SPM30 PDF Eng PDF

Diunggah oleh

Valdemar Miguel SilvaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

SPM30 PDF Eng PDF

Diunggah oleh

Valdemar Miguel SilvaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

CASE: SPM-30

DATE: 02/10/06

Mike Harkey prepared this case under the supervision of George Foster, Paul L. and Phyllis Wattis Professor of

Management, as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an

administrative situation.

This case was made possible by the generous support of Mr. John W. Jarve.

Copyright 2006 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved. To order

copies or request permission to reproduce materials, e-mail the Case Writing Office at: cwo@gsb.stanford.edu or

write: Case Writing Office, Stanford Graduate School of Business, 518 Memorial Way, Stanford University,

Stanford, CA 94305-5015. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a

spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

otherwise without the permission of the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

HRJ CAPITAL:

FROM SUPERBOWLS TO SUPERFUNDS

Go see a doctor first.

Advice offered by football great Joe Montana to the rock star Bono on the

announcement that the multi-platinum singer would be starting a venture capital firm.

1

INTRODUCTION

How does success in one line of work translate to another? Are the fundamentals of winning the

same from one stage to the next? Can lightning strike twice? When Ronnie Lott was still in the

National Football League (NFL), he thought he knew the answer. He long had admired a

handful of legendary football players who had become thriving entrepreneurs: Willie Davis (beer

and FM radio businesses), Willie Lanier (securities and investments), and Gale Sayers (computer

supplies). He had also heard his share of cautionary tales about athletes losing their savings on

ill-conceived ventures of all sorts, including real estate schemes, soy futures, and import

operations. He said, Being an entrepreneur is not for everyone; just like not everyone can go

out and play quarterback or safety. The thing about entrepreneurs is that they're not afraid to

fail.

FOUNDERS

Playing Days

Ronnie Lotts football career earned him spots in both the College Football and Professional

Football Halls of Fame, ranking him unarguably as one of the best defensive players of all time

(see Exhibit 1 for an overview of Lotts background). Over the course of 14 seasons in the NFL,

1

Eric Dash, So That's What He's Looking For, The New York Times, July 4, 2004.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 2

his teams won four Super Bowls, and he was named to 10 Pro Bowls. Notwithstanding these

achievements, many of his fans admired him most for the time he had the tip of his finger

amputated during the season after getting it caught in a player's face mask so he would not miss

the rest of the season and playoffs.

Less widely known, Lott had entrepreneurial ambitions that kept him busy off of the playing

field. In 1981, when he was a rookie in the NFL, he launched a video game business by

persuading an acquaintance to let him put a pinball machine in his hotel. When that business

fizzled out, Lott switched to selling calendars and later developed a video business. He also

dabbled in a few restaurant opportunities. In total, his missteps in business were not that unusual

among athletes. Its like playing a game without having a handbook in hand, Lott said.

2

In 1984, he started to learn about the private equity business after meeting John Mumford,

founder and General Partner at Crosspoint Venture Partners, an early-stage venture capital firm

based in Woodside, California. Mumford had been a private equity investor since the early-

1970s and encouraged Lott to consider placing some of his football earnings into venture capital.

Flush with a new contract from the 49ers, Lott put $150,000 into Crosspoints venture fund in

1984. Shortly thereafter, Mumford and his partners invested in companies like Brocade and

Office Club, a retailer of office products for small businesses. Brocade would later have a

successful IPO; Office Club would grow to become the booming Office Depot, and Crosspoints

investors (Lott included) would garner significant financial returns.

Harris Barton, a 64 offensive lineman from Atlanta, Georgia, also had an outstanding football

career (see Exhibit 1 for an overview of Bartons background). He first earned national

attention at the University of North Carolina (UNC), where he was recognized as an All-

American in his first year. In 1987, he joined Lott at the 49ers, becoming the teams first-round

pick (22nd pick overall). In 12 NFL seasons, he was a mainstay of the 49ers offensive line,

helping the team win Super Bowls in 1989, 1990, and 1995. Barton blocked for two Hall of

Fame quarterbacks (Joe Montana and Steve Young) and earned All-Pro honors in two seasons.

During their time as teammates on the 49ers, Lott and Barton were more professional colleagues

than close friends: for one, they played on different sides of the ball (Lott on defense, Barton on

offense). Nevertheless, the huge success of the 49ers franchise in the 1990s brought many

people (e.g., management, coaches, teammates, and fans) closer together. For Lott and Barton, a

mutual interest in the topic of life after football was what ultimately teamed them up. Barton

said:

A lot of NFL players leave the game in their thirties and dont have anything to

do. Ronnie and I were determined that that wasnt going to be the case for us.

We didnt want to just sit on our butts and go fishing or play golf everyday. We

both wanted to do something that would help people out.

Their desire to prepare themselves for life after football was not unique. Throughout the 1990s,

the 49ers organization (e.g., owner Ed DeBartolo and Coach Bill Walsh) strongly encouraged

players to pursue education in all forms. Consequently, some players took MBA classes, and

2

Laura Holson, Portfolio of Champions, The New York Times, February 3, 2001.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 3

others learned about the business of football. Lott and Barton, on the other hand, sought to use

the platform of pro football to build a professional network. Barton said:

Ronnie was the first guy that said to me, Football has been great to you, but you

cant play forever. You should start trying to meet peopleto figure out what

your next career is going to be. He was somebody I greatly admired, so I took

his advice. In pro football, players typically have Tuesdays off. Most NFL guys

dont do anything on their day off: Some play golf; some watch television, and

some lift weights. Ronnies approachwhich I followedwas to use Tuesdays

to take advantage of the opportunities that are out there.

After the success of Lotts investment in Crosspoint, Mumford remained a professional mentor

for Lott, introducing him to a wide-range of professionals. Barton also became a vigorous

networker while still in the NFL, getting to know his share of the business leaders in Silicon

Valley. In 1994, he met a few of the partners at Sequoia Capital, a venture capital firm based in

Menlo Park, California, who offered him the chance to invest in its seventh venture fund. Barton

said:

I got such a big kick out of my investment in Sequoia because everyone was

making a lot of money, and I was also getting a chance to meet the entrepreneurs

that were running Sequoias portfolio companies. What I discovered was that

many of these business peopleat companies like NVIDIA and Brocadewere

also 49er fans. Consequently, I stayed with it; I asked questions, and I kept

meeting peoplepeople like Warren Hellman from Hellman & Friedman and

George Roberts at KKR, who became a mentor for me.

Retirement

When Bartons playing days were ended abruptly because of an injury he suffered early in the

1998 NFL season, he was, of course, extremely dejected.

3

He said, I was sitting at home

feeling sorry for myself. Before long, when Lott learned that his ex-teammate had been

sidelined, he decided to call Barton to talk about his future plans. Lott had been out of NFL

action for a few years and knew what the former lineman was going through. Lott said:

No pro athlete ever wants it to end. When you're finished playing, it's like being a

horse that gets put out to pasture. I remembered what it was like: sitting there by

myself and not having the phone ring, while my teammates were still playing. It

was very difficult. So when I called Harris, I was not surprised to find him down

in the dumps.

The pair agreed to meet at a Palo Alto, CA eatery called the Peninsula Creamery. Lott said:

Harris was still on crutches from his injury when we met for breakfast. We

chatted about what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. I asked him what his

3

During the fourth quarter of a pre-season game against the Miami Dolphins, somebody fell on his leg and snapped

it.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 4

ambitions were. He said he didnt want to go back to business school (he was 35

years old) and that he was still figuring it all out. He then proceeded to tell me

about all of the people he had met when he was a 49er. You would think only a

Joe Montana could have a rolodex like Harris had at the time. He knew

everybody. It was clear that he had worked very hard to get to that point.

What I learned from him was that any athlete could do what he did: He has to

apply himself; he has to go out and work at it; he has to commit time during the

season, and he has to spend time in the off-season building relationships.

Then Harris told me that what he really wanted to do now that his playing days

were over: He said, I want to change mankind.

On the one hand, Lott was taken aback by Bartons bold proclamation. On the other hand, he

was impressed by Bartons passion and track record of accomplishments (both on and off the

field). In the end, Lott proposed a second meeting, this time with Mumford.

BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY

At Crosspoints offices, the NFL retirees talked to Mumford about their desire to get into

business. By the end of the meeting, the idea of creating a fund-of-funds was introduced. A

fund-of-funds is a collection of capital raised for the purpose of investing in other professionally

managed investment pools, like venture capital or leveraged-buyout (LBO) funds.

4

Lott said:

The fund-of-funds concept came up very quickly in that conversation. Mumford

said, You have contacts with all these venture capitalists and people in the legal

community, and they all want to help you start a business. Why dont you go to

them and ask them for an allocationa chance to invest in their funds? Youve

both invested in venture capital funds before out of your own pocket. Instead of

doing that, why dont you raise money for the same purpose?

He was right. We had been able to secure venture capital allocations beforeon

a pretty small scale, mind you. Nevertheless, we both believed we could do that

again, and with Mumfords help, perhaps in a much larger way. Raising a fund,

on the other hand, would be new to both of us. Immediately we began discussing

the idea of reaching out to the high profile athletes we knew as potential investors.

In 1998 and early-1999, our sense was that most athletes didnt know much about

venture capital, but would have loved to have been a part of our earlier

investments in Crosspoint and Sequoia.

It was as simple as that. We agreed that we would raise a small fund, get other

athletes to invest in it, try to get some other people to invest in it, and see if we

could make this thing go. When we left Mumfords office, I knew we couldnt

4

Definition of fund-of-funds: A partnership organized to invest in other partnerships, thus providing the limited

partner investor with added diversification and the ability to invest smaller amounts into a variety of funds.

Thomson Venture Economics, National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2005, pg. 89.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 5

change mankind by doing a fund-of-funds, but I thought perhaps we could help

a few of the guys down at the 49er facility.

Access

By the late-1990s, most top-tier venture capital funds were closed to all but a select group of

exceptionally high net worth individuals and a limited number of institutional investors (e.g.,

foundations, university endowments, and pension funds). Most of these investors made direct

investments into private firms, which required highly specialized knowledge of the private equity

business, deal flow, support staff, and a large pool of capital.

Ultimately, the performance of venture capital has merited the exclusion by which its allocations

were doled out. Overall venture capital returns have consistently out-performed the market. In

1999, rolling five-year returns for venture capital were 47.8 percent, compared to 26.2 percent

for the S&P 500 and 40.2 percent for the NASDAQ (see Exhibit 2 for a comparison of returns).

Further, top quartile venture capital outperformed median returns by over 10 percent for the 30

years from 1969 to 1998 (see Exhibit 3 for top quartile returns). Consequently, the funds that

were proven winnersthose that had consistently performed in the top quartilewere the most

sought after and reserved access for an exclusive club of mostly previous investors.

Another barrier for investors who wanted to participate in venture capital was that most funds

had minimum investment thresholds ($2 million for a $100 million fund and as high as $20

million for much larger funds).

5

In most cases, the minimums were too high for investors to

truly develop a diversified portfolio across a number of venture funds, precluding most investors

(individuals, small pension funds, and university endowments alike) from making direct

investments into private equity firms.

Funds-of-funds

Funds-of-funds were established to solve both problems: access and diversification. Notably,

most funds-of-funds secured allocations to a wide-range of top performing managers and

provided diversification in two ways within an asset class. First, funds-of-funds provided

diversification by the indirect nature of their investments. For example, if a fund-of-funds makes

10 investments in venture capital funds and each of those funds holds 20 portfolio companies, an

investor would then have equity positions in 200 portfolio companies (see Exhibit 4 for an

illustration of the funds-of-funds concept).

Second, funds-of-funds also provided diversification by investing in management teams that had

differing areas of focus: maturity (e.g., early stage vs. later stage), industry expertise (e.g.,

software vs. health care), and geographic exposure (e.g., Silicon Valley vs. India).

5

Typically, investors in private equity funds do not pay their full commitment to the fund up front, for purposes of

minimizing the time such capital sits unspent. Investors typically transfer their committed capital to the fund on an

as-needed basis. When a private equity fund determines it needs some portion of the investors money, it will

make a capital call, a request for transfer of monies with some advance notice (often less than 30 days). Because

of the unfixed timing associated with capital calls, investors are usually asked to maintain a substantial portion of

their capital commitments in assets that can be readily converted to cash.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 6

The first funds-of-funds launched in the early 1970s with less than $100 million under

management. By 1999, commitments to funds-of-funds had ballooned to over $20 billion

worldwide (see Exhibit 5 for a trend of commitments to funds-of-funds). Investors in funds-of-

funds were mostly institutions and high net worth individuals. Some larger funds like Adams

Street Partners also managed their own venture capital funds in order to make direct investments

in companies (see Exhibit 6 for an overview of selected funds).

Funds-of-funds typically received compensation from two sources for their services. First, they

often charged an annual management fee between 0.5 and 1.2 percent of committed capital

through the life of each fund (see Exhibit 7 for more detail on management fees).

6

Second,

funds-of-funds charged a success-based carry on the net profits of the fund (often only after a

certain target or hurdle was met).

7

Comparatively, venture capital firms commanded a premium

over funds-of-funds, taking 2.0 to 3.0 percent or more annually in management fees in addition

to a 20 to 30 percent carry.

START-UP PHASE

Value Proposition

In early-1999, Mumford met with the ex-49ers to help them get their fund-of-funds concept,

which they later named Champion Ventures, off the ground. He reiterated to Lott and Barton

just how fortunate they were to have secured allocations in venture funds in the past. Mumford

told them, My firm doesnt need capital. When we are raising a new fund, we can raise it in

three days. Champion Ventures has got to offer something to the venture capitalistsa unique

value propositionto be able to get their attention. Barton added:

Based on what Mumford told us, we knew we couldnt go to the top-tier venture

capital funds and ask for huge allocations. They just werent going to give it to

us. We also had enough experience to know that youve got to invest with the

best because those are the guys that are going to continue to give you the best

results. From then on, we began operating on the premise that investing (in

venture funds) was a privilege and not a right. Those discussions got us talking

about what Ronnie and I could bring to the table that the average investor could

not.

Lott and Barton came up with the idea of offering their and also their investors celebrity and

salesmanship to venture capital portfolio companies in exchange for the right to invest in top-tier

venture funds. Mumford approved of the concept because he knew that many start-ups needed

help building market awareness for their offerings, particularly in early-1999 when droves of

newly funded consumer Internet companies were competing for attention. In 2000, Jay Hoag, a

managing general partner at TCV, said, A lot of businesses are real consumer focused, and

6

For example, a management team with $40 million in committed capital and a 1.0 percent management fee would

be paid out $400,000 each year.

7

A 10 percent carry (with no hurdle) means that if a $40 million fund-of-funds returned $100 million, then the fund-

of-funds management would retain $6 million (or 10 percent of the $60 million profit). The remainder (after

management fees) would be distributed to investors.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 7

someone like Joe Montana would be a great spokesperson.

8

Mayfield general partner Kevin

Fong added:

9

Were all looking on the margins for any competitive advantage our companies

can get. So whether [the athletes] are helping us recruit because theyre well-

known investors or maybe getting an opportunity to work at one of the companies

themselves, its important. Competition is so great right now [that] any little

thing that pushes you over the edge and helps you land that next great engineer or

salesperson is actually a big, big thing.

Champion promised that they could deliver the venture funds and their portfolio companies

access to Champions stable of athlete investors, in the form of appearances and meet-and-greets

at sporting events, golf outings, company meetings, and corporate events. Barton said:

We developed a pitch to the venture funds that said, We will help you drive sales

(for your portfolio companies). We will help you recruit. We will help you

promote. We will help you with your philanthropic endeavors. Whatever it is;

wherever we can make a difference, we want to help. Instead of giving us some

type of endorsement fee, just give us the opportunity to invest with you. Were

not asking for $50 million: just give us a $5 or $10 million allocation in your next

fund.

Once we had our pitch in place, Mumford set up meetings for us with several

venture funds. Then, Ronnie and I put on our coats and ties, and we walked up

and down Sand Hill Road and met with a dream team of venture funds: Redpoint,

Benchmark, Matrix, Greylock, Accel, and the list goes on. We said to the firms,

If you help us produce a top-tier fund-of-funds, we will assemble a list of all-star

investors of only A-list athletes, and we will educate them about their investments

and connect them with reputable people. Perhaps, they may even get a job out of

it doing promotional or publicity work for one of the portfolio companies.

The concept sold incredibly well up and down Silicon Valley. People loved the

idea and loved being associated with it.

Lott and Barton did not go it alone; they relied heavily on the opinions of Mumford and those in

the venture community in determining with which firms they should be speaking. They also

developed an advisory board to give them counsel (see Exhibit 8 for advisory board members).

A few of the larger endowments (Harvard, Stanford, and Yale) even offered insight into who

were the best funds and why. They quickly learned that the list of clear winners was very short,

and it was the same for everybody.

In 1999, Mumford introduced Lott and Barton to Frank Currie, an attorney with the law firm

Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati, and Jim Atwell, a partner at the accounting firm

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, both of whom helped Champion put the building blocks in place

8

Mike Hofman, Any given start-up, Inc., May 16, 2000, pg. 63.

9

Roy S. Johnson, Playing for big money, Fortune, May 15, 2000, pg. 328.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 8

for the fund.

10

Soon, the team was operating on a new field of play that was comprised of legal

compliance, offering memos, accounting systems, HR infrastructure, and financial reporting.

Fundraising

In 1999, Champion Ventures was successful in securing $39 million of capacity for its first

venture capital fund-of-funds, garnering access to top-tier venture funds like Kleiner Perkins

Caufield & Byers (KPCB) and Benchmark Capital (see Exhibit 9 for a list of sample

investments). Concurrently, Lott and Barton had also begun raising their fund. For its first fund,

Champion required its investors to commit no less than $250,000.

11

For its second fund, the

minimum investment level was raised to $500,000. Barton said:

We told our investors, If you put your money with Mumford, Kevin Fong

(Mayfield), Jay Hoag (Technology Crossover Ventures), Jeff Yang (Redpoint),

and Vinod Khosla (KPCB), you can achieve better diversification in the asset

class (venture capital) than you can get from investing in your neighbors Internet

company. Additionally, over the long haul, venture capital has performed much

better than whatever cockamamie ideas youre coming up with are likely to

perform and better than whatever restaurant deal or car wash business you might

stumble across.

Early in the fundraising process, Lott and Barton focused on selling to financial managers and

people who understood the venture capital industry and Champions value proposition. Pitching

the concept to financial managers proved to be effective because they were trusted by the

athletes and were able to spread the word quickly to a large number of potential investors.

However, the path to raising money was not always easy for the ex-49ers. Lott said:

Early on, we heard, No, from a lot of potential investors. They asked us point

blank what we knew about managing money. They would look at us like, For

the last 14 or 15 years, you were playing football. What do you know about this

arena? We would tell the story about investing with Crosspoint and Sequoia, and

we would have to convince people that we had some experience investing our

own capital.

Converting someone to believe in you can be very difficult, particularly when you

have spent all your life doing something else. I felt like I was a rookie all over

againhaving to create meetings and manufacture opportunities. After being at

such a high level (during my professional football career), I found it hard to feel

like I was starting from scratch. I began to doubt myself.

When we were halfway to raising our first fund, I remember Harris pulling me

aside and saying, Don't worry; we'll get there. Sure enough, we raised the $39

million in no time. Harris was always optimistic, and I was and always have been

somewhat pessimistic in my life. For me, that pessimism is what drives methe

10

Frank Currie later joined the Silicon Valley offices of Davis Polk & Wardwell.

11

Per the capital call terms outlined in Footnote 5, not all of this capital was required to be paid up-front.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 9

fear that you're not going to be successful. On the other side, Harris has always

been the person who has championed the cause, and has said, Just keep

believing. It has been a pretty good balance having those characteristics within

the two of us.

GROWING THE BUSINESS

First Down

Indeed, Champion Ventures charter fund was fully sold within months of Lott and Bartons first

meeting in Palo Alto. Barton was off of crutches, and the pair was moving the ball down the

field. They had been able to assemble a team of celebrity athlete limited partners (LPs) that

would appeal to any sports fan and more than fulfill the promise they had made to the venture

community: a whos who from professional baseball, basketball, football, golf, hockey, and

tennis. One such luminary, Joe Montana, added to the 49er mystique and excitement

surrounding Champion with his investment. The groundswell of support was so favorable that

Lott and Barton had to turn away potential investors.

At the urging of its advisory board in 2000, Champion launched a campaign to raise its second

venture fund-of-funds. Montana offered to become more involved in the firm, joining Lott and

Barton as a managing member. Together, they decided to create a much larger fund than the

first, secure office space (they had been borrowing space until then), and hire a team of

professionals to support the endeavor (see Exhibit 9 for an overview of the 2000 fund). Lott

said:

When we first started out, we didnt know a lot about running a fund or how to do

direct investments into deals. We also didnt know how to do the due diligence

on all these new opportunities that were coming out. Our response to that, as in

football, was to punt; and weve punted a number of times.

Part of punting is about surrounding yourself with the best talent out there. Thats

what we did with the 49ers. We had the best talent; we were paid the best; we

traveled the best; we did everything the right way, and we practiced the hardest.

Then, when it really counted, we were the best. Between 1981 and 1998, the

49ers won at least ten games every yearthat record is unparalleled in sports.

Our consistency proved that it wasnt just a fluke; we were surrounded by the

best.

We took that same philosophy to our company: We made sure we hired top-

notched talent; we have always paid well and taken care of our employees; we

made sure that all our accounting was done properly, and we built a back office

infrastructure when we could have farmed it out to somebody else.

The first executive they brought on board was Jeff Bloom, who had deep roots in the private

equity business as an attorney and CFO (see Exhibit 1 for an overview of his background).

Bloom said:

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 10

Everyone I talked to in the venture business was pretty excited about Champion.

Funds-of-funds typically have a huge pressure to scale. Consequently, most raise

giant funds and then figure out where to invest the money afterwards. The

Champion team approached it from the opposite direction; they flipped the

concept on its head. They said, We dont have any reputation as investors.

Therefore, were going to pre-specify the portfolio and let people know exactly

what theyre getting. Investors are not relying on them down the road to figure

out what to pick. In addition to transparency, these guys also offered a fund

portfolio that most institutional investors could only dream of assembling. When

you put those pieces together, it was a pretty powerful story, and I didnt have a

second thought about joining the team.

In 2000, praise for the start-up fund came in droves. A general partner at one of the participating

venture capital firms added, Any one of us would kill to just invest in Champion. Its

essentially a mutual fund of 13 of the best venture capital firms around. Im not sure the athletes

realize this, but Champion is one of the best investment vehicles on the planet.

12

Indeed, that

sentiment was shared widely in the venture community; many of Champions largest investors

were fund managers. Moreover, institutional investors like Cornell University and the

University of North Carolina had made investments in the second fund, providing even more

validation for Champions model. Not surprisingly, the combination of these factors (world

class athletes, an elite venture portfolio, and institutional support) stirred a lot of media interest,

and Lott and Barton found their way into the pages of the Wall Street Journal, Fortune, and

Business Week.

Getting Sacked

Nevertheless, their luck would soon change. In 2000, $106.1 billion of venture capital was

raised, 81 percent more than in 1999 and 246 percent more than in 1998 (see Exhibit 10 for

detailed information on capital commitments to U.S. venture funds). By 2001, there was an

oversupply of capital chasing a scarce number of quality deals, and the wheels came off of the

venture industry. Barton said:

We invested at absolutely the wrong time in venture capital. It would have been

very easy for a group like ours to fall apart and close up shop. By 2001, most

1999 vintage funds were in really bad shape; some even returned unused capital

to their LPs. Luckily for us, we followed the wisdom of our advisors and invested

in only the best funds. Even so, we went through some pretty tough times when

the market took a downturn.

In particular, Champion wrestled with the challenge of having a pool of relatively

unsophisticated investors. Barton said:

Some of our LPs didnt fully understand the terms of the investment. They would

get divorced or theyd change money management firms, and then they would be

12

Roy S. Johnson, Playing for big money, Fortune, May 15, 2000, pg. 328.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 11

forced to justify meeting their capital call obligations or having money in our fund

at all. For whatever reason, they didnt understand that they had committed to

paying us whenever we called on them and that their money could be locked up

with us for a ten-year period.

13

Additionally, as the market worsened, there was rampant speculation that no venture capital fund

(the top-tier included) with a 1999 or 2000 vintage would produce positive results. Barton said:

The challenge for us then (and it still is) is that if we screw up, its in the New

York Times, Sports Illustrated, everywhere. Thats why we have the most at risk

here; our reputations are on the line. On top of that, were the largest individual

investors in our funds, and we werent even taking a salary, particularly during

the downturn. In a few cases, we did what we thought was the right thing to do:

we gave them their money back.

New Product Offerings

The situation was bleak; Barton and Lott visited a number of portfolio companies (companies in

which the venture funds had invested) that were struggling or were going out of business. No

one in Silicon Valley seemed to want a piece of the venture industry. In 2002, Lott proposed the

idea of raising a fund focused on the leveraged-buyout market, an industry in which funds-of-

funds long had been investing. Barton said, When Ronnie speaks, people listen. Hes a great

leader. He sees where the pucks going. It was his idea to do the LBO fund. The $68 million

fund-of-funds would target the best-of-breed private equity shops, including KKR and Hellman

& Friedman (see Exhibit 11 for an overview of the LBO fund). Barton said:

Everybody was telling us to stay away from the big funds that had been around

for a while. The consensus opinion was to focus on the middle market because of

the poor economic times. Instead, Ronnie and I said we were only going to invest

in the proven winners. That was our model, and we were going to stick with it.

In 2003, while they were raising their third venture capital fund, Lott and Barton struggled to get

a number of their previous investors to participate. Many of the athletes balked at the

opportunity, still skittish over the massive fallout in venture capital. On the other hand, small

institutional investors were expressing a lot of interest in the third fund. Bloom said:

We were at a crossroads. We had to figure out how we were going to raise

additional funds. Athletes were turning out to be a pretty limited market; only a

handful of them make enough money where they could consider this kind of an

investment. Clearly, a more institutional client base was the way to gonot only

because of the deeper pools of capital in that market, but because pension funds

and the like are far more sophisticated (in terms of understanding the cyclical

nature of some of these private investments). However, it was not a market we

knew very well.

13

Champions first fund obligated it to give investors a minimum of 15-days advance notice for capital calls.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 12

In support of Champions evolution to a wider and more institutional focus, the team changed the

company name to HRJ Capital. When their third venture capital fund closed, they had raised

$120 million, $30 million less than their second venture fund. Lott and Barton feared that they

may have reached a ceiling for their venture funds-of-funds. They were at the mercy of the

managers in which they invested; the venture funds controlled the allocations and they were all

cutting fund sizes dramatically.

The good news was that the venture capital firms seemed to be pleased with HRJ. Andy

Rachleff, partner at Benchmark Capital, said, The definition of a great LP to us is someone who

we look forward to seeing at our annual meeting and who is also very supportive. The HRJ team

fits that description. They have been everything that wed hoped they would be. Lott and

Barton spent a lot of their time building relationships with the venture firms. By three measures,

it seemed to be paying off. First, Lott and Barton felt confident that they could secure an

allocation from almost any of the top-tier venture funds. Second, HRJs annual meeting was one

of the best attended corporate events in Silicon Valley, consistently populated by the elite fund

managers. Third, all of the participating funds would agree that the HRJ team was eager to

contribute and readily accessible.

On the other hand, few venture firms were employing the full breadth of value-added services

that HRJ was offering. By 2004, many venture firms had moved away from consumer Internet

investments, and HRJs access to celebrity athletes was not seen as valuable as it was in 1999

and 2000. In the end, fewer connections were made between HRJs athletes and the venture

firms portfolio companies than had been anticipated in the funds early days.

Notwithstanding HRJs challenges in justifying its value proposition, it also had to contend with

the typical growth issues faced by all funds-of-funds. In order to increase the size of its venture

funds-of-funds, HRJ would either have to obtain larger allocations or invest in more venture

funds (i.e., pick more winners) and run the risk of diluting the performance of the fund.

Since securing larger allocations was out of their control and investing in more funds seemed

risky, Lott and Barton opted for a different approach. They resolved to develop a portfolio of

funds-of-funds in multiple asset classes that would appeal to a broader array of institutions and

also help them to scale. Bloom said:

The strategy we settled on was to build boutique-sized funds in a variety of asset

classes, where we could use our relationships to invest in the top ten or so players.

If it turns out that the best venture fund we can build is $120 million, then thats

what it is. The quality of our investments is what matters: we need to be ultra-

premium quality all the way through. Weve proven our worth to these managers.

We feel like were good limited partners. We feel like the business model works.

In 2003, Bloom identified real estate as a viable fund-of-fund opportunity: there were no other

firms targeting it, and the big players (e.g., Broadreach Capital, Fortress Investment Group, and

Shorenstein Group) were in high demand. Bloom was right. When we put together our first

real estate fund-of-funds, investors flocked to it, according to Barton.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 13

Ed Rodden

By 2004, the new strategy was proving to be successful. HRJ had grown to almost $700 million

in assets under management across four classes of funds-of-funds. The minimum threshold for

investment in its venture capital fund-of-funds had been raised to $1 million. Its pool of

investors was no longer just athletes and fund managers; institutions comprised 26 percent of its

overall LP base (see Exhibit 12 for composition of limited partners).

In order to achieve its return objectives, the firm was forced to expand beyond the established

winners and attempt to pick the diamonds in the rough and up-and-coming funds.

Consequently, the investment process for HRJs 2004 venture capital fund-of-funds would

include a formal screen of over 150 funds. Needless to say, analyzing and scrutinizing the

performance of those funds was a considerably different process than the consultative process

HRJ had used to select its investments for its first few funds. Barton said:

Ronnie and I felt it was time to bring in somebody that could help move the firm

in a more institutional manner. Our friend David Pottruck, who was running

Charles Schwab, put us in touch with Ed Rodden. When we met Ed, it was clear

that he understood the dynamics and reputation of the firm and that he would be a

great addition to our team. Even so, we did a tremendous amount of background

checking to ensure he fit with our core values.

In 2005, Rodden became Managing Director of HRJ Capital (see Exhibit 1 for an overview of

his background). A long-time senior executive at Schwab, he had over twenty years of

experience in the financial services industry, including stints at McKinsey and Co. and Chase

Manhattan Bank. Rodden said:

I am one more step along the road to the increasing sophistication and

institutionalization of the firm. The core business model has been in place in

some of our product areas. However, as we look across each of the different

products, there is still work to be done. The institutions are demanding

customized professional support and more robust product offerings.

Barton commented about the program to date:

We want to be the best asset management company in the business. In order to do

so, we have to make money for our investor base. Our strategy is to continue to

provide unique products for our investor base; and to continue to find investors

that like to invest across all of the asset categories that we have. When people

talk about HRJ, its not just Harris, Ronnie, and Joe they talk about anymore.

Now people say, HRJ has a solid team of smart folks up there. No doubt about

it, we are all really pleased with how things are going.

Nevertheless, HRJ Capital was not without its challenges. The move over time to a broader-

based investment portfolio raised the issue of whether the contributions the original managing

team provided as LPs could be sustained over more individual funds. Given the time constraints

already placed on HRJs management in building relationships with a wide array of constituents

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 14

(e.g., fund managers, institutional investors, athletes), HRJ would have to ensure that its core

value proposition could scale. Of course, it would also have to recover from its early miscues

and deliver positive financial results to its investors.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 15

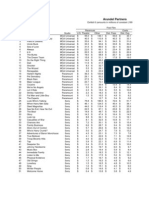

Exhibit 1

Biographies of Selected Executives

Harris Barton (Managing Member)

A veteran of 12 NFL seasons and a first-round draft choice of the San Francisco 49ers in 1987,

Mr. Barton was a two-time NFL All-Pro and was selected as a Pro Bowl starter following the

1993 season. Mr. Barton retired from professional football in 1998. He became a public and

private equity investor during his football career, investing in both publicly traded stocks and

private equity partnerships. The relationships he developed in that process have been

instrumental in building the network of top-tier fund managers available to HRJ Capital. He is a

graduate of the University of North Carolina, where he received a Bachelors degree in Finance.

Ronnie Lott (Managing Member)

Ronnie has been investing in private equity since the early-1980s with firms such as Crosspoint

Venture Partners. Elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2000, Mr. Lott played 14 seasons

in the NFL and enjoyed one of the most celebrated careers of any defensive back in NFL history.

During his ten years with the San Francisco 49ers, the team won four Super Bowls and gained a

reputation as one of the leagues fiercest competitors. He was named to 10 Pro Bowls and was

an eight-time All-Pro selection in three positions as a cornerback, free safety, and strong safety.

Mr. Lott is a graduate of the University of Southern California, where he received a Bachelors

degree in Public Administration.

Joe Montana (Managing Member)

Joe has been a long-time associate of founders Harris Barton and Ronnie Lott through their

professional careers, and became an investor in the first HRJ Capital fund-of-funds in 1999. Mr.

Montana has invested in several projects with principals from Mayfield and Sequoia over the last

decade. One of the greatest quarterbacks in NFL history, Mr. Montana enjoyed an illustrious 16-

year career with the San Francisco 49ers and Kansas City Chiefs. A master of late-game

comebacks, Mr. Montana directed his teams to 31 fourth-quarter come-from-behind wins during

his career. Twice named the NFLs Most Valuable Player, Montana led the 49ers to four Super

Bowl wins, earning three Super Bowl Most Valuable Player awards. He was selected to eight

Pro Bowls and named All-Pro five times. Montana was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame

in 2000. He is a graduate of the University of Notre Dame, where he received a Bachelors

degree in Marketing.

Ed Rodden (Managing Director)

Edward joined HRJ Capital in 2005 as Managing Director where he is responsible for the general

operations of the firm. Previously, he worked at Charles Schwab & Co. for 12 years where he

held a series of senior management positions, including head of corporate strategy, head of retail

marketing, and head of the affluent client business. Prior to joining Schwab, Ed worked at

McKinsey & Co. in their San Francisco office specializing in financial services firms. Edward

began his financial services career at Chase Manhattan Bank working on Asian institutional

relationships in New York, Hong Kong and Bombay. Edward holds a B.A. from Princeton

University's Woodrow Wilson School and received his MBA from Stanford University.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 16

Jeffrey Bloom (Chief Financial Officer)

Jeff joined HRJ Capital in 20001, as Chief Financial Officer. Previously he was Chief Financial

Officer of Storm Ventures, a venture capital firm focusing on the communications and

information technology sector. Prior to his experience in the financial services industry, Jeff was

a partner with the law firm Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati (WSGR), specializing in the

formation and operation of venture capital funds and other private equity vehicles. Prior to

joining WSGR, Bloom practiced as a tax attorney in New York at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton

& Garrison. Jeff received his Bachelors degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

and a joint J.D. and L.L.M. in taxation from the New York University School of Law.

Source: HRJ Capital.

Exhibit 2

Venture Capital vs. Public Market Indexes

Five Year Rolling Average Returns

Five-Year

Period

Ending

Venture

Capital S&P 500 NASDAQ

1990 6.3 9.4 2.8

1991 8.4 11.5 10.9

1992 8.5 12.0 15.4

1993 11.4 10.9 15.3

1994 13.0 5.4 10.6

1995 19.9 13.3 23.0

1996 22.3 12.2 17.1

1997 25.8 17.4 18.3

1998 26.5 21.4 23.1

1999 47.8 26.2 40.2

2000 47.3 16.5 18.6

2001 34.7 9.2 8.6

2002 23.3 (1.9) (3.2)

2003 21.3 (2.0) (1.8)

2004 (1.3) (5.4) (11.8)

Source: Thomson Venture Economics, National Venture Capital Association Yearbook 2005, pg. 15.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 17

Exhibit 3

Venture Capital Top Quartile vs. Median Performance

Year

Upper

Quartile Median Spread

1998 13% 3% 10%

1997 61% 19% 42%

1996 95% 38% 57%

1995 56% 23% 33%

1994 40% 19% 21%

1993 34% 12% 22%

1992 32% 15% 17%

1991 26% 19% 7%

1990 25% 14% 11%

1989 17% 10% 7%

1988 19% 8% 11%

1987 17% 7% 10%

1986 12% 6% 6%

1985 15% 8% 7%

1984 11% 4% 7%

1983 11% 6% 5%

1982 9% 4% 5%

1981 14% 10% 4%

1980 18% 13% 5%

Source: Venture Economics.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 18

Exhibit 4

Illustration of the Funds-of-Funds Concept

HRJ Capital

VC-I

Ronnie

Lott

Harris

Barton

Joe

Montana

John

Mumford

Investor

#4

Investor

#5

Additional

Investors

Benchmark Accel Crosspoint Sequoia Mayfield KPCB Additional

Funds

Investors

Fund-of-Funds

Investment Vehicle

Venture

Capital

Funds

Investee

Companies

Real

Networks

Walmart.com Additional

Companies

Google Martha Stewart

Living

Additional

Companies

HRJ Capital

VC-I

Ronnie

Lott

Harris

Barton

Joe

Montana

John

Mumford

Investor

#4

Investor

#5

Additional

Investors

Benchmark Accel Crosspoint Sequoia Mayfield KPCB Additional

Funds

Investors

Fund-of-Funds

Investment Vehicle

Venture

Capital

Funds

Investee

Companies

Real

Networks

Walmart.com Additional

Companies

Google Martha Stewart

Living

Additional

Companies

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 19

Exhibit 5

Commitments to Funds-of-funds, 1995-2001

($ Billions)

1.7 1.7

8

14

20.2

23.2

13.8

0

5

10

15

20

25

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001

Source: Private Equity Funds-of-Funds State of the Market, Asset Alternatives Research Report, 2

nd

edition, 2002,

p. 24.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 20

Exhibit 6

Overview of Selected Funds-of-Funds

Adams Street Partners

Adams Street Partners, an industry pioneer in partnership fund-of-funds investing, created its

first fund-of-funds offering in the late 1970's.

Adams Street Partners' direct investment team provides venture capital to growth and

development-stage information technology, life sciences and business service firms primarily

based in the United States. The direct investment team has invested over $400 million in 165

companies over the last 30 years.

Source: www.adamsstreetpartners.com

Commonfund

Founded in 1971, Commonfunds mission is to enhance the financial resources of nonprofit

institutions and to help them improve investment management practices. On its first day of

operations in 1971, a total of 63 endowments had invested $72 million in Commonfund. The

Commonfund organization offers its investment funds and services to qualifying nonprofit

organizations, which includes educational institutions, foundations, health care organizations,

and other mission-based and public benefit nonprofits and their pension plans. As of June 30,

2005, its organization had managed approximately $35 billion on behalf of clients. It serves over

1,600 clients, including funds for 72 of the nations top 100 educational endowments, as well as

many of the countrys top foundations and healthcare organizations.

Source: www.commonfund.org

FLAG Capital Management, LLC

Founded in November 1994, FLAG Capital Management, LLC manages twelve limited

partnerships. Through these partnerships qualified individuals and families as well as their trusts

and affiliated foundations invest in a diversified portfolio of high-quality venture and private

equity funds. Sample partnerships include:

- FOX Venture Partners, L.P.: a $107 million partnership, formed in 1995, investing in

leading venture capital funds.

- FLAG Venture Partners II, L.P.: a $210 million partnership, formed in 1997, investing in

leading venture capital funds.

- FLAG Venture Partners III, L.P.: a $325 million partnership, formed in 1999, investing in

leading venture capital funds.

- FLAG Venture Partners IV, L.P.: a $552.5 million partnership, formed in 2000, investing in

leading venture capital funds.

- FLAG Venture Partners V, L.P.: a $375 million partnership, formed in 2003, investing in the

successor funds of most of the fund managers included in the FVP Funds portfolio.

- FLAG Private Equity I, L.P.: a $215 million partnership, formed in 2000, investing in a

diversified portfolio of top-tier private equity funds that possess a demonstrated ability to

generate premium returns by building value in portfolio companies post-investment.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 21

- FLAG Private Equity II, L.P.: a $400 million partnership, formed in 2003, investing in a

diversified portfolio of top-tier private equity funds that possess a demonstrated ability to

generate premium returns by building value in portfolio companies post-investment.

Source: www.flagcapital.com

HarbourVest Partners, LLC

The firm's clients include more than 240 pension funds, endowments, foundations, and financial

institutions from the U.S., Europe, Canada, Australia, and Japan. During its 20-year history of

investing, the HarbourVest team has committed $10.8 billion to over 200 managers of private

equity funds on a primary basis, completed $3.4 billion in 460 purchases of secondary

partnership interests, and invested $2.2 billion directly in operating companies.

Since 1982, the management of HarbourVest has formed seven major investment programs to

invest in the United States, the most recent being HarbourVest Partners VII, a $4.4 billion

investment program formed in 2002 to invest in venture, buyout, and mezzanine opportunities.

The management team is also responsible for forming four investment programs focused

exclusively on making private equity investments outside the United States. HarbourVest

International Private Equity Partners IV was formed in 2002 with $2.8 billion of capital,

including $2.4 billion for partnership investments and $375.0 million for direct investments.

Source: www.harbourvest.com

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 22

Exhibit 7

Management Fees Among Funds-of-Funds Managers

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

0.55% or less 0.56% - 0.75% 0.76% - 1.0% 1.01% - 1.25% 2.0% or more

Management Fee Range

P

e

r

c

e

n

t

o

f

F

i

r

m

s

C

h

a

r

g

i

n

g

1999

2001

Source: Private Equity Funds-of-Funds State of the Market, Asset Alternatives Research Report, 2

nd

edition, 2002,

p. 56.

Exhibit 8

HRJ Capitals Advisory Board Members

(As of January 2005)

- Jonathan Axelrod: Head of Venture Services, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati

- Kevin Fong: General Partner, Mayfield Funds

- Jay Hoag: General Partner, Technology Crossover Ventures

- Dick Kramlich: General Partner, New Enterprise Associates

- John Mumford: General Partner, Crosspoint Venture Partners

Source: HRJ Capital

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 23

Exhibit 9

HRJ Capital Venture Capital Investments

HRJ Capital VC I 1999

Fund Size: $39 million

Sample investments

- Accel Internet Fund III

- Benchmark Capital Partners IV

- Crosspoint Venture Partners 2000Q

- Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers IX-A

- Mayfield X

- Redpoint Technology Partners I

- Sequoia Capital IX

HRJ Capital VC II 2000

Fund Size: $157 million

Sample investments

- Accel VIII

- Benchmark Europe I

- Crosspoint Venture Partners Late Stage 2000

- Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers X-A

- Mayfield XI

- Redpoint Ventures II

- Sequoia Capital X

HRJ Capital VC III 2003

Fund Size: $120 million

Sample investments

- Benchmark Capital Partners V

- Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers XI

- Mayfield XIII

- Mohr Davidow Ventures VIII

- Redpoint Ventures II

- Sequoia Capital XI

- Technology Crossover Ventures V

HRJ Capital VC IV 2004

Target Fund Size: $150 million

Target Exposure:

- 60 percent: Core/Established Managers, e.g., Accel IX, August Capital IV

- 30 percent: Sector Focused Funds, e.g., Sanderling VI (Healthcare/Life Sciences)

- 10 percent: Emerging Managers, e.g., Ignition Partners

Source: HRJ Capital

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 24

Exhibit 10

Capital Commitments to U.S. Venture Funds

1990 to 2004 ($ Billions)

3.4

2.1

5.3

4.1

8.8

10.2

11.6

19.8

30.7

58.6

106.1

38.0

9.0

11.5

18.2

-

20.0

40.0

60.0

80.0

100.0

120.0

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004

Source: Thomson Venture Economics.

HRJ Capital SPM-30

p. 25

Exhibit 11

Overview of Other HRJ Capital Funds*

Growth Capital Fund

- GC I (2002): $68 million

- Representative Managers: Bain Capital, Blackstone Group, Hellman & Friedman, KKR,

Texas Pacific Group

Real Estate Funds

- RE I (2003): $75 million

- RE II (2004): $70 million

- Representative Managers: Blackacre Capital, Broadreach Capital, Fortress Investment

Group, Shorenstein Group

Hedge Funds

- Olympius Capital Hedge Funds: $184 million

- Representative Managers: Caxton Associates, Citadel, D.E. Shaw, Duquesne Capital, Tudor

Investment Corporation

* Other refers to funds not in the venture capital fund-of-fund class.

Exhibit 12

HRJ Capitals Investor Base

(As of January 2005)

Composition of Limited Partners

- 26 percent: endowments/foundations

- 16 percent: private equity managers

- 16 percent: current/former CEOs

- 14 percent: high net worth advisors

- 12 percent: athletes/sports figures

Sample of institutional investors

- Government of Singapore

- Cornell University

- University of North Carolina

- University of Norte Dame

- Macalester College

- Cambridge Associates

- Callan Associates

- Wainwright Investment Council

Source: HRJ Capital

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Vault-Finance Practice GuideDokumen126 halamanVault-Finance Practice GuideMohit Sharma100% (1)

- Vault Guide To Finance Interviews - 7th EditionDokumen166 halamanVault Guide To Finance Interviews - 7th Editionterry34280Belum ada peringkat

- EFVCDokumen11 halamanEFVCValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- PortfolioDokumen2 halamanPortfolioValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Hertz QuestionsDokumen1 halamanHertz QuestionsValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Q7 CorningDokumen16 halamanQ7 CorningValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Marriott Case WACC AnalysisDokumen3 halamanMarriott Case WACC AnalysisNaman SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Corning CaseDokumen1 halamanCorning CaseValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- DivestituresDokumen24 halamanDivestituresValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Corning CaseDokumen10 halamanCorning CaseValdemar Miguel Silva100% (1)

- Bloomberg and Final Remarks JuntoDokumen2 halamanBloomberg and Final Remarks JuntoValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Sealed Air CorporationDokumen4 halamanSealed Air CorporationValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- RAs Part of Problem or SolutionDokumen31 halamanRAs Part of Problem or SolutionViktoria JurkBelum ada peringkat

- Bloomberg VaR MethodologyDokumen15 halamanBloomberg VaR MethodologyMahmoud_nazari2007Belum ada peringkat

- 5 Year Yields Orange CaseDokumen7 halaman5 Year Yields Orange CaseValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- ArundelDokumen11 halamanArundelEduardo MiraBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Management Formula SheetDokumen1 halamanRisk Management Formula SheetValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Case OrangeDokumen7 halamanCase OrangeValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Sec1 Group6 Arundel Partner FinalDokumen18 halamanSec1 Group6 Arundel Partner Finalseth_tolevBelum ada peringkat

- SPs New Capital Weekly Update 050212Dokumen13 halamanSPs New Capital Weekly Update 050212KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Ms&e444 2012Dokumen44 halamanMs&e444 2012Valdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Master Assignment Wouter Van Heeswijk (Final)Dokumen174 halamanMaster Assignment Wouter Van Heeswijk (Final)Valdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Black ScholesDokumen1 halamanBlack ScholesValdemar Miguel Silva100% (1)

- Martin Smith PDFDokumen1 halamanMartin Smith PDFValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Arundel Good SequelsDokumen2 halamanArundel Good SequelsValdemar Miguel SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Title-Hoarding Area of Specialisation - Social-Economic OffencesDokumen29 halamanTitle-Hoarding Area of Specialisation - Social-Economic OffencesAmiya Bhushan SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Citigroup Credit Suisse J.P. Morgan Morgan Stanley Standard Chartered BankDokumen5 halamanCitigroup Credit Suisse J.P. Morgan Morgan Stanley Standard Chartered BankhjsfdrBelum ada peringkat

- Quantitative TradingDokumen34 halamanQuantitative TradingNikhitha PaiBelum ada peringkat

- New 301 Presentation-2Dokumen26 halamanNew 301 Presentation-2api-636032198Belum ada peringkat

- Corporate and Retail BankingDokumen13 halamanCorporate and Retail Bankingbipin kumarBelum ada peringkat

- PSO Sample Report Spring 2022Dokumen1.002 halamanPSO Sample Report Spring 2022Mubeen AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- Questions and ProblemsDokumen25 halamanQuestions and ProblemsLinh LinhBelum ada peringkat

- 604f340b1ee7d20024a3f30d 1615803723 ACC 124 - Week 8 9 - ULObDokumen15 halaman604f340b1ee7d20024a3f30d 1615803723 ACC 124 - Week 8 9 - ULObFrancine Thea M. LantayaBelum ada peringkat

- Italian Asset Gatherers 2017-06-12Dokumen13 halamanItalian Asset Gatherers 2017-06-12luisa_bagnoliBelum ada peringkat

- Invest (Essay)Dokumen2 halamanInvest (Essay)Jesika NursudindaBelum ada peringkat

- Eurozone Group 4Dokumen36 halamanEurozone Group 4NhiHoangBelum ada peringkat

- TechAnalysis InvestopediaDokumen14 halamanTechAnalysis InvestopediaCristian FilipBelum ada peringkat

- Dividend Decisions: Learning OutcomesDokumen35 halamanDividend Decisions: Learning OutcomesAmir Sadeeq100% (1)

- Forex Study Material PDFDokumen48 halamanForex Study Material PDFGaurav SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- Step 1: Analysis of The Subsidiary's Net AssetsDokumen10 halamanStep 1: Analysis of The Subsidiary's Net AssetsJulie Mae Caling MalitBelum ada peringkat

- Capital StructureDokumen42 halamanCapital Structurevarsha raichalBelum ada peringkat

- Shankbook Final RedDokumen64 halamanShankbook Final Redvivek mittalBelum ada peringkat

- Project On Mutual FundDokumen95 halamanProject On Mutual FundMadhusudana p nBelum ada peringkat

- CVDokumen323 halamanCVArlei EvaristoBelum ada peringkat

- Money and Financial Markets: PD Dr. M. Pasche Friedrich Schiller University JenaDokumen65 halamanMoney and Financial Markets: PD Dr. M. Pasche Friedrich Schiller University JenaMuhammad KashifBelum ada peringkat

- Imperial Finance Summer CourseDokumen5 halamanImperial Finance Summer CourseMatthewBelum ada peringkat

- PFRS 9, Paragraph 4.1.2, Provides That A Financial Asset Shall MeasuredDokumen3 halamanPFRS 9, Paragraph 4.1.2, Provides That A Financial Asset Shall MeasuredSwai RosendeBelum ada peringkat

- Prasun Patel - Banking & FinanceDokumen3 halamanPrasun Patel - Banking & FinanceGhanshyam NfsBelum ada peringkat

- Capital Investment AppraisalDokumen41 halamanCapital Investment Appraisalbookabdi1Belum ada peringkat

- MC Investor Presentation VF Q3 23Dokumen24 halamanMC Investor Presentation VF Q3 23l91179909Belum ada peringkat

- Proforma Income StatementDokumen20 halamanProforma Income StatementEnp Gus AgostoBelum ada peringkat

- A Trader's Guide To Use FractalsDokumen6 halamanA Trader's Guide To Use Fractalsuser_in67% (3)

- Practice Test 25 Questions Time: 10.45am To 11.30am: Archisman Dhar Date: 07.05.2016Dokumen7 halamanPractice Test 25 Questions Time: 10.45am To 11.30am: Archisman Dhar Date: 07.05.2016Bitan BanerjeeBelum ada peringkat

- Hec 1Dokumen2 halamanHec 1Allan Mark Ong100% (1)