Fiorina Government Essay

Diunggah oleh

darkshadowez0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

434 tayangan7 halamanFlorina Government Essay

Hak Cipta

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniFlorina Government Essay

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

434 tayangan7 halamanFiorina Government Essay

Diunggah oleh

darkshadowezFlorina Government Essay

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 7

12-3

Parties as Problem Solvers

Morris P. Fionna

. . . S . e eo le view parties as self-

PoliticaI parties receive conflicting reviews. om . p p ake essential compro-

. rv ng entities that aenerate unnecessary conjhct, m . l

:-;e i

0

1

. I a- important nation.a

. . difficult and serve as obstac es to :-;o vino .

mise mo1e 'JJ ' h fi aggreaating a van-

bl s Others view party competition as t e means or o .

pro em . . 1 alternatives coordinating action across

ety aj interests, generating po 1cy ' . bl I this

t

d holding elected officials accounta e. n

branches of govern.men ' an ,f' . in

. . l . t' t Morris Fiorina evaluates the role OJ parties

essay poht1ca saen is 11 .

' . ' bl . . the First decade of the new mi enn1u1n.

addressing the nations pro ems in J'

. . - I \vrote an article entitled "The Decline of

T\VENTY-F!VE 'iE.-\RS AGO . 1 . "I that article (henceforth refer-

b1ry American Po incs n

Collective Respons1

1 1

m bility in light

d

DOCR) I uodated the classic arguments for party d h t

ence as , r d . usl deficient. .... LI] note t a

of\vhich the politics of the 1970s looke -dser10 l y el not seen since before the

hesion had droppe tO a ev f

in the 1970s party co . . h d d, erated into a free-for-all o

lt national politics a egen

Civil War. As a resu ' . . . brthelv sacrificed aeneral inter-

. d b . . a in vvtuch paruc1pants 1 , b

unprinc1ple argaininb . . . interests. The unified

. . '. f particularistic consnruency .

esrs m their pursuit

0

. . C re that failed to deal with

f President J1mmv ar r

Democratic government o . fl . ,nd successive energv crises exem-

1 bl

uch as runaway m anon a .,

nariona pro ems s M ot only- had policy failure

f arional politics oreover, n

plif1ed the sorry state o n . . c bers of Conaress increasingly

l

.k 1 b because vormg ior mem b

become more 1 re y, ur 1 ds of1'ncumbents mem-

. . s and persona recor '

reflected the parti.cular1snc acnv1t1e bl their contribution to the fail-

d 1

. tl c ofbeino- held accounta e or h

bers ha it e iear b

1

. h

1

patheticallv resurrected t:: e

1

r In that 1g t sym '

ures of nariona po itrcs. 1 '. 1 e. ntists who advocated more

f 1 midcentury po inca sci

arguments o y to 1 roblems amenable to ,

responsible strong presidents \vere more likely to

solution, unified political part_ y . d \.vhen they rook

. th hallenaes fac1na the country, an

act decisively to meet e c bd th: electorate for ratification or rejec-

their collective performance recor s to d or blame

h d

d dea of \.Vhom to rewar

tion, the voters at least a a goo

1

.,,,Ir VewPcrspective.>on.

;,

>

l

, " - Promoting the Genera! "ve!]are. -

'Parties as Problem So "ers, in Brnokin.gs lostiru'. i

Source: );1orris P. Fionna, d E . M Patashnik (\Vashingron, D.C.:

Alan s Gerber an nc' <

Government Peiformance, eas. - - . . h -iginal have been deleted.

Eion Press, 2006), No::es appearing int e o,

lviorris P. Fiorina 627

Looking back at these essays, the 1980s clearly was the decade of party

responsibility for me. But . . . the prevalence of divided government in the late

twentieth century had raised doubts in my mind about the arguments articu-

lated a decade earlier. These doubts cumulated into a change of position expli-

cated at length in Divided Government and later writings. In brief, as the parties

became more distinct and cohesive during the 1980s, voters seen1ed to sho\.V

little appreciation for the changes. Rather than entrust control of government

to one unified party, i\mericans were increasingly voting to split control of gov-

ernment-at the state as well as the national level. And \Vhether that \vas their

actual goal or not-a matter of continuing debate-polls showed that majori-

ties were happy enough with the situation, whatever political scientists thought

of the supposed programmatic inefficiency and electoral irresponsibility of

divided government. By the early 1990s, I had come to appreciate the elector-

ate's point of view.

Moving from one side of an argument. to the other in a decade suggests that

the protagonist either was wrong earlier or (worse!) wrong later. But there is

another less uncomplimentary possibility-namely, that the shift in stance did

not reflect blatant error in the earlier argument so much as changes in one or

more unrecognized but important empirical premises, ;,vhich vitiate the larger

argument. .... By 1990 I had come to believe that in important respects the par-

ties we \.Vere observing in the contemporary era were different in composition

and behavior from the ones described in the political science literature we had

studied in graduate school. Parties organized to solve the governance problems

of one era do not necessarily operate in the same way as parties organized to

solve the problems of later eras.

This chapter considers the capacity of the contemporary party system to solve

societal problems and meet contemporary challenges. I do so by revisiting

DOCR and reconsidering it against the realities of contemporary politics. I begin

by briefly contrastingl\merican politics in the 1970s and the 2000s.

Politics Then and Now

uv''" reflected the politics of the 1970s, a decade that began with divided gov-

ernment (then still regarded as something of an anomaly), proceeded through

resignations of a vice president and president followed by the brief adminis-

' of an unelected president, then Sa\.V the restoration of the "normal

-unified Democratic government-in 1976, only to see it collapse at the

of the decade in the landslide rejection of a presidency mortally wounded by

,jnternational humiliation, stagflation, alld energy crises. Contemporary critics

628 POLITICAL PARTIES

placed much of the responsibility for "failed" Carter presidency at the feet of

Carter himself-his obsession \:vith detail, his inability to delegate, his political

tin ear, and so forth-but I felt then that the critics were giving insufficient atten-

tion to larger developments and more general circumstances that \vould have

posed serious obstacles for presidents \vho possessed much stronger executive

and political skills than Carter.

Political Conditions in the 1970s

Not only did Jimmy Carter's 1976 victory restore the presidency to the Democrats,

but large Democratic majorities also controlled both the House and Senate. It

seemed that the great era of government activism that had been derailed by the

war in Vietnam \Vould resume. Such \vas not to be. After four years of political

frustration Carter was soundly defeated, the Republicans captured the Senate

\Vith a remarkable gain of twelve seats, and the Democrats lost thirty-three seats

in the House. What happened?

Basically, the country faced a series of new problems, and the Democratic

Parry failed to deal \Vith them in a manner satisfactory to electoral majorities in

the nation as a \vhole and in many states and districts. Gas lines in particular,

and the energy crisis in general, were something ne\v in modern American

experience, as \Vere double-digit inflation and interest rates near 20 percent.

Middle-class tax revolts \Vere a startling development that frightened Democrats

and energized Republicans, a succession of foreign policy setbacks led many

to fear that the United States was ill prepared to deal with new challenges

around the world. In the face of such developments Democratic majorities in

Congress failed to deliver. Indeed, they seemed fixated on old, ineffective solu-

tions like public works spending and trade restrictions. The honeymoon

bet\veen Carter and congressional Democrats ended fairly quickly, and the part-

nership \Vas under strain for most of Carter's administration. Members worked

to protect their constituencies from the negative effects of the ne\.v develop-

ments and worried rnuch less about the fate of Carter or the parry as a \vhole.

A .. s Figure l shows, this \Vas a period of low parry cohesion, and although cross-

parry majorities \.Vere not as con1mon as in the late 1960s, Figure 2 sho\.vs that

they still were common.

The generation of congressiQnal scholars who- contributed to the literature of

the 1950s and 1960s had defended the decentralized Congresses of the period

against the centralizing impulses of presidential scholars and policy wonks. True,

Congress did not move fast or efficiently, nor did it defer to presidential

ship, but most scholars \Vould have characterized this as pragmatic incremental-

ism rather than the "deadlock of democracy." Congress reflected and was

responsive to the heterogeneity of interests in the country.

Tn ;:i vonnP"e:r P-eneration of scholars. however, the failings of the decentralized

80

75

70

65

1'.iiorris P. Fiorina

Figure 1. The Decline and Resurgence of Party in

Government Party Unity, 1954-98

Democrats-'

Year

629

Source: Harold W. Stanley and Richard G N"

(Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2005), Table 5.s.iem1, eds., Vito/ Stat1st1cs on American Politics, 2005-2006

60

50

40

JO

20

10

"'"

/

'o"

0"

"

"p,

e- .. _

\}'

2. The Decline and Resurgence of Party

in Government Party Votes, 1953-98

"'"'

"'"

'II'

""'

0'\,

"/

p,/ , /

.. ;\'\ / "

/

"/

p,'o p,/

0"'

, /

"

p,\5

"

0' p,'O

" "

p,?

" "

,0

630

POLITICAL PARTIES

faced the country, presidents were held for solving these problems,

but incumbent members of Congress seemingly could win reelection by aban-

doning their presidents and parties in favor of protecting parochial constituency

interests. By emphasizing their individual records, members of Congress had

adapted to an era of candidate-centered politics. Historically speaking, they had

far less to gain or lose from the effects of presidential coattails, nor need they .be

very concerned about midterm swings against their president's party. Collecnve

responsibility traditionally provided by the political parties was at a low ebb.

Pluribus was running rampant, leaving unum in the electoral dust.

Political Conditions Now

In retrospect, the trends decried in DOCR had already bottomed out by the

Carter presidency. The cross-party majorities that passed President Reagan's

budget and tax cuts may have obscured the fact, but party unity and party

differences already were on the rise and continued rising in succeeding years

(Figures 1 and 2). In a related development, the electoral advantages accruing

to incumbency already were beginning to recede as national influences in vot-

ing reasserted themselves. And a ne.w breed of congressional leaders emerged

to focus the efforts of their parties in support of or opposition to presidential

proposals. In 1993 President Clinton's initial budget passed without a

Republican vote in the Ho1:ise or Senate, and unified Republican opposinon

contributed greatly to the demise of the administration's signature health

care plan.

And then came 1994, when the Republicans finally had success in an undertak-

ing they had sporadically attempted for a generation-nationalizing the congres-

sional elections. In the 1994 elections, personal opposition to gun control or

various other liberal policies no longer sufficed to save Democrats in conserva-

tive districts whose party label overwhelmed their personal positions. The new

Republican majorities in Congress seized the initiative from President Clinton to

the extent that he was asked at a press conference whether he was "still rele-

vant." When congressional Republicans overreached, Clinton reasserted

evance, beating back Republican attempts to cut entitlement programs and

saddling them with the blame1"or the government shutdowns of 1995-96.

At the time, the Republican attempt to govern as a responsible party srruck

many political scientists as unprecedented in the modern era, but, as Baer and

Bositis pointed out, politics had been moving in that direction for several decades.

Indeed, a great deal of what the 1950 APSA [American Political Science

Association] report called for already had come to pass (Table 1). Now, a decade

Morris P. Fiorina 631

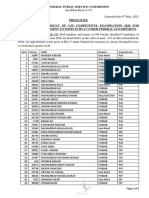

Table 1. APSA Report after Forty Years

Fate of proposal

Democrats Republicans System

Full implementation

13 6 5

Partial implementation

7

5 5

De facto movement

8

9 5

No change

3

10 3

Negative movement

2 3 2

Source: Grossly adapted from Denise Baer and David Bositis, Politics and Linkage in a Democratic Socit ty

(Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, I993), appendix.

later, it is apparent that the Congress elected in 1994 was only the leading edge

of a new period in national politics. Party unity and presidential support among

Republicans hit fifty-year highs the first term of President George w.

Bush, and in 2002 the president pulled off the rare feat ofleading his party to seat

gains in a midterm election. After his reelection in 2004, President Bush spoke in.

terms clearly reminiscent of those used by responsible party theorists. On the

basis of a 51 percent popular majority, he claimed a mandate to make his tax cuts

permanent and transform Social Security. Moreover, early in 2005 when the

president was asked why no one in his administration had been held accountable

for mistakes and miscalculations about Iraq, he replied in words that should have

warmed the hearts of responsible party theorists: 'We had an accountability

moment, and that's called the 2004 election. And the American people listened

to different assessments made about what was taking place in Iraq, and they

looked at the two candidates, and chose me, for which I'm grateful." No presi-

dent in living memory had articulated such clear statements of collective party

responsibility legitimized by electoral victory.

In sum, the collective responsibility DOCR found wanting in the 1970s seems

clearly present in the 2000s. Why, then, am I troubled by the operation of some-

thing I fervently wished for in the 1970s?

' -

The Problems with Today' s Respop.sible Parties

ln 2002 a Republican administration ostensibly committed to free enterprise

endorsed tariffs to protect the U.S. steel industry, a policy condemned by econo-

mists across the ideological spectrum. Also in 2002 Congress passed and President

Bush signed an agricultural subsidy-\>ill that the left-leaning New York Times

632

POLITICAL PARTIES

decried as an "orgy of pandering to special interest groups," the centrist USA.

Today called "a congressional atrocity," and the Economist charac-

terized as "monstrous." In 2003 Congress passed and the president signed a

cial interest-riddled prescription drug plan that \.vas the largest entitlement

program adopted since ivledicare itself in 1965, a fiscal commitment that imme-

diately put the larger Medicare program on a steep slide to\.vard bankruptcy. In

2004 congressional F.epublicans proposed and President Bush supported a con-

stitutional amendment to ban gay marriage, a divisive proposal that had no

chance of passing. his reelection, President Bush declared his highest prior-

ity \.vas to avert a crisis in a Social Security system he insisted \Vas bankrupt, by

establishing a systen

1

of personal accounts, while disinterested observers gener-

ally pronounced the situation far from crisis and in need of relatively moderate

reform-especially compared to Medicare. In 2005 the Republican Congress

passed and President Bush signed a pork-filled transportation bill that contained

6,371 congressional earmarks, forty times as many as contained in a bill vetoed

bv an earlier Republican president in 1987. Meanwhile, at the time of this writing

continue to die in a war of choice launched on the basis of ambiguous

intelligence that appears to have been systematically interpreted to support a

previously adopted position. . r

The orecedina are onlv some of the more note\.vorthy lowlights or public

' b '

policies adopted or proposed under the responsible party government ofZ000-05.

All things considered, if someone \vished to argue that politics in the 1970s \Vas

better than today, I \vould find it hard to rebut them. Why? today's problems

and challenges so much more difficult than those of the 1970s that the decentral-

ized, irresponsible parties of that time would have done an even poorer job of

meeting them than the more responsible parties of today? Or are today's respon-

sible parties operating in a manner that \Vas not anticipated by those of us who

\Vished for more responsible parties? In the remainder of this chapter, I will focus

on the latter possibility.

What Didn't DOCR Anticipate?

\Vith the benefit of hindsight, one potentially negative effect of political

ti ti on bv cohesive differentiafed parties is to raise the stakes of politics. Certainly,

control 'of institutions always is valuable; committee chairs, agenda

control: staff budgets, and numerous other benefits go to the majority. But if

majority control of the House or Senate means relatively little for

because moderate Republicans and Democrats hold the balance of power, which

party formally holds control means less than \Vhen policy is decided within each

lviorris P. Fiorina 633

party caucus. Similarly, the knowledge that the president's program either will

be rubber-stamped by a supportive congressional majority or killed by an oppo-

sition majority makes unified control of all three institutions that much more

valuable. The fact that the parties have been so closely matched in the past

decade makes the competition that much more intense.

With the political sta..lces ratcheted upward, politics naturally becomes more

conflictual. The benefits of winning and the costs of losing both increase.

Informal norms and even formal rules come under pressure as the legislative

majority strives to eliminate obstacles to its agenda. Meanwhile, the minority is

first ignored, then abused. House Democrats under Jim Wright marginalized

House Republicans in the 1980s, and the Republicans have enthusiastically

returned the favor since taking control in 1994. Mean\.vhile Senate Majority

Leader Bill Frist threatens the minority Democrats with the "nuclear option" -a

rules change that effectively eliminates the filibuster on presidential appoint-

ments. In sum, the increasing disparity between majority and minority status

further raises the electoral stakes and makes politics more conflictual.

In retrospect, it is probable that the development of more responsible parties

was a not the only one-that contributed to the rise of the

permanent campaign. With majority status that much more valuable, and

minority status that much more intolerable, the parties are less able to afford a

hiatus bet\veen elections in which governing takes precedence over electioneer-

ing. All else now is subordinated to parry positioning for the next election. Free

trade principles? Forget about them if Pennsylvania and Ohio steel workers are

needed to win the next election. Budget deficits? Ignore them if a budget-busting

prescription drug plan is needed to keep the opposition from scoring points with

senior citizens. Politics al\vays has affected policies, of course, but today the link-

age is closer and stronger than ever before.

A second problem with cohesive parties that offer voters a clear choice is that

may not like clear choices. The APSA report asserted that responsible par-

nes would offer voters "a proper range of choice." But what is "proper"? Voters

may not want a clear choice between repeal of Roe v. Wade and unregulated abor-

tion, between private Social Security accounts and ignori...ng inevitable problems,

benveen launching \vars of choice and ignoring developing threats. Despite

much popular commentary to the contrary, the issue of electorate

as a \vhole are not polarized; voters today remain, as.,,al\vays, generally moderate,

or, at least, ambivalent. But candidates and their parties are polarized, and the

consequence is candidate evaluations and votes that are highly polarized, which

is what we have seen in recent elections.

Even if voters were polarized on issues and wished the parties to offer clear

choices, they would still be dissatisfie-4. if there were more than one issue and the

634 POLITICAL PARTIES

opinion divisions across issues were notthe same. For example, contemporary

Republicans are basically an alliance benveen economic and social conservatives,

and Democrats an alliance benveen economic and social liberals. So, in \vhich

party does son1eone who is an economic conservative and a social liberal belong?

economic liberal and a social conservative? Such people might well prefer

moderate positions on both dimensions to issue packages consisting of one posi-

tion they like a great deal and another they dislike a great deaL

The bottom line is that the majoritariarrism that accompanies responsible parries

may be ill suited for a heterogeneous society. With only one dimension of conflict

a victory by one party can reasonably be interpreted to mean that a majority prefers

its program to that of the other parry. But \\Tith more than one dimension a victory

by one party by no means guarantees majority support for its program(s).

Indeed, . . given variations in voter intensity on different issues, a party can \Vill by

constructing a coalition of the minority position on each issue.

A.merican politics probably appeared to have a simpler and clearer structure

at the time the APSA report \Vas \Vritten. Race \Vas not on the agenda. Social and

cultural issues \Vere largely dormant in the midcentury decades, their impor-

tance di1ninished by the end of immigration in the 1920s, the Great Depression,

and World \Var IL i\. bipartisan consensus surrounded foreign and defense pol-

icy. Under such conditions it is understandable that a midcenrury political

tist could have felt that all the country needed was nvo parties that advocated

alternative economic programs. For example; in 1962 political historian James

McGregor Burns wrote, "It is curious that majoritarian politics has \Von such a

repucation for radicalism in this country. Actually it is moderate politics; it looks

radical only in relation to the snail-like progress of Nladisonian politics. The

Jeffersonian strategy is essentially moderate because it is essentially competitive;

in a homogeneous society it must appeal to the moderate, middle-class

dent voters \vho hold the balance ofpo\ver."

To most contemporary observers the United States looks rather less

neous than it apparently did to observers ofBurns's era. Compared to 1950, our

present situation is ;no re complex with a more elaborate political issue space and

less of a tendency to appeal to the moderate voter, _as we discuss below.

Burns's that majoritarian politics is moderate politics is quite

esting in light of the contemporary discussion of the polarization of i\merican

politics. Although the electorJ:re is not polarized, there is no question that the

political variegated collection of candidates, activists, interest group-'::

spokespersons, and infotainment media-is polarized. And, where \Ve can

sure it \vell, there is little doubt that the political class has become

polarized over the past several decades. Figure 3 illustrates the oft-noted fact that;>,.

moderates have disappeared from Congress: the area of overlap where

rive Democrats and liberal Republicans meet has shrunk to almost nothing,

'

-.-5

::::

'"

LJ

E

'" E

0

ii

LJ

E

::l

z

40

30

20

10

0

-1

Aiorris P. Fiorina

Figure 3. Polarization of Congress since the 1960s

87th House of Representatives (1961-1962)

Democrats

Republicans

-.5

Liberal

106th House of Representatives (1999-2000)

Democrats

Conservative

Republicans

-.5

Source: Keith Poole, http://voteview.com/dwnornin.htm.

Conservative

i--ithas done so at rh .

:2 _ _-. e same Orne as the parties were b

figures like these ofi:e . d . ecom1ng more responsible-

-"'" n are cite as mdicat f

%; Why would polarization ac ors o party responsibility.

JJnde company parry responsibility' Lo . all .

,,;. ed, the APSA report asserted th t "[ ] d d . . gic y it need not.

'.' . a neee clarifi f .

_grself will not cause the parties to _,,,.,. fu canon o parry policy in

':<th- u1.11er more ndame t ll

:,:. ey have in the past." But as I h .. n a y or more sharply than

jj),;-. ave argued elsewhere t d , .

.J-l)Same as the parties described . ct , o ay s parnes are not the

m nu century textbooks. The old ,..li.;::rinr-h,... ... "'

635

636

POLITICAL P:i..RTIES

" . ,, nd "professionals" no

,, d " ofessionals" or punsts a

ben..veen "amateurs an pr 1 1 b use the amateurs have won, or per-

nceptua va ue eca

longer have the same co . t At the time the respon-

1 h rofessionals nO\V are puns s. .

haps more accurate y, t e P . did res on the basis of their

. arties nominated can a .

sible party theorists wrote, p I d or in more competl-

d their connections to party ea ers, , . . d

service to the party an . hen a party \Vas bitterly divide ,

. 1 br Aside from nmes -r...v . .

rive areas, their e ecta 11ty. f didate's suitability. Marena!

. ldon1 a litmus rest o a can .

issue positions were se dominant but civil service,

. 1 f offices, patronage--r...vere '

morivanons-contro o . . l social \velfare programs, and

. . . conflict of mrerest aws, .

public sector uruonizanon, al aterial re-r...vards that once mou-

h ve lessened the person m

1

other developments a . . d .d )ooical motivations are re a-

. . pohncs. To ay, 1 eo b-

vated many of those active m . 1 C didates must have the right set of

. rant than previous y. an ld

tively more impor d f the potential supporters wou pre-

t upport an many o d

issue stances to attrac s ' . ma mushy mo erate.

fer to lose with a pure ideological candidate than to wm W1

h lv s no doubt feel the same.

Some candidates t emse e b . h'ft n party electoral strat-

h e contributed to a as1c s I i .

These developments av . d t ry the conventional w1s-

United States. At mi cen u ,

egy in the contemporary . d 'th political science theory-that

d b

, Burns was in accor Wl h

dom expresse ] d the center to capture t e

. . . duces parties to move towar

nvo-party compennon m f h tury \Ve sa\V a shift to what now

B

. h last decade o t e cen d .

median voter. ut in t e . n the party base- omg

r g strategy of concentrating 0

seems to be the preva1 m d out by core party constituen-

. aximize loyalty an tum

\Vhatever is necessary to m - . f S ote on o-ay marriage was an

. ed forc1n o- o a enate v b

cies. Thus, the c 1 1 Christian base of the Republican

1

. toward the evano-e 1ca

entirely symbo ic gesture . . co- . was a costly signal that the Bush

I

h d nothino- to do \V1th govern1nc, It

Party. t a o . .

administration \Vas on their side. . . . e their vote, only to

. lono-er strive to maximiz

Seemingly, today's parnes no o At one time a ma.ximal victory

s than the other partv.

suffice-to get more vote .b 1 the victors' clain1 that the voters

was desirable because it would add credi 1 d remarks of President

d B the previous y quote

had given them a man ate. 's politicians consider any victory, narrow

Bush indicate, at least some o to ay

or not, a mandate. . . d .d 1 PUes behave differently from the

d f issue acnv1sts an 1 eo

0

o

Parties compose o .

1

. fthe mid-t\ventieth century.

. d the political science iterature o bli

parties that occup1e .cc th of the American pu c;

h ty appealed to a d111erent swa

At midcentury, eac par k d Republicans to middle-class,

. il to blue-collar \VOr ers an f fr

Democrats pnmar y h 1 oc'al groupings were _ar om

Because sue arge s 1

professionals and managers. c h d to tolerate internal heterogene:

. lly the party plat<orm a

homogeneous intema ' bl broad portion of the COllill> >

. . lf d compete across a reasona y .

ity to maintam nse an . Hum hrey- [liberal Democranc

. "[Y]ou cannot ITT.Ve Hubert p

try. /\s Turner put It,

0

A1orris P. Fiorina 637

Senator from Minnesota] a banjo and expect him to carry Kansas. Only a

Democrat who rejects part of the Fair Deal can carry Kansas, and only a

Republican who moderates the Republican platform can carry Massachusetts."

Although both parties contii;.ue to have support in broad social groupings like

blue-collar workers and white-collar professionals, their bases now consist of

much more specifically defined groups. Democrats rely on public-sector unions,

environmentalists, prochoice and other liberal cause groups. Republicans rely on

evangelicals, small business organizations, prolife and other conservative cause

groups. Rather than compromise on a single major issue such as economics, a

process that midcentury political scientists correctly saw as inherently moderat-

ing, parties can now compromise across issues by adding up constituency groups'

most preferred positions on a series of independent issues. Why should conser-

vative mean prolife, low taxes, procapital punishment, and preemptive war, and

liberal mean just the opposite? "What is the underlying principle that ties such

disparate issues together? The underlying principle is political, not logical or

moral. Collections of positions like these happen to be the preferred positions of

groups that now constitute important parts of the party bases.

At one time political scientists saw strong political parties as a means of cori-

trolling interest groups. Parties and groups were viewed as competing ways of

organizing political life. If parties were weak, groups \VOuld fill the vacuum; if

parties were strong, they would harness group efforts in support of more general

party goals. Two decades ago, I was persuaded by this argument, bur time has

proved it suspect. Modern parties and their associated groups now overlap so

closely that it is often hard to make the distinction bet\veen a party activist and

an issue activist. As noted above, the difference between party professionals and

purists does not look nearly so wide as it once did.

Although more speculative, I believe that unbiased information and policy

effectiveness are additional casualties of the preceding developments. The APSA

report asserts, "As a means of achieving responsibility, the clarification of party

policy also tends to keep public debate on a more realistic level, restraining the

inclination of party spokesmen to make unsubstantiated statements and charges."

experience shows just the opposite. Policies are proposed and opposed

r<:lativ<,]v more on the basis of ideology and the demands of the base, and rela

less on the basis of their likelihood of solving problerrlS. Disinformation

and outright lies become common as dissenting voices in each party leave or are

silenced. The most disturbing example comes out or"'congressional passage of the

-.2003 Medicare prescription drug add-on bill. Political superiors threatened to fire

}vfedicare' s chief actuary ifhe informed Congress that the add-on would be 25-50

'percent more costly than the admlnistration publicly claimed. The administra-

6on apparently was willing to lie to members of its own party to assure passage

638

POLITICAL PARTIES

of a bill \Vhose basis \Vas mostly political. More recently, President Bush intro-

duced his campaign to add personal accounts to Social Security by claiming that

Social Security was bankrupt and that personal accounts were a means of restor-

ing the system to fiscal solvency. Although many experts see merit in idea of

personal savings accounts, most agreed that implementing them would increase

Social Security's fiscal deficits in the coming decades. Even greater agreement

surrounded rejection of the claim that Social Security was bankrupt.

politically difficult, straightforward programmatic changes in the retirement

the tax base, or the method of indexing future benefits \.vould make Social

Securitv solvent for as Iona as actuaries can reasonably predict.

, b

Moreover, because parties today focus on their ability to mobilize the already

committed, the importance of performance for voting declines in importance rela-

tive to ideology and political identity. It was telling that in 2004 John Kerry fre-

quently was criticized for not having a plan to end the \.var in Iraq that was

appreciably different from President Bush's. This seems like a new requirement. In

1952 did D\viaht EisenhO\Ver have a specific plan to end the \var in Korea that dif..

b

fered from President 'fruman's? "I \Vill go to Korea" is not exactly a plan. In 1968

did Richard Ni.-xon have a specific plan to end the \.Var in Vietnam that differed from

President Johnson's? A "secret plan" to end the war is not exactly a precise blue-

print that voters could compare to the Johnson policy. Some decades ago voters

apparently felt that an unpopular war was sufficient reason to punish an incum-

bent, regardless of whether the challenger offered a persuasive "exit strategy."

A final consideration relates to the preceding ones. Because today's parties are

composed relatively more of issue activists than of broad demographic group-

inas thev are not as deeply rooted in the mass of the population as was the case

b ' ,

for much of our history. The United States pioneered the mass party, but, as

Steven Schier has argued, in recent decades the parties have practiced a kind of

exclusive politics. The mass-mobilization campaigns that historically character-

ized American elections gave way to the high-tech media campaigns of the late

t\Ventieth century. Voter mobilization by the political parties correspondingly

felL Late-century campaigns increasingly relied on television commercials, and

there is some evidence that such ads demobilize the el_ectorate. In a kind of"back

to the future" development, the nvo most recent presidential elections have st;;:_en

renev.red party effort to get out the vote, with a significant impact, at least in

2004. But n1odern co1nputing capabilities and rich databases enable the parties to

practice a kind of targeted mobilization based on specific issues that \.Vas more

difficult to do in earlier periods. It is not clear that such activities make the parties

more like those of yesteryear, or whether they only reinforce the trends I have

previously discussed. One-third of the voting age population continues to eschew

a party identification, a figure that has not appreciably changed in three decades.

1\1orris P. Fiorina 639

Discussion

In sum, the parties today are far closer to the responsible party model than those

of the 1970s, a development that some of us wished for some decades ago, but it

would be difficult to argue that today's party system is more effective at solvi..J.g

problems than the disorganized decentralized party system that it replaced.

Rather than seek power on the basis of coherent programs, the parties at times

throw fundamental principles to the wind when electoral considerations dictate,

just as the decentralized parties of the mid-twentieth century did. At other times

they hold fast to divisive positions that have only symbolic importance-

President Bush reiterated his support for a constitutional amendment to ban gay

marriage in his 2005 State of the Union fear of alienating ideologi-

cally committed base elements. On issues like Social Security and the \Var in Iraq,

facts are distorted and subordinated to ideology. Mandates for major policy

changes are claimed on the basis of narrow electoral victories.

To be sure, I have painted with a broad brush, and my interpretations of

recent political history may prove as partial and inaccurate as some of those

advanced in DOCR. In particular, I am sensitive to the possibility that unified

Democratic government under present conditions might be significantly differ-

ent from the unified Republican government we have Gilman

argues that the features of responsible parties discussed above are really

Republican features. But even if true, this implies that an earlier generation of

political scientists failed to appreciate that Republican and Democratic respon-

sible party government would be significantly different, let alone identify the

empirical bases for such differences. \Vhat this reconsideration has demonstrated

to me is the difficulty of making broad recommendations to improve American

politics, even when seemingly solid research and argument underlie many of the

component parts, which is the reason I will venture no such recommendations

here. It is possible that this paper is as much a product of its temporal context as

DOCR was. As Aldrich argues, the political parties periodically reinvent them-

selves better to deal with the problems they face. That, in fact, is my hope-that

the next reinvention of the parties results in organizations that are better than

the current-models at dealing \.vith the problems our society faces.

' "

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Don T Let It Bring YOU Down TrebleDokumen1 halamanDon T Let It Bring YOU Down TrebleCacoBelum ada peringkat

- Ferrick v. Spotify Amended Complaint PDFDokumen17 halamanFerrick v. Spotify Amended Complaint PDFMark Jaffe100% (1)

- Gershwin FactsDokumen3 halamanGershwin FactsEmily GriffithsBelum ada peringkat

- The Night They DroveDokumen2 halamanThe Night They DroveSilvia DchBelum ada peringkat

- Beyond The SeaDokumen2 halamanBeyond The SeaRodrigoSanchezFranzaniBelum ada peringkat

- Fables of FaubusDokumen1 halamanFables of FaubusErnest BisongBelum ada peringkat

- The Me For An Imaginary WesternDokumen2 halamanThe Me For An Imaginary WesterngabitegiBelum ada peringkat

- Guided Reading 3 CountercultureDokumen3 halamanGuided Reading 3 CounterculturePeyton McDonald100% (1)

- Swonderful MichaelBreckerDokumen1 halamanSwonderful MichaelBreckerВиталий ЕрмаковBelum ada peringkat

- That's The Way of The WorldDokumen3 halamanThat's The Way of The WorldCatherine Abad - LapitanBelum ada peringkat

- Can't Find My Way Home: IntroDokumen1 halamanCan't Find My Way Home: IntroJan KulpaBelum ada peringkat

- Always On My MindDokumen1 halamanAlways On My MindJosé Miguel FariaBelum ada peringkat

- Zingaro (BB Instruments)Dokumen1 halamanZingaro (BB Instruments)John SurmanBelum ada peringkat

- Led Boots Electric PianoDokumen1 halamanLed Boots Electric Pianoguitarguynick100% (1)

- I Want You She S So HeavyDokumen1 halamanI Want You She S So HeavyLeentje Van ReynBelum ada peringkat

- Play It BackDokumen1 halamanPlay It BackAnleumos Ozedos LeumocliBelum ada peringkat

- Articles Jazz and The New Negro: Harlem'S Intellectuals Wrestle With The Art of The AgeDokumen18 halamanArticles Jazz and The New Negro: Harlem'S Intellectuals Wrestle With The Art of The AgeEdson IkêBelum ada peringkat

- Lakes of PonchrtrainDokumen3 halamanLakes of PonchrtrainFederico PratesiBelum ada peringkat

- Paul Quinichette 'Vice Prez' Tenorsax MasterDokumen27 halamanPaul Quinichette 'Vice Prez' Tenorsax MasterМилан МиловановићBelum ada peringkat

- Clare Fischer - Wikipedia PDFDokumen10 halamanClare Fischer - Wikipedia PDFSilvano AndradeBelum ada peringkat

- Isn't It Romantic? - InstrumentalDokumen1 halamanIsn't It Romantic? - InstrumentalSean AllenBelum ada peringkat

- Ripple - Grateful DeadDokumen1 halamanRipple - Grateful Deadcamp9Belum ada peringkat

- Famous for Fifteen People: The Songs of Momus 1982 - 1995Dari EverandFamous for Fifteen People: The Songs of Momus 1982 - 1995Belum ada peringkat

- Valdez in The CountryDokumen2 halamanValdez in The Countrycristina100% (1)

- WaldElijah TheRagtimeLife HowTheBeatlesDestroyed PDFDokumen11 halamanWaldElijah TheRagtimeLife HowTheBeatlesDestroyed PDFValeria Peñaranda Valda100% (1)

- Traditional Music ResourcesDokumen1 halamanTraditional Music Resourcesmcgg3Belum ada peringkat

- Jim Croce Operator Chord ProgressionDokumen2 halamanJim Croce Operator Chord ProgressionMiguelParraBelum ada peringkat

- Del - Sasser Con TestoDokumen2 halamanDel - Sasser Con TestoViviana NovembreBelum ada peringkat

- I Started A JokeDokumen2 halamanI Started A JokeHendra MulyawanBelum ada peringkat

- A Guide To Cornelius Cardew's Music - Music - The GuardianDokumen4 halamanA Guide To Cornelius Cardew's Music - Music - The Guardianscottvoyles6082Belum ada peringkat

- Brandy (E)Dokumen2 halamanBrandy (E)M StoneBelum ada peringkat

- 70s BrandyDokumen2 halaman70s BrandyMichael SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- Questionable Reimbursements To SticklandDokumen7 halamanQuestionable Reimbursements To SticklandandycargilefortexasBelum ada peringkat

- White Room Bass TabDokumen3 halamanWhite Room Bass TabPeter GoBelum ada peringkat

- Spyro Gyra - Loving You (Intro)Dokumen2 halamanSpyro Gyra - Loving You (Intro)Sanjay ChandrakanthBelum ada peringkat

- I Left My Sugar Standing in The RainDokumen2 halamanI Left My Sugar Standing in The RainFilipe DuarteBelum ada peringkat

- Louis Armstrong Music History LessonDokumen5 halamanLouis Armstrong Music History LessonLaurieBeckBelum ada peringkat

- Pannonica - Chic Corea jazz transcriptionDokumen3 halamanPannonica - Chic Corea jazz transcriptionandyvibeBelum ada peringkat

- Bill Evans: William John Evans (August 16, 1929 - September 15, 1980) WasDokumen18 halamanBill Evans: William John Evans (August 16, 1929 - September 15, 1980) WasbooksfBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis Steely DanDokumen77 halamanThesis Steely DanClaudio AlarconBelum ada peringkat

- Mueller Report To NFL On Ray RiceDokumen96 halamanMueller Report To NFL On Ray RiceBen Doody43% (7)

- Wade in The Water (Lead Sheet)Dokumen1 halamanWade in The Water (Lead Sheet)Wanessa TiburcioBelum ada peringkat

- Cinnamon Girl Chord ChartDokumen2 halamanCinnamon Girl Chord ChartKevinHendrickBelum ada peringkat

- Diva Project Final Paper Revised 12032017Dokumen20 halamanDiva Project Final Paper Revised 12032017Maxthecat789Belum ada peringkat

- I Love The NightlifeDokumen2 halamanI Love The NightlifeRaul CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- Road Trip to Nowhere: Hollywood Encounters the CountercultureDari EverandRoad Trip to Nowhere: Hollywood Encounters the CountercultureBelum ada peringkat

- You Stepped Out of A Dream TriadsDokumen1 halamanYou Stepped Out of A Dream TriadsCarlos HerediaBelum ada peringkat

- Every Little StepDokumen3 halamanEvery Little StepAlan Santoyo LapinelBelum ada peringkat

- Alter EgoDokumen2 halamanAlter EgoAndreasBelum ada peringkat

- Parts-Score - and - Parts - The Cars - My Best Friends GirlDokumen28 halamanParts-Score - and - Parts - The Cars - My Best Friends GirlKeenanBelum ada peringkat

- Takin It To q5 TenorsxDokumen2 halamanTakin It To q5 TenorsxrichardnilesBelum ada peringkat

- Worldsgreatestfakebook IndexDokumen4 halamanWorldsgreatestfakebook IndexPaolino760% (1)

- Ebmaj7 Abm7 Db7 Gm7 C7: 1B 25 Chitarra Cor - NylonDokumen1 halamanEbmaj7 Abm7 Db7 Gm7 C7: 1B 25 Chitarra Cor - NylonFabio IannuzziBelum ada peringkat

- Amelia TranscripcionDokumen3 halamanAmelia TranscripcionQuique Ramírez100% (1)

- House On FireDokumen369 halamanHouse On FireLela100% (3)

- Alphonso Johnson - 1976 - MoonshadowsDokumen3 halamanAlphonso Johnson - 1976 - MoonshadowsNicolobo50% (2)

- 07 Me and Mrs. Jones - StringsDokumen2 halaman07 Me and Mrs. Jones - StringskwhiteBelum ada peringkat

- Culture Dimensions of France in Emily in ParisDokumen3 halamanCulture Dimensions of France in Emily in ParisJulian Safitri100% (1)

- Knowledge Organiser Animal FarmDokumen1 halamanKnowledge Organiser Animal Farm9lisabel9100% (1)

- Crisis of DemoDokumen379 halamanCrisis of DemoKaren BonillaBelum ada peringkat

- BO CSW On Irregular DutyDokumen1 halamanBO CSW On Irregular DutyLMS-NHQBelum ada peringkat

- LAS Politics Q1 Week 1Dokumen4 halamanLAS Politics Q1 Week 1Ricky Canico ArotBelum ada peringkat

- The Election of 1896 The Fall of The Peoples PartyDokumen9 halamanThe Election of 1896 The Fall of The Peoples PartyEdward the BlackBelum ada peringkat

- Formation of Indian National CongressDokumen2 halamanFormation of Indian National CongressRakrik SangmaBelum ada peringkat

- Community Participation in Panchayati Raj Institutions: A Case StudyDokumen13 halamanCommunity Participation in Panchayati Raj Institutions: A Case Studymayuri jadhavBelum ada peringkat

- Political Ideology Liberal Conservative and ModerateDokumen30 halamanPolitical Ideology Liberal Conservative and ModerateAdriane Morriz A Gusabas100% (1)

- 2.A - Brandt Et Al. (2019)Dokumen13 halaman2.A - Brandt Et Al. (2019)Milena IvanovićBelum ada peringkat

- The Long March Through The Institutions How The Left Won The Culture War & What To Do About It - Sidwell MarcDokumen140 halamanThe Long March Through The Institutions How The Left Won The Culture War & What To Do About It - Sidwell MarcFrank SmithBelum ada peringkat

- Upbed 2022 Govt Aided College ListDokumen8 halamanUpbed 2022 Govt Aided College ListraviBelum ada peringkat

- Tirana: Tour Guide To TiranaDokumen4 halamanTirana: Tour Guide To TiranadumbnuggerBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 3 - The Global Interstate System and Contemporary Global GovernanceDokumen50 halamanChapter 3 - The Global Interstate System and Contemporary Global GovernanceBLACK100% (3)

- Francophone Population of AlabamaDokumen2 halamanFrancophone Population of AlabamaineedthisforaschoolprojectBelum ada peringkat

- Peningkatan Kualitas Pembelajaran PKN Di Sekolah Dasar Melalui Model Pengajaran Bermain PeranDokumen9 halamanPeningkatan Kualitas Pembelajaran PKN Di Sekolah Dasar Melalui Model Pengajaran Bermain PeranDewyBelum ada peringkat

- Nationalism Lesson PlanDokumen6 halamanNationalism Lesson Planapi-400922861Belum ada peringkat

- GS-II Governance, Constitution, Polity, Social Justice and International RelationsDokumen4 halamanGS-II Governance, Constitution, Polity, Social Justice and International RelationsAlpesh PanchalBelum ada peringkat

- What'S In: Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDokumen12 halamanWhat'S In: Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsLavender BlueBelum ada peringkat

- History Handout 6 Lecture 6Dokumen8 halamanHistory Handout 6 Lecture 6TusharBelum ada peringkat

- Analyisis Approach Source Strategy General Studies Mains Paper II Vision IasDokumen7 halamanAnalyisis Approach Source Strategy General Studies Mains Paper II Vision IasRana Zafar ArshadBelum ada peringkat

- SENARAI NAMA MENTOR-PROTEGE KHB TINGKATAN 3 2011Dokumen4 halamanSENARAI NAMA MENTOR-PROTEGE KHB TINGKATAN 3 2011Isabel JosephBelum ada peringkat

- 27b - L.U.C.I.D. THE COMPUTER FOR MAZE MIND CONTROL AND THE PROJECT MONARCH FROM NAZI - EgDokumen485 halaman27b - L.U.C.I.D. THE COMPUTER FOR MAZE MIND CONTROL AND THE PROJECT MONARCH FROM NAZI - EgO TΣΑΡΟΣ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΤΙΒΑΡΥΤΗΤΑΣ ΛΙΑΠΗΣ ΠΑΝΑΓΙΩΤΗΣ50% (2)

- Federal Public Service Commission: Merit Roll No. Name Domicile Group/ ServiceDokumen9 halamanFederal Public Service Commission: Merit Roll No. Name Domicile Group/ ServiceMehar Mahmood Idrees100% (4)

- TRS TIMELINE Personal PapersDokumen5 halamanTRS TIMELINE Personal Papersbadsiha naveenBelum ada peringkat

- Reading Have You Ever Watched Any Movies That You Consider ControversialDokumen1 halamanReading Have You Ever Watched Any Movies That You Consider ControversialAnthony Reyes RaveloBelum ada peringkat

- Hoosier Antifeminism in The 1970s Why Indiana Was The Last State To Ratify The Equal Rights AmendmentDokumen20 halamanHoosier Antifeminism in The 1970s Why Indiana Was The Last State To Ratify The Equal Rights Amendmentapi-534691266Belum ada peringkat

- Morga and Rizal views on Philippine cultureDokumen3 halamanMorga and Rizal views on Philippine cultureKaren Joy DaloraBelum ada peringkat

- Sem 1 2023 Revised Routine For Fyugp and FyimpDokumen1 halamanSem 1 2023 Revised Routine For Fyugp and Fyimpdhrubajitb725Belum ada peringkat

- An Inspector Calls Essay GuideDokumen12 halamanAn Inspector Calls Essay GuideDonoghue88% (33)