Art and Propaganda

Diunggah oleh

mmineraHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Art and Propaganda

Diunggah oleh

mmineraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

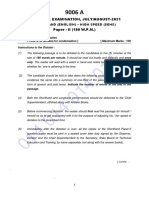

George Orwell The Frontiers of Art and Propaganda I am speaking on literary criticism, and in the world in which we are

actually living that is almost as unpromising as speaking about peace. This is not a peaceful age, and it is not a critical age. In the Europe of the last ten years literary criticism of the older kind criticism that is really judicious, scrupulous, fair-minded, treating a work of art as a thing of value in itself has been ne t door to impossible. If we look back at the English literature of the last ten years not so much at the literature as at the prevailing literary attitude, the thing that strikes us is that it has almost ceased to be aesthetic. !iterature has been swamped by propaganda. I do not mean that all the books written during that period have been bad. "ut the characteristic writers of the time, people like #uden and $pender and %ac&eice, have been didactic, political writers, aesthetically conscious, of course, but more interested in subject-matter than in techni'ue. #nd the most lively criticism has nearly all of it been the work of %ar ist writers, people like (hristopher (audwell and )hilip *enderson and Edward +pward, who look on every book virtually as a political pamphlet and are far more interested in digging out its political and social implications than in its literary 'ualities in the narrow sense. This is all the more striking because it makes a very sharp and sudden contrast with the period immediately before it. The characteristic writers of the nineteen-twenties T. $. Eliot, for instance, E,ra )ound, -irginia .oolf were writers who put the main emphasis on techni'ue. They had their beliefs and prejudices, of course, but they were far more interested in technical innovations than in any moral or meaning or political implication that their work might contain. The best of them all, /ames /oyce, was a technician and very little else, about as near to being a 0pure1 artist as a writer can be. Even 2. *. !awrence, though he was more of a 0writer with a purpose1 than most of the others of his time, had not much of what we should now call social consciousness. #nd though I have narrowed this down to the nineteen-twenties, it had really been the same from about 3456 onwards. Throughout the whole of that period, the notion that form is more important than subject-matter, the notion of 0art for art7s sake1, had been taken for granted. There were writers who disagreed, of course "ernard $haw was one but that was the prevailing outlook. The most important critic of the period, 8eorge $aintsbury, was a very old man in the nineteen-twenties, but he had a powerful influence up to about 3596, and $aintsbury had always firmly upheld the technical attitude to art. *e claimed that he himself could and did judge any book solely on its e ecution, its manner, and was very nearly indifferent to the author7s opinions. &ow, how is one to account for this very sudden change of outlook: #bout the end of the nineteen-twenties you get a book like Edith $itwell7s book on )ope, with a completely frivolous emphasis on techni'ue, treating literature as a sort of embroidery, almost as though words did not have meanings; and only a few years later you get a %ar ist critic like Edward +pward asserting that books can be 0good1 only when they are %ar ist in tendency. In a sense both Edith $itwell and Edward +pward were representative of their period. The 'uestion is why should their outlook be so different: I think one has got to look for the reason in e ternal circumstances. "oth the aesthetic

and the political attitude to literature were produced, or at any rate conditioned by the social atmosphere of a certain period. #nd now that another period has ended for *itler7s attack on )oland in 3595 ended one epoch as surely as the great slump of 3593 ended another one can link back and see more clearly than was possible a few years ago the way in which literary attitudes are affected by e ternal events. # thing that strikes anyone who looks back over the last hundred years is that literary criticism worth bothering about, and the critical attitude towards literature, barely e isted in England between roughly 3496 and 3456. It is not that good books were not produced in that period. $everal of the writers of that time, 2ickens, Thackeray, Trollop and others, will probably be remembered longer than any that have come after them. "ut there are not literary figures in -ictorian England corresponding to <laubert, "audelaire, 8autier and a host of others. .hat now appears to us as aesthetic scrupulousness hardly e isted. To a mid--ictorian English writer, a book was partly something that brought him money and partly a vehicle for preaching sermons. England was changing very rapidly, a new moneyed class had come up on the ruins of the old aristocracy, contact with Europe had been severed, and a long artistic tradition had been broken. The midnineteenth-century English writers were barbarians, even when they happened to be gifted artists, like 2ickens. "ut in the later part of the century contact with Europe was re-established through %atthew #rnold, )ater, =scar .ilde and various others, and the respect for form and techni'ue in literature came back. It is from then that the notion of 0art for art7s sake1 a phrase very much out of fashion, but still, I think, the best available really dates. #nd the reason why it could flourish so long, and be so much taken for granted, was that the whole period between 3456 and 3596 was one of e ceptional comfort and security. It was what we might call the golden afternoon of the capitalist age. Even the 8reat .ar did not really disturb it. The 8reat .ar killed ten million men, but it did not shake the world as this war will shake it and has shaken it already. #lmost every European between 3456 and 3596 lived in the tacit belief that civili,ation would last forever. >ou might be individually fortunate or unfortunate, but you had inside you the feeling that nothing would ever fundamentally change. #nd in that kind of atmosphere intellectual detachment, and also dilettantism, are possible. It is that feeling of continuity, of security, that could make it possible for a critic like $aintsbury, a real old crusted Tory and *igh (hurchman, to be scrupulously fair to books written by men whose political and moral outlook he detested. "ut since 3596 that sense of security has never e isted. *itler and the slump shattered it as the 8reat .ar and even the ?ussian ?evolution had failed to shatter it. The writers who have come up since 3596 have been living in a world in which not only one7s life but one7s whole scheme of values is constantly menaced. In such circumstances detachment is not possible. >ou cannot take a purely aesthetic interest in a disease you are dying from@ you cannot feel dispassionately about a man who is about to cut your throat. In a world in which <ascism and $ocialism were fighting one another, any thinking person had to take sides, and his feelings had to find their way not only into his writing but into his judgements on literature. !iterature had to become political, because anything else would have entailed mental dishonesty. =ne7s attachments and hatreds were too near the surface of consciousness to be ignored. .hat books were about seemed so urgently important that the way they were written seemed almost insignificant.

#nd this period of ten years or so in which literature, even poetry, was mi ed up with pamphleteering, did a great service to literary criticism, because it destroyed the illusion of pure aestheticism. It reminded us that propaganda in some form or other lurks in every book, that every work of art has a meaning and a purpose a political, social and religious purpose that our aesthetic judgements are always coloured by our prejudices and beliefs. It debunked art for art7s sake. "ut it also led for the time being into a blind alley, because it caused countless young writers to try to tie their minds to a political discipline which, if they had stuck to it, would have made mental honesty impossible. The only system of thought open to them at that time was official %ar ism, which demanded a nationalistic loyalty towards ?ussia and forced the writer who called himself a %ar ist to be mi ed up in the dishonesties of power politics. #nd even if that was desirable, the assumptions that these writers built upon were suddenly shattered by the ?usso-8erman )act. /ust as many writers about 3596 had discovered that you cannot really be detached from contemporary events, so many writers about 3595 were discovering that you cannot really sacrifice your intellectual integrity for the sake of a political creed or at least you cannot do so and remain a writer. #esthetic scrupulousness is not enough, but political rectitude is not enough either. The events of the last ten years have left us rather in the air, they have left England for the time being without any discoverable literary trend, but they have helped us to define, better than was possible before, the frontiers of art and propaganda. 35A3

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Artaud in MexicoDokumen7 halamanArtaud in MexicommineraBelum ada peringkat

- Chris Burden and The Limits of ArtDokumen3 halamanChris Burden and The Limits of ArtmmineraBelum ada peringkat

- Discourse On ThinkingDokumen49 halamanDiscourse On Thinkingmminera100% (1)

- A Museum That Is NotDokumen20 halamanA Museum That Is Notmminera100% (1)

- Burger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4Dokumen15 halamanBurger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4monkeys8823Belum ada peringkat

- Daybreak: Thoughts On The Prejudices of Morality - Friedrich NietzscheDokumen295 halamanDaybreak: Thoughts On The Prejudices of Morality - Friedrich Nietzschetaimur_orgBelum ada peringkat

- Burger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4Dokumen15 halamanBurger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4monkeys8823Belum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- CW3 - 3Dokumen2 halamanCW3 - 3Rigel Zabate54% (13)

- Sample Constitution and BylawsDokumen7 halamanSample Constitution and BylawsSummerRain67% (3)

- Personal Laws IIDokumen12 halamanPersonal Laws IIAtulBelum ada peringkat

- Kansas Bill 180 SenateDokumen2 halamanKansas Bill 180 SenateVerónica SilveriBelum ada peringkat

- Maintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsDokumen5 halamanMaintaining momentum and ensuring proper attendance in committee meetingsvamsiBelum ada peringkat

- What Really Happened at Paris The Story of The Peace Conference, 1918-1919 - House, Edward Mandell, 1858-1938 & Seymour, Charles, 1885-1963Dokumen505 halamanWhat Really Happened at Paris The Story of The Peace Conference, 1918-1919 - House, Edward Mandell, 1858-1938 & Seymour, Charles, 1885-1963Anonymous vnTWqRDmLBelum ada peringkat

- Reviewer - PSCI 101 DropboxDokumen1 halamanReviewer - PSCI 101 Dropboxemmanuelcamba100% (1)

- Systematic Voters' Education and Electoral ParticipationDokumen1 halamanSystematic Voters' Education and Electoral ParticipationRenukaBelum ada peringkat

- Artículo InterseccionalidadDokumen6 halamanArtículo InterseccionalidadGabiBelum ada peringkat

- Republic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayDokumen2 halamanRepublic of The Philippines Barangay General Malvar - Ooo-Office of The Punong BarangayBarangay Sagana HappeningsBelum ada peringkat

- Britain's Industrial Revolution and Political Changes in the 18th CenturyDokumen18 halamanBritain's Industrial Revolution and Political Changes in the 18th CenturyCarolina MacariBelum ada peringkat

- Rights of Minorities - A Global PerspectiveDokumen24 halamanRights of Minorities - A Global PerspectiveatreBelum ada peringkat

- Resolved: Unilateral Military Force by The United States Is Not Justified To Prevent Nuclear Proliferation (PRO - Tritium)Dokumen2 halamanResolved: Unilateral Military Force by The United States Is Not Justified To Prevent Nuclear Proliferation (PRO - Tritium)Ann GnaBelum ada peringkat

- Command History 1968 Volume IIDokumen560 halamanCommand History 1968 Volume IIRobert ValeBelum ada peringkat

- Georgii-Hemming Eva and Victor Kvarnhall - Music Listening and Matters of Equality in Music EducationDokumen19 halamanGeorgii-Hemming Eva and Victor Kvarnhall - Music Listening and Matters of Equality in Music EducationRafael Rodrigues da SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Rhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"Dokumen4 halamanRhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"NintengoBelum ada peringkat

- Theme Essay OutlineDokumen7 halamanTheme Essay Outlineafabfoilz100% (1)

- Evolution of Local Self-GovernmentDokumen15 halamanEvolution of Local Self-GovernmentPavan K. TiwariBelum ada peringkat

- History of Policing System PH and UsDokumen5 halamanHistory of Policing System PH and UsMicaella MunozBelum ada peringkat

- Group Discussion ScriptDokumen2 halamanGroup Discussion ScriptHIREN KHMSBelum ada peringkat

- Somalia - Fishing IndustryDokumen3 halamanSomalia - Fishing IndustryAMISOM Public Information ServicesBelum ada peringkat

- NSGB BranchesDokumen4 halamanNSGB BranchesMohamed Abo BakrBelum ada peringkat

- PMS Preparation Knowledge About Scientific Studies of Various FieldsDokumen54 halamanPMS Preparation Knowledge About Scientific Studies of Various Fieldssakin janBelum ada peringkat

- LBP Form No. 4 RecordsDokumen2 halamanLBP Form No. 4 RecordsCharles D. FloresBelum ada peringkat

- Innovative Israel: Joint PMO-Health Ministry StatementDokumen8 halamanInnovative Israel: Joint PMO-Health Ministry StatementLaurentiu VacutBelum ada peringkat

- Stop Sexual HarassmentDokumen12 halamanStop Sexual Harassmentredarmy101100% (2)

- Hangchow Conference Speech on PhilosophyDokumen2 halamanHangchow Conference Speech on PhilosophypresidentBelum ada peringkat

- B19.co v. Hret - DigestDokumen2 halamanB19.co v. Hret - DigestCarla Mae MartinezBelum ada peringkat

- AskHistorians Podcast 092 TranscriptDokumen15 halamanAskHistorians Podcast 092 TranscriptDavid100% (1)

- Site Selection: Pond ConstructionDokumen12 halamanSite Selection: Pond Constructionshuvatheduva123123123Belum ada peringkat