (London, 1930), p. 434, Nos. 3791-3797. Sea proverbs have been collected for their own sake. Perhaps the first work which makes special mention of such proverbs is a Dutch dictionary of sea terms (W. A. Winschoten, Seeman [Leiden, 1681]). F. A. Stoett extracts some curious superstitions and words from this work; see "W. A. Winschoten's Seeman," De Nieuwe Taalgids, XIII (1919), 97-106. For Dutch sea proverbs see van Dam van Isselt, Nederlandsche Muzen-Almanak (1838), pp. 135-139, and particularly Sprenger van Eijk

6. 7. 8. 9.

(Handleiding tot de Kennis van onze Vaderlandsche Spreekwoorden . . . van de Scheepvaart en het Scheepsleven Ontleend [Rotterdam 1835-36]). D. H. van der Meer (Verzameling van Stukken betreffende de Friesche Geschiedenis, etc. [Franeker, n.d.], I, 121-133) notes some Frisian sea proverbs. Sbillot (Lgendes, Croyances, et Superstitions de la Mer [Paris, 1886-87]) and Corbire ("Des Proverbes Nautiques," Revue de Rouen et de la Normandie, Vol. XIII [1845]) collect French examples. English and German collections have been made by Cowan (A Dictionary of the Proverbs and Proverbial Expressions Relating to the Sea [Greenesburgh, Pennsylvania, 1894]), Lypkes (Seemannssprche [Berlin, 1900]), and in the anonymous Sea Words and Phrases along the Suffolk Coast (Lowestoft, 1869-70), a reprinting of articles from the East Anglian Notes and Queries, January, 1869 and January, 1870. 10. See the bibliography in Bonser, Proverb Literature (London, 1930), pp. 447-448, Nos. 3914-3927. 11. Zaragoza, 1899. 12. See Otto, Die Sprichwrter und Sprichwrtlichen Redensarten der Rmer (Leipzig, 1890), p. xxv; Bolte and Polvka, Anmerkungun zu den Kinder- und Hausmrchen, IV (1930) , 116 n. ll, 365; "Fabel" in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopdie; Crusius, "Mrchenreminszenzen im Antiken Sprichwort," Verhandlungen d. 40. i.Philologenversammlung zu Grlitz (1890); L. Friedlnder, Bilder aus der Rmischen Sittengeschichte, I (5th ed., 1881), 469 ff., I (6th ed.,1888), 522 ff.; Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte (Berlin, 1920), pp. 71-86; Seiler, Lehnsprichwort, I, 22 f., 83 f.; Jente, "Mrchen im Sprichwort," Handbuch des Deutschen Mrchens (forthcoming). The article by Kasumovic (Rad of the Jugoslav Academy, CXCI, 195), which is cited in Zeitschrift des Vereins fr Volkskunde, XXIII (1913), 317, has not been accessible to me. 13. Nahum iii, 12. Quitard regards this passage as source; see p. 37. Compare Bchmann as above, p. 84. 14. Wesselski, Erlesenes (Gesellschaft Deutscher Bcherfreunde in Bhmen, VIII, Prague, 1928), p. 98. 15. For these and other examples see Voigt, Zeitschrift fr Deutsches Altertum, XXIII (1879), 294 (No. 30a), 305 (No. 11), 287 (No. 14), 301 (No. 58), 304 (No. 8). 16. Sprichwrter, p. xxv, where additional examples are given. He also believes that They have put a saddle on the ox; it is no task for me (Clitellae bovi sunt impositae plane, non est nostrum onus) is an allusion to a fable; cf. p. 262 and Archiv fr Lateinische Lexikographie, VI (1889), 9 n. 1. 17. See K. Euling, Das Priamel bis Hans Rosenplt (Germanistische Abhandlungen, No. 25), p. 179 n. 3; Strack, Hessische Bltter fr Volkskunde, II (1903), 69, 174; Die sterreich-Ungarische Monarchie in Wort und Bild (Vienna, 1891), VIII (Krnten und Krain), 151; A. Kopp, Ein Strusschen Liebesblten im Garten Deutscher Volksdichtung Gepflckt (Lelpzig, 1902),No. 19. See also the interesting remarks in the preface to D. Hyde, Songs of Connacht (Dublin, n.d.). Apparently a literary tradition lies behind the metrical form of certain Irish proverbs. 18. Wander, Deutsches Sprichwrter-Lexikon (Leipzig, 1867-80), s. v. Apfel, 6; Kopp, as above; Strack, as above, II, 174. 19. Estudios sobre Literatura Popular (Biblioteca de las Tradiciones Populares, Vol. V [Sevilla, 1884]), pp. 67-71, "Coplas sentenciosas," pp. 75-79, "Antinomia entre un refran y una copla." 20. See, for example, Krohn, "Die Entwicklung eines Sprichwortes zum Lyrischen Liede," Mlanges en l'Honneur de Vaclav Tille (Prague, 1929), pp. 109-112.

21. See the bibliography of collections of familiar quotations in Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte (Leipzig, 1912), p. xxvi. The more important collections are Arlaud, Bevingede Ord (Copenhagen, 1878); Bartlett, Familiar Quotations (Boston, 1924); Benham, Book of Quotations, Proverbs, and Household Words (London, 1924); Alexandre, Muse de la Conversation (Paris, 1902); Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte; der Citatenschatz des Deutschen Volkes (Leipzig, 1864, 1920); Nehry, Citatenschatz, Geflgelte Worte, Sprichwrter und Sentenzen (Leipzig, 1889); Winter, Unbeflgelte Worte (Augsburg, 1888); Fumagalli, Chi l'ha detto? Repertorio Metodico e Ragionato di 1575 Citazioni e Frasi di Origine Letteraria (Milan, 1895); Otto, Die Sprichwrter und Sprichwrtlichen Redensarten der Rmer (Leipzig, 1890); Curti, Schweizer Geflgelte Worte (Zurich, 1896); Ahnfelt, Bevingade Ord (Stockholm, 1879). 22. Altgermanische Dichtung (Handbuch der Literaturwissenschaft, Wildpark-Potsdam, 1923), p. 68, 61. 23. Ragnarssaga Lodbroka, 15; Kock and Petersen, Ostnordiska och Latinska Medeltidsordsprk (Copenhagen, 1889-94), II, 194; Bugge, Archiv fr Nordisk Filologi, X (1894), 96. 24. Wesselski, Angelo Polizianos Tagebuch (Leipzig, 1929), p. 45, No. 96. 25. Wesselski, Angelo Polizianos Tagebuch (Leipzig, 1929), p. 45, No. 96. 26. This may mean a pitchfork or a fork used to punish slaves. 27. Compare the examples of Latin quotations which verge on proverbs: Otto, Sprichwrter, p. xxii; Otto, Die Geflgelten Worte bei den Rmern (Breslau, 1890). See in general the many handbooks of familiar quotations, of which the most useful and most accurate is Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte (Berlin, 1920). 28. Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte (Leipzig, 1920), p. 456. 29. See Taylor, "The Death of Orvar Oddr," Modern Philology, XIX (1921), 93-106. 30. See in general Otto, p. xxii. 31. Since the Greek proverb employs the imperative, Erasmus is very likely justified in correcting the Latin to read "Let the die be cast" (Alea jacta esto). 32. Crusius makes some helpful remarks on this problem in his review of Otto, Wochenschrift fr Klassische Philologie, VIII (1891), coll. 428-429. See also Otto, pp. xviii-xix. 33. See Otto, pp. xviii-xix; Crusius, as above, col. 426. 34. "Die Beziehungen zwischen Slaven und Griechen in ihren Sprichwrtern," Archiv fr Slavische Philologie, XXX (1909), 1-47, 321-364. 35. "'Morgenstunde hat Gold im Munde,"' Publications Modern Language Association, XLII (1927), 865-872, see some additional material in Stoett, Nederlandsche Spreekwoorden (Zutphen, 1924-25), s. v. Morgenstond. 36. The special character of Biblical proverbs makes it possible to use collections and studies in any language. The more important reference works for such proverbs are found in Dutch and German: Kat, Bijbelsche Uitdrukkingen en Spreekwijzen in onze Taal (Zutphen, 1926); Laurillard, Bijbel en Volkstaal (Amsterdam, 1875; 2d ed., Rotterdam 1901), wlth the comments by Harrebome, Bedenkingen op het Prijsschrift van Dr. E. Laurillard (Gorinchem, 1877), Sprenger van Eijk, Handleiding tot de Kennis van onze Vaderlandsche Spreekwoorden (Rotterdam, 1835-41); Zeeman, Nederlandsche Spreekwoorden . . . aan den Bijbel Ontleend (Dordrecht, 1877, 1888); and Schulze, Die Biblischen Sprichwrter der Deutschen Sprache (Gttingen, 1860); Bchmann, Geflgelte Worte (Berlin, 1920), pp. 1-70. Biblical quotations and allusions in Old and Middle English literature are collected by A. S. Cook (Biblical Quotations in Old English Prose Writers [New York 1898-1903]) and Mary W. Smyth (Biblical Quotations in Old English before 1350 [New York, 1911]); although

these books are not primarily concerned wlth proverbial materials, they give an idea of the way in which the Bible was used and how Biblical proverbs may have arisen. Marvin (Curiosities in Proverbs [New York, 1916]) gives some miscellaneous and unsystematic notes on English Biblical proverbs. 37. "Ex abundantia . . . loquitur. Wenn ich den Eseln sol folgen, die werden mir die buchstaben furlegen, und also dolmetzschen: Auss dem berflus des hertzen redet der mund. Sage mir, Ist das deutsch geredet?"--Vom Dolmetschen (Weimar ed., XXX, ii, 637). 38. Cited by D. Murray, Lawyers' Merriments (Glasgow, 1912), p. 49; C. C. Nopitsch, Die Literatur der Sprichwrter (Nuremberg, 1833), p. 58; Wander, Deutsches Sprichwrter-Lexicon, s. v. Dieb, 170.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Sain Sucha-Memory - Poetry of Faiz Ahmad Faiz-Vudya Kitaban Forlag (1987) PDFDokumen82 halamanFaiz Ahmad Faiz, Sain Sucha-Memory - Poetry of Faiz Ahmad Faiz-Vudya Kitaban Forlag (1987) PDFAhmad JanBelum ada peringkat

- Types of compound wordsDokumen17 halamanTypes of compound wordsZAMMI AKHDAN IKHSANI 120610100% (1)

- The Dervishes, or Oriental SpiritualismDokumen443 halamanThe Dervishes, or Oriental SpiritualismVeena AnahitaBelum ada peringkat

- Hamza ShinwariDokumen6 halamanHamza ShinwariSami KakarBelum ada peringkat

- KhasiDokumen10 halamanKhasijgabilmomin67% (3)

- Pata Khazana Hidden TreasureDokumen241 halamanPata Khazana Hidden TreasureMehreen KhurshidBelum ada peringkat

- Home in the Poetry of Saudi Arabia Poets: Abdus-Salam Hafeth an Example of a Distinguished Arab (3) - الوطن في شعر شعراء المملكة العربية السعودية: عبد السلام حافظ كنموذج للشعر العربي المتميزDokumen3 halamanHome in the Poetry of Saudi Arabia Poets: Abdus-Salam Hafeth an Example of a Distinguished Arab (3) - الوطن في شعر شعراء المملكة العربية السعودية: عبد السلام حافظ كنموذج للشعر العربي المتميزYahya Saleh Hasan Dahami (يحيى صالح دحامي)100% (1)

- Kashmiri BibliographyDokumen95 halamanKashmiri BibliographyparasharaBelum ada peringkat

- Functions of Intonation by David Crystal Emotional: ProsodyDokumen6 halamanFunctions of Intonation by David Crystal Emotional: ProsodyLera BaliukBelum ada peringkat

- FormllessnessDokumen11 halamanFormllessnessMahmoud Moawad SokarBelum ada peringkat

- A Note On The Linguistic Affinities of Ardhmagadhi PrakritDokumen11 halamanA Note On The Linguistic Affinities of Ardhmagadhi PrakritimmchrBelum ada peringkat

- A Brief Survey of Sanskrit PDFDokumen8 halamanA Brief Survey of Sanskrit PDFARNAB MAJHIBelum ada peringkat

- Sarathi2009 4 Divan e GhalibDokumen5 halamanSarathi2009 4 Divan e Ghalibsudipto917Belum ada peringkat

- Analysis of The Finite Verb Phrases in The Short Stories The Gift of The Magi and Cosmopolite in ADokumen9 halamanAnalysis of The Finite Verb Phrases in The Short Stories The Gift of The Magi and Cosmopolite in ARENA ANGGUNTIA100% (1)

- Indian Theory of TranslationDokumen11 halamanIndian Theory of TranslationManoj Sankaranarayana100% (1)

- Non-Cognitive Tools of TranslationDokumen12 halamanNon-Cognitive Tools of TranslationAnonymous 9hu7fl100% (1)

- Barthes' Textual Analysis of Poe's 'The Facts in the Case of M. ValdemarDokumen4 halamanBarthes' Textual Analysis of Poe's 'The Facts in the Case of M. ValdemarFarooq KhanBelum ada peringkat

- F. Steingass-The Student's English-Arabic Dictionary-Crosby Lockwood and SonDokumen1.276 halamanF. Steingass-The Student's English-Arabic Dictionary-Crosby Lockwood and SonCorina MihaelaBelum ada peringkat

- Urdu Literature - WikipediaDokumen42 halamanUrdu Literature - WikipediaMaliha KhanBelum ada peringkat

- The Literary Culture of Classical Urdu PoetryDokumen40 halamanThe Literary Culture of Classical Urdu PoetryNeetu SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Urdu Love Poetry in The 18th CenturyDokumen29 halamanUrdu Love Poetry in The 18th CenturyPriya Nijhara0% (1)

- Pash - Man and Poet PDFDokumen6 halamanPash - Man and Poet PDFAman MannBelum ada peringkat

- Twilightindelhi00unse PDFDokumen226 halamanTwilightindelhi00unse PDFshalokhanBelum ada peringkat

- Grierson SharadaDokumen33 halamanGrierson SharadaAnonymous n8Y9NkBelum ada peringkat

- IntroductionDokumen13 halamanIntroductionBahare ShirzadBelum ada peringkat

- Panini and Modern+ Linguistics PDFDokumen16 halamanPanini and Modern+ Linguistics PDFSudip HaldarBelum ada peringkat

- Book PahlaviDokumen40 halamanBook PahlaviArmin AmiriBelum ada peringkat

- Transformational Generative Grammar (T.G.G.) : The Linguistic FoundationDokumen23 halamanTransformational Generative Grammar (T.G.G.) : The Linguistic FoundationPrince MajdBelum ada peringkat

- Sindhi LanguageDokumen106 halamanSindhi LanguageJaved RajperBelum ada peringkat

- What Are Adverbial PhrasesDokumen3 halamanWhat Are Adverbial PhrasesPaul Dean MarkBelum ada peringkat

- 2 6 17 357 PDFDokumen3 halaman2 6 17 357 PDFfrielisa frielisaBelum ada peringkat

- Kuvalayamala 2Dokumen14 halamanKuvalayamala 2Priyanka MokkapatiBelum ada peringkat

- Meghaduta With Sanjivani VyakhyaDokumen271 halamanMeghaduta With Sanjivani Vyakhyanvcg10Belum ada peringkat

- Semantic Analysis of Shakespeare's HamletDokumen7 halamanSemantic Analysis of Shakespeare's HamletGeorge PopchevBelum ada peringkat

- Faiz Ahmad FaizDokumen23 halamanFaiz Ahmad FaizIBRAHEEM KHALILBelum ada peringkat

- English-to-Hindustani Dictionary (John Shakespeare, 1849)Dokumen190 halamanEnglish-to-Hindustani Dictionary (John Shakespeare, 1849)Azad QalamdaarBelum ada peringkat

- Basics of Radiation PDFDokumen28 halamanBasics of Radiation PDFCristhian Jeanpierre Cueva AlvaresBelum ada peringkat

- Pata Khazana Paper 1971Dokumen16 halamanPata Khazana Paper 1971Dr. Muhammad Ali DinakhelBelum ada peringkat

- Chaukhandi Tombs: Peculiar Funerary Architecture in Sindh and BaluchistanDokumen207 halamanChaukhandi Tombs: Peculiar Funerary Architecture in Sindh and BaluchistannirvaangBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 1-Principles of TranslationDokumen25 halamanLecture 1-Principles of TranslationRida Wahyuningrum Goeridno DarmantoBelum ada peringkat

- Comparative Analysis of Urdu and English Texts of "Subh-e-Azadi" by Faiz Ahmed FaizDokumen7 halamanComparative Analysis of Urdu and English Texts of "Subh-e-Azadi" by Faiz Ahmed FaizProf. Liaqat Ali MohsinBelum ada peringkat

- BEEC5 Apte V SH Students English Sanskrit Dictionary PDFDokumen484 halamanBEEC5 Apte V SH Students English Sanskrit Dictionary PDFserby108Belum ada peringkat

- Basic Assumptions of GrammarDokumen40 halamanBasic Assumptions of GrammarAnastasia FrankBelum ada peringkat

- Ahmad Faris Al-Shidyaq Leg Over LegDokumen6 halamanAhmad Faris Al-Shidyaq Leg Over Legpajamasefy100% (1)

- Example: Discursive FormationDokumen3 halamanExample: Discursive FormationJasti AppaswamiBelum ada peringkat

- Weinrich LetheDokumen22 halamanWeinrich LetheJimmy Medina100% (1)

- Fables and Parables: From the German of Lessing, Herder, Gellert, Miessner &C, &CDari EverandFables and Parables: From the German of Lessing, Herder, Gellert, Miessner &C, &CBelum ada peringkat

- Fables and Parables: From the German of Lessing, Herder, Gellert, Miessner &C, &CDari EverandFables and Parables: From the German of Lessing, Herder, Gellert, Miessner &C, &CBelum ada peringkat

- Paragraph Development: (1) Illustration and RestatementDokumen8 halamanParagraph Development: (1) Illustration and RestatementYordanos TayeBelum ada peringkat

- William Shakespeare (Editor) - Burton Raffel (Editor) - Othello-Yale University Press (2008) (Z-Lib - Io)Dokumen310 halamanWilliam Shakespeare (Editor) - Burton Raffel (Editor) - Othello-Yale University Press (2008) (Z-Lib - Io)davi2002ramalhoBelum ada peringkat

- FOLKLORE: MAPS & TERRITORIESDokumen5 halamanFOLKLORE: MAPS & TERRITORIESMike McDBelum ada peringkat

- Archer Taylor Method in The History and Interpretation of A Proverb A Place For Everything and Everything in Its PlaceDokumen3 halamanArcher Taylor Method in The History and Interpretation of A Proverb A Place For Everything and Everything in Its PlaceMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- The Characteristic Theology of Herman Melville: Aesthetics, Politics, DuplicityDari EverandThe Characteristic Theology of Herman Melville: Aesthetics, Politics, DuplicityBelum ada peringkat

- Cors GetDokumen114 halamanCors Getrb1931095Belum ada peringkat

- Early Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldDokumen7 halamanEarly Journal Content On JSTOR, Free To Anyone in The WorldjosemonBelum ada peringkat

- Medieval ProverbsDokumen20 halamanMedieval ProverbsJoe Magil100% (1)

- Old AgeDokumen6 halamanOld AgeJustin WatsonBelum ada peringkat

- The Planets Comparative Superlative - 87358Dokumen2 halamanThe Planets Comparative Superlative - 87358Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- The CeltsDokumen2 halamanThe CeltsMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- 01 Life As An Astronaut Free SampleDokumen9 halaman01 Life As An Astronaut Free SampleMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Westminster Abbey 64626Dokumen2 halamanWestminster Abbey 64626Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Englishspeaking Countries Quiz 87612Dokumen5 halamanEnglishspeaking Countries Quiz 87612Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Giving Directions Fun Activities Games 51136Dokumen1 halamanGiving Directions Fun Activities Games 51136Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Giving opinions and views in New Headway IntermediateDokumen3 halamanGiving opinions and views in New Headway IntermediateMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- The Story of England (History Arts Ebook)Dokumen234 halamanThe Story of England (History Arts Ebook)Maria Adam100% (1)

- Adv of Frequency ExercisesDokumen1 halamanAdv of Frequency ExercisesMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Adv of Frequency ExercisesDokumen1 halamanAdv of Frequency ExercisesMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- The Tower of London 64622Dokumen3 halamanThe Tower of London 64622Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- They Emmigrated To The UsaDokumen1 halamanThey Emmigrated To The UsaMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Exam Essay Writing Tips Tests 5595Dokumen1 halamanExam Essay Writing Tips Tests 5595Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- The British Traditions 33475Dokumen1 halamanThe British Traditions 33475Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Test Sumativ A5aDokumen4 halamanTest Sumativ A5aMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

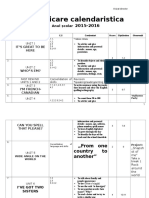

- Planificare Anuala 8Dokumen4 halamanPlanificare Anuala 8Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Test Sumativ A5aDokumen4 halamanTest Sumativ A5aMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Test Initial Engleza A8aDokumen4 halamanTest Initial Engleza A8aMaria Adam100% (1)

- Planificare Anuala A6aDokumen5 halamanPlanificare Anuala A6aMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Test Paper Lesson Plan 6th GradeDokumen5 halamanTest Paper Lesson Plan 6th GradeMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Predictive Test Evaluation 2013-2014 English As Second Foreign Language 6th GradeDokumen3 halamanPredictive Test Evaluation 2013-2014 English As Second Foreign Language 6th GradeMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Planificare Anuala 7Dokumen4 halamanPlanificare Anuala 7Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Guess Who 8 GradeDokumen8 halamanLesson Plan Guess Who 8 GradeMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- 0 Past Perfect ViiDokumen8 halaman0 Past Perfect ViiMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- PLANIFICARE A5A AnualaDokumen8 halamanPLANIFICARE A5A AnualaMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Planificare Anuala A5a 2017Dokumen5 halamanPlanificare Anuala A5a 2017Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Prince Charming, The Tear-BegottenDokumen16 halamanPrince Charming, The Tear-BegottenMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Hildebrandt Proverbial PoetryDokumen717 halamanHildebrandt Proverbial PoetryMaria Adam100% (1)

- Lesson Plan 6Dokumen5 halamanLesson Plan 6Maria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- Ifihadmoney 7 PlanDokumen4 halamanIfihadmoney 7 PlanMaria AdamBelum ada peringkat

- FCP Business Plan Draft Dated April 16Dokumen19 halamanFCP Business Plan Draft Dated April 16api-252010520Belum ada peringkat

- Introduction To World Religion and Belief Systems: Ms. Niña A. Sampaga Subject TeacherDokumen65 halamanIntroduction To World Religion and Belief Systems: Ms. Niña A. Sampaga Subject Teacherniña sampagaBelum ada peringkat

- English For Informatics EngineeringDokumen32 halamanEnglish For Informatics EngineeringDiana Urian100% (1)

- Understanding Risk and Risk ManagementDokumen30 halamanUnderstanding Risk and Risk ManagementSemargarengpetrukbagBelum ada peringkat

- Proforma Invoice5Dokumen2 halamanProforma Invoice5Akansha ChauhanBelum ada peringkat

- Emergency Loan Pawnshop v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 129184, February 28Dokumen3 halamanEmergency Loan Pawnshop v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 129184, February 28Alan Vincent FontanosaBelum ada peringkat

- What Does The Bible Say About Hell?Dokumen12 halamanWhat Does The Bible Say About Hell?revjackhowell100% (2)

- Taiping's History as Malaysia's "City of Everlasting PeaceDokumen6 halamanTaiping's History as Malaysia's "City of Everlasting PeaceIzeliwani Haji IsmailBelum ada peringkat

- PNP Operations & Patrol GuidelinesDokumen8 halamanPNP Operations & Patrol GuidelinesPrince Joshua Bumanglag BSCRIMBelum ada peringkat

- Montaner Vs Sharia District Court - G.R. No. 174975. January 20, 2009Dokumen6 halamanMontaner Vs Sharia District Court - G.R. No. 174975. January 20, 2009Ebbe DyBelum ada peringkat

- 8D6N Europe WonderDokumen2 halaman8D6N Europe WonderEthan ExpressivoBelum ada peringkat

- 30 Chichester PL Apt 62Dokumen4 halaman30 Chichester PL Apt 62Hi TheBelum ada peringkat

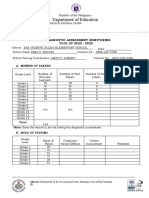

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dokumen3 halamanRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Cultural Awareness Ebook PDFDokumen63 halamanUnderstanding Cultural Awareness Ebook PDFLaros Yudha100% (1)

- Class: 3 LPH First Term English Test Part One: Reading: A/ Comprehension (07 PTS)Dokumen8 halamanClass: 3 LPH First Term English Test Part One: Reading: A/ Comprehension (07 PTS)DjihedBelum ada peringkat

- Land Land Patent - Declaration (19291)Dokumen2 halamanLand Land Patent - Declaration (19291)Seasoned_Sol100% (2)

- The Ten Commandments of Financial FreedomDokumen1 halamanThe Ten Commandments of Financial FreedomhitfaBelum ada peringkat

- Ecommerce Product: Why People Should Buy Your Product?Dokumen3 halamanEcommerce Product: Why People Should Buy Your Product?khanh nguyenBelum ada peringkat

- Al-Qawanin Vol - 2 Sample-9ic1ykDokumen32 halamanAl-Qawanin Vol - 2 Sample-9ic1ykchabouhaBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Talk LetterDokumen1 halamanFinancial Talk LetterShokhidulAmin100% (1)

- Baker Jennifer. - Vault Guide To Education CareersDokumen156 halamanBaker Jennifer. - Vault Guide To Education Careersdaddy baraBelum ada peringkat

- Wires and Cables: Dobaindustrial@ethionet - EtDokumen2 halamanWires and Cables: Dobaindustrial@ethionet - EtCE CERTIFICATEBelum ada peringkat

- UNIT 4 Lesson 1Dokumen36 halamanUNIT 4 Lesson 1Chaos blackBelum ada peringkat

- MBA Capstone Module GuideDokumen25 halamanMBA Capstone Module GuideGennelyn Grace PenaredondoBelum ada peringkat

- Key Ideas of The Modernism in LiteratureDokumen3 halamanKey Ideas of The Modernism in Literaturequlb abbasBelum ada peringkat

- Lawyer Disciplinary CaseDokumen8 halamanLawyer Disciplinary CaseRose De JesusBelum ada peringkat

- New Earth Mining Iron Ore Project AnalysisDokumen2 halamanNew Earth Mining Iron Ore Project AnalysisRandhir Shah100% (1)

- Different Kinds of ObligationsDokumen13 halamanDifferent Kinds of ObligationsDanica QuinacmanBelum ada peringkat

- 320-326 Interest GroupsDokumen2 halaman320-326 Interest GroupsAPGovtPeriod3Belum ada peringkat

- Jffii - Google SearchDokumen2 halamanJffii - Google SearchHAMMAD SHAHBelum ada peringkat