The Development of Pension Systems in Europe and The Role of Governance, Risk Management and External Consultants in The Change Process

Diunggah oleh

descooneyJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Development of Pension Systems in Europe and The Role of Governance, Risk Management and External Consultants in The Change Process

Diunggah oleh

descooneyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International School of Management

Ph.D. Program 1hesis

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk

management and external consultants in the change process

By

Des Cooney

Submitted in partial IulIilment oI the requirements oI the

Doctor of Philosophy

1uly 2010

Word count 86,179

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

2

'The more I know, the more I know how little I know...`

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

3

Executive summary

For the European pension industry, the last three years have witnessed seismic changes in

market conditions and therein levels oI retirement beneIits that individuals can expect Irom

their pension Iunds. Set against this background is an increasing awareness oI the problems that

an ageing population will present to society and in particular the need Ior the retired population

to have a suIIicient level oI retirement income in order to sustain both themselves and the

economy. This so called 'demographic time bomb' has occurred as a result oI three main

Iactors:

The departure oI the post-war baby-boom generation Irom the workIorce;

Continued increase in liIe expectancy;

Decreased Iertility rates since the 1970`s.

In addition to market turmoil and a greying population, the burden on state national pay-as-

you-go` (PAYG) pension systems is growing with large increases in expenditure on public

pensions projected Ior most European countries. The strain on overall public Iinances has put

the acquired rights oI state retirees at risk as it is now unclear whether or not social security

systems can aIIord to IulIil existing state pension obligations. As a result, individuals who

have paid into public pension systems now have to Iace up to the prospect oI receiving reduced

beneIits upon retirement. National pension systems have thus become a source oI

macroeconomic instability across Europe, threatening to constrain economic growth, and

proving to be an inequitable provider oI retirement income.

As a consequence oI the ageing population, the responsibility will Iall on the shoulders oI a

smaller group oI active workers to support a larger group oI retirees in the Iuture. While

governments are Iorced to reduce beneIits relative to contributions Ior national pension

schemes, the emphasis is moving to employers and individuals to take matters oI retirement

into their own hands. In order to address this issue, European governments have strived to put

in place mechanisms that encourage employers to establish pension schemes on behalI oI their

workers and individuals to put aside a greater proportion oI their personal savings into pension

or liIe assurance policies geared to retirement.

Across the euro zone, the size oI the private pension Iund industry diIIers extensively ranging

Irom 1.3 times GDP in the case oI the Netherlands to one tenth oI a percent Ior France

1

. Several

Iactors including the demographic structure oI the population, the Iiscal position oI

governments and socio-economic trends have contributed to signiIicant cross-country variation

in the structure oI pension Iunds and the level oI importance attached to them by individual

Member States. The gradual enlargement oI the EU as a single market and the advent oI a

single European currency has added a new dynamic to pension policy Iormulation and liIted the

reIorm issue Irom the domestic to the international arena. Global Iactors in the Iorm oI

international capital Ilows and the mobility oI labour have triggered an economic necessity Ior

EU Member States to coordinate pension systems and are shaping, and even driving the

pension reIorm agenda. Though certain Member States have undertaken signiIicant measures to

1

OECD (Ed.) (2005). Economic Survey oI the Euro Area 2005: Integrating Services Markets. Retrieved Irom

http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/8/31/35106741.pdI

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

4

reIorm their pension systems, there are still concerns that a number oI European countries lag

well behind.

The challenge Ior governments is to create an environment wherein the pension industry can

prosper, whilst at the same time make good on its commitments to scheme members. To

achieve this objective, legislation has Iorced retirement schemes to exert greater control on the

areas oI corporate governance, capital adequacy and risk management. The report examines

current European pension legislation and details standards and requirements that are expected

oI those operating in the arena.

In order to Irame the problem it is necessary to examine the most recent research conducted on

occupational pensions. Critique Irom leading pension specialist Iirms such as Mercer, Hewitt,

and Towers Watson is drawn upon in order to provide a comprehensive view oI the industry.

This is supported by research supplied by the Committee oI European Insurance and

Occupational Pensions Supervisors (CEIOPS), an oIIicial European regulatory body, and the

Organization Ior Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). A considerable amount oI

work has been conducted by both international organizations in order to help governments

address pension-related issues oI economic and social concern. Views were also drawn upon

Irom the European Federation Ior Retirement Provision (EFRP), which promotes the

development oI occupational pension, and acts as a pressure group Ior the interests oI the

national pension Iund associations in their dealings with Brussels. In addition, a series oI

reports published by the Investment and Pensions Europe (IPE) added to the reservoir oI

knowledge available Ior the analysis.

Adding to the debate

The paper traces the evolving role oI pensions in society and highlights current strategies

adopted by pension Iunds as they attempt to brave the current Iinancial crisis. Particular

attention is also paid to social protection Irameworks that have been put in place to limit the

risk oI Iunds under management. The objective oI the report is to make a contribution to the

pension debate currently taking place across Europe, through a detailed analysis oI the role oI

EU institutions in the pension reIorm process. Consideration is given to recent European

pensions` legislation as Brussels takes the initiative to boost occupational pension provision.

Given that each Member State is responsible Ior the design oI its national pension

inIrastructure, the paper highlights the diversity in design and composition oI the various Iorms

oI occupational pensions in the EU, and considers the Iuture outlook oI the pension industry in

an ever-changing environment.

The analysis attempts to add to the body oI thought that already exists on occupational

pensions. Through the application oI business theory and concepts, the paper seeks to test the

hypotheses that 'the pension Iund industry is short on governance and sound risk management

and therein will struggle to meet its liabilities to members.

The research was conducted at both secondary and primary levels. In the case oI the Iormer, a

thorough literature review was conducted discussing the various pension models that currently

exist in Europe and analysing the successes and shortcomings oI the systems to date.

Meanwhile, the primary research Iocused on Iive key issues which conIront the pension

industry:

Complexity oI legislation;

Governance;

Risk Management;

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

5

Fees;

Suitability oI products / vehicles.

The paper attempts to provide a comprehensive understanding oI all the diIIerent tasks

involved in administering a pension scheme. These include a detailed examination oI the theory

involved in the calculation oI risk Ior bonds and equities, and the processes surrounding asset

allocation in a pension Iund.

A summary oI the Iindings oI the primary research are placed at the end oI each relevant

chapter in the text. The research provided a constant supply oI issues Ior consideration that

directly impact the Iuture well-being oI Europeans. From this platIorm emerged a picture which

illustrated a lack oI harmony and transparency in pension systems and unveiled a number oI

discrepancies between walking the walk` and talking the talk`. The talk was oI transparency,

shared vision and sound risk management processes; the walk was oIten over zealous Iund

management leading ultimately to the underIunding oI pensions, and the oIIloading oI risk to

the individual.

The study demonstrated that there is a need Ior Ilexible occupational pension programs and

conIirms that they can successIully operate alongside and complement existing national

pension systems and therein encourage the movement oI labour across borders. The report

argues that the development oI suitable pension vehicles by the European Iinancial services

industry in tandem with evolving legislation is integral to the provision oI solutions Ior this

challenge. The aim oI the pan-European pension project is to create a suitable regulatory

structure in order to Iacilitate cross-border pension vehicles with a view to narrowing the

pension gap` and bringing economies oI scale to pension providers throughout the EU. From

there, the spur oI competition is likely to encourage the convergence oI national systems.

Growth in the private Iinancing oI pensions is indeed necessary to provide an adequate income

level Ior employees aIter retirement. A pan- European license enables employers to pool their

pension liabilities and assets whilst oIIering more cost-eIIicient solutions to the demographic

problems Iaced. To this end both pension and insurance-based Irameworks have been designed

to Iacilitate the complexities oI cross-border schemes.

The recent developments in the pension arena have led to many Iund administrators being

caught unawares. An industry that once enjoyed annual returns over a decade that outpaced

wage growth is now in crisis due to a shortage oI good governance and regulation. The

requirement Ior regulation is thus to be dynamic in an ever-changing environment. The

challenge is to be ahead oI the curve in legislative terms in order to prevent economies

overheating and stop runaway` stock-markets plunging over a cliII, therein damaging pension

Iund holdings.

The report concludes that it is diIIicult to choose the right moment to introduce eIIective

regulation; much political and economic commentary is made in the wake oI signiIicant events

that have taken place. The seeds oI regulatory change thus need to be sewn in advance oI

events occurring to prevent the economy being derailed. It is important thereIore to address the

elephant in the room` i.e. the level oI risk management and governance, or lack thereoI,

relating to pension Iunds.

The body oI the report is split into 7 sections:

Part I provides an overview oI the European pensions industry in terms oI its macro-

environmental setting. A PEST analysis is used to assess how political, economic, social and

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

6

technological issues impact pension systems. In order to examine current pension structures in

Europe, a multi-pillar pension Iramework is considered comprising oI publicly managed

pension schemes, occupational pensions and voluntary retirement savings. A series oI pension

models are analysed with particular attention being given to the DeIined BeneIit (DB), DeIined

Contribution (DC) and Hybrid structures that currently dominate the advanced economies oI

the Western World.

Part II oIIers a background to modern portIolio theory and the measurement oI risk. The

greatest challenge Ior all Iund managers is to try and gauge the level oI risk involved in

successIully meeting the pension schemes liabilities over time. It is important that the manager

Iully understands risk theory so that a sound platIorm can be built Ior decision-making. The

process oI quantiIying the total risk oI investing in a portIolio oI assets is analyzed with

particular emphasis given to risk diversiIication. The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

approach to making investment decisions is explored; this process addresses the relationship

between risk and return and calculates the cost oI capital` Ior a pension Iund in terms oI

holding capital to protect against non-hedgeable risk.

Part III conducts a review oI EU pension Irameworks and considers alternative models that are

currently being employed in the pensions and insurance sectors oI the industry. Rather than

have Member States develop a patchwork oI national pension regulations independent oI each

other, the EU has taken an integrated approach to reIorm with a view to tackling the budgetary

implications oI an ageing population and therein have more control over the Iuture dynamics oI

public expenditure.

This section examines closely the nature oI legislative reIorm that is taking shape in EU

member states. The most signiIicant step in recent years has been the creation oI a more

coordinated pension Iramework through the introduction oI a Pensions Directive in 2005

1

on

the activities and supervision of institutions for occupational retirement provision (the 'IORP

Directive), along with the Solvency II Directive (2007)

2

which was designed and developed

speciIically Ior insurance company structures.

This reIorm oI the legislation seeks to recognize the diIIerentiated pension systems in Member

States and oIIers a Iramework that makes it easier to conduct activities across borders in terms

oI Iiscal, social and economic hurdles. Applying a common set oI rules, the IORP Directive

oIIers a Iorm oI European passport Ior institutions establishing occupational pension schemes.

The Directive paves the way Ior an institution registered as an IORP in one Member State to be

recognized, and therein permitted to oIIer related occupational products and services, in other

EU member countries provided that it Iully respects the provision oI the social and labour law

in Iorce in the host Member State. The reIorm trajectory oI the IORP Directive thus represents

a convergence towards a single pension model.

1

IORP Directive, DIRECTIVE 2003//Stat. 1-12 (2003), http://eur-lex.europa.eu//LexUriServ.do?uriCELEX:32003L0041:EN:HTML.

2

Commission oI the European Communities. (2007, July 10). Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the taking-up and

pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance- Solvencv II. Retrieved Irom The European Commission website:

http://www.europeanlawmonitor.org///text.pdI

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

7

Alternatively, the Solvency II proposal Ior insurance companies seeks to bring about consistent

and harmonized supervision across the EU with the aim oI delivering better overall risk

management, improved mobility oI workers and a level playing Iield Ior all pension providers.

This section compares the two models with particular reIerence to governance and risk

management processes. The major distinction between these two pension models is the level oI

security extended to beneIiciaries. Occupational pension schemes do not seem to enjoy the

same level oI protection as insurance-based schemes, in terms oI saIeguards Ior solvency

capital. In addition, the Solvency II model would argue that competition in a single EU

market Ior pensions should be between providers and variations in scheme characteristics,

rather than between supervisory regimes.

The section concludes with a summary oI current opinions Irom existing European retirement

schemes on the question oI the complexities surrounding existing EU pension legislation.

Part IV addresses the key elements oI asset allocation and asset management strategy.

Investment returns are dependent on the type oI assets held in a portIolio and where and when

such assets are actually invested. Asset allocation involves the distribution oI assets among

diIIerent investment choices or classes. The investment allocation oI the Iund is oIten a

traditional mix oI asset classes which would include equities, bonds, cash, real estate, etc. The

main asset classes may thereaIter be divided Iurther into subclasses, such as small-cap stocks or

corporate bonds. The use oI alternative asset classes such as private equity, inIrastructure,

commodities and hedge Iunds are also explored.

Increased market volatility and a constantly changing environment are ongoing challenges Ior

pension Iund managers in their asset allocation strategy. As a result, the security selection

process and market timing become key aspects oI asset allocation strategy. To examine this process

in greater detail, three diIIerent asset management strategies are considered: active management,

passive management, and a core-satellite approach. Each approach is considered on its merits as a

route to achieving pension Iund investment objectives.

The impact oI currency Iluctuation and inIlation on pension schemes are also examined, with

particular attention being given to the risk that interest rates pose Ior honouring commitments.

Interest rate changes can trigger risks that may reduce the returns on cash deposits and Iixed

income securities. It is important thereIore Ior the manager to be aware oI the cause and eIIect

oI interest rate patterns and how the yield curve can aIIect projected Iunding plans.

Duration and immunization strategies are considered as models Ior pension providers to meet

their liabilities. The objective is Ior managers to invest policy holder premiums in Iixed income

securities that have the same present value to that oI the pension Iund liabilities. The analysis

thus demonstrates how duration and immunization strategies are Iit Ior purpose` in pension

Iund management.

A liability-driven approach to pension Iund management is a tactical Iorm oI asset allocation

applied as a portIolio insurance`, which essentially seeks to secure a minimum value Ior the

pension Iund at all times in order that liabilities can be met. The model builds on the risk

return approach oI portIolio management through the development oI strategies that reduce

pension Iunding volatility by aligning investments more closely with plan liabilities.

The existing research literature appeared to ignore to a large extent the complexities oI risk

management and the impact oI legislation on sponsors and trustees. Much oI the published

research is conducted by pension and management consultants that have a vested interest in

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

8

generating inIormation relating to the industry. Consequently, some oI the more pertinent

issues oI governance have tended to be skirted over rather than debated in a more objective

manner.

Part V oI the report highlights the key growth drivers in the pension sector and gives

consideration to emerging trends that may have an inIluence on the Iuture landscape. Fund

managers, the economy, retirees, workers, companies, the environment, and productivity are all

interconnected parts oI the same system. The inter-relationship between the roles oI the various

stakeholders is examined in the Iorm oI a pension Iood chain`.

It is the task oI governance to reconcile short term tactics with the long term strategy oI the

Iund. This section outlines the Iorces Ior change in the pension industry and puts an emphasis

on schemes accepting greater responsibility by ensuring better governance and moving more

toward Iiduciary management. With scheme sponsors increasingly seeking to outsource

portIolio and risk management activities, a premium has been put on the knowledge and

understanding oI pension systems. As the operating environment becomes more complex

sponsors are looking towards the Iiduciary model Ior external advice on plan design, risk -

management strategy and the use oI alternatives as an asset class.

Part VI conducts a detailed examination oI the characteristics oI a pensions` advisory group in

the consultancy arena. Pension Iunds continuously scour the market Ior new talent with a view

to enticing specialists into the industry. There is thereIore a unique opportunity Ior a

consultancy that can demonstrate a high level oI expertise supported by a sophisticated

knowledge management platIorm to Iill the current void.

In an attempt to explore the necessary attributes oI a pension consultancy service, a series oI

business concepts originally introduced by Michael Porter in his book Competitive Advantage.

Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (1985)

1

, are applied to an existing Paris-based

company named Axis Strategy Consultants. The models employed are in the Iorm oI the Value

Chain, the Five Forces model`, and a SWOT analysis, with a view to the development oI a

suitable competitive strategy Ior the pension consulting sector. The aim oI the consultancy

group is to add value to pension Iund clients by perIorming activities in a diIIerent or better

way than competitors. It is Ior the consultancy group to advise the pension scheme sponsor on

how best to develop uniqueness or advantage Ior the scheme with a view to delivering a greater

margin oI return Ior members.

Porter`s Value Chain` oIIers a systematic means oI displaying & categorizing events Ior the

pension Iund industry. It also highlights the positioning oI pension consulting / advisory groups

in the Iield oI pension Iund activities. The next step is Ior the consultancy to identiIy the key

Iactors aIIecting competition in an industry and diagnose their underlying causes by applying

the Five Forces model. ThereaIter a SWOT Analysis examines the key internal and external

Iactors in order to determine the limits oI what can be accomplished. Internal Iactors include

company strengths and weaknesses along with the personal values oI the key implementers,

whereas external Iactors Iocus on industry opportunities and threats and the broader societal

expectations. Only aIter having conducted a systematic analysis oI the environment and the

consultancy`s position within in it, can an eIIective competitive strategy be put in place.

1

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive Advantage. Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (First Edition ed.). New York: The Free Press.

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

9

The report highlights the diIIerent areas oI expertise possessed by the Axis Strategy

consultancy and concludes that the best way Iorward would be Ior the company to collaborate

with other advisory groups and seek to exploit synergies with partners that have

complementary skills.

Pension Iund management is a journey rather than a destination, it is thus oI great importance

that there are checks and balances along the way in order to ensure that objectives and targets

are being achieved. As part oI the competitive strategy oI Axis consultants it is necessary to

employ some Iorm oI benchmarking system in order to assess relative marketplace

perIormance compared with that oI main competitors. Indicators need to be selected Ior

perIormance measurement other than investment return. The report thus outlines a series oI

benchmarking measures that ought to be established in order to monitor key Iactors such as

quality oI advice, reliability, consistency oI service etc. in terms oI importance to customers.

These also include the use oI cost reduction benchmarks to measure the eIIiciency oI the

administration oI the Iund, along with metrics relating to transaction volumes and Iee

structures.

The report considers the design oI a balanced scorecard` as a tool to systematically measure

perIormance at Iinancial and operational levels and align activities across the business platIorm

to the interests and strategic goals oI the pension sponsor. With a continuous Ilow oI

inIormation and improved internal and external communications, the report argues that the

balanced scorecard would act as a nerve centre` Ior translating strategy into action.

Part VII concludes with a series oI recommendations that address the opportunities and

challenges presented by pension reIorm.

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

10

Table of Contents

Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 3

Adding to the debate ..................................................................................................................... 5

Introduction........................................................................................................................... 19

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 19

Questionnaire design................................................................................................................... 20

Sampling Irame ........................................................................................................................... 20

Data collection and analysis........................................................................................................ 20

Problems experienced ................................................................................................................. 21

Part I

Chapter 1 A macro analysis of the current European pension situation ...... 22

A} PE8T Ana|ys|s of European pens|on systems ......................................................................... 22

1. Political Analysis ................................................................................................................. 23

2. Economic analysis................................................................................................................ 24

3. Social Analysis..................................................................................................................... 24

4. Technological analysis......................................................................................................... 24

} |mpact of the outs|de env|ronment........................................................................................... 25

1. Political implications............................................................................................................ 25

a) Pressure on public pension provision ............................................................................... 25

b) Creation oI a common structure Ior pan-European pensions ........................................... 25

c) Mobility oI labour ............................................................................................................. 26

d) The development oI pension legislation ........................................................................... 27

2. Economic implications......................................................................................................... 27

a) Economic theory and pensions ......................................................................................... 27

b) The role oI private pension Iunds in Iinancial markets .................................................... 29

3. Social implications............................................................................................................... 29

a) The liIe cycle hypothesis.................................................................................................... 30

b) Building on diversity ......................................................................................................... 31

4. Technological implications .................................................................................................. 32

a) Stress testing and Iorecasting............................................................................................. 33

b) Asset allocation related issues ........................................................................................... 34

Chapter 2 Pension models .............................................................................................. 35

A} Pens|on mode|s and the ro|e of government superv|s|on......................................................... 35

1. Government and policy-driven model.................................................................................. 35

2. Employer-driven model ....................................................................................................... 35

3. Commercial-driven pension Iund model.............................................................................. 35

} 0ccupat|ona| pens|on schemes ............................................................................................... 36

1. The structure oI occupational pension Iunds ....................................................................... 36

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

11

2. Fund structure ...................................................................................................................... 36

3. Trustees ................................................................................................................................ 37

4. Pension Iund managers and consultant ................................................................................ 37

5. Pension Iund objectives........................................................................................................ 37

6} Funded pens|on f|nanc|ng veh|c|es.......................................................................................... 37

1. Role oI Iunded and non statutory pension schemes ............................................................ 38

2. Generic pension Iunds.......................................................................................................... 40

a) Non risk sharing plans ........................................................................................................ 40

b) Risk sharing plans............................................................................................................... 41

3. DeIined beneIit (DB) systems ............................................................................................. 42

a) DB pension systems in the UK........................................................................................... 42

b) DB pension systems in the Netherlands ............................................................................ 42

4. DeIined Contribution (DC) scheme structure ...................................................................... 42

0} The sh|ft from 0 pens|on schemes ....................................................................................... 43

The German pension reIorm oI 2001 and the strengthening oI DC orientation ..................... 43

E} Recent act|v|ty |n 0 and 06 systems .................................................................................... 45

1. DB vs DC Asset allocation at end oI 2009....................................................................... 45

2. DB/DC asset split at end oI 2009......................................................................................... 46

F} Factors |nf|uenc|ng the trend towards 06 schemes ................................................................. 47

1. Governance oI DC schemes ................................................................................................. 47

2. Structural problems associated with DC schemes ............................................................... 48

3. Design options...................................................................................................................... 49

4. DC schemes and risk management ...................................................................................... 50

5. Hybrid pension schemes ..................................................................................................... 51

Part II

Chapter 3 Portfolio theory and the measurement of risk ................................. 52

A} Portfo||o theory........................................................................................................................ 52

1. Expected return .................................................................................................................... 52

2. Measures oI risk................................................................................................................... 53

3. Calculation oI the variance................................................................................................... 54

} The Yodern portfo||o theory..................................................................................................... 55

1. Calculation oI the expected return` on a portIolio oI stocks............................................... 55

2. Covariance and correlation coeIIicient ................................................................................ 56

Chapter 4 Benefits of diversification......................................................................... 58

A} Asset corre|at|on...................................................................................................................... 58

1. Naive diversiIication............................................................................................................ 59

2. The eIIicient Irontier ........................................................................................................... 60

3. Risk diversiIication in pension Iunds................................................................................... 61

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

12

} how to assess the va|ue of d|vers|f|cat|on ............................................................................... 62

6} |mprovements |n d|vers|f|cat|on strateg|es for the future ......................................................... 63

Chapter 5 Measuring the market risk of a pension fund................................... 64

Capital asset pricing model (CAPM) ....................................................................................... 65

CAPM Example 1........................................................................................................ 67

CAPM Example 2........................................................................................................ 67

Part III

Review of EU pension frameworks

Chapter 6 The move to cross-border pension schemes ...................................... 68

Lewin`s force-field analysis for change................................................................................ 68

1. Driving Iorces Ior change in the pension industry............................................................... 69

2. Restraining Iorces Ior change in the pension industry......................................................... 69

Chapter 7 Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provisions (IORP)..... 72

A} The a|ms and structure of an |0RP........................................................................................... 72

1. Pooling oI assets and liabilities............................................................................................ 73

2. Quantitative beneIits ............................................................................................................ 73

3. Qualitative beneIits ............................................................................................................. 74

4. Structure oI a cross-border IORP......................................................................................... 74

} Sovernance - The 6omm|ttee of European |nsurance and 0ccupat|ona| Pens|ons 8uperv|sors

(6E|0P8} ...................................................................................................................................... 75

1. Regulatory abitrage .............................................................................................................. 75

2. Funding rules Ior IORP`s..................................................................................................... 75

3. Particulars oI the IORP ........................................................................................................ 77

4. EU - Social and labour law ................................................................................................. 77

5. DiIIerent types oI IORP....................................................................................................... 78

6} Techn|ca| prov|s|ons for |0RP's............................................................................................... 78

1. InIlation protection and salary indexation ........................................................................... 80

2. Interest rate used to discount the technical provisions ........................................................ 80

3. Mortality assumptions ......................................................................................................... 82

4. Expenses .............................................................................................................................. 82

5. Security mechanisms ........................................................................................................... 82

6. Ex ante security mechanisms regulatory own Iunds` and subordinated loans`.............. 83

7. Ex post security mechanisms - sponsor commitment` and guarantee Iunds` ................... 83

8. Reduction oI accrued pension rights and non-mandatory increases ................................... 84

0} The need for assessment ......................................................................................................... 85

1. Ranking ............................................................................................................................... 85

2. The development oI IORP`s in Europe ............................................................................... 86

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

13

Chapter 8 Occupational pensions and the Solvency II draft Directive ....... 87

A} The 8o|vency || 0|rect|ve.......................................................................................................... 87

1. Success Iactors in the insurance industry............................................................................. 87

2. Key Ieatures ......................................................................................................................... 88

3. Timeline ............................................................................................................................... 88

4. The regulatory Iramework 3 Pillars .................................................................................. 88

} Sovernance of |nsurance-based pens|on schemes.................................................................. 89

1. Supervisory review process (SRP)....................................................................................... 90

2. Report on solvency and Iinancial position .......................................................................... 91

6} R|sk management funct|on of |nsurance-based pens|on schemes .......................................... 91

1. A risk overview and governance Iramework ...................................................................... 92

2. Risk assessment by risk category ........................................................................................ 93

a) Non-liIe underwriting risk .................................................................................................. 93

b) LiIe and health underwriting risk ....................................................................................... 93

c) Market risk.......................................................................................................................... 93

d) Credit risk ........................................................................................................................... 93

e) Operational risk................................................................................................................... 94

I) Liquidity risk ....................................................................................................................... 94

g) Strategic risk ....................................................................................................................... 94

h) Reputational risk ................................................................................................................ 94

0} R|sk m|t|gat|ng act|v|t|es.......................................................................................................... 94

Capital adequacy management ............................................................................................ 94

Chapter 9 Solvency II and quantitative funding requirements....................... 96

0|8 3 framework .......................................................................................................................... 96

1. Technical provisions (TP) .................................................................................................... 96

2. Solvency II and regulatory capital requirements ................................................................ 98

a) Solvency capital requirement (SCR)................................................................................... 98

b) Internal models Ior solvency capital requirements ............................................................. 99

c) Minimum capital requirement Ior Solvency II Iramework................................................. 99

Example oI MCR calculation.................................................................................. 100

d) Stress tests.......................................................................................................................... 100

e) Own risk and solvency assessment (ORSA)...................................................................... 101

I) Actuarial Iunction............................................................................................................... 102

g) Annual solvency and Iinancial condition report ................................................................ 102

h) Valuation oI assets and liabilities ...................................................................................... 103

i) Group supervision............................................................................................................... 103

Chapter 10 The economic (solvency) balance sheet and the MCoC.............. 104

A} A market cons|stent approach to r|sk management ............................................................... 104

1. Market consistent value oI assets (MVA).......................................................................... 105

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

14

2. Market consistent value oI liabilities (MVL)..................................................................... 105

a) Expected present value oI Iuture cash Ilows and the use oI the SWAP rate .................... 105

b) The market value margin (MVM) Ior non-hedgeable risks.............................................. 106

3. The Solvency Capital Requirement (SCR) ....................................................................... 106

} Us|ng the market cost of cap|ta| (Y6o6} approach to estab||sh the YVY for non-hedgeab|e

r|sks........................................................................................................................................... 107

(i) Hedgeable risks ............................................................................................................... 107

(ii) Non-hedgeable risks ....................................................................................................... 108

1. The market value margin Ior non-hedgeable risk .............................................................. 108

2. Application oI the MCoC approach to MVM`s ................................................................ 109

3. Calculating the MCoC Ior pension Iunds .......................................................................... 109

4. The replicating portIolio ................................................................................................... 110

5. Role oI the SCR in times oI crisis ..................................................................................... 111

6} we|ghted average cost of cap|ta| (wA66} approach ............................................................. 111

An illustrative example .......................................................................................... 112

Chapter 11 Comparison of the IORP and Solvency II models ...................... 114

A} App|y|ng 0|8 3 to a 'f|na| pay' pens|on p|an .......................................................................... 114

Pension plans with risk sharing ............................................................................................ 115

} The quest for greater secur|ty for benef|c|ar|es...................................................................... 116

Summary of research findings on EU pension legislation................................................ 117

Part IV

Chapter 12 Asset allocation ....................................................................................... 118

A} Asset a||ocat|on approaches.................................................................................................. 118

1. Strategic asset allocation.................................................................................................... 118

2. Multi asset allocation ........................................................................................................ 119

} The |nf|uence of cu|ture on asset a||ocat|on........................................................................... 120

6} A current v|ew of pens|on fund asset a||ocat|on..................................................................... 121

1. European pension Iund asset evolution 1999 - 2009 ........................................................ 121

2. European pension Iund asset evolution 2007 - 2009 ........................................................ 121

3. The evolution oI European pension assets ......................................................................... 122

4. DiversiIication ................................................................................................................... 122

5. European pension Iunds under management vs GDP........................................................ 124

Chapter 13 Alternative investments ........................................................................ 125

A} hedg|ng |nstruments.............................................................................................................. 125

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

15

1. Use oI options .................................................................................................................... 125

2. Hedge Iunds ....................................................................................................................... 126

} Add|t|ona| asset c|asses ........................................................................................................ 127

1. Commodities ..................................................................................................................... 127

2. InIrastructure...................................................................................................................... 127

3. Private equity ..................................................................................................................... 127

4. Emerging markets .............................................................................................................. 129

6} The susta|nab|e deve|opment sector as an asset c|ass.......................................................... 130

The paradigm shiIt ................................................................................................................ 130

Summary of research findings on pension fund asset allocation..................................... 133

Chapter 14 Asset management strategy................................................................. 134

A} The quest for a|pha ................................................................................................................ 134

1. Passive management strategy ............................................................................................ 134

2. Active management strategy.............................................................................................. 134

} Yarket t|m|ng versus t|me...................................................................................................... 135

Core / satellite approach ........................................................................................................ 135

Summary of research findings on pension fund investment strategy ............................. 138

Chapter 15 Risk management and pension funds .............................................. 139

A} 6urrency and portab|e a|pha.................................................................................................. 139

1. Currency mandates Ior the institutional manager ............................................................. 140

2. Reduction in currency volatility ........................................................................................ 140

} The econom|cs of pens|on fund management........................................................................ 141

1. DeIlation v inIlation .......................................................................................................... 141

2. Interest rate risk.................................................................................................................. 142

3. EIIects oI inIlation and interest rates on pension Iunds ..................................................... 143

6} The use of bonds |n pens|on fund management..................................................................... 144

1. Factors aIIecting bond price sensitivity ............................................................................. 144

2. Development oI immunization strategies .......................................................................... 145

3. Duration ............................................................................................................................. 145

4. Bond duration calculation .................................................................................................. 146

5. Use oI bonds to meet liabilities.......................................................................................... 147

6. Pension Iunds and zero-coupon bonds............................................................................... 148

7. Yield curves ....................................................................................................................... 148

8. High yielding bonds ........................................................................................................... 149

0} The ro|e of 'swaps' |n pens|on fund management ................................................................. 149

1. Mitigation oI interest rate exposure ................................................................................... 149

2. Interest rate swaps .............................................................................................................. 150

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

16

3. Longevity swaps ................................................................................................................ 152

Summary of research findings on the consideration of de-risking strategies................. 154

Chapter 16 Review of the funding status of DB plans....................................... 156

A} Pens|on p|an fund|ng and the 't|me va|ue of money' .............................................................. 156

1. Rules governing Iunding levels.......................................................................................... 156

} The f|nanc|a| cr|s|s and the |mpact on fund|ng |eve|s............................................................. 158

1. UnderIunding issues in Ireland .......................................................................................... 159

2. UnderIunding issues in the UK.......................................................................................... 160

3. UnderIunding issues in the Netherlands ............................................................................ 160

4. UnderIunding issues in European multinationals .............................................................. 161

6} 6ompar|son of assets w|th ||ab|||t|es ..................................................................................... 162

Chapter 17 Asset liability management and liability driven investment 164

A} The move to ALY and L0| strateg|es...................................................................................... 164

1. Criticism oI the ALM approach ......................................................................................... 166

2. ALM and Iiduciary management ...................................................................................... 167

Chapter 18 A vehicle for the provision of sustainable income ....................... 168

Annuities ............................................................................................................................... 168

EIIect oI UK economic policy on annuity rates .................................................................... 169

Part V

Chapter 19 Maintaining standards in the pension sector................................ 170

1. Fiduciary management ....................................................................................................... 170

2. Need Ior good governance ................................................................................................. 171

3. Committing to responsible ownership ............................................................................... 172

Summary of research findings on safeguards used by pension fund trustees to minimize

risk............................................................................................................................................ 174

Chapter 20 Through the looking glass - Issues of concern for 2010............ 175

1. Solvency Issues .................................................................................................................. 175

2. Risk Management Strategy ................................................................................................ 175

3. BeneIits and stakeholders................................................................................................... 175

4. Agency issues..................................................................................................................... 175

5. Value proposition .............................................................................................................. 177

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

17

Summary of research findings on the perceived transparency of fees............................ 179

Summary of research findings on benchmarks used in the selection process of an

external fund manager............................................................................................................ 180

Chapter 21 Defining the pension industry of the future................................... 181

The pens|on fund journey ...................................................................................................... 181

1. Improvements in governance ............................................................................................. 181

2. Product proliIeration ......................................................................................................... 181

3. Pension design, towards a DC model................................................................................. 182

4. Organisational change new managers, new intermediaries, new competencies............. 182

5. Pressure Ior talent............................................................................................................... 183

6. New Iood chain .................................................................................................................. 183

} Srowth of a|ternat|ve strateg|es

1. New investment content ..................................................................................................... 183

2. The emergence oI sustainable development as an investment principle............................ 183

3. Stabilizing strategies .......................................................................................................... 183

4. Rebalancing oI pension Iunds ............................................................................................ 184

6} A v|ew on the future of pens|on schemes............................................................................... 187

No country Ior old men.......................................................................................................... 187

Summary of research findings on concerns for the future of the pension scheme ........ 188

Part VI

Chapter 22 The opportunity for consulting services ......................................... 189

A} Pens|on funds - Va|ue cha|n.................................................................................................. 189

6ompet|t|ve strategy: Ana|ys|s of the pens|on-consu|t|ng |ndustry and compet|tors ............. 192

1. Forces driving industry competition .................................................................................. 192

a) The bargaining power oI buyers ....................................................................................... 193

b) The bargaining power oI suppliers ................................................................................... 193

c) Intensity oI competition .................................................................................................... 194

d) Barriers to new entrants .................................................................................................... 194

e) Regulations on new entrants............................................................................................. 195

I) Threat oI substitute products ............................................................................................. 195

2. Industry attractiveness and success Iactors ........................................................................ 196

3. Importance of industry analysis ....................................................................................... 196

6ompet|t|ve strategy for Ax|s pens|on consu|t|ng serv|ces.................................................... 197

1. Internal Iactors ................................................................................................................... 197

2. External Iactors .................................................................................................................. 198

3. Strategic Iit ......................................................................................................................... 199

Performance and compet|t|ve advantage ............................................................................... 199

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

18

1. Service provider dependency............................................................................................. 201

2. A customer-centric approach to strategy............................................................................ 201

3. The inIormation well.......................................................................................................... 202

4. Sources oI competitive advantage...................................................................................... 202

5. The value model oI Axis Strategy Consultants.................................................................. 204

6. Five sources Iramework..................................................................................................... 204

E} enchmark|ng for pens|on adm|n|strat|on systems ............................................................... 205

1. Qualitative sources oI inIormation..................................................................................... 206

2. Sustainable competitive advantage ................................................................................... 206

3. Balanced scorecard ............................................................................................................ 207

a) The learning and growth perspective................................................................................ 208

b) The business process perspective ..................................................................................... 209

c) The customer perspective.................................................................................................. 209

d) The Iinancial perspective.................................................................................................. 209

Summary of research findings on preferences for the remuneration of outside

consultants ............................................................................................................................... 209

Chapter 23 Challenges for consulting services ................................................... 210

1. Strategy and implementation.............................................................................................. 210

2. Consultants` role in governance......................................................................................... 211

Summary of research findings on the added value of outside pension consultants....... 212

Part VII

Conclusions........................................................................................................................ 213

Recommendations - Route map to the future ...................................................... 215

Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 218

Glossary of Acronyms and Abbreviations.............................................................. 232

Appendix 1......................................................................................................................... 234

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

19

Introduction

How do vou swallow an elephant? One gulp at a time'

In order to solve a problem, it is necessary to break it down into manageable pieces. ThereaIter

the parts can be reassembled so as to look at the situation aIresh. The purpose oI this study is to

take a snapshot` oI the pension industry as it exists in Europe today and through a process oI

analysis, project where it will be in the Iuture. The research is not complete in its observations

and assertions, but moreover should be viewed as a work in progress`.

The role and development oI private pension provision is a key Iactor in addressing the

challenge Iaced by ageing European citizens. EU governments are becoming increasingly

aware oI the need to Ioster conditions that are conducive to saving. The analysis reveals that

there are many rules and exceptions in each Member State pension regulation. Pension systems

Iace common challenges; however each individual country has diIIerent issues that set it apart

Irom its neighbours in terms oI context (Hemerijck 2002)

1

.

In many western European countries, social insurance systems are provided primarily by the

state. Pension distributions increasingly account Ior a large part oI national insurance beneIits

in countries such as France, Germany, and Sweden. These type oI state beneIits are Iinanced by

the PAYG Iorm oI taxation, levied on both employers and employees. However, it is becoming

increasingly evident that the generous nature oI such programs acts as a disincentive Ior the

creation oI supplementary occupational schemes.

Pension Iunds play an important role in the economic and political structure oI EU states and

thus have a signiIicant impact on national government labour policies. It is necessary thereIore

that the various pension systems act in a co-ordinated manner Ior the beneIit oI all members oI

the EU. The objective oI reIorm is not to harmonise pension policies in Europe, but moreover

to create an eIIicient market. Bolkestein (2000)

2

advocated that the structure oI pensions was a

political decision Ior Member States and emphasized that the reIorm process should be

primarily concerned with increasing the eIIiciency and security oI Iunded schemes. ReIorms

are oIten a socially sensitive subject Ior Member States as each country wishes to retain its

beneIit adequacy levels within the reIorm process.

The paper analyses the evolution oI the pension Iund market set against the background oI a

trans-national political economy in Europe. A wide range oI Iorces are at play in terms oI socio

economic and political activities with many constituencies showing signs oI conIlict as opposed

to convergence along common threads.

Methodology

The research component oI this project seeks to monitor the progress oI pension schemes in

European countries in the wake oI the current Iinancial crisis. The report tests the hypotheses

that:

'the European pension Iund industry is short on governance and sound risk management and

therein will struggle to meet its liabilities to members.

1

Hemerijck, A. (2002, April). The self-transformation of the European social model(s). Retrieved Irom http://library.Ies.de/pdI-Iiles//-4/.pdI

2 Bolkestein, F. (2000, March 30). Pensions funds in the European Union. Speech presented at Financial Times` European Pensions

ConIerence , Brussels.

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

20

To this end the pension industry is analyzed in depth with grounded theory applied to the

various strands oI pension Iund management in order to highlight any shortIall in the existing

processes. Set against this background opportunities are explored Ior a new type oI consulting

group that would seek to engage with all stakeholders using a `balanced scorecard` approach to

the provision oI advice.

Questionnaire design

In an attempt to gather Iresh inIormation on developments in the pension sector, it was decided

to approach trustees and Iund managers Ior their opinions in the Iorm oI a survey. The

questionnaire expands upon existing work in the Iield published by Lucida plc (2009)

1

, Towers

Perrin (2008)

2

and BiIinance (2009)

3

. It seeks to add to the body oI thought by addressing a

number oI occupational pension areas that oIten slip under the radar oI multi-national

employers in Europe. Ten key issues were outlined in the questionnaire and delivered in a

multiple-choice Iormat (see Appendix 1); these questions were designed to test the above

hypotheses.

Sampling frame

It was important to select a sample oI the population that was truly representative oI the

pension Iund sector. A directory oI registered European pension Iunds was used as the

sampling Irame with existing pension schemes targeted in the UK, Holland and Ireland. These

three particular European Member States were chosen as their pension systems have proven

over the years to be in a more advanced position than their European counterparts in terms oI

structure and design.

A key objective was Ior the sample to deliver accurate inIormation that was a true reIlection oI

the current state oI the industry. To this end managers in executive positions were targeted Ior

their opinions on pension issues. Respondents were Iound to be very Iorthcoming with

inIormation, despite the already signiIicant demands on their time.

Data collection and analysis

A group-mail soItware program designed by InIacta Ltd (2010)

4

was used to deliver the

questionnaire by email to the targeted industry personnel. This soItware product oIIered a

1

Lucida PLC. (2009, October). The Pension Pulse Survev 2009. Retrieved Irom Lucida PLC website: http://www.lucidaplc.com/centre/pulse-

report-2009

2

Towers Perrin. (2008, December). The changing nature of corporate pensions in the UK. Retrieved Irom Towers Perrin website:

http://www.towersperrin.com//?countrygbr&webcGBR///Iinal.pdI

3

BiIinance. (2009, March). Pension Survev 2009. Retrieved Irom BiIinance website: F:\Integration oI European Pensions\Survey -

biFinance.mht

4

InIacta Ltd. (n.d.). GroupMail (Version 5) |Computer soItware|. Retrieved Irom http://www.group-mail.com///.asp

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

21

template that could be customized Ior use in an online survey and also Iacilitated the analysis oI

the data collected in graphical Iormat.

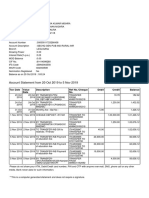

The survey was conducted in March 2010. The questions were sent to a representative sample

oI 200 European-based corporate pension plans. 50 oI those who responded were based in the

UK, 28 Irom the Netherlands, and 22 Irom Ireland. OI these schemes, 75 were DB type

structures, 18 Hybrid pension plans, and 7 Money Purchase or DC schemes. In terms oI

capital value, schemes with more than t5bn assets under management accounted Ior 18 oI

respondents, whereas pension plans with between t1 5bn represented 41 oI the group. Plans

with less than t1bn oI assets under management also accounted Ior 41 oI respondent oI the

survey.

Questions were targeted to a cross-section oI personnel involved in the management oI pension

Iunds. The largest category oI respondent was that oI Pension PortIolio Fund Manager / ChieI

Pension OIIicer at 44. Fund Administrators were the second largest group oI respondents

with 17; Trustees, Fund Secretary`s and Fund Managers each represented 11 oI

respondents, with Human Resource Directors accounting Ior 6 oI those answering the survey.

Problems experienced

A pilot study was conducted in the Iirst instance with a select number oI respondents, in order

to identiIy any obstacles that would hinder answering the survey questions. The initial Ieedback

highlighted the Iollowing design Iailings:

The subject` oI the email did not prompt a suIIicient number oI recipients to click

through to the survey itselI;

With 34 questions in the original survey, it took an average oI 5 minutes to complete;

As there were 4 pages oI questions to complete in the survey, a number oI respondents

lost interest halI way through;

Many respondents avoided the open questions` oI the survey.

The questionnaire was thus reconstructed to take into account the time constraints oI

respondents. It was decided that a much shorter questionnaire would be more successIul in

soliciting responses. A new subject` line: The Pension Siren - International pension survey,

was used to spark the interest oI the target audience. In addition, as an incentive to complete the

questionnaire, an oIIer to share the survey Iindings was made to would-be respondents.

ThereaIter a request was sent to each respondent asking Ior their permission to contact them

again with a view to gathering additional inIormation. Through the development oI an

interactive relationship with respondents, the aim is to have a Iinger on the pulse` oI the

industry so that an ongoing stream oI analysis can be conducted which helps promote initiatives

that assist in the alignment oI interests Ior all pension Iund stakeholders.

The development of pension systems in Europe and the role of governance, risk management and external consultants

in the change process

22

Part I

Chapter 1 A macro analysis of the current European pension situation

Looking backwards through the telescope

The issue surrounding an ageing population and its impact on society is perhaps the greatest

challenge oI modern times; one that may make the current Iinancial crisis pale into

insigniIicance in comparison. In order to understand Iully the scale oI the problem, it is

necessary to examine in detail all the Iorces that are at play in the wider environment. There are

a myriad oI macro-environmental issues which inIluence the European pensions landscape.

These include government policy, demographic change, tax legislation, and various trade

restrictions between member states.

A} PE8T Ana|ys|s of European pens|on systems

To help Irame these external Iactors Ior the purpose oI analysis, a PEST model (see Diagram

1.1) is applied that categorizes issues under the Iollowing headings:

Political Iactors;

Economic Iactors;

Social Iactors;