The Turnover Intentions of Information Systems Auditors

Diunggah oleh

dearsaputriDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Turnover Intentions of Information Systems Auditors

Diunggah oleh

dearsaputriHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Accounting Information Systems

The turnover intentions of information systems auditors

Agung D. Muliawan 1, Peter F. Green 2, David A. Robb

UQ Business School, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 4072

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

The turnover rate of Information Systems auditors is an emerging problem for the profession. In his study of factors affecting resource allocations to Information Systems Audit departments, Lucy [Lucy, R.F. Factors affecting information systems audit resource allocation decisions. Thesis, The University of Texas, Arlington, 1998.] found that the average Information Systems (IS) auditor has four years of IS Audit experience. Dunmore [Dunmore D.B. Farewell to the information systems audit profession. Internal Auditor 1989; February:4248.] argues that this high turnover of IS auditors will limit systems audit knowledge. Unlike prior research investigating turnover intentions of IS auditors, this study specically includes factors that reect the higher level needs of IS audit professionals. The need to satisfy personal and professional growth exerts a particularly strong inuence on IS auditors' turnover intentions. Further, our study conrms that IS auditors' share similar characteristics to other IS professionals rather than with general accountants and auditors. Organizations wanting to retain their IS auditors should provide regular opportunities for their IS auditors to satisfy their personal growth needs. Crown Copyright 2009 Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Article history: Received 21 December 2008 Received in revised form 13 February 2009 Accepted 9 March 2009 Keywords: IS auditors Turnover intentions Growth needs Satisfaction

1. Introduction The turnover rate of Information Systems auditors is an emerging problem for the profession. In his study of factors affecting resource allocations to Information Systems Audit departments, Lucy (1998) found that the average Information Systems (IS) auditor has four years of IS Audit experience. He found also

Corresponding author. Tel.: +61 7 3381 1219; fax: +61 7 3381 1227. E-mail addresses: p.green@business.uq.edu.au (P.F. Green), a.robb@business.uq.edu.au (D.A. Robb). 1 Tel.: +61 7 3365 6976; fax: +61 7 3365 7285. 2 Tel.: +61 7 3381 1029; fax: +61 7 3381 1227. 1467-0895/$ see front matter. Crown Copyright 2009 Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.accinf.2009.03.001

118

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

that when Information Systems auditors move to a new position, 47% leave their current organizations. The percentage is even greater for Information Systems auditors at the supervisory and management level, with 55% and 64% respectively, moving to other organizations to advance their careers. As early as 1989, Dunmore argued that high levels of turnover of IS auditors would limit systems audit knowledge. Dunmore believed IS auditors with limited professional experience would lack high-level systems knowledge and prociency. Furthermore, such turnover causes organizations to incur higher turnover costs. Roth and Roth (1995) report that training and recruiting costs for a single employee in public accounting rms reached between US$4000 and US$8000. Alarmingly, these items often account for only 20% of total turnover costs, the remaining 80% comes from hidden costs, e.g., inefciencies and waning productivity (Dunn, 1995). This current study's primary objective is to enhance understanding and knowledge of the factors that inuence the turnover intentions of Information Systems auditors. The overarching research question for this study is: what factors signicantly inuence the turnover intention of IS auditors? Second, what factors signicantly inuence IS auditor job satisfaction and organizational commitment? Our investigation is motivated by three principal factors. First, although ample research has been done on turnover, few studies have addressed the issue of IS auditor turnover. Given the importance placed on IS audit and the problems associated with managing relatively high IS auditor turnover, such lack of research is unexpected (Lucy, 1999). Second, while a prior study of IS auditor turnover (Quarles, 1994b) found some factors associated with general auditors and accountants explained IS auditor turnover intentions, studies of other professional groups (e.g., Benke and Rhode, 1980; Harrel and Stahl, 1984; and Watson, 1975) indicate different factors may be implicated. Quarles's (1994b) study reported R2 of 0.53 for turnover intention, 0.54 for job satisfaction, and 0.55 for organizational commitment. Unlike the historical focus of general auditors work, IS audit is future-oriented and more difcult to quantify (Dunmore, 1989). Such differences likely affect the antecedent factors and their levels relating to IS auditor turnover intentions. For example, the need to be up to date with new technical developments being used in business processes differentiates some of these factors from those affecting turnover intentions of traditional accountants. Third, IS audit has taken on a new importance since Quarles' (1994b) IS auditor turnover study. IS auditors' working environment has become more complicated and technologies are more advanced. For example, the scope and focus of IS audit, the relationship with nancial audit, skill requirements for auditors, and technologies differ markedly from the time of Quarles's study (Bagranoff and Vendrzyk, 2000). More recently, and particularly in light of legislation such as the SarbanesOxley Act, IS audit has become a key component of good governance. Contemporary nancial reporting processes are driven by information systems. Such systems are deeply integrated in initiating, authorizing, recording, processing and reporting nancial transactions (ITGI, 2006). No research, however, appears to have investigated the problem of IS auditor turnover in the post-SOX landscape. Consequently, the turnover intention model of Quarles's study likely requires revision. In the following section of this paper motivation theories are presented to provide background for this study. Next, based on prior relevant studies and theoretical considerations we develop our model and hypotheses, followed by a description of the research method this study employed. Lastly, we discuss the results of the data analyses and draw conclusions and implications from this study. 2. Background In this section we present three different, but related motivation theories. These theories help guide our selection of salient factors likely affecting personnel turnover. 2.1. Motivation theories Needs-based theories of motivation such as those proposed by Maslow (1943), Herzberg (1959), and Alderfer (1969) have long been mainstays of management theory. Their focus on the individual's quest to satisfy his/her levels of needs, particularly with regard to ones' working lives, have helped us to better understand employees' needs and motivations. Indeed, Maslow's (1943) and Alderfer's (1969) needs hierarchies are based on the assertion that humans are motivated by unsatised needs, and that certain

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

119

lower level needs have to be largely satised before higher level needs can be fullled (Hitt et al., 2005). O'Connor and Yballe's (2007) reassessment of Maslow's work, in particular, conrmed that satisfaction of lower level needs, such as safety, social, and esteem needs, leaves employees to pursue higher level needs such as self-actualization. Herzberg's (1959) motivational theory contends that there are two types of motivation factors: hygiene factors and motivation factors. Hygiene factors de-motivate if not present, for example, physical working conditions, salary, or interpersonal relations. Conversely, motivation factors can motivate when present, for example, achievement, advancement, and responsibility. Like Maslow's and Alderfer's higher level needs, Herzberg's motivation factors centre largely on the need for personal development. As O'Connor and Yballe (2007) point out, however, the need for personal development is not, in itself, an endpoint, but an ongoing process. If those personal development needs are not being satised by a person's current employment circumstances, then Maslow's, Alderfer's, and Herzberg's theories predict that people will be strongly motivated to satisfy those unfullled needs. Indeed, such motivation will likely be sufcient to precipitate pursuit of alternative employment. Within the overarching scope of these general motivation theories we intend to investigate the factors that lead IS auditors to change their jobs. As professionals, IS auditors are highly educated and trained in the technical aspects of auditing and IS, hence their professional needs will likely centre on those higher level personal development and growth needs advocated by motivation theorists. As Business Week (2008) notes, one of the Big Four auditing rm's key strategies to recruit and retain staff relies heavily on personal development and learning. Accordingly, one might reasonably expect that IS auditors would seek organizational settings that provide a clear role fostering both their personal and professional growth. The study of turnover has received much attention since the 1900s, with estimates of publication of qualitative and quantitative investigations of turnover exceeding 1500 (Muchinsky and Morrow, 1980). Given the breadth of prior research, some researchers (e.g., Locke, 1976; Mobley, 1982) argue that personnel turnover is largely explained by job satisfaction and organizational commitment. While Quarles (1994a) argues that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are products of complex interactions among multiple factors, he suggests there are other, antecedent controllable factors, that should rst be identied when seeking to explain the motivations for IS auditor turnover. Gallegos (1991) hypothesizes that several work-related factors may explain IS auditors' high turnover rate. First, IS auditors' unique position allows intimate knowledge of organizational operations. For this reason, many organizations use the IS audit position as a training ground for their future managers. Second, when IS auditors become highly procient they may feel their job lacks challenge, particularly if engaged in repetitive tasks. Such lack of challenge may lead to boredom and increase their desire for career progression. Third, the IS auditing profession lacks upward mobility with few directors and senior IS auditors. Dunmore (1989) and Tongren (1994) suggest that limited career prospects contribute to IS auditors' pursuit of higher levels of responsibility and remuneration in other organizations. Again, these factors all emphasize the importance of fullling personal growth needs for IS auditors. Quarles (1994a) applied a model used to investigate turnover intentions of general auditors and accountants, surveying members of the EDP Auditors Association (now Information Systems Audit and Control AssociationISACA) employed in public accounting, industry, and government. He reported that both organizational commitment and job satisfaction have inverse effects on turnover intentions. Together organizational commitment and job satisfaction explained 53% of the variance in those intentions. Job satisfaction had a positive and direct relationship with organizational commitment. Role ambiguity, role conict, and external job opportunities had a negative and direct relationship with organizational commitment. Together these latter three variables explained 55% of the variance in the organizational commitment. Quarles (1994a) further reports that role ambiguity had an inverse effect on job satisfaction, and that both participation in decision making and supervisory status positively affected respondents' job satisfaction. These three variables together explained 54% of the variance in job satisfaction for Quarles. In contrast to the predictions of motivation theorists, (e.g., Maslow, Alderfer, and Herzberg) Quarles's ndings do not expressly address the matter of individuals seeking to satisfy their higher level needs. Given the professional status of IS auditors, and prior research (e.g., Dunmore, 1989; Gallegos, 1991; Tongren, 1994), satisfying higher level needs appears to be a priority of IS auditors. Accordingly, to investigate the

120

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

extent to which the issue of personal growth needs affect IS auditors' turnover intention, our turnover intention model specically includes and measures that variable. 3. Model and hypotheses development This section introduces our IS auditor turnover intention model and the dependent variable. We next turn to the independent variables and develop our hypotheses relative to the factors likely to affect IS auditors' turnover intentions. Consistent with Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), to understand intentions, we must rst specify the factors that lead to intent. In turn, therefore, we deal with organizational commitment, job satisfaction, the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment, role conict and ambiguity, promotion opportunities, pay satisfaction, and personal growth. Furthermore, Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) reinforce the direct relationship between behavioral intention and action. 3.1. Turnover intention model Fig. 1 shows this study's research model. Our research model has its basis in the Quarles (1994a) and ERG models and is informed by a review of prior studies on turnover of IS auditors, and the theories of motivation. The research model comprises seven independent variables: role conict, role ambiguity, promotion opportunities, pay satisfaction, growth needs, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. Couger et al.'s (1992) study found that satisfying higher level needs was important to hi-tech professionals. Accordingly, because our model includes the higher-level needs factor, personal growth, it offers greater insights into IS auditors' turnover intentions than Quarles's (1994b) model. 3.2. The dependent variable The dependent variable is the IS auditors' turnover intentions. Consistent with Ajzen and Fishbein's (1980) assertion that behavioral intention is the most immediate determinant of actual behavior, we use the dependent variable, turnover intention, as a proxy for actual turnover. Other studies (see e.g., Mobley et al., 1979; Steel and Ovalle, 1984; Miller et al., 1979; Arnold and Feldman, 1982; Cotton and Tuttle, 1986; Rasch and Harrell, 1990) also report consistent positive relationships exist between turnover intention and actual turnover behavior. Moreover, Bluedorn's (1982)

Fig. 1. Turnover intention of information systems auditors.

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

121

research of 23 prior studies found that individuals' turnover intentions matched their actual turnover behavior. 3.3. The independent variables The independent variables were chosen for two reasons. First, the variables are work-related, i.e., they describe the interface between individual workers and organizations (Muchinsky and Morrow, 1980). Second, while Quarles (1994b) notes that management does not have direct control of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, there are antecedent factors, however, the management of an organization can directly control that signicantly and positively affect job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Quarles, 1994b). 3.4. Organizational commitment Organizational commitment refers to the degree an individual is involved in, and identies with, a particular organization (Steers, 1977). Porter et al. (1974) identify three facets of organizational commitment: (1) strong belief in, and acceptance of, organizational goals and values; (2) willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization; and (3) a denite desire to maintain organizational membership. An individual who is committed to an organization will, therefore, be less likely to express a desire to leave an organization. A number of studies have conrmed that organizational commitment has a signicant inverse impact on turnover (actual or intended) for employees in different types of organization (Abelsen, 1987; Michaels and Spector, 1982; Williams and Hazer, 1986). Several studies focussing on general accountants (Arnold and Feldman, 1982), accountants in both public accounting and industrial organizations (Aranya and Ferris, 1984), and governmental accountants (Meixner and Bline, 1989) have reported similar results. Like generalist accountants, Quarles (1994b) notes IS auditors' turnover intentions are also affected by organizational commitment. Based on the prior argument H1. Organizational commitment has a direct, negative effect on turnover intention. 3.5. Job satisfaction Locke (1976) contends that job satisfaction represents a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from one's job or job experiences. Job satisfaction reects the degree to which the work environment meets or reinforces the needs of the individual (Weiss et al., 1967). Supervision, co-workers, and career satisfaction are some of the many facets of job satisfaction (Ironson et al., 1989). Scarpello and Campbell (1983) argue that additive measures of job satisfaction, however, may be no better at communicating actual job satisfaction than overall ratings of job satisfaction. Consequently, in this study we regard job satisfaction as an overall measure, rather than the aggregate of individual facets of job satisfaction. Industrial psychology research validates an inverse relationship between job satisfaction and turnover (Sorensen, 1990). For accountants and auditors, several studies indicate similar results (e.g., Arnold and Feldman, 1982; Gregson, 1990; Harrel and Stahl, 1984; Rasch and Harrell, 1990). Harrell et al. (1986) report a signicant direct inverse relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intent for internal auditors. Further, Couger et al. (1979) report that personnel in IS related professions place particular stock in job satisfaction. For that reason, job satisfaction is likely a key component of the turnover intentions of IS auditors. Based on the prior argument we present the following hypothesis for IS auditors: H2a. Job satisfaction has a direct, negative effect on turnover intention. 3.6. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment Porter et al. (1974) argue that satisfaction is less stable, but formed more quickly, than organizational commitment. Porter et al. considered commitment as a global link between an individual and an

122

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

organization, with satisfaction being a component of commitment. Stevens et al. (1978) described that, through an exchange process, individuals assess the benets and costs of staying with an organization. When the benets outweigh the costs commitment results, suggesting that job satisfaction may be a predictor of commitment. Moreover, after analyzing studies on organizational commitment and job satisfaction, Locke and Latham (1990, p.250), concluded that it seems logical that satisfaction would affect organizational commitment, although satisfaction is certainly not its only determinant. Gregson (1992) examined the causal ordering and importance of organizational commitment and job satisfaction on the relationship between various independent variables and turnover among accounting professionals. Based on the results of his analysis of two data sets using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), he concluded that both job satisfaction and organizational commitment should be included in models that predict turnover. Gregson (1992) concluded that while numerous prior studies have debated causal ordering between job satisfaction and organizational commitment, those studies have agreed that a signicant, positive relationship exists between the variables. Quarles (1994a) study of internal auditors, similarly, noted a positive relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. We propose the following relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: H2b. Job satisfaction has a direct, positive effect on organizational commitment. 3.7. Role conict and role ambiguity A role is a set of expectations about the behavior of a person holding a particular position within an organization (Lee, 1996). Role conict occurs when there is incompatibility between the expected set of behaviors perceived by the focal person and those perceived by role senders. Role ambiguity occurs when the set of behaviors expected for a role is unclear (Katz and Kahn, 1978). Mowday et al. (1982) argue that the psychological processes explaining the correlation between role conict, role ambiguity, and organizational commitment are not yet well understood. While the correlation between the aforementioned factors may not be precisely understood, Jackson and Schuler's (1985) meta analysis of 96 studies on role conict and role ambiguity concluded that organizational commitment is negatively correlated with both role ambiguity and role conict. Moreover, prior studies indicate that role conict and role ambiguity are associated with lower organizational commitment (see e.g., Baird, 1969; Organ and Green, 1981; Podsakoff et al., 1986). Couger et al. (1979) observe IS professionals' generally low satisfaction with supervisors. Given the inuence supervisors can wield over factors like role conict and role ambiguity, such low satisfaction may be reected in reduced organizational commitment. We propose the following relationships between role conict, role ambiguity and organizational commitment. H3a. Role conict has a direct, negative effect on organizational commitment. H3b. Role ambiguity has a direct, negative effect on organizational commitment. Role theory (Kahn et al., 1964) suggests that role ambiguity will increase the probability that a person will be dissatised with their role. Schaubroeck et al. (1989) argues that role ambiguity hinders performance improvements, and hence limits individuals' ability to obtain rewards, potentially reducing job satisfaction. In a study of senior auditors of a (then) big-eight accounting rm, Senatra (1980) found that role ambiguity was negatively related to job satisfaction. We propose the following relationship between role ambiguity and job satisfaction. H3c. Role ambiguity has a direct, negative effect on job satisfaction. 3.8. Promotion opportunities Promotion opportunities refer to the presence of a career path leading to a series of promotions and new positions within the current organization (London, 1983; Rhodes and Doering, 1983). Mowday et al. (1982) note promotion opportunity as one of the characteristics inuencing affective responses such as job satisfaction. Lawler (1973) indicated that problems or concerns with promotion are factors that provide a major source of dissatisfaction for employees. Super and Minor (1987) reported that career development

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

123

and satisfaction with career path signicantly affect an individual's commitment and job satisfaction. Quarles (1994a) also found that satisfaction with promotion opportunities directly affects job satisfaction for internal auditors at both staff and supervisory level. We extend the relationship between promotion opportunities and job satisfaction to IS auditors. H4. Satisfaction with promotion opportunities has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. 3.9. Pay satisfaction Pay, in general, can be viewed as reward or outcome received by employees (Lum et al., 1998). For organizations, pay is a part of sanction systems used to motivate compliance with rules and regulations (Mueller and Price, 1990). According to equity theory (Adams, 1965), pay satisfaction/dissatisfaction is the result of perceptual and comparative processes of one's outcome/input ratio to some source of references. In a different way, Lawler (1971) dened pay satisfaction/dissatisfaction as the congruence/ incongruence between what individuals perceive they are paid and their perception of the amount they should be paid. Lawler (1971) argued that dissatisfaction with pay is likely to affect job dissatisfaction. Investigating the turnover intention of nurses, Lum et al. (1998) found that the effect of pay satisfaction on turnover intention is mediated by job satisfaction, and that pay satisfaction and job satisfaction are positively correlated. Couger et al. (1979) noted the importance of pay satisfaction to IS professionals. Their study observed little difference in the importance of pay satisfaction between IS and other technical professionals in their study. Accordingly, pay satisfaction would appear to provide a signicant inuence on IS auditor professionals. Hence, H5. Satisfaction with pay has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. 3.10. Personal growth needs The concept of growth needs originated from Maslow's (1943) need hierarchy theory. Need hierarchy maintains that as basic needs such as physiological needs are satised, we need to fulll increasingly higher-order needs such as growth needs. Growth needs are concerned with the need for personal development and realization of one's potential. Professionals involved with the information technology industry have high growth needs (Couger et al., 1979, 1992). In the same way, IS auditors, whose jobs are a unique amalgam of information technologies and auditing (Sia, 1999), are almost certain to have high growth needs. Consequently, IS auditors would likely insist that their job fulls their personal development needs. Hence, H6. Satisfaction with the fullment of personal growth needs has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. 4. Research method In this section we describe the method used to collect our data. We then discuss the instrumentation used to measure our independent variables. 4.1. Data collection Our study used a self-administered survey to collect data. We selected this method for four reasons. First, to validate the proposed model with a reasonable level of condence, this study required a relatively large amount of data. Second, given the subject matter of this study, a number of sensitive questions were asked of the participants. Generally, people tend to avoid answering sensitive questions unless they believe their condentiality and anonymity can be guaranteed. Without guarantees of anonymity, people are less likely to respond, or if they do, they likely give false information (Warner, 1965). Third, the sample population of this study is relatively homogenous, i.e., involving participants within one profession only. Wallace (1954) argued that in a homogenous population, results obtained from a survey might not much differ from those

124

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

obtained through other methods of inquiry. Fourth, this study is a quantitative investigation of turnover intention of IS auditors. A survey, therefore, is an acceptable approach for a quantitative study (Hunt, 1991; Malhotra, 1993; Cooper and Schindler, 2003). To help ensure this study accurately reected the turnover intentions of IS auditors, the participants of this study were members of the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA) in Australia. ISACA is the organization representing IT Governance professionals.

5. Instrumentation 5.1. Turnover intention To measure turnover intention, we used four items adapted from Mobley et al. (1978) and Lee (1996) (see Appendix A). The response options for these items were based on a seven-point rating scale ranging from not at all to all the time (one item) and extremely unlikely to extremely likely (three items). Regarding their turnover intentions, the respondents were asked to consider their likely actions in the six months from the date of the survey. Past studies on turnover have used different time periods to measure turnover intention varying from six months (Quarles, 1994a) to 1 year (Aranya and Ferris, 1984; Shore et al., 1990). Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) suggest that measuring the intention antecedent to behavior is more reliable if measured within a reasonable time frame. Considering Ajzen and Fishbein's contention, this study used a six-month period. Furthermore, using a six month period allows more direct comparisons with Quarles' (1994a) study.

5.2. Organizational commitment We measured Organizational commitment using the four-item short version of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire developed by Porter et al. (1974) (see Appendix A). This questionnaire is commonly regarded as the preeminent instrument of its type (Reichers, 1985) and has been widely used to study organizational commitment (Aranya and Ferris, 1984). The four items selected for this study were items that describe the three facets of organizational commitment as suggested by Porter et al. (1974), vis-vis, (1) a strong belief in, and acceptance of, the organization's goals and values; (2) a willingness to exert considerable effort on behalf of the organization; and (3) a denite desire to maintain organizational membership. The responses were measured using a seven-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

5.3. Job satisfaction Job satisfaction was measured using the Job Satisfaction Measure developed by Hoppock (1935) (see Appendix A). This instrument was used as it measures job satisfaction as an overall concept, the denition used in this study. Although Hoppock's (1935) instrument was developed some 70 years ago, it has been validated for contemporary use (Lee, 1996). The response options for the three items used were based on a seven-point verbally anchored response ranging from I hate it to I love it, Never to All of the time, and No one dislikes his/her job more than I dislike mine to No one likes his/her job better than I like mine.

5.4. Role conict and role ambiguity We measured Role conict and role ambiguity, respectively, using four items adapted from Rizzo et al. (1970) (see Appendix A). These items have been subject to extensive validation (Lee, 1996) and are widely used for measuring role related stress (Tubre and Collins, 2000). The responses to the items used were measured using a seven-point rating scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

125

5.5. Promotional opportunities Promotional opportunities was measured using four items developed by Curry et al. (1986) (see Appendix A). These four items required respondents to indicate their agreement/disagreement to several aspects of promotion policy in their respective organizations. The response options were based on a sevenpoint rating scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. 5.6. Pay satisfaction We measured Pay satisfaction using four items (see Appendix A). The rst three items asked respondents to evaluate their satisfaction with both the amount of pay and fringe benets they received from their organization and with the frequency and amount of pay rises. These items are commonly used to measure pay satisfaction (Smith et al., 1969; Hackman and Oldham, 1975). The fourth item was adapted from Lee (1996). It asked respondents to evaluate their satisfaction relative to being paid fairly for the work they contributed to their organization. The responses for all items were measured using a seven-point scale ranging from extremely dissatised to extremely satised. 5.7. Growth needs The variable growth needs was measured using ve items from the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman and Oldham, 1975) (see Appendix A). This measure is commonly used in organizational behavior literature (Lee, 1996). Taber and Taylor (1990) reported that the Job Diagnostic Survey has satisfactory psychometric qualities. The response options were based on a seven-point scale ranging from extremely dissatised to extremely satised. 5.8. Survey instrument Our web-based questionnaire was structured in two parts with 40 questions in total. The rst part comprised seven sections with 32 questions measuring the independent variables in the proposed model. The second part contained eight questions soliciting respondents' demographic and other background information. All questions were closed in nature. To record their responses, participants clicked on radiobuttons, entered a number, or entered other work-related information that best described their responses. 5.9. Data analysis We used Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) to evaluate the proposed model and then test the hypotheses. SEM is a second generation data analysis technique (Bagozzi and Fornell, 1982) that allows the researcher to analyze a set of interrelated hypotheses in a single, systematic, and comprehensive way (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). SEM is also a conrmatory technique, and is most often used when theory testing (Ullman, 2001). In this study, we sought to understand the factors that affect the turnover intention of IS auditors. A prerequisite of SEM is that users should have a prior knowledge, or hypotheses about the relationships among variables (Ullman, 2001). Given this study was informed by Quarles' (1994a,b) prior studies, we had rm beliefs about the relationship between the variables of interest. The following sections present conrmation of our model and our ndings. 6. Results We now present the results of the analyses used to test our model and the hypotheses we developed previously. The participant demographics are presented rst, followed by a conrmatory factor analysis, item reliability testing, and model evaluation. The results of our analyses relative to our hypotheses conclude the section.

126

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

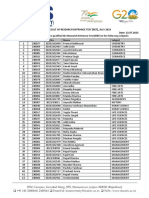

Table 1 Participant and organization characteristics. Panel A: Participants Male Female Audit background Internal auditor External auditor Position Auditor/IS auditor Senior auditor/Senior IS auditor Audit manager/IS audit manager Partner Missing data CISA qualied Number 105 26 93 38 21 41 58 5 6 86 Mean Audit experience (years) IS Audit experience (years) Panel B: Organizations Public accounting/management consulting Government agencies Others Missing data Organization size (number of staff) Less than 50 50100 101500 5011000 More than 1000 Missing data 11.19 9.05 Number 23 33 74 1 17 5 13 15 80 1 Proportion (80.2%) (19.8%) (71.0%) (29.0%) (16.0%) (31.3%) (44.3%) (3.8%) (4.6%) (65.6%) Std. Dev. 8.05 6.42 Proportion (17.6%) (25.2%) (56.5%) (0.8%) (13.0%) (3.8%) (9.9%) (11.5%) (61.1%) (0.8%)

6.1. Participant demographics We sent invitation-to-participate emails to 800 members of the participating ISACA Chapters. One hundred and forty responses were recorded in the database by the closing date. Of the 140 recorded responses, nine responses were deleted because they were incomplete. The total number of usable responses was 131 which represented an overall response rate of 16%. Table 1, Panel A, presents the characteristics of the 131 respondents included in the study, while Panel B presents the characteristics of their organizations. Table 1 shows that 71% of the respondents are internal auditors and 29% are external auditors. The majority of the respondents (78%) have middle to top-level positions in their organizations. More than half of the respondents (56%) work in organizations other than public accounting/management consulting and governmental agencies. They work in such areas as banking, nance, manufacturing, telecommunications, software development, and transportation. Also, more than half of the respondents (61%) work in large organizations (staff more than 1000). 6.2. Data checks: responses and distributions An independent group T-test was used to identify any signicant differences between early and late participants' responses. At 0.10 level of condence, there were no statistically signicant differences between early and late participants' responses. Among the 32 items surveyed, four items indicated nonnormal distributions. Data transformation was not used to remedy these items' non-normal distributions for two reasons. First, transformation is not universally recommended and should be considered and undertaken only when absolutely necessary (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001). Second, Busemeyer and Jones

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136 Table 2 Measurement model. Construct Turnover intentions Item TURNINT01 TURNINT02 TURNINT03 TURNINT04 COMMIT01 COMMIT02 COMMIT03 COMMIT04 JOBSAT01 JOBSAT02 JOBSAT03 RC01 RC02 RC03 RC04 RA01 RA02 RA03 RA04 PROM01 PROM02 PROM03 PROM04 PAY01 PAY02 PAY03 PAY04 GROWTH01 GROWTH02 GROWTH03 GROWTH04 GROWTH05 Estimate 1.51 1.96 1.96 1.44 0.50 0.82 1.51 1.49 1.78 1.12 0.82 0.99 1.26 1.18 1.09 1.07 0.92 1.14 1.25 1.15 1.36 1.65 1.84 1.35 1.41 1.49 1.55 0.99 1.06 1.28 1.49 1.06 t-value 14.34 21.78 19.34 10.70 3.97 4.92 13.33 12.54 11.26 12.78 8.06 6.76 8.54 7.32 6.16 7.99 6.73 10.23 11.11 7.79 8.41 13.41 21.10 12.92 14.53 19.41 20.24 7.52 8.24 10.14 15.31 8.32 Standardized Estimate 0.86 0.92 0.87 0.79 0.40 0.45 0.87 0.81 0.90 0.87 0.73 0.59 0.69 0.62 0.56 0.82 0.85 0.91 0.82 0.60 0.66 0.89 0.95 0.82 0.85 0.92 0.91 0.64 0.72 0.87 0.92 0.77

127

Standardized estimate squared 0.73 0.85 0.76 0.63 0.16 0.20 0.76 0.66 0.80 0.75 0.54 0.35 0.48 0.39 0.31 0.68 0.73 0.83 0.68 0.36 0.44 0.79 0.91 0.67 0.72 0.84 0.83 0.42 0.52 0.75 0.84 0.59

Organizational commitment

Job satisfaction

Role conict

Role ambiguity

Promotion opportunities

Pay satisfaction

Growth needs

(1993) argue that transformation may produce spurious effects in hierarchical regression analysis, making the results from the transformed data difcult to interpret (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2001).

6.3. Conrmatory analysis To examine whether the data met the hypothesized structure, a conrmatory analysis was performed. Table 2 presents the results of the conrmatory analysis. Using a 0.05 level of signicance with degrees of

Table 3 Construct reliability. Construct Turnover intentions Organisational commitment Job satisfaction Role conict Role ambiguity Promotion opportunities Pay satisfaction Growth needs Construct reliability 0.85 0.67 0.68 0.64 0.85 0.79 0.86 0.89 Variance extracted 0.59 0.36 0.42 0.30 0.58 0.50 0.61 0.62 Cronbach's 0.92 0.72 0.87 0.70 0.91 0.85 0.93 0.89

128

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

Table 4 Discriminant/Convergent validity 2 estimates matrix. Turnover Organisational Job Role Role Promotion Pay intentions commitment satisfaction conict ambiguity opportunities Turnover intentions Organisational Free model commitment Discriminant model Convergent model Job satisfaction Free model Discriminant Model Convergent model Role conict Free model Discriminant model Convergent model Role ambiguity Free model Discriminant model Convergent model Promotion Free model opportunities Discriminant model Convergent model Pay Free model Discriminant model Convergent model Growth needs Free model Discriminant model Convergent model 36.93 95.86 57.87 19.42 132.57 52.60 8.19 57.50 20.43 18.02 292.24 35.36 36.91 204.21 53.49 27.09 322.30 52.51 78.70 348.92 92.59 Growth needs

31.86 64.73 62.29 17.14 101.66 25.91 21.81 105.30 36.98 38.26 116.43 49.00 39.62 111.32 60.49 65.99 113.97 81.17

28.08 60.05 38.77 27.26 147.28 40.18 43.09 177.12 58.69 26.50 154.90 50.51 55.90 81.78 102.40

18.46 106.90 25.58 17.24 104.09 19.32 33.22 127.37 38.80 73.36 169.46 77.90

20.39 251.37 29.19 41.56 432.92 50.53 57.83 307.48 69.68

43.07 237.38 56.87 68.68 255.79 82.95

71.38 336.14 81.08

freedom N 100, all items have t-values greater than 1.96 (two-tailed). All items appear, therefore, to be unique and distinct. All items, their scales, and sources are listed in Appendix A.

6.4. Item selection and reliability test Rather than reduce the number of variables to improve the t of our model, we retained every parameter of our model. Furthermore, the number of responses obtained exceeded the minimum (100) required for LISREL (Hair et al., 1998). The constructs and their reliability coefcients are presented in Table 3. All constructs have reliability coefcients above the acceptable level of 0.60 (Nunnally, 1978; Schumacker and Lomax, 1996). To ensure our constructs reected the phenomena we were seeking to investigate, the constructs' average variance extracted and Cronbach's alpha were also measured. For the average variance extracted the v values of organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and role conict are below the suggested value of 0.50 (Hair et al., 1998). Although variance extracted for these constructs was lower than the suggested threshold, assessment of the measurement model reveals good evidence of reliability for the operationalization of the variables used in our study. The Cronbach alphas exceeded the 0.7 threshold (Hair et al., 1998). The items used were based on well-used and previously validated scales. When judging the sufciency of a model, Bollen and Long, (1993) suggest drawing on prior studies of the same or similar models is advantageous. Our overall model was based on Quarles' (1994a,b) models, both of which have been previously conrmed. To further ensure the constructs in our model were, indeed, distinct from one another we conducted a discriminant/convergent validity test. A free model was compared to two xed models, one for discriminant validity, and one for convergent validity. Table 4 shows that the free model tted better than either xed models thus indicating distinction between each of our constructs (Bagozzi et al., 1991). That is, for each combination of constructs in the matrix, the freely estimated model had a lower 2 indicating a better t than a model where correlations between each construct were xed to one (perfect correlation) or a model where correlations between each construct were xed to 0 (uncorrelated) (Bagozzi et al., 1991).

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

129

Fig. 2. The LISREL output of the model.

130 Table 5 Model t indices. Fit measure Absolute Incremental

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

Index Goodness-of-t index (GFI) Standardized Root mean squared residual (SRMR) Adjusted goodness-of-t index (AGFI) Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) Comparative Fit Index (CFI) Normed Chi-square (2/df)

Model value 0.76 0.008 0.71 0.96 0.96 1.37

Thresholds 0.90 below 0.05 0.90 0.90 0.90 Between 1.0 and 2.0

Parsimonious

Satorra and Bentler (1994) chi-square was used to mitigate possible effects of the non-normality associated with 4 of the 32 items surveyed.

6.5. Model evaluation There is a pervasive belief among MIS researchers that when sample size is small PLS is the most appropriate means of analyzing data (Goodhue et al., 2006, 2007). We have chosen not to use PLS for this study, LISREL remains our analysis tool of choice. As reported by Goodhue et al. (2006, 2007) in their comparison of LISREL, PLS and regression analyses, LISREL analyses, even at lower sample size, result in estimates that are closer to true values than the estimates obtained by using PLS or regression. Furthermore, this study seeks to test whether the high-level need, personal growth, particularly affects IS auditors' job satisfaction, and thus turnover intentions. As Anderson and Gerbing (1988) report, SEM is best suited to theory testing and development hence, LISREL again fullled our requirements. Following Byrne's (1998) suggestions, our study applied different criteria to assess the model t. The path diagram of the combined measurement and structural model obtained from LISREL are presented in Fig. 2. There are a multitude of t indexes described in the SEM literature (Kline, 1998). To further conrm the goodness of t of our model we present six of the more widely used indices (Kline, 1998) provided by LISREL. The index, the model values, and the generally applied thresholds are presented in Table 5. The widely accepted normed Chi-square (the ratio of the Chi-square to the degrees of freedom) (Kline, 1998; Bollen and Long, 1993; Schumacker and Lomax, 2004) is 1.37. The normed Chi-square is well within the typically accepted range of 1 to 2 (Ullman, 2001).3 While not all of our goodness of t indices fulll their respective thresholds, we believe that, overall, the goodness of t indices do indicate that our model ts well.4 Moreover, there is broad support, particularly in the applied research eld, for the view that relying on a single goodness of t index to support or, indeed, to discount a model is perilous (Kline, 1998; Bollen and Long, 1993; Schumacker and Lomax, 2004). In particular, Ullman (2001) reports that the more popularly reported model t indices are comparative t index (CFI) and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR). Our model comfortably exceeds the threshold values for both of these indices. To evaluate the structural model, our study focused on the relationships between the variables. This stage of the study tested whether the hypothesized relationships are supported by the data. Six of the nine hypotheses are supported by the data. The parameter estimates for each hypothesized relationship are

3 The Chi-square (2) of the model was 2 = 595.87; df = 436; p = 0.00. Ullman (2001) notes, however, that assessment of goodness of t is not always as straightforward as assessment of Chi-square. In particular, with small samples the probability level of the Chi-square may be inaccurate. Further, model complexity, i.e., the number of observed and latent variables, increases the likelihood of a signicant Chi-square. 4 To mitigate doubts over model t and to afrm our results, we conducted a bootstrapped PLS analysis of the fully dimensioned model. The results of that analysis conrmed, with the marginal exception of the effects of pay on job satisfaction, the signicance and direction of the constructs, and variance explained, as reported in the LISREL results of Table 6. The PLS results are presented in Appendix B.

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136 Table 6 Parameter estimates for the hypothesized relationships. Dependent variable TURINT COMMIT H1 H2a H2b H3a H3b H3c H4 H5 H6 Independent variable COMMIT JSAT JSAT RCONF RAMB RAMB PROMO PAY GROWTH Standardized coefcient (Beta) 0.37 0.38 0.55 0.21 0.19 0.04 0.05 0.23 0.75 Standard Error 0.174 0.126 0.172 0.095 0.094 0.096 0.070 0.085 0.099 t-statistic 2.15 3.05 3.20 2.24 2.00 0.37 0.67 2.74 7.60

131

R2 0.48 0.55

JSAT

0.74

Signicant at the 0.2 level, Signicant at the 0.05 level, Signicant at the 0.01 level.

presented in Table 6. The three independent variables, RCONF, PAY and GROWTH, correlate signicantly with the intervening variables COMMIT and JSAT in the hypothesized directions and relationships. Positive JSAT and COMMIT values are shown to have negative impacts on TURINT as originally hypothesized. Together, these variables explain 48% of the variance in TURINT. Our model explains 74% of variance in JSAT and 55% of variance in COMMIT. Indeed, our model explains a signicantly higher amount of the variance in JSAT (74%) than Quarles (1994a) model did with 54%. This result supports strongly the central argument of this paper that personal growth needs are critical to the IS auditor being satised with his/her job and thus reducing the likelihood of turnover. For comparison, the parameter estimates for each hypothesized relationship using PLS are presented in Appendix B. While the results are largely similar in terms of signicance and direction, the LISREL analysis yielded higher R2 values for the dependent variables. Three of the hypotheses were not supported. Role ambiguity, hypothesized as having a negative effect on organizational commitment had a marginally signicant positive effect (t-value = 0.19). Role ambiguity also had no signicant impact on job satisfaction. We did not anticipate these results as prior studies generally indicate role ambiguity negatively impacts both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. These unexpected results may be explained, however, by nearly half the respondents in our study (47%) holding middle to top-level positions (that is, IS audit managers and partners). Hamner and Tosi (1974) and Ilgen and Hollenbeck (1991) argue that individuals in such positions are likely to be the role-makers, i.e., although their jobs may be relatively more complex than other more clearly specied jobs, their roles are relatively clear. For them, role ambiguity likely forms part of the general uncertainty with which they routinely deal. By contrast, for less experienced IS auditors, role ambiguity and promotional opportunities may be more relevant to their views on organizational commitment and job satisfaction. To gain some insight on this view, we performed a test of the model on a subset of the data including just IS auditors and senior IS auditors. While role ambiguity and promotional opportunities were more important to this group, they remained insignicant in their effect on organizational commitment and job satisfaction, respectively. However, these results must be treated with caution due to the limited sample size.

Table 7 Summary of results. Hypothesis 1 2a 2b 3a 3b 3c 4 5 6 Relationships Organizational commitment has a direct, negative effect on turnover intentions. Job satisfaction has a direct, negative effect on turnover intentions. Job satisfaction has a direct, positive effect on organizational commitment. Role conict has a direct, negative effect on organizational commitment. Role ambiguity has a direct, negative effect on organizational commitment. Role ambiguity has a direct, negative effect on job satisfaction. Satisfaction with promotional opportunities has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. Satisfaction with pay has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. Satisfaction with the fullment of growth needs has a direct, positive effect on job satisfaction. Results Supported Supported Supported Supported Not supported Not supported Not supported Supported Supported

132

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

The results also provide no support for the hypothesis that satisfaction with promotional opportunities has a positive effect on job satisfaction. The seniority of the majority of the respondents likely explains this, apparently, counterintuitive nding. Further examination of the effect of promotional opportunities on other dependent variables, TURINT and COMMIT, found no statistically signicant relationship. The contention that lack of promotion opportunities is one of the factors explaining the high turnover rate of IS auditors was not supported (see e.g., Gallegos 1991; Dunmore, 1989; Tongren, 1994). Perhaps, unlike general accountants and auditors, the high personal growth needs of the technically oriented IS auditors outweigh signicantly the need for promotional opportunities to retain IS auditors. 7. Summary and future work The results of our study, summarized in Table 7, indicate that the factors affecting IS auditors' turnover intentions are role conict, satisfaction with pay, and fulllment of growth needs. These factors are moderated by organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Role conict has negative relationships with organizational commitment, while satisfaction with pay and fulllment of growth needs have positive relationships with job satisfaction. The analyses also indicate that job satisfaction has positive relationships with organizational commitment. Both the intervening variables have direct negative effects on the turnover intentions. Of the three independent variables affecting IS auditors' turnover intentions, both directly and indirectly, the fulllment of growth needs exerts the strongest inuence. This nding indicates that IS auditors' intentions to stay or leave their current organization are affected strongly by how well the organization can satisfy the IS auditors' needs for growth and personal development. Furthermore, this nding shows that IS auditors share a similar characteristic with other IS professionals. It may also indicate the possibility that IS auditors' need for growth and personal development is more acute than that of general accountants or auditors. In this way our model provides an important contribution to practice. Organizations wanting to retain their IS auditors must provide for their personal growth needs by, for example, presenting them with regular opportunities to learn about new technologies and their impact on IS audit. When considering the implications of our study, readers should be mindful of two points. First, the number of data cases used to analyze the model and test the hypotheses was relatively small. The ndings of our study, therefore, should be applied to all IS auditors with caution. Several data items indicated nonnormal distributions; non-normal data were retained in the analyses, however, due to difculties associated with interpreting results based on transformed data. Jreskog and Srbom (1993) report that departures from normality tend to increase Chi-square over and above what can be expected due to specication error in the model. Accordingly, assuming the data are normal means that the degree of model t may be overstated. Second, some demographic characteristics of interest are not evenly distributed. As noted, the typical respondent included in this study was a male internal auditor, who held a middle to top-level position in the organization. We argue that, on average, this description of IS auditors is representative of IS auditors in organizations (c.f. demographics of Quarles's 1994a,b studies). To help improve the external validity of our study, replication in other settings would be useful. Future research could include more extensive qualitative research to identify variables that help improve our model's explanatory power. Some of the factors that could usefully be pursued include organizational culture, demand from competing elds, need for change, dissatisfaction with management and one's assigned scope of work, and the reputation of other companies. Moreover, future research could fruitfully consider the apparent conict between the results in this study and Quarles' (1994b) study, in particular, the relationship between role ambiguity and the turnover intention of Information Systems auditors. Acknowledgements The authors gratefully acknowledge comments on earlier versions of this paper by Iris Vessey, and participants at workshops at the University of Queensland.

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

133

Appendix A

Surveyed item Operationalization TURNINT01 How often have you thought of quitting your job sometime in the next six months? 1 = Not at all; to 7 = All the time How do you feel about the following statement: I intend to quit my job in the next six months? 1 = Extremely unlikely; to 7 = Extremely likely How do you feel about the following statement: I will actively look for a new job in the next six months? 1 = Extremely unlikely; to 7 = Extremely likely b How would you rate your chances of still working for your current organization six months from now? 1 = Extremely unlikely; to 7 = Extremely likely I am willing to put in a great deal of effort beyond that normally expected in order to help my organization be successful. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly Agree I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for my organization. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly Agree I nd that my values and the organization's values are very similar. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly Agree For me, my current organization is the best possible organization for which to work. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly Agree Considering every aspect of your job, choose one of the answers that best tells us how well you like your job: 1 = I hate it; to 7 = I love it Considering every aspect of your job, choose one of the answers that shows how much of the time you feel satised with your job: 1 = Never; to 7 = All of the time Click ONE of the following to show how you think you compare with other people: 1 = No one dislikes his/her job more than I dislike mine; to 7 = No one likes his/her job better than I like mine I have to ignore a rule or policy in order to carry out an assignment. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I receive incompatible requests from two or more people. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I do things that are apt to be accepted by one person and not accepted by others. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I receive assignments without adequate resources, materials, and skills to execute them. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I have clear, planned goals and objectives for my job. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I know what my responsibilities are. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I know exactly what is expected of me. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree I have clear explanations of what has to be done. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree Promotions are regular. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree b I am in a dead-end job. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree

a

Number of items and source Four items: three items adapted from Quarles (1994b) and one item adapted from Lee (1996). Originally adapted from Mobley et al. (1978), four items

TURNINT02

TURNINT03

TURNINT04

COMMIT01

Four items: adapted from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire developed by Porter et al. (1974). Items from a different source than used by Quarles (1994b)

COMMIT02

COMMIT03

COMMIT04

JSAT01

Three items: adapted from Quarles (1994b). Originally adapted from Hoppock's (1935) Job Satisfaction Measures, four items

JSAT02

JSAT03

RCONF01

Four items: adapted from Quarles (1994b), eight items. Originally adapted from Rizzo et al. (1970), fteen items.

RCONF02 RCONF03

RCONF04

RAMB01 RAMB02 RAMB03 RAMB04 PROMO01 PROMO02

Four items: adapted from Quarles (1994b), six items. Originally adapted from Rizzo et al. (1970), fteen items.

Four items: adapted from Curry et al. (1986). Items not surveyed by Quarles (1994b)

(continued on next page)

134

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

Appendix (continuedA ) (continued) Surveyed item Operationalization PROMO03 PROMO04 PAY01 There is opportunity for advancement. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree There is good opportunity for advancement. 1 = Strongly disagree; to 7 = Strongly agree How satised are you with the amount of pay and fringe benets you receive? 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised How satised are you with the frequency of pay rises? 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised How satised are you with the increase in pay that you receive from pay rises in your organization? 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised How satised are you that you are paid fairly for the work you contribute to your organization? 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised Opportunities for personal growth and development on the job. 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised Chances to exercise independent thought and action in my job. 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised Stimulating and challenging work. 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised A sense of worthwhile accomplishment in my work. 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised Opportunities to learn new things from my work 1 = Extremely dissatised; to 7 = Extremely satised Number of items and source

Four items; three items adapted from prior research and one item adapted from Lee (1996). Items from a different source than used by Quarles (1994b)

PAY02 PAY03

PAY04

GROWTH01

Five items; adapted from Hackman and Oldhams's (1975) Job Diagnostic Survey. Items not surveyed by Quarles (1994b)

GROWTH02

GROWTH03 GROWTH04 GROWTH05

a b

This item has a different scale from other items in the same measurement instrument. Reverse-coded item.

Appendix B. PLS parameter estimates for the hypothesized relationships

Dependent variable TURINT COMMIT H1 H2a H2b H3a H3b H3c H4 H5 H6

Independent variable COMMIT JSAT JSAT RCONF RAMB RAMB PROMO PAY GROWTH

Path coefcient 0.32 0.39 0.51 0.15 0.19 0.02 0.12 0.15 0.63

Standard Error 0.121 0.124 0.080 0.071 0.077 0.056 0.072 0.085 0.083

t-statistic 2.63 3.17 6.44 2.06 2.56 0.39 1.66 1.80 7.56

R2 0.41 0.45

JSAT

0.57

Signicant at the 0.05 level, Signicant at the 0.01 level.

References

Abelsen MA. Examination of avoidable and unavoidable turnover. J Appl Psychol 1987;71(3):3826. Adams JS. Injustice in social exchange. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. New York: Academic Press; 1965. Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviors. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall; 1980. Alderfer C. An empirical test of a new theory of human needs. Org Behav Hum Perform 1969;4:14275. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 1988;103(3):41123. Aranya N, Ferris KR. A reexamination of accountants' organizational-professional conict. Account Rev 1984;59:1-15. Arnold HJ, Feldman DC. A multivariate analysis of the determinants of job turnover. J Appl Psychol 1982;67:35060.

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

135

Bagozzi RP, Fornell C. In: Fornell C, editor. Theoretical concepts, measurement, and meaning. A Second generation of multivariate analysis. Praeger: New York; 1982. Bagozzi RP, Yi Y, Phillips LW. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm Sci Q 1991;36(3):42158. Bagranoff NA, Vendrzyk VP. The changing role of IS audit among the big ve US-based accounting rms. Inf Syst Control J 2000;5:337. Baird LL. A study of the role relations of graduate students. J Educ Psychol 1969;60(1):1521. Benke RL, Rhode JG. The job satisfaction of higher level employees in large certied public accounting rms. Account Organ Soc 1980;5 (2):187201. Bluedorn AC. The theories of turnover: causes, effects, and meaning. Res Sociol Organ 1982;1:75-128. Bollen KA, Long JS. Introduction. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. Busemeyer JR, Jones EL. Analysis of multiplicative combinations rules when the causal variables are measured with error. Psychol Bull 1993;93(3):54962. Business Week. Getting in at Ernst & Young. MBA insider: Recruiter Q&A July 15, 2008; 2008. URL: http://www.businessweek.com/ bschools/mbapremium/jul2008/bs20080715_587369.htm Accessed 24 November. Byrne BM. Structural equation modelling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1998. Cooper DR, Schindler PS. Business research methods. 8th Ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill/Irwin; 2003. Cotton JL, Tuttle JM. Employee turnover: a meta-analysis and review with implications for research. Acad Manag Rev 1986;11:5570. Couger JD, Opperman EB, Amoroso DL. Motivating Information Systems managers in the 1990s. Inside DPMA 1992;vol. 5:69. Couger JD, Zawacki RA, Opperman EB. Motivation level of MIS managers versus those of their employees. MIS Q 1979;3(September):4756. Curry JP, Wakeeld DS, Price JL, Mueller CW. On the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Acad Manage J 1986;29(4):84758. Dunmore DB. Farewell to the information systems audit profession. Intern Audit 1989:428 February. Dunn PA. The cost of turnover. Pins Needles 1995;32(July):24. Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. Gallegos F. Computer information systems audit career development. EDP Audit J 1991;I:2331. Goodhue DL, Lewis W, Thompson RL. PLS, small sample size, and statistical power in MIS research. Proceedings of the 39th. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Kauai, Hawaii, IEEE; 2006. p. 202b. Goodhue DL, Lewis W, Thompson RL. Statistical power in analyzing interaction effects: questioning the advantage of PLS with product indicators. Inf Syst Res 2007;18(2):21127. Gregson T. Communication satisfaction: a path analytic study of accountants afliated with CPA rms. Behav Res Account 1990;2:3249. Gregson T. An investigation of the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in turnover models in accounting. Behav Res Account 1992;4:8095. Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Development of the job diagnostic survey. J Appl Psychol 1975;60(2):15970. Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis. 5th Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1998. Hamner WC, Tosi HL. Relationship of role conict and role ambiguity to job involvement measures. J Appl Psychol 1974;59:4979. Harrel AM, Stahl MJ. McClelland's trichotomy of needs theory and the job satisfaction and work performance of CPA rm professionals. Account Organ Soc 1984;9(3/4):24152. Harrell A, Chewning E, Taylor M. Organizationalprofessional conict and the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of Internal Auditors. Audit: J Prac Theory 1986;5:10921. Herzberg F. The motivation to work. New York: Wiley; 1959. Hitt MA, Black JS, Porter LW. Management. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 2005. Hoppock R. Job satisfaction. New York: Harper and Brothers, Arno Press; 1935. Hunt S. Modern marketing theory: critical issues in the philosophy of marketing science. Cincinnati, OH:: South-Western Pub; 1991. Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR. The structure of work: job design and roles. In: Dunnette MD, Hough LM, editors. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, vol. 2. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1991. Ironson GH, Smith PC, Brannick MT, Gibson WM, Paul KB. Construction of a job in general scale: a comparison of global, composite, and specic measures. J Appl Psychol 1989;74(2):193200. Jackson SE, Schuler RS. A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conict in work settings. Org Behav Hum Decis Process 1985;36(1):1678. Jreskog KG, Srbom D. LISREL 8: user's reference guide. Hillsdale, NJ: Scientic Software International; 1993. Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA. Organizational stress. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1964. Katz D, Kahn RL. The social psychology of organizations. (2nd Ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1978. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1998. Lawler EE. Pay and organizational effectiveness: a psychological view. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1971. Lawler EE. Motivation in work organizations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.; 1973. Lee P.C.B., 1996. An investigation of the turnover intentions of Information Systems Staff in Singapore. Thesis, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD. Locke E. The nature and consequences of job satisfaction. In: Dunnette M, editor. Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally College; 1976. Locke EA, Latham GP. A theory of goal setting and task performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1990. London M. Toward a theory of career motivation. Acad Manage Rev 1983;8(4):62030. Lucy R.F., Factors affecting information systems audit resource allocation decisions. Thesis, The University of Texas, Arlington, 1998. Lucy RF. IS auditing: the state of the profession going to the 21st century. IS Audit Control J 1999;IV:4450. Lum L, Kervin J, Clark K, Reid F, Sirola W. Explaining nursing turnover intent: job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, or organizational commitment? J Organ Behav 1998;19:30520. Malhotra N. Marketing research: an applied orientation. 2nd Ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1993. Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943;50(4):37096. Meixner WF, Bline DM. Professional and job-related attitudes and the behaviors they inuence among governmental accountants. Account Audit Account J 1989;2(1):8-20.

136

A.D. Muliawan et al. / International Journal of Accounting Information Systems 10 (2009) 117136

Michaels C, Spector P. Causes of employee turnover: a test of the Mobley, Grifth, Hand and Meglino model. J Appl Psychol 1982;67:539. Miller HE, Katerberg R, Hulin CL. Evaluation of the Mobley, Horner, and Hollingsworth model of employee turnover. J Appl Psychol 1979;64:50917. Mobley W. Employee turnover: causes, consequences, and control. Reading MA: Addison-Wesley; 1982. Mobley WH, Grifth RW, Hand HH, Meglino BM. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol Bull 1979;86:493522. Mobley WH, Horner SO, Hollingsworth AT. An evaluation of the precursors of hospital employee turnover. J Appl Psychol 1978;63 (4):40814. Mowday RT, Porter LW, Steers RM. Employeeorganization linkages: the psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press; 1982. Muchinsky PM, Morrow PC. A multidisciplinary model of voluntary employee turnover. J Vocat Behav 1980;17:26390. Mueller CW, Price JL. Economic, psychological and sociological determinants of voluntary turnover. J Behav Econ 1990;19(3):32135. Nunnally J. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. O'Connor D, Yballe L. Maslow revisited: constructing a road map of human nature. J Manag Educ 2007;31(6):73856. Organ DW, Green CN. The effects of formalization on professional involvement: a compensatory process approach. Adm Sci Q 1981;26:23752. Podsakoff PM, Williams LJ, Todor WD. Effects of organizational formalization on alienation among professionals and non professionals. Acad Manage J 1986;29(4):82031. Porter LW, Steers RM, Mowday RT, Boulian PV. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J Appl Psychol 1974;59:6039. Quarles R. An examination of promotion opportunities and evaluation criteria as mechanisms for affecting internal auditor commitment, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. J Manag Issue 1994a;6(2):17694. Quarles R. An empirical examination of a model of turnover intentions of information systems auditors. J Appl Bus Res 1994b;10 (Winter):7385. Rasch RH, Harrell AM. The impact of personal characteristics on the turnover behavior of accounting professionals. Audit J Pract Theory 1990;9(Spring):20115. Reichers AE. A review and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Acad Manage Rev 1985;10(3):46576. Rhodes SR, Doering M. An integrated model of career change. Acad Manage Rev 1983;8(4):6319. Rizzo JR, House RJ, Lirtzman SI. Role conict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Adm Sci Q 1970;15(2):15063. Roth PG, Roth PL. Reduce turnover with realistic job previews. CPA J 1995;65(9):689. Satorra A, Bentler PM. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: von Eyeand A, Clogg CC, editors. Latent variables analysis: applications for developmental research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications; 1994. Scarpello V, Campbell JP. Job satisfaction: are all the parts here? Pers Psychol 1983;36:577600. Schaubroeck J, Cotton JL, Jennings KR. Antecedents and consequences of role stress: a covariance structure analysis. J Organ Behav 1989;10:3558. Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner's guide to structural equation modelling. edn 1. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1996. Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner's guide to structural equation modelling. edn 2. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 2004. Senatra PT. Role conict, role ambiguity, and organizational climate in a public accounting rm. Account Rev 1980;55(4):594603. Shore LM, Newton LA, Thorton GC. Job and organizational attitudes in relation to employee behavioral intentions. J Organ Behav 1990;11(1):5767. Sia SK. Surfacing the career development issues of IS auditors: the myths and the reality; 1999. Information Systems Audit and Control Association InfoBytes (http://www.isaca.org/Template.cfm?Section=Publications1&CONTENTID=7899&TEMPLATE=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfmaccessed on 2 April 2004). Smith P, Kendall L, Hulin C. The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago: Rand; 1969. Sorensen JE. The behavioral study of accountants: a new school of behavior research in accounting. Manage Decis Econ 1990;11:327441. Steel RP, Ovalle NK. A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. J Appl Psychol 1984;69(4):67386. Steers RM. Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment. Adm Sci Q 1977;22:4656. Stevens JM, Beyer JM, Trice HM. Assessing personal, role, and organizational predictors of managerial commitment. Acad Manage J 1978;21(3):38096. Super D, Minor F. Career development and planning in organizations. In: Bass B, Drenth J, editors. Advances in organizational psychology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1987. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th Ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. Taber TD, Taylor E. A review and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Pers Psychol 1990;43 (3):467500. Tongren J. Career planning for IS auditors. IS Audit Control J 1994;I:8-11. Tubre TC, Collins JM. Jackson and Schuler (1985) revisited: a meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conict, and job performance. J Manage 2000;26(1):15569. Ullman JB. Using multivariate statistics. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Structural equation modeling. 4th Ed. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. Wallace D. A case for- and against-mail questionnaires. Public Opin Q 1954;18(1):4052. Warner SL. Randomized response: a survey technique for eliminating evasive answer bias. J Am Stat Assoc 1965;60(309):639. Watson DJH. The structure of project teams facing differentiated environments: an exploratory study in public accounting rms. Account Rev 1975;50(April):25973. Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW, Lofquist LH. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, Minnesota Studies in Vocational Rehabilitation, XXII. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Industrial Relation Centre; 1967. Williams LJ, Hazer JT. Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: a reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. J Appl Psychol 1986;71(2):21931.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Auditing in Enterprise System Environment: A Synthesis: Jeim 24,6Dokumen26 halamanAuditing in Enterprise System Environment: A Synthesis: Jeim 24,6Daniel KhawBelum ada peringkat

- Computerised Accounting Information Systems Lessons in State-Owned Enterprise in Developing Economies PDFDokumen23 halamanComputerised Accounting Information Systems Lessons in State-Owned Enterprise in Developing Economies PDFjcgutz3Belum ada peringkat

- P. Accounting & F.M Assignment.Dokumen11 halamanP. Accounting & F.M Assignment.Oneof TNBelum ada peringkat

- Enterprise Systems and The Re-Shaping of Accounting Systems: A Call For ResearchDokumen6 halamanEnterprise Systems and The Re-Shaping of Accounting Systems: A Call For ResearchAboneh TeshomeBelum ada peringkat

- Risk-Based Audit Planning For Beginners - ISACA JournalDokumen7 halamanRisk-Based Audit Planning For Beginners - ISACA JournalRilo WiloBelum ada peringkat

- The Impact of Information Technology On Internal Auditing PDFDokumen17 halamanThe Impact of Information Technology On Internal Auditing PDFIndra Pramana100% (2)

- The Effect of Information Technology On Human Resource Management As A Strategic Tool in An OrganisationDokumen48 halamanThe Effect of Information Technology On Human Resource Management As A Strategic Tool in An OrganisationfredalfBelum ada peringkat

- Computerized Personnel Management System SoftwareDokumen66 halamanComputerized Personnel Management System SoftwareOkaroFrank100% (2)

- CAIS lessons from Ghanaian SOEsDokumen24 halamanCAIS lessons from Ghanaian SOEsMoHamed M. ScorpiBelum ada peringkat

- Complementary Controls and ERP Implementation SuccessDokumen23 halamanComplementary Controls and ERP Implementation Successtrev3rBelum ada peringkat

- A Financial Services OrganizationDokumen11 halamanA Financial Services OrganizationMaritsa AmaliyahBelum ada peringkat

- A Comparative Analysis of The Effectiveness of Internal Control System in A Computerized Accounting SystemDokumen71 halamanA Comparative Analysis of The Effectiveness of Internal Control System in A Computerized Accounting SystemDaniel ObasiBelum ada peringkat

- IT Governance Organizational Capabilities ViewDokumen5 halamanIT Governance Organizational Capabilities ViewEbstra EduBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Computerised Accounting Systems On Audit Risk 2013 PDFDokumen10 halamanEffect of Computerised Accounting Systems On Audit Risk 2013 PDFHasmiati SBelum ada peringkat

- Accounting Information SystemDokumen7 halamanAccounting Information SystemChime Lord ChineduBelum ada peringkat

- Opportunities For Artificial IntelligenceDokumen10 halamanOpportunities For Artificial IntelligenceMatthew ReeceBelum ada peringkat

- Project Synopsis: ERP ImplementationDokumen6 halamanProject Synopsis: ERP ImplementationAchal Kumar0% (1)

- Literature Review On Internal Audit and ControlDokumen5 halamanLiterature Review On Internal Audit and Controlttdqgsbnd100% (1)

- A Review of IT GovernanceDokumen41 halamanA Review of IT GovernanceAdi Firman Ramadhan100% (1)

- Sources of Error in Survey and Administrative Data - Importance of Reporting ProcedureDokumen26 halamanSources of Error in Survey and Administrative Data - Importance of Reporting ProcedureFIZQI ALFAIRUZBelum ada peringkat