Holsti War Peace and The State of The State

Diunggah oleh

Barnabe BarbosaDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Holsti War Peace and The State of The State

Diunggah oleh

Barnabe BarbosaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

War, Peace, and the State of the State Author(s): K. J.

Holsti Reviewed work(s): Source: International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, Vol. 16, No. 4, Dangers of Our Time. Les dangers de notre temps (Oct., 1995), pp. 319-339 Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1601353 . Accessed: 29/04/2012 10:41

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique.

http://www.jstor.org

Political ScienceReview (1995), Vol. 16, No. 4, 319-339 International

War, Peace, and the State of the State

KJ. HOLSTI

ABSTRACT. Against the tenets of realist literature, the article argues that the main source of war in the last half-century is internally-derived, and resides in the nature of post-1945 states. Regional and temporal variations in the topography of war make suspect realist claims of state similarity and systemic explanations of war. It is not the security dilemma nor the international system, but the composition of state legitimacy and the characteristic of weak, strong, and failed states which explain war today. Regions populated by strong states, defined in terms of legitimacy, are arenas of peace, and regions of weak and failed states are a prime location of war.

War, according to the realist literature in international relations, is a "dismaying" (Waltz, 1979: 66), recurrent, and necessary outcome of the operations of anarchical state systems. Hobbes and Rousseau were among the first to outline the external consequences of sovereign statehood, namely, that the means by which states seek to enhance their security in a self-help system necessarily cause insecurity and ultimately war among their neighbors. Threats to the state are thus externallyderived. I argue that the main source of war in the last half-century resides not in the anarchical character of the state system, but rather in the nature of post-1945 states. The more general claim is that regions populated by strong states, defined in terms of legitimacy, are a necessary condition for peace, and that regions of weak and failed states are a prime location of war. The theoretical platform for this exercise is Kenneth Waltz's claim that states are similar in the tasks and functions they perform. He acknowledges that they have different capacities to perform them, but otherwise they are comparable. All states, for example, seek survival and all the things that go into the broad concept of the population's "welfare," namely education, employment, trade, commerce, and the like. The essay also relates to Karl Deutsch's work (1957) on national and international integration. It is because the active units of international politics are functionally similar that the outcomes of their interactions fall within predictable patterns and recurrence.

0192-5121 95/04 319-21 ? 1995 International Political Science Association

320

War,Peace,and the State of the State

Whatever the unique properties of individual states of their policy-makers, the characteristics of the system, as in a market, "force"the units to behave in certain ways. The essential quality of international politics in an anarchical system is therefore the same, regardless of historical era. "The texture of international politics," writes Waltz (p.66), "remains highly constant, patterns recur, and events repeat themselves endlessly. [Events] are marked ... by dismaying persistence, a persistence that one must expect so long as none of the competing units is able to convert the anarchic international realm into a hierarchic one." The most dismaying recurrence of an anarchical system is war. Waltz follows Hobbes's and Rousseau's argument that the price for creating the state to obtain its domestic advantages is external insecurity and war. He similarly accepts Rousseau's argument that whatever the differing characteristics of individual states, they are commonly in a relation of mistrust, insecurity, and conflict, and thus frequently resort to arms. If the realist theoretical analysis is valid-patterns "dismayingly"repeating themselves-we would expect to see war occurring with somewhat similar frequency regardless of locale and historical context. Most theorists agree that we live in an essentially anarchic system. But the claims that all units are functionally similar and that the outcomes of interaction are drearily repetitive are certainly open to critical inquiry. It is not legitimate to argue, as does Waltz, that a theory of international politics is a theory only of the great powers. For if the entire system is characterized by anarchy, then the repetitious outcomes of wars and balances of power should be observed whenever sovereign states interact, regardless of their capabilities. To argue otherwise implies that the from other states, and that there are important great powers arefunctionally different distinctions, other than capabilities, between the units of an international system. Neither Rousseau nor Waltz accepts the proposition that unit level differences bring different systemic outcomes. The quality of international life is always the same, and will remain so as long as the anarchical principle underlies the international system. But if there are significant variations in the patterns of war and other outcomes between different regions and across time, then both the claim for state similarity and for a systemic explanation of war become suspect. The Rousseauistic structural explanation of war stands or falls on the claim of similarity of and among units. War was the problem that animated Karl Deutsch's life-long work on integration. It was because of his normative concern with war that he re-directed research to the conditions of peace. To him, the medium for the peaceful conditionwas integrationbetween individuals, communities, and nations. His problematic was to identify the necessary and sufficient conditions for integration. Lurking behind the work was the assumption that integration is progressive because true communities incorporate conflict-resolvinghabits and mechanisms that preclude armed conflict. One of the key indicators of international integration is the absence of plans for or deployments of military capabilities toward partners in a "pluralisticsecurity community." While Deutsch agreed that integration is neither a linear process nor inevitable, his work reflected the Eurocentric and teleological thrust of integration theory in the 1950s and 1960s. Opposition to integration, fragmentation, and the collapse of community were not part of his research agenda. Yet, war today is rooted in the lack, or disintegration of, community within states. The Topography of War Since 1945 Hobbes and Rousseau characterized the relations between European states as a

TABLE 1. ArmedConflictsby Typeand Region, 1945-1995. Type Africa Central America/ Caribbean 6 1 10 17 11 65% Eastern Europe/ Balkans 2 2 1 5 3 60% Western Europe 0 1 1 2 2 100% South America 1 0 10 11 10 91% Former USSR 1 6 3 10 9 90%

Middle Sou As East 12 9 9 30 18 60% 5 8 4

State v. state/ intervention Internal resistance/ secession Internal ideological Total Of which internal Percent internal

21 27 14 62 41 66%

17 12

71%

322

War,Peace,and the State of the State

"state of war." This did not mean that war was ubiquitous in every neighborhood, but that states always had to be on guard. Or, as Morgenthau put it later, states are always preparing for war, engaging in war, or overcoming the effects of the last war. Even allowing for the possibility that there could be "islands of peace," or short eras of relaxed tension, the incidence of war in Hobbes's and Rousseau's Europe was sufficient to justify their pessimism. Although numbers differ according to various studies, the dimensions of the problem are approximately the same. In previous work (Holsti, 1991), I identified 119 wars among Europe's small number of states between 1648 and 1945, or one war starting on average every 2.5 years. Little wonder that a theorist seeking an explanation would be impressed by the dreary repetitiveness of conflicts, crises, peace conferences, and more armed conflicts. Wars were a permanent feature of the European landscape. Nor has the situation improved radically in other locales since 1945. Table 1 lists a total of 187 internal and interstate wars/interventions between 1945 and 1995. When we adjust for the larger number of states in the system, however, the incidence of war varies substantially between different historical periods. In the 1648-1713 period, for example, the probabilityof any state's going to war in a given year was one in forty. For the 50 years since 1945, the risk of involvement in international war or armed intervention for a typical state-assuming an average of 125 states in the period-declined to slightly less than one in one hundred. The supposedly recurrent outcome of anarchy changes significantly over time. When we break down locales of war, moreover, even greater variations-indeed anomalies-appear. There has been no interstate war in Western Europe since 1945; none in North America since 1913-1915 (American armed intervention in Mexico); in South America only the Falklands War-and that was against an extra-regional power-since the Peru-Ecuador conflict of 1941. Clearly something is not happening in these areas that, according to realist predictions, should be happening. Tables 1 and 2 provide some data on the location and types of war since 1945. Since so many quantitative studies of war use different data and different criteria for inclusion, I claim no precision. The data reported here come from a variety of standard sources. Other recent studies (Arnold, 1991; Nietschmann, 1987) are unreliable because no criteria for inclusion are indicated, or they are methodologically reliable but somewhat dated (Small and Singer, 1982). Table 1 shows the locales of war since 1945. Armed contests have been ubiquitous in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. There has been no international war (i.e., two or more armies in armed combat for the purpose of inflicting military defeat and extracting terms of victory) or massive armed intervention in Western Europe and North America, and no war between states in South America since 1941. The figures also show that more than two-thirds of all armed combat in the world since 1945 has taken the form of civil wars, wars of state against nation, wars of secession, and major armed uprisings to oust governments. These are internal wars. Nietschmann (1987: 7) suggests an even higher figure: 72 percent of all wars were of the national disintegrative rather than the classical state-state variety. Both figures are consistent with the argument of this article: most threats to post-1945 states have been internal, not external. The case is even stronger when we consider that many of the interstate wars and large armed interventions originated as civil disturbances and wars. Hungary 1956, the Dominican Republic 1965, and India-Pakistan 1971, are just some of the examples. Indeed, of twoor more combats the 187 wars listed in Table 1, only30 wereclassicalarmed involving war That an incidence of interstate armies states. is organized of internationally-recognized

KJ. HOLSTI TABLE 2. ArmedConflicts per State by Region,1945-1995. Region Africa Central America/ Caribbean Eastern Europe/ Balkans Western Europe South America Former USSR Middle East South Asia Southeast Asia East Asia Average No. of States 43 20 8 18 12 15 18 7 11 6 Interstate, Interventions .49 .30 .25 .00 .08 .07 .67 .71 .73 .33 .36

323

Internal Wars .95 .55 .38 .11 .83 .60 1.00 1.71 1.64 .83 .86

once every 1.8 years-higher than in the seventeenth century, but when we normalize for the number of states in the system, a remarkable decline. Table 2 normalizes the frequency of wars according to the number of states in a region. We would expect more wars where there are more states, but according to realist predictions, normalized figures should be similar across regions. However, the figures in Table 2 show dramatic differences between regions. War since 1945 has been highly concentrated in the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Internal wars have a different profile. South America ranks fourth highest, while sub-Saharan Africa and Central America/Caribbean are well below the average. However we interpret such figures, Western Europe and North America are obvious anomalies. South America is an anomaly in terms of international war, but comes closer to the profile of other Third World areas when it comes to domestic armed strife. The overall pattern of war since 1945, then, does not duplicate European patterns from 1648 to 1945. There has been considerably less interstate war, considerably more war originating from civil disturbances, and war incidence of both types has varied widely according to locale. Other artifacts of a system of anarchy do not fare better in post-1945 international politics. Duplication of past European patterns would include hegemonyseeking, alliances, balances of power, and arms races, all accoutrements of European diplomatic history and realist analysis. Hegemony-seeking has been prominent only in the Middle East and arguably in South Asia. It is absent in subSaharan Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. Formal alliances among Third World and post-Communist states are conspicuous by their rarity. Today, there is none in South America, Southeast Asia, Africa, or South Asia; they have been prominent only in the Middle East. Nor do we find Waltz's ubiquitous balances of power. There is none today in South America (Selcher, 1990: 95), Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia, or the former Soviet Union despite the fact that in each of these regions there are predominant states (Brazil, Nigeria, India, Indonesia, and Russia). If there has been balancing, it has been between regional states and a super-power (e.g., the United States and Pakistan). The argument is unconvincing that the cold war balance of power makes regional balances unnecessary, since we have not seen

324

War,Peace,and the State of the State

balancing behavior emerge in those regions since 1989. Again, only in the Middle East do we see some duplication of pre-1945 patterns of European behavior. Even that common trait of European politics, the border dispute, has been rare in Africa (Herbst, 1989), leading Robert Jackson and Carl Rosberg (1982: 21) to argue that

in ... Black Africa, an image of international accord and civility and internal disorder and violence would be more accurate .... It is evident that the recent national and international history of Black Africa challenges more than it supports some of the major postulates of international relations theory. And perhaps most fundamentally, the realists' famed "security dilemma," leading to cycles of competitive arming, does not find empirical corroboration in many Third World neighborhoods (for evidence, see McKinlay, 1989: ch. 8). Security threats, in other words, are primarily domestic rather than external. These findings suggest that if we wish to understand the etiology of armed conflict in the post-Communist states and the Third World, approaches deriving from the European experience and its theoretical rendering in realism and neorealism may be misplaced and/or irrelevant (Holsti, 1992). Most significantly, the theoretical assumption of unit similarity may be inappropriate. If we want to understand the dismaying regularity of war since 1945, perhaps we should look at the domestic structures and politics of states, and not at the external environment. Perhaps Waltz's clear distinction between the principle of hierarchy, which underlies the internal life of states, and the principle of anarchy, which "organizes" international politics, might be amended or reversed. Perhaps the essential characteristic of many post-Communist and Third World states is domestic anarchy, that is, where states as Waltz and Deutsch conceive them do not yet exist, or where they exist more in name than in fact. This is not to deny that in some areas there are genuine security dilemmas, complicated sets of external threats and resulting balancing behavior, construction of deterrents, arms races and even drives for hegemony. One should avoid going from one analytical fallacy-extending realism to the study of conflict in the Third World-to another. Much of the literature on conflict in the Third World has until recently been written from a cold war or geopolitical perspective, and it has generally neglected the domestic sources of conflict in these areas. It would be equally inappropriate to exclude considerations of external threats in the lives of many postCommunist or Third World states, particularly those in the Middle East, the Horn of Africa, and the Balkans. However, it is the case that the origins of conflict since 1945 have derived more frequently from weak statehood, the residues of colonialism, and national fragmentation. Many domestically originating conflicts have become internationalized through complicated networks of ties between dissident groups and external patrons and protectors. The whole process of the internationalization of domestic conflict needs more study (cf. Heraclides, 1990; de Silva and May, 1991). But for the historical foundations of post-1945 war we must turn to the birth of states.

Political Theory and the Composition

of States

European political theory of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries addressed the problem of political authority, obligation, and the state without questioning the bases of the community upon which the state rests. The state of nature in contract

KJ. HOLSTI

325

theory was a metaphor to explain the need for governance (particularly during times of civil disturbance) among atomistic individuals, to outline the benefits it would provide, and to list the costs it would help avoid. The focus is on sources, needs and forms. But one searches in vain in Hobbes or Locke to find exactly who would make the contract among themselves or with a Leviathan. The state of nature is universal, but the states that result from the social contract are particular. They are based on some sort of community, but the authors do not outline its entrance requirements or limits. Hobbes speaks of the commonwealth and Locke of the nation, but these are assumed rather than defined. During their times, the concept of nation carried no ethnic meaning; a nation referred to any "people" who had gained political sovereignty (Gazdag, 1992: 13). Only in Rousseau does community as a social unit begin to appear, this time in the guise of maurs,rendered as customs and habits but not ethnicity. In those philosophers' Europe, the community over which there was governance

was a territorial contrivance created through wars, conquests, marriages, and a few peaceful political amalgamations of previously independent or autonomous units. Community was based on contiguity. In some places, such as France, England, or Sweden, there was an ethnic core (cf. Smith, 1989: 352-353). France, for example, grew originally around areas of the old Frankish kingdom (Paris, the Loire Valley, and the north) but was fashioned later-largely by force of arms and the extension of bureaucratic controls-to incorporate the politically unorganized nations of Bretons, Basques, Alsatians, Occitanians, Catalans, Corsicans, and Flemings as well as a variety of dukedoms and other traditional political units. At the time of the French Revolution, one-half of France's citizens spoke no French, and only about 12 percent spoke it properly. Most of the population in the north and south of the country could not speak the language at all (Hobsbawm, 1990: 60; on the language of the Revolutionary regime, see Maugue, 1979: 46-48). When Italy was unified in the mid-nineteenth century, only about three percent of the population could speak standard Italian; a Sicilian's speech was incomprehensible to a Milanese. Italian

parliamentarian Massimo d'Azeglio's quip, "We have made Italy, now we must

make Italians" expressed well the sequence of state formation in nineteenthcentury Europe: the state came before the nation. Walker Connor (1990), based on research into immigration records prior to World War I, has shown that most European migrants to the United States at the turn of the century had no sense of being Italian, Ukrainian, Croat, or Slovene, much less Yugoslav. Their identities were defined in terms of river valleys, villages, and regions. European sovereigns, reflecting the Eighteenth- and most nineteenth-century

political philosophies of the times, ruled over "civic," "historic," or territorial

communities rather than over "associational" (Buckheit, 1978: 4) or "natural" communities (nations based on consanguinity and/or language and religion). The French "citizen" constructed during the Revolution had nothing to do with some class or ethnic segment of the community. The concepts of patriotism and citizenship were inconsistent with divided loyalties or with special "rights" implied in the modern concept of ethnic minorities or any other special subgroups within the state. Secessionist and unification movements, such as those in the American colonies, based their claims on natural law, not on ethnicity, culture, or some other group attribute. Greek independence in the 1820s was fought for primarily in the name of religious freedom and local political autonomy rather than ethnic identity, while, as suggested, Italian unification had everything to do with liberalism and little to do with the unity of some natural "people." "Nationhood" defined in terms of

326

War,Peace,and the State of the State

its collateral attributes of history, language, and ethnicity-consanguinity-and economic base did not arise in Europe until the late nineteenth century-with Belgium a partial exception. Only then did claims for sovereign statehood in the multi-national Ottoman, Russian, and Austro-Hungarian empires start to be based upon the cultural and language attributes of ethnic communities (cf. Hobsbawm, 1990: 79, 102). Even then, however, some claims (e.g., by the Hungarians) continued to emphasize the restoration of historicrights rather than the unique distinctiveness of language, culture, or ethnicity. The conceptual foundations of state legitimacy changed substantially between the late nineteenth century and the end of World War I. This change was most vividly reflected in the 1919 peace settlement. The state's exclusiveness, once based on history and territory (contiguity) now became based on culture, language, and ethnicity (consanguinity). State territory was made to fit around "natural"community, while WoodrowWilson's ethnically-based understanding of self-determination replaced traditional civic concepts of the state. Even though Wilson did not intend to apply the principle of self-determination to the victorious powers, most analysts expected that once national aspirations in the former multinational empires had been met, a new era of peace would emerge. When Wilson proclaimed that "no people must be forced under a sovereignty under which it does not wish to live" (quoted in Buckheit, 1978: 62), he was stating that all the turmoil of European politics caused by nationalist agitation in the decades prior to the Great War could only be resolved by sovereign statehood for "peoples."Those "peoples"were defined in terms of ethnicity, culture, language, and/or religion. This change in the basis of state legitimacy was also reflected in the victorious Allies' recognition policies. Three criteria were operative in Paris during 1919: the "peoples" must have expressed a desire for sovereign independence; that expression should have been by democratic means, through constitutions, institutions of parliamentary government, or plebiscites; and new "minorities" must have their own rights protected through constitutions, treaties, or League of Nations' guarantees. Wilson's ethnically-based concept of self-determination could not, of course, be applied with precision. Boundaryconfigurations simply could not fit the melange of population distributions. Inis Claude (1955: 13) estimates that even with the "scientific" work of the Paris Peace Conference-the attempt to create states on the basis of "natural" communities-25 to 30 million Europeans remained outside those "natural"communities as they were fashioned into new states. They were to become a source of conflict and war throughout the 1920s, as well as a pretext for Hitler's serial aggressions of the 1930s. The 1919 peace also helped to bring into political vocabulary and policy the concepts of majority and minority. These emphasize differences-us and themrather than the uniformity, similarities, and bonds that are implied in the concept of "patriot"or "citizen." That formal divisions of populations according to ethnic, language, and religious attributes can help foster tensions between them was already recognized in the early twentieth century. Writing in 1907, Lord Acton noted that...

The greatest adversary of the rights of nationality is the modern theory of nationality. By making the State and the nation commensurate with each other in theory, it reduces practically to a subject condition all other nationalities that may be within the boundary.It cannot admit them to an equality with the ruling

KJ. HOLSTI nation which constitutes the State, because the State would then cease to be national, which would be a contradiction of the principle of its existence. According, therefore, to the degree of humanity and civilization in that dominant body which claims all the rights of the community, the inferior races are exterminated, or reduced to servitude, or outlawed, or put in a condition of dependence (Acton, 1907: 192-193).

327

As we will see, this was a prescient observation, but perhaps less relevant in the world of Western Europe with which Acton was familiar than to many of the post1945 states. Europe's states thus came to be based on two fundamentally different foundations of legitimacy: historic-civic (e.g., France, Spain, Sweden, and Denmark) and "natural" (Finland, Hungary, and the Baltic and Balkan states). In the former, the state molded the modern territorial nation, and in the latter the nation (as defined and even created by elites) helped create the state. In 1919, pre-existing "natural" communities simply made a claim for a higher status, that is, for sovereign statehood (Smith, 1986: 240-244). Two hybrid states, based neither on civic nor "natural" foundations, also emerged from World War I: Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. We are now seeing the results. Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia were the creations of diplomats, not the results of long historical processes or of the upgrading of some "natural" community to sovereign statehood. They were fictions that not even seventy years of history or the iron rule of communist regimes could transform into some degree of civic or "natural" community. This is exactly the problem faced by many contemporary post-socialist and Third World states.

State-creation

after 1945

At the first meeting of the new United Nations General Assembly in 1945, 42 governments sent delegates; today, it has more than 180 members. There has been no similar explosion of states in the history of the Westphalian system. If we are to gain an understanding of the etiology of war in the post-Communist and Third arena of armed conflict that is largely ignored in Waltz's and Worlds-that Deutsch's analyses-we should start by looking at the birth of states rather than at the principle of anarchy that underlies the relations between them. and Using the two traditional European criteria of state legitimacy-"civic" "natural"-it is clear most of the post-1945 states met neither at the time they achieved independence. Their claims for statehood were based primarily upon a or anti-Soviet-rather than on the positive achievements of negative-anti-colonial a historical community and its citizenship or on the "natural" bonds formed through history, consanguinity, language, and/or religion. If Europe's post-1918 states were national communities upgraded to states, most post-1945 states remain "nationsto-be." Many derive their legitimacy, "from the circumstances of their origins in deliberate acts of creation-by aliens for alien purposes" (Smith, 1983: 125). The new states were mostly the successors of colonial entities which, as we know, had little to do with historic or "natural" units. The standard depiction of their territorial origins is that of a bureaucrat or diplomat in London, Berlin, Paris, or St. Petersburg drawing straight lines on maps, ignorant of the topographical, natural, or population characteristics of the territories being claimed or bartered. The colonial units usually incorporated all sorts of ethnicities, nations, religions,

328

War,Peace,and the State of the State

languages, and commercial patterns into a single administrative zone, or they tore apart previously integrated societies into separate units (Iraq and Kuwait, for example). The colonial powers also shifted populations indiscriminately, thus creating multi-ethnic societies where they had not existed before. Fiji, Trinidad, Hawaii, and Guyana are prominent examples. The numerous and diverse purposes of colonization-commercial exploitation, slaves, religious proselytization, international status, strategic interests, and great power rivalry-bore no relationship whatsoever to the creation of "states." Indeed, most colonial regimes explicitly sought to avoid building the foundations of statehood. According to Migdal (1988: 141), "British imperial officials ... considered far too extravagant building a colonial state strong enough to either bypass indigenous forces altogether or absorb them into a single system of rules." Imperial officials ruled primarily through the co-option and subsidization of "strongmen" (clan leaders, religious officials, caudillos, and the like), thus leaving the successor political units with highly fragmented systems of social control. Colonial authorities made no attempt to encourage a sense of national consciousness, much less ideas of individual or group rights. Quite the opposite: their task was to exploit resources through forced or cheap labor. This required racist ideologies (except in some cases among French colonialists), and according to Worsley (1964), a process of psychological exploitation or "infantilization," described by Fanon (1961) as colonization of the personality. These hardly constitute solid foundations for modern statehood. The idea that the polyethnic/communal fictions called colonies could someday become independent states emerged only after World War I. By the 1950s it had become the standard wisdom in "national (a misuse of the term) liberation" idealogy and in United Nations rhetoric. Colonial jurisdictions created for multiple nonstate purposes were somehow to become carbon copies or prototypes of the European territorial states that had created them. When leaders of national liberation movements spoke of "self-determination"if they used that term at all-they hardly did so in the name of a "people,"because no such "people"-meaning a "natural" community-existed. There were, rather, congeries of communal-religious groups, ethnicities, tribes, clans, lineages, and pastorals who wandered freely. Lacking "natural"communities or a national history of uniqueness which might legitimate their claims to statehood, they had to rely on the territorial creations and concoctions of the colonialists to define their hopedfor communities. In CrawfordYoung's words (1983: 200): ... anticolonial nationalism foundinconvenient the notionthat culturalaffiniA ties were a necessarybasis for exercising[the right of self-determination]. and alien rule was the essentialcause of revolt. sharedconditionof oppression for ... Thus the particularcolonial territorywas the necessaryframework in of all united Nationalists, seeking support challengingforeign hegemony. of a giventerritory to sanctionthe independence inhabitants demand,embraced to whom selfthe colonialentity itself as the definingbasis for the "people" shouldapply. determination European territorial colonies, many of which had nothing at all to do with "natural" communities or ancient states, were nevertheless to be the basis of the new countries. The problem was that in most cases the country remained a dream rather than becoming a reality. Unlike Europe's centralizing monarchies of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, the gulf between the territorially-based postcolonial state and the plethora of its constituent nations, communities, and ethnic

KJ. HOLSTI

329

groups cannot be easily reconciled in a democratic age. Marriages, armed conquest, and forced integration or assimilation are not policies easily sustained under the eyes of a human rights- and sovereignty-inspired international community. Like Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, many of the post-1945 states began as fictions. It is for this reason, in part, that Robert Jackson (1991) has called these entities "quasi-states" and that Anthony Smith (1986: 244) has claimed even more pessimistically that "the history-less are destiny-less." They owe their creation more to the international community than to their own artificial communities. Many received international recognition before they had met either the traditional criteria of statehood (a defined territory, skills and organizations to administer a permanent population, and capacity to enter into treaty relations), or the 1919 criteria based on "natural"community. They entered the international club, in other words, by virtue of their status as colonies rather than through their achievements as fledgling states.' Thus their essential but very difficult task is to create nationsand in some cases states-where none existed before. These comments do not imply that states or quasi-states came into being only as a result of European imports. In many areas of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, states long pre-dated colonialism, and some of them had geographic delimitations roughly approximating colonial boundaries (cf. Neuberger, 1986: 43). But most post1945 states were congeries of pre-colonial units, and many European administrations partitioned older political structures between two or more colonies. We should not assume that there is some automatic or pre-destined trend to "real" statehood, meaning a close concordance between the government apparatus, civil society, and the "nation." Some former quasi-states-Malaysia, Singapore, Egypt, and the Maghreb countries (except Libya)-have arrived at a semblance of strong statehood. Trinidad and most other Caribbean countries have a pronounced and perhaps untypical record of political strength (Thorndike, 1989). Ukraine has an ancient history and a distinctive language. But other countries have disintegrated or collapsed (Lebanon, Liberia, Somalia, Rwanda). Most post-1945 states are somewhere in between, meaning that their future remains problematic and that many will end up as cases on the United Nations agenda. These comments suggest that some new states have mixed characteristics of anarchy and hierarchy. Waltz (1979: 114-116) considers this possibility but rejects it on theoretical grounds. No matter how much "anarchic"behavior appears within states, they are still organized on hierarchical principles. Any state that is unable to provide for its own defense, that tolerates highly armed political groups within its territory, and that uses excessively predatory or suppressive means to bridge the gap between the state and its nation(s), can hardly be based on hierarchical (mutual dependence) relations. If on a prolonged basis the state cannot provide a minimum level of public security, as is the current case in Somalia, Liberia, or Rwanda, it does not contain the "stuff' of a state despite having flags and an ambassador at the United Nations. The principle of hierarchy, characterized by a division of labor, is the hallmark of the state, according to Waltz. But in Myanmar, for example, how can we speak of a division of labor when the army owns and runs the organized economy, when its members systematically plunder national wealth for private profit, when significant proportions of the population do not accept the legitimacy or the authority of the government (they deny the principle of hierarchy), and when most private commerce and exchange take place outside government purview and supervision? It is difficult to see how such countries are functionally similar to Denmark andJapan, for example. This suggests that we can expect them to be the

330

War,Peace,and the State of the State

locale of armed combat, the arenas of civil and secessionist wars, many of which will become internationalized to some extent. Contrary to the Rousseau-Waltz thesis, then, the security problematic for such states is primarilyinternal, not external (Korany, 1986; Ayoob, 1991; Holsti, 1992). The main rationale for the armed forces of many Third World and post-socialist states is not the fear of external coercion or aggression, but the fear of internal rebellion (cf. Ball, 1988: 393; EkweEkwe, 1990: 154). The poor fit between state and nation-the major legacy of colonialism-is the essential source of wars in the Third World and, more recently, in the residues of collapsed communism. As Herbert Ekwe-Ekwe (1990: 155) has noted, "It is a cruel irony that six million Africans have had to die in the past twenty years [since the early 1970s] in conflicts that center principally on whether or not one African nation or another should belong to states created strategically by European imperialism to exploit the people and their resources." One of the main tasks of the military in Third World countries in fact has been to "integrate"diverse communities into the state's post-colonial territorial domains. From their perspective, they are involved in "nation-building."From the perspective of groups such as the southern Sudanese, Karens, Tamils, Mizo, Nagas, Omoros, and dozens of others, the task of the state's military is to appropriate their lands and resources and to destroy their identity, ways of life, and local forms of governance (Nietschmann, 1987: 7-14; Odhiambo, 1991: 292-298). Ekwe-Ekwe'sstatement above summarizes the fundamental dilemma of many new states. In it is encapsulated the conflict between the principle of a state's territorial integrity and the principle of self-determination (Neuberger, 1986: 106). The attempts to create "nations"where none existed before drive secessionist and irredentist movements, most of which take a violent form under the rubric of the inherent right of self-determination. Without a nation, a state is fundamentallyweak. But in attempting to build strength, usually under the leadership of an ethnic core, minorities become threatened or excluded from power.This is the foundationof the "insecurity dilemma" of most new states. It is the source of most wars in our age. of Weak, Strong, and Failed States In the Third World, as in some of the post-Communist regions, then, the relevant anarchy does not lie primarily in the relations between states, but is a common domestic characteristic. Barry Buzan has made the important distinction between weak and strong states. The distinction-it is actually a dimension-does not lie in military strength, but in socio-political cohesion. Anarchic states possessneithera widelyacceptedand coherentidea of the state nor a governing their powerstrongenoughto imposeunity populations, among The fact that they exist as states at all is in the absenceof politicalconsensus. their them as such,and not disputing largelya resultof otherstates recognizing existence(Buzan,1989:17). Characteristics Further up the ladder of cohesion are those states whose governments rule effectively because they have power, but whose authority relies essentially upon the goodwill of various kinds of "strongmen"who are the de facto rule-makersand value allocators among a variety of ethnic, clan, class, functional, or communal social units (cf. Migdal, 1988:31-39). Then there are states with "mixed"characteristics,followed by strong states whose political life rests on a synthesis or integration of state, society, and nation(s). The critical variable is the degree of a state's legitimacy-which is not

KJ. HOLSTI

331

to be confused with the popularity of a government. Buzan's dimension does not extend far enough, however. The opposite of a strong state is not a weak state, but a failed or collapsed one. Weak States Numerous indicators of strength and weakness are found in different combinations; their interplay remains largely unexplored. Weak states contain various combinations of the following characteristics: 1. The ends or purposes of governance are contested. The clash between fundamentalist and secular Muslim forces reflects such divisions. The lines separating the state from civil society (which itself is poorly articulated and organized) are blurred and contested, further exacerbating regime legitimacy and often resulting in state coercion and predation (cf. Hawthorn, 1991: 31). 2. There are two or more nations or, as Gurr and Scarrit (1989: 375) call them, "differentially treated communal groups" within the state. What is more significant than the profusion of ethnic/communal groups, however, is that one or more are commonly constructed as minorities rather than as equals. The distinction is important. A nation has a common history, ethnic and language ties, and often a territorial and economic base. It does not see itself as a "minority"until it has been so defined in the context of an "outside" state or by some other group. As Nietschmann (1987: 4) points out, the concept of minority is used by the state, not by the nation, and is usually the intellectual basis justifying various forms of exclusion, appropriation,or repression. It is often the state itself that categorizes groups and establishes "differentrules of the game ... for defining groups, legitimizing certain ones and declaring others out of bounds" (Bienen, 1989: 139). Following the conventional state-biased terminology, Gurr and Scarrit (1989: 380) define minorities as "groups within larger politically-organized societies whose members share a distinctive collective identity based on cultural and ascriptive traits recognized by them and by the larger society" (for a somewhat different rendering, see Connor, 1978: 388). The significant quality is the "social perception that [various] traits or combination of traits set the group apart" (Gurr and Scarrit, 1989: 381). Gurr and Scarrit identify 99.countries that have such minorities "at risk."Twenty-eight states in Africa contain 72 groups "at risk." Those groups comprise almost 45 percent of the total population. In Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, the proportion of the population "at risk" is 24.3 percent and in Asia, 18.3 percent. 3. The government apparatus is "captured" or held by one group, which systematically excludes others. If the state is based on the guaranteed structural predominance of a single group, we can all it an "ethnocracy." Its strategies for dealing with "minorities"-and sometimes it is numerical minorities excluding majorities-range from expulsion (Uganda, Myanmar) through forced integration-colonization (Sudan) to various forms of systematic exclusion (Myanmar, Iraq, Sri Lanka) and even to ethnocide (Rwanda). (For a discussion of the strategies, see Rothchild, 1986; for the European experience, see Maugue, 1979: ch. 5, and Coakley, 1992.)

332

War,Peace,and the State of the State

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

The government is "captured"by a family or clan for the primary purpose of personal enrichment (Nicaragua under the Somozas, Haiti under the Duvaliers, the Philippines under Marcos, the Central African Republic under Bokassa, Somalia under Barre, etc.). Following its leaders, the bureaucracy operates primarily through patron-client relations and systematic corruption; governing groups use state capabilities and resources primarily for personal enrichment. Zaire is a contemporary example. This type of regime may be more appropriately entitled a "kleptocracy." Major communal or ideological groups or nations identify with, or are loyal to, external states and/or societies (e.g., the Kashmiris toward Pakistan during the 1950s; the Somalis in Kenya in the 1970s; the Turkish Cypriots; some Shi'ia in Lebanon, etc.); or significant segments of the population owe primary or exclusive loyalty to primordial groups (cf. Jackson, 1987). The state is incapable of delivering basic services or providing security and order for the population (India after partition, Lebanon, Somalia, and Afghanistan today). In these cases, there is indeed a Hobbesian state of nature within the state. The government relies primarily on violence, coercion, and intimidation to maintain itself in power, often targeting nations/minorities or ideological groups (e.g., Iraq under Hussein, Myanmar) in order to gain support from other groups. Most fundamentally, the state lacks legitimacy. Its inhabitants "... do not readily regard their rulers as providing a legitimate authority, and state power does not rest on a secure foundation of popular belief in the right of rulers to rule" (O'Brien, 1991: 145).

In Michael Mann's (1986: 109-136; cf. Thomas, 1989) terms, the weak state is high in despotic power, but low in infrastructural power. It can rule through coercion, but it has no deep roots within civil society. This list is suggestive, not exhaustive. Other characteristics are also relevant (cf. Korany, 1986: 553-556). However, it contains important elements, and can also serve as a basis of comparison with the slow and often violent process of state-formation in early modern Europe. Strong States Strong states contain characteristics opposite of those found in weak states, as well as others. 1. The ends and purposes of government have become settled, founded on a significant ideological consensus. Politics are thus "de-passioned" (Brenner, 1992). They revolve primarily around technical issues and priorities rather than purposes and creeds. In most modern industrial societies, for example, there is a consensus that the purpose of governance is to help provide "the good life" for the individual through the means of the welfare state. The division between the state and civil society is established-and mostly honored-through constitutional guarantees and less formal "rules of the game." Broadly speaking, ruling authorities and/or state institutions enjoy a high level of legitimacy if not always popularity.

KJ. HOLSTI

333

Most social groups-ethnic, religious, language, and the like-have been successfully assimilated, or have achieved protection, equality, or selfdetermination through autonomy, federalism, or other special devices. Sovereign statehood through secession no longer constitutes a major goal of constituent nations/minorities. Ideological, religious, and other groups operate freely and participate in the political process. 3. Territorial frontiers have become legitimized and sanctified through numerous treaties and in multilateral instruments. The spatial dimension of state jurisdiction is not contested domestically or externally, and norms against forceful revision (e.g., the Helsinki Final Act) hold. 4. Governors change through regularized procedures. It is impossible for one group or social sector to hold power permanently, and no group faces systematic persecution or denial of civil liberties and political office. 5. Major state organizations such as the military remain under effective civilian control. 6. The mores of governance preclude personal enrichment through political activity. In Michael Mann's terms (1986: 109-136), the modern industrial state is low on despotic power, but high on infrastructural power. The roots of the state lie deeply within (and sometimes intrude upon) the civil society. Pomian (1991), in a parallel analysis, has suggested categories of horizontal and vertical integration to measure the strength of statehood. A state is horizontally integrated when its territorial base is essentially uncontested; borders are recognized and considered legitimate both within and outside the country. Vertical integration implies that a state is able to handle social conflicts and to allocate values without having to resort to violence; no social group is systematically excluded from governance. 2. Failed States States fail or collapse when one or more of the following characteristics prevail: 1. There are one or more armed "mini-sovereigns" within the state. They have effective rule-making capacity and are armed sufficiently to resist central authorities. The clan chiefs of Somalia and the PLO in Lebanon prior to the Israeli invasion of 1982 are examples. 2. An external power wields effective authority or influence within the territory of the state and has the coercive capacity to resist pressures from the legal authorities. Syria in Lebanon and the Soviet Union in Afghanistan are examples. 3. Communities war against each other and the central authorities do not have the capacity to end the slaughter. Rwanda in 1994 is an example. 4. A state is incapable of providing minimal security for the ordinary tasks of life-commerce, transportation, agriculture, and communication-to proceed. These tasks must be performed by outsiders, as has been done by the United Nations in Somalia, or by local warlords. It is important to emphasize that these characteristics constitute ideal types of "weak," "strong," and "failed" states. Most states, most of the time, can be placed in various positions on a continuum, the ends of which are the ideal types. States

334

War,Peace,and the State of the State

over time also move along the continuum toward greater strength or weakness. Few West European states completely approximate the "strong"state-the position of "gastarbeiter"and refugees in Germany, some Quebecois in Canada, and Basques in Spain suggest significant deviations. There are equally few pure "kleptocracies" or "ethnocracies."The main point is that those states that are located toward the "strong"part of the continuum are sites of peace, while those tending toward the "weak"or "failed" parts are sites of war. The Characterof States and War Strong states are a necessary condition for peace. Today, a fundamental source of international conflict is anarchy within states. Peace in Western Europe or North America since 1945 cannot be explained, as have most realists (cf. Waltz, 1979; Gaddis, 1987; Mearsheimer, 1990), solely by the cold war, nuclear weapons, American hegemony, or balances of power. Western Europe is also more than a society of states (Bull, 1977) or a "mature anarchy" (Buzan, 1983: 96-101). Peace between the Western industrial countries, I suggest, comes primarily from the fact that there has been peace within each of its constituent units. Anarchy, although being altered through the European Union, has remained the organizing principle for the mutual relations of the North American and Europeanstates. Yet, in contrast to a Rousseauistic or Waltzian prediction, war has not recurred (cf. Deutsch, 1957). Europe, North America, and to a lesser extent South America are anomalies, but very significant ones. If the principle of anarchy-a constant property between states-has not changed, and if systemic characteristics such as balances of power are not to be found in many regions of the world, then the explanation of the significant variation in war incidence must lie in characteristics within states. It follows that regions populated by large numbers of weak and/or failing states will be zones of war, areas of high incidence of both internal and interstate armed conflicts, while regions containing large numbers of states of medium strength will be no-war zones. There may be frequent militarized crises, arms competition, and ad hoc alliance-making, but the incidence of internal wars will be relatively low, and the incidence of interstate wars negligible. South America since the early twentieth century fits this profile. Finally, regions containing a predominance of strong states will be "pluralistic security communities," where both internal and interstate wars will be almost unthinkable. Western Europe since 1945, North America since the 1920s, and the South Pacific region concentrated on Australia and New Zealand, fit this pattern (cf. Buzan, 1989: 23; Kacowicz, 1994). A competing theory, the theory of the "democratic peace," has gained many adherents and empirical support since first enunciated by Montesquieu and Kant. Many of the characteristics listed in the "strong" state category duplicate democratic political structures and procedures, but the category also highlights relations between groups within the state, state-group relations, the legitimacy of established boundaries, and a consensus on the ends of governance. It takes more than periodic elections, multiple parties, and civil liberties to make a strong state. Democratic institutions are just part of the story, albeit an important part. The democracy-peace theory is not sufficient, however, because as the South American anomaly suggests, there have been zones of international peace where there has been little or no democracy (Holsti, forthcoming). In the case of the Third and post-Communist worlds, the absence of alliances, balances of power, and other indicators of a classic anarchic system (the Middle

KJ. HOLSTI

335

East is a significant exception), combined with the recurrence of war, also suggests that the fundamental sources of armed conflict lie within rather than between states. Despite flags, UN membership, and other symbols of sovereignty, many Third World and post-Communist states are significantly-and perhaps functionallydifferent from those in Western Europe, North America, and most of South America. Many governments, for example, do not have the purpose of providing "the good life" for their citizens. Their primary purpose is to provide the good life for one segment of the society, whether a clan, an ethnic or religious group, a family, or an organization such as the army . Waltz's concepts of anarchy and hierarchy are ideal types, and for reasons of theoretical parsimony, simplifying assumptions have to be made. But if my argument carries weight, then we really have two worlds of world politics, one populated by strong states, the other by weak and failed states. The characteristics of relations among the former differ significantly from those of the latter. This can be shown empirically using many different indices. If all states were the same, as Waltz suggests, then we should not observe such significant differences in the outcomes of relationships. There should be wars, balances of power, hegemons, and arms races just as much in Europe, North America, and South America as anywhere else in the world. Yet this is not the case. In the Third and post-Communist worlds, we find the recurrence of war, but balances of power and hegemony-seeking except in the Middle East are rare. In summary, if we wish to look for the sources of war in these areas, we should jettison many of our traditional analytical devices whose origins lie in European history (Korany, 1986; Holsti, 1992). The study of the state, ethnicity, and comparative politics provides a better theoretical and methodological platform. Policy Implications If the analysis has some plausibility, then our conceptions of international organizations and of the constitutive principles of international practice need re-examination. It is important to recall that the fundamental principles underlying organizations such as the United Nations are Westphalian. The principles of sovereign equality, of non-interference, and of territorial integrity which are the foundations of most contemporary international organizations are important protective devices for the small and weak against external predators. Imagine how many countries would have shared the fate of Kuwait in July 1990 were not the principles of sovereignty and independence among the most sacred of the society of states. This is one reason why in the last three centuries we have witnessed the birth of so many states, and the demise of so few. The sanctity and mystique of statehood remain strong. Yet, since most of the threats to weak states are internal rather than external, how can international organizations act when their chief mandate is to maintain international peace and security? The Somalian situation brings this question to the

forefront. Should the UN attempt to take over the functional tasks of a state when the indigenous rulers cannot perform them? Should its purpose be to resuscitate quasi-states that have fallen into chaos and warlordism? Or should the international community develop new forms of trusteeship, giving itself the very long range and costly task of creating a genuine civic society in a milieu where it is lacking? Can the international community create strong states? What sorts of norms should guide the efforts of international organizations in their peace-keeping and peace-making tasks? Should the purpose, other than

336

War,Peace,and the State of the State

stopping the killing, be to reconstitute states that are largely fictional or to promote the Wilsonian idea of "natural" self-determination? These are not abstract questions. Where peace-keeping missions have been unable to help bring ethnic reconciliation-as is the case of Cyprus-should they continue to drain the coffers of the United Nations and contributing governments in the expectation that another twenty or thirty years of non-warfare may lead to an eventual restoration of the prewar situation? Or should the international community recognize that perhaps the most viable principle of legitimacy is statehood based on some "natural"community? If so, would it not make more sense, for example, to accept the fact of a Turkish Cypriot state? The peace being worked out for Bosnia, as much as it may be a cause for future strife, implicitly takes the anti-Deutsch position that it is better to separate peoples than to try to integrate them. But this challenges the liberal faith (and pre-twentieth-century practice in most multi-national empires) that a society can incorporate many groups on the basis of equality and The problem with the ethnic "solution," of course, is that it can be taken to absurd lengths. If, as Gurr and Scarrit suggest, the world has more than 250 minorities/nations at some degree of risk, then we could well expect claims from most of them for sovereign statehood. We would then have, let us say, another 200 states added to the present 185. Most of them would have authoritarian rule (Etzioni, 1992) and be non-viable economic entities, but at least for the time being the passion for "identity," "international recognition," and a "place in the sun" would be satisfied. The economic fragility of many of these "states"would ultimately force them to find new modes of political integration. It is unlikely, however, that governments in most Third World countries will sympathize with the Wilsonian conception of state legitimacy, for to do so would invite an increased incidence of secessionist pressures and greater external scrutiny of their domestic politics. If United Nations-sponsored peace arrangements, as in Bosnia, sanction all sorts of partitions and new states, all based on the doctrine of consanguine self-determination, very few governments in the Third World would be immune from the claims of their own constituent groups to upgrade their status to sovereign statehood. Many Third World and post-Communist countries live a precarious existence in their post-colonial guise. There is a competition-often lethal-between the forces of "state-building" and the forces of fragmentation and autonomy, those nations and groups that have their own histories, identities, strategies for survival, and localized systems of rule-making. They often take up arms for their "rights,"or for self-protection against predators, including their own governments (cf. Gurr, 1993). Governments, on the other hand, have their own agendas of "national integration," "nation-building,"and eradication of "communists"and "terrorists,"or anyone else who gets in the way. Civil wars are the result; a significant proportion of them become internationalized and foreign intrusion usually prolongs the contest of arms. Until today, the international community has shown only mild sympathy for the forces of secession. Third World states, in particular,jealously guard their concept of sovereignty and (colonial) territorial integrity. Their interpretation of the right of self-determination adheres strictly to a non-Wilsonian conception of the bases of state legitimacy. It is a concept that must be applied to a territory-the colonyand not to particular groups within it. Self-determination was achieved, according to the Organization of African Unity, in the act of "national liberation" against colonialism, and that act is to apply for all time. It is irreversible and non-amendcivility.

KJ. HOLSTI

337

able. There can be no such thing as "self-determination" for the Kashmiris, Punjabis, Sikhs, Karens, Chins, Tamils, Ibos, Baganda, and all the rest. United Nations Resolution 1514, the "Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples," clearly states the prevailing doctrine: " ... any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national [sic] unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations." It is in part because of this interpretation of state legitimacy that, despite the myriad of secessionist movements since 1945 (but excluding the collapse of the Soviet Union) there have been only four peaceful secessions (Anguilla, Singapore, Mayotte, and Slovakia) and four successful violent secessions (Pakistan, Eritrea, Slovenia, and Croatia). It is thus one of the ironies of twentieth-century history that Wilson's concept of self-determination, which was supposed to be a pathway to peace, has become a major justification for war and has resulted in national and international "pandaemonium" (Moynihan, 1993). The tenets of realism and geopolitical analysis have blinded us to the continuing search for politically effective communities. This has been a major source of international instability for more than a century. In some areas the search has led to peace, but the record of war since 1945 indicates that the European territorial state has not been a successful prototype for many non-Western communities. The war between nations and the state continues unabated in many parts of the world, and presents numerous intellectual and moral challenges for both academics and the institutions of the international community. Note

1. This characterization is representative of many Third World and former Soviet republics. They had no pre-colonial pedigree of statehood. Significant exceptions include India, the Maghreb countries (except Libya), Egypt, Ethiopia, Burundi, Rwanda,Madagascar,Lesotho, Botswana, the Baltic states, and Ukraine. Some small island colonies also had forms of statehood prior to Western colonization. In the remainder, there were various forms of statehood, but they did not approximate colonial or contemporarystate boundaries.

References

and Other Acton, Lord J.E. (1907). "Nationality." In TheHistoiy of Freedom Essays, (.N. Figgis, ed.). London: Macmillan. since 1945. London: Cassells. Arnold, G. (1991). Warsin the Third World "The Problematic of the Third World." WorldPolitics, 43 (1): M. (1991). Security Ayoob, 257-283. in the ThirdWorld.Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ball, N. (1988). SecurityandEconomy and Changein Africa. Boulder: Westview Press. Forces,Conflicts Bienen, H.S. (1989). Armed Brenner, M. (1992). "Discord and Collaboration: Europe's Security Future." Paper delivered at the symposium, "Discord and Collaboration in a New Europe," Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA, October 29-31. New Haven:Yale UniversityPress. theLegitimacy Buckheit,L.C. (1978). Secession: ofSelf-Determination. Bull, H. (1977). TheAnarchicalSociety.London: Macmillan. in International Relations. Problem Buzan, B. (1983). People,States, andFear: TheNational Security Brighton: Harvester Press. Buzan, B. (1989). "The Concept of National Security for Developing Countries." In Leadership and National Security, (M. Ayoob and C.A. Samudavanija, eds.), pp. 1-28. Perceptions Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

338

War,Peace,and the State of the State

Claude, I. (1955). NationalMinorities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Coakley, J. (1992). "The Resolution of Ethnic Conflicts: Towards a Typology."International PoliticalScience Review. 13(4): 343-358. Connor, W. (1978). "A Nation is a Nation, is a State, is an Ethnic Group is a ... "Ethnic andRacial Studies, 1(4): 441-472. Connor, W. (1990). "When is a Nation?"EthnicandRacial Studies. 13(1): 92-103. de Silva, K.M. and RJ. May, (eds.) (1991). Internationalization London:Pinter. ofEthnicConflict. and the NorthAtlanticArea. Princeton: Princeton Deutsch, K.W. (1957). Political Community University Press. in Africa: Nigeria, Angola, Zaire. London: Ekwe-Ekwe, H. (1990). Conflict and Intervention Macmillan. Etzioni, A. (1992). "The Evils of Self-Determination." ForeignPolicy, (Winter): 20-36. de la terre. Paris: Maspero. Fanon, F. (1961). Les damnes into the Historyof the Cold War.Oxford: Oxford Gaddis, J.L. (1987). The Long Peace:Inquiries University Press. Gazdag, F. (1992). "Nation, Regionalism and Integration in Central and Eastern Europe." Paper #4. Athens: Panteion University, Institute of International Relations Occasional Research. Gurr, T.R. (1993). "WhyMinorities Rebel: A Global Analysis of Communal Mobilization and Conflict since 1945."International Political Science Review, 14(2): 161-202. Gurr, T.R. and J.R. Scarrit (1989). "MinorityRights at Risk: A Global Survey."HumanRights 11: 375-405. Quarterly, Hawthorn, G. (1991). "'Waiting for a Text?': Comparing Third World Politics." In Rethinking ThirdWorld Politics, (J. Manor, ed.). London: Longman. Heraclides, A. (1990). "Secessionist Minorities and External Involvement." International 44(3): 340-378. Organization, Herbst, J. (1989). "The Creation and Maintenance of National Boundaries in Africa." International 43(3): 673-692. Organization, since1780. Cambridge: Cambridge University Hobsbawm, EJ. (1990). NationsandNationalism Press. Armed andInternational 1645-1989. Cambridge: Holsti, KJ. (1991). Peaceand War: Order, Conflicts Cambridge University Press. Holsti, KJ. (1992). "International Theory and War in the Third World." In The Insecurity Dilemma: NationalSecurity in the ThirdWorld,(B.Job, ed.). Boulder: Lynne Rienner. Holsti, KJ. (forthcoming). War, the State, and the State of War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jackson, R.H. (1987). "Quasi-states, Dual Regimes, and Neoclassical Theory: International Jurisprudence and the Third World."International Organization, 41(4): 519-549. International Jackson, R.H. (1991). Quasi-states: Relations, and the Third World. Sovereignty, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Jackson, R.H. and C.G. Rosberg (1982). "Africa'sWeak States Persist: The Empirical and the Juridical in Statehood." World Politics, 35(3): 1-24. Kacowicz, A. (1994). "Explaining Zones of Peace: Democracies as Satisfied Powers?"Paper presented at the XVIth World Congress of the International Political Science Association, Berlin, August 21-25. Korany, B. (1986). "Strategic Studies and the Third World: A Critical Evaluation." International Social ScienceJournal, 38(4): 547-562. Mann, M. (1986). "The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms, and Results." In Statesin History, J.A. Hall, ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. I'Etat-Nation.Paris: Editions Danoel. Maugue, P. (1979). Contre R.D. (1989). Third World Determinants andImplications. London:Pinter. Military McKinlay, Expenditure: Mearsheimer, J. (1990). "Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War." International Security,15(2): 5-56. Relations and State Capabilities Migdal,J.S. (1988). StrongStatesand WeakSocieties: State-Society in the ThirdWorld. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

KJ. HOLSTI

339

Ethnicity in InternationalPolitics. London: Oxford Moynihan, D. (1993). Pandaemonium: University Press. Nietschmann, B. (1987). "The Third World War." CulturalSurvivalQuarterly, 11(3): 1-16. in Postcolonial Africa. Boulder: Lynn Rienner. Neuberger, B. (1986). National Self-Determination O'Brien, C.B. (1991). "The Show of State in a Neo-Colonial Twilight: Francophone Africa." In RethinkingThird World Politics, (J. Manor, ed.). London: Longman. Odhiambo, A. (1991). "The Economics of Conflict Among Marginalized Peoples of Eastern Africa." In ConflictResolutionin Africa, (F.M. Deng and I.W. Zartman, eds.). Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. Pomian, K. (1991). "Les particularites historiques de L'Europe centrale et orientale." Le Debat,janvier. Rothchild, D. (1986). "Interethnic Conflict and Policy Analysis in Africa." Ethnic and Racial Studies, 9(1): 66-86. Selcher, W.A. (1990). "Brazil and the Southern Cone Subsystem." In South Americain the 1990s: EvolvingInternational in a New Era, (P. Atkins, ed.). Boulder: Westview Relationships Press. toArms: International and Civil Wars,1816-1980. Beverly Small, M. andJ.D. Singer (1982). Resort Hills: Sage Publications. The Western State andAfricanNationalism. Smith, A.D. (1983). State andNation in the ThirdWorld: Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books. Smith, A.D. (1986). "State-Making and Nation-Building." In States in History,(.A. Hall, ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Smith, A.D. (1989). "The Origins of Nations." Ethnic and Racial Studies, 12(3): 341-367. Thomas, C. (1989). "Conclusion: Southern Instability, Security and Western Concepts-On an Unhappy Marriage and the Need for a Divorce." In The State andInstabilityin the South, (C. Thomas and P. Saravanamuttu, eds.). New York: St. Martin's Press. Thorndike, T. (1989). "Representational Democracy in the South: The Case of the Commonwealth Caribbean." In The State and Instabilityin the South, (C. Thomas and P. Saravanamuttu, eds.). New York: St. Martin's Press. Politics. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley. Waltz, K.N. (1979). Theory of International Worsley, P. (1964). The Third World.London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. Young, C. (1983). "Comparative Claims to Political Sovereignty: Biafra, Katanga, Eritrea." In State Versus Ethnic Claims: AfricanPolicyDilemmas,(D. Rothchild and V. Olorunsola, eds.). Boulder: Westview Press.

Biographical Note KJ. HOLSTI, of the University of British Columbia, has published extensively in the field of international relations. His most recent books are Peace and War: Armed Conflicts and International Order, 1648-1989 (Cambridge University Press, 1991) and War, the State, and the State of War (forthcoming, 1996). He is a past editor of the International Studies Quarterly, and has served as president of both the Canadian Political Science Association and the International Studies Association. ADDRESS: Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada V6T 1Z1.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The Concept of SecurityDokumen15 halamanThe Concept of SecurityFaisal SulimanBelum ada peringkat

- Osorio PDFDokumen30 halamanOsorio PDFBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- 2009 Deibert Geopolitics CyberspaceDokumen0 halaman2009 Deibert Geopolitics CyberspaceBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- States, Security Complexes, and Concepts Defined in Political TheoryDokumen2 halamanStates, Security Complexes, and Concepts Defined in Political TheoryBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Swami Rama - Path of Fire and Light, Vol. 1 - Advanced Practices of Yoga (1996, Himalayan Institute Press) PDFDokumen88 halamanSwami Rama - Path of Fire and Light, Vol. 1 - Advanced Practices of Yoga (1996, Himalayan Institute Press) PDFBarnabe Barbosa100% (8)

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDokumen13 halamanProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- j.1475-5661.2010.00381.x (1) War GregoryDokumen33 halamanj.1475-5661.2010.00381.x (1) War GregoryBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Geography, Rebel Capability, and The Duration of Civil ConflictDokumen26 halamanGeography, Rebel Capability, and The Duration of Civil ConflictBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Progress in International Relations Theory - Appraising The Field - Colin Elman and Miriam Fendius ElmanDokumen521 halamanProgress in International Relations Theory - Appraising The Field - Colin Elman and Miriam Fendius ElmanKhush Hal S Lagdhiyan100% (1)

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDokumen13 halamanProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Índice de Paz Mundial 2013Dokumen106 halamanÍndice de Paz Mundial 2013Christian Tinoco SánchezBelum ada peringkat

- SIPRI Yearbook 2013 SummaryDokumen28 halamanSIPRI Yearbook 2013 SummaryStockholm International Peace Research InstituteBelum ada peringkat

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDokumen13 halamanProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Constructivism International RelationsDokumen311 halamanConstructivism International RelationsAngga P Ramadhan100% (9)

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDokumen13 halamanProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Progress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseDokumen13 halamanProgress in Human Geography: Mapping Knowledge Controversies: Science, Democracy and The Redistribution of ExpertiseBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

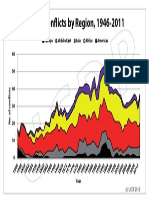

- Armed Conflicts by Region, 1946-2011: 60 Europe Middle East Asia Africa AmericasDokumen1 halamanArmed Conflicts by Region, 1946-2011: 60 Europe Middle East Asia Africa AmericasBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Creveld - Transformation of WarDokumen34 halamanCreveld - Transformation of WarBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- World Bank. The Cost of ViolenceDokumen111 halamanWorld Bank. The Cost of ViolenceBarnabe BarbosaBelum ada peringkat

- Zoontologies. The Question of The Animals PDFDokumen226 halamanZoontologies. The Question of The Animals PDFMateus Uchôa100% (2)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)