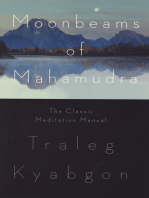

Mahamudra - Traleg Rinpoche

Diunggah oleh

meltarJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Mahamudra - Traleg Rinpoche

Diunggah oleh

meltarHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Traleg Rinpoche: Mahamudra Talk 1

In Tibetan Buddhism, particularly in the Kagy tradition, the tradition to which I belong, the concept of mahamudra is very important. The word mahamudra literally means great seal or great symbol. In Sanskrit, maha means great and mudra means seal or symbol. Mahamudra basically refers to ultimate reality, to shunyata or emptiness, but the word mahamudra also refers to the very nature of mind. Ultimate reality, which is mahamudra, is all-pervasive and non-differential and does not fall on either side of subject or object because of its all-pervasive nature, and that concept is not different from the nature of mind itself. From this point of view, the nature of mind is different from the mind that we normally refer to in ordinary discourse. Normally, when we talk about the mind, what we mind is the mind that thinks, which wills, which experiences emotions and so forth, but when we talk about the nature of mind we are talking about something which goes beyond all that. Because the nature of mind is indistinguishable from ultimate reality, which is emptiness, it no longer relates to the thinking process, or the process of willing, or the process of the experience of emotions. It goes beyond all that. Therefore, the nature of the mind and ultimate reality are known as mahamudra. There is that sense of nonduality. But I think that in order to understand mahamudra, we need to place it in the context of the Buddhist tradition generally. From the point of Buddhism, the ultimate aim is to achieve nirvana or enlightenment. Nirvana is achieved as a result of having purified ones mind, having overcome certain defilements and obscurations of the mind which afflict the individuals consciousness. As long as defilements such as anger, jealousy and all kinds of egocentric tendencies exist, as long as there are defiling tendencies of the mind, then sentient beings, human beings, continue to experience a sense of dissatisfaction, frustration, suffering and so forth. These defilements exist in the first place because human beings generally have a very misguided way of understanding themselves, of understanding the nature of what they consider to be their own self. Human beings generally tend to think that the self is something immutable, lasting and unchangeable. This is not available in direct experience, but is a mental construct. Based on this, one then sees everything from the point of view of a very stable, unchanging, permanent self. Of course, this can manifest in relation to various philosophical and religious ideas regarding the nature of the self, the notion of

the soul, but it does not have to have anything to do with philosophy or religion. Even if one does not believe in immortality of the soul, nonetheless, almost everybody has the notion that it is me who feels happy, who feels sad, who experiences joy and unhappiness and there is something called the self which endures the varities of experiences that I have. I may feel good, or I may not feel good, I may grow old. There is the feeling that there is something called me, essential me, which endures all these experiences. The experiencer who has the experiences is somehow more lasting, more permanent than the experiences themselves. When Buddhism talks about egolessness or selflessness it does not mean that ego as such does not exist at all, as an empirical thing. Of course it does. But the almost instinctive feeling that we have that says there is something called ego which has this permanent endurance that is unreal, that is a simple mental construct, because ego, like everything else, is impermanent. As long as one does not have that understanding, then one would continue to grasp onto things, hold onto things, cling onto things, because this tendency which human beings have, in terms of clinging onto the self, would automatically lead to clinging onto other things, things which are outside the self. As long as human beings have the tendency to believe in a permanent self, then automatically, one would want to obliterate anything that is considered to be threatening to that notion of a self or one would want to pursue those things which one believes would promote the solidification of that notion of a self: aversion and excessive desire. Even aversions such as hatred, resentment, hostility and so forth are a form of clinging. From the Buddhist point of view, once one starts to realize that this socalled self or ego is non-enduring, non-permanent, non-eternal, then gradually one starts to cling less and as a result of that ones experience of frustration, dissatisfaction and so forth would decrease. This is not to say that clinging, grasping, craving and so forth are the same as desire. Over the years in the course of talking to Westerners, I have found that many of them have the notion that Buddhists really aim towards the extinguishment of all desires. That is no true. What Buddhists really talk about is the idea of overcoming clinging, grasping, craving.

As I mentioned before, clinging can manifest even in the form of clinging onto the idea of begin resentful of someone, clinging to the notion of not being able to forgive, not being able to accept certain things, holding onto ones feeling of hostility and resentment of other people. Desire, on the other hand, can be either positive or negative. Clinging, grasping, craving can never be positive. Clinging onto anything, at least from a Buddhist point of view, is always unhealthy. But we have to have desire to be even able to operate as human beings. Without desire we will never get anywhere. Even from a spiritual point of view, unless we have the desire to sit on our cushion and meditate, we will never get anywhere. Unless we have the desire to want to attain enlightenment or become a Buddha we will never get anywhere. Unless one has desires, nothing can be achieved. From a Buddhist point of view there is basically nothing wrong with having the desire to want to have a good family, to want to look after ones children, to want to have a good relationship, to want to have a good partner in life, to want to get a good job or even to want to keep ones job. The problem arises when those desires become exaggerated. When desires become transformed into forms of clinging, forms of grasping and, at the same time, if desires manifest in the form of craving, then it becomes a problem. So I think it is important to realize that Buddhism does not promote the idea of abandoning desires altogether. What Buddhism encourages is the idea that all forms of craving, grasping and clinging, which are exaggerated forms of desire, have to be abandoned not because there is something morally wrong with them, but because, ultimately, they are the cause of unhappiness. One may think that clinging onto things somehow or other would promote ones happiness, but that is misguided. Such misguided ideas come from having this mistaken notion about the self, from thinking that the self is a permanent, enduring entity rather than realizing that the self, just like the experiences which the self endures, is impermanent, mutable and therefore ephemeral. So, from the Buddhist point of view, if one is to overcome the experience of suffering or dukkha, then one has to have proper insight into the nature of the mind or into the nature of the self, because as long as one clings onto this mistaken notion about the self, then one would experience varieties of suffering.

We have to understand that suffering, from a Buddhist point of view, is quite different from what we normally mean by suffering. When Buddhists say, everything is suffering, that does not mean that Buddhists have the understanding that everything is terrible and bleak, there is no future for anybody and we cannot have any sense of enjoyment of happiness. Suffering is understood in a broader context, in the sense that, as long as we cling onto the idea of an enduring self, even the happiness which we experience, the pleasure which we experience, is always going to be something impermanent, something which only lasts for a short time, precisely because of clinging and grasping. The happiness and pleasures that we experience are not denied. Buddhists do not say we do not experience happiness or pleasure. But, because of our grasping or clinging, even when we have experiences of happiness and pleasure, they are only temporary. As human beings, our mind is dominated by the concept of an enduring self so when one has the experience of happiness and pleasure, the way in which such experiences are pursued is in relation to something that is external to the self. How does one pursuer happiness in relation to things that are external to the self? Wanting to get a job that pays well and thinking that will bring permanent happiness; thinking that if one marries the right person, then permanent happiness will be found; thinking that if one has children who are good an pleasant to have around, then permanent happiness will be discovered. From the Buddhist point of view, the reason why everything is seen as suffering is precisely because of having that misplaced conviction, having that misplaced understanding in relation to what would really bring happiness, what would really bring pleasure in ones life. As long as one thinks that long-lasting happiness or long-lasting pleasure can be obtained only in relation to things other than the self, then no happiness or pleasure really is going to be lasting, because ones whole idea or experience of happiness is contingent on other things. Whether things which would promote ones happiness persist or not is dependent on all kinds of external causes and conditions which are mutable, changeable, impermanent and which, for that reason, bring about a sense of frustration and dissatisfaction. Therefore, everything is suffering. If one wants to attain lasting happiness, then that can be achieved only through self-transformation, through changing ones attitudes, through changing ones understanding of the self. Without that, no matter how much one wants happiness, no matter how much one pursues happiness, happiness is going to be elusive. One think that happiness can be achieved or discovered in

relation to things that one possesses or things that one does, but not in relation to the way one exists, in the way one lives ones life, not in relation to ones own being. From a Buddhist point of view the reason one needs to gain proper insight into the nature of the self is precisely happiness, real lasting happiness, simply comes from just that: having insight into the nature of the self, into the nature of the mind, and realizing that thinking there is this self, this unchangeable, permanent, enduring entity, is a misconception. Furthermore, with this misconception all kinds of delusions and obscurations of the mind arise, which in turn inhibit the individual from experiencing and perceiving reality. So right from the beginning Buddhism has emphasized the importance of purification of the mind, of how important it is to eradicate the defilements and obscurations of the mind, of how important it is to have proper self-knowledge, because that is the only way that real, lasting happiness can be attained. That same emphasis exists in the later teachings, in the Mahayana teachings, and also in the teachings of mahamudra which Im going to be discussing. I think it is important to talk about these things because the teachings of mahamudra make sense only in relation to understanding these fundamental Buddhist insights. Right from the beginning, Buddhism sees spiritual salvation only in understanding the nature of ones own self, in realizing what kind of individual one is, and in seeing how certain emotional conflicts arise due to certain misconceptions. Those are the two veils: the veil of conceptual confusion and the veil of emotional conflict. This means that our thinking and our experience of emotions are intimately related. We cannot separate the two. Due to certain misconceptions regarding what we understand ourselves to befor example, the notion that there is something called an enduring, permanent selfall kinds of emotional conflicts follow. By changing the conceptual structures of the mind even emotions become transformed. In the West we have the notion that emotions and thoughts are very different, that emotions and reason are completely opposed to eachother. From a Buddhist point of view this is not true. In fact, what we believe in, how we think, has direct influence on the mind of emotions that we experience. Fundamentally, all our beliefs are tied up with our notion of the self. A Buddhist would say that our very dogmatic attitudes towards things or people, dogmatic attitudes toward people who belong to other religions, other races, and so forth all reflect ones own notion of the self. Either they

are seen as threatening or they are seen as something that would help consolidate the notion of the self. But once that whole idea of the self as being an enduring permanent entity is overcome then all the defiling tendencies of the mind would subside, both on the conceptual as well as the emotional level. I would like to stop here and have a discussion. Q: There is no doubt that outside things do contribute to happiness. They are impermanent, but they still contribute to our peace of mind and wellbeing. Does that mean its not real? A: No. From a Buddhist point of view, it is legitimate to have the desire to want to have a good job, have a nice family, be able to drive a car that runs, rather than one that breaks down and causes further misery, or have a spouse who is supportive and understanding, rather than one who abuses you. All that is important. But because of clinging and grasping, one normally has the tendency to think that these will bring about permanent happiness. So what happens when the spouse stops loving you or when the car breaks down or when you lose the job? Then one would feel suicidal, because one thinks, Im nothing, other than the job that I have, or Im nothing without such and such a person. Everything that one believes oneself to be is defined by these things or people that one finds oneself with. And that is mistaken. That is what Buddhists mean when they say real lasting happiness will be obtained through self-knowledge, through real understanding of oneself, and not from other things. Which is not to deny the existence of temporal happiness. When Buddhists say everything is suffering, that does not mean there is no pleasure or happiness in life outside oneself. There are such pleasures and happiness, but they are only temporary, precisely because they are dependent upon causes and conditions external to the self. Even when one has a really good relationship, lets say, one is in love with a spouse and the spouse loves you and everything is hunky dory, if the spouse dies unexpectedly, then happiness disappears and suffering sets in. One has to have a proper understanding of impermanence and real appreciation of impermanence would come from realizing the impermanence of the self. What we regard as the self which we think is unchanging and immutable, in fact, is always in process. And that could be a good thing. So from a Buddhist point of view self-growth can take place precisely because the self is not some kind of immutable unchanging entity. Otherwise any kind of change or transformation in the self would only

be apparent, not real, because the real self is seen as something that is unchanging and permanent. Q: How do you distinguish between a desire that is valid, and clinging and grasping? A: Just from not clinging, but desiring. For example, if you want to get a job, if you want too much, then youll make a fool of yourself during the interview, precisely because you want it so much. Or if you desire somebody and you think, He is so good, he is so fantastic, and the more you think about it the more you get worked up, that in itself might make the other person stand back and not have anything to do with you. Thats really what clinging, grasping, craving means. Buddhists are not promoting a notion of social breakdown, that parents should stop loving their children because it is a form of attachment and that children should stop loving their parents because it is a form of attachment or that husbands should leave their wives as quickly as possible because that also reflects a form of attachment. That whole idea is a misunderstanding in so far as there is nothing wrong with these things as long as one keeps everything in perspective, as long as one does not become attached and there is no clinging-grasping involved. Q: In that situation when one is clinging, say to anger or grief, and one watches oneself clinging, how does one work themselves out of it? A: In Buddhism that is why meditation is so important. Through meditation we become more aware. If one becomes more and more aware of the tendencies that one has, then even without making any deliberate effort to drop certain habits that one has, they will naturally drop away. There is a story about a thief who was wandering around in the mountains. There were no houses with riches or anything like that, so he was feeling a bit desperate when he discovered a cave. He went in and there was a meditator sleeping. He started to take whatever he could while this meditator was sleeping. As he was about to leave the mouth of the cave the meditator woke up and asked, What are you doing? The thief said, Theres been nothing to steal so I had to come here. But Im sorry. I know you are a meditator and I shouldnt be doing this. The thief was feeling really embarrassed and said to the meditator, Look, I feel so bad, Ill do anything. I should change my ways. I would like to become a spiritual person. You, being a meditator, maybe you could teach me a few things. But dont tell me to stop stealing, because that is what I do and I cant help it. But

you can teach me anything else and Ill do it. The meditator said to him, Dont worry about it. Next time when you steal, just be aware that you are stealing. After about two weeks the thief came back to the meditator and says, What have you done! I cant steal anymore. So if one has that awareness, even if one is not deliberately trying to stop certain negative habits, just being aware would naturally wear them down. In fact, if one tries too hard to drop certain habits, then those habits may become more solidified. Awareness is more important than actually making too much effort into not being certain things. For example, if we try too hard to be nice, we end up not being nice. We become nice by becoming more aware of not being nice, rather than trying too hard to be nice. Q: Are the mind and the nature of mind two separate things? They are. And the mind, I presume, is the logical mind that we perceive the world around us. Can that mind become aware of the nature of mind? And if not, how do you become aware of the nature of mind? A: The nature of mind is not different from our thinking mind as such, yet at the same time they are not identical. It is because one does not have insight into the nature of the mind that ignorance exists. Ill talk about this later, but the nature of mind is no different from the nature of thoughts and emotions that we have, but because we do not have insight into the nature of thoughts and emotions, we do not have insight into the nature of the mind. How do we gain insight into the nature of the mind? That comes from awareness. Awareness is the key. For example, when you do meditation, without thinking Why do I think about these trivial things, why do they come up in the mind? Why do certain emotions arise? Why do I have certain thoughts and emotions arising?not thinking like that, not judging them to be bad or terrible things that you have to get rid of, but simply being aware of them, that is the mahamudra approach. From the mahamudra point of view, if you judge certain things to be bad or terrible, then that is a form of clinging as well. If you think, I have to get rid of these terrible things that I think about, these terrible negative emotions, then that in itself is a form of clinging. So just be aware of what arises in meditation. Q: Is the difference between the mind and the nature of the mind like the difference between the consciousness and the subconsciousness?

A: I suppose we could say it is, in so far as we are not conscious of them. If one has more awareness of the nature of the mind then much of our experience of dissatisfaction and so forth would subside. Q: Is the nature of the mind more like emotions and the way you behave, and the mind is more like what you are thinking? A: Ill be talking about this later, but the nature of the mind is said to be completely nondifferentiated, spacious, and is the basis of all of our experiences, the source from which all of our experiences arise. But in itself, it is not differentiated. So the nature of mind, unlike our thoughts and emotions, does not exist as an entity. Often it is compared to space. Space itself is not something like an entity, but it is because of space that clouds and so forth arise. Clouds have definable characteristics, whereas space itself doesnt. But space makes it possible for the clouds to be there in the first place. Sometimes the mind and the nature of the mind are compared to waves or the surface of the ocean and the ocean depths. One may perceive the waves, the activities on the surface of the ocean, but not actually realize the stillness and infinity of the depth of the ocean. The mind is said to be the same thing. On the other hand the nature of the waves and the nature of the depth of the ocean is the same thing, it is still water. In a similar kind of way, our thoughts and emotions have the same nature as the nature of the mind, but because of our ignorance we cannot appreciate that. If you are a psychologist or try to understand the mind, then you try to understand the mind in relation to its definable characteristics, in relation to thoughts and emotions. But there is another way of understanding the mind, which has to do with understanding the nature of the mind, which goes beyond that in a sense. Maybe I should put it another way. From the Mahayana point of view, we talk about two levels of truth, relative truth and absolute truth. What is absolute truth? Absolute truth is emptiness. What that means is that things do not have enduring essence. There is no such thing as substance or something that we can refer to as being the essence of things. On the other hand that does not mean that things do not exist. The nature of things, all the chairs and tables that we perceive, their nature is emptiness. The problem is in not perceiving the emptiness of the chairs and tables, not realizing that they lack enduring essence. How do we realize that? We realize

that through these very things, chairs and tables. Emptiness does not exist over and above them, emptiness exists as the nature of these things. The same thing with the mind. We understand the nature of the mind through our thoughts and emotions. Q: If the self has no enduring quality, what element is it that is therefore transmitted in the Buddhist belief in reincarnation? A: A Buddhist would say that precisely because there is no enduring self that there is rebirth. Buddhists do not really believe in reincarnation, Buddhists believe in rebirth. Each rebirth is quite complete. Nothing that is unchangeable gets transferred from one state of existence to another. Certain dispositional properties of the mind become transferred from one state of existence to another. Often, in the traditional Buddhist teachings, the example of plants are used. You would not say that a seedling is the same as a mature plant, but nonetheless there is the obvious transference of dispositional properties from the seedling to the mature plant. In a similar kind of way, certain dispositional properties of our previous existence get transferred to our present state, but nothing that is unchanging survives during this period. A seedling is one thing and a mature plant is something else. We were all in an embryonic stage at the beginning of our life, but as regards the relationship between the embryo and the mature people that we have become, obviously something from the embryo is transferred, but we are not the embryo. From that point of view, it is the same with the notion of the self or ego. Buddhism says that our notion of the self gets reinforced in two different ways. One is through habit, through an innate tendency to think that my self is something permanent, which comes with the birth of consciousness. The other is that the same idea gets reinforced through learning. So if we are brought up in an environment which promotes the notion of a soul or some kind of unchanging psychic principle, then that would reinforce our idea of the self as something permanent and nonchanging. So it comes from two sources. One is innate, the other is learned. Q: So in an embryonic state we would have at least a beginning of a self, which is then developed and reinforced as the embryo develops and we grow older. But in fact that notion of self is an illusion.

A: To understand the self from a Buddhist point of view means we have to understand it from the point of view of the middle way. A Buddhist does not deny the existence of an ego or of the self. The self exists, on the relative level, but the self is an ultimate entity, as some kind of unchanging permanent thing does not exist. But that does not mean people do not have egos or that ego is totally illusory. I think some people have interpreted the Buddhist notion of selflessness or egolessness from that point of view, which is not true. We do have egos, we do have selves, but the self, as a Buddhist would say, is an aggregate, a skandha. We tend to think that the self is somehow distinguishable from our memories, our emotions, our thoughts, our attitudes. Somehow or other the self remains at a distance, observing all these things going on, or enduring all these experiences, but the experiencer is at a remove from what is going on. But Buddhists say that is exactly what the self is. The self is the memories, thoughts, emotions, concepts, attitudes. Put them together and you have a self. And if you take away all of thatin Buddhism we do this as an exerciseif we disassociate ourselves completely from our body, our memories, our thoughts, emotions, attitudes, our backgrounds, experiences, if we divorce ourselves from all these things, what remains? Nothing. We are something, somebody, precisely because we have those things. Without them, it is nothing. And that is emptiness, I suppose. But when we have them together, that is an aggregate, that is whats called skandha in Sanskrit. Q: You know that the concept of there being an I or an experiencer is just that and you know that you have another concept that there may not be anymore there, but how do you get past just having an idea about it to knowing it? A: Basically from observation, through meditation. The continuity of the self is there. That is not denied. What is denied is something that is unchanging, permanent. Q: Im not going to identify with my body, any of my emotions, any of my experiences, but I still have this thought that there is someone there who is experiencing. A: Well there is. Thats the thing. There is, and that is the ego, ego which is changing and impermanent rather than something unchanging and permanent as we normally assume it is. Ego as an empirical thing exists, but it is a product of causes and conditions, just like our body. That is what Buddhists

mean by egolessness. It doesnt mean it doesnt exist, as so many people assume. It exists, but it doesnt exist as an ultimate entity. It has been said that western thought talks about the ego, while Buddhism does not and, in fact, it teaches the nonexistence of ego. But even western psychology does not make any reference to the concept of soul or anything unchanging. When western psychologies talk about the ego, they are not talking about anything unchanging, permanent, immutable. So in some ways, there are similarities there. It is also said that western psychology talks about building up the ego, whereas Buddhism teaches how to break down the ego. But Buddhism, as much as western psychology, also talks about building up self-confidence and feelings of self-worth. Buddhism does not say that through the experience of egolessness we should feel nothing, that we should feel bad about ourselves. But through understanding of the self as not being permanent, a real appreciation of the self can be attained because then the self is something that can be transformed rather than something that is unchanging and permanent. Q: Ive often wondered why Buddhism uses the noun form emptiness. It seems to me that the word emptiness creates the illusion that emptiness is an entity itself. A: Nagarjuna has said that if we cling onto the idea of emptiness as being something, then that is worse than clinging onto the idea that everything has enduring essence. He says, To think that things have enduring essence is as foolish as a cow, but to think that everything is nonexistent or completely empty is even worse. That is the middle view. The idea is that emptiness does not mean things do not exist. Emptiness is not discovered over and above existing things, emptiness is discovered as being the nature of all things that exist. Its not something that is a negative thing, its not total voidness, or anything like that. Q: Something we say all the time that I have found quite useful is, change your mind. You might say, Ill have a cup pf coffee and then, Ive changed my mind and its quite simple. Sometimes when Im angry Ill remember and just change my mind, just do something different. That catches the idea that its not permanent. A: Thats an interesting comment. From a Buddhist point of view, thoughts and emotions are so intimately related that by changing our thoughts we change our emotions. For example, the thought that your lover is having an

affair makes you angry or jealous, but if you realize that that was unfounded and not true, then jealousy or anger subsides immediately. In the west, these days, there is this tendency to think that you can deal with emotions directly, but from a Buddhist point of view, we actually can have more success with the changing of our emotions only if we change our thoughts. If we think differently, then we will feel differently and we will experience our emotions differently as well. So in that sense, yes, by changing our mind we will be a different person. As we know, the most upset person is the one who thinks too much. You cant sleep, you cant eat, constantly these thoughts are nagging at you and you get more and more worked up. TALK 2 Having discussed the general Buddhist understanding of the concept of the self and what needs to be done in relation to establishing a proper concept of the self so that one would be able to gain real insight into it, now I will talk about the Mahayana Buddhist concept of Buddha-nature, which is called tathagathagarbha in Sanskrit. The tathagathagarbha theory, the theory of Buddha-nature, was presented by the Yogachara school of Mahayana Buddhism. In order to understand the mahamudra view of the nature of mind it is essential to have some understanding of the concept of Buddha-nature, because the mahamudra concept of the nature of mind is based on this essential Mahayana notion that all sentient beings have the potential and opportunity to become fully awakened. The concept of tathagathagarbha has been rendered differently in different English translations of various Mahayana texts. Some translate this particular concept or word as the womb of enlightenment others as matrix yet others have translated it as seed of enlightenment. In any case, when this concept was introduced into Mahayana it was seen as quite revolutionary, because up to that point Buddhism only talked about egolessness, lack of self. When the notion of Buddha-nature was introduced into Mahayana literature some Buddhists felt that this was, in a way, a perversion of the original teachings because Buddha-nature implies that there is something in the continuum of the consciousness which, in fact, is unchanging and can act as the basis upon which one can develop on a spiritual level. There is this potential for enlightenment in everyone. In some of the Mahayana literature Buddha-nature is called the great selfthe ego being

the little self. In some Zen literature it is also called the mind of no mind. When this idea was promoted by the Yogacarins it seemed to many that the whole idea of an unchanging self was being re-introduced into Buddhism, therefore people were very skeptical. Many Buddhists tried to explain this new teaching regarding the concept of the essential self. Some teachers said that the teachings on Buddha-nature are taught not because they are really true, but so that certain people who have been frightened by the notion that there is no self would find some comfort in thinking that there is something afterall, which is called Buddha-nature. For many Mahayana teachers, particularly the so-called sunyavadins or teachers who emphasized the importance of emptiness, it was just an expedient method to enable people to come to some understanding about themselves on a gradual level. After coming to have some understanding of Buddha-nature, they would then gradually abandon the whole notion of Buddha-nature and eventually come to accept the teachings on emptiness, which is the ultimate truth. For many other Buddhist teachers, particularly the Yogacarins who of course promoted the concept, Buddha-nature is not just a theory, not just a concept, but exists in reality and is the essential nature of all human beings. What this concept suggests is that for human beings, or sentient beings generally, as far as their mind is concerned, there is an element of consciousness which has never been defiled, which has remained pure, right from the beginning and precisely because of the purity of this element of consciousness it is possible to attain enlightenment. Without it, that would not be possible. The Yogacarins said that the defilements exist but only on a relative level because ultimately the mind is pure by nature. In terms of early Buddhism the Buddha in some of his early sutras in fact made references to the mind being undefiled, pure and so forth, but these were just references. He did not elaborate on this. We could say that the Yogacarins elaborated on that concept. The mind itself is completely undefiled, but what they call adventitious defilements arise. The word adventitious is used in order to suggest that defilements and obscurations of the mind are not essential to the mind itself, but arise due to causes and conditions. These defilements exist only on the

relative level, because on the ultimate level the mind itself is totally pure and undefiled and has been right from the beginning. Now, if the mind itself or an element of the mind or consciousness has not been defiled, right from the beginning, then the question might be asked, From where do the defilements arise? From what source? TO answer that, the Yogacarins introduced the notion of alayavijnana. That word is normally rendered into English as storehouse consciousness, but some translate it as fundamental consciousness, while Professor Guenther translates it as substratum of awareness. In any case, the wordalayavijnana was introduced into Mahayana teachings by the Yogacarins because they felt it had to be proposed as the basis of all our delusional experiences. This is the basic source from which all the obscurations and defilements arise. It is also the source from which one has this mistaken notion of self-existing, unchanging, permanent self. As the English rendition this Mahayana term as storehouse consciousness suggests, all of our experiences in terms of our karmic traces and dispositions are stored in the alayavijnana. Nothing, in fact, gets wasted. Everything remains dormant on an unconscious level and, when the appropriate time and situation arises, then the karmic traces in the mind would give rise to certain appropriate experiences. According to Yogacara philosophy, defilements arise from the alayavijnana, but the mind itself understood from the point of view of tathagathagarbha or womb of enlightenment is pure and non-defiled. That is, in fact, the ultimate aspect of the mind. The relative aspect of the mind understood from the point of view of the storehouse consciousness, is defiled. So the defilements in the mind exist only on the relative level. From the ultimate point of view the mind is completely pure. Some of the teachers who expunded this theory went so far as to suggest that tathagathagarbha or Buddhanature has four aspects: pure, blissful, permanent, and nontemporal and great self. Those of you who are familiar with conventional Buddhist teachings would know how radical this whole notion is. Traditionally, it is said that the mind is impure because of the defilements; there is no bliss, only suffering because of the defilements and due to clinging, grasping, and craving; nothing is permanent in terms of the mind or the self, everything is subject to change and is therefore mutable, but the Yogacarins say that Buddhanature is permanent. The last characteristic is great self, but Buddhism as we know has rejected all notions of a permanent, immutable self.

So the Yogacarins say the tathagathagarbha has these four attributes of being pure, blissful, permanent, and manifesting as the great-self. Now this might lead people to think that the tathagathagarbha theory is not different from the notion of the atma in Hindu tradition, which is normally translated as the soul or great self, because the atma is also understood to be permanent, blissful, et cetera. But according to Yogacara masters that is not the case. When it is said that Buddhanature is permaenent this is not saying that the tathagathagarbha is some self-existing reality, some kind of immutable entity. It does not meant that there is something that is actually existing and has some endurance, but permanent only in relation to the aspect of emptiness. The nature of tathagathagarbha, the womb of enlightenment, is emptiness. And because emptiness is not subject to change, it is therefore permanent. So these Mahayana teachers distinguished the notion of Buddhanature from the atma theory. They did not want to posit this concept as having some kind of self-existing or inherent existence. The phrase womb of enlightenment or seed of enlightenment suggests that tathagathagarbha exists only on a dormant level or as a potential. Again, different interpretations arose regarding this. Some say that it is called the seed or womb of enlightenment because it suggests that sense of dormancy or potentiality, rather than actuality. If this is the case, then tathagathagarbha is to be realized over a long period of time, after overcoming appropriate or characteristic obstacles on the path. The tathagathagarbha exists as a potentiality only. Yet others interpreted this in a radically different way. They said no, tathagathagarbha exists in all sentient beings. The lement of the consciouness which is non-defiled in ordinary sentient beings is no different from that of enlightened beings. Therefore sentient beings are originally enlightened, they only do not realize they are enlightened. That is the only problem, so ignorance lies in not realizing that. The tathagathagarbha, the womb of enlightenment exists not just in potentiality, but in actualiy. It is already there. These two different streams of interpretation exist both in Chinese and Japanese Buddhism, in relation to Zen. The teaching which said that the tathagathagarbha exists only in terms of potentiality is called Zen of the dcotrines, while the teaching which said that the tathagathagarbha exists in

its complete form even in unenlightnened ordinary sentient beings is called patriarichal Zen. We have the same two different kinds of interpretation in Tibetan Buddhism also. Some traditions interpret the concept of tathagathagarbha to mean that it exists as a potentiality for enlightenment, rather than enlightenment as such. Other traditions such as the teachings on mahamudra and Dzogchen or maha ati interpret it to mean complete enlightenment. Enlightenment is already present in its fullest form, nothing has to be added. If proper insight is gained into the nature of the mind, which is the same as tathagathagarbha, then there is nothing that has to be attained. It is more a question of realizing what one already possesses, rather than trying to improve on something through practice, through meditation, through embarking upon the spiritual path. These two traditions are normally referred to as the gradual and instantaneous schools of practitioners, the gradualists emphasize the importance of having to spend a lot of time developing that innate quality of the mind, which is non-defiled, and the spontaneists saying that there is nothing that one needs to do. In fact even meditation itself is not something that one does in order to improve the mind. Rather, meditation is done in order to strip away the layers of veils, the layers of defilements. But nothing needs improving, nothing needs to be added. Sometimes in mahamudra and in Dzogchen teachings it is said that nothing needs to be subtracted or added to, everything is complete in itself. In mahamudra teachings Buddha-nature is identified with the nature of mind. The very nature of the mind is said to non-defiled and complete. The nature of mind of ordinary sentient beings who are afflicted with varieties of obscurations and defilements is not different from the mind of enlightened beings. There is absolutely no difference. So the practice is not one of gradually working through ones karmic traces and dispositions and overcoming appropriate obstacles on the paths and stages, as it is in Mahayana teachings, but rather of allowing the mind to be. If one is able to allow the mind to be and not make any effort, not even the effort to become enlightened, if through practice of meditation one is able to allow the mind to be in its natural statethat is what is called in mahamudra teachings: in its natural statethen one would realize that one is already enlightened. Enlightenment is not something one has to attain. Enlightenment comes from being, from being in ones own authentic condition, without any contrivances.

It is said that through the practice of mahamudra one does not use any methods to change or transform the mind. The question is not of transforming the mind as much as it is of allowing the mind to reveal itself, because the nature of the mind itself is already perfect, complete and totally non-defiled. Therefore enlightenment is not achieved, as it has been said in oneself to be in ones own natural state. Then all the defilements would naturally become self-liberated. Self-liberated is a technical word used in mahamudra teachings and also in Dzogchen. The idea here is that, unlike the gradual approach of using the gradual approach of using different antidotes in order to overcome certain obstacles on the path, there are no antidotes that one needs to use, because all the delusions and obscurations of the mind would naturally become selfliberated if one is able to rest the mind without any contrivances, without trying to change it, without trying to transform it, without even trying to make it become more still, more clear, more translucent, more calm, more tranquil and so on. Without doing any of that, if one simply exercises pure awareness, observes what arises in the mind in terms of thoughts and emotions, does not judge them, does not pursue positive thoughts and emotions or shun the negative ones, but is able to simply let whatever arises in the mind to be, then according to the mahamudra traditions the thoughts themselves can become part of meditation. Thoughts and emotions may continue to arise, but they will no longer disturb the stability of the mind if one is able to maintain a pure sense of awareness. From the mahamudra point of view, the way in which one realizes the nature of the mind is not from shunning thoughts and emotions, but from letting them be, because if one is able to allow the mind to be in its natural state, then when thoughts and emotions arise, the nature of these thoughts and emotions would be revealed as having the same nature as the nature of the mind. Therefore another technical term used in mahamudra teaching is ordinary mind. Instead of thinking that Buddhahood is attained through transforming the mind or through becoming something greater than what one already is by trying to overcome ones negative thoughts and emotions, if one simply relates to the ordinary mind itself, ordinary mind meaning the mind which has experiences of all kinds, then during meditation, when thoughts and emotions arise, even if they are of a negative nature, if pure awareness is applied, then the nature of the negative thoughts and emotions would be revealed as having the same nature as the nature of the mind.

One of the mahamudra prayers says that the nature of thoughts is dharmakaya. Dharmakaya, meaning the nature of the mind, is not different from ultimate reality, so the nature of the thoughts is dharmakaya. Dharmakaya or ultimate reality is not to be found somewhere else, existing over and above the delusions which are already present in the mind. If proper awareness is applied by seeing the nature of the delusions, one would understand the nature of the mind, which is of course equated with the attainment of enlightenment. From the mahamudra point of view, because enlightenment is already present one should not concern oneself too much with abandoning this and trying to acquire that, unlike the traditional Mahayana approach to the path and meditation where one tries to abandon certain negative tendencies and replace them with positive ones, such as trying to overcome ones bad karma so that one would be able to create good karma and then be able to realize Buddhahood. One does not concern oneself with such an approach. What one has to do is practice meditation in such a way that the mind is left alone. One is not trying to use antidotes in order to overcome obstacles in meditation, one is not trying to transform the mind or use any kind of contrivances. One allows the mind to be in its own natural state. This is the so-called spontaneous approach, gcig charba in Tibetan. The gradual approach is called rimgyi ba, which means step-by-step approach to enlightenment. Enlightenment is not something that can be attained straight away, it takes a lot of effort and a lot of time. According to some Mahayana teachings it takes three countless eons to achieve enlightenment, so it is not an easy task. The instantaneous approach on the other hand says that because enlightenment is already present all one needs to do is to enter into that mind state, the state of enlightenment. It is not a question of going through different stages. Some teachers have noted that the gradual and instantaneous approaches may be able to reconcile their differences if one understands that when spiritual insights occur they occur instantaneously, but that there are many different kinds of spiritual insights that one can obtain, so these insights may occur over a period of time. Even though insights as they occur may be instantaneous, nonetheless these varying degrees of insight would be happening over a period of time. Therefore in a sense it is gradual also.

When the Mahayana teachings say that it takes three countless eons to become enlightened maybe that should not be taken too literallythis is according to some of the teachers who reconcile the differences between the gradual and the spontaneous approaches. Maybe it does not mean that it literally takes three countless eons to attain enlightenment, but because of the Mahayana concept of bodhichitta, of having to adopt infinite compassion to want to liberate all sentient beings, one generates the thought that until all sentient beings are enlightened one would not want to become enlightened. One has to develop such an attitude, but to develop that attitude and to think that one would like to remain in the samsaric condition for as long as it takes to liberate all sentient beings does not mean that the bodhisattva actually remains in the samsaric world for three countless eons, or for an indefinite period of time. If the bodhisattva has generated the relevant bodhisattva attitude, then that bodhisattva may attain enlightenment in a short period of time. So understood that way, it is said that there is no real contradiction between the approach of the gradualists and the non-gradualists. Even for example the teachings which explicitly set out the five paths and ten stages of the bodhisattva, of the Mahayana practitioner even these teachings which explain in great detail how each of the paths are traversed and how one gets transferred from one level of the bodhisattva to the next should not perhaps be understood in a too literal sense of having to spend so long a period of time going through the five paths and ten stages. The paths and stages can be traversed within ones own lifetime. Mahamudra teachings and the ones who try to reconcile the two different traditions emphasize the importance of aiming towards achieving enlightenment in ones own lifetime. Enlightenment is not something that one works towards in terms of accumulating good karma or merit as it is called over a long period of time and hoping that at some future time in one of ones future rebirths one would become enlightened. Enlightenment should be attained on the spot. When one sits down to practice on the meditation cushion ones does not think, Im just an ordinary sentient being with so many delusions and defilements. I do not have the ability to attain enlightenment. I have to do with breaking down certain negative karmic tendencies and gradually stripping the mind of defilements. Then at some future time I might become enlightened. Instead, one has to think, Enlightenment is accessible right now.

Mahamudra teachers are always pronouncing the importance of not distancing oneself from the state of enlightenment, of not thinking that enlightenment is something superior, something transcendent, something that is not really within ones reach at the moment. One should think of enlightenment as imminent, already present. By dropping ones defilements, which include such negative thoughts as distancing oneself from enlightenment, one would attain enlightenment on the spot, during meditation. Even to think of Buddhahood as being something so different, something totally independent of the samsaric condition, is a form of discrimination. And the mind should not discriminate in that way. By not discriminating, by not judging, by not placing evaluations on ones experiences but allowing the mind to be, then one attains enlightenment. All the delusions become self-liberated. One does not deliberately get rid of the defilements or the obscurations of the mind. They become self-liberated, purely through awareness. I think Ill stop here and we can have a discussion. Q: You talked about mahamudra being a spontaneous or instantaneous enlightenment compared to a gradualist approach. What makes the difference between being enlightened in one instance and not in another? A: The mahamudra masters actually do not say that there is a real conflict between the gradualist approach and the instantaneous approach because when spiritual insights occur they occur instantaneously, but on the other hand insights occur over a period of time in terms of intensity and so on. So in a sense there is a sense of gradualness about it. What the mahamudra teachers say is that the gradualness does not have to do with many lifetimes. It is not necessary that one has to devote so many lifetimes to practice, before one achieves enlightenment. According to mahamudra, even the Mahayana teachings which talk about the paths and stages, teachings which claim that it is necessary for the bodhisattva to spend three countless eons before attaining enlightenment, should not be taken literally. It simply refers more to the attitude of the bodhisattva then what it, in fact, the case. The bodhisattva, due to his or her infinite compassion, cares so much about the sufferings of ordinary people and so wants to postpone enlightenment. That is their mental attitude, but that does not mean that they would in fact, end up spending three countless eons before attaining enlightenment. So they say that even the teachings which set out detailed descriptions of the path and stages should not be taken too literally.

In that way you can reconcile the two traditions of gradualist and instantaneous approaches. Q: So its just a difference in emphasis in the motivation at the point when you sit down to meditate? A: Yes. Even if you have this concept of Buddha-nature, if one has the gradualist approach, then one may see Buddhanature as being more like a seed of enlightenment or potentiality for enlightenment, rather than Buddhanature being a fully developed enlightened aspect of the mind as it is now. Q: I find it difficult to pinpoint the difference between the instantaneous approach and the gradualist one. It seems to me that the practice is very similar. A: The gradual approach think of enlightenment as occurring in the future and the instantaneous approach thinks of enlightenment as being present now: it is only delusion which stands in the way, it has nothing to do with transformation of the mind or improving on anything. The mind in relation to its nature is already perfect. Dzogchen is another tradition which emphasizes the instantaneous approach. Dzogchen, great perfection, means simply that the mind as it exists is perfect itself. It is only due to ignorance due to delusions that one does not realize it. Enlightenment does not mean that the mind has become transformed, as much as that delusion, which stands in the way, has been removed. Once that is out of the way then one realizes ones own nature is perfect, that nothing needs to be added or subtracted from, as is said in the mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings. Subtracted means removing the defilements or delusions. But even teachings such as mahamudra and Dzogchen, which emphasize the instantaneous approach, try to reconcile the differences between the two traditions. They do not say that the gradualists are wrong. What they do is interpret the gradualist approach, the teachings which say that in order to become a fully enlightened Buddha first of all you need to adopt a bodhichitta or bodhisattva outlook and traverse the five paths and ten stages of the bodhisattva, then eventually this would culminate in the attainment of full Buddhahood and normally it would take three countless eons to do that. The mahamudra teachers and Dzogchen teachers have reinterpreted this to mean that in reality it does not mean it actually takes three countless eons to achieve Buddhahood, but according to Mahayana teachings which emphasize compassion so much, to develop this attitude involves having infinite

compassion for others, therefore such a bodhisattva has the attitude of not even wanting to attain enlightenment in a great hurry, that one would like to postpone ones enlightenment. But as Trungpa Rinpoche once said in his teachings, even if the bodhisattva does not want to become enlightened, he or she would become enlightened in spite of himself or herself, even without trying. Q: Why should it be a disadvantage to wish to become enlightened? Surely you are instantly more useful if you are enlightened than if you are not. Whats the idea of putting it off? A: The idea is that one does not want to enter nirvana prematurely. One wants to be in the world helping others. Q: Is that a consequence of not being available? A: Yes. But according to certain Mahayana teachings, and this includes Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings, samsara and nirvana are not so different. Sometimes it has been said that samsara is nirvana and nirvana is samsara. That does not mean samsara and nirvana are identical, what it means is samsara and nirvana have the same nature, which is emptiness. In that sense entering into nirvana does not mean going into some kind of totally different or transcendent realm, far from the empirical world that we live in. Nirvana is here right now if one knows how to attain it. So it is not something that takes place outside of space and time. Q: So where does the thought of wanting to put off ones enlightenment come from? A: That comes from compassion. Achieving enlightenment for ones own sake without thought of others is considered to be non-Mahayanist because Mahayana Buddhism puts so much emphasis on compassion. For that reason. Q: I see preliminary practice as a more gradual practice. Would you recommend for somebody to focus purely on doing mahamudra or on doing both mahamudra and preliminary practice? A: In the Kagyu tradition we do preliminary practice, we emphasize that very strongly, and we also practice mahamudra. But the preliminaries are performed with the intention to want to realize mahamudra in this life. Preliminary practices are not done with the intention to want to become enlightened in the distant future at some later date. As some of the

mahamudra teachers have said, the practices of the preliminaries help to thin out the defilements. For that reason they are practiced. But all the while one is doing the preliminaries one should have the mahamudra view, which is that enlightenment is within ones grasp and it can be attained. It is not something that is too exalted or out of ones reach. One can do the preliminary practices with the mahamudra view, instead of thinking that with the preliminary practice one is slowly wearing down the negative karma and, if one is lucky, at some future date one may become enlightened. Q: It is possible to grasp onto the idea of becoming enlightened? A: Yes. From the mahamudra point of view we should not be grasping onto any kind of idea, even the thought of enlightenment. When the mind is not grasping, when its not clinging onto anything, including the notion of having a tranquil mind, a peaceful mind, or grasping onto the notion of getting rid of thoughts, negative thoughts and emotions, then one realizes enlightenment. Q: Can one do meditation on ones own or does one need a teacher? A: It is important to have a teacher, but we have to realize that the teacher does not mean what in the west people think gurus to be. Basically having a teacher is to have a relationship with somebody and because the teacher has more experience than you, then you can work with the person. But that does not mean that someone has to be ultimately dependent on the teacher. For that reason, in fact, in mahamudra teachings it is said that the teacher has two aspects, relative and ultimate. The ultimate aspect of the teacher is Buddha-nature, or the nature of the mind itself. Thats the ultimate teacher. The relative teacher is the human one. Through the human teacher one comes to realize the ultimate teacher, which is the nature of the mind itself. Q: Im not familiar with the preliminary practices. A: The preliminary practices are normally, in Kagy tradition, what we call the four foundation practices. One is doing prostrations, another is called mandala offering, the third is Vajrasattva and the fourth is practice of devotion to the lineage. These are conducted in order to overcome certain obstacles. For example , doing prostrations can work with ones sense of egocentricity. With prostrations for example, westerners find the fact that you prostrate demeaning. Even though you are not prostrating to any individual as such,

just the simple fact of doing it is a bit too much. On the other hand, in order to show our humility we do that. People kneel in church, people kneel to pray, so its not foreign. Even in the west doing prostrations or kneeling reflects that attitude of humility, which is, of course not the same as lack of confidence or of self-worth. It works in terms of dismantling ones ego-centric attitudes so that one becomes more open. Mandala offering works with the sense of generosity so that you give up clinging-grasping and Vajrasattva is for purification of the mind. Devotion to the lineage to build up confidence in what one is doing. For example, if you are practicing something which has been put together by some crackpot who woke up one morning and thought he or she spoke to god who said this is what you should do, obviously that is not as credible as a tradition which has been based on authentic transmission from teacher to student, so there is a real valid transmission which has been preserved. So building confidence in that with ones devotion to the lineage. Thats what one does with the preliminary practices. Q: Could you say something about the relationship between ethical practices and meditation? A: In Buddhism we talk about cultivating wisdom through reflection, through contemplation, through meditation, and you cultivate compassion in terms of your actions, in terms of how you relate to others. In the early Buddhist teachings these are set out in the so-called paramitas, which also promote the whole idea of the three trainings of morality, wisdom, and meditation. Q: Meditation is really seen as the link between compassion and wisdom. In order to do both properly, one needs to practice meditation. From the mahamudra point of view actually, it is said that meditation is in some ways more important than concerning oneself too much with the practice of compassion because unless one has certain insight into oneself, unless one has certain understanding of ones own mind, then even if one is trying to do something which is good or worthwhile, it may in fact be perverted due to ones own delusions and lack of insight. It is said that through meditation in fact ones capacity to help others would come naturally. If one is able to have proper understanding of oneself, then one would have proper understanding of everything else. From the mahamudra point of view to understand the nature of the mind is to understand all

things because there is no separation, there is nonduality. If one has that experience of nonduality then compassion would stem forth naturally. It is not something that one has to deliberately cultivate. It would come. But generally, unlike what some people in the west think, Buddhismbecause of its emphasis on meditationdoes not undervalue the importance of engagement in the real world, helping people, doing whatever is necessary to alleviate others suffering. Which is very important. As the Buddhist nun Aya Khema said, Compassion can move mountains, but without wisdom you dont know which mountain needs moving. That sums it up nicely, in terms of the importance of both. Q: Is mindfulness essentially without language? I can be self-conscious of myself, but that will always be with a form of language following myself around. The idea of mindfulness seems to be something which transcends language. A: I suppose thats true in a way. Mindfulness is really involved with an object. You use certain objects so that you can practice mindfulness. From a Buddhist point of view mindfulness should give rise to awareness. It is very difficult for a beginner to be aware. You do not just become aware, but through the practice of mindfulness it is possible to develop awareness. Awareness comes from the practice of consistent mindfulness. You use an external object or you use the breath or you use your senses to practice mindfulness, so you are constantly going back to the object of mindfulness and not allowing your mind to run off in all directions. Mindfulness helps to anchor the mind so that it does not get too indulgent in thoughts, and language too. But from a Buddhist point of view mindfulness is something that becomes transcended through development of awareness. Once awareness develops, then one does not need to be mindful. Mindfulness is a deliberate thing whereas awareness is more spontaneous. Q: If just by being in the presence of a teacher you become emotional, what is actually happening? A: In Tibetan Buddhism we have this notion, this concept called auspicious coincidence. It is in a way similar to Jungs idea of synchronicity. For example if you hear Buddhist teachings it may strike a chord in you. Auspicious coincidence does not mean it is something accidental, that it just happened. The cause lies in ones own past and because of that now it has come to fruition, in a sense.

Q: What comes to fruition? Is it something from the past? A: In terms of ones past karma. From a Buddhist point of view nothing which is significant happens accidentally. If you hear something and that gives rise to certain emotions, then that does not mean you just happened to be there and, all of a sudden it just happened. Another expression used is karmic connection, whatever that means. Thats the phrase westerners use, but the concept is the same as what we call auspicious coincidence. As lamas keep on saying, there are millions and millions of people in the west and only a very few take an interest in Buddhism. Why so? From a Buddhist way of understanding, the ones who take interest in Buddhism have some kind of karmic propensity already, that is why. It doesnt happen just like that. The interest in Buddhism, for example, does not just happen. It has happened because of ones karmic propensity, which is already set in motion. Q: Is that from previous lives? A: Past lives, generally speaking from Mahayana point of view. Thats one way of understanding. But to be Buddhist or to practice Buddhism one does not have to believe in rebirth or anything like that. Thats not essential. What one needs to believe in is what Buddhism says about what causes suffering and how to overcome it. If we do that, then thats the essence, thats the most important thing. There are certain auxiliary concepts in Buddhism, concepts such as rebirth which are part of Buddhist teachings as well. But they are not essential. Q: In talking about the four characteristics of Buddha-nature you explained how the term permanent is interpreted in such a way that it is seen as being nonsubstantial. Could you interpret the term great self? A: It is the great self precisely because it is not some kind of metaphysical entity. It is the great self only because it represents the whole qualities of enlightenment which are already present within ones own mind. Because of that it is the great self, but not the great self as the atma concept suggests. Q: About the emotional response that is some kind of connection to whatever in your previous karma, how does one deal with it? A: Just accept it and let it be. Q: How can one come to terms with a situation like grief?

A: From a mahamudra point of view, one has to allow oneself to feel the grief, and then let go. Not suppress it, not encourage it, but when it arises one experiences it, and then let go. Q: How can you do that without becoming self-indulgent? A: Through awareness. There is nothing wrong with the feeling of grief. That is another thing. After doing meditation even if one has been doing meditation for a number of years, at least from a Buddhist point of view particularly from a mahamudra point of view, one should not think that one should go beyond all experiences of emotion. Emotions may still arise, but one experiences them differently and one deals with them differently, through the practice of meditation. That is really what is the most important thing. Even if you meditate, if a loved one dies then the appropriate emotion to experience is grief. If you dont grieve, theres something wrong with you. But to go on and on and not be able to let go, then it becomes a problem. Even if one is meditating, if some tragedies happen in ones life or tragedies happen to others, emotions arise but they are managed better because they dont overwhelm the person as much as if one was not meditating. Meditation should not lead the person to become like a piece of wood. Q: So you dont need to understand a karmic connection to understand where its coming from so you can try and transcend that emotion? A: You can transcend it by letting go, by not worrying about it. Not worrying is letting go, worrying is grasping. Thats what it is. From a Buddhist point of view, particularly from a mahamudra point of view, we should not be asking too many questions about why certain emotions or thoughts have some into the mind, but rather how they arise. How the emotions arise, how they affect us, that is really more important than looking for causes because you can come up with so many different explanations in terms of why and you can never be sure which one is correct. I think the existence of so many different psychotherapies proves that. Each form of therapy has a different explanation as to why certain emotions or certain neuroses arise. But that does not mean that is not important, we can still ask those questions and try to understand in terms of why, but it is more fundamental and more important to understand how they arise and how they affect us.

The question that should really concern us is more the question of how? not why? When you ask the question how? it is immediate. You can perceive it, its happening. When you start to ask why? its in the past. Then you start to look into causes. Thats why asking how? is more important and more beneficial. You were saying that when you hear Buddhist teachings emotions arise. You should be looking at how those emotions arise and how those emotions affect you, rather than thinking, Is it karmic connection or am I seeing the teacher as a father figure? So not concerning oneself too much with that, but with what type of emotions arise and how they affect you. Thats important. Even in terms of meditation, when emotions arise, it is more important to think of how they arise, rather than why they arise. Q: Whenever a certain type of music is played, and its the bagpipes believe it or not, I get an irrepressible urge to cry and it overwhelms me. I dont know how A: Thats how. Q: Okay. I feel very sad and I wait for it to go. A: Thats it. Its good to be aware of that. Q: It doesnt stop it. A: Thats not the point. Talk 3 The teachings of mahamudra are basically drawn from two streams of Mahayana thought, one being the Yogacara system and the other the teachings of the sunyavadins, who promoted the idea that ultimate reality is emptiness. Within the Buddhist tradition generally, one needs to eradicate certain defilements and obscurations of the mind in order to realize the ultimate truth or ultimate reality. The most effective way to achieve that goal is through the practice of meditation. Generally speaking, two different types of meditation are engaged in. One is called shamatha, or meditation of tranquility, and the other is called vipashyana, or meditation of insight. Through practice of meditation of tranquility the meditator learns how to quieten the mind so that it becomes more focused, more resilient, more aware and less susceptible to distractions. Meditation of insight on the other hand is usually conducted in an analytical

form. Therefore, while the practice of meditation of tranquility encourages the mind to become more calm and less disturbed by conceptual thoughts, meditation of insight uses these thoughts in order to gain certain insights such as realization of the fact that there is no enduring or permanent immutable self. Conventionally, meditation of tranquility is presented in a way which suggests that as the mind becomes more focused the meditator could enter into different levels of concentration, of absorptions. So as discurcive thoughts subside, the mind would go into different levels of absorptions. Once one has perfectd shamatha, if one engages in analytical meditation, then thinking no longer gives rise to conceptual confusions as it normally does, but it gives rise to different insights. It is said that Buddhist meditation is regarded as being different to other traditions only because of the practice of meditation of insight, since other traditions also have techniques of quieting the mind, techniques that help the mind to become more focused. But it is through the practice of meditation of insight that one comes to the realization that there is no such thing as an enduring or permanent self, or that there is no such thing as enduring essence in physical and mental phenomena, or in physical and mental properties. Mahamudra also makes use of these two different techniques of shamatha and vipashyana, but according to mahamudra teachings to go through different levels of absorptions or concentrations is not important. It is sufficient for one to have stabilized the mind. Even if one has not achieved any ultimate state of concentration, even if one has not managed to obtain any level of absorption, nonetheless if the mind has become more stable and less susceptible to distractions then one can proceed with the practice of meditation of insight. Here also the practice of meditation of insight according to mahamudra is quite different from the conventional approaches. In the Mahayana tradition one normally uses the analytical method to understand the lack of essence in all things, realizing that everything that exists in the physical and mental realm is a product of causes and conditions. Nothing exists in a self-sufficient way therefore everything that exists is dependent upon causes and conditions. Through such an analytical method one would gain some conceptual understanding of what emptiness is, and that leads to the direct experience of emptiness. But mahamudra teachings say that if one focuses ones mind on the mind itself and realizes the nature of the mind, then one would realize the nature

of everything else. Instead of using reasoning and the analytical method to reduce everything to emptiness as is normally done in the Mahayana approach, if one focuses ones mind on the mind itself and realizes that the nature of the mind is emptiness, then one would realize that everything else has the same nature, which is emptiness. According to mahamudra teachers the normal sutric approach of the Mahayana uses an external phenomena as objects of meditation, whereas mahamudra uses the mind itself as the object of analytical meditation. But even in relation to the mind, in mahamudra one does not analyze the mind in order to realize that the nature of the mind is emptiness. Rather, through contemplation, by allowing the mind to be in its natural state, the mind would reveal itself to have that nature. The nature of the mind is not analyzed and one does not have to have some conceptual grasp of the fact that the nature of the mind is empty. If the mind is allowed to be in its natural state and if all discursive thoughts subside, then the nature of the mind itself would be revealed as being empty of enduring essence. In a normal context, when one engages in the practice of meditation one has to use different antidotes for different obstacles. According to mahamudra, one should not become too concerned with the obstacles and also with the use of the antidotes in order to quieten the mind. One should have a general sense that all obstacles that arise in meditation can be divided into two categories. One is the obstacle of stupor or drowsiness and the other is mental agitation. With stupor, even though the mind is not disturbed by the agitation of discursive thoughts or emotional conflicts, nonetheless there is no sense of clarity in the mind. The mind has become dull and sometimes of course this gets followed by sleepiness and drowsiness. Mental agitation on the other hand is easier to detect because ones mind has fallen under the influence of discursive thoughts, distractions, emotional conflicts and so on. Instead of using different antidotes to control the mind in these situations, the mahamudra approach recommends two methods. One is relaxation and the other is a tightening up process. If the mind has become dull, then one should tighten the mind with the application of mindfulness. One should try to regenerate and refuel the sense of mindfulness of the meditation object, whatever it happens to be. If ones mind is agitated, then one should not apply too much mindfulness, but relax the mind more. If mental agitation is present during meditation, then one needs to loosen the mind, in a sense let