Molloy Manzano

Diunggah oleh

Laura GandolfiHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Molloy Manzano

Diunggah oleh

Laura GandolfiHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

From Serf to Self: The Autobiography of Juan Francisco Manzano Author(s): Sylvia Molloy Source: MLN, Vol.

104, No. 2, Hispanic Issue (Mar., 1989), pp. 393-417 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2905146 . Accessed: 01/03/2011 11:45

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=jhup. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to MLN.

http://www.jstor.org

The Autobiography From Serf to Self:

Manzano ofJuanFrancisco

Sylvia Molloy

"The lady Dofia Beatriz de JustizMarchioness Justizde Santa Ana, wife of Don Juan Manzano, took pleasure everytimeshe went to her famous estate of El Molino in choosing the prettiest Creole girls, when they were ten or eleven years of age; she took themwithher and gave theman education suitable to their class and condition so her house was always filled with servants. ..." ["La Sra. Da. Beatriz de Justiz MarquezaJustiz de Sta. Ana, esposa del Sor. Don Juan Manzano, tenia gusto de cada vez qe. iva a su famosa asienda el Molino de tomar las mas bonitas criollas,cuando eran de dies a onse afios; las traia consigo y dandoles una educaci6n conformea su clase y condision, estaba siempre su casa llena de criadas.. ..'T

' Juan Francisco Manzano, Autobiografia, dejuan Fco. Manzano,with y versos cartas a preliminary studybyJose L. Franco (La Habana: Municipio de La Habana, 1937), syntaxand uncertain p. 33. This edition, unlike others, retains the idiosyncratic spellingof Manzano's originalmanuscriptof 1835. I shall quote fromit,indicating itself. I shall page numbersin parenthesesonlywhen quoting fromtheAutobiografia translate Manzano's toneas best I can, respectingthe run-in constructionof his sentences,his punctuationand the belabored nature of his syntax.I shall not attempt,however,to reproduce his misspellings.This seems to me preferable(and surely fairer to Manzano) than quoting from the much altered, cleaned up and of 1840 published in Poemsbya Slave ideologicallyconditioned English translation fromtheSpanishbyR. R. Madden, Translated Liberated; in theIsland of Cuba, Recently to Which Are by Himself, NegroPoet,Written ofthe EarlyLifeofthe theHistory M.D. with By R.R.M. of Cuban Slaveryand the Slave-Traffic, PrefixedTwo Pieces Descriptive (London: Thomas Ward and Co., 1840). I find it equally inadvisable to translate fromIvan Schulman's modernized edition (Juan Francisco Manzano, Autobiograffa de un esclavo,ed. Ivan A. Schulman [Madrid: Guadarrama, 1975]). I shall discuss these and other manicured versionsof Manzano later on.

394

SYLVIAMOLLOY

This casual anecdotal beginning, not unlike the opening of so novels, is deceptivelyinnocent.For it is many nineteenth-century not, as might appear, the beginning of a novel told by a thirdperson narratorof which the Marquesa is the principalcharacter; of the Marquesa's it is, instead,the beginningof the autobiography slave,Juan Francisco Manzano. Nor, as the Spanish originalclearly in its shows, is it a particularlyharmonious piece: unsystematic in its punctuation,nonchalantin its syntax,this spelling,arbitrary textis, quite obviously,different. Juan With the same carefree syntaxand quirky orthography, Francisco Manzano goes on to narratewhat appears to be the first and only slave narrativepublished in Spanish America. The initial focus on his mistressis elaborated upon in the lines that follow. Manzano tells how, on one of his lady's visitsto El Molino, she chose "one Maria del Pilar Manzano, my mother" (33) for chief handmaid; how Maria del Pilar wet-nursedManuel de Cardenas y Manzano, the Marquesa's grandson; how the handmaid married Toribio de Castro, another of the Marquesa's slaves; and, eventually,as a culminationof this tortuousgenealogy binding the slave to his master,how Maria del Pilar gave birthto a child of her own, As was the Juan Francisco Manzano who writesthe Autobiograftia. the child was not given his father'ssurname but thatof customary, his master.In thisway,the Marquesa's mundane visitto El Molino sallyingforthat five)be(an ironicantecedentof Valery'smarquise gesture: the aged, benevolentprescomes a founding,life-giving ence of Beatriz de Justizmust per forceopen Manzano's lifestory the power that,presidingover life and since she is, quite literally, death, allows him to be born. on a gesturefrom That the slave's life should depend so totally his owner, or that the slave's familyromance should be so enmeshed in that of his master'sis not, of course, unusual in ninecolonial Cuba: "rememberwhen you read me that teenth-century I am a slave and that the slave is a dead being in the eyes of his Domingo Del Monte.2In master,"writesManzano to his protector, dead being in the eyes to that life Manzano brings hisAutobiografia, replaces the mistress' He readers. his not of his masters but of another gesture, with describes it, he founding gesture, even as writing. own effects-his himself he which also life-giving, and written, was this autobiography in which The circumstances

2

p. 84. Letterof 25 June 1835, in Autobiografia,

M L N

395

the fortuneof the text thereafter, are of singular interest.As a domestic cityslave who taught himselfto read and writeagainst remarkableodds (I shall return to this issue, quite central to my discussion),Manzano standsout amongsthis peers. A poet of some renown,his slave statusnotwithstanding, he became in the 1830's the protege of the reformistalthough not openly abolitionist Cuban intellectualswho gathered around the liberal writerand publicist,Domingo Del Monte, and he was encouraged in his literary ventures by that group. One result of these contacts was Manzano's freedom; taking up a collection, Del Monte and his friends obtained his manumissionin 1836. Manzano's autobiography was another: at Del Monte's request, in order to publicize the cause of abolitionabroad, Manzano wrotea two-part autobiography narratinghis miserable life as a slave. The text was to be included in a dossier that Del Monte was compiling for Richard Madden, the Britishmagistratewho, as superintendantof liberated Africans, served as arbiterin the Court of Mixed Commission established in Havana in 1835.3 Once completed, Manzano's life storywas correctedand edited by a memberof Del Monte's group, Anselmo Suarez y Romero, himselfthe author of an abolitionist novel, Francisco, which was also to be part of the Del Monte antislavery dossier. Manzano's text was translated into English by Madden (not so Suarez y Romero's Francisco)and presented, toConventionheld getherwitha report,at the General Anti-Slavery in London in 1840. In Cuba, Manzano's manuscript(which remained the propertyof Domingo Del Monte) circulatedclandestinely in del Monte's milieu, to the point that "when someone understood thathe mentions'the autobiography'it is immediately speaks of Manzano's."4 Thanks to the occasional slackeningof censeveralfragsorshiplaws, FranciscoCalcagno was able to integrate ments of the text in his Poetas de color,a series of biographies of Black poets, but the entireautobiographywas considered unpubaccount of the tumultuousrelationsbetweenEn3For a concise and informative see FranklinW. Knight, gland and Spain (and hence Cuba) on the issue of slavery, the Nineteenth Century (Madison, Milwaukee and London: Slave Society in Cuba during of Wisconsin Press, 1970), especially Chapter III: "The Cuban Slave University Trade, 1838-1865." For an overall vision of slaveryin Cuba, referenceto Manuel Complexof Sugar in Cuba. Moreno Fraginals, The Sugarmill. The Socioeconomic 1760-1860 (New York and London: MonthlyReviewPress, 1976), is indispensable. 4 Francisco Calcagno, Poetasde color. 4th ed. (Havana: Imprenta Mercantilde los Herederos de Santiago Spencer, 1887), p. 64, note 1. This and all othertranslations are mine, unless otherwiseindicated.

396

SYLVIAMOLLOY

lishable,for politicalreasons, at least until 1898. By then,it was all Manzano's Virtuallyunknownfor nearlya century, but forgotten. manuscriptpassed on to Del Monte's heirs and was fifty-two-page eventuallyacquired by the Biblioteca Nacional in Havana; it was published for the firsttime in its entiretyin 1937. Until then, Madden's somewhat special English translationwas the only version of Manzano's autobiographyavailable to the general reader. was As maybe seen fromthisaccount,Manzano's autobiography an inordinatelymanipulated text-a slave narrativethat,besides having dispossession for its subject, was, in its very composition at the request of anand publication,dispossessed. It was written other (Del Monte); it was correctedand edited by another (Suarez y Romero); it was translatedand altered by another (Madden); it was integratedinto another's text (Calcagno). It was, in short,a textused by others over which Manzano had, apparently,littleor cause, one a worthy no control.That the textwas used to further close to Manzano's heart, does not lessen the importanceof that manipulation. Manipulationof one kind or another is a frequentenough phenomenon, of course, in North American slave narratives. The then discussed with the slave's storywas usually told orally first, editor,then dictatedto thateditor,who would then read it back to textwould The transcribed for clarification. its originalstoryteller to supportit and, of thenbe complementedwithother testimonies course, to condition its reception.5 As often as not, the-editors to the text pronouncements would add factualdetailsor rhetorical

5 See John W. Blassingame's introductionto his edition of Slave Testimony. Two and Autobiographies (Baton Rouge: Louisiana Interviews, Speeches, Centuries ofLetters, Press, 1977): University

Generallythe formerslave lived in the same locale as the editor and had given oral accounts of his bondage. If the fugitivebelieved that the white man truly of publishinghis account. Once respected blacks,theydiscussed the advisability the the white man persuaded the black to record his experiences for posterity, dictationmightbe completedin a fewweeksor be spread over twoor threeyears. asking for elaboration of certain Often the editor read the storyto the fugitive, details. When the dictaof confusingand contradictory points and clarification compiled appendices to corroboratethe narration ended, the editor frequently tive. The appendices consisted almost entirely of evidence obtained from churches,and courts,governors, reportsof legislatures, southernsources: official by southernwhitesor newspapers edited by agriculturalsocieties,books written them. If those among the editor's friendswho firstheard the storydoubted its for hours. (p. xxii) the fugitive theysometimesinterrogated authenticity,

M L N

397

so as to enhance its dramatic effect.6This creative and wellsince, as John Blassinmeaning editingwas not withoutits pitfalls game points out, "on occasion the narrativescontain so many of of the the editors'views that there is littleroom for the testimony fugitive."7 At the time he composes Manzano's case is obviouslydifferent. wella relatively he is (besides being a slave) a writer, his lifestory, established poet, and would not seem to need, as did so many North American slaves, the mediation of a white scribe to give shape to words he himselfcould only speak. Yet Manzano does but need the whiteman's mediation-not forhis textto be written are worksin collaboraslave narratives forit to be read. Inevitably, to plead against tion since,on his own, the slave lacks the authority his condition; his textmustbe incorporatedinto the whiteliterary (and thusvalidatedby it) ifit is to be heeded at all. It establishment is always,in one form or another,a mediated text,one unavoidhave describedand the twoness so manyblack writers ably fostering have felt.In Manzano's case, the so many membersof minorities two principal mediators were Del Monte and Madden, the instiin Manzano needs now to whose interest gator and the translator, be considered in detail. mentorfor Manzano well Del Monte played the role of literary before the autobiographical project, when Manzano was writing poetry.This was not an exceptional role for him,and his magistewho sought rial influence was recognized by many young writers his guidance. Even so, Manzano's reaction to Del Monte's reception of his poems seems excessive. His lettersreveal unconditional faith in the critic'sliteraryopinion, unending gratitude for his help, and a near total reliance on Del Monte that amounts to grantinghim absolute power over the poems:

6 Accordingto Blassingame,these transcribed were not high on the list narratives who much preferredBlacks to lectureabout their held by abolitionists, of priorities lives and thus reach a wider audience:

of former on the written narratives low priority placed a relatively [Abolitionists] preferredto base his indictments slaves as propaganda. Generallythe abolitionist of slaveryon the writingsof southern whites.... The main propaganda role played by blacks in the abolition movementwas as lecturers.... [A]ntislavery societiespublished less than 20 percentof the antebellumblack autobiographies. few reviewsof the slave narrativesin abolitionist There were also comparatively journals. (Blassingame, p. xxix) 7 Blassingame, p. xxviii.

398

MOLLOY SYLVIA

to polishing himself which Onlythecarewith Your Gracehas devoted will themin thosepartswhereit was necessary, improving myverses, compositions grantme the titleof 'halfpoet.' I have a fewamatory thetruth ifdidactic or descriptive, a poemI don'tknow amongst them muto a young dedicated to thosethings, is itbearssomeresemblance to tosendthem at thepiano.To D. at thepiano.I wanted woman latto you;butI don'tknowwhatYour Gracewilldecide;on thepoemsthat to disposeof them.8 in yourpowerI awaityourorders are currently Del Monte assumes the power given him by Manzano. Besides dispensing literaryadvice and editing Manzano's poems, he arranges for their publication,in Cuba and abroad.9 He also has and read his poems out loud. (Critics Manzano attend his tertulia have isolated one such reading, turningit into a memorable emblematic fiction-Manzano, reading his sonnet, "My Thirty who Years," before an audience of compassionate delmontinos starta collectionto buy his freedom.) It is quite possible promptly that Manzano played up the dependent nature of his relationship with Del Monte in the hopes of gaining the criticto a cause far Not cointhan the literary qualityof his writing.'0 more important in his letterof 11 December 1834 to Del Monte, after cidentally, quoting from one of his poems where he compares himselfto a leaf, lost in the wind, and Del Monte to a powerfultree,Manzano places not only his poems but his libertyin the hands of his "inremindinghim of "the inclinationto gain comparable protector," his freedom that,by natural principle,is in everyslave.""1 In a sense, both men had somethingto gain from each other; Manzano, both as a slave and as a poet, forreasons thatare self-evident; his patron,for reasons somewhatmore complex. It is clear that for Del Monte, who held liberal views on slaverybut was capable, when he felt threatened,of obfuscated reactions against

p. 79. Letterof 16 October 1834, in Juan Francisco Manzano, Autobiografia, 9 Letterof 11 December 1834, Autobiografia, p. 80. 10"He realizes thathis poetry,whateveritsvalue, mustpass throughDel Monte's hands if it is to reach Europe. He suspectsthathis freedom,if he is ever to attainit, willalso come, in one way or another,fromthose hands." (Roberto Friol,Suitepara Manzano [La Habana, EditorialArte y Literatura,1977], p. 60) Juan Francisco Manzano may have exaggerated his devotion to Del Monte, yet his loyaltywas in favor of Del Monte nonetheless real. This was made evident in his testimony followingthe Conspiraci6n de la Escalera in 1843. during the cruel investigation 11Letter of 11 December 1834, Autobiografia, p. 81. In another letter,dated 25 Del Monte of his wedding (to a freewoman) and February 1835, Manzano informs bringsup, once more, the subjectof his freedom: "Let not Your Grace forgetthat p. 83. J.F. will not be happy if he is not F. and now more than ever." Autobiografka,

8

M L N

399

Blacks,'2 the patientand submissiveManzano (whose patience and fit submissionmay have been strategical as well as temperamental) his expectations; Manzano became for him, as Richard Jackson puts it, somewhatof "a showpiece Black."''3As such, he could in12 No textis more eloquent, in thisrespect,than the open letter Del Monte writes, in August 1844, while in exile in Paris, to the editorof Le Globe.The main thrust of the letteris to defend himself againstthe "calumnies"of those who would implicate him in the 1843 Escalera conspiracy,the thwartedBlack uprisingagainst Spanish authorities.The letter is a remarkable mixture of realisticthinking,ideological straight-jacketing and irrationalfear. Del Monte firmly reasserts his wishto abolish slaverybut then extends his wish to include the banishmentof Blacks ("one of the most backward races in the human family")from the island, so that Cuba may become "the most brilliant beacon of civilization of the Caucasian race in the Spanish American world." The way in whichDel Monte describesthe conspirators' plans is revealing:

Sufficeit to recall what the plan of the conspiracywas, according to depositions made by the Blacks themselves.In the final analysis,this plan amounted to the destruction, by fire,of sugar millsand other countryestates,and to the destruction, by knife and poison, of all white men, so as to take pleasure in their daughters and theirwives withimpunity and then establisha Black republic on the island, like the one in Haiti, under England's protectorate."(Domingo Del T. I. Ed. Jose A. Ferndndez de Castro. [Havana: Colecci6n de Monte, Escritos. Libros Cubanos, Editorial Cultural,S.A., 1929], pp. 189-202) At the beginning of this letter,Del Monte had denied his involvementin the him were extractedfromthe conspiracy,arguing that the depositions implicating Black conspiratorsunder duress. Ironically,in the paragraph quoted above, he resortsto those same depositions as truthful sources withoutmaking the same allowances. 13 "The standard imposed by the Del Monte group, which was more reformist in the depictionof the black than abolitionist, called for 'moderationand restraint' slave.... Since Del Monte knew he had a showpiece Black witha good image and intellectualcapacity,why not display him?" (Richard L. Jackson,"Slavery,Racism and Autobiographyin Two Early Black Writers:Juan Francisco Manzano and in Martin Moria Delgado" in William Luis ed. Voices fromUnder.Black Narrative Latin Americanand the Caribbean [Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984], pp. of slaves forabolitionist 56-57). For otherexamples of the typification purposes, see Larry Gara, "The ProfessionalFugitive in the AbolitionistMovement,"Wisconsin xlviii(1965), pp. 196-204. Magazine ofHistory, Ivan Schulman observes,for his part,thatthe ideal of the Del Monte group was the negroracionalor the criada de raz6n (incidentally, an expression that Manzano of society, "victim uses to describehis mother),a reasonable,non-rebellious unlikely defended the to alienate the conservative elementsof the sacarocracythatstaunchly de ser tiranizadoo correr el riesgo principle of the slave's tyrannization-tiranizar and the continuationof the illegal slave trade. The resultantpatheticbeing would, it was hoped, not only win convertsto the criollo's humanitariancause, but also court the mercyand justice of foreignreaders,especiallythe English,who, in turn, mightbring pressure to bear on the Spanish crown to enforce the slave treaties." (Ivan A. Schulman, "The Portraitof the Slave: Ideology and Aestheticsin the PerCuban Antislavery Novel," in Vera Rubin and ArthurTuden, eds. Comparative on Slavery in New World spectives Plantation Societies [New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1977], p. 359).

400

SYLVIAMOLLOY

thatwould be deed be counted upon to produce an autobiography doubly useful; useful because it would depict the heinous excesses because it would reflect of slavery;and useful, most importantly, the opinion of an enthrough the slave's testimony) (vicariously, lightened middle class that wished to distinguishitselffrom its more obtuse contemporaries.The dossier containing Manzano's autobiographythatDel Monte was to give Madden was destinedto with"the exact stateof opinion on furnishthe English magistrate the slave trade and on the conditionof slaves held by the thinking youthof thiscountry."'14 It is unclear (and of course impossibleto evaluate) to what point Manzano deliberately conformed to Del Monte's ideology. Jackson's contentionthat,in order to please his protector,Manzano "had to play down the threateningimage of the rebellious slave while playing up the image of the docile and submissive slave," while not impossible,has littleto ground it.15Equally plausible (although undoubtedly more bleak) is the conjecture that image of the Manzano did not have to play down the "threatening rebellious slave," simplybecause he did not have one: the system had perverselybeaten it out of him, both throughphysicalabuse of privilege. In through the attribution and, more importantly, becomes second nature; of oppressive situations,self-censorship the images the systemhad to offer,Del Monte's ideal probably seemed the most desirable to Manzano and it may well have coinwithhis self-image. cided, withouttoo much conflict, Only Manzano's lettersremain of the correspondence between Manzano and Del Monte, so that whatever writteninjunctions Manwere given by Del Monte, if any, are missing.Furthermore, he mighthave rezano's lettersdo not refer to any instructions ceived fromDel Monte, nor does he provide detailsabout what he He calls his project "the course of mylife"or "the story is writing. of mylife,"and, quite often,referscautiouslyto his autobiographen Cuba, citedin CUsarLeante, "Dos 14 Jose Z. Gonzalez del Valle, La vida literaria 207 (July-August1976), p. obras antiesclavistascubanas," Cuadernosamericanos, 175. '5Jackson, p. 56. Jackson's conjecturingdoes not stop here. Concluding, from (the only one thatremains),that Manzano the end of part one of the Autobiografia was in the process of shedding his submissiveimage, Jackson speculates on why part two went astray: "[W]e can assume that part 2 could well have been franker than part I. Perhaps Manzano in part 2 forgotthe original guidelines and expressed some views that, for all concerned including Manzano, were betterleft and wanted to go faster unsaid. Perhaps Manzano had tired of being circumspect and fartherthan his liberal whitefriendswere prepared to go." (p. 58).

M L N

401

he uses the ical venture as "the matter,"el asunto; significantly, same euphemism to refer to the plans for his manumission, and freedomwere closelyallied in his mind. showinghow writing

What Manzano's letters do reveal, however, is a change of attitude, effected by the autobiographical experience itself. Two letters referring specifically to the project allow one to measure that change. In the first, dated 25 June 1835, Manzano describes the actual beginning of his writing. I quote it in its near entirety for it is of consequence: My dear Sir Don Domingo: I received Your Grace's esteemed letterof of this month and I was surprised that in it Your Grace the fifteenth I can't tellsme thatthreeor fourmonthsago he asked me forthe story, but answer that I did not receive notice so far in advance, for the very to lookingover the day thatI received your letterof the 22 I set myself space occupied by the course of my life,and when I was able to I set myself to writing believing that a real's worth of paper would be on withoutstopping,even when skippingat enough, but havingwritten timesfour,and even fiveyears,I have stillnot reached 1820, but I hope events;on more than to the mostinteresting myself to end soon limiting four occasions, I was close to givingup, a picture filledwithso many de protocols calamities seems but a bulky chronicle of lies [un abultado all the more so since froma veryyoung age cruel lashings embusterias], made me aware of myhumble condition;I am ashamed to tellthis,and I don't know how to demonstratethe factsif I leave the worstpart out, and I wish I had other factsto fillup the storyof my life withoutrecalling the excessive rigor withwhich my formermistresstreated me, need to resortto a risky thus obligingor pushing me into the forceful escape to save my miserable body from the continuous mortifications that I could no longer endure, so prepare yourselfto see a weak creain the greatestsufferings, going fromoverseer to overture stumbling seer, without ever receiving praise and being always the target of I fearlosingyouresteema hundred percent,but let Your Grace misery, rememberwhen he reads me that I am a slave and that the slave is a dead being in the eyes of his master,and do not lose sightof what I and you will find that the endless have gained. Consider me a martyr lashings that mutilatedmy stillunformedbody will never make a bad in your characteristic pruman of your devoted servantwho, trusting and thiswhen the one dence, now dares breathea word on thismatter, who has caused me such miseryis stillalive.'6 The awkward syntax of this letter, which I have attempted to

16 Autobiografia, pp. 83-84. The person alluded to at the end of the letterwas the Marquesa de Prado Ameno, who died in 1853, a year before Manzano. (Friol, p. 51).

402

SYLVIAMOLLOY

reproduce in English,'7 is typicalof Manzano's prose. It lends a to itscomcontributing effectively sense of urgencyto his writing, pelling quality. Manzano needed littleencouragement to tell his was another matter. story.How to tell it, as this letterillustrates, access to a new scene of For Manzano, the autobiographysignifies safe fromthe relatively withanxiety, verydifferent writing fraught scene to which he was accustomed as a derivativepoet. The quesintions he asks himselfin this letter,the reflectionsself-writing spires, the misgivings he experiences are all part of the autobiographer'squandary. What shall I choose to tell?When shall I stop? Will theythinkI'm lying?And then,as the "bulkychronicleof lies" is out in the open beforehim,come the fears: I am ashamed of it; I wish I had other things to tell besides it; it will disappoint my reader (Del Monte) who will no longer like me. What is Manzano ashamed of, what is the nature of the it that disturbshim to the point of shame? If it is the miseryand torture to which he has been subjected, why should he be ashamed and whywould it not his oppressors? If it is the tellingof thatmisery, disappoint Del Monte when he had requested the piece? These ambiguitiesare not resolved but enhanced by the contradictory nature of some of Manzano's queries. On the one hand, he dehimselfto the "most interesting" events; clares that he is limiting factsthan those he is on the other,he wishes thattherewere other tellingto fillup the storyof his life.A second letterto Del Monte, writtenthree monthslater on 29 September 1835, is remarkably different. Again Manzano bringsup the asunto,but gone are the reactionto his mentor's anxietyand disarraythatmarked his first the syntaxless request. Even the manner of the letteris different, choppy,the tone more poised. Again, forpurposes of comparison, I quote extensively: to write downforYour Gracea partof the [I] have preparedmyself ofmylife, itsmost interesting events ofitmine history reserving [istoria] ofmycountry, at seatedin somecorner [demiella]forsomedaywhen, I maywrite a truly peace, assuredof myfateand of mylivelihood, itis bestnotto givethis thespecCubannovel.For themoment matter occurrences and scenesbetacular development required bydifferent

17 See, for example, the English translation of thissame letterin Juan Francisco Manzano, TheLifeand Poens ofa CubanSlave. Edward J. Mullen, ed. (Hamden, CT: Archon Book, 1981) pp. 14-15. Much like Madden, the editor chooses to render in "correct"English. I disagree withhis choice and shall elaborate Manzano's letters later on mydisagreement.

M L N

403

cause one would need a whole volume,but in spite of thatYour Grace will not lack material,tomorrowI shall begin to steal hours frommy sleep for thatpurpose. I saw Doctor Don Dionisio by chance on the street,I spoke to him thathe would not forget about thismatterand he told me not to worry, me because he wanted Europeans to see thathe was rightto speak of a slave who had served in his house, a poet whose verses he recited by by one withouteducaheart and some doubted that theywere written tion,and thathe would writeto Your Grace as soon as he could.'8 Manzano's attitude in this letter could not differ more from that of the previous one. Instead of queries and doubts, now there are decisions; Manzano speaks as the author of his text, in control of his writing,well aware of the fictional potential of his material. (He even reminds the recipient of his letter, in an oblique way, of his fame as a poet: white men know his texts by heart.) While the first letter gave full power to Del Monte over Manzano's story, the second establishes a line between what has been promised to the critic ("you will not lack your material") and what Manzano keeps for himself. The previous letter, marked by subservience, waived Manzano's rights to the text by "giving" it to Del Monte; the second letter, marked instead by resistence, has Manzano keep the text for himself. Or rather, has him keep part of the text.

that In addition, the second letterreversesthe notion of interest justifies the choice of material for the autobiography. In June, events" for Del Manzano was writingdown "the most interesting events" Monte; in Septemberhe is reserving"the most interesting foran eventual book he willwritewhen he is freeand forhimself, feels fullyat home. Now thisdoes not mean, of course, that Manevents rezano, in September,is removingthose most interesting less them with other, corded in June from his text and replacing I find imporof capital and this does mean, ones. It interesting tance, that in these three monthsof writinghimselfdown, Manhas changed; that he is zano's concept of "the most interesting" else in himselfbesides the storyof his misforvaluing something elseis not forgiving. something tunes,and thatthatmostinteresting

18 Autobiografia, to pp. 84-85. Dissatisfiedwithhis masters,Manzano was trying change houses ("the freedom I had been promised in this house seems to have dissipatedin the wind togetherwiththe word",p. 85) and Dionisio Mantilla,whose Manzano had served,had promisedto help him. AlthoughDionisio Mantilla family was unable to do so, he was active in collectingmoney to buy Manzano's freedom (see letterof 16 October 1835, p. 86).

404

SYLVIAMOLLOY

Since Manzano never wrote his "Cuban novel" (indeed he did not writemuch afterthe Autobiografia, save some poems'9) he did not endow thatsomethingelse witha visibleform.My contention is thatthatsomethingelse is nonethelessthere,markingthe entire autobiography, fromthe momentresistance to the other (or differentiationfromthe other) replaces capitulationbefore the other. I would argue that, from the moment Manzano announces that there is a part of himselfhe will not cede-a part thatis ungiving -that part informs, throughitsverydefiantsilence,the restof the writing. A look at Richard Madden's translation of Manzano's text,and, more precisely, a comparison of that English version with the Spanish original,is useful at this point. Indeed, by workingfrom Madden's text back to Manzano's, assessing the changes made by Madden and, more importantly, evaluating what Madden suppressed from the original because it in some way frustrated readers' expectations,one can begin to identify the nodules of resistance in Manzano's story.After undertakingpreciselysuch a Edward comparison in his 1981 edition of Madden's translation, Mullen pays scant attentionto the differencesbetween the two texts.While notingthatthereare suppressionsand a fewchanges, he surprisingly concludes that "Madden's translation is-with the exceptions noted-strictly that, a rendition into English of the authored text".20 The statement is highly original,. . . of an originally debatable, given the factthatone of the first thingsMadden does is, precisely, to "unauthorize"the textby makingit anonymous.It

19Much has been made of thispurported "silence" of Manzano whichhas often been attributed mythical overtones.Sudrez y Romero speciouslyargues that"itwas as a slave that he learned to read and write,as a slave that he composed his first poems, as a slave that he sketchedthe disturbing account of his troubled life,as a slave that he struckup friendshipswith the intellectuals who redeemed him.... [H]owever, as if pain were his only inspiration, Juan Francisco Manzano became silentwhen the nightof serfdomgave way to the dawn of freedom." (Quoted in Antonio L6pez Prieto,Parnasocubano.Colecci6n depoesiasselectas de autores I cubanos. [Havana: Editorial Miguel de Villa, 1881], p. 253) By carefullytrackingdown poems by Manzano that were published in periodicals afterhis manumission,Roberto Friol successfully challenges thismythand restoresManzano's "silence" to its true proportions.(Friol, pp. 215-6) 20 Mullen in Juan Francisco Manzano, TheLifeand Poemsofa Cuban Slave, p. 22. My emphasis. Several pages earlier,Mullen's criticalassessmentseemed to point in the opposite way: "Another plausible explanation [for the difference between Madden's text and Manzano's] would be that Madden's translationis in realitya reconstruction of the Spanish originaldesigned to reflectabolitionist views,which would explain whythe texthighlights in particularthe degradationsof slavery"(p. 13).

M L N

405

becomes, to quote the title,The Life and Poemsof a Cuban Slave. Madden's claimsthatthiswas done to protectManzano, whilemost probablysincere,are not completelyconvincing.For, as has been disappeared from the argued, if Manzano's name has effectively titlepage, his initialsappear in a quotation from Del Monte conMadden furnishesdetained in Madden's preface. Furthermore, tails from Manzano's life (how much it cost to liberate him, what trades he plied as a free man2l) thatmake him easily identifiable: him simplybecause they did not identify "The Spanish authorities did not wish to. At thattime,the only poet on the island thathad instead,that once been a slave was Manzano."22It is highlylikely, Madden needed to make the textanonymousin order to heighten was Thus his translation whathe considered itsrepresentativeness. presentednot as the life storyof one individualbut as the generic as "the account of "the Cuban slave" and, even more ambitiously, most perfectpictureof Cuban slaveryever given to the world."23 that led Madden to the excision The claim for representativeness of the particular(the amputationof the name; the cuts thatwould follow)tellsus as much about Madden and his practiceof reading as it does about the generic Cuban slave.24 In a more general cast upon certaintexts manner, thisburden of representativeness

21 "He was about thirty-eight The price yearsof age when he obtained his liberty. as a tailorforsome timeafter paid forit was 800 dollars. He obtained employment he went out to service-then tried the business he got his freedom,subsequently, and was not successful-was advised to set up as a confectioner, of a house-painter, settleddown as a 'chefde cuisine' and lost all his moneyin thatline,and eventually, in occasional service."(Madden, in Manzano, TheLifeand Poemsofa Cuban Slave, p. 39) seems to have been less 22 Friol, p. 34. For non-Cuban readers, identification easy: "Since Madden did not publish Manzano's full name in his translation,a number of American writers,among them Amelia E. Barr and William Wells mulattopoet, Pldcido (Gabriel de Brown,confused Manzano withthe better-known la Concepti6n Valdes, 1809-44), producingcurious hybridbiographicalsketchesof (Mullen, in Manzano, TheLifeand Poemsofa Cuban Slave, p. 12) the writers." 23 Madden, in Manzano, TheLifeand Poemsofa Cuban Slave, p. 39. 24 A similarmanipulationof the text,fromthe individualto the general, may be de un esclavo Autobiograffa of Manzano's autobiography, seen in Schulman's retitling de un cimarr6n, published to consid(an echo, perhaps, of Miguel Barnet'sBiografta words,the non erable acclaim a fewyearsearlier). Indeed, Schulman's preliminary confirmthis shifttowards the sequitur of the second sentence notwithstanding, general:

[W]e decided not to reproduce the textof Franco's edition,whichduplicates the deficiencies thatmake and syntactic withall the orthographic originalmanuscript it so hard to read. We believe that the contemporaryreader, more than ever underdevelopmentand cultural slavery, in mattersof Black literature, interested dependency, requires a text both reliable and modern. (Juan Francisco Mande un esclavo, p. 10) zano, Autobiografia

406

SYLVIA MOLLOY

by individuals is indicativeof the way in whichthose texts,written from groups judged weaker or insignificantby the group in power, are oftenread. In such cases, neitherthe autobiographers, nor the personas theycreate,are easilyaccepted as individualsby a reading communitywho much prefersto perceive differenceen bloc.This imperativeexerted on some autobiographicaltexts-a wayof puttingitsauthor in his or her place-may be also observed in the way women's autobiographiesare veryoftenread. Madden not only made the textanonymous,he incorporatedit into a book most of whose sections he had writtenhimself.The order of Madden's book is as follows:two long poems by Madden denouncing slavery, "The Slave-Trade Merchant," and "The by HimSugar Estate;"25then the "Life of the Negro Poet Written self" in a much abridged form; then a few "Poems, Writtenin a Slaveryby Juan. .. ," adapted into English by Madden; finally, quite lengthy appendix containing a conversation between Madden and "Sefor . . ." (Domingo Del Monte) and sundrypieces against the slave trade, again writtenby Madden. Despite the of the to the slave,onlyabout a fourth callingattention book's title, and the slave been written himself, total text have by pages of the although well-meaning, doubtlessly Madden's dwarfed by theyare and concludingmaterial. prefatory somewhatstifling, As I mentioned, there are other cuts in Madden's translation besides the supression of Manzano's name.26 Family names are often omitted,as are place names and dates. The order of some incidents is altered, perhaps, as William Luis persuasively sugas a continuumof growing to presentManzano's suffering gests,27 intensity and not, as does the textin Spanish, as an accumulation of brutal incidents interspersed with unexpected moments of

25 The factthatthe titlepage of the book announced the slave's poems in the first place, possiblyled Philip Foner (afterwhat musthave been a veryhastyreading) to ofCuba andIts these twoopening poems by Madden to Manzano. (A History attribute I [New York: International Publishers,1962], p. 192). States, with theUnited Relations When Foner's book was translated into Spanish, the Cuban translators(after a search forthe reading thatmust have been equally hasty),embarked on a fruitless Spanish "originals"of these two poems. (Friol, 33) 26 The suggestionmade by Mullen (Manzano, TheLifeand Poemsofa CubanSlave, draftthatwas shorter froma first p. 13) thatMadden mighthave been translating than Manzano's finalversion-so thatit would not have been he who cut,but Manzano who added-is not veryconvincing.The excised sections,for one reason or piece and it is easy to see why abolitionist another,are all atypicalof a "traditional" Madden would have suppressed them. 27 WilliamLuis, Literary of (Austin: University in CubanNarrative Bondage:Slavery publication) Texas Press, forthcoming

M L N

407

peace and happiness. To have leftthese momentsin place, argues Luis, would have lessened the effect Madden strived for, sugwere mitigatedby momentsof gestingthatthe slave's misfortunes happiness or, at least, relief.Whateverthe reasons for this reordoes a disserviceto the very cause Madden dering, it ultimately of events,whileeffectively presentation linear preached. His more in the slave's life,sacof suffering nature the progressive stressing no less fearful-its arbitraririficesanother of its characteristics, ness. By alternatingrandom momentsof crueltywith no less erto perratic momentsof kindness,Manzano's original highlights fectionthe utterhelplessnessof the slave, a pawn in the hands of his master. Positivemomentsare downplayed,displaced or even suppressed in the English version. Other suppressions affectpassages that image victim" musthave been perceivedas harmfulto the "worthy Manzano's ambiguous desired for Manzano; passages illustrating stance with respect to other Blacks, his confused sense of alleFor example, of his twoness. giance, the dubious manifestations Madden edits out Manzano's self-presentation as "a mulatto amongstblacks" (p. 68). He deletes a passing comparisonof Manzano to Christ(replacingit withthe phrase "like a criminal")in the descriptionof one of his punishments(p. 52), he does away with the passage where Manzano speaks, with some smugness,of his status as head servantand of the way in which he was set as an example beforethe otherslaves,sparkingtheirenvy(p. 59-60). He even eliminates an episode in which Manzano is "dangerously by a black" wounded" in the head by a stone "thrownaccidentally (p. 42). Finally,Madden omitsthe sin querer]. [mela dio un moreno passage in whichManzano, enthusiastic (and not verysympathetic) long period in whichthe capricious Marevokingan exceptionally quesa de Prado Ameno did not make him the victimof her ire, the past and I loved her speaks of her fondly:"[I] had forgotten like a mother,I did not like to hear the other servantscalling her names and I would have accused many of them to her had I not known thatshe got angryat those who carried tales." (p. 68). These editorial deletions, followinga definiteideological patMore revealing are tern, are not, however, the most interesting. otherpassages suppressed by Madden, thosedealing more directly withManzano's person-his urges, his appetites-eliminated for reasons one can only guess. Probably judged insignificant,as having no direct bearing on the exemplary storyof the "Cuban slave," perhaps even considered frivolousby the somewhat staid

408

SYLVIAMOLLOY

of Madden, theyare, on the contrary, crucialto the understanding Manzano the man and Manzano the autobiographerin his complex relationto writing and books. Manzano's autobiographyabounds in referencesto the body, whichis not surprising, giventhe amount of physicalabuse his text describes. For Manzano, the slave, the body is a formof memory, the unerasable reminder of past affronts:"These scars are perin spite of the twenty four years that have petual [estanperpetual passed over them."(p. 54) Yet thatbody does not belong to him; it is his master's to exploit, through hard labor, and it is also the master'sto manipulate,for his pleasure. From earlychildhood on, Manzano's body is not so much exploited through hard work (a he is cityhouse slave, he is onlyoverworkedwhen,in punishment, misHis first sent to the sugar mill) as it is used by his mistresses. who has the tress,the kind and grandmotherly Marquesa de Justiz, child christenedin her own daughter'schristening robes,"took me and theysay I was more in her arms than in fora sortof plaything, a littleCreole whom my mother'swho . . . had given her mistress more comshe called the child of her old age." (p. 34) Infinitely of his second plex but equally depersonalizingis the involvement mistress,the perfidious Marquesa de Prado Ameno, with Man"I was an obzano's body. As his mistress's page, Manzano writes, or littlemulattoof the Marquesa." (p. 61) ject known as the chinito Emblematic of her power over his body is an intricateritual of dress. Madden's translationreduces to three lines the following detailed descriptionof Manzano's first livery: undergar[T]heymade me manystriped shortsuitsand somewhite forwhenI woremypage'slivery, forholments [alguna ropita blanca] in of finecloth, trimmed idaysI was dressedin widescarlet trousers withthe same,a a collartrimmed gold braid,a short jacket without blackvelvet with and on thetiptwolittle cap also trimmed redfeathers in the Frenchstyle and a diamondpin and with all thisand the rings the I hadledin the restI soon forgot secluded life past.... She dressedme I not the combedme and tookcare that mix with other little Blacks (p. 37, myemphasis). For Manzano, clothing provides a new identitywhile effacing the old.28It makes and unmakes the man at random,conferring a

28 "Clothing is that through which the human body becomes significant and thereforea carrier of signs, even of its own signs." (Roland Barthes, "Encore le corps," Critique, 423-424 [1982], p. 647)

M L N

409

tenuous sense of selfhood (a sense that is reinforcedby isolation fromhis peers29)thatis all too easilydestroyed.If Manzano's years in the Marquesa de Prado Ameno's service are presented as an oscillation between good and evil depending on the mistress's whims,no less important is the alternation betweenthe two forms of dress that the text so painstakingly details. On the one hand, there is the ropafina, the finerythat clothes his body inside the house and signals,to him and to others,thathe is in his mistress's good graces. On the other,there is the fall fromgrace, the shorn hair,the bare feetand the esquifacionor fieldlaborer'shemp gown Manzano is forcedinto beforebeing tied up and carriedoffto the sugar mill.30 This change of dress was public,and one was stripped of one's identity in the presence of others; Manzano cleverlyenhances thishumiliation by recordingthe horrorand disbeliefin his littlebrother'seyes when watchingthe scene for the firsttime (p. 46). As Manzano writeseloquently,"the change of clothes and of fortunewere one." (p. 55). Isolated from the bodies of other Blacks, permanentlydisoriented by the frequent change in costume, Manzano's body is, quite literally, displaced. If one looks for the space allotted that body in the mistress'house, one will see it has none. Its place is always at the mistress'sside or at her feet,but never out of her sightor her control: "[M]y task was to get up at dawn before the othersawoke and sweep and clean all I could. Once I finishedmy duties, I would sit outside my lady's door so that,on awakening, she would find me immediately.I went wherevershe went, following her like a lap dog, withmylittlearms folded." (pp. 39-40). The threshold-by definitiona non-place, a divisoryline-is the space assigned to Manzano's body, the locus of his exploitation.In it,the body is no longer a body but a tool and a buffer:"[I] stayed

29 On a much larger scale, isolation was, of course, a well-known means of ensuringthe good functioning of the slave system.NewlyarrivedAfricanswere routinely mixed up ethnically so thatno slave group consistedof Africansof one ethnic origin.Communicationwas much impeded if not rendered impossible:"Plantation for owners,in fact,had a vested interest in not permitting slaves to interactfreely, withsocial cohesion mightcome a sense of solidarity." (Manuel Moreno Fraginals, Essays on "Cultural Contributionsand Deculturation,"in Africain Latin America: History, Culture and Socialization, ed. Manuel Moreno Fraginals,trans.Leonor Blum [New York: Holmes and Meier, 1984), p. 7. 30 "Boys and girlswore a one-piece shirt withone lateralseam.... Footwear was never handed out. There was even an eighteenth century Frenchdecree forbidding givingshoes to Blacks because 'shoes torturedtheirfeet'."Moreno Fraginals,"Cultural Contributions," p. 16.

410

SYLVIAMOLLOY

-anyonewho tried to enter,or fetching outside her door, stopping whom she called for,or being silentif she slept." (p. 51). To be on his mistress'sthreshold,to be that thresholdwherevershe goes, interceptingundesirable contact, is the function of Manzano's was played in the home of the Gomes body: "In the eveningsmonte ladies and, as soon as she sat down, I had to stand behind her chair with my elbows spread out, preventingthose who were standing from pushing her or grazing her ears with their arms." (p. 65) Indeed, the only place where his body escapes the controlof his mistressis the common lavatory: "Regularly the common room was my place for meditation.While I was there I could thinkof thingsin peace" (p. 68).31 The lavatoryas a refuge and a place to be, while clearlynot an originalconcept,allows me to explore anotheraspect of Manzano's one that Madden deletes completely,and bodily manifestations, one that slowlybut surely,I hope, will bring me closer to ManSeveral times zano's problematicrelationwithbooks and writing. in his text, Manzano stresses his hunger, more specifically,his givingit an importancethat surpasses the cliche of the gluttony, growingboy. "I was veryfearfuland I liked to eat," ever-hungry describeshimselfas a child. A way (p. 38) is the way he succinctly of repossessing his body, this voraciousness is also a powerful means of rebellingagainst limits: thatcame my I ate everthing hungry, always that, It is notsurprising and as I did not a great glutton, forwhich reasonI wasconsidered way, and swallowed myfood myself have a fixedtimeforeatingI stuffed that in frequent indigestions and thatresulted chewing without nearly needsand that gotmepunished tocertain attending had me frequently

... (p. 39)

As there is no place for Manzano's body, there is no specifictime carves a forhis eating. However, in the same way thathe furtively of he will, is a which in the waste, place lavatory, space for himself "When his nourishment: they make leftovers no less furtively, unleft I to was they everything up pick dined or supped quick about it forwhen theygot up to leave eaten and I had to be crafty the table I had to go withthem." (p. 40) It is by building on this and, I notion of the residual, neglected by Manzano's translators

31 A statementMadden incrediblymistranslates as "[M]y only comfortat that momentwas the solitude of my room." (Manzano, TheLifeand Poems,p. 105)

M L N

411

that I wish to approach his relation may add, his commentators,32 to books. This relation is, of course, notoriouslyone-sided. Manzano's yet forthe letter, gluttony for food is only matchedby his voracity denied him: books are unavailable,reciting thatletteris constantly forbidden.(Even when Manzano pubby heart punished, writing lishes, as he will later, he will do so by special permission.)The indeed the verynotion notion of an archive,of a culturaltotality, of a book, whichinspiredsuch awe in a Sarmiento,the "man witha alien to Manzano. His is a veryparticbook in his hand," are totally deular scene of reading, for he only has access to fragments, valued snippets from an assortmentof texts he comes across by fromhis masters'culturaltable: chance, leftovers ofreading wasreadable whatever SinceI wasa little boyI had thehabit I wasalways picking in mylanguageand whenI was out on thestreet it tillI learned paperand ifitwasverseI did notrest up bitsof printed byheart. (pp. 65-66) Even before knowing how to read, the child is a collector of texts. Under the tutelage of his firstmistress,the Marquesa de enough, was herselfa poet33-he memJustiz-who, interestingly orizes eulogies, shortplays,the sermonsof Fray Luis de Granada and bitsof operas he is taken to see. He becomes, veryearlyon, a memory machine. As the young Sarmiento a few most efficient years later, his giftis exhibited before company, yet unlike Sarmiento,thatgiftis not allowed to followitsnormalcourse. As soon as the young Manzano uses his prodigious memoryfor himselfhe is regarded withsuspicion: "When I was twelveI had alreadycomposed many stanzas in my head and thatwas the reason my godparentsdid not want me to learn how to writebut I dictatedthem from memoryto a young mulattocalled Serafina." (p. 38). Manzano is condemned to orality-not in vain is he nicknamed of the poems he composes "Golden Lips"; and, when his recitation mentallyand keeps in "the notebook of versesof mymemory"(p. he is condemned to silence: 41) is judged too disruptive, toomuchand that theold servants I chatted found outthat Mymistress in thehousegathered aroundme whenI wasin themoodand enjoyed

32 Withthe exception of Antonio Vera Le6n's perceptive mentionof Manzano in la narrativade Miguel Barnet," Diss. Princeton1987. "Testimonios,reescrituras: 33 Friol, p. 48.

412

SYLVIAMOLLOY

hearing my poems ... [She] who never lost sightof me even asleep she dreamed of me spied on me one winternighttheyhad made me repeat a storysurrounded by many children and maidservantsand she was hidden in the otheryroom behind some shutters or blinds. Next day for no good reason I received a good thrashing and I was made to stand on a stool in the middle of the room, a big gag in my mouth, with signs hangingon mychestand on myback I cannot rememberwhattheysaid and it was strictly forbiddenfor anyone to engage in conversationwith me and if I even tried to engage one of my elders in conversationhe was to give me a blow. (p. 41) Lacking books, the "notebook of [Manzano's] memory" will have to do. A repository for his models (the poems he hears, or occasionally reads, or picks up in the streets), it also stores the poems he continues to compose even if he cannot write them down or say them out loud. In the same manner, in the absence of writing, oblique means of leaving a trace on paper must be found. I quote from an admirable passage describing the drawing lesson given the mistress and her children, which Manzano, a passive attendant, turns to his profit: chairand thereI [I] too would be presentstandingbehind mymistress's stayedthroughoutthe class as theyall drew and Mr. Godfria [probably Godfrey]who was the teacher went fromone to another of those who were drawing saying such and such here correctingwith the pencil there and fixingsomethingover there,throughwhat I saw and heard as a regcorrectedand explained I found myself ready to count myself ular attendantof the drawing class I forgetwhich one of the children gave me an old brass or copper pen and a pencil stub and I waited till theythrewaway a draftand the next day afterhaving looked around me I sat in a corner my face to the wall and I startedmaking mouths eyes ears eyebrowsteeth ... and taking a discarded draftwhich was untorn ... I copied it so faithfully thatwhen I finishedmymistress was gazing at me attentively although pretendingnot to see me ... From all sortsof draftsto me in thatmomenton everybodystartedthrowing my corner,where I half lay on the floor. (p. 40) Relying heavily on residue and mimesis, Manzano's drawing lesson reverts the order of the lesson of his masters. Fished out of a waste basket or thrown to him like a bone, this used up matter, discarded from above, is given new life and value as it is used below-in the corner, on the floor, in the serf's place. From copying drafts, Manzano will go on to copying script and to writing itself. During his short, happy time in the service of the Marquesa's

M L N

413

son, Nicolas Cardenas y Manzano, he recognizes that the furtive takenup "to give of his master'smanual of rhetoric, memorization fullyapply what he cannot since learning,"is unproductive myself useful" (p. more something myself he learns. Deciding to "teach than no less striking manner in a write, 57), he teaches himselfto inventive equally to an resorting draw, himself to when he taught of refuse.Buyingpen and veryfinepaper, he rescues his recycling and, flatmaster'scrumpled notes and discarded scraps of writing tracesthem teningthem out under one of his fine sheets,literally "and with this inventionbefore a month was over I was writing lines shaped like my master'sscript...." (p. 57) His master,"who loved me not like a slave but like a son," (p. 56) opposes these effortsand (in this respect, no differentfrom his mother) "ordered me to leave that pastime,inappropriateto my situationin life,and go back to sewing."(p. 57) That thissame masterwas "an and, inon thisisland,"34 protectorof public instruction illustrious deed, would later be presidentof the Education Section of the Sodel Pass, does not lack ironybut should de Amigos ciedadEcon6mica not surprise us.35 Whereas Manzano sees writingas useful,his master(who sends him back to his sewing,a task,Manzano claims, and time,withinthe he was not neglecting)considers it a pastime in work.36 cannot be passed,it mustbe measured slave system,

L6pez Prieto,Parnaso cubanop. 252. For the way in which Blacks were denied education, see Ram6n Guirao, Bohemia, Aug. 26, 1934, pp. 43-44, "Poetas negros y mestizosen la epoca esclavista," 123-124. 36 "When, for reasons beyond theircontrol,the slave-owners had no productive work for the slaves to do, they devised unproductivework for the slaves such as themto theirplace of movingobjectsfromone place to anotherand thenreturning a origin. A slave withoutworkwas an elementof dissolutionfor the whole system, factorof possible rebellion."(Moreno Fraginals,"Africain Cuba. . . ," p. 200). Examples of this inventedwork to avoid emptytime (or pastimes) may be found in whetherit was Manzano: "It was my task every half hour to clean the furniture, dusty or not." (p. 48); and: "I was sent to polish the mahogany so that I would spend my timeweeping or sleeping." (p. 56). A study of time, of the different notationsof time in Manzano's Autobiografza would be of definiteinterest.Criticshave pointed to the apparent contradiction between Manzano's exceptional memoryfor literatureand his poor memoryconimprecisionaltercerningfacts.Chronologyand time notationsare indeed blurry, nating with very precise deictics ("a littlebefore eleven," etc.). I suggest the following remarkson perception of time by slaves, again by Moreno Fraginals,as a on Manzano's sense of time: possible solutionto the controversy

34 35

The unnatural "Aftersome time this accumulated fatigue became irrteversible. rhythm musthave broughtabout a deep-seated dissociationbetweenhuman time between and the time required for production,a total lack of synchronization biologicalcapabilitiesand the taskthathad to be performed."(Moreno Fraginals, and Deculturation,"p: 18) "Cultural Contributions

414

SYLVIA MOLLOY

Identity and identificationare words that occur nowhere in Manzano's autobiographyexcept here, in the course of the writing lesson I have described. Manzano tells how, in preparing his master'stable, chair, and books everymorning,he "began identithe learning withhis habits;" (p. 56) and, when summarizing fying process observed above, he explains that "that is why there is a and mine." (p. 57) What between his handwriting certainidentity with of course, is that Manzano does not identify is noteworthy, withhis reading,withhis writing, the masterhimself:he identifies achieve withthe meansthroughwhichhe, Manzano, willultimately For there are two storiesin Manzano's autobioghis own identity. of the withDel Monte's request,is the story raphy: one, complying if not more so, is the story just as important selfas slave; the other, of thatslave self as reader and writer. Manzano would His master's initial objection notwithstanding, withconsiderablesuccess. From a modestcotcontinuehis writing somehow run out of the Marquesa's home ("I wrote tage industry many notebooksof stanzas in forcedmeter,which I sold" [p. 66]), he would go on to publish with special permission(Poesiasliricas, 1821; Florespasageras [sic], 1830), on to Del Monte's patronage, (Zafira and on to moderate renown as a poet and as a playwright 1842). What strikesthe modern reader about Manzano's poetry, however,is its desperatelyconventional,measured and ultimately which,if correct style.It is mediocre Neoclassicismat itsveryworst, declares that one thinksof it,was to be expected. Manzano himself Spanish poet who transhis model was Arriaza, the contemporary lated Boileau; Del Monte, an ardent Neoclassicist,helped Manafterall, was verymuch zano edit his poetry;and Neoclacissicism, the fashion of the day. Besides being the style Manzano read, heard and memorized,it was, I suspect,a stylethataffordedhim its handy comfortpreciselybecause of its readymade formalism, cliches, its lofty abstraction, its reassuring meters. Manzano's avowed liking for pie forzado- the prefixed "mold" of the poem itself-confirms,I bethe writing (verse and rhyme)determining lieve, thissuspicion. It is pointlessto search these poems forpoetic personal confessions or reflectionson slavery; ludioriginality, ovis "the cryof thepatiens crous to findin them,as does one critic, reflecting injuriae,"37 or, as does another, a "creative suffering"

p. 50. Calcagno, Poetasde color,

37

M L N

415

"the blues or spiritualatmosphere [sic]."38Yet it is equally short(A fact of sighted to dismiss them because they are imitations.39 called them"cold imitawhichManzano was well aware: he himself tions" in his autobiography[p. 66]). Manzano's poetry,I argue, is it is so imitative, because it is such a deliboriginalpreciselybecause that erate and totalact of appropriationof the reading and writing had been denied him. In his poetry,Manzano models his self and his "I" on the voice and the conventionsof his masters.His second wife,the nineteenas a gold nugget year-oldfree mulattoMaria del Rosario, "pretty abstractDelia. (A from head to toe"40becomes a conventionally previous muse, sung in the 1821 poems, perhaps his firstwife Marcelina Campos, receivesthe Catullianname of Lesbia.)Another poem, "A Dream," addressed to Manzano's brotherFlorencio,describes the latter as a "robust Ethiopian"-an ordinary,pretentious euphemism for Blacks which would be used on Manzano himself("a poet of the Ethiopian race"41).Manzano's poems relish artificiality: streamsbecome lymphs,winds are zephyrs,heaven is the empyrean.Hyperbatonand prosopopeia abound, mannerisms and classicalreferencesare frequent;so are resounding,meaningless fillers-"en divinal trasunto,"to give but one example.42"His ear taughthim the cadence of verse; his genius dictatedto him the marksof good taste,"writesCalcagno, intenton forcingManzano into the stereotype of the uneducated, "natural"poet.43But those conventions marks of "good taste" (another name for the literary of the day) were less attributable to "genius" than to Manzano's a giftso excessive it contained in extraordinary giftof mimicry, by itself itsown undoing.44Manzano's poetryis so overdetermined

38 Antonio Olliz Boyd, "The Concept of Black Awareness as a Thematic ApMiriam Deproach in Latin American Literature,"in Blacksin HispanicLiterature, Costa, ed. (Port Washington,N.Y.-London: KennikatPress, 1977), p. 69. in Blacksin 39 MyriamDeCosta, "Social Lyricism and the Caribbean Poet/Rebel," pp. 115-6. For a somewhatmore balancedjudgment on the pheHispanicLiterature, nomenon of imitation,see Samuel Feij6o, "AfricanInfluence in Latin America: p. 148. in America, Oral and WrittenLanguage," in Africa p. 40 Letterof 11 December 1834 to Domingo Del Monte, Manzano, Autobiograffa, 82. 41 L6pez Prieto,p. 251. de la serenisimaInfantadofia Maria Isabel 42 "Poesia (En el felizalumbramiento Luisa de Borb6n)," cited in Friol, p. 99. 43 Poetasde color, p. 51. 44 "In Manzano, withhis exaggerated rhetoric, his excessivedecorum,his exalted of breaking out of a literarycode we see how the impossibility sentimentalism,

416

SYLVIAMOLLOY

such a comprehensivereservoirof cliches, it constitutes imitation, to the turnsinto parody. His only contribution that it unwittingly theatre,Zafira,a play in verse, fared no better.It is a "Moorish" romance in the spiritof the period, as closelydependent on conspeaking, as were the poems in theirchoice vention,thematically of form. howAfterthe poems and the play, a look at the Autobiografza, cannot but disconcertthe reader. If the poetry ever perfunctory, the storyof Manzano's gave the impressionof being overwritten, as a poet produces quite the opposite lifeand of his self-discovery exists that Manzano was helped more with effect.The possibility than withthe second: his poems were reviewedand edited the first by del Monte before publication whereas the manuscriptof the at least the one thatwas published in 1937, apparautobiography, entlydid not benefitfromeditorialhelp. (Del Monte had charged Suarez y Romero with editing Manzano's text and Suarez apparentlycomplied;45yet that corrected version, the whereaboutsof which are unclear, was not the one that was finallypublished.) showsis an What a comparisonof both,poetryand autobiography, Manzano's production as much as unquestionable split,affecting his self-imageas a writer. rhecomfortable The lyric"I" of Manzano's poetryis a relatively one into which Manzano seems to fitwithouteftoricalconstruct, fort.His models, stored eitherin his memoryor in his straybitsof print,are easy to call up and reassuringin their authority:they are, afterall, the models of the master.However, when Manzano down in when he writeshimself writesprose, and more specifically his autobiographyas a black man and a slave,thereis no model for image- to be rescued from him, no founding fiction-no master texts. In order to validate his autobiographicalgesture and thus authorize himself, Manzano cannot pick and choose from his scraps because those scraps do not contain the makings of his as an absence. If those image, or rathercontain them,unwritten, Manzano to speak allowing mimicry, scraps may be used forpoetic with his master'svoice, theydo not lend themselveseasily to the

forcesthe black writerto masterit throughexhaustionand excess." (Roberto Gonin the zailez Echevarria, "Nota critica sobre Pedro Barreda, The Black Protagonist [Madrid: Porrua Turanzas, 1983], p. 245). Cuban Novel,"in Isla a su vuelofugitiva

45

See the Sudrez y Romero letterdescribinghis editingtask in Friol, p. 231.

M L N

417

expression of an autobiographical persona they in no way prefigure.One can trace lettersfromthe master'srefuse; one cannot, model. however,trace a self forwhichthereis no written as Manzano wroteit,withits run-insentences, The Autobiografia breathless paragraphs, dislocated syntax and idiosyncraticmisspellings,vividlyportraysthat quandary-an anxietyof origins, ever renewed, that provides the text with the stubborn,uncontrolledenergythatis possiblyits major achievement.The writing, we have of Manzano, his greatest in itself, is the best self-portrait to literature;at the same time,it is what translators, contribution to clean up this cannot tolerate."It would suffice editorsand critics forthe clear and touchingmanner in text,freeingit of impurities, in all itssimto reveal itself whichManzano relateshis misfortunes plicity," writes Max Henriquez Urefia.46This notion (shared by many) that there is a clear narrative imprisoned, as it were, in waitingfor the hand of the cultivatededManzano's Autobiografia, itorto freeit fromthe slag-this notionthatthe impure textmust be replaced by a clean (white?) version for it to be readable thatof denyingthe text amounts to another,aggressivemutilation, readability in its own terms.Of all the "perpetual scars" thatmark Manzano's body, thiscould well be the cruellest.

Yale University

46 Max Henriquez Urefia,Panoramahist6rico de la literatura cubana (Puerto Rico: Ediciones Mirador, 1963), p. 184.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- 4) VERANI, HUGO - La Heterogeneidad de La Narrativa Vanguardista Hispanoamericana PDFDokumen12 halaman4) VERANI, HUGO - La Heterogeneidad de La Narrativa Vanguardista Hispanoamericana PDFMorgana DamicBelum ada peringkat

- Manuel Maples Arce Salvador Novo and The Origin of Mexican Vanguard AutobiographiesDokumen19 halamanManuel Maples Arce Salvador Novo and The Origin of Mexican Vanguard AutobiographiesLaura R QcBelum ada peringkat

- Kramer - Writing From The Riverbank Saer - 110Dokumen218 halamanKramer - Writing From The Riverbank Saer - 110Rafael Arce100% (1)

- Levinson, Ends of LiteratureDokumen14 halamanLevinson, Ends of LiteratureSam SteinbergBelum ada peringkat

- Folktales and Fabulation in Lucrecia Martel's FilmsDokumen18 halamanFolktales and Fabulation in Lucrecia Martel's FilmsMaría BelénBelum ada peringkat

- WaslalaDokumen12 halamanWaslalaJaxsonBelum ada peringkat

- Poetics of Ritual and Witness Cables of GenocideDokumen50 halamanPoetics of Ritual and Witness Cables of GenocideAmericanSapphoBelum ada peringkat

- Stocco, Melisa - Approaching Self-Translation in Latin American Indigenous Literatures. The Mapuche Bilingual Poetry of Elicura ChihuDokumen16 halamanStocco, Melisa - Approaching Self-Translation in Latin American Indigenous Literatures. The Mapuche Bilingual Poetry of Elicura ChihulaszlosanglotBelum ada peringkat

- Escritura MaterialDokumen96 halamanEscritura MaterialClaudia Poblete100% (1)

- The Ode As An Oratorical Genre PDFDokumen33 halamanThe Ode As An Oratorical Genre PDFAna NikolicBelum ada peringkat

- Healy Lacanha ValleyDokumen5 halamanHealy Lacanha ValleyIvonne Sanchez VazquezBelum ada peringkat

- Exico's Uins: Raúl Rodríguez-HernándezDokumen230 halamanExico's Uins: Raúl Rodríguez-HernándezbernardonunezmagdaleBelum ada peringkat

- MR and Mrs ElliotDokumen1 halamanMR and Mrs Elliotmgupta72Belum ada peringkat

- Rabasa Writing Violence On The Northern FrontierDokumen380 halamanRabasa Writing Violence On The Northern FrontierRosa LuxemburgoBelum ada peringkat

- Voces Asperas. Narrativas Argentinas de Los 90Dokumen207 halamanVoces Asperas. Narrativas Argentinas de Los 90MarceloVidal100% (2)

- Formación Del Pensamiento Crítico-Literario en Hispanoamérica. Epoca ColonialDokumen12 halamanFormación Del Pensamiento Crítico-Literario en Hispanoamérica. Epoca ColonialKevin Sedeño-GuillénBelum ada peringkat

- Pettas A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Bookstore The Inventory of Juan de JuntaDokumen250 halamanPettas A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Bookstore The Inventory of Juan de JuntaRené Lommez GomesBelum ada peringkat

- Laura Maccioni, Líneas de Fuga, Literatura y Política en Reinaldo Arenas y Juan José Saer, 1960-1975, Tesis Dirigida Por Juan Carlos Quintero-HerenciaDokumen260 halamanLaura Maccioni, Líneas de Fuga, Literatura y Política en Reinaldo Arenas y Juan José Saer, 1960-1975, Tesis Dirigida Por Juan Carlos Quintero-HerenciacarlostomatissBelum ada peringkat

- Eagleton-Flight To The RealDokumen7 halamanEagleton-Flight To The RealAdela Pineda FrancoBelum ada peringkat

- The Revolution of 1910 and Its Aftermath: La Muerte de Artemio CruzDokumen14 halamanThe Revolution of 1910 and Its Aftermath: La Muerte de Artemio CruzfeskerBelum ada peringkat

- Nancy Morejon PDFDokumen11 halamanNancy Morejon PDFninopalinoBelum ada peringkat

- Mexican Literature in The Neoliberal EraDokumen14 halamanMexican Literature in The Neoliberal EraEliana Hernández100% (1)

- Rose Corral - Ficciones Limítrofes: Seis Estudios Sobre Narrativa Hispanoamericana de VanguardiaDokumen13 halamanRose Corral - Ficciones Limítrofes: Seis Estudios Sobre Narrativa Hispanoamericana de VanguardiaAndrea Abarca OrozcoBelum ada peringkat

- AVELAR, Idelber. Heavy Metal Music in Postdictatorial Brazil Sepultura and The Coding of Nationality in Sound PDFDokumen19 halamanAVELAR, Idelber. Heavy Metal Music in Postdictatorial Brazil Sepultura and The Coding of Nationality in Sound PDFNatália RibeiroBelum ada peringkat

- Doris Sommer - Foundational Fictions / Chapter 1, Part 1 and 2Dokumen27 halamanDoris Sommer - Foundational Fictions / Chapter 1, Part 1 and 2Thelma Jiménez Anglada100% (7)

- María Rosa Menocal - Shards of Love - Exile and The Origins of The Lyric (1993, Duke University Press) - Libgen - LiDokumen193 halamanMaría Rosa Menocal - Shards of Love - Exile and The Origins of The Lyric (1993, Duke University Press) - Libgen - Libagyula boglárkaBelum ada peringkat

- Romanticism 2012-13 CatalogueDokumen28 halamanRomanticism 2012-13 CataloguePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Chaytor, The Medieval ReaderDokumen8 halamanChaytor, The Medieval ReaderHeloise ArgenteuilBelum ada peringkat

- CamScanner Scans - Multiple PagesDokumen13 halamanCamScanner Scans - Multiple PagesVictoria BlueBelum ada peringkat

- Constellations of The Audiomachine CTM 2017 Exhibit BookletDokumen17 halamanConstellations of The Audiomachine CTM 2017 Exhibit BookletVoltaje PrietoBelum ada peringkat

- The Past in the Present: Memory Discourses in CultureDokumen93 halamanThe Past in the Present: Memory Discourses in CultureChetananandaBelum ada peringkat

- Eugene Onegin - Pushkin's Novel in VerseDokumen206 halamanEugene Onegin - Pushkin's Novel in VerseSebastián SantamaríaBelum ada peringkat

- El Papel de La Mujer en La Historia Maya Quiche PDFDokumen20 halamanEl Papel de La Mujer en La Historia Maya Quiche PDFAnabelLedesmaBelum ada peringkat

- Anotaciones de Otoño, Julio MirandaDokumen45 halamanAnotaciones de Otoño, Julio MirandaAlejandro UsecheBelum ada peringkat

- Panchito ChapopoteDokumen46 halamanPanchito ChapopoteRodolfo MataBelum ada peringkat

- Sobre La Emoción en El Poema Alicia GenoveseDokumen21 halamanSobre La Emoción en El Poema Alicia GenovesejlanfrancosacgobernaBelum ada peringkat

- Trauma and Poetics of Affect - Nanci BuizaDokumen22 halamanTrauma and Poetics of Affect - Nanci BuizaCésar Andrés ParedesBelum ada peringkat

- Realist Floor PlanDokumen11 halamanRealist Floor PlandivaBelum ada peringkat

- El Antimodernismo. Sátira e Ideología de Un Debate TransatlánticoDokumen13 halamanEl Antimodernismo. Sátira e Ideología de Un Debate Transatlánticogrão-de-bicoBelum ada peringkat

- Jorge Marcone - de Retorno A Lo Natural: La Serpiente de Oro, La "Novela de La Selva" y La Crítica EcológicaDokumen11 halamanJorge Marcone - de Retorno A Lo Natural: La Serpiente de Oro, La "Novela de La Selva" y La Crítica EcológicaluyalanBelum ada peringkat

- Writing and Bare Life: Locura and Colonialism in Matos Paoli's Canto de La LocuraDokumen14 halamanWriting and Bare Life: Locura and Colonialism in Matos Paoli's Canto de La LocuraVirtual BoricuaBelum ada peringkat

- Personal Testimony Fernand BraudelDokumen21 halamanPersonal Testimony Fernand BraudelHenrique Gerken BrasilBelum ada peringkat

- World Lite: What Is Global LiteratureDokumen15 halamanWorld Lite: What Is Global LiteratureGiselle MartínezBelum ada peringkat

- Edipo Entre Los Inkas - César Calvo PDFDokumen15 halamanEdipo Entre Los Inkas - César Calvo PDFRenzo Medina VicuñaBelum ada peringkat

- Pratt. Las Mujeres y El Imaginario Nacional en El Siglo XIX América LatinaDokumen13 halamanPratt. Las Mujeres y El Imaginario Nacional en El Siglo XIX América LatinaMariteDouzetBelum ada peringkat

- Mass Immigration Drove Modernization in ArgentinaDokumen18 halamanMass Immigration Drove Modernization in ArgentinajoaquingracBelum ada peringkat

- Heim y Tymowski - 2006 - Guidelines For The Translation of Social Science Texts PDFDokumen30 halamanHeim y Tymowski - 2006 - Guidelines For The Translation of Social Science Texts PDFJosé SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- Worksheets Myriam Fuentes Mendoza PDFDokumen51 halamanWorksheets Myriam Fuentes Mendoza PDFMyriam Fuentes Mendoza100% (1)

- Benjamin, W. The Crisis of The NovelDokumen7 halamanBenjamin, W. The Crisis of The NovelPaula LombardiBelum ada peringkat

- El Cristo de La Rue Jacob Severo SarduyDokumen14 halamanEl Cristo de La Rue Jacob Severo SarduyFranke Alves de AtaydeBelum ada peringkat

- Carlos Soto Roman 11 Reading GuideDokumen4 halamanCarlos Soto Roman 11 Reading GuideEduardo BelloBelum ada peringkat

- Disch, Thomas M - DescendingDokumen10 halamanDisch, Thomas M - DescendingKiranBelum ada peringkat

- Fernand Hallyn, The Poetic Structure of The WorldDokumen143 halamanFernand Hallyn, The Poetic Structure of The WorldAnonymous cbBpObBelum ada peringkat

- LA HORA ENCANTADA: Sonetos de Amor Lunático/TITLEDokumen83 halamanLA HORA ENCANTADA: Sonetos de Amor Lunático/TITLEAdam DunnBelum ada peringkat

- La Literatura y El Arte Modernistas El Erotismo Mortificante en M XicoDokumen12 halamanLa Literatura y El Arte Modernistas El Erotismo Mortificante en M XicoLaloArnaudBelum ada peringkat

- CubaguaDokumen44 halamanCubaguaJuan Antonio HernandezBelum ada peringkat

- Levi Bryant - Politics and Speculative RealismDokumen7 halamanLevi Bryant - Politics and Speculative RealismSoso ChauchidzeBelum ada peringkat

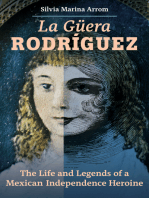

- La Guera Rodriguez: The Life and Legends of a Mexican Independence HeroineDari EverandLa Guera Rodriguez: The Life and Legends of a Mexican Independence HeroineBelum ada peringkat

- The Life And Death Of Jason: "Have nothing in your house that your house that you do not know to be useful, or to be beautiful."Dari EverandThe Life And Death Of Jason: "Have nothing in your house that your house that you do not know to be useful, or to be beautiful."Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Bulletin of The History of MedicineDokumen6 halamanThe Johns Hopkins University Press Bulletin of The History of MedicineLaura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat

- Etymology SpitzerDokumen3 halamanEtymology SpitzerLaura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat

- Sommers (Notes)Dokumen8 halamanSommers (Notes)Laura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat

- Ficciones Paranoicas 08Dokumen7 halamanFicciones Paranoicas 08Laura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat

- Spitzer Etymology of PetDokumen7 halamanSpitzer Etymology of PetLaura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat

- Madame Bovary in English Part 1Dokumen35 halamanMadame Bovary in English Part 1Laura GandolfiBelum ada peringkat