12 Budgeting-Intrinsic-2010 PDF

Diunggah oleh

RizKy RamadhanJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

12 Budgeting-Intrinsic-2010 PDF

Diunggah oleh

RizKy RamadhanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH IN ACCOUNTING Vol. 22, No. 2 2010 pp.

133153

American Accounting Association DOI: 10.2308/bria.2010.22.2.133

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation in Budgeting: Antecedents and Consequences

Bernard Wong-On-Wing Southwestern University of Finance and Economics and Washington State University Lan Guo Wilfrid Laurier University Gladie Lui Lingnan University

ABSTRACT: Based on Self-Determination Theory SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005, the present research proposes and tests a motivation-based model of participation in budgeting that distinguishes among intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, and controlled extrinsic motivation for participative budgeting. The proposed model was tested using a survey conducted among managers of an international bank. The results suggest that while intrinsic motivation and autonomous extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting are positively related to performance, controlled extrinsic motivation is negatively associated with performance. These ndings highlight the importance of distinguishing among various forms of motivation in participative budgeting research and suggest that the mechanism by which the information benets of participation in budgeting are obtained may be more complex than assumed. The results also provide evidence of the viability of using the proposed model to study commonly assumed reasons for participative budgeting within a general theoretically based framework of motivation. Keywords: Self-Determination Theory; participative budgeting; intrinsic motivation; autonomous extrinsic motivation; controlled extrinsic motivation; performance. Data Availability: Please contact the rst author.

We thank Theresa Libby editor, two anonymous reviewers, and Steve Kaplan for their helpful comments and suggestions. The rst author is a visiting scholar at Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

Published Online: September 2010 133

134

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

INTRODUCTION ollowing the work of motivation theorists e.g., Lepper et al. 1973; Deci 1975; Lepper and Greene 1978; Deci and Ryan 1985, the present research proposes and tests a motivationbased model of participation in budgeting PB. The current study distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for PB. Individuals are intrinsically motivated if they view PB as an end in itself. For example, they may derive a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction from the mere act of participating. On the other hand, they are extrinsically motivated if they participate as a means to achieve some separable objective. Based on Self-Determination Theory SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005, the present study further distinguishes between autonomous and controlled forms of extrinsic motivation. In the present context, individuals would be motivated by autonomous extrinsic motivation if they truly identied with the value of PB, whereas they would be motivated by controlled extrinsic motivation if they participated because they were pressured by an external force e.g., superiors demand or an internal force e.g., their own sense of anxiety. Research Vallerand 1997; Gagn and Deci 2005 shows that unlike intrinsic motivation and autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation, controlled forms of extrinsic motivation can produce negative consequences. The present research is motivated by several factors. First, considering the extant motivation research literature see, for example, Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005, a review of prior studies in PB see, for example, Covaleski et al. 2003; Shields and Shields 1998 highlights the inadequate use of the term motivation. In particular, research in PB does not differentiate among different types of motivation. Distinguishing among various types of motivation is important since they have been shown to lead to different consequences for a review, see Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005. The present study seeks to provide preliminary evidence of the signicance of differentiating among intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, and controlled extrinsic motivation in PB research. Second, in an analysis of published PB research Shields and Shields 1998, 57 note that most studies do not explicitly state their assumed reasons for PB. They argue that, a desirable, if not necessary, condition for research on participative budgeting to make more systematic progress in developing a general theory is to focus on understanding why it exists. Extant research e.g., Vallerand 1997; Ryan and Deci 2000a; Gagn and Deci 2005 asserts that individuals stated reasons for a behavior indicate the underlying motivation for that behavior. Consistent with that argument, the present research proposes that the stated reasons for PB reect various underlying forms of motivation for PB. This enables the reasons for PB to be studied within a general theoretically based motivation framework. For example, the commonly assumed reasons related to individuals sense of personal satisfaction, feeling of accomplishment, and feeling of belonging and identication, as well as reasons related to goal setting and information sharing, all indicate the underlying motivation for PB. Third, research in PB has generally been studied from the perspective of the rm and that of the individual employee Covaleski et al. 2003. Whether individuals perspectives coincide with that of the rm is important. Consider, for example, the information sharing purpose of PB. On one hand, from the rms perspective, information sharing is a main reason for PB Shields and Shields 1998 and a major mechanism by which the benets of PB are achieved Covaleski et al. 2003. In particular, according to economic models of PB, management induces the subordinate to reveal private information in order to allocate resources more efciently Baiman and Evans 1983; Penno 1984. On the other hand, from the individual subordinates perspective, research in motivation e.g., Vallerand 1997; Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005 predicts that inducing employees to share information may lead to the controlled form of extrinsic motivation for PB, which may have possible negative consequences. To the extent that the two perspectives do not match, the intended benets of PB are less likely to be obtained. The present study provides

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

135

preliminary insights into the extent to which individuals perspective relating to the commonly assumed information sharing reason corresponds with that of the rm. In summary, the present research examines PB from the perspective of the individual participant. It integrates the commonly assumed reasons for PB within a single framework based on motivation theory. Specically, it studies those reasons for PB in terms of intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, and controlled extrinsic motivation. The current research also examines antecedents and the consequence of different forms of motivation for PB. Based on the motivation and the PB research literature, individual variables e.g., organization commitment and situational variables e.g., environment dynamism are postulated as antecedents of individuals different types of motivation for PB. The different types of motivation are in turn predicted to inuence important consequences e.g., individuals performance. The proposed model was tested using a survey conducted among managers of an international bank. The results suggest that individuals can be both intrinsically motivated and extrinsically motivated to participate in the budgeting process. Specically, both intrinsic motivation and autonomous extrinsic motivation are positively correlated with PB. Moreover, while intrinsic motivation and autonomous extrinsic motivation are positively associated with performance, controlled extrinsic motivation is negatively associated with performance. As for the antecedents, organizational commitment is positively associated with all forms of motivation and PB. Environmental dynamism, on the other hand, is negatively related to autonomous extrinsic motivation and PB. The present study has implications for both research and practice. First, the proposed model enables the study and integration of research on the reasons for PB within a theoretically based framework of motivation. Second, the nding of a differential effect of intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, and controlled extrinsic motivation on performance suggests the need for further examining the various forms of motivation for PB. Third, from a practice standpoint, the ndings of the present study, which focused on individual participants motivations, indicate that their view of PB may differ from that intended by top management. In particular, this suggests that the mechanism by which the information benets of PB are obtained may be more complex than assumed. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The following section presents the theoretical background of the study. Next, a motivation-based model of PB is proposed and hypotheses are developed. The research method is then described, followed by the results and their discussion and implications. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation Motivation theorists Lepper et al. 1973; Deci 1975; Lepper and Greene 1978; Deci and Ryan 1985 distinguish intrinsic from extrinsic motivation. In general, a person is described as intrinsically motivated if he or she performs an activity for its own sake, and derives pleasure and satisfaction from participating in the activity. In contrast, an individual who is extrinsically motivated performs an activity as a means to an end. He or she does not engage in the activity for the inherent pleasure that may be experienced while performing it, but instead in order to receive something positive or to avoid something negative once the activity is completed Deci 1975. More recently, self-determination theory SDT; Ryan and Deci 2000b, 2002 has further differentiated among different forms of extrinsic motivation that vary in their relative autonomy or self-determination. Extrinsic motivation is of an autonomous type when behavior is performed out of choice because individuals value the behavior. In contrast, extrinsic motivation is of a controlled i.e., nonautonomous type when ones behavior allows for satisfaction of an external

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

136

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

demand or reward contingency, or to avoid guilt or anxiety Ryan and Deci 2000b, 72.1 The distinction among the various types of motivation is important since research see, for example, Vallerand 1997 in general provides evidence of positive outcomes for intrinsic and the autonomous form of extrinsic motivation, and negative outcomes associated with the controlled form of extrinsic motivation. More specically, Gagn and Deci 2005, 346347 note that with respect to performance, intrinsic motivation and autonomous extrinsic motivation are superior to controlled extrinsic motivation, especially on relatively complex tasks such as PB. Reasons for Participation in Budgeting Psychology-based PB research e.g., Ronen and Livingstone 1975; Hopwood 1976; Brownell and McInnes 1986 generally considers three mechanisms by which the benets of participation are achieved. These are value attainment, the motivational and the cognitive mechanisms. According to Locke and Schweiger 1979, if employees are able to attain their values by participating, increased morale and job satisfaction will result. Values are broadly dened as what employees want. They can be tangible e.g., money or intangible e.g., self-expression. From the motivational mechanism perspective, participation may lead to employees increased trust and sense of control, more ego involvement, increased identication with the organization, the setting of higher goals, and increased goal acceptance. These factors presumably result in increased performance through less resistance to change and more acceptance of, and commitment to, specied goals Locke and Schweiger 1979. From the cognitive mechanism perspective, participation is seen as a conduit for information exchange, and it provides for better upward communication and understanding of the job and the decision-making process. These factors are believed to lead to improved performance by increasing the ow of information Locke and Schweiger 1979. The foregoing discussion highlights three important points. First, the term motivation, as is employed in the participative budgeting literature, is inadequate since it does not differentiate among the different types of motivation. Second, it is unclear whether the information reasons as described in the participative budgeting literature reect autonomous or controlled types of extrinsic motivation. According to SDT, information reasons would reect controlled extrinsic motivation if PB is used by management to induce subordinates to reveal information that they otherwise would not see Covaleski et al. 2003. Third, the value attainment mechanism may reect different forms of motivation depending on the specic value e.g., money versus selfexpression sought by the individual. In light of the preceding three observations, the following section proposes a motivation-based framework for studying the commonly assumed reasons for PB. A MOTIVATION-BASED MODEL OF PARTICIPATION IN BUDGETING Extant research e.g., Vallerand 1997; Ryan and Deci 2000a; Gagn and Deci 2005 argues that the stated reasons for a behavior e.g., PB indicate individuals motivation for that behavior. Consistent with that notion, the present research attempts to integrate the foregoing reasons for PB within a general motivation-based framework see Figure 1. Several features of the proposed

1

According to SDT Ryan and Deci 2000b, autonomous extrinsic motivation consists of identied and integrated regulation. With identied regulation, behavior is performed out of choice because individuals value the behavior. In integrated regulation, individuals not only internalize the reasons for their behavior, but they also assimilate them to the self. In contrast, external and introjected regulations are controlled types of extrinsic motivation. In the case of external regulation, behavior is performed primarily to satisfy an external demand or to obtain an externally imposed reward contingency. In introjected regulation, individuals partly internalize the reasons for their actions although they have not accepted the regulation as their own. One is motivated by introjected regulation when one performs certain tasks to avoid a sense of guilt or anxiety, or to enhance ones ego.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

137

FIGURE 1 Theoretical Model

H1d Individual Variable: Organizational Commitment H1c Autonomous Extrinsic Motivation H2b Performance H2c H2d Controlled Extrinsic Motivation H3c H4c H3b H4d H4b Situational Variable: Environmental Dynamism H1a H4a H1b Participation in Budgeting Intrinsic Motivation

H3a

H2a

model are noteworthy. First, central to the model is the distinction among intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, and controlled extrinsic motivation for PB. On one hand, individuals may be intrinsically motivated to participate because they view their participation as an end in itself. For example, their participation gives them a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. On the other hand, individuals may be extrinsically motivated to participate because they view their participation as a means to an end. This extrinsic motivation may be of the autonomous form if, for instance, PB is viewed as a means for the participant him/herself to set higher goals or goals on which he/she will be evaluated. In contrast, the extrinsic motivation may be of the controlled type if, for example, PB is perceived to be a means for management to obtain information from the participant. Second, the proposed model enables the integration and study of the reasons for participation described in the research literature Shields and Shields 1998; Locke and Schweiger 1979 within a theoretically based motivation framework. The present research specically examines the commonly assumed reasons related to individuals sense of personal satisfaction, feeling of accomplishment, and feeling of belonging and identication, as well as reasons related to goal setting and information sharing. Following research in motivation, these reasons are presumed to indicate the form of motivation for PB. Third, the model incorporates both antecedents and consequences of different types of motivation for PB. Consistent with the PB literature Shields and Shields 1998, the motivation-based model predicts an association between antecedents e.g., individual and situational variables and

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

138

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

motivation for participation, and a relationship between motivation for participation and consequences e.g., performance. Although the present study examined specically organizational commitment, environmental dynamism, and performance, other antecedent and consequence variables can be explored using the proposed model.2 The remainder of this section develops expectations regarding the relationships between the three types of motivation and both their antecedents and consequences. Antecedents and Motivation for Participation in Budgeting Organizational Commitment Organizational commitment is loyalty to the organization, and has been dened as the strength of an individuals identication with and involvement in a particular organization Porter et al. 1974, 604. Subsequent research see review by Ketchand and Strawser 2001 has distinguished between the continuance commitment and the affective commitment dimensions of organizational commitment. The continuance commitment dimension reects individuals desire to remain with their organization because departing costs are high. In contrast, Ketchand and Strawser 2001, 223 note that the affective commitment dimension reected in Porter et al.s 1974 denition is based on an individuals emotional attachment to an organization formed because that individual identies with the goals of the organization and is willing to assist the organization in achieving these goals emphasis added. Two key components of this denition pertain specically to the different forms of motivation. First, according to Deci and Ryan 2000, 235, a secure relational base provides a needed backdrop for intrinsic motivation. Individuals with high levels of organization commitment, and thus emotional attachment, are therefore expected to be more intrinsically motivated to participate. Second, identication with demanded behaviors reects individuals acceptance of the behavior as their own, i.e., the internalization of demanded behaviors Ryan and Deci 2000b. Hence, the degree to which individuals identify with the goals of the organization is expected to be positively associated with the autonomous form of extrinsic motivation. The relationship between organizational commitment and controlled extrinsic motivation is less clear given that controlled extrinsic motivation consists of two types of behavioral regulation, i.e., introjected and external regulation see footnote 1. Whereas introjected regulation reects some level of internalization of the demanded behavior, external regulation involves none Ryan and Deci 2000b. Studies by Gagn and Koestner 2002 and Gagn et al. 2004 nd that organizational commitment is positively associated with introjected regulation, but negatively associated with external regulation. Based on the above, we propose a nondirectional hypothesis of the effect of organizational commitment on controlled extrinsic motivation. Finally, consistent with Clinton 1999, who posits commitment as an antecedent of budgetary participation, it is expected that the stronger individuals identication with and their involvement in a particular organization, the higher the level of PB. Based on the foregoing, the related hypotheses are stated as follows: H1a: There is a signicant positive association between organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting. H1b: There is a signicant positive association between organizational commitment and autonomous extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting.

Task difculty was also measured as a third antecedent variable. It is omitted from the study due to the very low reliability of the measurement scale.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

139

H1c: There is a signicant association between organizational commitment and controlled extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting. H1d: There is a signicant positive association between organizational commitment and the level of participation in budgeting. Environmental Dynamism Environmental dynamism is dened as the degree to which factors in the organizations environment remain constant over time or continually uctuate Duncan 1972. According to Ryan and Deci 2000b, 70, the inherent tendency to seek out novelty and challenges, to extend and exercise ones capacities, to explore, and to learn typies intrinsic motivation. In the present context, it is posited that individuals intrinsic motivation to participate will be positively associated with environmental dynamism, to the extent that individuals view PB in a dynamic environment as novel and challenging. The current study further posits that in high uncertainty situations caused by a dynamic environment, managers may feel pressured to participate in order to obtain information to better cope with unanticipated events Brownell and Hirst 1986. Consequently, the extrinsic motivation is more likely to be of the controlled than of the autonomous type. Finally, consistent with Shields and Shields 1998, 60, who posit that environmental characteristics are antecedents of PB, we propose that environment dynamism is positively associated with PB. Accordingly, the related hypotheses are stated as follows: H2a: There is a signicant positive association between environmental dynamism and intrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting. H2b: There is a signicant negative association between environmental dynamism and autonomous extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting. H2c: There is a signicant positive association between environmental dynamism and controlled extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting. H2d: There is a signicant positive association between environmental dynamism and the level of participation in budgeting. Motivation and Participation in Budgeting Earlier studies e.g., Merchant 1981; Brownell and McInnes 1986 have examined the effect of PB on participants motivation to work toward budget attainment. Prior studies e.g., Mia 1988 have also examined how work motivation serves as a moderator in the relationship between PB and performance. However, no prior study has examined employees motivation to participate in the budgeting process, which is the focus of the current research. Although various forms of motivation may lead to different performance outcomes, research on motivation Vallerand 1997, 279 shows that those who are extrinsically motivated may be just as motivated to engage in a given activity as those who are intrinsically motivated. Hence, all three forms of motivation are expected to be positively associated with the extent of PB. The related hypotheses are: H3a: There is a signicant positive relationship between intrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and the level of participation in budgeting. H3b: There is a signicant positive relationship between autonomous extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and the level of participation in budgeting.

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

140

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

H3c: There is a signicant positive relationship between controlled extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and the level of participation in budgeting. Motivation and Performance The proposed model posits an association between three forms of motivation for PB and the individual participants performance. Research Vallerand 1997; Koestner and Losier 2002; Baard et al. 2004 provides evidence of positive consequences produced by both intrinsic and autonomous extrinsic motivations. In contrast, a negative relationship is most often observed between controlled extrinsic motivation and performance. Consistent with those ndings, the related hypotheses are stated as follows: H4a: There is a signicant positive relationship between intrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and performance. H4b: There is a signicant positive relationship between autonomous extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and performance. H4c: There is a signicant negative relationship between controlled extrinsic motivation for participation in budgeting and performance. Participation in Budgeting and Performance In general, the relationship between PB and performance has been equivocal. This has lead to research that examines the extent to which the relationship is conditional on other budgeting and/or nonbudgeting variables. For example, studies by Brownell 1985 and Govindarajan 1986 provide support for the hypothesis that the relationship between participation and performance is contingent upon characteristics of the environment. The present study does not examine and predict the effect of contingencies. Consequently, the hypothesized association between PB and performance is based on the review of empirical evidence. A meta-analysis by Greenberg et al. 1994 provides evidence of a positive relationship between PB and performance. Similarly, a study by Wagner 1994 nds that despite apparent inconsistencies in initial results of earlier reviews, research suggests that participation can have positive effects on performance. Thus, the following hypothesis is stated: H4d: There is a signicant positive relationship between participative budgeting and performance. METHOD Participants The survey was administered to 101 managers of a large international bank in Hong Kong. Because the sample is drawn from a single organization, external validity is limited. However, the focus of the present study was on the test of a general motivation-based model of PB. Thus, although the ndings of the study may not be generalizable to other organizations, it provides control over the potential confounding effect of unobserved heterogeneous practices that may be present across different rms Otley and Pollanen 2000, 486487. Sixty-one percent of the participants were male. Total years of work experience at the bank ranged from four to 30 years. The participants held management positions in a variety of departments at the branch level. Total years in a managerial position ranged from less than one year to ten years. Participants age ranged from 26 to 55. None of the demographic variables was signicantly related to any of the study variables.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

141

The survey was administered during two sessions of a training seminar attended by the managers. There were 51 managers at the rst session and 50 at the second. The participants were not compensated and participation was voluntary. Everyone who attended the seminar participated in the survey. No signicant differences in responses were found between the two groups. Therefore, the data were combined for statistical analyses. Measurement of Variables Organizational Commitment Organizational commitment was measured using the nine positively worded items from Mowday et al. 1979. A review of organizational commitment research by Ketchand and Strawser 2001 indicates that the nine-item version of the original questionnaire had relatively high reliability in prior studies e.g., Price and Muller 1981; Blau 1987; Nouri and Parker 1998, and it strongly correlated with the eight-item Affective Commitment Scale developed by Meyer and Allen 1984. This is consistent with ndings of others e.g., Carsten and Spector 1987; Farkas and Tetrick 1989; Settoon et al. 1996 that the six negative items in the original 15-item questionnaire measure an intent-to-quit factor. The word organization in the original instrument was replaced by the word bank.3 Participants were asked to respond to questions related to the degree to which they feel committed to their organization bank. A seven-point Likert scale was used, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Higher lower scores indicate a relatively higher lower commitment to the organization. Environmental Dynamism The instrument developed by Duncan 1972 was used to measure environmental dynamism. This measure has been used in prior accounting studies including Fisher 1996 and Chenhall and Morris 1986. Participants were asked to examine a group of eight environmental characteristics generally believed to be crucial to decision-making.4,5 Two items related to government regulation impacts of government regulation and constraints from bank regulators were excluded from the analysis because different branches of the same bank all resided in Hong Kong presumably operate under similar regulatory conditions. For each characteristic, participants were asked to indicate on a ve-point Likert scale how often they perceived the item changed. The scale items range from 1 never to 5 very often. Low high scores indicate a relatively static environment dynamic environment. Participation in Budgeting This study used the Milani 1975 instrument to measure participation. Prior studies e.g., Parker and Kyj 2006; Mia 1988; Brownell 1982 report good reliability for this scale. Participants were asked to rate their level of budget participation under each of six items on a ve-point Likert scale.6 The responses were coded so that higher lower scores reect a relatively higher lower level of participation.

5 6

Aranya and Ferris 1984 and Ferris 1981 made similar changes to the original questionnaire. For example, to measure commitment to the profession, the word organization was replaced by the word profession Aranya and Ferris, 1984. Item 6 negotiating was changed slightly to ensure the suitability of the instrument to bank managers. Specically, Purchasing, selling or contracting for goods or services, contacting suppliers, dealing with sales representatives was changed to Negotiating with customers on loans, deposits, etc. Item 8 on the original instrument referred to constraints from suppliers. Since this does not apply to bank managers, that item was reworded to read, constraints from bank regulators. Prior to the study, we ensured that the stated organization policy of the bank and the organizational culture at the bank allowed and encouraged PB. It is worth mentioning, however, that the perceived level of support for PB might differ at the branch level, which would result in some variance in the level of PB across branches.

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

142

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

Performance Performance was measured using the self-rating instrument developed by Mahoney et al. 1963, 1965. This scale has been used in many accounting studies including Hall 2008, Parker and Kyj 2006, Marginson and Ogden 2005, Chong and Chong 2002, Wentzel 2002, and Otley and Pollanen 2000. The instrument consists of performance measures along eight dimensions, as well as an overall performance measure. Participants were asked to self-rate their performance on a scale from 1 low performance to 9 high performance on each dimension and on the overall measure. According to Mahoney et al. 1963, 1965, the eight dimensions of performance account for about 55 percent of managerial performance. In this study, the regression of participants overall rating on their ratings of the eight individual dimensions resulted in 78.2 percent explained variation. Thus, the overall rating for each participant was used as the performance measure. Motivation for Participation in Budgeting The scales for the different forms of motivation were developed following SDT researchers e.g., Ryan and Connell 1989; Vallerand 1997, who argue that the perceived reasons for engaging in an activity provide a valid measure of motivation. According to Ryan and Connell 1989, 750, reasons are phenomenally accessible and they represent the primary basis by which individuals account for their actions. As such, they provide a direct means of assessing the perceived autonomy of ones actions. Similarly, Vallerand 1997, 284 argues that self-reports of individuals reasons for engaging in an activity provide a direct means of measuring motivation that is independent from its determinants and consequences. In this study, the different forms of motivation were measured by assessing individuals perceived reasons for PB. A total of seven items see the Appendix were used. The items were derived from the list of motivational, cognitive, and value attainment factors suggested by Locke and Schweiger 1979 and Locke et al. 1986. The three intrinsic motivation items referred to feelings of accomplishment, personal satisfaction, and belonging resulting from the mere act of participation. In contrast, the four extrinsic motivation items referred to participation as a means to an end. Autonomous extrinsic motivation was measured using two items that referred to PB as a means for the participant to set higher goals and to set goals on which he/she will be evaluated. The two controlled extrinsic motivation items referred to PB as a means for the participants to provide information and for the supervisors to better utilize information. Thus, while the autonomous items emphasized choice on the part of the participant, the controlled items implied external demands from the rm or the supervisor. For each of the seven reasons, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed that the item was a reason for participating in the budgeting process. Responses were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1, strongly disagree, to 7, strongly agree. RESULTS Descriptive Statistics Descriptive statistics for the measured variables are presented in Table 1. For each variable, a theoretical range and an actual range is presented, along with the mean and standard deviation. The correlation coefcients among the seven variables are also included in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the mean Intrinsic Motivation was 5.31, the mean Autonomous Extrinsic Motivation Autonomous-EM was 5.50, and the mean Controlled Extrinsic Motivation Controlled-EM was 5.16. These means were not signicantly different F-ratio 2.17, p 0.12. The two types of extrinsic motivation were positively correlated r 0.32; p 0.01, and Intrinsic Motivation was only positively correlated with Autonomous-EM r 0.28; p 0.01, but not with Controlled-EM r 0.14; p 0.15.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Behavioral Research In Accounting Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics (n 101)

Variable 1. Organizational Commitment 2. Environmental Dynamism 3. Participation in Budgeting 4. Intrinsic Motivation 5. Autonomous Extrinsic Motivation 6. Controlled Extrinsic Motivation 7. Performance Theoretical (Actual) Range 17 3.887.00 15 2.254.75 15 1.334.83 17 1.677.00 17 1.507.00 17 1.507.00 19 4.009.00 Mean (S.D.) 5.68 0.82 3.55 0.63 3.00 0.88 5.31 1.18 5.50 1.18 5.16 1.09 6.89 1.12 1 1.00 0.13ns 0.69*** 0.58*** 0.23** 0.40*** 0.29*** 1.00 0.13ns 0.02ns 0.20** 0.12ns 0.10ns 1.00 0.60*** 0.42*** 0.34*** 0.50*** 1.00 0.28*** 0.14ns 0.51*** 1.00 0.32*** 1.00 0.43*** 0.03ns 1.00 2 3 4 5 6 7

** and *** Signicant at the 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively. ns not signicant at the 0.10 level.

143

144

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

Statistical Analyses The model shown in Figure 1 was tested using the two-step structural equation modeling SEM procedure recommended by Anderson and Gerbing 1988. This approach has been employed in a number of accounting studies e.g., Bamber and Iyer 2002; Chong and Chong 2002; de Ruyter and Wetzels 1999; Maiga and Jacobs 2005. The procedure consists of rst evaluating the measurement model to adjust for measurement error. This step provides evidence of the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures. In the second step, the SEM is then estimated based on the results of the measurement model analysis. In order to achieve reliable maximum likelihood estimation, a sample-size-to-parameter ratio of 5 or more is recommended Hayduk 1987. Given the large number of parameters being estimated relative to the sample size in this study, the partial aggregation form of SEM was employed following de Ruyter and Wetzels 1999, Settoon et al. 1996, Bagozzi and Heatherton 1994, and Williams and Hazer 1986. According to that approach, the scale scores were used as indicators of the latent variables rather than the individual items. Specically, the indicator for each latent variable was rst computed by averaging the items for each scale, except for performance. Subsequently, each scales reliability and variance were used to incorporate measurement error into the SEM analysis. Measurement Model Exploratory factor analysis. Given that the three measures of motivation for PB were developed specically for the study, an exploratory factor analysis was performed to test if these three measurements represented three separate constructs. The principal-component method of factor analysis was used. The seven items were subjected to a factor analysis with varimax rotation. This yielded three factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The results see Table 2 show that the three Intrinsic Motivation items a, b, and c loaded on one factor, which accounted for 43.55 percent of the variance. Similarly, the two Autonomous-EM items d and e loaded on a second factor, which accounted for 24.60 percent of the variance. The two Controlled-EM items f and g loaded on a third factor, which accounted for 14.70 percent of the variance. In all, the three

TABLE 2 Factor Analysis on Motivation for Participation in Budgeting

Intrinsic Motivation 0.90 0.94 0.81 0.29 0.00 0.37 0.18 3.05 43.55% 0.88 AutonomousExtrinsic Motivation 0.07 0.12 0.15 0.92 0.94 0.14 0.15 1.72 24.60% 0.89 ControlledExtrinsic Motivation 0.02 0.05 0.09 0.08 0.22 0.77 0.86 1.03 14.70% 0.56

Item a. Feeling of accomplishment b. Sense of personal satisfaction c. Feeling of belonging and increased identication d. I am able to set higher goals e. I set the goals on which I will be evaluated f. For me to provide important information g. For superior to allow better utilization of information Eigenvalue Percentage of Variance Explained Cronbach Alpha

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

145

factors accounted for 82.85 percent of the variance. The Cronbach alpha for the Intrinsic Motivation, Autonomous-EM, and Controlled-EM scales were 0.88, 0.89, and 0.56, respectively. Conrmatory factor analysis. Conrmatory factor analysis CFA was rst performed on each conventional measure, and then on the measurement model as a whole, to assess convergent and discriminant validity. The initial model for organizational commitment OC did not provide an adequate t Chisquare df 27 153.84, p 0.01; GFI 0.75; AGFI 0.59; NFI 0.82; CFI 0.84. Following the re-specication procedure suggested by Anderson and Gerbing 1988, one item For me this is the best of all possible banks for which to work was deleted due to low standardized loading. The revised measurement model achieved an acceptable t Chi-square df 17 41.67; p 0.01; GFI 0.92; AGFI 0.83; NFI 0.95; CFI 0.97 with reasonable reliability 0.94 and all item loadings over 0.50. The initial model for environmental dynamism ED did not provide an adequate t Chisquare df 9 42.87, p 0.01; GFI 0.86; AGFI 0.67; NFI 0.47; CFI 0.49. Two items Actions of competitors and Keeping pace with technological advances were deleted due to low standardized loadings. The revised model provided an adequate t Chi-square df 2 5.27; p 0.07; GFI 0.97; AGFI 0.87; NFI 0.88; CFI 0.91. The reliability was 0.81 and the item loadings were all over 0.50. The initial model for PB PB provided an adequate t Chi-square df 9 29.21, p 0.01; GFI 0.92; AGFI 0.82; NFI 0.93; CFI 0.95. The reliability was 0.91 and the item loadings were all over 0.50. A conrmatory factor analysis was then performed on all the measures using scale average score to determine the overall t of the measurement model. All possible links were drawn between the seven constructs, which lead to a saturated model, i.e., degree of freedom was 0. The procedure suggested by Anderson and Gerbing 1988 was used to assess discriminant validity of the seven constructs shown in the theoretical model. First, the correlation was xed at 1.0 for pairs of constructs with high correlations. Following Bamber and Iyer 2002, the correlations over 0.45 OCIntrinsic Motivation; OCPB were xed at 1.0. Then, a Chi-square difference test was performed to compare the constrained and unconstrained models. The Chi-square difference test showed signicantly Chi-square 8.78 df 2, p 0.01 inferior t for the constrained model. This provides evidence of the discriminant validity of the constructs Anderson and Gerbing 1988. Structural Model Theoretical model t. The decision-tree framework for the sequential Chi-square difference tests SCDTs among nested models recommended by Anderson and Gerbing 1988 was used to determine the optimal model. The results of the procedure are shown in Table 3. The rst step consists of performing a Chi-square difference test between the saturated model and the theoretical model see Figure 1. The results of the comparison showed signicant difference p 0.01. The next step is to compare the theoretical model with the constrained model. When estimating the theoretical model, the coefcient estimate between ED and Controlled-EM path coefcient 0.06, p 0.66 and that between Controlled-EM and PB path coefcient 0.06, p 0.63 were not signicant. Therefore, the theoretical model was compared with a constrained model where these two insignicant links were constrained to 0. The Chi-square difference between the two models was not signicant p 0.19. The third step was to compare the constrained model and the saturated model. Although the result of the Chi-square difference test was signicant p 0.03, the constrained model provides an adequate t Chi-square df 7 15.88, p 0.03; GFI 0.96; AGFI 0.85; NFI 0.93; CFI 0.96. Thus, the tests of the hypotheses are based on the constrained model see Figure 2 where the path coefcients between

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

146

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

TABLE 3 Results of Sequential Chi-Square Difference Tests (SCDTs)

Chisquare 0 15.47 15.47 15.88 Change on Chi-square (p-value) 15.47 0.01 0.41 0.19

Model Step 1 Saturated Model Theoretical Model Theoretical Model Constrained Model: EDControlled-EM; Controlled EMPB Saturated Model Constrained Model: EDControlled-EM; Controlled EMPB

df 0 5 5 7

GFI 1 0.96 0.96 0.96

AGFI NA 0.79 0.79 0.85

NFI 1 0.93 0.93 0.93

CFI 1 0.95 0.95 0.96

Step 2

Step 3

0 15.88

0 7

15.88 0.03

1 0.96

NA 0.85

1 0.93

1 0.96

ED Environmental Dynamism; EM Extrinsic Motivation; and PB Participation in Budgeting.

ED and Controlled-EM, and between Controlled-EM and PB were constrained to 0.7 Hypothesis tests. Standardized parameter estimates for the constrained model are used to test the hypotheses. The results are shown in Figure 2. The standardized parameter estimates between OC and Intrinsic Motivation path coefcient 0.65, p 0.01, OC and Autonomous-EM path coefcient 0.30, p 0.01, OC and Controlled-EM path coefcient 0.57, p 0.01, and OC and PB path coefcient 0.57, p 0.01 are all positive and statistically signicant. These results are consistent with H1a, H1b, H1c, and H1d. As noted earlier, the path between ED and Controlled-EM path coefcient 0.06, p 0.66 is not signicant. The path between ED and Intrinsic Motivation path coefcient 0.13, p 0.19 is also insignicant. Thus, H2a and H2c are not supported. As predicted in H2b, the path between ED and Autonomous-EM path coefcient 0.28, p 0.01 is negative and signicant. The path coefcient between ED and PB path coefcient 0.19, p 0.02 is signicant but negative. This does not support H2d. Consistent with H3a and H3b, the path coefcient between Intrinsic Motivation and PB path coefcient 0.24, p 0.01 and between Autonomous-EM and PB path coefcient 0.20, p 0.01 are positive and signicant. As noted earlier, the path between Controlled-EM and PB path coefcient 0.06, p 0.63 is insignicant. Thus, H3c is not supported. As predicted in H4a and H4b, both Intrinsic Motivation path coefcient 0.35, p 0.01

7

According to the decision-tree framework proposed by Anderson and Gerbing 1988, when the Chi-square difference between the constrained model and saturated model is signicant, an unconstrained model i.e., a model with additional paths drawn compared with the theoretical model may be identied to replace the original theoretical model. Since no additional meaningful path could be identied in our theoretical model Figure 1, we decided not to continue with such re-specication. This decision is based on Anderson and Gerbings 1988, 416 recommendation that respecication decisions should not be based on statistical considerations alone, but rather in conjunction with theory and content considerations.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

147

FIGURE 2 Structural Equation Model with Standardized Path Coefcients Constrained Model

0.57*** 0.65*** Organizational Commitment 0.30***

Intrinsic Motivation 0.35***

0.24***

0.57***

Autonomous Extrinsic Motivation

0.20*** 0.32***

Participation in Budgeting

-0.13 ns Environmental Dynamism -0.28***

0.28**

Performance

-0.19**

-0.32*** Controlled Extrinsic Motivation

*** and ** Signicant at the 0.01 and 0.05 levels, respectively. The two links indicated by dotted lines were constrained to 0 due to insignicant coefcients. Chi-square [df = 7] = 15.88; p-value = 0.03. GFI = 0.96; AGFI = 0.85; NFI = 0.93; CFI = 0.96.

and Autonomous-EM path coefcient 0.32, p 0.01 are positively associated with Performance. In contrast, the path coefcient between Controlled-EM and Performance path coefcient 0.32, p 0.01 is negative. H4c is, therefore, supported. H4d is supported as well. The path coefcient between PB and Performance path coefcient 0.28, p 0.05 is both positive and statistically signicant. DISCUSSION The present study proposes a motivation-based model of PB from the perspective of individual participants. The model distinguishes among intrinsic motivation and the autonomous and controlled forms of extrinsic motivation for PB. In the tested model, associations are predicted

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

148

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

between two antecedents organization commitment and environment dynamism and participants various forms of motivation for participation. The different forms of motivation are also predicted to be associated with individual participants performance. The remainder of this section rst examines the results and discusses their potential implications. The studys limitations are then described, followed by suggestions for future research. Motivation for Participation in Budgeting There was no signicant difference across the levels to which participation was motivated by intrinsic motivation, autonomous extrinsic motivation, or controlled extrinsic motivation. Moreover, similar to the ndings of Ryan and Connell 1989, the two types of extrinsic motivation were positively correlated. This suggests that individuals can be motivated to participate by autonomous and controlled motivation simultaneously. This is consistent with Levesque and Pelletiers 2003 observation among a signicant percentage of their study participants. Antecedents and Motivation for Participation in Budgeting Organizational commitment was positively and signicantly associated with all three forms of motivation, as well as with the extent of PB. This nding indicates that individual variables can be important antecedents of PB. While the focus of research on participative budgeting has primarily been on environmental, organizational, and task variables Shields and Shields 1998, the present study suggests that individual factors may be equally important antecedents. In addition, the positive effect of organizational commitment on controlled extrinsic motivation suggests that the items we used to measure controlled extrinsic motivation might reect introjected as opposed to external regulation see footnote 1. Introjected regulation is in effect when the individual has taken in, but has not fully internalized the value of the behavior Gagn and Deci 2005. In the current context, managers may have partially accepted the value of PB as a conduit for the organization to obtain useful information. Environmental dynamism was negatively, but not signicantly, associated with intrinsic motivation. Recall that it was hypothesized that the association between these two variables would be positive to the extent that individuals perceived the dynamic environment as novel and challenging. One possible explanation is that this perception was counterbalanced by the contrasting view that a dynamic environment creates pressure for employees to participate in order to cope with the uncertainties of a constantly changing environment. In such a case, PB would be less likely viewed as autonomous, and intrinsic motivation would be undermined Deci and Ryan 2000. Consequently, the counterbalancing views may have resulted in a nonsignicant association between environmental dynamism and intrinsic motivation. As hypothesized, environmental dynamism was negatively correlated with autonomous extrinsic motivation. However, it was not signicantly correlated with controlled extrinsic motivation as we predicted. Another unexpected nding is that environmental dynamism was negatively associated with PB. The more participants perceived the environment to be dynamic, the lower was their level of involvement in the PB process. A possible explanation for these two unexpected ndings is that participants may have a poor understanding of the environment when it is dynamic. Consequently, they may be less likely to participate because they do not have the necessary knowledge of the environment to make a useful contribution. Indeed, Locke et al. 1986, 70 note that employees who nd themselves in such a situation will realize that they should not participate in the decision and will feel embarrassed or inadequate. Similarly, Hopwood 1973 argues that as environmental dynamism increases, the formal accounting system is less able to capture managerial behaviors that are needed to achieve organizational goals p. 11. Consequently, participating in the budgeting process which is a formal component of management accounting system could be viewed as less useful when environmental dynamism is high.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

149

Motivation for Participation in Budgeting and Performance The ndings suggest that both intrinsic motivation and autonomous extrinsic motivation were positively related to PB and performance. This is consistent with research for a review, see Ryan and Deci 2000b; Gagn and Deci 2005 that provides evidence that intrinsic motivation, as well as autonomous extrinsic motivation, produce positive consequences. Controlled extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, was not signicantly related to PB, and it was negatively associated with performance. The more participants were motivated by controlled extrinsic motivation to participate, the lower was the reported level of performance. These results indicate that there may be differences between the way individuals and the organization view PB. In particular, while the latter intends for PB to be viewed as a means to exchange information, employees in the current sample seem to view it as controlling. They were thus motivated by controlled extrinsic motivation, which negatively affected their performance. The results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, the scales for measuring different types of motivation were conveniently constructed using reasons for PB that were described in prior research. The three scales do not fully capture the breadth of those constructs. The operationalization of extrinsic motivation, in particular, was limited to only goal setting in the case of autonomous extrinsic motivation and information reasons in the case of controlled extrinsic motivation. Second, the study employed self-reported measures of motivation, participation, and performance. A multi-method approach would improve the validity of the ndings. Third, the sample of participants was drawn from a single organization. While this provides a homogeneous sample and eliminates some of the noise associated with a crosssectional study, it also limits the generalizability of the ndings. The evidence pertaining to different types of motivations for PB suggests several possibilities for future research. First, the present study did not examine other common reasons for participation, such as to improve coordination between subunits or to reduce job-related tension Shields and Shields 1998. Future studies can investigate the extent to which these reasons reect autonomous and controlled motivation, and their impact on performance. Second, the relationship between other antecedent variables and different forms of motivation can be studied. For example, future research can examine the impact of budget emphasis, information asymmetry, and budgetbased compensation on the different types of motivation. Third, Ryan and Deci 2000a, 64 note that, Given the clear signicance of internalization for both personal experience and behavioral and performance outcomes, the critical applied issue concerns how to promote the autonomous regulation of extrinsically motivated behaviors. Research can examine specic aspects of the participation process that lead to increased intrinsic motivation or more autonomous extrinsic motivation. While further research is needed before denitive conclusions can be drawn, the ndings of the current study suggest that studying the various types of motivation for PB may be useful for understanding its effectiveness, and the cognitive mechanism by which the information benets of PB are presumably obtained may be more complex than assumed since it may reect controlled forms of extrinsic motivation. APPENDIX Measure of Motivation for Participation in Budgeting* Below are a number of reasons why people participate in the budgetary process. Please indicate the extent of your agreement or disagreement to the following responses to the statement, I participate a. Because participation in budgeting gives me a feeling of accomplishment.

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

150

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

b. c. d. e. f. g.

Because participation in budgeting gives me a great sense of personal satisfaction. Because participation in budgeting gives me a feeling of belonging and increased identication with the bank. Because participation in budgeting is a means through which I am able to set higher goals. Because participation in budgeting is a means through which I set the goals on which I will be evaluated. Because participation in budgeting is a means for me to provide information that is important for my job. Because participation in budgeting is a means through which my superior allows for better utilization of information on the job.

* Participants responses were measured on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1, labeled strongly disagree, to 7, labeled strongly agree. Items a, b, and c are the intrinsic motivation reasons, d and e are the autonomous extrinsic motivation reasons, and f and g are the controlled motivation reasons.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. C., and D. W. Gerbing. 1988. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin 103: 411423. Aranya, N., and K. R. Ferris. 1984. A reexamination of accountants organizational-professional conict. The Accounting Review 59: 115. Baard, P., E. Deci, and R. Ryan. 2004. The relation of intrinsic need satisfaction to performance and wellbeing in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34: 20452068. Bagozzi, R. P., and T. F. Heatherton. 1994. A general approach to representing multifaceted personality constructs: Application to state self-esteem. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1 1: 3567. Baiman, S., and J. Evans. 1983. Pre-decision information and participative management control systems. Journal of Accounting Research 21 2: 371395. Bamber, E. M., and V. M. Iyer. 2002. Big 5 auditors professional and organizational identication: Consistency or conict? Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 21 2: 2138. Blau, G. 1987. Using a person-environment t model to predict job involvement and organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 30: 240257. Brownell, P. 1982. The role of accounting data in performance evaluation, budgetary participation, and organizational effectiveness. Journal of Accounting Research 20 1: 1227. 1985. Budgetary systems and the control of functionally differentiated organizational activities. Journal of Accounting Research 23: 502512. , and M. Hirst. 1986. Reliance on accounting information, budgetary participation, and task uncertainty: Tests of a three-way interaction. Journal of Accounting Research 24 2: 241249. , and M. McInnes. 1986. Budgetary participation, motivation, and managerial performance. The Accounting Review 61: 587600. Carsten, J. M., and P. E. Spector. 1987. Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: A metaanalytic test of the Muchinsky model. The Journal of Applied Psychology 72: 374381. Chenhall, R. H., and D. Morris. 1986. The impact of structure, environment, and interdependence on the perceived usefulness of management accounting systems. The Accounting Review 61 1: 1635. Chong, V. K., and K. M. Chong. 2002. Budget goal commitment and informational effects of budget participation on performance. Behavioral Research in Accounting 14: 6586. Clinton, B. D. 1999. Antecedents of budgetary participation: The effect of organizational, situational, and individual factors. Advances in Management Accounting 8: 4570.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

151

Covaleski, M., J. Evans III, J. Luft, and M. Shields. 2003. Budgeting research: Three theoretical perspectives and criteria for elective integration. Journal of Management Accounting Research 15: 349. Deci, E. L. 1975. Intrinsic Motivation. New York, NY: Plenum Press. , and R. M. Ryan. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press. , and . 2000. The what and why of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227268. de Ruyter, K., and M. Wetzels. 1999. Commitment in auditor-client relationships: Antecedents and consequences. Accounting, Organizations and Society 24: 5775. Duncan, R. B. 1972. Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly 17 3: 313327. Farkas, A. J., and L. E. Tetrick. 1989. A three-wave longitudinal analysis of the causal ordering of satisfaction and commitment on turnover decisions. The Journal of Applied Psychology 74: 855868. Ferris, K. R. 1981. Organizational commitment and performance in a professional accounting rm. Accounting, Organizations and Society 6: 317325. Fisher, C. 1996. The impact of perceived environmental uncertainty and individual differences on management information requirements: A research note. Accounting, Organizations and Society 21 4: 361 369. Gagn, M., K. Boies, R. Koestner, and M. Martens. 2004. How work motivation is related to organizational commitment: A series of organizational studies. Working paper, Concordia University. , and E. Deci. 2005. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior 26: 331362. , and R. Koestner. 2002. Self-determination theory as a framework for understanding organizational commitment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Canada. Govindarajan, V. 1986. Impact of participation in the budgetary process on managerial attitudes and performance: Universalistic and contingency perspectives. Decision Sciences 17: 496516. Greenberg, P., R. Greenberg, and H. Nouri. 1994. Participative budgeting: A metaanalytic examination of methodological moderators. Journal of Accounting Literature 13: 117141. Hall, M. 2008. The effect of comprehensive performance measurement systems on role clarity, psychological empowerment, and managerial performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society 33 2/3: 141 163. Hayduk, L. A. 1987. Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL: Essentials and Advances. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press. Hopwood, A. 1973. An Accounting System and Managerial Behavior. London, U.K.: Saxon House. 1976. Accounting and Human Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Ketchand, A. A., and J. R. Strawser. 2001. Multiple dimensions of organizational commitment: Implications for future accounting research. Behavioral Research in Accounting 13: 221251. Koestner, R., and G. F. Losier. 2002. Distinguishing three ways of being internally motivated: A closer look at introjection, identication, and intrinsic motivation. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research, edited by Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan, 101121. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. Lepper, M. R., and D. Greene. 1978. Overjustication research and beyond: Towards a means-ends analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In The Hidden Costs of Reward, edited by Lepper, M. R., and D. Greene, 109148. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Lepper, M. R., D. Greene, and R. E. Nisbett. 1973. Undermining childrens interest with extrinsic rewards: A test of the overjustication effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 28: 129137. Levesque, C., and L. G. Pelletier. 2003. On the investigation of primed and chronic autonomous and heteronomous motivational orientations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29 12: 15701584. Locke, E., and D. M. Schweiger. 1979. Participation in decision-making: One more look. In Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 1, edited by Staw, B., 265339. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. , , and G. P. Latham. 1986. Participation in decision making: When should it be used? Organizational Dynamics 14: 6579.

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

152

Wong-On-Wing, Guo, and Lui

Mahoney, T. A., T. H. Jerdee, and J. S. Carroll. 1963. Development of Managerial Performance: A Research Approach. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western Publishing. , , and . 1965. The jobs of management. Industrial Relations 4: 97110. Maiga, A., and F. Jacobs. 2005. Antecedents and consequences of quality performance. Behavioral Research in Accounting 17 1: 111131. Marginson, D., and S. Ogden. 2005. Coping with ambiguity through the budget: The positive effects of budgetary targets on managers budgeting behaviours. Accounting, Organizations and Society 30 5: 435456. Merchant, K. 1981. The design of the corporate budgeting system: Inuences on managerial behavior and performance. The Accounting Review 56 4: 813829. Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1984. Testing the side-bet theory of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations. The Journal of Applied Psychology 69 3: 372378. Mia, L. 1988. Managerial attitude, motivation and the effectiveness of budget participation. Accounting, Organizations and Society 13: 465475. Milani, K. 1975. Budget-setting, performance and attitudes. The Accounting Review 50: 274284. Mowday, R. T., R. M. Steers, and L. W. Porter. 1979. The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior 14: 224247. Nouri, H., and R. J. Parker. 1998. The relationship between budget participation and job performance: The roles of budget adequacy and organizational commitment. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23 5/6: 467483. Otley, D. T., and R. M. Pollanen. 2000. Budgetary criteria in performance evaluation: A critical appraisal using new evidence. Accounting, Organizations and Society 25: 483496. Parker, R. J., and L. Kyj. 2006. Vertical information sharing in the budgeting process. Accounting, Organizations and Society 31 1: 2745. Penno, M. 1984. Asymmetry of predecision information and managerial accounting. Journal of Accounting Research 22 1: 177191. Porter, L. W., R. M. Steers, R. T. Mowday, and P. V. Boulian. 1974. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. The Journal of Applied Psychology 59: 603609. Price, J. L., and C. W. Muller. 1981. Professional Turnover: The Case of Nurses. New York, NY: Spectrum. Ronen, J., and J. Livingstone. 1975. An expectancy theory approach to the motivational impact of budgets. The Accounting Review 50: 671685. Ryan, R., and J. Connell. 1989. Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 749761. , and E. L. Deci. 2000a. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic denitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25: 5467. , and . 2000b. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist 55 1: 6878. , and . 2002. An overview of self-determination theory. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research, edited by Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan, 333. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. Settoon, R. P., N. Bennett, and R. C. Liden. 1996. Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. The Journal of Applied Psychology 81 3: 219227. Shields, J. F., and M. D. Shields. 1998. Antecedents of participative budgeting. Accounting, Organizations and Society 23: 4976. Vallerand, R. J. 1997. Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 29, edited by Zanna, M. P., 271360. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Wagner, J. A., III. 1994. Participations effects on performance and satisfaction: A reconsideration of research evidence. Academy of Management Review 19 2: 312330. Wentzel, K. 2002. The inuence of fairness perceptions and goal commitment on managers performance in a budget setting. Behavioral Research in Accounting 14: 247271.

Behavioral Research In Accounting American Accounting Association

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Participation

153

Williams, L. J., and J. T. Hazer. 1986. Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnover models: A reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods. The Journal of Applied Psychology 71: 219231.

Behavioral Research In Accounting

Volume 22, Number 2, 2010 American Accounting Association

Copyright of Behavioral Research in Accounting is the property of American Accounting Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Ebook PDF Elementary Algebra 4th Edition by Michael III SullivanDokumen41 halamanEbook PDF Elementary Algebra 4th Edition by Michael III Sullivansean.cunningham518Belum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Black-Scholes Excel Formulas and How To Create A Simple Option Pricing Spreadsheet - MacroptionDokumen8 halamanBlack-Scholes Excel Formulas and How To Create A Simple Option Pricing Spreadsheet - MacroptionDickson phiriBelum ada peringkat

- BDS PDFDokumen5 halamanBDS PDFRobinsonRuedaCandelariaBelum ada peringkat

- Module 2 - Math PPT PresentationDokumen28 halamanModule 2 - Math PPT PresentationjhonafeBelum ada peringkat

- Culture and Cultural GeographyDokumen6 halamanCulture and Cultural GeographySrishti SrivastavaBelum ada peringkat

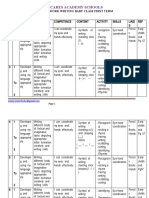

- Scheme of Work Writing Baby First TermDokumen12 halamanScheme of Work Writing Baby First TermEmmy Senior Lucky100% (1)

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics Quarter 2 - Module 1Dokumen21 halamanUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics Quarter 2 - Module 1Allaine's ChannelBelum ada peringkat

- Secured Steganography To Send Seceret Message: Project ID: 1029Dokumen33 halamanSecured Steganography To Send Seceret Message: Project ID: 1029Pravat SatpathyBelum ada peringkat

- OP-COM Fault Codes PrintDokumen2 halamanOP-COM Fault Codes Printtiponatis0% (1)

- Mock Test: Advanced English Material For The Gifted 2020Dokumen13 halamanMock Test: Advanced English Material For The Gifted 2020Mai Linh ThânBelum ada peringkat

- Solutions of 6390 Homework 4Dokumen12 halamanSolutions of 6390 Homework 4mukesh.kgiri1791Belum ada peringkat

- Professional Scrum Master I Simulator Test 1 PDFDokumen8 halamanProfessional Scrum Master I Simulator Test 1 PDFRahul GandhiBelum ada peringkat

- Sequential Circuit Description: Unit 5Dokumen76 halamanSequential Circuit Description: Unit 5ramjidr100% (1)

- Second Form Mathematics Module 5Dokumen48 halamanSecond Form Mathematics Module 5Chet AckBelum ada peringkat

- Smart Meter For The IoT PDFDokumen6 halamanSmart Meter For The IoT PDFNaga Santhoshi SrimanthulaBelum ada peringkat

- Hibernate-Generic-Dao: GenericdaoexamplesDokumen1 halamanHibernate-Generic-Dao: GenericdaoexamplesorangotaBelum ada peringkat

- Finding The Process Edge: ITIL at Celanese: Ulrike SchultzeDokumen18 halamanFinding The Process Edge: ITIL at Celanese: Ulrike SchultzeCristiane Drebes PedronBelum ada peringkat

- Appa Et1Dokumen4 halamanAppa Et1Maria Theresa Deluna MacairanBelum ada peringkat

- Remaking The Indian Historians CraftDokumen9 halamanRemaking The Indian Historians CraftChandan BasuBelum ada peringkat

- Handling Qualities For Vehicle DynamicsDokumen180 halamanHandling Qualities For Vehicle DynamicsLaboratory in the WildBelum ada peringkat

- WSDL Versioning Best PracticesDokumen6 halamanWSDL Versioning Best Practiceshithamg6152Belum ada peringkat

- Researchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignDokumen6 halamanResearchpaper Parabolic Channel DesignAnonymous EIjnKecu0JBelum ada peringkat

- Microelectronic CircuitsDokumen22 halamanMicroelectronic CircuitsarunnellurBelum ada peringkat

- EBCPG-management of Adult Inguinal HerniaDokumen12 halamanEBCPG-management of Adult Inguinal HerniaJoy SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Q2 Week7g56Dokumen4 halamanQ2 Week7g56Judy Anne NepomucenoBelum ada peringkat

- Verification ofDokumen14 halamanVerification ofsamuel-kor-kee-hao-1919Belum ada peringkat

- GVP CmdsDokumen3 halamanGVP CmdsShashank MistryBelum ada peringkat

- Reflection EssayDokumen3 halamanReflection Essayapi-451553720Belum ada peringkat

- Telephone Operator 2021@mpscmaterialDokumen12 halamanTelephone Operator 2021@mpscmaterialwagh218Belum ada peringkat