0502 - Plyometrics For Kids - Facts and Fallacies

Diunggah oleh

mednasrallah0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

256 tayangan27 halamanbn,

Judul Asli

0502_Plyometrics for Kids_Facts and Fallacies

Hak Cipta

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen Inibn,

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

256 tayangan27 halaman0502 - Plyometrics For Kids - Facts and Fallacies

Diunggah oleh

mednasrallahbn,

Hak Cipta:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 27

National Strength and Conditioning Association

Bridging the gap between science and application

April 2006

Volume 5, Number 2

www.nsca-lift.org/perform

Conditioning

Fundamentals

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

2

C

ontents

Conditioning Fundamentals

Plyometrics for Kids:

Facts and Fallacies

Avery D. Faigenbaum, EdD, CSCS

Plyometric training for kids is a topic that is lled with con-

troversy and misinformation. Tis article discusses some of

the common myths associated with plyometric training and

youth.

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively:

Te Missing Link

John M. Cissik, MS, CSCS,*D,

NSCA-CPT,*D

Te ability to take the rst few steps explosively is very impor-

tant in athletics. Tis article looks at why the rst few steps

are important, the proper technique for the rst few steps, and

drills to both learn and improve the starting technique. Sample

programs are also included.

13

Ounce of Prevention

Lower Extremity Stretching Program

for Endurance Runners

Jason Brumitt, MSPT, SCS, ATC, CSCS,*D

Inexibility or muscle tightness may contribute to muscular

related running injuries. Tis article features a lower extremity

stretching program for the endurance running athlete.

Training Table

Sensible Supplements

Debra Wein, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-CPT

Supplements usage by athletes continues to grow. Tis article

discusses the regulation, marketing, and labeling of supple-

ments.

MindGames

Set Yourself Up For Success

In Practice

Suzie Tuffey Riewald, PhD, NSCA-CPT,*D

If you are looking for success in competition, you need success

in practice. Tis article discusses how to set up practice goals,

analyze past practices, and things you can do in each practice

session to help promote success.

9

17

26

Departments

FitnessFrontlines

G. Gregory Haff, PhD, CSCS

Learn the latest news from the eld on the eects of stretch-

ing, sled pulling, and whole body vibration on sprint perfor-

mance.

In The Gym

Exercise and Heat Stroke

Joseph M. Warpeha, MA, CSCS,*D,

NSCA-CPT,*D

With the approach of summer, more individuals begin exer-

cising outside. However as temperatures begin to rise, heat

related illnesses become a major concern. Tis article discusses

heat related illnesses and provides guidelines for exercise in hot

environments.

4

19

6

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform

NSCAs Performance Training Journal is a publication

of the National Strength and Conditioning Association

(NSCA). Articles can be accessed online at

http://www.nsca-lift.org/perform.

All material in this publication is copyrighted by

NSCA. Permission is granted for free redistribution of

each issue or article in its entirety. Reprinted articles

or articles redistributed online should be accompanied

by the following credit line: Tis article originally

appeared in NSCAs Performance Training Journal, a

publication of the National Strength and Conditioning

Association. For a free subscription to the journal,

browse to www.nsca-lift.org/perform. Permission to

reprint or redistribute altered or excerpted material will

be granted on a case by case basis; all requests must be

made in writing to the editorial o ce.

NSCA Mission

As the worldwide authority on strength and condition-

ing, we support and disseminate research-based knowl-

edge and its practical application, to improve athletic

performance and tness.

Talk to us

Share your questions and comments. We want to hear

from you. Write to Performance Training Editor,

NSCA, 1885 Bob Johnson Drive, Colorado Springs,

CO 80906, or send email to kcinea@nsca-lift.org.

Editorial Of ce

1885 Bob Johnson Drive

Colorado Springs, Colorado 80906

Phone: +1 719-632-6722

Editor: Keith Cinea, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

email: kcinea@nsca-lift.org

Sponsorship Information: Robert Jursnick

email: rjursnick@nsca-lift.org

Editorial Review Panel

Kyle Brown, CSCS

Scott Cheatham DPT, ATC, CSCS, NSCA-CPT

John M. Cissik, MS, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

Shane Domer, MEd, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

Chris A. Fertal, CSCS, ATC

Michael Hartman, MS, CSCS,*D

Mark S. Kovacs, MEd, CSCS

David Pollitt, CSCS

David Sandler, MS, CSCS

Brian K. Schilling, PhD, CSCS

Mark Stephenson, ATC, CSCS,*D

David J. Szymanski, PhD, CSCS,*D

Chad D. Touchberry, MS, CSCS

Randall Walton, CSCS

Joseph M. Warpeha, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

3

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

4

running velocity only during the 0 10

m portion of the sprint. As a result of

this increase, the acceleration phase (0

20 m) also exhibited a greater overall

sprint velocity. However, resisted sled

pulling resulted in no change in running

velocity during the 20 50 m assess-

ment. Conversely, the US group exhib-

ited no signicant improvements in

the acceleration phase, and signicantly

greater improvements in the maximum

velocity phase (20 50 m) of the tested

sprint. Te authors speculate that the

improvements in the acceleration phase

in the RS group were probably caused

by increases in muscular strength. Since

neither group performed any resistance

training, it is likely that the improve-

ments noted by the RS group are a result

of increases in muscular strength. Based

upon these results it was concluded that

weighted sled pulling may oer some

benets when improvements in accelera-

tion are needed, while maximal speed is

improved by unloaded sprint training.

However, it is unknown at this time if

this benet will still exist if the athlete

is participating in a periodized strength

training program designed to improve

leg an hip strength and power produc-

ing capacity.

Zafeiridis A, Saraslanidis P, Manou V,

Ioakimidis P, Dipla K, Kellis S. (2005).

Te eect of resisted sled-pulling sprint

training on acceleration and maximum

speed performance. Journal of Sports

Medicine and Physical Fitness, 45(3):284

290.

FitnessFrontlines

G. Gregory Haff, PhD, CSCS

Should You Stretch Before

You Sprint?

Recently researchers from the

Department of Kinesiology at Louisiana

State University examined the eects of

a variety of stretching protocols on 20

m sprint times. Eleven males and ve

females were recruited from the nation-

ally ranked Louisiana State University

track and eld team to participate in

the investigation. Subjects participated

in the dierent stretching protocols in

a randomized manner. Prior to each

of the stretching protocols all athletes

performed a series of warm-up exercises

which included 1) an 800 m jog, 2)

forward skips 4 x 30 m, 3) side shu es

4 x 30 m, and 4) backwards skips 4 x

30 m. Four stretching protocols were

then tested: 1) no stretching on either

leg (NS), 2) both legs stretched (BS),

3) forward leg in the starting position

stretched (FS), 4) rear leg in the starting

position stretched (RS). Each stretching

protocol was performed four times with

each stretch being held for 30 s. Overall

the data suggested that the NS condi-

tion produced the fastest 20-m sprint

time (3.17 0.04 s), while BS (3.21

0.04 s), FS (3.21 0.04 s), and RS (3.22

0.04 s) produced the slowest sprint

times. Tere were no statistical dier-

ences noted between the BS, FS, and

RS groupings. Based upon the ndings

of this investigation the authors sug-

gest that performing passive stretching

exercises before sprinting activities can

result in a signicant decline in sprinting

speed. Terefore, it was recommended

that the use of passive stretching tech-

niques be avoid by athletes prior to the

performance of sprinting activities.

Nelson AG, Driscoll NM, Landin DK,

Young MA, and Scheznayder IC. (2005).

Acute eects of passive muscle stretching

on sprint performance. Journal of Sports

Sciences, 23(5):449 454.

Does Resisted

SledPulling Improve

Sprint Performance?

Sprint training which employs load pull-

ing has been widely applied to enhance

sprint performance of many athletes.

Event though the practice of loaded

sled-pulling is very popular, very little

scientic data has been collected to sup-

port this practice. Researchers from the

Department of Physical Education and

Sport Science, at Aristotelio University

of Tessaloniki in Tessaloniki, Greece

recently performed an investigation in

order to examine the eects of resisted

and un-resisted sprint training on sprint

performance. Twenty-two recreationally

trained athletes were randomly divided

into a resisted (RS) and un-resisted (US)

sprint training program. Each group

participated in an 8week sprint training

regime. Te RS group was required to

pull a 5 kg sled while the US group per-

formed the same sprint training regime

with out a resistance sled. Te sprint

training consisted of 4 x 20 and 4 x 50

m maximal runs that were performed

three times per week for the duration

of the investigation. Tree days prior to

and three days after the sprint training

program, each subject was tested by per-

forming two 50 m sprints. Performance

times were measured every 10 meters,

while kinematic characteristics were

evaluated during the acceleration (0

20 m) and at maximum speeds (20

50 m). Results of the study suggest that

pulling a 5 kg sled signicantly improves

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

5

Whole Body Vibration

Training Ofers No Beneft

to Sprint Trained Athletes

Te use of whole body vibration as a

training modality is gaining popular-

ity in a variety of settings. Little data

exists exploring the eects of integrat-

ing whole body vibration training into

the training practices of sprint trained

athletes. Recently, researchers from the

Department of Kinesiology at Katholieke

University Leuven, in Leuven, Belgium

investigated the eects of the addition

of whole body vibration training to the

training practices of sprinters on speed-

strength performance. Twenty highly

trained sprint athletes were recruited for

the present investigation and divided

into two equal groups. Te ve week

sprint training program for these ath-

letes consisted of

1. Interval and speed training

(2 3 sessions weekly)

2. Speed training drills (2 sessions

weekly)

3. Plyometrics (1 session weekly), and

resistance training

(3 sessions weekly)

Tis training regime was designed in a

periodized fashion in accordance with

guidelines set forth by the National

Strength and Conditioning Association.

Te vibration training group also per-

formed a series of 6 exercises designed to

work the lower body for a total vibration

exposure of 9, 13.5, and 18 minutes.

Te vibration frequency ranged between

35 40 Hz. Results of this investigation

revealed that their was no dierence

between the vibration group and the

non-vibration group after the 5 week

training regime for 1) isometric knee

exor strength, 2) dynamic knee exor

strength, 3) start time, 4) horizontal

start acceleration, 5) counter movement

vertical jump performance, and 6) 30

m sprint performance. Based upon this

investigation it appears that the utiliza-

tion of whole body vibration oers no

additional benets to the sprint athlete

who is undergoing a periodized training

regime which incorporates resistance,

plyometric, speed training, and sprint

interval training.

Delecluse C, Roelants M, Diels R,

Koninckx E, Verschueren S. (2005).

Eects of whole body vibration on mus-

cle strength and sprint performance

in sprint-trained athletes. International

Journal of Sports Medicine, 26:662

668.

About the Author

G. Gregory Ha, PhD, CSCS, is an assis-

tant professor in the Division of Exercise

Physiology at the Medical School at West

Virginia University in Morgantown,

WV. He is a member of the National

Strength and Conditioning Associations

Research Committee and the USA

Weightlifting Sports Medicine Committee.

Dr. Ha received the National Strength

and Conditioning Associations Young

Investigator Award in 2001.

FitnessFrontlines

G. Gregory Haff, PhD, CSCS

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

6

S

ummer is right around the cor-

ner which makes this a good

time to talk about the prob-

lems that can be brought on by exercise

or physical exertion in hot environ-

ments. Te human body is remarkable

in its ability to adapt to environmental

extremes as highlighted by indigenous

peoples living in climates that range

from Alaska and Siberia to the tropics

of Central America and the deserts of

Africa. Te body does have its limits

however, particularly for those who have

not been born and raised in an extreme

environment or, at the very least, have

not acclimatized (adapted).

Heat stroke (HS) is a medical emergency

and is the most severe of all heat illness

nervous system dysfunction (e.g. confu-

sion, unconsciousness), 2) hot dry skin,

and 3) core temperature >41

o

C (1

o

C

depending on the source) (3). Core tem-

perature should be measured rectally for

the most accurate assessment (2). Te

only dierence in criteria for exertional

HS is that the core temperature may

be slightly lower and profuse sweating

is often present (although skin may

be wet or dry at the time of collapse).

Other symptoms of HS include rapid

heartbeat, rapid and shallow breathing,

altered blood pressure (elevated or low-

ered), altered mental status, vomiting,

diarrhea, seizures, and coma. Classical

HS often occurs during extreme heat

waves with the elderly and very young

being particularly vulnerable. Exertional

HS typically occurs in previously healthy

young people who perform heavy or

intense exercise in hot and/or humid

environments. Te classic example is a

football player participating in two-a-

day practices in a helmet and full pads

during a Midwest summer heat wave.

A temperate climate like the Midwest

is a good example because there can be

extreme heat waves with drastic swings

es. HS is a failure of the hypothalamic

temperature regulatory center due to a

rising core temperature. In other words,

the thermostat that keeps our body

temperature in a fairly narrow operating

range breaks down and results in an

uncontrolled rise in core temperature

that can quickly become fatal if appro-

priate measures are not taken. Death can

be due to a multitude of complications

arising from the HS cascade including

heart failure or cerebral edema (3). Te

mortality associated with HS has been

quoted between 10 50% (4).

HS is classied as either classical or

exertional with only minor dierences

between the two. Te diagnostic criteria

for classical heat stroke are: 1) central

IntheGym

Exercise

and Heat Stroke

Joseph M. Warpeha, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

Table 1. Risk Factors for Heat Stroke

Major Risk Factors for Heat Stroke

Environment

- High temperature

- High humidity

- High solar radiation

- Little or no wind

Physical Activity

- Vigorous exercise

- Heavy exertion

- Intense activities

Age

- Older than 75

- Younger than 5

Other Risk Factors For Heat Stroke

Male gender Lack of acclimatization Lack of ftness

Previous heat stroke Wearing excessive clothing Obesity

Dehydration Fatigue Illness/Disease

Malnutrition Alcohol use Certain Medications

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

7

in temperature and many people are

not acclimatized to the heat like those

who live in hot climates and are more

adapted to the heat and humidity. Te

combination of an intense physical sport

like football and heavy equipment that

deters heat dissipation is particularly

dangerous in hot environments. All ath-

letes (not just football players) who

spend time training/competing in a hot

environment must take precautions to

prevent heat illnesses.

HS is the most frequent environmen-

tally-related cause of death in the U.S.

with about 400 deaths per year attrib-

uted to it (6). Surprisingly, HS is second

only to head injuries in exercise-related

deaths (3) and is the third leading cause

of death among athletes in the U.S.

(6), so the consequences of this heat

illness should not be underestimated.

HS aects virtually all of the bodys vital

systems including cardiovascular, neuro-

logical, renal, gastrointestinal, immuno-

logical, and musculoskeletal (4).

Te major risk factors for HS include a

hot environment, vigorous exercise/exer-

tion, and age. Risk factors for HS are

listed in Table 1.

Since a hot environment is the major

ingredient, it is important to take into

account all of the factors that contribute

to this heat (high environmental tem-

perature and solar radiation) as well as

those that make it more di cult for the

body to dissipate heat (high humidity

and little or no wind). Te wet-bulb

globe temperature (WGBT) is a single

index that accounts for these factors

(except wind) in an attempt to quantify

heat stress and prevent heat illness (5).

quate hydration levels and salt/electro-

lyte stores during prolonged exertion is

paramount. For the athlete or exerciser,

acclimatizing oneself to hot conditions

over several days or weeks is the most

eective way to gradually introduce the

body to a hot environment. Tis causes

adaptive mechanisms to take place and

allows the thermoregulatory system to

function more e ciently in hot envi-

ronments. If you must train in the heat,

acclimatizing yourself and following the

above precautions is the best prevention

of serious heat illness including heat

stroke.

References

1. American College of Sports Medicine.

(2006). ACSMs guidelines for exercise

testing and prescription, 7th edition.

Baltimore: Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins.

2. strand PO, Rodahl K, Dahl HA,

Strmme SB. (2003). Textbook of work

physiology: physiological bases of exer-

cise, 4th edition. Champaign: Human

Kinetics.

3. Brooks GA, Fahey TD, Baldwin KM.

(2005) Exercise physiology: human bioen-

ergetics and its applications, 4th edition.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

4. Grogan H, Hopkins PM. (2002)

.Heat stroke: implications for critical

care and anaesthesia. British Journal of

Anaesthesia, 88:700 707.

5. McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL.

(1996). Exercise physiology: energy, nutri-

tion, and human performance, 4th edi-

tion. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

6. Moreau TP, Deeter M. (2005). Heat

strokepredictable, preventable, treat-

able. Journal-American Academy of

Physician Assistants, 18(8):30 35.

A more familiar method of determining

how hot it feels is the heat index which

factors the combination of temperature

and humidity (see Figure 1). Although

the heat index does not include the

eects of wind or radiant heat, it is a

good quantication of heat stress on the

body and is usually more readily avail-

able to the general public via the news

media (television, radio, and newspa-

pers).

Te cornerstone to treating HS is low-

ering the core temperature as rapidly

as possible (7). Chances of survival are

greatly improved if core temperature

can be lowered to under 38.9

o

C within

30 minutes (4). Rapid cooling can be

achieved in numerous ways including:

immersion in cold water or ice bath,

promoting evaporative heat loss (using

a fan), and the use of body cooling

suits. Other components of the acute

management stage (particularly in the

absence of medical personnel/facilities)

are calling 911, placing the person in

the supine position with feet elevated,

vigorous hydration, and maintenance of

an open airway. Excess clothing should

be removed and ice packs applied to the

neck, groin, and axillae (armpit) (3).

If the person is still outside, he or she

should be moved into the shade.

Te best defense against heat stroke and

other heat illnesses is prevention and

precaution. Te most important precau-

tion is to pay attention to heat warnings

issued by the National Weather Service

and limit or avoid exercise in danger-

ously hot conditions. Limiting direct

sun exposure is important because the

radiant heat can add up to 15

o

F to

the heat index (6). If exercise in the

heat is unavoidable, maintaining ade-

IntheGym

Joseph M. Warpeha, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

8

IntheGym

Joseph M. Warpeha, MA, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

7. Rhoades RA, Tanner GA. (2003).

Medical physiology, 2nd edition.

Baltimore: Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins.

About the Author

Joe Warpeha is an exercise physiologist

and strength coach and is currently work-

ing on his PhD in exercise physiology at

the University of Minnesota-Minneapolis.

His current research focuses on bone and

tendon adaptations to training and the

eects of skeletal loading on their physi-

ological and mechanical properties. Joe

teaches several courses at UM including

advanced weight training and condition-

ing and measurement, evaluation, and

research in kinesiology. He has a masters

degree in exercise physiology and certica-

tions through the NSCA, ACSM, USAW,

ASEP, and YMCA. He has over 14 years of

resistance and aerobic training experience

and has been a competitive powerlifter

since 1997. Joe is a two-time national

bench press champion and holds multiple

state and national records in the bench

press while competing in the 148, 165,

and 181-pound weight classes.

Figure 1. Calculation of heat index and associated risks of heat illness.

Reprinted with permission from the Oklahoma Climatology Survey

Oklahoma Climatology Survey. (2006). Heat Index Chart. Retrieved 2/21/06, from http://okfrst.ocs.ou.edu/train/materials/Heat/humid.gif

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

9

Ounceof Prevention

encing an injury due to running. Tis

article will feature a lower extremity

stretching program for the endurance

running athlete.

If you experience an injury related to

running, consult with your physician.

If appropriate, you may benet from

treatment and video running analysis

performed by a sports physical therapist.

R

unning is a popular sport

performed by individuals of

all skill levels. Athletes who

train for endurance races (5k or more)

may be at risk for certain lower extrem-

ity overuse injuries. Running athletes

should be aware of risk factors that may

contribute to the development of an

overuse injury.

Risk Factors

Training errors such as excessive changes

in mileage or training intensity, wear-

ing improper footwear, or running on

uneven surfaces may lead to stress frac-

tures, medial tibial stress syndrome,

muscle strains, Iliotibial band syndrome

(IT Band), or tendonitis (2).

Lack of exibility may contribute to

some muscle related running injuries. In

one study, researchers found that run-

ners tend to have tighter hamstring and

soleus (calf ) muscles than non-runners

(3).

Avoidance of training errors, maintaining

or improving exibility, and increas-

ing core and lower extremity strength

may help reduce your risk of experi-

Stretching

Current research recommends that you

perform your static stretching routine

at the end of a workout (1). When

stretching, ease gently into each stretch,

maintaining the hold for 30 seconds.

Holding each stretch for 30 seconds is

generally considered to be more benecial

than shorter time periods. Tis particu-

lar program does not promote the use of

ballistic (bouncing) stretching.

Lower Extremity Stretching

Program for Endurance

Runners

Jason Brumitt, MSPT, SCS, ATC, CSCS, *D

Figure 1. Hamstring Stretch

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

10

Hamstrings

Te hamstrings consist of 3 muscles

arising from the posterior portion of the

pelvis with attachments to the femur and

tibia. Stretching the hamstring muscles

can be performed in many positions.

When in a supine position, place a rope

(8 ft) around your foot and pull your

leg up while keeping your knee straight.

Try to pull your toes towards your face

(Figure 1). Te hamstrings may also be

stretched while sitting. As you lean for-

ward to increase the stretch, do so from

the hip versus rounding your low back

(Figure 2).

Piriformis

Tis muscle originates on the pelvis

(sacrum) and attaches to the femur. Te

Piriformis is often tight and painful in

athletes with low back or hip pain. Te

Piriformis can be stretched in multiple

positions. Lay on your back with knees

bent and one leg crossed over the other

(Figure 3). Pull your top knee across the

body towards the opposite shoulder. Te

Piriformis can also be stretched by plac-

ing one foot on the opposite knee and

pushing your top knee away from the

body (Figure 4).

Hip Flexor Stretching

Te Iliacus and Psoas Major are stretched

when you perform this exercise (Figure

5). Te Iliopsoas group arises from

the spine and pelvis and attaches on the

femur. Place your knee on the ground

slightly to the rear of the body. Te

other leg is in a 90-90 position. Lean

forward with the lead leg while main-

taining proper torso posture. Performing

an abdominal brace (gentle abdominal

isometric contraction) will help you to

maintain an upright torso. You will feel

the stretch in the anterior portion of the

hip or thigh of the back leg.

your foot toward your buttock (gure

6). If you are unable to maintain your

hip and back in alignment, use a towel

or rope around the ankle to assist with

knee exion.

Quadriceps

Te quadriceps (4 muscles) is made up

of the Rectus Femoris, Vastus Lateralis,

Vastus Medialis, and the Vastus

Intermedius. To eectively stretch this

muscle group, grab your foot, bringing

Ounceof Prevention

Jason Brumitt, MSPT, SCS, ATC, CSCS, *D

Figure 2. Sitting Hamstring Stretch

Figure 3. Piriformis Stretch

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

11

Calf

Te calf is made up of the deep soleus

muscle and the supercial gastrocne-

mius. Te gastrocnemius arises from the

femur while the soleus originates on the

tibia. Both muscles connect to the heel

bone (calcaneus) via the Achilles tendon.

Te classic runners stretch with the rear

leg extended stretches the gastrocnemius

(Figure 7), whereas bending the rear leg

at the knee increases the stretch on the

soleus (Figure 8). Each stretch should

be performed with shoes on and both

feet pointing forward.

Tensor Fascia Latae/ IT Band

Te IT band extends from the Tensor

Fascia Latae (TFL) muscle, running

along the lateral thigh and inserting at

the knee. To stretch the TFL stand next

to a wall and cross your outside leg over

the inside leg. Lean your hips toward the

wall making sure not to twist or arch the

back. You should feel a stretch down the

outside of your leg (Figure 9).

Conclusion

Te stretching program developed in

this article provides runners with a com-

prehensive exibility program for the

lower extremities (Table 1). A NSCA

certied strength and conditioning

specialist (CSCS) could provide individ-

ualized training recommendations based

upon ones exibility status.

References

1. Nelson AG, Kokkonen J, Arnall DA.

(2005). Acute muscle stretching inhib-

its muscle strength endurance perfor-

mance. Journal of Strength Conditioning

Research. 19(2): 338 343.

3. Wang SS, Whitney SL, Burdett RG,

Janosky JE. (1993). Lower extremity

muscular exibility in long distance run-

ners. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports

Physical Terapy. 17(2): 102 107.

2. OToole ML. (1992). Prevention

and treatment of injuries to runners.

Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

Sep; 24(9 Suppl): S360 S363.

Ounceof Prevention

Jason Brumitt, MSPT, SCS, ATC, CSCS, *D

Figure 4. Piriformis Stretch 2

Figure 5. Hip Flexor Stretch

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

12

Ounceof Prevention

Jason Brumitt, MSPT, SCS, ATC, CSCS, *D

About the Author

Jason Brumitt is a board-certied sports

physical therapist employed by Willamette

Falls Hospital in Oregon City, OR. His cli-

entele include both orthopedic and sports

injury patients. He also serves as adjunct

faculty for Pacic Universitys physical

therapy program. To contact the author

email him at jbrumitt72@hotmail.com.

Figure 6. Quadriceps Stretch

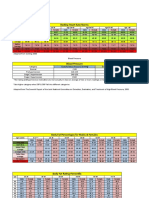

Table 1.

Stretching Program

Perform after running. Perform each stretch on

each leg

Calf

Soleus 2 x 30 seconds

Gastrocnemius 2 x 30 seconds

Quad Stretch 2 x 30 seconds

Hip Flexor Stretch 2 x 30 seconds

Piriformis 2 x 30 seconds

TFL 2 x 30 seconds

Hamstring 2 x 30 seconds

Figure 7. Gastrocnemius Stretch

Figure 8. Soleus Stretch Figure 9. TFL Stretch

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

13

Conditioning Fundamentals

A

ll children need to participate

regularly in physical activities

that enhance and maintain

cardiovascular and musculoskeletal

health. Traditionally, children have been

encouraged to perform aerobic activities

such as bicycling and strength build-

ing activities such as push-ups. More

recently, the potential benets of plyo-

metric training for youth have received

increased attention (2,3,4). Previously

thought of as a method of condition-

ing reserved for adult athletes, a grow-

ing number of trainers, teachers, and

youth coaches are now incorporating

plyometric training into their physical

education classes and sport conditioning

workouts.

Plyometrics were rst known simply

as jump training and refer to a type

of exercise that conditions the body

through dynamic, resistance exercise (1).

Plyometric training typically includes

hops, jumps, and medicine ball exer-

cises that exploit the muscles cycle of

lengthening and shortening to increase

muscle power. Plyometric exercises start

with a rapid stretch of a muscle (called

an eccentric muscle action) and are

If this window of opportunity is missed,

a child who does not participate in this

type of activity may not be able to catch

up later on in life. In the long run, this

child will be at a distinct disadvantage

when the time comes to participate in

more advanced training programs later

in life. Perhaps it is not surprisingly to

note that the best athletes in the world

learn how to perform complex skills

during childhood and adolescence.

Myths That Wont Quit

While clinical observations and research

ndings indicate that well-planned and

well-implemented plyometric training

programs can help youth develop move-

ment competence (2,4), some observers

still believe that plyometrics are inap-

propriate or even unsafe for children.

Unfortunately, some have a very narrow

view of plyometric training and only

associate drop jumps from a 32 inch box

as plyometric. While this high inten-

sity drill may be appropriate for highly

trained adult athletes, there are literally

hundreds of other plyometrics exercises,

including low intensity double leg hops

and throws with lightweight (1 to 2 kg)

medicine balls, which can be part of

followed by a rapid shortening of the

same muscle (called a concentric muscle

action). Te rapid stretching and short-

ening of a muscle during a plyometric

exercise is referred to as a stretch-short-

ening cycle. Even common playground

activities such as jumping jacks and hop

scotch can be considered plyometric

because the quadriceps at the front of

the thigh stretch eccentrically when the

child lands and then they shorten con-

centrically when the child jumps. Tese

exercises, although game-like in nature,

actually condition the body to increase

speed of movement and improve power

production.

Childhood may actually be the ideal time

to implement some type of plyometric

training program because the neuromus-

cular system of children is somewhat

plastic and can therefore readily adapt

to the training stress. Although adults

can certainly benet from plyometric

training, the so-called skill-hungry

years for learning motor skills occur

during childhood. As such, the nervous

system of children is primed to learn

motor skills that involve jumping, hop-

ping, skipping, running, and throwing.

Plyometrics for Kids:

Facts and Fallacies

Avery D. Faigenbaum, EdD, CSCS

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

14

a childs plyometric training program.

Other common myths associated with

youth plyometric training are discussed

below:

Myth: Youth who have not reached puber-

ty should not perform plyometrics.

Fact: Children can begin plyometric

training when they have the emotional

maturity to accept and follow directions.

As a point of reference, many seven and

eight year old boys and girls have partici-

pated in progressive plyometric training

programs over the years.

Myth: Children will experience bone

growth plate damage as a result of plyo-

metric training.

oer observable health and tness value

to most participants.

Program Design

Considerations

Plyometric training is a specialized

method of conditioning that requires

appropriate overload, gradual progres-

sion, and adequate recovery between

exercise sessions. Moreover, plyometric

programs should include proper coach-

ing, a safe training environment, and

a slow but steady advancement from

education to progression to function.

Since the performance of a plyometric

exercise is a learned skill, proper instruc-

tion is needed to ensure continuation of

correct exercise technique. Instructors

should be careful to match the plyo-

metric training program to the needs,

interests, and abilities of each child. An

advanced plyometric training program

for a young athlete would be inappro-

priate for an inactive child who should

be given an opportunity to experience

the mere enjoyment of dierent types of

hopping, jumping, and throwing exer-

cises. One of the most serious mistakes

in designing a youth plyometric train-

ing program is to prescribe a training

intensity that exceeds a childs capacity.

In short, it is always better to underes-

timate the physical abilities of a child

rather than overestimate them and risk

negative consequences (e.g., dropout or

injury).

Tere are literally hundreds of plyomet-

ric exercises that children can perform

depending on training experience and

ability. Children should begin with low

intensity drills (e.g., double leg jump or

medicine ball chest pass) and gradually

progress to higher intensity drills (e.g.,

lateral cone hop or single leg hop) over

Fact: A growth plate fracture has not

been reported in any prospective youth

resistance training research study which

was competently supervised and appro-

priately designed. Interestingly, some cli-

nicians believe that the risk of a growth

plate fracture in a prepubescent child

is actually less than in an older child

because the growth plates of younger

children may be stronger and more resis-

tant to shearing-type forces (5).

Myth: Plyometric training is unsafe for

children.

Fact: With appropriate supervision and

a sensible progression of training inten-

sity and volume, the risks associated with

plyometric training are not greater than

other activities in which children regu-

larly participate. Te key is to start with

a few simple exercises, provide qualied

supervision, perform these drills twice

per week on nonconsecutive days, and

gradually progressive as condence and

ability improve. Tis is especially impor-

tant for sedentary children who typically

have suboptimal levels of strength and

power.

Myth: Plyometric training is only for

young athletes.

Fact: Children of all abilities can benet

from plyometric training. While plyo-

metric exercises can be used to enhance

athletic performance and reduce the risk

of sports-related injuries, regular par-

ticipation in a plyometric program can

enhance the tness abilities of sedentary

boys and girls too. At a time when a

growing number of children spend more

time in front of the television than at the

playground, participation in a progres-

sive plyometric training program can

Figure 1. Double Leg Cone Hop

Conditioning Fundamentals

Plyometrics for Kids: Facts and Fallacies

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

15

time. In addition to body weight move-

ments, exercises using medicine balls

can also be eective. In terms of sets

and repetitions, beginning with one to

two sets of six to 10 repetitions on a

variety of upper and lower body exer-

cises twice per week on non-consecu-

tive days seems reasonable. If multiple

sets are performed, children should be

allowed to recover between sets in order

to replenish the energy necessary to

perform the next series of repetitions at

the same intensity. Unlike traditional

strength exercises, plyometric exercises

need to be performed quickly and explo-

sively. Te table highlights general youth

plyometric training guidelines.

Since plyometrics are not designed to

be a stand-alone program, youth con-

ditioning programs should include a

variety of skills and drills that are spe-

cically designed to enhance dierent

tness components. In fact, plyometrics

actually work best when integrated into

a multi-faceted program that includes

other types of training (2). Furthermore,

it is important for children to be exposed

to dierent types of conditioning and

actually understand the concept of a t-

ness workout. Combining tness com-

ponents is not only more eective and

time e cient, but this type of training

is more fun for young participants who

tend to dislike prolonged periods of

monotonous training. While there are

no short cuts or gimmicks to enhancing

strength, speed, and power, with guid-

ance and encouragement children will

gain condence in their abilities to per-

form relatively easy drills and therefore

they will be more willing and able to

perform at a higher level.

3. Faigenbaum A, Chu, D. (2001).

Plyometric training for children and

adolescent. ACSM Current Comment.

(www.acsm.org).

4, Hewett T, Myer G, Ford K. (2005).

Reducing knee and anterior cruciate

ligament injuries among female ath-

letes. Journal of Knee Surgery, 18(1): 82

88.

Summary

A growing number of children are now

experiencing the benets of plyomet-

ric training. In addition to enhanc-

ing fundamental tness abilities and

improving sports performance, regular

participation in a well-designed plyo-

metric training program may also reduce

the risk of injury in youth sports (2,4).

Whats more, plyometric training dur-

ing childhood may build the founda-

tion for dramatic gains in muscular

strength and power during adulthood.

With appropriate guidance and progres-

sion, plyometrics can be a worthwhile

additional to a well-rounded youth t-

ness programs that also includes aerobic,

strength, and exibility training.

References

1. Chu D. (1998). Jumping into

Plyometrics, 2nd ed. Champaign: Human

Kinetics.

2. Chu D, Faigenbaum A, Falkel, J.

(2006). Progressive Plyometric Training

for Kids. Monterey: Healthy Learning.

Conditioning Fundamentals

Plyometrics for Kids: Facts and Fallacies

Youth Plyometric Training Guidelines

Provide qualied instruction and supervision

Wear sneakers with tied laces and train on a nonskid surface

Begin each session with a dynamic warm-up

Start with one set of 6 to 10 repetitions on low intensity exercises

Develop proper technique on each exercise before progressing to more

advanced drills

Include exercises for the upper and lower body

Progress to 2 or 3 sets of 6 to 10 repetitions depending on needs, goals,

and abilities

Allow for adequate recovery between sets and exercises

Perform plyometric exercises twice per week on nonconsecutive days

Keep the program fresh and challenging by systematically varying the

training program.

Figure 2. Medicine Ball Chest Press

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

16

5. Micheli L. (1988). Strength training

in the young athlete. In E. Brown &

C. Branta (Eds.), Competitive Sports

for Children and Youth (pp. 99 105).

Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

About the Author

Avery Faigenbaum, EdD, CSCS, is an

Associate Professor in the Department of

Health and Exercise Science at Te College

of New Jersey. Dr. Faigenbaum is a leading

researcher and practitioner in the area of

youth tness and has authored ve books

and over 100 articles on youth strength

and conditioning. To contact the author,

email him at faigenba@tcnj.edu.

Conditioning Fundamentals

Plyometrics for Kids: Facts and Fallacies

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

17

use of this term (or similar terms such as

veried or certied) does not guar-

antee product quality or consistency.

On the other hand, if the FDA nds

a supplement to be unsafe once it is

on the market, only then can it take

action against the manufacturer and/or

distributor, such as by issuing a warning

or requiring the product to be removed

from the marketplace, as was the case

with coral calcium (often sold on late

night infomercials) and ephedra (which

was later reintroduced into the market).

Te Federal Government also regulates

supplement advertising, through the

Federal Trade Commission. It requires

that all information about supplements

be truthful and not mislead consumers.

As far as e cacy, unless the product is

covered by an approved FDA health

claim (such as calcium and osteoporosis

or ber and heart disease), to promote

its product, the manufacturer can say

that the product addresses a nutrient

deciency, supports health, or reduces

the risk of developing a health problem.

On the other hand, if the manufacturer

A

ccording to the National

Health Interview Survey,

Americans continue to take

dietary supplements at an increasing

rate, with 33.9% of US adults using a

vitamin and mineral supplement in the

past 12 months, up from 23.2% in 1987

and 23.7% in 1992 (5). According to

other research, 59% of elite athletes and

43% of college athletes, take supple-

ments. Multivitamins are the most fre-

quent type of nutritional supplements,

followed by vitamin C, iron, B-com-

plex vitamins, vitamin E, calcium, and

vitamin A (4). Many consumers report

using dietary supplements as insurance

for an inadequate diet, but also to pre-

vent or treat disease, increase energy

levels, or reduce the risk for infectious

illnesses (5).

With such high usage, one must gure

that the industry is a highly regulated

and safe market. Unfortunately, this is

not the case. Currently, the FDA regu-

lates supplements as foods rather than

drugs. In general, the laws about putting

foods (including supplements) on the

market and keeping them on the market

are less strict than the laws for drugs.

Many athletes are surprised to nd

out that manufacturers are not required

to prove a supplements safety or e -

cacy before the supplement is marketed.

Currently, the FDA does not analyze

the content of dietary supplements (see

below). At this time, supplement manu-

facturers must meet the requirements

of the FDAs Good Manufacturing

Practices (GMPs) for foods. GMPs

describe conditions under which prod-

ucts must be prepared, packed, and

stored. While food GMPs do not always

cover all issues of supplement quality,

some manufacturers voluntarily follow

the FDAs GMPs for drugs, which are

stricter. In addition, some manufac-

turers use the term standardized to

describe eorts to make their products

consistent. However, U.S. law does not

dene standardization. Terefore, the

TrainingTable

Sensible

Supplements

Debra Wein, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-CPT,*D

Whats in the Bottle Does Not Always Match Whats on the Label

A supplement might:

Not contain the correct ingredient (plant species). For example,

one study that analyzed 59 preparations of echinacea found that

about half did not contain the species listed on the label (1).

Contain higher or lower amounts of the active ingredient. For

example, an NCCAM-funded study of ginseng products found

that most contained less than half the amount of ginseng listed

on their labels

(2).

Be contaminated.

Source: National Center for Complimentary and Alternative Medicine (3)

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

18

does make a claim not approved by the

FDA, it must be followed by a state-

ment such as: Tis statement has not

been evaluated by the Food and Drug

Administration. Tis product is not

intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or pre-

vent any disease.

Choose sensibly. Supplements are meant

to do just thatto contribute to an

already healthy and well balanced eat-

ing plannot to make up for a poor

diet, Go to www.eatright.org to nd a

Registered Dietitian (RD) who can help

you choose supplements appropriate for

your performance and health goals.

References:

1. Gilroy CM, Steiner JF, Byers T, Shapiro

H, Georgian W. (2003). Echinacea and

truth in labeling. Archives of Internal

Medicine, 163(6):699 704.

2. Harkey MR, Henderson GL,

Gershwin ME, Stern JS, Hackman RM.

(2001). Variability in commercial gin-

seng products: an analysis of 25 prepa-

rations. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, 73(6):1101 1106.

3. NCCAM. (2003). Whats in the

Bottle? An Introduction to Dietary

Supplements. Retrieved February 17,

2005, from http://nccam.nih.gov/

health/bottle/.

4. Sobal J, Marquart LF. (1994).

Vitamins/mineral supplement use

among athletes: A review of the lit-

erature. International Journal of Sports

Nutrition, 4(4):320 334.

5. Tomson CA. (2005). Dietary supple-

ments, Journal of the American Dietetic

Association, 102(3):460 470.

About the Author

Debra Wein, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-

CPT,*D is on the faculty at Te University

of Massachusetts Boston and Simmons

College and is the President of Te Sensible

Nutrition Connection, Inc. (www.sensible-

nutrition.com). Debra has worked with

athletes and/or coaches of the United States

of America Track and Field Association,

National Hockey League, Boston Ballet

as well as numerous marathon training

teams.

TrainingTable

Debra Wein, MS, RD, LDN, NSCA-CPT,*D

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

19

Conditioning Fundamentals

T

here are many articles,

books, and videos on speed

and agility training. Many

of these resources overlook an extremely

important link in an athletes speed and

agility training; the ability to take the

rst few steps explosively.

Te ability to take the rst few steps

explosively is extremely important.

Tere are three major reasons for this.

First, the more explosively an athlete

can take the rst few steps, the better

potential he/she has to arrive somewhere

faster. Second, taking the rst few steps

explosively allows an athlete to get a step

on an opponent who is unable to take

the rst few steps as explosively. Finally,

in most cases an athlete only has a few

steps. With the exception of track events,

it is rare that an athlete can continuously

accelerate in a straight line for a hundred

meters. In most sports athletes are able

to accelerate over a short distance, then

they must stop or change directions.

Tis article is going to briey discuss the

factors that inuence the rst few steps,

it will cover technique on an explosive

start, progressions to learn the rst step,

provide several training tools, and will

ground. Maximal strength can be trained

through multi-joint strength training

exercises such as squats, Romanian dead-

lifts, and deadlifts.

Maximal strength is important, but it

also needs to be expressed quickly. Power

in conjunction with taking the rst

few steps explosively is trained through

plyometrics and variations of the clean,

snatch, and jerk.

Technique

When discussing proper technique for

the rst few steps, we should break this

down into two parts; the start and the

sprint.

The Start

Begin in the ready position. Feet are hip

width apart, weight is balanced over the

balls of the feet, the hips are pushed back

so that the center of gravity is low, and

the hands are held up to react to unex-

pected situations.

When the sprint begins, drive the pre-

ferred knee forward explosively (in this

article it will be the left knee). As the left

knee is driven forward the left arm will

be driven backwards, being swung from

conclude with a sample workout pro-

gram for dierent levels of ability.

Factors that infuence

A number of factors inuence the abil-

ity to take the rst few steps explosively.

Tese include proper starting and accel-

erating technique, ability to accelerate,

maximal strength, power, and reaction

time. All of these factors can be trained.

Technique always limits speed. Proper

technique will allow one to move explo-

sively, move his or her limbs quickly, and

prevent injuries cause by poor technique.

Technique is trainable through technical

drills that break down the entire move-

ment into its components and should

also be reinforced while sprinting.

Te rst few steps in a sprint involve

increasing velocity, which is called accel-

eration. Tis is trained through short

sprints (generally up to 20 yards) and

various acceleration training drills such

as stick drills, resisted starts, etc.

Maximal strength is important for over-

coming inertia at the start and for exert-

ing a large amount of force against the

Taking the First Few Steps

Explosively: Te Missing Link

John M. Cissik, MS, CSCS,*D, NSCA-CPT,*D

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

20

the shoulder. As the knee is being driven

forward, dorsiex (top of the foot up)

the left ankle so that it is approximately

at a 90 degree angle. Te combination

of these movements will cause a forward

lean, forming an angle with the ground.

It is important to stay low to the ground

during the rst few steps. Te left foot

will strike the ground close to the hips

and will make a pushing motion against

the ground (stay o the heel during

these sprints). Te pushing motion will

propel the body forward.

The Sprint

When leaving the start, focus on driv-

ing each knee forward, driving each arm

backwards (swinging from the shoul-

der), keeping the ankles dorsiexed, and

staying o the heels. Athletes should be

executing a pushing motion while they

are sprinting forward on the rst few

steps.

An extremely common error with short

sprints is to stand up too soon. When

this happens, athletes typically stand

straight up at the start and then attempt

to run forward with a pulling or paw-

ing motion. In a short sprint, this is a

bad idea for two reasons. First, pulling

or pawing too quickly will diminish the

athletes ability to accelerate. Second, if

the athlete is in a contact sport, stand-

ing up too soon (i.e. before contact) will

cause them to loose their balance when

they make contact with another athlete.

Learning technique

Starting and accelerating are both com-

plex skills that are not inherently known,

however they can both be learned. Tis

section will be divided into the same two

phases that were covered above.

The Start

Tere are three progressions that can be

used to learn explosive starts.

1. Falling starts: Face the direction of

the sprint. Feet should be no more

than hip width apart. Line the

toes of one foot up with the start

line. Te other foot will be placed

behind the front foot, so that the

toes of the back foot line up with

the heel of the front foot. Push the

hips back so that the body leans

forward and ex the knees slightly.

Te arms should hang down. From

this position gradually lift the hips

up, forcing the center of gravity

forward. As this happens you will

begin to fall forward. A natural

braking of the fall will occur by

stepping forward with the back

foot and driving the proper arm

backwards this should be the

beginning of the sprint. In other

words, you will fall into the sprint

with this drill.

2. Standing starts: Take the same

starting position described in the

falling starts. However, instead of

falling into the sprint, it will be the

deliberate motion described in the

technique section above (i.e. drive

the back knee forward, etc).

3. Crouching starts: Assume the same

foot position as described in the

falling starts drill. Te hips will

still be pushed back. In this drill,

the knees will be exed until you

are able to touch the ground with

both hands. Te arms will be kept

straight with the shoulders directly

in line with the hands. From this

position, begin the sprint by driv-

ing the back knee forward while

driving the proper arm backwards.

Figure 1. Arm Swing Drill

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

21

The Sprint

Tere are three categories of drills that

can be used to enhance acceleration

technique.

1. Arm swing drills (Figure 1): Arm

swing drills can be performed sit-

ting, standing, walking, or jogging.

Generally they are only benecial

for the rst one or two training ses-

sions. After that they should only

be used to correct errors. Tese

drills begin with one hand next

to the hip and one in front of the

shoulders. Both elbows should be

exed. When the drill begins, focus

on driving the hand in front of the

shoulder backwards towards the

hip. Focus on swinging the arm

from the shoulder. If the arm is

driven backwards properly then it

will move forward as a result of the

stretch reex at the shoulder and

chest, in other words, you should

not have to think about swinging

the arms forward.

2. Ankling drills (Figures 2 and 3):

Tese are performed as a walk or as

a bound. Ankling drills teach how

the foot should contact the ground

during sprinting. To perform this

drill, keep the legs straight and

move from the hips. As the hips

move forward, the back foot will

break contact with the ground.

As this happens the ankle should

be dorsiexed and should be kept

rigid. Te leg should be swung for-

ward from the hips so that the ball

of the foot lands on the ground in

front of the center of gravity.

3. High knee drills (Figure 4): Tese

can be performed as a walk, a skip,

or can be made more complicated

by combining them with move-

ments such as lunges. Tis teaches

the knee action during the sprint

and reinforces the correct position-

ing of the foot. Perform this drill

for the desired distance by focusing

on staying tall, lifting each knee in

front of the body until it is roughly

the height of the hip, and keeping

the ankle dorsiexed throughout

the drill. Remember to contact the

ground with the ball of the foot

placed slightly in front of the cen-

ter of gravity.

Training tools

A number of training tools can be used

to enhance the ability to take the rst

few steps explosively.

1. Starts: Performing sprints of up to

20 yards from a variety of starting

positions will enhance the ability

to start explosively and accelerate.

Starts can be performed from any

of the positions already described

Figure 2. Ankling Drill 1

Figure 3. Ankling Drill 2

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

22

in this article. In addition, other

positions can be used to train

starts, forcing more information

to be processed. Some examples

include performing starts with the

back to the course, from a shu e

(i.e. shu e, turn, sprint), from a

backpedal (i.e. backpedal, turn,

sprint), from the push-up position,

etc.

Starts can also be done in a resisted

fashion. In theory, more muscle

bers must be recruited during a

resisted explosive start and short

sprint, and this could transfer over

to sprints performed without resis-

tance. Resistance can be something

that weighs the athlete down (for

example, a sled, a tire, another

athlete, etc.) or could be a coach

or another athlete standing in

front of the sprinter and providing

resistance. It is very important that

good technique be emphasized and

required during resisted starts.

2. Stride length: Stride length drills

can help teach how to increase

stride length over the rst few steps

of the sprint. Generally miniature

hurdles or acceleration ladders are

used to train this. Tese are set

up so that each successive obstacle

is further away than the previous

obstacle. For example, six hurdles

may be set up so that they are: 18,

24, 30, 36, 42, and 48 apart.

3. Plyometrics: Plyometrics are impor-

tant for emphasizing the explosive

nature of the start. Appropriate

plyometrics include forward jumps

such as the standing long jump,

straight leg bounds, high knee

skips, and bounds.

4. Strength training: For starting

and accelerating, strength training

should focus on multi-joint lower-

body and total-body exercises. Core

training should also be performed

to help maintain good posture dur-

ing sprinting.

5. Combining tools: Tools can be

combined to save time and to

amplify their eects. For example,

plyometric and strength training

exercises can be combined.

Te rest of this article will present a

sample program for developing explo-

siveness over the rst several steps. Tree

levels will be presented; beginner, inter-

mediate, and advanced. Te exercises

become more complex, volume is added,

and the di culty of the program chang-

es between each level.

Being able to take the rst few steps

explosively is an important skill for most

athletes. Tis can be trained successfully

through the use of learning progres-

sion and by focusing on training tools

designed to enhance this quality. Taking

the time to address technique, accelera-

tion, maximum strength, and power can

help prevent injuries, keep the workouts

eective, and help to make the athlete a

more explosive one over short distances.

About the Author

John M. Cissik is the Director of Fitness and

Recreation at Texas Womans University.

John also operates a business, Fitness and

Conditioning Enterprises, that provides

speed and agility instruction primarily

to young athletes. John also consults with

track and eld teams regarding strength

training and track and eld.

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

23

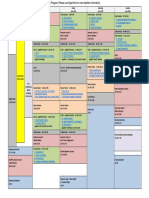

Beginner Program

Day One

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises, 10 15 minutes

Arm swing drills (seated, walking, jogging), 1 x 30 each

Ankling, 2 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 2 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 2 x 20 yards

Acceleration:

Falling starts, 3 x 5 yards

Standing starts, 3 x 20 yards

Strength:

Hang power clean from above the knee position, 3 x 3

Back squats, 3 x 8 12

Romanian deadlifts, 3 x 8 12

Core, 10 15 minutes

Day Two

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises, 10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 3 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Acceleration:

Stick drill from a falling start, 3 x 8 sticks

Standing starts, 3 x 20 yards

Plyometrics:

Standing long jump, 3 x 5, maximum efort

Strength:

Push Jerk, 3 x 3

Hang clean pulls from above the knee position, 3 x 4

Lunges, 3 x 8 12 each leg

Good mornings, standing, 3 x 8 12

Core, 10 15 minutes

Figure 4. High Knee Drill

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

24

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

Intermediate Program

Day One

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 1 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Stick drill from a falling start, 3 x 8 sticks

Acceleration:

Standing starts, 4 x 20 yards

Crouching starts, 5 x 20 yards

Strength:

Hang power clean from the knee position

+ Push Jerk, 3 x 3+2

Back squats, 3 x 8 12

Lunges, 3 x 8 12 each leg

Romanian deadlifts, 3 x 8 12

Core, 10 15 minutes

Day Two

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 1 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Speed:

Stride Length Drill, 20 yard sprint + mini

hurdles placed at 65%, 70%, 75%,

80%, 85%, 90% of optimal stride lengths,

3x

Plyometrics:

Standing long jump, 5 x 5 (maximum efort)

Standing long jump + 5 yard sprint, 5x

Vertical jump + 5 yard sprint, 5x

Day Three

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 1 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Stick drill from a falling start, 3 x 8 sticks

Acceleration:

Resisted standing starts, 5 x 20 yards

Starts, back to course, 3 x 20 yards

Starts, push-up position, 3 x 20 yards

Starts, shuf e + turn and sprint, 3 x 5 yards

(each direction)

Strength:

Hang power snatch from above the

knee position, 3 x 3

Front squats, 3 x 6 10

Back raises, 3 x 8 12

Core, 10 15 minutes

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

25

Conditioning Fundamentals

Taking the First Few Steps Explosively

Advanced Program

Day One

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Core training, 10 15 minutes

Strength:

Back squats, 3 x 2 4

Partial deadlifts (knee height), 3 x 2 4

Romanian deadlifts, 3 x 4 6

Day Two

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 1 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Stick drill from a falling start, 3 x 8 sticks

Power:

Power snatch + vertical jump + sprint,

3 x 3+1+5 yards

Split jerk + crouching start, 5 x 3+5 yards

Standing long jump + sprint,

3 x 1+10 yards

Behind back medicine ball toss + turn and

sprint, 3 x 1+10 yards

Day Three

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk + grab knee and hold,

3 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Speed:

Stride Length Drill, 20 yard sprint + mini

hurdles placed at 65%, 70%, 75%, 80%,

85%, 90% of optimal stride lengths, 3x

Day Four

WarmUp:

Dynamic fexibility exercises,

10 15 minutes

Ankling, 3 x 20 yards

Straight leg bounds, 3 x 20 yards

High knee walk, 1 x 20 yards

High knee skip, 3 x 20 yards

Stick drill from a falling start, 3 x 8 sticks

Speed:

Sport-specifc starts, 3 x 5 x 20 yards

Down and back agility drill, 3 5 x 25 yards

Box reactive agility drill, 3 5 x 10 seconds

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

26

What is success in practice?

In competition, success is about achiev-

ing your goal. Success may be winning

the race, setting a personal record, or

executing a specic task correctly. If

you are like most athletes, you know

exactly what you want to accomplish

in competition, and you see success

as achieving that goal. Practice should

be no dierent. Success in practice is

about achieving practice goals. If you

do not set goals for each practice, you

are not alone, but need to recognize

that daily goal setting is a necessary

rst step towards setting yourself up for

success in practice. You should have a

goal for every practice something you

want to accomplish. Even on those days

when you wish you were anywhere but

in practice, it is important to be able

to take something, however little it

may be, away from your training. As a

rst step, before every practice session,

ask yourself (and answer) the question

what am I going to work on today to

make myself better? Te answer to this

question, whether it is doing 30 minutes

of cardio, working on specic elements

of technique, or maintaining a positive

attitude, is your goal. Achievement of

this goal helps set the stage for practice

success.

Y

ou have heard the phrase

there are no guarantees in

life. Maybe you have heard

this when looking for some assurance

that the used car you just bought will

not break down, that you will do well

on an exam, or that your ight will be

on time so you can make your connect-

ing ight. While we plan for the best, it

is true that there are no guarantees. Te

same holds true in sport. Athletic success

is far too complex and multifaceted for

someone to be able to guarantee success

by following a simple set of guidelines.

Tere is always a chance that things will

not work out the way you would like

them to.

With that said, do not lose hope.

Fortunately, there are things you can

do to set yourself up for success and

increase your probability of success. In

this article, we are going to discuss

how to set the stage for success in prac-

tice. (A follow-up article in the next

NSCAs Performance Training Journal

will address strategies you can use to

increase the probability of success in

competition.) While we will obviously

focus on the mental aspects of training,

bear in mind that setting yourself up

for success also involves controlling

other aspects of performance such as

physical training, technical training, and

nutrition, to name a few.

Analyze Your Past

Whether you realize it or not, you

know better than anyone else what does

and does not work in regard to having

quality practice success. Take a minute

to identify strategies that seem to have

produced successful practices for you

in the past. Identify two to three things

you have found through experience that

you need to do to get the most out of

a given practice session. In doing so,

reect on your tendencies. For many

athletes, a pattern often exists in terms

of factors that have the greatest inuence

on success. For some, it may be having

the right energy level, whereas for oth-

ers going in with a positive attitude has

a critical inuence on practice. What

tends to get in your way when you have

a poor practice? What tends to help

performance?

If you are unable to identify any trends,

start the process of guring it out now.

Keep a practice journal and log informa-

tion about your practices that you think

could inuence your performance and

help (or hinder) you reach your practice

goals. How were you feeling during

the practice? What were you thinking

about? What did you eat and drink

before and during the practice? Did you

have an argument with your boyfriend

or girlfriend? How was your sleep? Start

Set Yourself Up For Success

In Practice

Suzie Tuey Riewald, PhD, NSCA-CPT,*D

MindGames

Suzie Tuffey Riewald, PhD, NSCA-CPT,*D

NSCAs Performance Training Journal | www.nsca-lift.org/perform Vol. 5 No. 2 | Page

27

logging this stu now and when you

look back over your records in a month

you will see the trends start to emerge.

Keep Baggage in Your

Locker

It is important to realize that you are

more that just an athlete. You may be

a student, a husband or wife, a brother

or sister, a friend, or simply a person

going through the ups and downs of life.

Tis means you have things going on

in your life besides your sport. You are

undoubtedly well aware of this as you

struggle to balance the various stresses

and responsibilities in your life and still

get something out of your training. But

how many times do negative thoughts

from other areas of your life encroach

on your practice? You can set yourself

up for practice success by leaving these

distracting thoughts away from the prac-

tice environment. Instead, keep this

baggage in your locker to be picked

up after practice. As you are putting on

your practice uniform or workout gear,

imagine you are putting on armor that

blocks all these negative thoughts and

allow you to focus on the task at hand.

Only when you take o the armor at

the end of the practice will your mind

be allowed to once again dwell on the

distractions from o the practice eld.

During practice, commit to physically

and mentally being an athlete and only

an athlete.

Control What You Say to

Yourself

You are the worst; I cant believe you

missed that lift.

Let it go. Focus on your breathing.

In reading these two self-talk statements,

you surely know which one is more

benecial to your performance versus

which would be more damaging. Being

overly negative, critical or unrealisti-