J12 39893 Final

Diunggah oleh

Mireya Vilar CompteDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

J12 39893 Final

Diunggah oleh

Mireya Vilar CompteHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

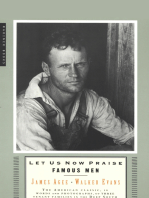

Households with Elderly Members in Mexico: Can Pensions or a Demogrant Help Facing Food Insecurity?

Mireya Vilar-Compte, Ibero-American University, Mexico Luis A. Ortiz-Blas, Ibero-American University, Mexico

Abstract: The objective of this article is to analyze the effect of pensions and of a subsidy for elderly persons in the propensity of households to be food insecure in Mexico. We analyzed cross-sectional data from the 2008 National Income and Expenditure Survey and compared food security status among households with elderly members who received pensions or a demogrant subsidy (exposed groups) and households with elderly members without such transfers (non-exposed groups). Propensity Score Matching was used to create comparable non-exposed groups. The exposed group of households receiving a pension were on average 6 percentage points more food secure than the non-exposed group; exposed households showed a significantly lower percentage of severe food insecure households (ranging from 2 to 4 percentage points). Those receiving a subsidy reported, on average, a significantly lower proportion of mild food insecurity (2 to 4 percentage points lower), and a greater proportion of low food insecurity (increase of 4 percentage points). Pensions and subsidies appear to have improved food security of households with elderly in Mexico, but the effects on actual food expenditure and diet are yet to be assessed. Findings are relevant to countries facing a demographic transition and that are likely to have elderly persons living with extended families. Keywords: Pensions, Public Subsidies, Food Security, Financial Contributions to Households

Introduction

exicos population demographics are shifting towards an older society. Seniors (those 65 years old and over) are becoming a growing proportion of the population. According to the Mexican National Census, in 2000 seniors represented 4.87 percent of the population, and increased to 6.18 percent in 2010 (INEGI 2010). This group is expected to increase to 12.5 percent in 2030 and to 22.6 percent in 2050 (CONAPO 2011). The life expectancy at age 65 has also increased. In 1970 life expectancy at age 65 was 14.8 years for women and 14.1 for men; in 2010 life expectancy at this age increased to 18.3 years for women and 16.3 for men (CONAPO 2011). This growing share of the senior population warrants an examination of their ability to have the financial resources to acquire a nutritious diet (Green et al. 2008), as well as the impact that they may have on the food security status of their households. Food insecurity is a multidimensional phenomenon defined as limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (Anderson 1990; Wolfe, Frongillo, and Valois 2003). In Mexico, the number of food-insecure individuals between 2008 and 2010 has remained stagnant at around 50 million (approximately 45 percent of all individuals). Nevertheless, the number of severe food-insecure individuals referring to the actual experience of hunger grew from 9.8 million (8.9 percent) in 2008 to 12.2 million (10.8 percent) in 2010 (CONEVAL 2011). According to the 2008 National Income and Expenditure Household Data (ENIGH) approximately 45.5 percent of the households with senior members were food insecure. Among elderly persons, food security is influenced by financial constraints, function disability, and isolation (Keller et al. 2007). Despite controversies surrounding the conceptualization and measurement of food insecurity among elderly persons (Wolfe, Frongillo, and Valois 2003), prior research has identified that older population subgroups such as lowincome households, and the oldest-old are significantly more at risk of food insecurity (Deeming 2011; Smith and Goldman 2007; de Snyder et al. 2005; Gonzalez-Gonzalez et al. 2011; Shamah-

The International Journal of Aging and Society Volume 2, 2013, agingandsociety.com/, ISSN 2160-1909 Common Ground, Mireya Vilar-Compte, Luis A. Ortiz-Blas, All Rights Reserved Permissions: cg-support@commongroundpublishing.com

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

Levy et al. 2008; Villanueva et al. 2009). It has also been highlighted that the deprivation represented by food insecurity contributes to poor health and nutrition, particularly among elderly persons (Lee and Frongillo 2001). Food insecurity can bring further physical and economic burdens to seniors as well as to the other household members they might live with. Issues concerning household structure and support for seniors in societies where families play a significant role in seniors lives are becoming increasingly important as population ages. The effects of these trends on families, households, and on the well-being of older adults are complex and not well documented (Bongaarts and Zimmer 2002; Devos 1990). For instance, in societies where elderly persons are likely to live in extended family arrangements i.e. families that include in one household near relatives in addition to the nuclear family the presence of an elderly member, and whether they contribute to family income through a pension or through cash-transfer programs, can affect food security outcomes of the household as a whole. For example, a study of the impact of the South African old age social pension revealed that the presence of a pensioner in a household significantly reduced adults and children missing meals when there was not enough money for food (Case and Menendez 2007). In Mexico an important proportion of the senior population still lives in both nuclear and extended families. Data from 2008 ENIGH reveals that only 12 percent of elderly persons live alone; the rest either lives in households headed by them or by non-elderly members. Households headed by an elderly member who do not live alone can be classified as: those living with her/his partner (20.2 percent), and those living with their partner and sons/daughters (44.3 percent). When the households are headed by a non-elderly member they can be categorized as: elderly members living in household headed by a son/daughter (8.9 percent), or elderly living in extended family arrangements (14.6 percent). Since income is a predictor of an individuals or households ability to access enough nutritious foods (Green et al. 2008), non-contributory cash-transfers (i.e. cash transfers that are not based on contributions to a pension plan) and means-tested schemes (i.e. those that provide financial assistance based on a persons income or assets) have been used in different countries as mechanisms to improve health and nutrition among elderly persons. For example, a study of the means-tested pension system implemented in South Africa revealed that when women received a pension it improved their self-reported health status (Case and Menendez 2007). Similarly, the Elderly Nutrition Program and the Food Stamp Program in the USA have been reported to have a positive impact on nutrient intake among low-income elderly, although the magnitude of the effects varies (Lee and Frongillo 2001; Kim and Frongillo 2007). Such programs have also shown an impact on other members of the household, especially on children. These effects have been reported for the means-tested pension in South Africa (Duflo 2003), as well as for a non-contributory cash-transfer pension in Bolivia (Barrientos 2006). 70 y Ms is a federal, non-contributory, cash-transfer and means-tested program for persons over 70 implemented in Mexico in 2007. The programs goal is to respond to the needs of an increasingly aging population in Mexico. Also, 70 y Ms was conceived as a program that could aid a largely vulnerable group, as most elderly persons in Mexico lack pensions and social security. Mexicos economy has been considerably based on an informal sector where employment does not offer retirement benefits or access to the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) nor to other institutes of social security. The IMSS manages the public pension scheme with the highest coverage. Other social security schemes (i.e. public oil company workers, government workers) are very similar to IMSS. The benefit package offered by IMSS and other institutions includes: health insurance, retirement pension, disability insurance, professional risk insurance, life insurance, day-care for workers, recreational and cultural facilities, and housing credits (Levy 2007; Levy 2008). All these benefits are bundled and are financed by a monthly contribution from the government and by a monthly payroll tax levied to the employer and the employee. Although in the 1990s some reforms that modified t he eligibility criteria of the pension schemes took place, generally, to obtain a pension its necessary

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

to satisfy a pre-established retirement age (usually 65 years with an option of early retirement at 60 years) and a minimum number of years of contribution (10 years of contribution before the 1997 reform and 25 years of contribution after the reform) (Aguila 2011). Since social security benefits including pensions and health insurance have historically depended upon labor status; this scheme led to having more than half of the population without health insurance coverage (among them an important proportion of elderly persons). Responding to this situation, in 2003 the Mexican Federal government decided to offer a Public Health Insurance, Seguro Popular, to all those citizens not covered by social security institutions. Since its implementation, the Seguro Popular has provided health coverage to nearly 50 million Mexicans. In spite of the achievements in providing greater access to health services, the majority of elderly persons do not receive a pension (i.e. around 55 percent according to ENIGH, 2008). This situation is especially distressing due to the association between lack of financial resources and food insecurity among the elderly population. In response to this situation, the Mexican federal government instituted the 70 y Ms program in 2007, which provided a monthly cash-transfer of around US $38, aimed at improving health and nutrition. Persons over 70 who lived in a locality whose population was under 10,000 people (SEDESOL 2011), and who did not receive cashtransfers from the poverty-reduction Oportunidades program, were eligible for 70 y Ms. Such demogrant (a grant based on demographic criteria), subsequently expanded to larger communities and also includes health promotion and personal development activities to improve the nutrition and health status of the elderly, as well as activities targeted at improving the social capital of the elderly and at providing information regarding access to services such as health care (i.e. through affiliation to the Public Health Insurance, Seguro Popular). Despite the impact that senior members can have on households food security, this phenomenon has, to our knowledge, not been studied. The adequacy of these public supports (both pensions and demogrants) to cover seniors needs and their consequent effect on households well-being are of paramount concern (Green et al. 2008). We could hypothesize that receiving either a pension or a demogrant would be inversely related with food insecurity among households with elderly. Furthermore, because in Mexico pensions offer greater financial benefits than demogrants, we could hypothesize that food insecurity would be diminished in greater proportion among those households receiving pensions than among those receiving demogrants. The purpose of this study was to assess the role of pensions and of a demogrant subsidy (program 70 y Ms) on the propensity of households to be food insecure, controlling for health, access to health care, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Data and Sample

We obtained data on treatment (i.e. receiving a pension or a demogrant), household food security level, and health and socio-demographic covariates from the 2008 National Income and Expenditure Survey (ENIGH). The ENIGH is a nationally representative survey that had a sample of 29,468 households and 118,927 individuals in 2008. We selected a subsample of 6,046 households with at least one elder member (aged 65 and over). From the subsample of households with at least one elderly member, two further subsamples were analyzed: households headed by an elderly member, and households with at least one member aged 70 and over. Given the differences in the characteristics of households that receive both a demogrant and a pension, they were excluded from the sample; these households represented 5.75 percent of the subsample of households with an elderly member. When compared to households with members receiving only pensions, households receiving both programs were significantly more rural and

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

less likely to be in municipalities with very low deprivation index, this is probably explained by the eligibility criteria of the Program 70 y Ms. In addition, members of the households receiving both programs had older members and reported more members with bad and very bad health status than households receiving only pensions. This could suggest that households with both programs were the needier; however, they also had better health status and fewer elder members than those only receiving the demogrant. In addition, we observed that those receiving both programs had higher disposable and current per capita incomes than any other subgroups and were also more likely to have double affiliation to health insurance programs (i.e. social security and Public Health Insurance Seguro Popular). This suggests that this group is likely to have better skills to navigate the system to obtain benefits from social programs, hence potentially addressing a selection bias issue. Despite having available data from 2010 ENIGH, the analysis was performed using 2008 ENIGH since the 2010 wave of data did not collect information on self-reported health status, which is a relevant variable when performing the analytical framework.

Measures of Food Security

Food security was measured through the Mexican Food Security Scale (EMSA), which is part of the 2008 ENIGH questionnaire and is comprised of 12 instruments that measure households perceptions regarding having and obtaining enough food to meet the dietary needs (CONEVAL 2010). This scale is an abbreviated version of the Latin-American and Caribbean Scale of Food Insecurity (ECLSA); which has been demonstrated to have excellent psychometric characteristics as well as convergence and criterion validity in previously published research (Perez-Escamilla 2009). Households were classified in food secure, low food insecure, mild food insecure, and severe food insecure categories based on 0, 1-3, 4-7 and 8-12 affirmative answers, respectively.

Measures of Intervention

Any individual aged 65 and over who reported receiving a pension, was assigned to be in the exposed group for pensions. For the demogrant program, since the eligibility criteria establishes being aged 70 and over, any individual in this age group was assigned to be in the exposed group for 70 y Ms if they reported receiving a demogrant cash-transfer subsidy from the government.

Other Measures

Health related covariates were included in the analysis. Measurements of self-reported health status were included. They were aggregated at the household level by averaging the number of members that reported bad or very bad health status. In addition, being affiliated to the Public Health Insurance (Seguro Popular) or to any social security institution was included as a proxy measure of access to health care. Municipality deprivation, rurality, household composition, and households income were included as proxy variables of socio -demographic measures. Municipality deprivation was measured through the Mexican Population Council (CONAPO) index of deprivation, which incorporates 9 indicators of education, population distribution, dwelling characteristics, and income, from the 2010 Mexican National Census. Rurality was defined based on the size of the community and categorized according to the thresholds established in 2008 ENIGH, as rural (under 2,499 inhabitants), semirural, (2,500-14,999), semiurban (15,000-99,999), and urban (over 100,000 inhabitants). Household composition was assessed through several indicators: household size, as well as the number of elderly members in the households (i.e. measured at three different thresholds 65, 70 and 85 years of age), and the average number of children under 5 years of age in the household. Finally, current and disposable monthly per capita incomes were computed at the household level. Income variables were transformed into a logarithmic scale when included in the inferential analysis.

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

Analysis

A secondary analysis of 2008 ENIGH was conducted. Descriptive statistics were analyzed using sample weights and complex survey design effects. Descriptive analyses were performed to assess the characteristics of households with senior members, to consider differences in households headed by an elderly member, and to display the characteristics of households with an elderly member that received pensions or demogrants. There were theoretical reasons to believe that pensions and subsidies from a demogrant could improve the food security status of households with elderly members. Ideally this relation would be examined through an experimental design where it could be measured. However, to our knowledge there are no experimental datasets available, among the population of interest to study how financial contributions of elderly members in households affect food security status. Therefore, we used the ENIGH 2008 a cross-sectional dataset to address this question through propensity score matching techniques. We first constructed a propensity score that estimated the probability of receiving a pension or a demogrant given a set of predictors, and we then created a non-exposed group (households with elderly not receiving a pension or a demogrant) and an exposed group (households with elderly receiving a pension or a demogrant) having similar propensity scores. Using the psmatch2 STATA command (Leuven E. 2003) we used two separate logit models to estimate the probability of receiving a pension and receiving a demogrant, given a set of covariates X. Kernel technique allowed us to match households with and without pensions or demogrants with similar propensity scores (Heinrich C. 2010). Assuming that outcomes are independent of participating in pensions and the program 70 y Ms, after controlling for propensity score, the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) would be: [ ( | [ ])] ( | [ ]) [ ( | [ ])] ( | [ ])

Where Pi=1 if the households with an elderly are receiving a pension and Pi=0 if not; and where the expectations [E] are conditional on treatment status. This implies that the ATTP is the difference between the proportion of food security level for those receiving a treatment (Y1) and for those not receiving it (Y0), after controlling for observable covariates with the propensity score p(Xi). Similarly, Di=1 if the household has an elderly receiving grants from 70 y Ms and Di=0 if not. In this case the rest of the assumptions are the same except that p(Xi) is based on a different set of covariates given differences in eligibility. Covariates in both models included: municipal deprivation index, household average selfreported bad or very bad health status, and the logarithm of households monthly per capita current income. These covariates mainly respond to factors affecting either eligibility criteria or the likelihood of having access to the demogrant subsidy or a pension. For example, living in a municipality with a high deprivation index is linked to eligibility criteria of the Program 70 y Ms, while a low municipal deprivation index increases the chances of finding formal jobs that in the long run can lead to having a pension. Similarly, having a good health status makes it more likely to have a formal job and a future pension, while having a bad health status increases the possibility of seeking social assistance. In addition and responding to different eligibility criteria, the logit model for demogrant subsidies also included the number of members aged 70 and over in the household, and being affiliated to the Public Health Insurance (Seguro Popular); both covariates respond to eligibility criteria characteristics. The analysis for pensions restricted the data to households with at least one member aged 65 years and older; the analysis for demogrants restricted data to households with at least one member aged 70 and over. In addition, the same analyses were performed restricting the data to households headed by an elderly member.

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

To ensure comparability, we tested the balancing properties using the pstest command in STATA, which performs a t-test of the covariates among exposed and non-exposed groups before and after matching (Heinrich C. 2010). It suggested adequate balancing properties. PSM analyses were performed without sample weights. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v. 11.

Results

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of households with elderly members (aged 65 and over). The subsample of households with elderly is further stratified according to whether or not an elderly member headed them, and whether or not they receive a pension, a demogrant, or neither of them. We first describe households with at least one elderly member (i.e. aged 65 and older). About half of these households were located in urban areas and around one quarter in rural areas. Approximately half of the households were located in municipalities with a very low deprivation index while one third in areas with a deprivation index ranging from very large to medium. Around half of the households had some level of food insecurity. In terms of access to health, it should be stressed that approximately one quarter of the households were uninsured. The average household size was estimated at 3.5, with an average of 0.16 children under 5 years old. About half of the households had at least one elderly member aged 70 and older, and around one quarter of the households had an elderly member aged 85 and older. As an average of their members self-reported health status, half of the households reported having bad or very bad health at the time of the interview. On average, households received a monthly pension of US$117 (MX$1,527), and/or a demogrant of approximately US$14 (MX$158). The monthly per capita mean current income of households was US$244 (MX$3,242) and the disposable income was US$212 (MX$2,755). Comparing households with elderly members over 65 with households headed by an elderly person, we found some significant differences. On average, households headed by an elderly person were smaller, had a slightly larger proportion of elderly members over 70 years, and a slightly lower proportion of elder members aged 85 and over, a lower average of children aged 5 years and younger, as well as a slightly higher pension and/or subsidy (i.e. demogrant). Also, they reported a better self-reported average health status (i.e. lower percentage of bad and very bad health-status). We then compared households with elderly members receiving pensions or demogrant subsidies to households not receiving any of these transfers. This helps to justify our subsequent analytical structure. Households receiving a pension were significantly more likely to be urban, and less likely to be semirural or rural. They were equally less likely to be located in municipalities with a deprivation index ranging from very high to medium. Additionally, they were more likely to have social security health coverage, and less likely to be uninsured. Their household structure was significantly different; having a smaller household size, fewer children aged 5 and younger, and a lower proportion of elderly aged 70 and over. On average, they reported a better self-reported health status, and they had a significantly higher monthly per capita current and disposable income. Given the eligibility criteria of the program 70 y Ms, among those households receiving this demogrant, a larger proportion were located in rural areas, as well as in municipalities with high and very high deprivation index. A larger proportion was covered by the Public Health Insurance (Seguro Popular), while a lower proportion was uninsured when compared to those not receiving any transfer. Households receiving the demogrant subsidy had a different household structure with more elderly members who were aged 70 and over, and also more members aged 85 and over. Not surprisingly, they also showed a worse self-reported health status. These households on average had more children aged 5 and younger than households not receiving transfers.

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

Table 1: Households Descriptive Statistics, Mexico, 2008 With elderly member, 65 yrs, without transfers 45.0 16.0 16.3 22.7 5.9 15.0 13.4 15.2 51.4 48.0 31.3 11.1 9.6

With elderly member, 65 yrs Rurality (%) Urban 49.7 Semi-urban 12.4 Semirural 13.6 Rural 24.3 Deprivation index (%) Very high 4.3 High 13.6 Medium 12.4 Low 14.4 Very low 55.3 Food security (%) Food secure 54.5 Low food insecure Mild food insecure Severe food insecure 27.7 9.5 8.3

Headed by an elderly member 65 yrsa

With elderly member, 65 yrs and with pensionb

With elderly member, 65 yrs and with subsidyc

49.4 12.3 13.4 24.9 4.3 13.7 12.9 14.2 54.9 55.0 27.6 8.9 8.5

74.1*** 13.0 7.4*** 5.5*** 0.3*** 2.9*** 4.2*** 14.5 78.1*** 70.9 19.6 5.5 4.1

19.4*** 4.8*** 17.0** 59.0*** 9.9*** 27.9*** 24.2*** 13.1 24.9*** 40.8 32.7 13.2 13.3

Health Insurance (%) Social 52.2 security Public Health Insurance Uninsured 17.8

52.6 17.3

88.9*** 2.0***

23.8*** 39.5***

36.2 21.0

24.3

25.1 56.1*** 10.9***

3.4*** 49.9*** 9.2*** 4,386 -4,650*** 4,052***

31.6*** 71.7*** 17.1*** -615 1,975 1,104

37.5 51.6 9.9 --2,766 2,318

Elderly members (%) 70 yrs 55.9 85 yrs 11.8

Pensions or subsidies, (mean, MX$) Pensions 1,527 1,657*** 70 y Mas 158 175*** Monthly income (per capita, MX$) Current 3,242 3,419 Disposable 2,755 2,913

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

With elderly member, 65 yrs Children <5 years (mean) Bad/very bad health status (mean) Household size (mean)

a

Headed by an elderly member 65 yrsa 0.13***

With elderly member, 65 yrs and with pensionb 0.12***

With elderly member, 65 yrs and with subsidyc 0.19***

0.16

With elderly member, 65 yrs, without transfers 0.18

48.5

46.7***

38.6***

64.1***

48.8

3.5

3.2***

3.4***

3.7

3.6

Significance tests report comparisons between households with an elderly member aged 65 and older, with those households headed by an elderly member. b Significance tests report comparisons between households with an elderly member aged 65 and older receiving a pension, with households with elderly members not receiving transfers. c Significance tests report comparisons between households with an elderly member aged 65 and older receiving a demogrant subsidy, with households with elderly members not receiving transfers. **P<0.05; ***P<0.01.

Table 2 shows the logit models for propensity scores for pensions both for all the households with any senior member aged 65 and over, as well as for a subsample of the households headed by an elderly aged 65 and over. Three continuous covariates were included average bad or very bad health status in the household, the logarithm of the per capita current income in the household, and the value of the deprivation index at the municipal level. Bad health status and the deprivation index were inversely related to the probability of receiving a pension, while households per capita current income was positively related to the probability of receiving a pension.

Table 2: Logit Model of the Propensity Score To Estimate the Effect of Receiving a Pension on Food Security at the Household Level, Mexico, 2008 Probability of receiving a pension (households with elderly members, 65 yrs ) Variable Average bad or very bad health status, household Log per capita household current income Municipal deprivation index Coefficient -.034 .421 -.029 Z-value -0.99 16.21 -12.93 P-value .321 .000 .000

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

Probability of receiving a pension (households headed by an elderly, 65 yrs ) Variable Average bad or very bad health status, household Log per capita household current income Municipal deprivation index Coefficient -.036 .405 -.034 Z-value -1.03 13.24 -11.34 P-value .303 .000 .000

Table 3 presents the same estimation for subsidies from the demogrant for all the households with any elderly member aged 70 and over, as well as for a subsample of the households headed by and elderly member aged 70 and over. In addition to average bad or very bad health status in the household, the logarithm of the per capita current income in the household, and the value of the deprivation index at the municipal level, this model also included another continuous covariate number of elderly members aged 70 and over in the household and a categorical one indicating whether or not the household was affiliated to the Public Health Insurance (Seguro Popular). Given the eligibility criteria for the demogrant 70 y Ms, all the covariates were positively related to the probability of receiving the subsidy.

Table 3: Logit Model of the Propensity Score To Estimate the Effect of Receiving a Subsidy from 70 y Ms on Food Security at the Household Level, Mexico, 2008 Probability of receiving a demogrant (households with elderly members, 70 yrs ) Variable Coefficient Z-value P-value Average bad or very bad health status, household Affiliation to Public Health Insurance (Seguro Popular) n of elderly 70 yrs Log per capita household current income Municipal deprivation index .105 .488 3.32 8.12 .001 .000

.376 .049 .025

6.12 1.40 10.60

.000 .162 .000

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

Probability of receiving a demogrant (households headed by an elderly, 70 yrs ) Variable Average bad or very bad health status, household Affiliation to Public Health Insurance n of elderly 70 yrs Log per capita household current income Municipal deprivation index Coefficient .117 .445 .314 .019 .026 Z-value 3.06 6.47 4.66 0.48 9.91 P-value .002 .000 .000 .634 .000

Table 4 presents differences in food security outcomes between households with and without pensions. On average, pension recipients reported, a greater percentage of food security, and a lower percentage of any level of food insecurity (i.e. low, mild or severe). After propensity matching, the differences between food security and severe food insecurity became significant for households with at least one elderly member, as well as for households headed by an elderly member. Among households headed by an elderly member or among those with at least one elderly member (aged 65 and over), the exposed group (i.e. with pension) was on average, 6 percentage points more food secure than those households headed by an elderly member but not receiving a pension. Inversely, exposed households were on average 4 percentage points less severe food insecure that the non-exposed group. Significantly lower levels of low food insecurity, by 3 percentage points, were only reported by households with an elderly member but not necessarily by households headed by them.

Table 4: Average Effect of Pensions on Food Security Status among Households with Elderly Members, Mexico, 2008 ATT of receiving a pension (households with elderly members, 65 yrs ) Outcome variable Exposed Secure Low insecurity Mild insecurity Severe insecurity .73 .17 .05 .05 Matched

Non-exposed .67 .20 .07 .07

Difference .06 -.03 -.02 -.02

t-stat 3.70*** -1.99** -1.08NS -2.36**

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

ATT of receiving a pension (households headed by an elderly member, 65 yrs) Outcome variable Exposed Secure Low Mild Severe .72 .18 .06 .04 Matched

Non-exposed .66 .20 .07 .08

Difference .06 -.02 -.01 -.04

t-stat 3.41** -1.42NS -0.90NS -2.85**

**P<0.05; ***P<0.01. ATT, average treatment effect on the treated (exposed group); NS, not significant.

Finally, Table 5 shows differences in food security status among households with elderly members aged 70 and over with and without subsidies from the demogrant 70 y Ms. Those receiving the subsidy reported, on average, a significantly lower proportion of mild food insecure households (a reduction ranging from 2 to 4 percent) and a greater proportion of low insecure households (of approximately 4 percent). These findings were reported both in households headed by an elderly member aged 70 and older, as well as by households with at least one elderly member but not necessarily headed buy them. On the sensitivity analyses, we performed the effect of subsidies from the demogrant on households with elderly members aged 65 and over (as well as headed by an elderly member aged 65 over). The results were very similar in their direction and significance (although results were significant in all cases at p<0.05), but the magnitude of the effects was smaller. This may result from having households without eligible individuals for the demogrant 70 y Ms, hence diluting the effect of the program. On the other hand, increases in significance may come from a larger subsample.

Table 5: Average Effect of a Demogrant on Food Security Status among Households with Elderly Members, Mexico, 2008 ATT of receiving a subsidy (households with elderly members, 70 yrs ) Outcome variable Exposed Secure Low Mild Severe .41 .34 .13 .13 Matched

Non-exposed .42 .30 .15 .12

Difference -.01 .04 -.02 .01

t-stat -.64NS 1.91* 1.91* .19NS

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

ATT of receiving a subsidy (households headed by an elderly member, 70 yrs) Outcome variable Exposed Secure Low Mild .41 .35 .11 Matched

Non-exposed .42 .31 .15

Difference -.01 .04 -.04

t-stat -.60NS 1.87* -2.19**

Severe .13 .12 .01 .40NS *P<0.1, **P<0.05; ***P<0.01. ATT, average treatment effect on the treated (exposed group); NS, not significant.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that among households with elderly members, receiving a pension improves the food security status of the household. This finding is consistent with what Case and Menedez (2007) observed with South African household that receive old age pensions. On the other hand, households with elderly members who receive a demogrant which is substantially low in financial terms when compared to the amount obtained by a pension moved from moderate to low food insecurity status. In countries like Mexico where elderly persons are increasing as a percentage of the population, and are likely to live in nuclear and extended families, assessing the dynamics of these families will become an important issue for aging research and policy. An example is given by the propensity of households with an elderly member to be food insecure. The current study demonstrates the effect that financial contributions of elderly members within the household have on the perception of food security. However, whether this perception of food security translates into a better diet remains a focus for future research. It would be necessary to assess how pensions or demogrant subsidies actually affect the decision making process on how to spend on foods for the household. Additionally, it would be important to evaluate the effect of such financial transfers into the actual well-being of elderly persons (i.e. nutritional and health status), as anecdotal evidence has identified that some of the financial contributions provided by elderly members are invested in the household and not necessarily on a better nutrition for the older members. Even though the analysis of the demogrant from 70 y Ms showed an improvement for households moving from moderate to low food insecurity the effect is modest. This may partially result from the fact that the implementation window of the program was short considering that its implementation started in 2007. A pending issue from a policy perspective regards aid to elderly without social insurance coverage, as this implies a population group that is 65 years or older, that does not receive a pension, and that due to the eligibility criteria of the 70 y Ms program does not receive other subsidies either. Currently, there are plans to expand the programs specifically to poor urban and semi-urban areas, which would not necessarily cover this age group. It would be relevant to assess the characteristics and food security implications of this subgroup in future analyses. Structure of households and families are complex and dynamic, understanding the effect of the role of elderly persons as society ages will be of interest to target policies assertively (De Vos, Solis, and De Oca 2004). Revisiting notions of extended family and of those regarding who

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

takes care of older members may warrant future attention in assessing the effect that pensions and subsidies have on nutrition and health outcomes (Doubova et al. 2010).

Limitations

This study has limitations. It is cross-sectional in nature; although this implies that the analysis captures a single point in time, no better data was available, and given the scarcity of studies on aging and nutrition in Mexico, this is thought to be a relevant starting point. Although we controlled for variables that influence receiving a pension or a subsidy, other factors could have made the individual within a given household (e.g. objective health status, number of people contributing in a given household, valuation of other benefits bundled in the pensions and program 70 y Ms) more prone to receiving such financial transfers. The analytical approach also assumed as it is commonly done when using PSM (Sosa-Rubi, Galarraga, and LopezRidaura 2009; Heinrich C. 2010) that unobservable components would not substantially bias the analysis .

Conclusions

Household structure and support for elderly persons in societies were families provide significant support is becoming increasingly important as population ages. In Mexico, the effects social programs such as social security pensions and demogrant subsides in the socioeconomic and health status of households with elderly members is complex and not well documented. The perspective provided by this study is, to our knowledge, pioneer. We assessed the impact that such types of programs have on the food security status of households with elderly members. Such outcome measure potentially informs both socioeconomic and nutritional impacts of financial transfers to elderly and its impacts on households. The results suggest the need for further study in this area and underscore its relevance for the ageing policy agenda. Future research should focus on how the money received from pensions and demogrants is spent by household members, if food consumption changes, and if so, what food purchases are increased. Also, future study in this field should investigate which household members benefit from the pension or demogrant, as well as the specific effect these cash-transfers have on elderly persons health status.

Authors Contribution

M. Vilar-Compte planned the study, wrote the paper, and supervised the data analysis. L.A. Ortiz-Blas performed the data analysis and contributed to the final draft.

Acknowledgements

We thank the comments and support of Ana Bertha Prez Lizaur and Ana Bernal Stuart for her help in editing and finishing the last version of this document.

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGING AND SOCIETY

REFERENCES

Aguila, E. 2011. Personal Retirement Accounts and Saving. American Economic JournalEconomic Policy 3 (4):1-24. Anderson, S. A. 1990. Core Indicators of Nutritional State for Difficult-to-Sample Populations. Journal of Nutrition 120 (11):1559-1599. Barrientos, A. 2006. Poverty reduction: The missing piece of pension reform in Latin America. Social Policy & Administration 40 (4):369-384. Bongaarts, J., and Z. Zimmer. 2002. Living arrangements of older adults in the developing world: An analysis of demographic and health survey household surveys. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 57 (3):S145-S157. Case, A., and A. Menendez. 2007. Does money empower the elderly? Evidence from the Agincourt demographic surveillance site, South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 35:157-164. CONAPO. 2011. Diagnstico Socio-Demogrfico del Envejecimiento en Mxico. CONEVAL. 2010. Dimensiones de la Seguridad Alimentaria: Evaluacin Estratgica de Nutricin y Abasto. edited by CONEVAL. . 2011. Anexo Estadstico del Informe de Medicin de Pobreza 2010. de Snyder, V. N. S., T. Gonzalez-Vazquez, B. Jauregui-Ortiz, and P. Bonilla-Fernandez. 2005. Ageing and health among rural men. Salud Pblica de Mxico 47 (4):294-302. De Vos, S., P. Solis, and V. M. De Oca. 2004. Receipt of assistance and extended family residence among elderly men in Mexico. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 58 (1):1-27. Deeming, C. 2011. Food and Nutrition Security at Risk in Later Life: Evidence from the United Kingdom Expenditure & Food Survey. Journal of Social Policy 40:471-492. Devos, S. 1990. EXTENDED FAMILY LIVING AMONG OLDER-PEOPLE IN 6 LATINAMERICAN COUNTRIES. Journals of Gerontology 45 (3):S87-S94. Doubova, S. V., R. Perez-Cuevas, P. Espinosa-Alarcon, and S. Flores-Hernandez. 2010. Social network types and functional dependency in older adults in Mexico. Bmc Public Health 10. Duflo, E. 2003. Grandmothers and granddaughters: Old-age pensions and intrahousehold allocation in South Africa. World Bank Economic Review 17 (1):1-25. Gonzalez-Gonzalez, C., S. Sanchez-Garcia, T. Juarez-Cedillo, O. Rosas-Carrasco, L. M. Gutierrez-Robledo, and C. Garcia-Pena. 2011. Health care utilization in the elderly Mexican population: Expenditures and determinants. Bmc Public Health 11. Green, R. J., P. L. Williams, C. S. Johnson, and I. Blum. 2008. Can Canadian seniors on public pensions afford a nutritious diet? Canadian Journal on Aging-Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement 27 (1):69-79. Heinrich C., A. Maffioli, G. Vzquez. 2010. A Primer for Applying Propensity Score Matching. In Impact-Evaluation Guidelines. Technical Notes. Washington DC: Interamerican Development Bank. INEGI. 2010. Principales resultados del Censo de Poblacin y Vivienda 2010. edited by INEGI. Keller, H. H., J. J. M. Dwyer, V. Edwards, C. Senson, and H. G. Edward. 2007. Food security in older adults: Community service provider perceptions of their roles. Canadian Journal on Aging-Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement 26 (4):317-328. Kim, K., and E. A. Frongillo. 2007. Participation in food assistance programs modifies the relation of food insecurity with weight and depression in elders. Journal of Nutrition 137 (4):1005-1010. Lee, J. S., and E. A. Frongillo. 2001. Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among US elderly persons. Journal of Nutrition 131 (5):1503-1509.

VILAR-COMPTE & ORTIZ-BLAS: HOUSEHOLDS WITH ELDERLY MEMBERS IN MEXICO

Leuven E., B. Sianesi. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing , April 2012 2003. Available from http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html. Levy, S. 2007. Can social programmes reduce productivity and economic growth? A hypothesis for Mexico. Trimestre Economico 74 (295):491-540. Levy, Santiago. 2008. Good Intentions, Bad Outcomes Social Policy, Informality, and Economic Growth in Mexico: Brooking Institution Press. Perez-Escamilla, R. 2009. THE LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN HOUSEHOLD FOOD SECURITY MEASUREMENT SCALE (ELCSA). Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 55:70-70. SEDESOL. 2011. Reglas de Operacin del Porgrama 70 y Ms 2011. edited by SEDESOL. Shamah-Levy, T., L. Cuevas-Nasu, V. Mundo-Rosas, C. Morales-Ruan, L. CervantesTurrubiates, and S. Villalpando-Hernandez. 2008. Health and nutrition status of older adults in Mexico: Results of a national probabilistic survey. Salud Pblica de Mxico 50 (5):383-389. Smith, K. V., and N. Goldman. 2007. Socioeconomic differences in health among older adults in Mexico. Social Science & Medicine 65 (7):1372-1385. Sosa-Rubi, S. G., O. Galarraga, and R. Lopez-Ridaura. 2009. Diabetes treatment and control: the effect of public health insurance for the poor in Mexico. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87 (7):512-519. Villanueva, J., A. Pena, Z. G. Calderon, and G. Betanzos. 2009. Nutrition and frailty in older people de Mexico: principles of intervention. Revista Espanola De Nutricion Comunitaria-Spanish Journal of Community Nutrition 15 (4):218-228. Wolfe, W. S., E. A. Frongillo, and P. Valois. 2003. Understanding the experience of food insecurity by elders suggests ways to improve its measurement. Journal of Nutrition 133 (9):2762-2769.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Mireya Vilar-Compte: Mireya Vilar Compte, PhD, is an associate professor in the Health Department at the Universidad Iberoamericana. Her research agenda includes financial protection in health among vulnerable groups (i.e. elderly and immigrants), aging and nutrition, and food insecurity. Her most recent research assesses the impact of food security on health outcomes among urban older adults. She holds a PhD and an MPhil in public administration from New York University, as well as an MPP from the University of York. As part of her professional experience, she worked for more than two years as a health specialist at the World Bank. Luis A. Ortiz-Blas: Luis Ortiz-Blas was a reseach assistant at Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico, at the time this research was conducted. He holds an MSc in health economics from Barcelona Graduate School of Economics. As a part of his professional experience he worked for more than two years as a junior professional sssociate at the World Bank.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 14 - JAVIER Revised 021319Dokumen16 halaman14 - JAVIER Revised 021319Lexter AndersonBelum ada peringkat

- Factors That Affect Normal Functioning of The Older PersonsDokumen8 halamanFactors That Affect Normal Functioning of The Older PersonsFielMendoza0% (1)

- Factors That Affect Normal Functioning of The Older Persons: Assignment Nec 2Dokumen8 halamanFactors That Affect Normal Functioning of The Older Persons: Assignment Nec 2FielMendozaBelum ada peringkat

- Morgan Lagueux - Final Draft Research PaperDokumen6 halamanMorgan Lagueux - Final Draft Research Paperapi-548143942Belum ada peringkat

- Nações Unidas Relatório 2023Dokumen4 halamanNações Unidas Relatório 2023BzBelum ada peringkat

- Soci 290 Assignment 3Dokumen6 halamanSoci 290 Assignment 3ANA LORRAINE GUMATAYBelum ada peringkat

- SR 1Dokumen12 halamanSR 1Amalia RiaBelum ada peringkat

- Scholarly PaperDokumen7 halamanScholarly Paperapi-433700464Belum ada peringkat

- Malnutrisi Bertanggung Jawab untuk Banyak PenderitaanDokumen5 halamanMalnutrisi Bertanggung Jawab untuk Banyak PenderitaanPutri Ajeng SawitriBelum ada peringkat

- Income Inequality and Health Status: A Nursing Issue: AuthorsDokumen5 halamanIncome Inequality and Health Status: A Nursing Issue: AuthorsWinni FebriariBelum ada peringkat

- Addressing Geriatric Malnutrition: Can Social Protection Work?Dokumen4 halamanAddressing Geriatric Malnutrition: Can Social Protection Work?International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyBelum ada peringkat

- Running Head: FOOD INSECURITY 1Dokumen8 halamanRunning Head: FOOD INSECURITY 1Peter KamauBelum ada peringkat

- Social Science & Medicine: Timothy Powell-Jackson, Sanjay Basu, Dina Balabanova, Martin Mckee, David StucklerDokumen9 halamanSocial Science & Medicine: Timothy Powell-Jackson, Sanjay Basu, Dina Balabanova, Martin Mckee, David StucklermuhromBelum ada peringkat

- Causes of Health Inequality: Income, Education, Childhood, or EnvironmentDokumen20 halamanCauses of Health Inequality: Income, Education, Childhood, or EnvironmentLisaBelum ada peringkat

- Marielle Masnour Article SampleDokumen6 halamanMarielle Masnour Article SampleMarielle K. MansourBelum ada peringkat

- Stereotypes About Old AgeDokumen22 halamanStereotypes About Old AgeAdrián DelgadoBelum ada peringkat

- Heterogeneous Factors Predict Food Insecurity Among The Elderly in Developed Countries: Insights From A Multi-National Analysis of 48 CountriesDokumen12 halamanHeterogeneous Factors Predict Food Insecurity Among The Elderly in Developed Countries: Insights From A Multi-National Analysis of 48 CountriesbibrevBelum ada peringkat

- Social Economic and Health - EssayDokumen3 halamanSocial Economic and Health - EssayGillBelum ada peringkat

- Sso 390 Reflection PaperDokumen7 halamanSso 390 Reflection Paperapi-607585906Belum ada peringkat

- Vulnerable Populations IIDokumen6 halamanVulnerable Populations IISandra AshburnBelum ada peringkat

- Experiment Incentive Based Welfare Impact Progesa Health MexicoDokumen29 halamanExperiment Incentive Based Welfare Impact Progesa Health MexicoJuan FiallosBelum ada peringkat

- Malnutrition Prevalence Among Children and Women of Reproductive Age in Mexico by Wealth, Education Level, Urban/rural Area and Indigenous EthnicityDokumen12 halamanMalnutrition Prevalence Among Children and Women of Reproductive Age in Mexico by Wealth, Education Level, Urban/rural Area and Indigenous EthnicityAnaBelum ada peringkat

- Center for Abused Elderly ReviewDokumen16 halamanCenter for Abused Elderly ReviewKhea Micole May FernandoBelum ada peringkat

- Health Promotion ProjectDokumen10 halamanHealth Promotion Projectapi-339312954Belum ada peringkat

- 83 Life ExpectancyDokumen5 halaman83 Life ExpectancyLe HuyBelum ada peringkat

- Final Health Policy 2023Dokumen10 halamanFinal Health Policy 2023api-679675055Belum ada peringkat

- NRSG 780 - Understanding Health DisparitiesDokumen24 halamanNRSG 780 - Understanding Health DisparitiesjustdoyourBelum ada peringkat

- Poverty Has Been Defined As A Situation Where An Individual Cannot Acquire Basic Needs Due To Lack of IncomeDokumen4 halamanPoverty Has Been Defined As A Situation Where An Individual Cannot Acquire Basic Needs Due To Lack of IncomeOscar MosesBelum ada peringkat

- Geriatric NursingDokumen30 halamanGeriatric NursingVyasan Joshi100% (2)

- 473 in Sickness and Wealth DiscussionDokumen7 halaman473 in Sickness and Wealth Discussionapi-678203412Belum ada peringkat

- Arber Et Al. - 2014 - Subjective Financial Well-Being, Income and HealthDokumen26 halamanArber Et Al. - 2014 - Subjective Financial Well-Being, Income and HealthAndreea UrzicaBelum ada peringkat

- Perspectives of AgingDokumen44 halamanPerspectives of AgingEva Boje-JugadorBelum ada peringkat

- HLTH 304Dokumen6 halamanHLTH 304api-625956578Belum ada peringkat

- The Role of United Nations Intergovernmental Agencies and Non Governmental Agencies in Solving Nutritional Problems at Community LevelDokumen18 halamanThe Role of United Nations Intergovernmental Agencies and Non Governmental Agencies in Solving Nutritional Problems at Community LevelArslan KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Nutrition in Aging: Nancy S. Wellman, PHD, RD, Fada Barbara J. Kamp, MS, RDDokumen18 halamanNutrition in Aging: Nancy S. Wellman, PHD, RD, Fada Barbara J. Kamp, MS, RDampalacios1991Belum ada peringkat

- Final Chapter 2 RRLDokumen17 halamanFinal Chapter 2 RRLStephanie Joy EscalaBelum ada peringkat

- Ageing and Health: A Briefing On As Part of The 30 September 2021Dokumen27 halamanAgeing and Health: A Briefing On As Part of The 30 September 2021Gleh Huston AppletonBelum ada peringkat

- Health Promotion Final PaperDokumen14 halamanHealth Promotion Final Paperapi-598929897Belum ada peringkat

- Poverty's Influence On The Health of America 1Dokumen15 halamanPoverty's Influence On The Health of America 1api-281018238Belum ada peringkat

- Effects of Homelessness On The ElderlyDokumen18 halamanEffects of Homelessness On The ElderlyLoganGeren100% (1)

- The Impact of A Home-Delivered Meal Program On Nutritional Risk Dietary Intake Food Security Loneliness and SociaDokumen11 halamanThe Impact of A Home-Delivered Meal Program On Nutritional Risk Dietary Intake Food Security Loneliness and SociaCaylynn WoWBelum ada peringkat

- Concept Paper On The Rising Need For Long Term Care Support For The Traditional Filipino CaregiverDokumen27 halamanConcept Paper On The Rising Need For Long Term Care Support For The Traditional Filipino CaregiverKay Ramos JimenoBelum ada peringkat

- Social DeterminantsDokumen4 halamanSocial DeterminantsAaramBelum ada peringkat

- Hunt JurnalDokumen29 halamanHunt JurnalLily NGBelum ada peringkat

- TANGPOS - ABE 159 Reaction PaperDokumen2 halamanTANGPOS - ABE 159 Reaction Paperromulus.tangpos001Belum ada peringkat

- Perforasi GIDokumen42 halamanPerforasi GIaliqulsafikBelum ada peringkat

- Forward Thinking and Family Support: Explaining Retirement and Old Age Labor Supply in IndonesiaDokumen59 halamanForward Thinking and Family Support: Explaining Retirement and Old Age Labor Supply in IndonesiaDoãn Tâm LongBelum ada peringkat

- Health & PlaceDokumen10 halamanHealth & PlaceBeatriz Elena JaramilloBelum ada peringkat

- Poverty, human rights and food insecurityDokumen6 halamanPoverty, human rights and food insecurityYazir SaldañaBelum ada peringkat

- The Macro-Social Environment and HealthDokumen17 halamanThe Macro-Social Environment and HealthSophia JohnsonBelum ada peringkat

- Issue Brief: Re-Examining Hunger in The USDokumen16 halamanIssue Brief: Re-Examining Hunger in The USAnnelise McGowanBelum ada peringkat

- Aging in Mexico, Population Trends and Emerging IssuesDokumen10 halamanAging in Mexico, Population Trends and Emerging IssuesDaniela OrozcoBelum ada peringkat

- Y10 GP TP Team BDokumen22 halamanY10 GP TP Team BZeeshan HassanBelum ada peringkat

- Policy Analysis Paper-Sw 4710-MeadowsDokumen9 halamanPolicy Analysis Paper-Sw 4710-Meadowsapi-250623950Belum ada peringkat

- Malnutrition in ChildrenDokumen3 halamanMalnutrition in ChildrenvandrestBelum ada peringkat

- 10 1 1 697 7643 PDFDokumen38 halaman10 1 1 697 7643 PDFDzila jeancy grâceBelum ada peringkat

- Lee 2011Dokumen18 halamanLee 2011WWZBelum ada peringkat

- Future Outlook of Food Insecurity For The Elderly and DisabledDokumen6 halamanFuture Outlook of Food Insecurity For The Elderly and DisabledJennifer DealBelum ada peringkat

- Ef6oano Inglesbasico 180711024501 PDFDokumen128 halamanEf6oano Inglesbasico 180711024501 PDFfilipamineiroBelum ada peringkat

- Concept and Scope of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA)Dokumen3 halamanConcept and Scope of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA)nikka csmBelum ada peringkat

- Pilgrim - S Pride Poultry Records 2017 PDFDokumen41 halamanPilgrim - S Pride Poultry Records 2017 PDFAnonymous NSKPIwI1Belum ada peringkat

- Soal Bahasa InggrisDokumen31 halamanSoal Bahasa InggrisFuhr HeriBelum ada peringkat

- Design and Development of Fruit WasherDokumen11 halamanDesign and Development of Fruit WasherRafael SantosBelum ada peringkat

- BOOSTDokumen16 halamanBOOSTChristous PkBelum ada peringkat

- French BreadDokumen10 halamanFrench BreadtvmBelum ada peringkat

- 1468816857summer Vacation HomeworkDokumen16 halaman1468816857summer Vacation Homeworkkaran girdharBelum ada peringkat

- The Above Dry Ginger Method of DR - Hitesh Jani Is Highly Recommended byDokumen9 halamanThe Above Dry Ginger Method of DR - Hitesh Jani Is Highly Recommended bySayyapureddi SrinivasBelum ada peringkat

- Insdag Report PDFDokumen51 halamanInsdag Report PDFJay ParmarBelum ada peringkat

- Nutri LiteDokumen78 halamanNutri LiteJuanBelum ada peringkat

- Unit 6 General Test: Listen To The Conversations. Then Choose The Word or Phrase That Correctly Completes Each SentenceDokumen7 halamanUnit 6 General Test: Listen To The Conversations. Then Choose The Word or Phrase That Correctly Completes Each SentenceGokú Del Universo 780% (5)

- Patterns of Mobile Device Use by Caregivers and Children During Meals in Fast Food RestaurantsDokumen9 halamanPatterns of Mobile Device Use by Caregivers and Children During Meals in Fast Food RestaurantsFernandaGuimaraesBelum ada peringkat

- Zen Sushi To Go MenuDokumen0 halamanZen Sushi To Go Menunadia2466Belum ada peringkat

- Role-Play Conversations and Lesson Plans PDFDokumen7 halamanRole-Play Conversations and Lesson Plans PDFLuz HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Gender Base Violence On H&M SupplierDokumen53 halamanGender Base Violence On H&M SupplierLembaga Informasi Perburuhan Sedane (LIPS)100% (1)

- 4 Set Kertas Soalan Bahasa Inggeris PPT 2022 - Tahun 4 03Dokumen13 halaman4 Set Kertas Soalan Bahasa Inggeris PPT 2022 - Tahun 4 03Maria Ahmad MalikeBelum ada peringkat

- RrratherDokumen14 halamanRrratherPeritwinkleBelum ada peringkat

- 05 AAU - Level 4 - Test - Standard - Unit 5Dokumen3 halaman05 AAU - Level 4 - Test - Standard - Unit 5Paz Blasco100% (2)

- Transitional Input VATDokumen21 halamanTransitional Input VATJoanne TolentinoBelum ada peringkat

- Sugarcane Industry: Production, Challenges and Future OutlookDokumen23 halamanSugarcane Industry: Production, Challenges and Future OutlookVivek Kr TiwariiBelum ada peringkat

- AG 201 Properties Biological Materials Food QualityDokumen2 halamanAG 201 Properties Biological Materials Food QualitySonu Lokprakash ChandraBelum ada peringkat

- EO No. 015 - 2018 REORGANIZATION OF BNCDokumen2 halamanEO No. 015 - 2018 REORGANIZATION OF BNCSherrylin Punzalan Ricafort100% (7)

- Middlebay Corporation Case StudyDokumen4 halamanMiddlebay Corporation Case StudyVince KechBelum ada peringkat

- SantaDokumen1 halamanSantaRajesh VermaBelum ada peringkat

- Magicook 20G (Elec) : Downloaded From Manuals Search EngineDokumen20 halamanMagicook 20G (Elec) : Downloaded From Manuals Search EngineNavaneetha Krishnan GBelum ada peringkat

- Boy's Lonely Weekend After Father Abandons Him at the ZooDokumen1 halamanBoy's Lonely Weekend After Father Abandons Him at the ZooSoul Dance ArtsBelum ada peringkat

- Synopsis NavinDokumen11 halamanSynopsis Navinshiv infotechBelum ada peringkat

- Ingles I, Tarea V, PaulaDokumen6 halamanIngles I, Tarea V, PaulaIsaura Concepcion HenriquezBelum ada peringkat

- Examen Final Inglés 4Dokumen14 halamanExamen Final Inglés 4Saito_01100% (1)

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfDari EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (36)

- Workin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherDari EverandWorkin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherBelum ada peringkat

- Those Who Wander: America’s Lost Street KidsDari EverandThose Who Wander: America’s Lost Street KidsPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (19)

- The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationDari EverandThe Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (32)

- Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in CrisisDari EverandHillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in CrisisPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (4276)

- Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in AmericaDari EverandNickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (186)

- High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingDari EverandHigh-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingBelum ada peringkat

- Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global PovertyDari EverandPoor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global PovertyPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (263)

- Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthDari EverandHeartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (269)

- Fucked at Birth: Recalibrating the American Dream for the 2020sDari EverandFucked at Birth: Recalibrating the American Dream for the 2020sPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (173)

- Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaDari EverandNot a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (37)

- The Injustice of Place: Uncovering the Legacy of Poverty in AmericaDari EverandThe Injustice of Place: Uncovering the Legacy of Poverty in AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (2)

- Grace Can Lead Us Home: A Christian Call to End HomelessnessDari EverandGrace Can Lead Us Home: A Christian Call to End HomelessnessBelum ada peringkat

- Charity Detox: What Charity Would Look Like If We Cared About ResultsDari EverandCharity Detox: What Charity Would Look Like If We Cared About ResultsPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (9)

- The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationDari EverandThe Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (19)

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfDari EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (126)

- The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York CityDari EverandThe Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York CityPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (190)

- Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others CollapseDari EverandAlienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others CollapsePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (35)

- The Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityDari EverandThe Meth Lunches: Food and Longing in an American CityPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (5)

- Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthDari EverandHeartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (188)

- Sons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics: Mental Illness and Homelessness in Los AngelesDari EverandSons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics: Mental Illness and Homelessness in Los AngelesBelum ada peringkat

- Downeast: Five Maine Girls and the Unseen Story of Rural AmericaDari EverandDowneast: Five Maine Girls and the Unseen Story of Rural AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (21)