Advanced Economy Monetary Policy and Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) by Jerome H. Powell

Diunggah oleh

Eduardo PetazzeHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Advanced Economy Monetary Policy and Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) by Jerome H. Powell

Diunggah oleh

Eduardo PetazzeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Advanced Economy Monetary Policy and Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) by Jerome H.

Powell

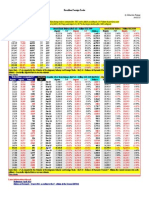

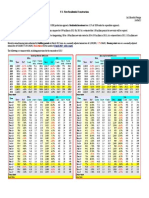

Full S eec! d"# $% ages E&tract ... In my remarks today, I will discuss the extent to which monetary policy in the advanced economies--and in the United States in particular--has contributed to changes in emerging market capital flows and asset prices, and I will place this discussion in a broader context of economic and financial linkages among economies. I will also address the risks that E Es may face from the eventual normali!ation of monetary policy in the advanced economies. ... "hile a great deal of attention has focused on unconventional policy actions, especially asset purchases, these policies appear to affect financial conditions and the real economy in much the same way as conventional interest rate policy. Indeed, recent research suggests that ad#ustments in policy rates and unconventional policies have similar cross-border effects on asset prices and economic outcomes$ If that is so, then the overall stance of policy accommodation matters more here than the particular form of easing oreover, neither conventional nor unconventional monetary policy actions are shocks that come out of the blue. Instead, they are the policies undertaken by central banks to offset the adverse shocks that have restrained our economies. %hus, any spillovers from monetary policy actions must be evaluated against the conse&uences of failing to respond to these adverse shocks. In a world of global trade and integrated capital markets, it is natural for economic and financial shocks and policy actions to be transmitted across borders. Spillovers from advanced-economy monetary policies are to be expected. In theory, when advanced economies ease monetary policy in response to a contractionary shock, their interest rates will decline, prompting investors to rebalance their portfolios toward higheryielding assets. Some of this rebalancing will occur domestically, but some investment will also move abroad, resulting in capital flows to E Es. In response, E E currencies should tend to appreciate against those of the advanced economies, and E E asset prices should rise. 'onversely, a tightening of advanced economy monetary policy in response to a stronger economy should lead these movements to reverse$ that is, tightening should reduce capital flows to E Es and diminish upward pressure on E E currencies and asset prices. (re these basic relationships apparent in the data) %he left side of chart * shows an index of E E local-currency sovereign bond yields along with a roughly similar maturity U.S. %reasury yield. %he line on the right is the differential between the two, plotted against net inflows of private capital to a selection of E Es, shown by the bars. If interest rates were the main driver of capital flows, these two series ought to move in a similar fashion. (t times, this is indeed the case+ ,rom mid--../ to early -.**, the interest rate differential and E E capital inflows rose together. 0ut the overall relationship is not particularly tight. In early -..1, capital flows to E Es were &uite strong even with a low interest rate differential. (nd in mid--.**, capital inflows stepped down even as the interest rate differential remained elevated. (s I will discuss in a moment, the lack of a tight relationship between capital flows and interest rates suggests that other factors also have been important. ,irst, many factors affect capital flows to E Es, not #ust the stance of advanced economy monetary policy. 2ifferences in growth prospects across countries and the associated differences in expected investment returns are important factors 'hart - shows the growth rate of real 324 for E Es and advanced economies. 3iven their stage of development and demographic profile, E Es should grow faster than advanced economies on a trend basis. (s shown by the line in the right panel, E E growth has, in fact, consistently outpaced that of the advanced economies. In addition, the bounceback of the E Es from the global financial crisis widened this differential even more, although the gap has diminished more recently as growth in the E Es has slowed. oreover, investing in E Es has become more attractive as many E Es have improved their macroeconomic policies and institutional frameworks over recent decades$ growth differentials may partly be reflecting these improvements. (s is evident in the right-hand chart, the relationship between the growth differential and capital inflows to E Es seems to be &uite strong. In particular, the rise in capital flows following the global financial crisis coincided with stronger relative growth performance in E Es. (nd in -.**, capital inflows diminished along with the growth differential.

(nother key driver of E E capital flows is global attitude toward risk. Swings in sentiment between 5risk-on5 and 5risk-off5 have led investors to reposition across asset classes, resulting in corresponding movements in capital flows. Indeed, as shown in chart 6, the most common measure of uncertainty and the market price of volatility is strongly correlated with net inflows into E Es. (lthough the causes of movements in global risk sentiment are uncertain, the ebb and flow of potential crises and policy responses, such as we experienced during the European crisis, are clearly important. 7f course, movements in risk sentiment may not be fully independent of monetary policy. (n interesting line of research has begun to consider how changes in monetary policy itself may affect risk sentiment. ,or example, some studies indicate that an easing of U.S. monetary policy tends to lower volatility, increase leverage of financial intermediaries, and boost E E capital inflows and currencies.

( second point to bear in mind when assessing monetary policy spillovers is that expansionary policies in the advanced economies are not beggarthy-neighbor$ in other words, they do not undermine exports from E Es. In recent decades, some E Es have successfully pursued an exportled growth strategy, and policymakers in those economies have sometimes expressed concern that their exports will be unduly restrained as accommodative policies in the advanced economies lead their currencies to appreciate. 8owever, as shown in chart 9, although E E currencies bounced back from their lows during the global financial crisis--when global investors fled from assets they perceived to be risky--for many E Es real exchange rates have moved sideways or have even declined over the past two years. Some of this weakness may reflect the foreign exchange market intervention and capital controls that policymakers used to staunch the rise in their currencies. 0ut even if advanced economy monetary policies were to put upward pressure on E E currencies, the conse&uent drag on their exports must be weighed against the positive effects of stronger demand in the advanced economies. (ccording to simulations of the ,ederal :eserve 0oard;s econometric models of the global economy, these two effects roughly offset each other, suggesting that accommodative monetary policies in the advanced economies have not reduced output and exports in the E Es. Indeed, this view seems to be supported by recent experience, as the U.S. current account balance has remained fairly stable since the end of the global financial crisis. 7ver the longer run, advanced economy policy actions that strengthen global growth and global trade will benefit the E Es as well.

( particularly important consideration regarding spillovers from accommodative monetary policies in the advanced economies is the extent to which such policies contribute to financial stability risks in the E Es. 0ecause many E Es have financial sectors that are relatively small, large capital inflows may foster asset price bubbles and a too-rapid expansion of credit. %hese are serious concerns, irrespective of the relative importance of monetary policies in the advanced economies in driving these flows. "hile the picture is a mixed one and some markets show signs of froth, indicators of financial stability do not seem to show widespread imbalances. ,or example, E E e&uity prices, shown in chart <, plunged during the global financial crisis, rebounded thereafter, but then generally flattened out or even declined. %here are exceptions, of course, such as Indonesia, whose stock market soared until earlier this year. 0ut in aggregate, E E stock prices remain below their pre-crisis peak, whereas the S=4 <.. is well above its own pre-crisis peak.

'hart > portrays the rise in credit to the domestic nonfinancial private sector as a share of 324 from its pre-crisis level. ,or some E Es, the rise in credit does not seem out of line with historical trends, but some economies have experienced potentially worrisome increases. 'redit growth in 'hina is particularly noteworthy, but this does not seem to be the result of accommodative monetary policies in the advanced economies. uch of the rise took place in the aftermath of the crisis, in large part reflecting policy-driven stimulus to support economic recovery. In addition, 'hina;s relatively closed capital account limits the extent to which domestic credit conditions are influenced by developments abroad, including changes in advanced economy monetary policy. Increases in credit in some other economies, notably 0ra!il, have also been driven to a significant degree by policy actions to support aggregate demand. (nd, of course, E Es have policy tools to limit the expansion of credit.

(nother area of potential concern is excessive valuations in property markets.'hart 1 displays inflation-ad#usted house prices for several (sian economies. %he most striking increases have occurred in 8ong ?ong, which, through its open capital account and essentially fixed exchange rate, is tied most directly to U.S. financial conditions. 7f course, the degree of 8ong ?ong;s exposure to U.S. financial conditions is a policy choice, and other factors have also contributed to the run-up in its property prices. 8ouse prices have also resumed their rise in 'hina. 0ut, as with credit growth, this rise seems to reflect domestic developments as opposed to spillovers from global financial conditions.

In light of these potential financial stability concerns, it is encouraging that E E policymakers have devoted substantial effort since the (sian financial crisis of the late *//.s to bolster the resilience of their banking systems. 0anks in many E Es have robust earnings and solid capital buffers. 'ompared with past experience, emerging market banking systems also generally en#oy improved management and a proactive approach by authorities to mitigate risks. @evertheless, in an environment of volatile global markets, regulators should guard against the buildup of vulnerabilities, such as excessive dependence on wholesale and external funding, declining asset &uality, and foreign currency mismatches. %o summari!e my discussion so far, E Es clearly face challenges from volatile capital flows and the attendant moves in asset prices. (ccommodative monetary policies in the advanced economies have likely contributed to some of these flow and price pressures, and may also have contributed to the buildup of some financial vulnerabilities in certain emerging markets. %hat said, other factors appear to have been even more important. oreover, expansionary monetary policies in the advanced economies have supported global growth to the benefit of advanced and emerging economies alike. ........

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- China - Price IndicesDokumen1 halamanChina - Price IndicesEduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- WTI Spot PriceDokumen4 halamanWTI Spot PriceEduardo Petazze100% (1)

- México, PBI 2015Dokumen1 halamanMéxico, PBI 2015Eduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- Retail Sales in The UKDokumen1 halamanRetail Sales in The UKEduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- Brazilian Foreign TradeDokumen1 halamanBrazilian Foreign TradeEduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- U.S. New Residential ConstructionDokumen1 halamanU.S. New Residential ConstructionEduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- Euro Area - Industrial Production IndexDokumen1 halamanEuro Area - Industrial Production IndexEduardo PetazzeBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- JAZEL Resume-2-1-2-1-3-1Dokumen2 halamanJAZEL Resume-2-1-2-1-3-1GirlieJoyGayoBelum ada peringkat

- Guide For Overseas Applicants IRELAND PDFDokumen29 halamanGuide For Overseas Applicants IRELAND PDFJasonLeeBelum ada peringkat

- Loading N Unloading of Tanker PDFDokumen36 halamanLoading N Unloading of Tanker PDFKirtishbose ChowdhuryBelum ada peringkat

- State Immunity Cases With Case DigestsDokumen37 halamanState Immunity Cases With Case DigestsStephanie Dawn Sibi Gok-ong100% (4)

- Ajp Project (1) MergedDokumen22 halamanAjp Project (1) MergedRohit GhoshtekarBelum ada peringkat

- Expense Tracking - How Do I Spend My MoneyDokumen2 halamanExpense Tracking - How Do I Spend My MoneyRenata SánchezBelum ada peringkat

- Selvan CVDokumen4 halamanSelvan CVsuman_civilBelum ada peringkat

- 2021S-EPM 1163 - Day-11-Unit-8 ProcMgmt-AODADokumen13 halaman2021S-EPM 1163 - Day-11-Unit-8 ProcMgmt-AODAehsan ershadBelum ada peringkat

- Check Fraud Running Rampant in 2023 Insights ArticleDokumen4 halamanCheck Fraud Running Rampant in 2023 Insights ArticleJames Brown bitchBelum ada peringkat

- CSEC Jan 2011 Paper 1Dokumen8 halamanCSEC Jan 2011 Paper 1R.D. KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Ces Presentation 08 23 23Dokumen13 halamanCes Presentation 08 23 23api-317062486Belum ada peringkat

- Allan ToddDokumen28 halamanAllan ToddBilly SorianoBelum ada peringkat

- D - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayDokumen13 halamanD - MMDA vs. Concerned Residents of Manila BayMia VinuyaBelum ada peringkat

- A320 Basic Edition Flight TutorialDokumen50 halamanA320 Basic Edition Flight TutorialOrlando CuestaBelum ada peringkat

- 6 V 6 PlexiDokumen8 halaman6 V 6 PlexiFlyinGaitBelum ada peringkat

- SND Kod Dt2Dokumen12 halamanSND Kod Dt2arturshenikBelum ada peringkat

- Government of West Bengal Finance (Audit) Department: NABANNA', HOWRAH-711102 No. Dated, The 13 May, 2020Dokumen2 halamanGovernment of West Bengal Finance (Audit) Department: NABANNA', HOWRAH-711102 No. Dated, The 13 May, 2020Satyaki Prasad MaitiBelum ada peringkat

- A Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Dokumen73 halamanA Novel Adoption of LSTM in Customer Touchpoint Prediction Problems Presentation 1Os MBelum ada peringkat

- Extent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home EconomicsDokumen47 halamanExtent of The Use of Instructional Materials in The Effective Teaching and Learning of Home Home Economicschukwu solomon75% (4)

- Tivoli Performance ViewerDokumen4 halamanTivoli Performance ViewernaveedshakurBelum ada peringkat

- EnerconDokumen7 halamanEnerconAlex MarquezBelum ada peringkat

- HSBC in A Nut ShellDokumen190 halamanHSBC in A Nut Shelllanpham19842003Belum ada peringkat

- Forecasting of Nonlinear Time Series Using Artificial Neural NetworkDokumen9 halamanForecasting of Nonlinear Time Series Using Artificial Neural NetworkranaBelum ada peringkat

- Oem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Dokumen43 halamanOem Functional Specifications For DVAS-2810 (810MB) 2.5-Inch Hard Disk Drive With SCSI Interface Rev. (1.0)Farhad FarajyanBelum ada peringkat

- HealthInsuranceCertificate-Group CPGDHAB303500662021Dokumen2 halamanHealthInsuranceCertificate-Group CPGDHAB303500662021Ruban JebaduraiBelum ada peringkat

- TSB 120Dokumen7 halamanTSB 120patelpiyushbBelum ada peringkat

- ESG NotesDokumen16 halamanESG Notesdhairya.h22Belum ada peringkat

- Research Article: Finite Element Simulation of Medium-Range Blast Loading Using LS-DYNADokumen10 halamanResearch Article: Finite Element Simulation of Medium-Range Blast Loading Using LS-DYNAAnonymous cgcKzFtXBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Eduardo M. Rivera: This Is A Riveranewsletter Which Is Sent As Part of Your Ongoing Education ServiceDokumen31 halamanDr. Eduardo M. Rivera: This Is A Riveranewsletter Which Is Sent As Part of Your Ongoing Education ServiceNick FurlanoBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Deming Principles That Help Healthcare Process ImprovementDokumen8 halaman5 Deming Principles That Help Healthcare Process Improvementdewi estariBelum ada peringkat