Particularity of Description

Diunggah oleh

Ennaid121Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Particularity of Description

Diunggah oleh

Ennaid121Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

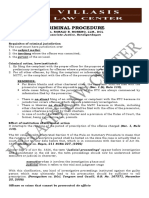

PARTICULARITY OF DESCRIPTION 1) BACHE & CO. VS. RUIZ (GR 32409, FEB.

27, 1971) FACTS: Commissioner of Internal Revenue Vera wrote a letter addressed to Judge Vivencio M. Ruiz requesting the issuance of a search warrant against Bache& Co. (Phil.), Inc. and Frederick E. Seggerman for violation of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC) and authorizing Revenue Examiner Rodolfo de Leon to make and file the application for search warrant which was attached to the letter. In the afternoon of the following day, De Leon and his witness, Arturo Logronio, went to the Court of First Instance (CFI) of Rizal. They brought with them the following papers: Veras letter-request; an application for search warrant already filled up but still unsigned by De Leon; an affidavit of Logronio subscribed before De Leon; a deposition in printed form of Logronio already accomplished and signed by him but not yet subscribed; and a search warrant already accomplished but still unsigned by Judge Ruiz. At that time Judge Ruiz was hearing a certain case; so, by means of a note, he instructed his Deputy Clerk of Court to take the depositions of De Leon and Logronio. After the session had adjourned, Judge Ruiz was informed that the depositions had already been taken. The stenographer read to him her stenographic notes; and thereafter, Judge Ruiz asked respondent Logronio to take the oath and warned him that if his deposition was found to be false and without legal basis, he could be charged for perjury The Judge signed de Leons application for search warrant and Logronios deposition. Search Warrant was then signed by the judge and accordingly issued. 3 days later (a Saturday), the BIR agents served the search warrant to the corporation and Seggerman at the offices of the corporation. ISSUE: WON the search warrant is valid.

HELD: Search warrant is invalid. RATIO: There was no personal examination conducted by the Judge of the complainant (De Leon) and his witness (Logronio). The judge did not ask either of the two any question the answer to which could possibly be the basis for determining whether or not there was probable cause against Bache & Co. and Seggerman. The participation of the judge in the proceedings which led to the issuance of the search was thus limited to listening to the stenographers readings of her notes, to a few words of warning against the commission of perjury, and to administering the oath to the complainant and his witness. This cannot be considered a personal examination. Personal examination by the judge of the complainant and his witnesses is necessary to enable him to determine the existence or non-existence of a probable cause. Next, the search warrant was issued for more than one specific offense. The search warrant was issued for at least 4 distinct offenses under the Tax Code. As ruled in Stonehill Such is the seriousness of the irregularities committed in connection with the disputed search warrants, that this Court deemed it fit to amend Section 3 of Rule 122 of the former Rules of Court that a search warrant shall not issue but upon probable cause in connection with one specific offense. Not satisfied with this qualification, the Court added thereto a paragraph, directing that no search warrant shall issue for more than one specific offense.

2) Silva VS. Presiding Judge FACTS: Sgt. Villamor, chief of the PC Narcom Detachment in Dumaguete City filed an "application for search warrant" and "Deposition of witness" against petitioner Nicomedes Silva and Martin Silva. Judge Nickarter Ontal, then the presiding judge of RTC of Dumaguete

issued Search Warrant No.1 pursuant to the said applications for violation of RA 6425 Dangerous Drugs ACT of 1972. Such warrant states that there is a probable cause to believe that Mr. Tama Silva has the possession and control of marijuana dried leaves, cigarette and joint. The warrant authorizes Sgt. Villamor to make an immediate search at any time of the room of Mr. Tama Silva at the residence of his father Comedes Silva and to open aparadors, lockers,cabinets, cartons and containers to look for said illegal drugs. In the course of the search, the officers seized money belonging to Antonieta Silva in the amount of P1,231.40. Petitioner filed a motion to quashSearch Warrant No.1 on the ground that 1) it was issued on the sole basis of mimeographed 2) the judge failed to personally examine the complainant and witness by searching questions and answers.

Examination of the complainant, record -the judge before issuing the warrant, personally examine in the form of searching questions andanswers, in writing and under oath the complainant and any witness he may produce the facts personally known to them and attach to the record their sworn statements together with their affidavits.

3) PEOPLE VS VELOSO FACTS: In May, 1923, the building located at No. 124 Calle Arzobispo, City of Manila, was used by an organization known as the Parliamentary Club. Jose Ma. Veloso was at that time a member of the House of Representative of the Philippine Legislature. He was also the manager of the club. The police of Manila had reliable information that the so-called Parliamentary Club was nothing more than a gambling house. Indeed, on May 19, 1923, J. F. Townsend, the chief of the gambling squad, had been to the club and verified this fact. As a result, on May 25, 1923, Detective Andres Geronimo of the secret service of the City of Manila, applied for, and obtained a search warrant from Judge Garduo of the municipal court. Thus provided, the police attempted to raid the Parliamentary Club a little after three in the afternoon of the date abovementioned. They found the doors to the premises closed and barred. Accordingly, one band of police including policeman Rosacker, ascended a telephone pole, so as to enter a window of the house. Other policemen, headed by Townsend, broke in the outer door. Once inside the Parliamentary Club, nearly fifty persons were apprehended by the police. One of them was the defendant Veloso. Veloso asked Townsend what he wanted, and the latter showed him the search warrant. Veloso read it and told Townsend that he was Representative Veloso and not John Doe, and that the police had no right to search the house. Townsend answered that Veloso was considered as John Doe. As Veloso's pocket was bulging, as if it contained gambling utensils, Townsend required Veloso to show him the evidence of the game.

ISSUE: Whether or Not Search Warrant No.1 is invalid. WON the officers abused their authority in seizing the money of Antonieta Silva.

HELD: Search Warrant No. 1 is invalid due to the failure of the judgeto examine the witness in the form of searching questions andanswers. The questions asked were leading as they are answerable by mere yes or no. Such questions are not sufficiently searching to establish probable cause. The questions were already mimeographed and all the witness had to do was fill in their answers on the blanks provided. Judge Ontal is guilty of grave abuse of discretion when he rejected the motion of Antonieta Silva seeking the return of her money. The officers who implemented the search warrant clearly abused their authority when they seized the money of Antonieta Silva. The warrant did not indicate the seizure of money but only for marijuana leaves, cigarettes..etc. Search Warrant No. 1 is declared null and void. *** Sec 4 Rule 126 Rules of Court

About five minutes was consumed in conversation between the policemen and the accused the policemen insisting on searching Veloso, and Veloso insisting in his refusal to submit to the search. At last the patience of the officers was exhausted. So policeman Rosacker took hold of Veloso only to meet with his resistance. Veloso bit Rosacker in the right forearm, and gave him a blow in another part of the body, which injured the policeman quite severely. Through the combined efforts of Townsend and Rosacker, Veloso was finally laid down on the floor, and long sheets of paper, of reglas de monte, cards, cardboards, and chips were taken from his pockets. All of the persons arrested were searched and then conducted to the patrol wagons. Veloso again refused to obey and shouted offensive epithets against the police department. It was necessary for the policemen to conduct him downstairs. At the door, Veloso resisted so tenaciously that three policemen were needed to place him in the patrol wagon. Issue: WON the search warrant and the arrest of Veloso was valid. HELD: Yes. RATIO: It is provided, among other things, in the Philippine Code on Criminal Procedure that a search warrant shall not issue except for probable cause and upon application supported by oath particularly describing the place to be searched and the person of thing to be seized. The name and description of the accused should be inserted in the body of the warrant and where the name is unknown there must be such a description of the person accused as will enable the officer to identify him when found. A warrant for the apprehension of a person whose true name is unknown, by the name of "John Doe" or "Richard Roe," "whose other or true name in unknown," is void, without other and further descriptions of the person to be apprehended, and such warrant will not justify the officer in acting under it. Such a warrant must, in addition,

contain the best descriptio personae possible to be obtained of the person or persons to be apprehended, and this description must be sufficient to indicate clearly the proper person or persons upon whom the warrant is to be served; and should state his personal appearance and peculiarities, give his occupation and place of residence, and any other circumstances by means of which he can be identified. In the first place, the affidavit for the search warrant and the search warrant itself described the building to be searched as "the building No. 124 Calle Arzobispo, City of Manila, Philippine Islands." This, without doubt, was a sufficient designation of the premises to be searched. As the search warrant stated that John Doe had gambling apparatus in his possession in the building occupied by him at No. 124 Calle Arzobispo, City of Manila, and as this John Doe was Jose Ma. Veloso, the manager of the club, the police could identify John Doe as Jose Ma. Veloso without difficulty.

4) PANGANDAMAN VS CASAR Facts: -On July 27, 1985, a shooting incident occurred in Pantao, Masiu, Lanao del Sur, which left at least fivepersons dead and two others wounded. What in fact transpired is still unclear. -On the following day, Atty. Mangurun Batuampar, claiming to represent the widow of one of the victims, filed a letter-complaint with the Provincial Fiscal at Marawi City, asking for a "full blast preliminary investigation" of the incident. The letter adverted to the possibility of innocent persons being implicated by the parties involved on both sides none of whom was, however, identified and promised that supporting affidavits would shortly be filed. Immediately the Provincial Fiscal addressed a "1stendorsement" to the respondent Judge, transmitting Atty. Batuampar's letter and requesting that " all cases that may be filed relative (to the incident) that happened in the afternoon of July 27, 1985 ," be forwarded to his office, which " has first taken cognizance of said cases."

-No case relative to the incident was, however, presented to the respondent Judge until Saturday, August10, 1985, when a criminal complaint for multiple murder was filed before him by P.C. Sgt. Jose L. Laruan, which was docketed as Case No. 1748. On that same day, the respondent Judge " examined personally all(three) witnesses (brought by the sergeant) under oath thru (his) closed and direct supervision ,"reducing to writing the questions to the witnesses and the latter's answers. Thereafter the Judge " approved the complaint and issued the corresponding warrant of arrest " against the fourteen (14)petitioners (who were named by the witnesses) and fifty (50) John Does. -An "ex-parte" motion for reconsideration was filed on August 14, 1985 by Atty. Batuampar (joined by Atty.Pama L. Muti), seeking recall of the warrant of arrest and subsequent holding of a "thorough investigation on the ground that the Judge's initial investigation had been "hasty and manifestly haphazard" with "no searching questions" having been propounded. The respondent Judge denied the motion for lack of basis. -The petitioners contend: -that the Judge in the case at bar failed to conduct the investigation in accordance with the procedure prescribed in Section 3, Rule 112 of the Rules of Court;- that failure constituted a denial to petitioners of due process which nullified the proceedings leading to the issuance of the warrant for the petitioners' arrest; - that August 10, 1985 was a Saturday during which " Municipal Trial Courts are open from 8:00 a.m.to 1:00 p.m. only ..." and "... it would hardly have been possible for respondent Judge to determine the existence of probable cause against sixty- four (64) persons whose participations were of varying nature and degree in a matter of hours and issue the warrant of arrest in the same day"; -that there was undue haste and an omission to ask searching questions by the Judge who relied" mainly on the supporting affidavits which were obviously prepared already when

presented to him by an enlisted PC personnel as investigator."; - that the respondent Judge conducted the preliminary investigation of the charges " ... in total disregard of the Provincial Fiscal ..." who, as said respondent well knew, had already taken cognizance of the matter twelve (12) days earlier and was poised to conduct his own investigation of the same; and- that issuance of a warrant of arrest against fifty (50) "John Does" transgressed the Constitutional provision requiring that such warrants should particularly describe the persons or things to be seized. Issue: WON the warrant of arrest was null and void. More specifically stated, WON completion of the procedure laid down in Section 3 of Rule 112 a condition sine qua non for the issuance of a warrant of arrest. Ruling: The warrant complained of is upheld and declared valid insofar as it orders the arrest of the petitioners. Said warrant is voided to the extent that it is issued against fifty (50) "John Does." The respondent Judge is directed to forward to the Provincial Fiscal of Lanao del Sur the record of the preliminary investigation of the complaint in Criminal Case No. 1728 of his court for further appropriate action. RD: Sec 3 of Rule 112 of the 1985 Rules on Criminal Procedure provides the procedure in conducting a pre-investigation of any crime cognizable in the RTCs. Although not specifically declared the said provision actually mandates two phases. The first phase consists of an ex-parte inquiry into the sufficiency of the complaint and the affidavits and other documents offered in support thereof. And it ends with the determination by the Judge either:

(1) that there is no ground to continue with the inquiry, in which case he dismisses the complaint and transmits the order of dismissal, together with the records of the case, to the provincial fiscal; or

(2) That the complaint and the supporting documents show sufficient cause to continue with the inquiry and this ushers in the second phase. This second phase is designed to give the respondent notice of the complaint, access to the complainant's evidence and an opportunity to submit counter-affidavits and supporting documents. At this stage also, the Judge may conduct a hearing and propound to the parties and their witnesses questions on matters that, in his view, need to be clarified. The second phase concludes with the Judge rendering his resolution, either for dismissal of the complaint or holding the respondent for trial, which shall be transmitted, together with the record, to the provincial fiscal for appropriate action. There is no requirement that the entire procedure for preliminary investigation must be completed before a warrant of arrest may be issued. The present Section 6 of the same Rule 112 clearly authorizes the municipal trial court to order the respondent's arrest:Sec. 6. When warrant of arrest may issue.- xxx xxx xxx (b) By the Municipal Trial Court. If the municipal trial judge conducting the preliminary investigation is satisfied after an examination in writing and under oath of the complainant and his witnesses in the form of searching question and answers, that a probable cause exists and that there is a necessity of placing the respondent under immediate custody in order not to frustrate the ends of justice, he shag issue a warrant of arrest. The argument, therefore, must be rejected that the respondent Judge acted with grave abuse of discretion in issuing the warrant of arrest against petitioners without first completing the preliminary investigation in accordance with the prescribed procedure. The rule is and has always been that such issuance need only await a finding of probable cause, not the completion of the entire procedure of preliminary investigation.

A petition for certiorari has been filed to invalidate the order of Judge Casanova which quashed search warrant issued by Judge Bacalla and declared inadmissible for any purpose the items seized under the warrant. >An application for a search warrant was made by S/Insp Brillantes against Mr. Azfar Hussain who had allegedly in his possession firearms and explosives at Abigail Variety Store, Apt 1207 Area F. Bagon Buhay Avenue, Sarang Palay, San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan. The following day Search Warrant No. 1068 was issued but was served not at Abigail Variety Store but at Apt. No. 1, immediately adjacent to Abigail Variety Store resulting in the arrest of 4 Pakistani nationals and the seizure of a number of different explosives and firearms. ISSUE: WON a search warrant was validly issued as regard the apartment in which private respondents were then actually residing, or more explicitly, WON that particular apartment had been specifically described in the warrant. HELD: The ambiguity lies outside the instrument, arising from the absence of a meeting of minds as to the place to be searched between the applicants for the warrant and the Judge issuing the same; and what was done was to substitute for the place that the Judge had written down in the warrant, the premises that the executing officers had in their mind. This should not have been done. It is neither fair nor licit to allow police officers to search a place different from that stated in the warrant on the claim that the place actually searched although not that specified in the warrant is exactly what they had in view when they applied for the warrant and had demarcated in their supporting evidence. What is material in determining the validity of a search is the place stated in the warrant itself, not what the applicants had in their thoughts, or had represented in the proofs they submitted to the court issuing the warrant. The place to be searched, as set out in the warrant, cannot be amplified or modified by the officers' own personal knowledge of the premises, or the evidence they adduced in

5) PEOPLE VS CA FACTS:

support of their application for the warrant. Such a change is proscribed by the Constitution which requires inter alia the search warrant to particularly describe the place to be searched as well as the persons or things to be seized. It would concede to police officers the power of choosing the place to be searched, even if it not be that delineated in the warrant. It would open wide the door to abuse of the search process, and grant to officers executing a search warrant that discretion which the Constitution has precisely removed from them. The particularization of the description of the place to be searched may properly be done only by the Judge, and only in the warrant itself; it cannot be left to the discretion of the police officers conducting the search.

premises was evident in the issuance of the two warrant. As to the issue that the items seized were real properties, the court applied the principle in the case of Davao Sawmill Co. v. Castillo, ruling that machinery which is movable by nature becomes immobilized when placed by the owner of the tenement, property or plant, but not so when placed by a tenant, usufructuary, or any other person having only a temporary right, unless such person acted as the agent of the owner. In the case at bar, petitioners did not claim to be the owners of the land and/or building on which the machineries were placed. This being the case, the machineries in question, while in fact bolted to the ground remain movable property susceptible to seizure under a search warrant. However, the Court declared the two warrants null and void. Probable cause for a search is defined as such facts and circumstances which would lead a reasonably discreet and prudent man to believe that an offense has been committed and that the objects sought in connection with the offense are in the place sought to be searched. The Court ruled that the affidavits submitted for the application of the warrant did not satisfy the requirement of probable cause, the statements of the witnesses having been mere generalizations. Furthermore, jurisprudence tells of the prohibition on the issuance of general warrants. (Stanford vs. State of Texas). The description and enumeration in the warrant of the items to be searched and seized did not indicate with specification the subversive nature of the said items.

6) BURGOS VS CHIEF OF STAFF FACTS: Two warrants were issued against petitioners for the search on the premises of Metropolitan Mail and We Forum newspapers and the seizure of items alleged to have been used in subversive activities. Petitioners prayed that a writ of preliminary mandatory and prohibitory injunction be issued for the return of the seized articles, and that respondents be enjoined from using the articles thus seized as evidence against petitioner. Petitioners questioned the warrants for the lack of probable cause and that the two warrants issued indicated only one and the same address. In addition, the items seized subject to the warrant were real properties. ISSUE: Whether or not the two warrants were valid to justify seizure of the items. HELD: The defect in the indication of the same address in the two warrants was held by the court as a typographical error and immaterial in view of the correct determination of the place sought to be searched set forth in the application. The purpose and intent to search two distinct

7) FRANK UY VS BIR FACTS: In Sept 1993, Rodrigo Abos, a former employee of UPC reported to the BIR that Uy Chin Ho aka Frank Uy, manager of UPC, was selling thousands of cartons of canned cartons without

issuing a report. This is a violation of Sec 253 & 263 of the Internal Revenue Code. In Oct 1993, the BIR requested before RTC Cebu to issue a search warrant. Judge Gozo-Dadole issued a warrant on the same day. A second warrant was issued which contains the same substance but has only one page, the same was dated Oct st 1 2003. These warrants were issued for the alleged violation by Uy of Sec 253. A third warrant was issued on the same day for the alleged violation of Uy of Sec 238 in relation to sec 263. On the strength of these warrants, agents of the BIR, accompanied by members of the PNP, on 2 Oct 1993, searched the premises of the UPC. They seized, among other things, the records and documents of UPC. A return of said search was duly made by Labaria with the RTC of Cebu. UPC filed a motion to quash the warrants which was denied by the RTC. They appealed before the CA via certiorari. The CA dismissed the appeal for a certiorari is not the proper remedy. ISSUE: Whether or not there was a valid search warrant issued. HELD: The SC ruled in favor of UPC and Uy in a way for it ordered the return of the seized items but sustained the validity of the warrant. The SC ruled that the search warrant issued has not met some basic requisites of validity. A search warrant must conform strictly to the requirements of the foregoing constitutional and statutory provisions. These requirements, in outline form, are: (1) the warrant must be issued upon probable cause; (2) the probable cause must be determined by the judge himself and not by the applicant or any other person; (3) in the determination of probable cause, the judge must examine, under oath or affirmation, the complainant and such witnesses as the latter may produce; and

(4) the warrant issued must particularly describe the place to be searched and persons or things to be seized. The SC noted that there has been inconsistencies in the description of the place to be searched as indicated in the said warrants. Also the thing to be seized was not clearly defined by the judge. He used generic itineraries. The warrants were also inconsistent as to who should be searched. One warrant was directed only against Uy and the other was against Uy and UPC. The SC however noted that the inconsistencies wered cured by the issuance of the latter warrant as it has revoked the two others.

unlawful and that the personalities seized during the illegal search should be returned to the petitioner. The respondents, in defense, concede that the search warrants were null and void but the arrests were not. ISSUE: WON The Search warrants were null and void but the arrests were not HELD: "Any evidence obtained in violation of this . . . section shall be inadmissible for any purpose in any proceeding (Sec. 4[2]). This constitutional mandate expressly adopting the exclusionary rule has proved by historical experience to be the only practical means of enforcing the constitutional injunction against unreasonable searches and seizures by outlawing all evidence illegally seized and thereby removing the incentive on the part of state and police officers to disregard such basic rights. What the plain language of the Constitution mandates is beyond the power of the courts to change or modify. All the articles thus seized fall under the exclusionary rule totally and unqualifiedly and cannot be used against any of the three petitioners.

EXLUSIONARY RULE 1) BALIHOG VS FERNANDEZ

2) NOLASCO VS PAO 3) NASIAD VS CA FACTS: The case at bar is for the motion for partial reconsideration of both petitioners and respondents of the SCs decision that the questioned search warrant by petitioners is null and void, that respondents are enjoined from introducing evidence using such search warrant, but such personalities obtained would still be retained, without prejudice to petitioner Aguilar-Roque. Respondents contend that the search warrant is valid and that it should be considered in the context of the crime of rebellion, where the warrant was based. Petitioners on the other hand, on the part of petitioner Aguilar-Roque, contend that a lawful search would be justified only by a lawful arrest. And since there was illegal arrest of Aguilar-Roque, the search was FACTS:

RULING: One of the exceptions to the general rule requiring a search warrant is a search incident to a lawful arrest. Thus, Section 12 of Rule 126 of the 1985 Rules on Criminal Procedure provides: Section 12. Search incident to a lawful arrest. A person lawfully arrested may be searched for dangerous weapons or anything which may be used as proof of the commission of an offense, without a search warrant. Meanwhile, Rule 113, Sec. 5 (a) provides: A peace officer or a private person may, without a warrant, arrest a person when, in his presence, the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense. Accused was caught in flagrante, since he was carrying marijuana at the time of his arrest. This case therefore falls squarely within the exception. The warrantless search was incident to a lawful arrest and is consequently valid. ALLOWABLE WARRANTLESS ARREST 1) PEOPLE VS SALAZAR Although the trial court's decision did not mention it, the transcript of stenographic notes reveals that there was an informer who pointed to the accused-appellant as carrying marijuana. Faced with such on-the-spot information, the police officers had to act quickly. There was not enough time to secure a search warrant.

2) PEOPLE VS TANGLIBEN FACTS: Patrolmen Quevedo and. Punzalan were conducting surveillance mission at the Victory Liner Terminal compound located at Barangay San Nicolas, San Fernando, Pampanga. It was around 9:30 in the evening that said Patrolmen noticed Medel Tangliben carrying a traveling bag who was acting suspiciously. They confronted Tangliben and requested to open the red traveling bag but the latter refused, only to accede later on when the patrolmen identified themselves. Marijuana leaves wrapped in a plastic wrapper and weighing one kilo, more or less, were found inside the bag. ISSUE: WON the marijuana allegedly seized from the accused was a product of an unlawful search without a warrant and is therefore inadmissible in evidence.

3) PEOPLE VS EVARISTO FACTS: Peace officers while patrol, heard burst of gunfire and proceeded to investigate in the house of appellant where they were given permission to enter accidentally discovering the firearms in the latters possession. Accusedappellant found guilty of illegal possession of firearms contends that the seizure of the evidence is inadmissible because it was not authorized by a valid warrant.

ISSUE: Whether or not the evidence obtained without warrant in an accidental discovery of the evidence is admissible.

HELD: Yes, the firearms seized was valid and lawful for being incidental to a lawful arrest. An offense was committed in the presence or within the view of an officer, within the meaning of the rule authorizing an arrest without a warrant.

4) PEOPLE VS BALINGAN

surveillance activities on the suspected syndicate, of which appellant was touted to be a member. Aside from this, they were also certain as to the expected date and time of arrival of the accused from China via Hong Kong. But such knowledge was insufficient to enable them to fulfill the requirements for the issuance of a search warrant. Still and all, the important thing is that there was probable cause to conduct the warrantless search, which must still be present in the case. Exception to the issuance of search warrant:

5) PEOPLE VS LO HO WING FACTS: Peter Lo , together with co-accused Lim Cheng Huat alias Antonio Lim and Reynaldo Tia, were charged with a violation of the Dangerous Drugs Act, for the transport of metamphetamine hydrochloride, otherwise known as "shabu". The drug was contained in tea bags inside tin cans which were placed inside their luggages. Upon arrival from Hong Kong, they boarded the taxis at the airport which were apprehended by CIS operatives. Their luggages were subsequently searched where the tea bags were opened and found to contain shabu. Only Lo and Lim were convicted. Tia was discharged as a state witness, who turned out to be a deep penetration agent" of the CIS in its mission to bust the drug syndicate ISSUE: WON the search and seizure was legal. HELD: YES that search and seizure must be supported by a valid warrant is not an absolute rule. One of the exceptions thereto is a search of a moving vehicle. The circumstance of the case clearly show that the search in question was made as regards a moving vehicle. Therefore, a valid warrant was not necessary to effect the search on appellant and his coaccused. It was firmly established from the factual findings of the court that the authorities had reasonable ground to believe that appellant would attempt to bring in contraband and transport within the country. The belief was based on intelligence reports gathered from

1) search incidental to a lawful arrest; 2) search of moving vehicle; 3) seizure of evidence in plain view.

6) DE GARCIA VS LOCSIN FACTS: Mariano G. Almeda, an agent of the Anti-Usuary Board, obtained from the justice of the peace of Tarlac, a search warrant commanding any officer of the law to search the person, house or store of the petitioner at Victoria, Tarlac, for certain books, lists, chits, receipts, documents and other papers relating to her activities as usurer. The search warrant was issued upon an affidavit given by the said Almeda. On the same date, the said Mariano G. Almeda, accompanied by a captain of the Philippine Constabulary, went to the office of the petitioner in Victoria, Tarlac and, after showing the search warrant to the petitioners bookkeeper, Alfredo Salas, and, without the presence of the petitioner who was ill and confined at the time, proceeded with the execution thereof The papers and documents seized were kept for a considerable length of time by the Anti-Usury Board and thereafter were turned over by it to the respondent fiscal who subsequently filed six separate criminal cases against the herein petitioner for violation of the Anti-Usury Law. ISSUE: The legality of the search warrant was challenged by counsel for the petitioner in the six criminal cases and the devolution of the documents demanded. The respondent Judge

denied the petitioners motion for the reason that though the search warrant was illegal, there was a waiver on the part of the petitioner. HELD: Freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures is declared a popular right and for a search warrant to be valid, (1) it must be issued upon probable cause; (2) the probable cause must be determined by the judge himself and not by the applicant or any other person; (3) in the determination of probable cause, the judge must examine, under oath or affirmation, the complainant and such witnesses as the latter may produce; and (4) the warrant issued must particularly describe the place to be searched and persons or things to be seized. In the instant case the existence of probable cause was determined not by the judge himself but by the applicant. All that the judge did was to accept as true the affidavit made by agent Almeda. He did not decide for himself. It does not appear that he examined the applicant and his witnesses, if any. Even accepting the description of the properties to be seized to be sufficient and on the assumption that the receipt issued is sufficiently detailed within the meaning of the law, the properties seized were not delivered to the court which issued the warrant, as required by law. Instead, they were turned over to the resp. provincial fiscal & used by him in building up cases against petitioner. Considering that at the time the warrant was issued, there was no case pending against the petitioner, the averment that the warrant was issued primarily for exploration purposes is not without basis.

Respondent Ricardo Santos is the owner of a Mercury automobile, model 1957. It was brought into this country without the payment of customs duty and taxes, its owner Donald James Hatch being tax-exempt. It was from him that respondent Santos acquired said car. He paid P311.00 for customs duty and taxes. Land Transportation Commission reported that such automobile was a "hot car." By virtue thereof, petitioner Pacis, ascertained that although the amount of P311.00 was already paid for customs duty, the amount collectible on said car should be P2,500.00, more or less. Pacis instituted seizure proceedings and issued a warrant of seizure and detention. Ricardo Santos filed a criminal complaint for usurpation of judicial functions with the City Fiscal of Manila handled by Pamaran. ISSUE: WON the Collector of Customs has the authority to issue the warrant of seizure

HELD: Yes, as Acting Collector of Customs for the Port of Manila, he had the requisite authority for the issuance of the contested warrant of seizure and detention for the automobile owned by respondent Ricardo Santos. It is to be admitted that the constitutional right to be free from unreasonable search and seizure must not be eroded or emasculated. The right to privacy so highly valued in civilized society must not be diluted. Only upon compliance then with the proper requisites mandated by law should one's possessions be subject to seizure. That much is clear. Under the 1935 Constitution the intervention of a judge was well-nigh indispensable. So it was under the Philippine Bill of 1902 and the Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916. Even then, however, as shown by the leading case of Uy Kheytin v. Villareal, a 1920 decision, it was the accepted principle following the landmark case of Boyd v. United States that the seizure of goods concealed to avoid the duties on them is not embraced within the prohibition of this constitutional guarantee. More to the point. In a

7) PEOPLE VS AGBOT

8) PEOPLE VS PAMARAN FACTS: Pacis is the Acting Collector of Customs for the Port of Manila. The case is prohibition proceeding against Assistant City Fiscal of Manila, Manuel R. Pamaran.

recent decision of this Court, Papa v. Mago, where the seizure of alleged smuggled goods was effected by a police officer without a search warrant, this Court, through Justice Zaldivar, stated: "Petitioner Martin Alagao and his companion policemen had authority to effect the seizure without any search warrant issued by a component court. The Tariff and Customs Code does not require said warrant in the instant case. The Code authorizes persons having police authority under Section 2203 of the Tariff and Customs Code to enter, pass through or search any land, inclosure, warehouse, store or building, not being a dwelling house; and also to inspect, search and examine any vessel or aircraft and any trunk, package, box or envelope or any person on board, or stop and search and examine any vehicle, beast or person suspected of holding or conveying any dutiable or prohibited article introduced into the Philippines contrary to law, without mentioning the need of a search warrant in said cases. But in the search of a dwelling house, the Code provides that said 'dwelling house may be entered and searched only upon warrant issued by a judge or justice of the peace . . . .' It is our considered view, therefore, that except in the case of the search of a dwelling house, persons exercising police authority under the customs law may effect search and seizure without a search warrant in the enforcement of customs laws." The plenitude of the competence vested in customs officials is thus undeniable. No such constitutional question then can possibly arise. So much is implicit from the very language of Section 2205 of the Tariff and Customs Code. It speaks for itself. It is not susceptible of any misinterpretation. The power of petitioner is thus manifest. It being undeniable then that the sole basis for an alleged criminal act performed by him was the performance of a duty according to law, there is not the slightest justification for respondent Assistant City Fiscal to continue with the preliminary investigation after his attention was duly called to the plain and explicit legal provision that did not suffer at all from any constitutional infirmity. The remedy of prohibition lies.

What was done by petitioner was strictly in accordance with settled principles of law. No doubt need be entertained then as to the validity of the issuance of the warrant of seizure and detention. His liability for any alleged usurpation of judicial function is non-existent. Such imputation was definitely unfounded. Even if however the matter were less clear, the claim that the search and seizure clause was in effect nullified is hardly impressed with merit. Considering that what is involved is an alleged evasion of the payment of customs duties.

Whether or not the warantless arrest and search was valid. Ruling: An arrest without a warrant may be effected by a peace officer or private person, among others, when in his presence the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense; or when an offense has in fact just been committed, and he has personal knowledge of the facts indicating that the person arrested has committed it. Contrary to the argument of the Solicitor General that when the two policemen approached the petitioner, he was actually committing or had just committed the offense of illegal possession of firearms and ammunitions in the presence of the police officers and consequently the search and seizure of the contraband was incidental to the lawful arrest in accordance with Section 12, Rule 126 of the 1985 Rules on Criminal Procedure; At the time the peace officers in this case identified themselves and apprehended the petitioner as he attempted to flee they did not know that he had committed, or was actually committing the offense of illegal possession of firearms and ammunitions. They just suspected that he was hiding something in the buri bag. They did not know what its contents were. The said circumstances did not justify an arrest without a warrant. 2) MALACAT VS CA

STOP AND FRISK 1) POSADAS VS CA Facts: While Pat. Ungab and Umpar were conducting a surveillance along Magallanes Street, Davao City, they spotted petitioner carrying a "buri" bag and they noticed him to be acting suspiciously.They approached the petitioner and identified themselves as members of the INP. Petitioner attempted to flee but his attempt to get away was thwarted by the two notwithstanding his resistance. They then checked the "buri" bag of the petitioner where they found one (1) caliber .38 revolver, two (2) rounds of live ammunition for a .38 caliber gun 2 a smoke (tear gas) grenade, 3 and two (2) live ammunitions for a .22 caliber gun. 4 the petitioner was asked to show the necessary license or authority to possess the firearms and ammunitions but failed to do so. Issue:

3) PEOPLE VS DE GARCIA FACTS: The incidents involved in this case took place at the height of the coup d''etat staged in December, 1989. Accused-appellant Rolan-do de Gracia was charged in two separate informations for illegal possession of ammunition and explosives in furtherance of rebel-lion, and for attempted homicide. Appellant was convicted for illegal possession of firearms in furtherance of rebellion, but was acquitted of attempted homicide. Surveillance was undertaken by the military along EDSA because of intelligence reports about a coup. Members of the team were engaged by rebels in gunfire killing one

member of the team. A searching team raided the Eurocar Sales Office. They were able to find and confiscate six cartons of M-16 ammunition, five bundles of C-4 dynamites, M-shells of different calibers, and "molotov" bombs inside one of the rooms belonging to a certain Col. Matillano. De Gracia was seen inside the office of Col. Matillano, holding a C-4 and suspiciously peeping through a door. The team arrested appellant. They were then made to sign an inventory, written in Tagalog, of the explo-sives and ammunition confiscated by the raiding team. No search warrant was secured by the raiding team. Accused was found guilty of illegal possession of firearms. ISSUE: That judgment of conviction is now challenged before us in this appeal. Issue: Whether or not there was a valid search and seizure in this case. RULING: YES It is admitted that the military operatives who raided the Euro-car Sales Office were not armed with a search warrant at that time. The raid was actually precipitated by intelligence reports that said office was being used as headquarters by the RAM. Prior to the raid, there was a surveillance conducted on the premises wherein the surveillance team was fired at by a group of men coming from the Eurocar building. When the military opera-tives raided the place, the occupants thereof refused to open the door despite requests for them to do so, thereby compelling the former to break into the office. The Eurocar Sales Office is obviously not a gun store and it is definitely not an armory or arsenal which are the usual depositories for explosives and ammunition. It is primarily and solely engaged in the sale of automobiles. The presence of an unusual quantity of highpowered firearms and explosives could not be justifiably or even color-ably explained. In addition, there was general chaos and disorder at that time because of simultaneous and intense firing within the vicinity of the office and in the nearby Camp Aguinaldo which was under attack by rebel forces. The courts in the surrounding areas were obviously closed and,

for that matter, the building and houses therein were deserted. Under the foregoing circumstances, it is our considered opinion that the instant case falls under one of the exceptions to the prohibition against a warrantless search. In the first place, the military operatives, taking into account the facts obtaining in this case, had reasonable ground to believe that a crime was being committed. There was consequently more than sufficient probable cause to warrant their action. Furthermore, under the situation then prevailing, the raiding team had no opportunity to apply for and secure a search warrant from the courts. Under such urgency and exigency of the moment, a search warrant could law-fully be dispensed with.

4) PEOPLE VS CHE CHUN TING FACTS: Accused-appellant was charged and convicted for dispatching in transit and having in his possession large amounts of shabu. He contends that the shabu is inadmissible in evidence as it was seized without a valid search warrant.

ISSUE: WON the search and seizure was valid HELD: The lawful arrest being the sole justification for the validity of the warrantless search under the exception, the same must be limited to and circumscribed by the subject, time and place of the arrest. As to subject, the warrantless search is sanctioned only with respect to the person of the suspect, and things that may be seized from him are limited to dangerous weapons or anything which may be used as proof of the commission of the offense. With respect to the time and place of the warrantless search, it must be contemporaneous with the lawful arrest. Stated otherwise, to be valid, the search must have been conducted at about the time of the arrest or immediately thereafter and only at the place where the suspect was arrested, or the

premises or surroundings under his immediate control. It must be stressed that the purposes of the exception are only to protect the arresting officer against physical harm from the person being arrested who might be armed with a concealed weapon, and also to prevent the person arrested from destroying the evidence within his reach. The exception therefore should not be strained beyond what is needed in order to serve its purposes. As a consequence of the illegal search, the things seized on the occasion thereof are inadmissible in evidence under the exclusionary rule. They are regarded as having been obtained from a polluted source, the fruit of a poisonous tree. However, objects and properties the possession of which is prohibited by law cannot be returned to their owners notwithstanding the illegality of their seizure. Thus, the shabu seized by the NARCOM operatives, which cannot legally be possessed by the accused under the law, can and must be retained by the government to be disposed of in accordance with law.

Padilla claimed papers of guns were at home. His arrest for hit and run incident modified to include grounds of Illegal Possession of firearms. He had no papers. On Dec. 3, 1994, Padilla was found guilty of Illegal Possession of Firearms under PD 1866 by the RTC of Angeles City. He was convicted and sentenced to an indeterminate penalty from 17 years. 4 months, 1 day of reclusion temporal as minimum to 21 years of reclusion perpetua as maximum. The Court of Appeals confirmed decision and cancelled bailbond. RTC of Angeles City was directed to issue order of arrest. Motion for reconsideration was denied by Court of Appeals. Padilla filed lots of other petitions and all of a sudden, the Solicitor General made a complete turnaround and filed Manifestation in Lieu of Comment praying for acquittal (nabayaran siguro). ISSUE: 1. WARRANTLESS ARREST: WON his was illegal and consequently, the firearms and ammunitions taken in the course thereof are inadmissible in evidence under the exclusionary rule No. Anent the first defense, petitioner questions the legality of his arrest. There is no dispute that no warrant was issued for the arrest of petitioner, but that per se did not make his apprehension at the Abacan Bridge illegal. Warrantless arrests are sanctioned in Sec. 5, Rule 113 of the Revised Rules on Criminal Procedurea peace officer or a private person may, without a warrant, arrest a person (a) when in his presence the person to be arrested has committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an offense. When caught in flagrante delicto with possession of an unlicensed firearm and ammo, petitioners warrantless arrest was proper since he was actually committing another offence in the presence of all those officers. There was no supervening event or a considerable lapse of time between the hit and run and the actual apprehension. Because arrest was legal, the pieces of evidence are admissible. Instances when warrantless search and seizure of property is valid:

5) PADILLA VS CA FACTS: Padilla figured in a hit and run accident in Oct 26, 1992. He was later on apprehended with the help pf a civilian witness. Upon arrest following high powered firearms were found in his possession: 1. ammunition 2. ammo 3. .357 caliber revolver with 6 live M-16 Baby Armalite magazine with .380 pietro beretta with 8 ammo

4. 6 live double action ammo of .38 caliber revolver

? Seizure of evidence in plain view, elements of which are (a) prior valid intrusion based on valid warrantless arrest in which police are legally present in pursuit of official duties, (b) evidence inadvertedly discovered by police who had the right to be there, (c) evidence immediately apparent, and (d) plain view justified mere seizure of evidence without further search (People v. Evaristo: objects whose possession are prohibited by law inadvertedly found in plain view are subject to seizure even without a warrant) ?Search of moving vehicle ? Warrantless search incidental to lawful arrest recognized under section 12, Rule 126 of Rules of Court and by prevailing jurisprudence where the test of incidental search (not excluded by exclusionary rule) is that item to be searched must be within arrestees custody or area of immediate control and search contemporaneous with arrest. Petitioner would nonetheless insist on the illegality of his arrest by arguing that the policemen who actually arrested him were not at the scene of the hit and run. The court begs to disagree. It is a reality that curbing lawlessness gains more success when law enforcers function in collaboration with private citizens. Furthermore, in accordance with settled jurisprudence, any objection, defect or irregularity attending an arrest must be made before the accused enters his plea.

approached Espano, identified themselves as policemen, and frisked him. The search yielded two plastic cellophane tea bags of marijuana . When asked if he had more marijuana, he replied that there was more in his house. The policemen went to his residence where they found ten more cellophane tea bags of marijuana. Espano was brought to the police headquarters where he was charged with possession of prohibited drugs. On 24 July 1991, Espano posted bail and the trial court issued his order of release on 29 July 1991. On 14 August 1992, the trial court rendered a decision, convicting Espano of the crime charged. Espano appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals. The appellate court, however, on 15 January 1995 affirmed the decision of the trial court in toto. Espano filed a petition for review with the Supreme Court. ISSUE: Whether the search of Espanos home after his arrest does not violate against his right against unreasonable search and seizure. HELD: Espanos arrest falls squarely under Rule 113 Section 5(a) of the Rules of Court. He was caught in flagranti as a result of a buy-bust operation conducted by police officers on the basis of information received regarding the illegal trade of drugs within the area of Zamora and Pandacan Streets, Manila. The police officer saw Espano handing over something to an alleged buyer. After the buyer left, they searched him and discovered two cellophanes of marijuana. His arrest was, therefore, lawful and the two cellophane bags of marijuana seized were admissible in evidence, being the fruits of the crime. As for the 10 cellophane bags of marijuana found at Espanos residence, however, the same inadmissible in evidence. The articles seized from Espano during his arrest were valid under the doctrine of search made incidental to a lawful arrest. The warrantless search made in his house, however, which yielded ten cellophane bags of marijuana became unlawful since the police officers were not armed with a search warrant at the time. Moreover, it was beyond the reach and control of Espano. The right of the people to be secure

6) ESPANO VS CA FACTS On 14 July 1991, at about 12:30 a.m., Pat. Romeo Pagilagan and other police officers, namely, Pat. Wilfredo Aquilino, Simplicio Rivera, and Erlindo Lumboy of the Western Police District (WPD), Narcotics Division went to Zamora and Pandacan Streets, Manila to confirm reports of drug pushing in the area. They saw Rodolfo Espano selling something to another person. After the alleged buyer left, they

in their persons, houses, papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures of whatever nature and for any purposes shall be inviolable, and no search warrant or warrant of arrest shall issue except upon probable cause to be determined personally by the judge after examination under oath or affirmation of the complainant and the witnesses he may produce, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized. An exception to the said rule is a warrantless search incidental to a lawful arrest for dangerous weapons or anything which may be used as proof of the commission of an offense. It may extend beyond the person of the one arrested to include the premises or surroundings under his immediate control. Herein, the ten cellophane bags of marijuana seized at petitioners house after his arrest at Pandacan and Zamora Streets do not fall under the said exceptions.

October 1965, the Commission and the Navy filed a motion for reconsideration of the order issuing the preliminary writ Judge Arca denied the said motion for reconsideration. The Commission and the Navy filed a petition for certiorari and prohibition with preliminary injunction to restrain Judge Arca from enforcing his order dated 18 October 1965, and the writ of preliminary mandatory injunction there under issued. ISSUE: WON a police officer can search without warrant HELD: YES. Search and seizure without search warrant of vessels and air crafts for violations of the customs laws have been the traditional exception to the constitutional requirement of a search warrant, because the vessel can be quickly moved out of the locality or jurisdiction in which the search warrant must be sought before such warrant could be secured; hence it is not practicable to require a search warrant before such search or seizure can be constitutionally effected. The same exception should apply to seizures of fishing vessels breaching our fishery laws. They are usually equipped with powerful motors that enable them to elude pursuing ships of the Philippine Navy or Coast Guard. Under our Rules of Court, a police officer or a private individual may, without a warrant, arrest a person (a) who has committed, is actually committing or is about to commit an offense in his presence; (b) who is reasonably believed to have committed an offense which has been actually committed; or (c) who is a prisoner who has escaped from confinement while serving a final judgment or from temporary detention during the pendency of his case or while being transferred from one confinement to another. In the case at bar, the members of the crew of the two vessels were caught in flagrante illegally fishing with dynamite and without the requisite license. Thus their apprehension without a warrant of arrest while committing a crime is lawful. Consequently, the seizure of the vessel, its equipment and dynamites therein was equally valid as an incident to a lawful arrest. In the case

7) ROLDAN JR VS ARCA FACTS: Respondent company filed a case against Roldan, Jr. for the recovery of fishing vessel Tony Lex VI which had been seized and impounded by petitioner Fisheries Commissioner through the Philippine Navy. The CFI Manila granted it, thus respondent company took Possession of the vessel Tony Lex VI. Petitioner requested the Philippine Navy to apprehend vessels Tony Lex VI and Tony Lex III, also respectively called Srta. Winnie and Srta. Agnes, for alleged violations of some provisions of the Fisheries Act. On August 5 or 6, 1965, the two fishing boats were actually seized for illegal fishing with dynamite. The Fiscal filed an ex parte motion to hold the boats in custody as instruments and therefore evidence of the crime, and cabled the Fisheries Commissioner to detain the vessels. On October 2 and 4, likewise, the CFI of Palawan ordered the Philippine Navy to take the boats in custody. Judge Francisco Arca issued an order granting the issuance of the writ of preliminary mandatory injunction and issued the preliminary writ upon the filing by the company of a bond of P5,000.00 for the release of the two vessels. On 19

at bar, the members of the crew of the two vessels were caught in flagrante illegally fishing with dynamite and without the requisite license. Thus their apprehension without a warrant of arrest while committing a crime is lawful. Consequently, the seizure of the vessel, its equipment and dynamites therein was equally valid as an incident to a lawful arrest. 8) ANAIG VS COMELEC

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Particularity of DescriptionDokumen16 halamanParticularity of DescriptionEnnaid121Belum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Revised Ortega Lecture Notes On Criminal Law 2.1Dokumen83 halamanRevised Ortega Lecture Notes On Criminal Law 2.1Hazel Abagat-DazaBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Particularity of DescriptionDokumen2 halamanParticularity of DescriptionEnnaid121Belum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- UST GN 2011 - Legal and Judicial Ethics Proper, Index, BiblioDokumen280 halamanUST GN 2011 - Legal and Judicial Ethics Proper, Index, BiblioGhost100% (2)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- UST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDokumen88 halamanUST Golden Notes 2011 - Persons and Family RelationsDaley Catugda88% (8)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- UST Golden Notes 2011 ObliCon PDFDokumen56 halamanUST Golden Notes 2011 ObliCon PDFEnnaid121100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Pre Trial Motion PracticeDokumen40 halamanPre Trial Motion Practicemalo5680% (5)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Justice Moreno - Crimpro Bar LectureDokumen32 halamanJustice Moreno - Crimpro Bar LectureBar BeksBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- ARTICLE 33 and 36 MANOLO P. SAMSON, Petitioners, v. CATERPILLAR, INC., Respondent. Decision Austria-Martinez, J.Dokumen20 halamanARTICLE 33 and 36 MANOLO P. SAMSON, Petitioners, v. CATERPILLAR, INC., Respondent. Decision Austria-Martinez, J.tink echivereBelum ada peringkat

- Motion to Quash: Grounds, Exceptions, and EffectsDokumen21 halamanMotion to Quash: Grounds, Exceptions, and EffectsmjpjoreBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Motion To Reduce BailDokumen2 halamanMotion To Reduce BailSharel Ann AbadBelum ada peringkat

- 8.2 Rosario Panuncio Vs PEOPLEDokumen1 halaman8.2 Rosario Panuncio Vs PEOPLEmary grace bana100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- GA Law Enforcement Guide to Open Records ActDokumen39 halamanGA Law Enforcement Guide to Open Records ActLindsey Faye100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Go. v. CA (G.R. No. 101837, February 11, 1992)Dokumen2 halamanGo. v. CA (G.R. No. 101837, February 11, 1992)Christine CasidsidBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- 04133044Dokumen31 halaman04133044aaasdfasdfBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Decision: Court of AppealsDokumen16 halamanDecision: Court of AppealsBrian del MundoBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- 22 - Nala Vs Barroso Jr. - JimenezDokumen2 halaman22 - Nala Vs Barroso Jr. - JimenezVince Llamazares LupangoBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- MBE Notes and StrategiesDokumen16 halamanMBE Notes and StrategiesMrZee27100% (1)

- 138 - People vs. Belocura 679 SCRA 318Dokumen3 halaman138 - People vs. Belocura 679 SCRA 318Donna Faith ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8 BookletDokumen224 halamanCriminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8 Booklethesadi_5253Belum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- PAPER WARIOR Adventures of A Pro Se Litigant in Illinois' Corrupt Judicial SystemDokumen47 halamanPAPER WARIOR Adventures of A Pro Se Litigant in Illinois' Corrupt Judicial SystembollivarBelum ada peringkat

- Criminal Law 3 ProjectDokumen24 halamanCriminal Law 3 ProjectrituBelum ada peringkat

- In The Supreme Court of The United States: PetitionerDokumen27 halamanIn The Supreme Court of The United States: PetitionerAmen SunofraBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- REMREV CASE DIGEST Saluday v. PeopleDokumen1 halamanREMREV CASE DIGEST Saluday v. PeopleJune Karl CepidaBelum ada peringkat

- Lim, Et Al. vs. Ponce de Leon, Et Al. (66 SCRA 299)Dokumen3 halamanLim, Et Al. vs. Ponce de Leon, Et Al. (66 SCRA 299)Maria LopezBelum ada peringkat

- Terrorism" Under R.A. No. 9372 Entitled "An Act To Secure The StateDokumen9 halamanTerrorism" Under R.A. No. 9372 Entitled "An Act To Secure The StateEdz Votefornoymar Del Rosario0% (1)

- Amurao Notes Crim Law 2Dokumen137 halamanAmurao Notes Crim Law 2PhilipBrentMorales-MartirezCariagaBelum ada peringkat

- People Vs Villareal GR No. 201363Dokumen4 halamanPeople Vs Villareal GR No. 201363Suri LeeBelum ada peringkat

- People VS Pasudag, People VS Zuela, People VS Abe ValdezDokumen3 halamanPeople VS Pasudag, People VS Zuela, People VS Abe Valdezto be the greatestBelum ada peringkat

- CojuangcoDokumen5 halamanCojuangcoArwella GregorioBelum ada peringkat

- 5 People vs. Chua Ho SanDokumen2 halaman5 People vs. Chua Ho SanJemBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Barbri Outline - MBE-NY (2005) - Criminal Law & ProcedureDokumen17 halamanBarbri Outline - MBE-NY (2005) - Criminal Law & Proceduresab0714100% (2)

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on petitioners' motion for hospital confinementDokumen6 halamanPhilippines Supreme Court rules on petitioners' motion for hospital confinementStefan SalvatorBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digest Castillo Vs PPDokumen3 halamanCase Digest Castillo Vs PPAloma Grace JuicoBelum ada peringkat

- Ccase of People vs. Alvarado Et Al. GR 234048 2018Dokumen22 halamanCcase of People vs. Alvarado Et Al. GR 234048 2018Glenn Vincent Octaviano GuanzonBelum ada peringkat

- PEOPLE V JUDGE INTING G.R. No. 88919Dokumen3 halamanPEOPLE V JUDGE INTING G.R. No. 88919Christopher Ronn PagcoBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)