TG Attracting Best

Diunggah oleh

Ara E. CaballeroHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

TG Attracting Best

Diunggah oleh

Ara E. CaballeroHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Article at a glance

Baby boomers throughout the public sector are beginning to retire, creating a rare

opportunity for the US government to increase the caliber of its employees.

To compete successfully with private-sector employers, government agencies must

change their recruiting approach in four ways: prioritize talent management, make a

compelling case for public-sector employment, develop targeted recruiting strategies,

and streamline the hiring process.

Using this approach, the US government will be able to recruit the talent it needs to

fundamentally reshape its workforce for the longer term.

Attracting the best

Special report

J

a

m

e

s

S

t

e

i

n

b

e

r

g

1

Back to School: Rethinking Federal Recruiting

on College Campuses, Partnership for

Public Service, May 2006; The appeal of

public service: Who. . . what. . . and how?

The Council for Excellence in Government,

May 2008.

15

Widespread retirement in the US public sector, like most crises, presents an

opportunity as well as a challenge. On the one hand, the government faces the task of

persuading legions of talented individuals to work in the public sector rather than

take up more lucrative private-sector alternatives. On the other hand, the impending

exodus presents a rare chance to increase the caliber of government employees.

The challenge of attracting capable individuals to public service is certainly not insuper-

able, as nations such as France and Singapore have shown. In both countries, civil-

service jobs have historically been among the most sought after, and many young people

aspire to attend the prestigious schools that lead to government posts. The US public

sector does not have quite the same allure, but recent surveys indicate that the appeal

of public service is beginning to increasesuggesting that the government can indeed

attract high-quality talent.

1

Over the past two years, we have conducted many interviews with current and former

government employees and people who work in government-focused think tanks

or not-for-proft organizations. Based on these interviews and our work with several

government agencies, we identifed four changes that could substantially enhance

the US governments ability to acquire top talent. First, agency leaders must make talent

management a priority. Second, they must make a more compelling case for govern-

ment employment, emphasizing its many advantagesincluding interesting work, attrac-

tive benefts, job security, and upward mobility. Third, they should develop specifc

Thomas Dohrmann,

Cameron Kennedy, and

Deep Shenoy

In the pursuit of top talent, the US government faces stiff

competition from private-sector employers. But with

the right approach, government agencies can attract high-

caliber individuals to careers in public service.

Transforming Government Autumn 2008 16

strategies to source a wider range of candidates, rather than the generic recruiting

approach we generally see. Finally, they must modernize and streamline the hiring process.

Prioritize talent management

Several people we interviewed observed that senior government offcials prioritize

policy making over talent management and other managerial aspects of their jobs. One

noted that the head of her agency says all the right things about talent but ends up

distracted by policy issues.

Just as government offcials generally fail to devote enough time to determining and

carrying out a talent strategy, so too do most fail to hold their teams accountable for

ensuring that the right people are in place. Many agencies treat recruitment as a purely

process-oriented function to be left to HR. In one large government organization,

hundreds of people focus entirely on the recruiting process; fewer than ten think about

recruiting strategy. When senior executives do engage on talent issues, they tend to check

boxesis the agency hitting its hiring targets?rather than tackle strategic questions.

Former US Secretary of State Colin Powell is widely credited with transforming the State

Departments talent-management practices. He increased the departments recruiting

budget more than tenfold, sought additional resources from Congress to make it easier

for employees to do their jobs (for example, through training and by getting Internet

access on their computers, often less straightforward in government departments than

in corporations), and changed the evaluation process so that employees manage-

ment capabilitiesnot just their intellectual and technical skillswere considered in

promotion decisions. Employees at all levels talked about how these changes moti-

vated them. In a ranking of the best places to work among 30 large government agencies,

the State Department moved from 19th place in 2003 to 6th place in 2007, suggest-

ing that the impact has extended beyond Secretary Powells tenure.

2

Other agency leaders have personally involved themselves in upgrading the quality of

their talent pools. For example, at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which

has hired more than 2,000 new analysts since September 11, 2001, Director Robert

Mueller has put in place an ambitious program to attract talented analysts and

strengthen their training and development. All agencies should make talent a top priority

and adopt best practices of the kind the State Department and the FBI have pioneered.

Make a compelling case

Many interviewees were frustrated that the government does not always clearly communi-

cate the advantages of its own jobs. Some advantages are well known: generous bene-

fts and job security. Potential candidates may know less about the opportunities for

advancement, interesting and meaningful work, and the fexibility that is becoming

more important as more people seek a healthy worklife balance.

Where the benefts of public-sector work are well known, the government should ensure

that the details are understood by the kinds of candidates it wishes to attract and that

these candidates realize how few companies offer a similar range of benefts: retirement

2

The rankings, produced by the Partnership

for Public Service and American Universitys

Institute for the Study of Public Policy

Implementation, drew on responses from

more than 221,000 civil servants in 283

government organizations.

17 Special report: Attracting the best

savings plans, group life insurance, generous leave and vacation allowances (23 to

36 paid days off, not including sick days, compared with an average of 17 to 27 days in

the private sector), andperhaps most importantcomprehensive and affordable

health insurance.

Job security is likely to increase in importance to prospective candidates in a slowing

economy. According to the Department of Labor, annual turnover in the US government

is 7 to 8 percent, compared with 22 to 27 percent in the private sector.

Better yet, this job security comes with career-advancement opportunitiesresulting

not only from the coming wave of retirements but also from emerging needs for expertise

in areas such as high tech and national security. The government has also adopted

some performance-based promotion schemes to supplement the traditional grade-based

system. For example, the Presidential Management Fellows Program includes an

accelerated promotion track.

There are also other kinds of benefts. Government employees often work at the cutting

edge of a broad range of issues. A new lawyer might fnd himself immediately litigat-

ing voting-rights violations and participating in complex cases that a lawyer in private

practice would wait years to handle. An accountant might be deployed to untangle

new kinds of tax shelters. An engineer could work on designing mine-worker safety

guidelines. Few employers offer less experienced workers equivalent opportunities

to make an impact.

Finally, the government should emphasize job fexibility, which is greater in govern-

ment service than in most of the private sector. Many agencies allow employees to

ft 80-hour pay periods into eight days and take the other two days off. Family-friendly

working options such as telecommuting, fexible work schedules, and part-time and

job-sharing positions, combined with the availability of child care resources, will be

attractive to a wide range of candidatesespecially midlevel employees with families.

How should the case for government work be made? First, government literature can be

improved, in style as well as content. When one agency translated employment mate-

rials from government jargon into language that laymen would understand, candidates

expressed greater interest in government jobs. Other simple recruiting tactics that

agencies should always usebut often overlookinclude keeping HR materials up to

date, ensuring that information on USAjobs.gov is complete and accurate, and provid-

ing links, resources, and contacts for applicants seeking additional information.

More creative possibilities should also be considered. One of the most effective ways

to excite applicants about public service is to connect them with public-sector employees

with similar backgrounds. Applicant like recruitersfor example, freshly minted

The government should emphasize job exibility, which is greater in government

service than in most of the private sector

Transforming Government Autumn 2008 18

lawyers targeting law students or rookie analysts reaching out to aspiring analysts

generate signifcantly more interest from applicants because they allow applicants to

visualize themselves in the job. We have found, for example, that public-sector employees

in their twenties who give on-campus talks about their work and professional impact

draw 50 to 100 percent more job applications than the standard career-fair booth manned

by an HR manager or two.

Develop targeted strategies

Government agencies need a wide range of skills and capabilities, many of which are

quite specialized. Too often, however, they rely on applicants to seek out government jobs

rather than proactively identifying and targeting talent. When they are proactive, they

usually recruit from nearby campuses or the total labor market in major metropolitan

areas such as Washington or New York. We believe the government would beneft by

recruiting more aggressively and casting a wider net, with regard both to where it looks

for talent and to the kinds of candidates it seeks to attract.

Our research shows that in certain regions, the government has a competitive advantage

over other employers. For instance, government accountants are paid at least 4 percent

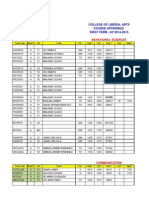

Exhibit

Salary competitiveness

varies

The government offers more competitive

wages than private employers in a number of

metro areas.

Average annual public-sector salary in selected US cities, % difference from private-sector average

Average salary defned as pay grade , step .

Average salary defned as pay grade , step .

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics; IRS data

Sacramento, CA

8

6

Houston, TX

9

0

Columbus, OH

10

4

Phoenix, AZ

14

8

Hartford, CT

7

3

Raleigh/Cary, NC

8

9

Denver, CO

2 10

Atlanta, GA

2 11

Washington, DC

9 17

Milwaukee, WI

2 7

Accountant

1

Accountant, managerial level

2

Special report: Attracting the best

more than private-sector accountants in about a dozen metro areas, including Phoenix,

Arizona; Columbus, Ohio; and Raleigh, North Carolina (exhibit). By shifting some

accounting jobs from Washingtonwhere government salaries tend to be lower than

private-sector salariesto one of these other markets, agencies can more easily

attract talented accountants. Nor should government agencies restrict themselves to

cities. In college towns or smaller towns near one or more universities, the govern-

ment is particularly likely to be able both to fnd high-quality talent and to offer com-

petitive compensation.

Moving a departments operations to a small town is not unknown in the public sector.

The Bureau of the Public Debt (BPD) moved more than 700 jobs from Washington

to Parkersburg, West Virginia (close to both West Virginia University and Ohio Valley

University), between 1992 and 1996, in part because it could not recruit enough

accountants and computer specialists in the DC area. Time and again, good candidates

accepted more lucrative jobs. Today, BPD is among the most attractive employers in

Parkersburg. We know of at least one other government agency considering transferring

certain IT-related jobs from metropolitan offces to a smaller city to attract higher-

caliber candidates.

To make a broader approach to sourcing talent effective, agencies should also tailor

the way they communicate their value proposition to people at three important points

in the professional life cycle: junior employees, midlevel managers, and executives

late in their career. For example, the Justice Department positions itself to new law-school

graduates as an ideal place to start a legal career because a stint there is impressive

to private-sector employers. Other agencies could use a similar strategy to attract new

entrants. For midlevel hires, agencies should approach experienced midcareer profes-

sionals whose interests and needs are well matched to the fexibility and benefts that

government jobs offer. For late-career hires, retireeswho bring deep skills and

long experience to the job on day onecan be strong candidates. A recent survey

3

found

that many baby boomers are seeking purpose driven work; the government is

extremely well positioned to fll this need, as well as to provide employee benefts impor-

tant to boomers, such as comprehensive, affordable health insurance and fexible

working arrangements.

We see public-sector recruiters beginning to court retirees from both government and

the private sector more aggressively. The Offce of Federal Procurement Policy is encourag-

ing agencies to take advantage of legislation that allows government retirees to fll

critical vacancies without disrupting their pensions. And a pilot program launched

by IBM, the US Treasury Department, and the Partnership for Public Service aims

to draw IBM retirees into federal service by making IBM employees aware of Treasury

vacancies before they retire and by advising them on the federal hiring process.

As part of their strategy for sourcing talent, government agencies must tailor not only

their recruiting messages but also the channels they use to communicate with the

constituencies they are trying to attract, and they should move away from the one-size-

fts-all recruiting approach that most agencies take. Market research (for example,

3

MetLife Foundation/Civic Ventures Encore

Career Survey, June 2008.

19

Transforming Government Autumn 2008 20

focus groups, surveys) and partnerships with other organizations can help agencies deter-

mine the right channels and refne their messages. For example, to target retirees

more effectively, agencies can partner with the AARP and employers that, like IBM, have

programs to help retiring workers transition into new careers.

Streamline the hiring process

The hiring process should demonstrate at every step that the government is a modern,

thoughtful employer. Our interviewees suggested that agencies should simplify

their recruitment and hiring processes, use better techniques to evaluate applicants, and

communicate more effectively with candidates about the status of their applications.

In many cases, the documents required for government job applications bear no rela-

tion to those typically required for private-sector or not-for-proft positions, which

means applicants must start from scratch when assembling materials. Furthermore,

job-application requirements vary across agencies. These burdens contrast with the

streamlined hiring practices of corporations and not-for-proft organizationsand even

governments elsewhere. The British Civil Service has a user-friendly application

process, with a series of tests and a universal assessment from which candidates can be

matched to positions in a number of different departments.

The complexity of submitting applications is not the only problem; unsophisticated

applicant screening is also an issue. Our interviewees noted that many public-sector

recruiters are poor at assessing candidates strengths and weaknesses. Candidates

who look terrifc on paper can disappoint in practice. To predict job performance

more accurately, all agencies could apply techniques such as cognitive exams and

structured interviews, which are already in use at some agencies, including the State

Department and the FBI.

The cognitive exam is typically a written test designed to measure a candidates intrinsic

skills, particularly those related to the job in question. The FBIs cognitive exam for

special agents, for instance, assesses mathematical reasoning and knowledge, data analysis

and interpretation skills, attention to detail, and ability to evaluate information.

A structured interview is one in which the employer asks precisely the same questions

of every candidate for a particular positionquestions directly related to the job

and its specifc requirements. Although many managers believe they can recognize talent

when they see it, evidence suggests that doing well in an unstructured interviewin

which the employer asks general questions about a candidates academic or professional

experiencedoes not always translate into strong job performance.

Once strong candidates have been identifed, they should be encouraged in every way

to accept an offer. Talented applicants typically have several offers to consider; their

The hiring process should demonstrate at every step that the government is

a modern, thoughtful employer

21

experience as candidates for government jobs should heighten their appetite for public

service, not diminish it. Even simple things, such as regularly updating candidates

on the status of their applications, can reduce the likelihood that a candidate will pursue

opportunities elsewhere. Agencies might also create a buddy system, in which candi-

dates are encouraged to approach particular employees with any questions they may

have. We have seen such programs successfully engage candidates, with a small

investment of time on the part of current employeesmany of whom are invigorated

by the knowledge that they are helping to usher in the next generation.

One area not comprehensively addressed here is the pay gap, an issue that makes

the government less competitive for certain positions, particularly senior-management

jobs. Government agencies may not be able to afford across-the-board increases in

compensation, but they can adopt market-based pay and pay-for-performance schemes

in certain areas. They should identify the most important job categories and, as

some agencies have successfully done, secure the legislative authority to introduce

fnancial incentives and adjust their pay schedules.

Over the coming years, the US government will lose an enormous number of workers.

By implementing the ideas we have outlined, it can fll these vacancies with highly

capable individuals. Not only would this address the short-term challenge, it would also

fundamentally reshape the government talent pool for the longer term.

Special report: Attracting the best

Thomas Dohrmann (Thomas_

Dohrmann@McKinsey.com) is a

principal in McKinseys Washington,

DC, ofce.

Cameron Kennedy (Cameron_

Kennedy@McKinsey.com)

is a consultant in the Washington,

DC, ofce.

Deep Shenoy (Deep_Shenoy@

McKinsey.com) is a consultant in

the Washington, DC, ofce.

Copyright 2008

McKinsey & Company. All rights

reserved.

Copyright 2008 McKinsey & Company

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Deloitte Millennial Model: An Approach To Gen Y ReadinessDokumen8 halamanDeloitte Millennial Model: An Approach To Gen Y ReadinessNeil TambeBelum ada peringkat

- Recruiting and Selection - Green FieldDokumen3 halamanRecruiting and Selection - Green FieldNikhil AlvaBelum ada peringkat

- Public Administration CourseworkDokumen7 halamanPublic Administration Courseworkbatesybataj3100% (2)

- Global Human Capital TrendsDokumen3 halamanGlobal Human Capital TrendsShivam KashyapBelum ada peringkat

- Human Resources Management in Public and Nonprofit Organizations (3rd Edition)Dokumen10 halamanHuman Resources Management in Public and Nonprofit Organizations (3rd Edition)mustamuBelum ada peringkat

- Public Services CourseworkDokumen7 halamanPublic Services Courseworkzehlobifg100% (2)

- Public Sector Personnel EconomicsDokumen53 halamanPublic Sector Personnel EconomicsRaphael CorbiBelum ada peringkat

- How To Write A Research Paper On UnemploymentDokumen6 halamanHow To Write A Research Paper On Unemploymentef71d9gw100% (1)

- Keeping Talent Strategies For Retaining Valued Federal Employees - (2011.01.19)Dokumen20 halamanKeeping Talent Strategies For Retaining Valued Federal Employees - (2011.01.19)hecarrionBelum ada peringkat

- Recruiting and Selecting Public WorkersDokumen18 halamanRecruiting and Selecting Public WorkersDeden abdur31Belum ada peringkat

- FAIR Institute: The Move To Insourcing (June 2009)Dokumen8 halamanFAIR Institute: The Move To Insourcing (June 2009)Christopher DorobekBelum ada peringkat

- Engaging Government Employees: Motivate and Inspire Your People to Achieve Superior PerformanceDari EverandEngaging Government Employees: Motivate and Inspire Your People to Achieve Superior PerformancePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (2)

- A Comparative Analysis of Job Satisfaction Among Public and Private Sector TeachersDokumen20 halamanA Comparative Analysis of Job Satisfaction Among Public and Private Sector TeachersTariq RahimBelum ada peringkat

- Preparing For Tomorrow: A Case Study of Workforce Planning in North Carolina Municipal GovernmentsDokumen25 halamanPreparing For Tomorrow: A Case Study of Workforce Planning in North Carolina Municipal GovernmentsIkram IELMAKIBelum ada peringkat

- Trends in Human Resource ManagementDokumen15 halamanTrends in Human Resource Managementangel lustaresBelum ada peringkat

- Labor-Management Relations Are The Policies and Practices Affecting The Relationship BetweenDokumen8 halamanLabor-Management Relations Are The Policies and Practices Affecting The Relationship BetweenFarhan RajaBelum ada peringkat

- Dissertation Topics For Public AdministrationDokumen7 halamanDissertation Topics For Public AdministrationDltkCustomWritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Coursework in Public AdministrationDokumen6 halamanCoursework in Public Administrationkylopuluwob2100% (1)

- Dissertation Topics in Public AdministrationDokumen8 halamanDissertation Topics in Public AdministrationSomeoneWriteMyPaperForMeUK100% (1)

- Public Administration DissertationsDokumen4 halamanPublic Administration DissertationsINeedSomeoneToWriteMyPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Human Resource Management and Government Performance: Why HRM MattersDokumen10 halamanHuman Resource Management and Government Performance: Why HRM MattersMirsada SijamicBelum ada peringkat

- Strengthening America’S Resource & Revitalizing American Workforce LeadershipDari EverandStrengthening America’S Resource & Revitalizing American Workforce LeadershipBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis On Graduate UnemploymentDokumen5 halamanThesis On Graduate Unemploymentsow1vosanyv3100% (2)

- Term Paper Public AdministrationDokumen7 halamanTerm Paper Public Administrationaflspyogf100% (1)

- Challenges of Public Personnel AdministrationDokumen6 halamanChallenges of Public Personnel AdministrationNur Athirah Peiruz100% (3)

- Public Administration Thesis TopicsDokumen4 halamanPublic Administration Thesis TopicsJoe Andelija100% (2)

- Getting It Right: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications From Research On Public-Sector Unionism and Collective BargainingDokumen32 halamanGetting It Right: Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications From Research On Public-Sector Unionism and Collective BargainingsachinBelum ada peringkat

- Neg - MMT Job Guarantee - Michigan 7 2023 BEJJPDokumen120 halamanNeg - MMT Job Guarantee - Michigan 7 2023 BEJJPbonnettesadieBelum ada peringkat

- Group One HRM and The NPMDokumen5 halamanGroup One HRM and The NPMAshenafiGetachewBelum ada peringkat

- Lateral Entry in Civil ServicesDokumen1 halamanLateral Entry in Civil Servicesantriksh168Belum ada peringkat

- Public Administration DissertationDokumen4 halamanPublic Administration DissertationPayForAPaperYonkers100% (1)

- Literature Review On Unemployment and GDPDokumen4 halamanLiterature Review On Unemployment and GDPgw1g9a3s100% (1)

- Progress JULY 18-19Dokumen1 halamanProgress JULY 18-19AdamProgressBelum ada peringkat

- PWC Succession Planning FinalDokumen32 halamanPWC Succession Planning FinalSahil SainiBelum ada peringkat

- Middle Level SkillsDokumen1 halamanMiddle Level SkillsDionesio OcampoBelum ada peringkat

- Public Sector HR Professionals Need To Step Back From The Day Job and Brace Themselves For The Challenges AheadDokumen4 halamanPublic Sector HR Professionals Need To Step Back From The Day Job and Brace Themselves For The Challenges AheadSalas DeshmukhBelum ada peringkat

- The Philippine Bureaucracy: Incentive Structures and Implications For PerformanceDokumen29 halamanThe Philippine Bureaucracy: Incentive Structures and Implications For PerformancepoloperBelum ada peringkat

- Workforce Development in the US: Changing Roles & Program EffectivenessDokumen47 halamanWorkforce Development in the US: Changing Roles & Program EffectivenessSadie MorhyBelum ada peringkat

- Public Sector Reform MauritiusDokumen2 halamanPublic Sector Reform MauritiusDeva ArmoogumBelum ada peringkat

- Transforming The Public SectorDokumen10 halamanTransforming The Public SectorqwertyBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper On Public AdministrationDokumen6 halamanResearch Paper On Public Administrationefecep7d100% (1)

- Research Paper On Public Administration TopicsDokumen7 halamanResearch Paper On Public Administration Topicsfzqs7g1d100% (1)

- AFP Illinois Public Sector CompensationDokumen14 halamanAFP Illinois Public Sector CompensationReboot IllinoisBelum ada peringkat

- The Talent EquationDokumen9 halamanThe Talent EquationSorin GheorgheBelum ada peringkat

- Labour Economics AssignmentDokumen8 halamanLabour Economics AssignmentMosisa ShelemaBelum ada peringkat

- Johansson BBR 2012Dokumen6 halamanJohansson BBR 2012Anonymous Feglbx5Belum ada peringkat

- Unemployment Term Paper ThesisDokumen6 halamanUnemployment Term Paper Thesisgjfcp5jb100% (2)

- Government's Content Strategy Is The Linchpin of Citizen ExperienceDokumen10 halamanGovernment's Content Strategy Is The Linchpin of Citizen ExperienceHank RoBelum ada peringkat

- Accenture High Performance Government Executive Summary State and LocalDokumen8 halamanAccenture High Performance Government Executive Summary State and LocalBrian MeshkinBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper On Human ServicesDokumen6 halamanResearch Paper On Human Servicesigmitqwgf100% (1)

- Dissertation On Public Service DeliveryDokumen8 halamanDissertation On Public Service DeliveryPaperWritingServicesReviewsSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Setting of Personnel AdministrationDokumen6 halamanSetting of Personnel AdministrationRodolfo Esmejarda Laycano Jr.100% (22)

- Jobs of The FutureDokumen30 halamanJobs of The FuturejobsmilesBelum ada peringkat

- HRD in Other SectorsDokumen147 halamanHRD in Other SectorsMandy Singh100% (4)

- Research Paper Unemployment RateDokumen5 halamanResearch Paper Unemployment Rateafnhinzugpbcgw100% (1)

- Commentary Governing To Deliver: Three Keys For Reinventing Government in Latin America and The CaribbeanDokumen9 halamanCommentary Governing To Deliver: Three Keys For Reinventing Government in Latin America and The CaribbeanNo SeiBelum ada peringkat

- At LDokumen4 halamanAt LElize MancolBelum ada peringkat

- Competing Through SustainabilityDokumen4 halamanCompeting Through SustainabilitySean SimBelum ada peringkat

- Research Paper UnemploymentDokumen7 halamanResearch Paper Unemploymentfvgczbcy100% (1)

- Strategic Cost ManagementDokumen16 halamanStrategic Cost ManagementAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Environmental SustainabilityDokumen10 halamanEnvironmental SustainabilityAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- The Different Population Trends in The Philippines and Other Asean CountriesDokumen4 halamanThe Different Population Trends in The Philippines and Other Asean CountriesAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Exercise - Replacement DecisionDokumen1 halamanExercise - Replacement DecisionAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- 2010 Accounting Alert - PFRS For SMEsDokumen56 halaman2010 Accounting Alert - PFRS For SMEsMary Joy BalbontinBelum ada peringkat

- Song ChartsDokumen5 halamanSong ChartsAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- ch12Dokumen32 halamanch12Ara E. Caballero100% (1)

- Exercise - Replacement DecisionDokumen1 halamanExercise - Replacement DecisionAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Exercise - Replacement DecisionDokumen1 halamanExercise - Replacement DecisionAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- IFRS For SMEs Basic Framework Oliver BucaoDokumen45 halamanIFRS For SMEs Basic Framework Oliver BucaoThessaloe B. FernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Financial Reporting and Management Reporting SystemsDokumen44 halamanFinancial Reporting and Management Reporting SystemsMichael ReedBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study-ThunderclapDokumen1 halamanCase Study-ThunderclapAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- 1T, Ay 2014-2015 AcgDokumen62 halaman1T, Ay 2014-2015 AcgAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Full IFRS Vs IFRS For SMEs PDFDokumen72 halamanFull IFRS Vs IFRS For SMEs PDFAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- Analyze Financial Statements with Ratios & TrendsDokumen80 halamanAnalyze Financial Statements with Ratios & TrendsAra E. Caballero100% (1)

- ACTBAS1 Adjusting EntriesDokumen14 halamanACTBAS1 Adjusting EntriesNat LiBelum ada peringkat

- Aquino. Caballero. Dulay. Feliciano. Olondriz. SusonDokumen16 halamanAquino. Caballero. Dulay. Feliciano. Olondriz. SusonAra E. CaballeroBelum ada peringkat

- PRAKTIS SOLUTIONS LIMITED - Company Accounts From Level BusinessDokumen7 halamanPRAKTIS SOLUTIONS LIMITED - Company Accounts From Level BusinessLevel BusinessBelum ada peringkat

- Sammeth V City of Seattle JudgementDokumen4 halamanSammeth V City of Seattle JudgementFinally Home RescueBelum ada peringkat

- World Bank Emerging Markets List and DefinitionDokumen7 halamanWorld Bank Emerging Markets List and DefinitionMary Therese Gabrielle EstiokoBelum ada peringkat

- Pay Fixation Ex ServiceDokumen2 halamanPay Fixation Ex ServiceDhirendra Singh PawarBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Religion in The Yugoslav WarDokumen16 halamanThe Role of Religion in The Yugoslav Warapi-263913260100% (1)

- Scenario #10: Diversity: Mediating MoralityDokumen5 halamanScenario #10: Diversity: Mediating Moralitybranmar2Belum ada peringkat

- OSB AdministrationDokumen156 halamanOSB AdministrationshekhargptBelum ada peringkat

- From Manhattan With LoveDokumen17 halamanFrom Manhattan With Lovejuliusevola1100% (1)

- Imbong V ComelecDokumen3 halamanImbong V ComelecDong OnyongBelum ada peringkat

- Philippine Politics and Government Quiz ReviewDokumen3 halamanPhilippine Politics and Government Quiz ReviewJundee L. Carrillo100% (1)

- WTC Transportation Hall Project 09192016 Interchar 212 +Dokumen17 halamanWTC Transportation Hall Project 09192016 Interchar 212 +Vance KangBelum ada peringkat

- PRESS RELEASE: Beyond The BeachDokumen2 halamanPRESS RELEASE: Beyond The BeachNaval Institute PressBelum ada peringkat

- Strategies To Practice Liberation Strategies To Dismantle OppressionDokumen2 halamanStrategies To Practice Liberation Strategies To Dismantle OppressionAri El VoyagerBelum ada peringkat

- Polytechnic University of The Philippines Taguig City CampusDokumen4 halamanPolytechnic University of The Philippines Taguig City CampusRoxane Rivera100% (2)

- Kapisanan NG MangagawaDokumen2 halamanKapisanan NG Mangagawaariel lapira100% (1)

- Dodoig 2023 001013Dokumen19 halamanDodoig 2023 001013GoRacerGoBelum ada peringkat

- Constitution 2 - Chapter 1 To 5 I CruzDokumen3 halamanConstitution 2 - Chapter 1 To 5 I CruzTweenieSumayanMapandiBelum ada peringkat

- WorkpermitDokumen2 halamanWorkpermitcloud2424Belum ada peringkat

- A Petition For Divorce by Mutual Consent Us 13 (B) of The Hindu Marriage AcDokumen2 halamanA Petition For Divorce by Mutual Consent Us 13 (B) of The Hindu Marriage AcManik Singh Kapoor0% (1)

- TerrorismDokumen33 halamanTerrorismRitika Kansal100% (1)

- Reyes v. TrajanoDokumen2 halamanReyes v. TrajanoSherry Jane GaspayBelum ada peringkat

- NEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Ugandan Peacekeeping Troops in Somalia Mark Tarehe Sita' DayDokumen6 halamanNEWS ARTICLE and SHOT LIST-Ugandan Peacekeeping Troops in Somalia Mark Tarehe Sita' DayATMISBelum ada peringkat

- David Matehuala-Grimaldo, A028 889 405 (BIA April 26, 2017)Dokumen6 halamanDavid Matehuala-Grimaldo, A028 889 405 (BIA April 26, 2017)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCBelum ada peringkat

- Town of Rosthern Coucil Minutes October 2008Dokumen4 halamanTown of Rosthern Coucil Minutes October 2008LGRBelum ada peringkat

- Case Digests (Executive Department) - PanesDokumen5 halamanCase Digests (Executive Department) - PanesYeaddaBelum ada peringkat

- Class 7 History I TERM Examination 2021-22Dokumen3 halamanClass 7 History I TERM Examination 2021-22Aadhinaathan AadhiBelum ada peringkat

- Macalintal v. Commission On ElectionsDokumen137 halamanMacalintal v. Commission On ElectionsChristian Edward CoronadoBelum ada peringkat

- Case Incident 2 CHP 12Dokumen10 halamanCase Incident 2 CHP 12Tika Shanti100% (1)

- NPC AdvisoryOpinionNo. 2017-063 PDFDokumen3 halamanNPC AdvisoryOpinionNo. 2017-063 PDFBanaNiBebangBelum ada peringkat

- Oliveboard Seaports Airports of India Banking Government Exam Ebook 2017Dokumen8 halamanOliveboard Seaports Airports of India Banking Government Exam Ebook 2017samarjeetBelum ada peringkat