Acute Pancreatitis

Diunggah oleh

Mariquita BuenafeHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Acute Pancreatitis

Diunggah oleh

Mariquita BuenafeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Systems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City COLLEGE OF NURSING

A Case Report About

Acute Pancreatitis

Submitted to: Mary Ann de Dios, RN, MSN

Submitted by: Ma. Cresencia S. Buenafe

NUR70A

I.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatitis is a disease in which the pancreas becomes inflamed. Pancreatic damage occurs

when the digestive enzymes are activated before they are secreted into the duodenum and begin attacking the pancreas. Acute pancreatitis is a sudden inflammation that occurs over a short period of time. In the majority of cases, acute pancreatitis is caused by gallstones or heavy alcohol use. Other causes include medications, infections, trauma, metabolic disorders, and surgery. In up to 30% of people with acute pancreatitis, the cause is unknown. The severity of acute pancreatitis may range from mild abdominal discomfort to a severe, lifethreatening illness. However, the majority of people with acute pancreatitis recover completely after receiving the appropriate treatment. In very severe cases, acute pancreatitis can result in bleeding into the gland, serious tissue damage, infection, and cyst formation. Severe pancreatitis can also create conditions which can harm other vital organs such as the heart, lungs, and kidneys.

A. Latest Statistics or incidence of the Disorder

Acute pancreatitis has an incidence of approximately 40 cases per year per 100,000 adults. In 2007, nearly 220,000 patients with acute pancreatitis are expected to be admitted to non federally funded hospitals. In 1998, 183,000 patients with acute pancreatitis were admitted. This trend in rising incidence has been recognized over the past several decades Worldwide, the incidence of acute pancreatitis ranges between 5 and 80 per 100,000 populations, with the highest incidence recorded in the United States and Finland. In Luneburg, Germany, the incidence is 17.5 cases per 100,000 people. In Finland, the incidence is 73.4 cases per 100,000 people. Similar incidence rates have been reported in Australia. The incidence of disease outside North America, Europe, and Australia is less well known.

[8]

In Europe and other developed nations, such as Hong Kong, more patients tend to have gallstone pancreatitis, whereas in the United States, alcoholic pancreatitis is most common.

B. Current Trends/Journal Current trends in the management of infected necrotizing pancreatitis

Sakorafas GH, Lappas C, Mastoraki A, Delis SG, Safioleas M.

Severe acute pancreatitis is a potentially life-threatening disease. Pancreatic necrosis is associated with an aggravated prognosis, while superimposed infection is almost always lethal without surgery. Bacterial translocation mainly from the gut is the most widely accepted mechanism in the pathogenesis of infected pancreatic necrosis. Infected pancreatic necrosis should be suspected in the presence of the usual markers of systemic inflammation (i.e., fever and leukocytosis), organ failure, or a protracted severe clinical course. The diagnostic method of choice to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatic necrosis is contrast-enhanced computed tomography, where necrotic areas are evidenced as regions without enhancement. The presence of pancreatic necrotic infection should be based on a combination of clinical manifestations, results of laboratory investigation (mainly increased levels of CRP and / or procalcitonin), and can be confirmed by image-guided fine-needle aspiration and gram stain /culture of the aspirates. Surgery remains the treatment of choice for the management of infected pancreatic necrosis and involves open necrosectomy (debridement) and wide drainage of the peripancreatic areas, often in association with continuous irrigation. Planned reoperations may be required to achieve complete removal of the necrotic / infected material. The timing of surgery is of paramount importance; ideally, surgery should be performed after 2 or 3 weeks from the onset of pancreatitis. Recently, various minimally invasive approaches have been described, but they have not been compared in prospective trials with the classical open surgery. Antibiotic therapy is routinely used in patients with infected necrotizing pancreatitis, in conjunction with surgical debridement; its role, however, in the management of patients with sterile necrosis is recently questioned. Nutritional support should be taken into consideration in these patients; enteral nutrition should be preferred over total parenteral nutrition to improve the anatomical and functional integrity of the gut mucosa, thereby preventing bacterial translocation.

II.

ASSESSMENT

History Recent operative or other invasive procedures Family history of hypertriglyceridemia Previous biliary colic and binge alcohol consumption (major causes of acute pancreatitis)

Physical Assessment

Fever (76%) and tachycardia (65%); hypotension Abdominal tenderness, muscular guarding (68%), and distention (65%); diminished or absent bowel sounds

Jaundice (28%) Dyspnea (10%); tachypnea; basilar rales, especially in the left lung In severe cases, hemodynamic instability (10%) and hematemesis or melena (5%); pale, diaphoretic, and listless appearance

Occasionally, extremity muscular spasm secondary to hypocalcemia

Risk Factors Age The risk of developing pancreatic cancer increases with age, with over 8 in 10 cases of pancreatic cancer occurring in people aged over 60 years. It is rare in people under 40.

Ethnicity

In the UK Asian people have a lower incidence of pancreatic cancer.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking is the only established risk factor for pancreatic cancer. Smoking increases the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. This includes smoking cigarettes, cigars, pipes and chewing tobacco. A study published in 2011 estimated that 29% (nearly 1 in 3) of pancreatic cancer cases in the UK are caused by smoking.

The risk of pancreatic cancer rises in line with the amount of cigarettes a person smokes per day. A British study found that people who smoked up to 25 cigarettes a day had almost double the risk of dying from pancreatic cancer than people who had never smoked. People smoking more than 25 cigarettes a day had nearly three times the risk.

However a large scale European study found that the level of risk amongst former smokers returned to that of non-smokers after five years of stopping smoking.

Research looking at smoking among people at risk of familial pancreatic cancer found that smokers developed pancreatic cancer 10 years earlier than nonsmokers. The study also found that smoking is a significant risk factor for people identified as being at familial risk or having a number of first degree relatives (parent, child or sibling) affected by the disease. It advised that those with a number of people affected by pancreatic cancer within their family should not smoke.

Some research suggests there may be an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in people who are regularly exposed to environmental tobacco smoke, especially in childhood.

It is not clear why smoking increases pancreatic cancer risk. It might be because cigarette smoke contains chemicals called nitrosamines which are carcinogenic.

Pipe and cigar smokers The risk of developing pancreatic cancer is increased by 50% in cigar and pipe

smokers.

Body mass index and weight

A review of the evidence on weight and BMI (Body Mass index) suggests that a higher BMI and increased abdominal fatness increase the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. The review found that there was a 10% increase in risk for a five point increase in BMI.

A UK study published in 2011 suggested that 12% (around 1000) of cases of pancreatic cancer were related to being overweight or obesity. (Overweight was classed as a BMI of over 25 and obesity as a BMI of over 30).

The World Cancer Research Fund estimates that maintaining a healthy weight could help prevent 15% of pancreatic cancer cases in the UK a year.

Physical activity Reviews of the available evidence suggest that occupational physical activity

may have a protective effect and lower the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. However, no relationship has been found between recreational physical activity and pancreatic cancer.

Alcohol

Chronic heavy alcohol use is a risk factor for chronic pancreatitis which is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer. However, research evidence on a direct link between alcohol and risk of pancreatic cancer is mixed. There does not appear to be an increased risk of developing pancreatic cancer from moderate alcohol consumption.

However, some studies suggest that heavy drinking (more than 3 drinks a day) may lead to an increased risk of developing the disease.

Diet A review of the available research evidence suggests that eating processed meat

(e.g. sausage, ham, bacon) increases the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Eating around one serving (50g) per day increased the risk by 19%.

There is mixed evidence about the role of saturated fats and risk of pancreatic cancer. Some studies have found a link between eating large amounts of saturated fat and developing pancreatic cancer but others have not found a link.

Research studies have not found a link between eating fruit and vegetables and risk of developing pancreatic cancer.

Evidence suggests that it is unlikely that the consumption of coffee has any impact on risk of pancreatic cancer.

NSAIDs (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) (including Aspirin)

NSAIDs have been shown to have a beneficial effect in reducing the risk of some cancers, but the available research evidence does not show any association between NSAIDS and risk of pancreatic cancer.

Causes

In the majority of cases, acute pancreatitis is caused by gallstones and alcohol use. Other causes include medications, lipid (triglyceride) disorders, infections, surgery, or trauma to the abdomen. In up to 30% of people with pancreatitis, the cause is unknown.

III.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The Endocrine System

The endocrine system (see Figure 1 on the next page) is one of the bodys main systems for communicating, controlling and coordinating the bodys work. It works with the nervous system, reproductive system, kidneys, gut, liver, pancreas and fat to help

maintain and control the following: body energy levels, reproduction, growth and development, internal balance of body systems, called homeostasis, and responses to surroundings, stress and injury. The endocrine system accomplishes these tasks via a network of glands and organs that produce, store, and secrete certain types of hormones. Hormones are special chemicals that move into body fluid after they are made by one cell or a group of cells. Different types of hormones cause different effects on other cells or tissues of the body. Endocrine glands make hormones that are used inside the body. Other glands make substances like saliva that reach the outside of the body. Endocrine glands and endocrine-related organs are like factories. They produce and store hormones and release them as needed. When the body needs these substances, the bloodstream carries the proper types of hormones to specific targets. These targets may be organs, tissues, or cells. To function normally, the body needs glands that work correctly, a blood supply that works well to move hormones through the body to their target points, receptor places on the target cells for the hormones to do their work, and a system for controlling how hormones and produced and used.

Figure 1. The Anatomy of the Human Endocrine System

Pancreas The pancreas was discovered by Herophilus (335-280 B.C.E.), a Greek anatomist and surgeon. A few hundred years later, Ruphos, another Greek anatomist, gave the pancreas its name. The term "pancreas" is derived from the Greek pan, meaning "all," and kreas, meaning "flesh" (Harper 2007).

The pancreas (See Figure 3 below) is a 6-10 inch elongated organ weighing 65 to 160 grams and lying in the abdominal cavity. It lies posterior to the stomach, anterior to the kidneys, and empties into the duodenum portion of the small intestine. It can be divided into five regions: (1) the head, which touches the duodenum, (2) the body, which lies at the level of second lumbar vertebrae of the spine, (3) the tail, which extends towards the spleen, (4) the uncinate process, and (5) the pancreatic notch, which is formed at the bend of the head and body. The pancreatic duct or duct of Wirsung runs the length of the pancreas and empties into the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater. The common bile duct usually joins the pancreatic duct at or near this point. Many people also have a small accessory duct, the duct of Santorini, which extends from the main duct more upstream (towards the tail) to the duodenum, joining it more proximally than the ampulla of Vater.

Figure 2. The Anatomy of the Human Pancreas

IV.

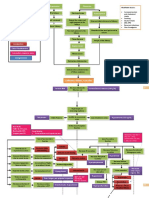

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Acute pancreatitis may occur when factors involved in maintaining cellular

homeostasis are out of balance. The initiating event may be anything that injures the acinar cell and impairs the secretion of zymogen granules; examples include alcohol use, gallstones, and certain drugs. At present, it is unclear exactly what pathophysiologic event triggers the onset of acute pancreatitis. It is believed, however, that both extracellular factors (eg, neural and vascular response) and intracellular factors (eg, intracellular digestive enzyme activation, increased calcium signaling, and heat shock protein activation) play a role. In addition, acute pancreatitis can develop when ductal cell injury leads to delayed or absent enzymatic secretion, as with the CFTR gene mutation. Once a cellular injury pattern has been initiated, cellular membrane trafficking becomes chaotic, with the following deleterious effects:

Lysosomal and zymogen granule compartments fuse, enabling activation of trypsinogen to trypsin

Intracellular trypsin triggers the entire zymogen activation cascade Secretory vesicles are extruded across the basolateral membrane into the interstitium, where molecular fragments act as chemoattractants for inflammatory cells

Activated neutrophils then exacerbate the problem by releasing superoxide (the respiratory burst) or proteolytic enzymes (cathepsins B, D, and G; collagenase; and

elastase). Finally, macrophages release cytokines that further mediate local (and, in severe cases, systemic) inflammatory responses. The early mediators defined to date are tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8. These mediators of inflammation cause an increased pancreatic vascular permeability, leading to hemorrhage, edema, and eventually pancreatic necrosis. As the mediators are excreted into the circulation, systemic complications can arise, such as bacteremia due to gut flora translocation, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), pleural effusions, gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage, and renal failure. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) can also develop, leading to the development of systemic shock. Eventually, the mediators of inflammation can become so overwhelming to the body that hemodynamic instability and death ensue. In acute pancreatitis, parenchymal edema and peripancreatic fat necrosis occur first; this is known as acute edematous pancreatitis. When necrosis involves the parenchyma, accompanied by hemorrhage and dysfunction of the gland, the inflammation evolves into hemorrhagic or necrotizing pancreatitis. Pseudocysts and pancreatic abscesses can result from necrotizing pancreatitis because enzymes can be walled off by granulation tissue (pseudocyst formation) or via bacterial seeding of pancreatic or peripancreatic tissue (pancreatic abscess formation). Li et al compared 2 set of patients with severe acute pancreatitis one with acute renal failure and the other without itand determined that a history of renal disease, hypoxemia, and abdominal compartment syndrome are significant risk factors for acute renal failure in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. In addition, patients with acute

renal failure were found to have a significantly greater average length of stay in the hospital and in the intensive care unit (ICU), as well as higher rates of pancreatic infection and mortality. Symptoms

Upper abdominal pain that radiates into the back; patients may describe this as a "boring sensation" that may be aggravated by eating, especially foods high in fat.

Swollen and tender abdomen Nausea and vomiting Fever Increased heart rate

V.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT A. Diagnostic and Laboratory Procedures Once a working diagnosis of acute pancreatitis is reached, laboratory tests are

obtained to support the clinical impression, such as the following:

Serum amylase and lipase Liver-associated enzymes Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatine, and electrolytes Blood glucose Serum cholesterol and triglyceride Complete blood count (CBC) and hematocrit; NLR C-reactive protein (CRP) Arterial blood gas values

Serum lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) and bicarbonate Immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) Diagnostic imaging is unnecessary in most cases but may be obtained when the

diagnosis is in doubt, when pancreatitis is severe, or when a given study might provide specific information required. Modalities employed include the following:

Abdominal radiography (limited role): Kidneys-ureters-bladder (KUB) radiography with the patient upright is primarily performed to detect free air in the abdomen

Abdominal ultrasonography (most useful initial test in determining the etiology and the technique of choice for detecting gallstones)

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (used mainly for detection of microlithiasis and periampullary lesions not easily revealed by other methods)

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning (generally not indicated for patients with mild pancreatitis but always indicated for those with severe acute pancreatitis)

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP; to be used with extreme caution in this disease and never as a first-line diagnostic tool)

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP; not as sensitive as ERCP but safer and noninvasive)

Other diagnostic modalities include the following:

CT-guided or EUS-guided aspiration and drainage Genetic testing

Acute pancreatitis is broadly classified as either mild or severe. According to the Atlanta classification, severe acute pancreatitis is signaled by the following:

Evidence of organ failure (eg, systolic blood pressure below 90 mm Hg, arterial partial pressure of oxygen [Pa O2] 60 mm Hg or lower, serum creatinine level 2 mg/dL or lower, GI bleeding amounting to 500 mL or more in 24 hours)

Local complications (eg, necrosis, abscess, pseudocyst) Ranson score of 3 or higher or APACHE score of 8 or higher

B. Drugs Antibiotic therapy is employed as follows: Antibiotics (usually of the imipenem class) should be used in any case of pancreatitis complicated by infected pancreatic necrosis but should not be given routinely for fever, especially early Antibiotic prophylaxis in severe pancreatitis is controversial; routine use of antibiotics as prophylaxis against infection in severe acute pancreatitis is not currently recommended

C. Surgical Management

Surgical intervention (open or minimally invasive) is indicated when an anatomic complication amenable to a mechanical solution is present. Procedures appropriate for specific conditions involving pancreatitis include the following:

Gallstone pancreatitis: Cholecystectomy

Pancreatic duct disruption: Image-guided percutaneous placement of a drainage tube into the fluid collection ; stent or tube placement via ERCP; in refractory cases, distal pancreatectomy or a Whipple procedure

Pseudocysts: None necessary in most cases; for large or symptomatic pseudocysts, percutaneous aspiration, endoscopic transpapillary or transmural techniques, or surgical management

Infected pancreatic necrosis: Image-guided aspiration; necrosectomy Pancreatic abscess: Percutaneous catheter drainage and antibiotics; if no response, surgical debridement and drainage

D. Treatment

Medical management of mild acute pancreatitis is relatively straightforward. The patient is kept NPO (nil per osthat is, nothing by mouth), and intravenous (IV) fluid hydration is provided. Analgesics are administered for pain relief. Antibiotics are generally not indicated. If ultrasonograms show evidence of gallstones and if the cause of pancreatitis is believed to be biliary, a cholecystectomy should be performed during the same hospital admission. Feeding should be introduced enterally as the patients anorexia and pain resolves. Patients can be initiated on a low-fat diet initially and need not invariably start their dietary advancement using a clear liquid diet. Serum amylase and lipase levels can be elevated in patients with brain injury (eg, cerebrovascular accident or brain trauma). These patients are generally cared for in

an intensive care unit (ICU) and require mechanical ventilation. Pancreatic enzyme elevations may rise and fall dangerously over many days to weeks. The elevation is believed to result from hyper stimulation of the pancreas via a central mechanism, but no evidence of acute pancreatitis is present on imaging studies. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis require intensive care. Within hours to days, a number of complications (e.g., shock, pulmonary failure, renal failure, gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding, or multi-organ system failure) may develop. The goals of medical management are to provide aggressive supportive care, to decrease inflammation, to limit infection or super infection, and to identify and treat complications as appropriate. Autoimmune pancreatitis is a rare condition. Corticosteroids should not be used to treat this condition in the short term in patients who are suspected of having autoimmune pancreatitis and who present with acute pancreatitis. No evidence-based guidelines specify when a patient should be transferred to a more experienced or skilled medical center. However, if severe acute pancreatitis is suggested either by the Atlanta criteria or by a C-reactive protein (CRP) level above 10 mg/dL, Ranson score of 4 or higher, or Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score of 9 or higher, consider transfer to an institution where an intensivist staffs the critical care unit and an interested subspecialist experienced in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatitis is available.

Further inpatient care depends on whether any of the complications of severe pancreatitis develop and how well patients respond to treatment. This ranges from a few days to several months of intensive care. Patients can be discharged when their pain is well controlled with oral analgesia, they are able to tolerate an oral diet that maintains their caloric needs, and all complications have been addressed adequately. Prevention

When the cause of pancreatitis can be determined, prevention depends on preventing the etiologic agent from causing subsequent episodes. In patients with documented gallstone pancreatitisand probably in those with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis as wellcholecystectomy is required. In patients who abuse alcohol, a dedicated person (eg, physician, psychologist, addiction counselor) who can help the patient overcome the addiction to alcohol is required. When an uncommon cause of pancreatitis is identified, the path of prevention is specific to the etiology.

VII.

REFERENCES

Internet Sources: http://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/digestive-diseases-pancreatitis http://www.pancreaticcancer.org.uk/information-and-support/facts-aboutpancreatic-cancer/risk-factors

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/181364-overview#aw2aab6b2b3aa

Journal http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20180753

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Liver AbscessDokumen3 halamanLiver AbscessLyiuiu TranBelum ada peringkat

- Leptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsDokumen6 halamanLeptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsJackii DoronilaBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Management Pancreatic CancerDokumen2 halamanNursing Management Pancreatic CancerKit NameKo100% (2)

- Prostate CancerDokumen6 halamanProstate CancerfheisanzBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology (Risk Factors & Symptoms)Dokumen20 halamanPathophysiology (Risk Factors & Symptoms)Ann Michelle TarrobagoBelum ada peringkat

- Gallbladder Removal Procedure and RecoveryDokumen6 halamanGallbladder Removal Procedure and RecoveryTom Bayubs-tucsBelum ada peringkat

- What Is HyperglycemiaDokumen7 halamanWhat Is HyperglycemiaFelisa Lacsamana GregorioBelum ada peringkat

- Ulcerative ColitisDokumen7 halamanUlcerative ColitisShaira Anne Fuentes BaroniaBelum ada peringkat

- Dec 21 23 Case Study ModuleDokumen7 halamanDec 21 23 Case Study ModuleKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isBelum ada peringkat

- Cholelithiasis 0232Dokumen118 halamanCholelithiasis 0232Kz LonerBelum ada peringkat

- Tarlac State University College of Nursing case study on choledocholithiasisDokumen53 halamanTarlac State University College of Nursing case study on choledocholithiasisCzarina ManinangBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology of Acute CholecystitisDokumen2 halamanPathophysiology of Acute CholecystitisKush KhannaBelum ada peringkat

- Hemorrhagic Cerebro Vascular DiseaseDokumen37 halamanHemorrhagic Cerebro Vascular Diseasejbvaldez100% (1)

- Predisposing Conditions, Management and Prevention of Chronic Kidney DiseaseDokumen52 halamanPredisposing Conditions, Management and Prevention of Chronic Kidney DiseaseSaad MotawéaBelum ada peringkat

- UROLITHIASISDokumen84 halamanUROLITHIASISJheanAlphonsineT.MeansBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Paper Liver CirrhosisDokumen65 halamanClinical Paper Liver CirrhosisNeølie Abello LatúrnasBelum ada peringkat

- Mastectomy: Prepared By: Hilario, Eunice Lamoste, Jenebelle Lopez, Maria SofiaDokumen34 halamanMastectomy: Prepared By: Hilario, Eunice Lamoste, Jenebelle Lopez, Maria SofiaSofia LopezBelum ada peringkat

- CholecystitisDokumen27 halamanCholecystitisKadek Ariarta MahartamaBelum ada peringkat

- Small Bowel ObstructionDokumen2 halamanSmall Bowel ObstructionSrividya PushpalaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study Cervical Cancer InterviewDokumen4 halamanCase Study Cervical Cancer InterviewLYNDON MENDIOLABelum ada peringkat

- Liver Cirrhosis CaseDokumen8 halamanLiver Cirrhosis Casemarlx5Belum ada peringkat

- Predisposing and precipitating factors of abdominal aortic aneurysmDokumen6 halamanPredisposing and precipitating factors of abdominal aortic aneurysmSandrine BarredoBelum ada peringkat

- Assessment 2 - Nursing Case Study - 2019Dokumen2 halamanAssessment 2 - Nursing Case Study - 2019Chinney ArceBelum ada peringkat

- Structured Health Teaching On Proper Nutrition of Common ConditionDokumen11 halamanStructured Health Teaching On Proper Nutrition of Common ConditionFry FryBelum ada peringkat

- InTech-Diabetic Foot and GangreneDokumen25 halamanInTech-Diabetic Foot and GangrenePutu Reza Sandhya PratamaBelum ada peringkat

- Bladder Cancer Types, Symptoms, Tests & TreatmentDokumen1 halamanBladder Cancer Types, Symptoms, Tests & TreatmentCarmina AguilarBelum ada peringkat

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy SurgeryDokumen2 halamanLaparoscopic Appendectomy SurgeryNycoBelum ada peringkat

- Case Presentation on Abdominal Compartment SyndromeDokumen29 halamanCase Presentation on Abdominal Compartment Syndromesgod34100% (1)

- Acute PancreatitisDokumen10 halamanAcute PancreatitisAndrés Menéndez RojasBelum ada peringkat

- Intestinal ObstructionDokumen48 halamanIntestinal ObstructionMahmoud AbuAwadBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyDokumen46 halamanCase Study Presented by Group 22 BSN 206: In-Depth View On CholecystectomyAjiMary M. DomingoBelum ada peringkat

- GIT Checklist With RationaleDokumen5 halamanGIT Checklist With RationaleTeal OtterBelum ada peringkat

- Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDokumen9 halamanBenign Prostatic Hyperplasiaanju rachel joseBelum ada peringkat

- Intestinal ObstructionDokumen27 halamanIntestinal ObstructionAna AvilaBelum ada peringkat

- Congestive Heart Failure Guide: Causes, Symptoms, DiagnosisDokumen20 halamanCongestive Heart Failure Guide: Causes, Symptoms, DiagnosisAshok KumarBelum ada peringkat

- Competency Appraisal Midterm ExaminationsDokumen9 halamanCompetency Appraisal Midterm ExaminationsRellie Castro100% (1)

- Hyperglycemic Crisis in Acute Care: Purwoko Sugeng HDokumen49 halamanHyperglycemic Crisis in Acute Care: Purwoko Sugeng HBee DanielBelum ada peringkat

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTI)Dokumen32 halamanUrinary Tract Infections (UTI)Ruqaya HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Abdominal Trauma Signs, Symptoms and Nursing CareDokumen24 halamanAbdominal Trauma Signs, Symptoms and Nursing CareSurgeryClassesBelum ada peringkat

- Upper GI Bleed - SymposiumDokumen38 halamanUpper GI Bleed - SymposiumSopna ZenithBelum ada peringkat

- Bladder TumorDokumen32 halamanBladder TumorAngelynChristabellaBelum ada peringkat

- Chest InjuryDokumen4 halamanChest InjuryFRANCINE EVE ESTRELLANBelum ada peringkat

- PancreatitisDokumen23 halamanPancreatitissalmanhabeebekBelum ada peringkat

- MSU Buug College Nursing Assessment for Abdominal PainDokumen30 halamanMSU Buug College Nursing Assessment for Abdominal Painllanelli.graciaBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Appendicitis Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationDokumen5 halamanPediatric Appendicitis Clinical Presentation - History, Physical ExaminationBayu Surya DanaBelum ada peringkat

- A Case Presentation On AppendecitisDokumen30 halamanA Case Presentation On AppendecitisrodericpalanasBelum ada peringkat

- Liver Abscess Causes and SymptomsDokumen6 halamanLiver Abscess Causes and SymptomsKenneth SunicoBelum ada peringkat

- Hypertension: Colegio de San Juan de LetranDokumen13 halamanHypertension: Colegio de San Juan de LetranJenna AbuanBelum ada peringkat

- Hypertension Obstruction: Chronic Renal FailureDokumen3 halamanHypertension Obstruction: Chronic Renal FailureDiane-Richie PezLo100% (1)

- Diabetes PathophysiologyDokumen6 halamanDiabetes PathophysiologyKatelyn CherryBelum ada peringkat

- Pleural EffusionDokumen12 halamanPleural EffusionWan HafizBelum ada peringkat

- Case StudyDokumen34 halamanCase StudyBSNNursing101Belum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology of ArrhythmiasDokumen15 halamanPathophysiology of ArrhythmiasJonathan MontecilloBelum ada peringkat

- Pancretic Cancer Case Study - BurkeDokumen52 halamanPancretic Cancer Case Study - Burkeapi-282999254Belum ada peringkat

- Case Stydy Angina PectorisDokumen46 halamanCase Stydy Angina PectorissharenBelum ada peringkat

- Anal Canal: Fissure in Ano HaemorrhoidsDokumen37 halamanAnal Canal: Fissure in Ano Haemorrhoidsyash shrivastavaBelum ada peringkat

- Stomach Cancer Print EditedDokumen6 halamanStomach Cancer Print EditedSyazmin KhairuddinBelum ada peringkat

- Hypovolemic ShockDokumen2 halamanHypovolemic ShocklarklowBelum ada peringkat

- Community Acquired Pneumonia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsDari EverandCommunity Acquired Pneumonia, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsBelum ada peringkat

- Signs and Symptoms: Colorectal Cancer, Also Called Colon Cancer or Large Bowel Cancer, IncludesDokumen18 halamanSigns and Symptoms: Colorectal Cancer, Also Called Colon Cancer or Large Bowel Cancer, Includesphvega06Belum ada peringkat

- Nutrition Imbalance Care PlanDokumen7 halamanNutrition Imbalance Care PlanMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Pedia Drugs ImagesDokumen1 halamanPedia Drugs ImagesMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Journal in PediatricsDokumen7 halamanJournal in PediatricsMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- RitodrineDokumen4 halamanRitodrineMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- CHN - Drug StudyDokumen1 halamanCHN - Drug StudyMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Effects of Aging in The Cardiovascular SystemDokumen6 halamanEffects of Aging in The Cardiovascular SystemMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- UrinalysisDokumen5 halamanUrinalysisMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Hemolytic Disease of The Fetus and Newborn JournalDokumen10 halamanHemolytic Disease of The Fetus and Newborn JournalMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Focus ChartingDokumen3 halamanFocus ChartingMan GatuankoBelum ada peringkat

- Pathophysiology of Erythroblastosis Fetalis - RH IsoimmunizationDokumen1 halamanPathophysiology of Erythroblastosis Fetalis - RH IsoimmunizationRalph Delos SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Risk for Infection Nursing Care PlanDokumen3 halamanRisk for Infection Nursing Care PlanMariquita Buenafe57% (7)

- NCP CvaDokumen4 halamanNCP CvaMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Journal in Anemia and BTDokumen19 halamanJournal in Anemia and BTMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- DR DrugsDokumen2 halamanDR DrugsMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Systems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City College Of Nursing Drug Study Student Nurse: Buenafe, Ma. Cresencia S. Yr. /Level: BSN III Date: September 25, 2012Dokumen4 halamanSystems Plus College Foundation Balibago, Angeles City College Of Nursing Drug Study Student Nurse: Buenafe, Ma. Cresencia S. Yr. /Level: BSN III Date: September 25, 2012Mariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- DengueDokumen5 halamanDengueMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- DR DrugsDokumen2 halamanDR DrugsMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- CardiomegalyDokumen91 halamanCardiomegalyMariquita Buenafe100% (1)

- Coronary Artery DiseaseDokumen38 halamanCoronary Artery DiseaseMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Cardio Drug StudyDokumen8 halamanCardio Drug StudyMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Cardio Drug StudyDokumen8 halamanCardio Drug StudyMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- PromDokumen14 halamanPromMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Nursing FinalDokumen35 halamanPediatric Nursing FinalMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- Cardio Drug StudyDokumen8 halamanCardio Drug StudyMariquita BuenafeBelum ada peringkat

- NCP Cholecystectomy RevisedDokumen7 halamanNCP Cholecystectomy RevisedMariquita Buenafe100% (4)

- Coronary Artery DiseaseDokumen9 halamanCoronary Artery DiseaseMariquita Buenafe100% (1)

- Explanation of BenefitsDokumen1 halamanExplanation of Benefitsmohamed hamedBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Diabetes Prevention ProgramDokumen19 halamanPhilippine Diabetes Prevention Programkoala100% (1)

- UG Curriculum Vol II PDFDokumen247 halamanUG Curriculum Vol II PDFRavi Meher67% (3)

- Current JobsDokumen24 halamanCurrent JobsFatima SajidBelum ada peringkat

- Igas Flow ChartDokumen1 halamanIgas Flow ChartYi Wei KoBelum ada peringkat

- What Do Language Disorders Reveal About Brain-Language Relationships? From Classic Models To Network ApproachesDokumen14 halamanWhat Do Language Disorders Reveal About Brain-Language Relationships? From Classic Models To Network ApproachesvalentinepoulainBelum ada peringkat

- APA - DSM 5 Depression Bereavement Exclusion PDFDokumen2 halamanAPA - DSM 5 Depression Bereavement Exclusion PDFDaniel NgBelum ada peringkat

- 'NEXtCARE UAE - ASOAP FormDokumen1 halaman'NEXtCARE UAE - ASOAP FormMohyee Eldin RagebBelum ada peringkat

- Socolov Et. Al., 2018 Cognitive Impairment in MEDokumen19 halamanSocolov Et. Al., 2018 Cognitive Impairment in MERicardo Jose De LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Muscles of MasticationDokumen8 halamanMuscles of MasticationNaisi Naseem100% (1)

- IVMS ICM-Heart MurmursDokumen22 halamanIVMS ICM-Heart MurmursMarc Imhotep Cray, M.D.Belum ada peringkat

- Best Practice Statement AuditDokumen2 halamanBest Practice Statement Auditns officeBelum ada peringkat

- Sigmoid Volvulus: Vertical Incision) (Suspected To Be Acute and Not ChronicDokumen3 halamanSigmoid Volvulus: Vertical Incision) (Suspected To Be Acute and Not ChronicTan Hing LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Supraspinatus TendinitisDokumen23 halamanSupraspinatus TendinitisTafzz Sailo0% (1)

- Head NursingDokumen22 halamanHead NursingGian Arlo Hilario CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Rash DDDokumen5 halamanRash DDSyed Moin HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Murder Mystery LabDokumen19 halamanMurder Mystery Labapi-451038689Belum ada peringkat

- Challenges in Hospital IT & Networking Design - Niranjan - Invest2Care PDFDokumen15 halamanChallenges in Hospital IT & Networking Design - Niranjan - Invest2Care PDFVelram ShanmugamBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Robert WolkDokumen7 halamanDr. Robert WolktmcazBelum ada peringkat

- Healthcare Delivery Systems: Improving Interdependence of The Healthcare TeamDokumen15 halamanHealthcare Delivery Systems: Improving Interdependence of The Healthcare Teamapi-580145439Belum ada peringkat

- BibliographyDokumen14 halamanBibliographyllalla08Belum ada peringkat

- World Health Report 2008Dokumen148 halamanWorld Health Report 2008dancutrer2100% (2)

- Salwa Maghrabi Teacher Assistant Nursing Department: Prepared byDokumen30 halamanSalwa Maghrabi Teacher Assistant Nursing Department: Prepared byPearl DiBerardino100% (1)

- Treatment Plan AssignmentDokumen2 halamanTreatment Plan AssignmentyourzxtrulyBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report: JR: Melissa Leviste and Nami MuzoDokumen28 halamanCase Report: JR: Melissa Leviste and Nami MuzoNami MuzoBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1.A: First Aid for Common Outdoor EmergenciesDokumen30 halamanLesson 1.A: First Aid for Common Outdoor EmergenciesAnonymous LToOBqDBelum ada peringkat

- A Placebo-Controlled Test of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Comorbid Insomnia in Older AdultsDokumen11 halamanA Placebo-Controlled Test of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy For Comorbid Insomnia in Older Adultssilvia dwi puspitaBelum ada peringkat

- Sophie Griswold Recc Letter Mary OconnellDokumen1 halamanSophie Griswold Recc Letter Mary Oconnellapi-356127291Belum ada peringkat

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokumen24 halamanNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptireneaureliaBelum ada peringkat

- Patient care and discharge planDokumen2 halamanPatient care and discharge planBryan Carmona100% (1)