Introduction To Externalties

Diunggah oleh

Oladipupo Mayowa PaulJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Introduction To Externalties

Diunggah oleh

Oladipupo Mayowa PaulHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

INTRODUCTION TO EXTERNALTIES

This paper applies the microeconomic theory of demand and supply to analyse the different types of dimension of externalities with specific focus on the electricity market in Nigeria given ongoing reforms and the consequent role in the Nigerian economy in next few years. The work is basically divided into two sections, the overview of different types of externalities and the real application of demand and supply to electricity market in explaining these externalities. OVERVIEW OF EXTERNALITIES Externalities in Economics, is defined as the cost or benefit that is borne by a party that has not participated in the process of generating the cost or benefit. That is, externalities are the spillover effects from the actions of producers and consumers in a market on a third party who is not directly involved in the market as producers or consumer. According to About.com, externalities vary along two dimensions. First, externalities can be either negative or positive. Not surprisingly, negative externalities impose spillover costs on otherwise uninvolved parties, and positive externalities confer spillover benefits on otherwise uninvolved parties. (When analyzing externalities, it's helpful to keep in mind that costs are just negative benefits and benefits are just negative costs.) Second, externalities can be either on production or consumption. In the case of an externality on production, the spillover effects occur when a product is physically produced. In the case of an externality on consumption, the spillover effects occur when a product is consumed. Combining these two dimensions gives four possibilities.

Negative Externalities on Production

Negative externalities on production occur when producing an item imposes a cost on those not directly involved in producing or consuming the item. For example, factory pollution is the quintessential negative externality on production, since the costs of pollution are felt by everyone and not just those who are producing and consuming the products that are causing the pollution.

Positive Externalities on Production

Positive externalities on production occur when producing an item confers a benefit on those not directly involved in producing or consuming the item. For example, there is a positive externality on production in the market for fresh-baked cookies, since the (presumably pleasant) smell of baking cookies can often be experienced by people not involved in the baking or the eating of the cookies.

Negative Externalities on Consumption

Negative externalities on consumption occur when consuming an item actually imposes a cost on others. For example, the market for cigarettes has a negative externality on consumption because consuming cigarettes imposes a cost on others not involved in the market for cigarettes in the form of second-hand smoke.

Positive Externalities on Consumption

Positive externalities on consumption occur when there is a benefit to society of consuming an item above an beyond the direct benefit to the consumer of the item. For example, a positive externality on consumption exists in the market for deodorant, since wearing deodorant (and

therefore not smelling bad) confers benefits on others who are perhaps not themselves consumers of deodorant.

Because the presence of externalities makes unregulated markets inefficient, externalities can be viewed as a type of market failure. This market failure, at a fundamental level, arises because of a violation of the notion of well-defined property rights, which is in fact a requirement for free markets to function efficiently. This violation of property rights occurs because there are is no clear ownership of air, water, open spaces, and so on, even though society is affected by what happens to such entities.

When negative externalities are present, taxes can actually make markets more efficient for society. When positive externalities are present, subsidies can make markets more efficient for society. These finds are in contrast with the conclusion that taxing or subsidizing wellfunctioning markets (where no externalities are present) reduces economic welfare.

APPLICATION OF EXTERNALITIES IN THE NIGERIAN ELECTRICITY MARKET This section deals with the understanding of the spillover effects of externalities in the Nigerian electricity market. We examined the generation of electricity from the perspective of production such that we can xray the spillover effects of the power generating (GENCOs) firms in the value chain. It is imperative to

A Negative Externality of GENCOs in Electricity Market in Nigeria

A negative externality on production occurs when the production of a good or service imposes a cost on third parties who are not involved in the production or consumption of the product. Pollution is a common example of a negative externality on production, since pollution by a factory imposes a (non-monetary) cost on many people who otherwise have nothing to do with the market for the product that the factory creates.

When a negative externality on production is present, the private cost to the producer of making a product is lower than the overall cost to society of making that product, since the producer doesn't bear the cost of the pollution that it creates. In a simple model where the cost imposed on society by the externality is proportional to the quantity of output produced by the firm, the marginal social cost to society of producing a good is equal to the marginal private cost to the firm plus the per-unit cost of the externality itself. This is shown by the equation above. Cost of Production versus Cost to Society

Demand and Supply with a Negative Externality on Power Generation

In a competitive market, the supply curve represents the marginal private cost of producing a good for the firm (labeled MPC) and the demand curve represents the marginal private benefit to the consumer of consuming the good (labeled MPB). When no externalities are present, no one other than consumers and producers is affected by the market. In these cases, the supply curve also represents the marginal social cost of producing a good (labeled MSC) and the demand curve also represents the marginal social benefit of consuming a good (labeled MSB). (This is why competitive markets maximize the value crated for society and not just the value created for producers and consumers.)

When a negative externality on production is present in a market, the marginal social cost and the marginal private cost are no longer the same. Therefore, marginal social cost is not represented by the supply curve and is instead higher than the supply curve by the per-unit amount of the externality.

Market Outcome versus Socially Optimal Outcome in the Nigerian Power Sector

If a market with a negative externality on production is left unregulated, it will transact a quantity equal to that found at the intersection of the demand and supply curves, since that is the quantity that is in line with the private incentives of producers and consumers. The quantity of the good that is optimal for society, in contrast, is the quantity located at the intersection of the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost curves. (This quantity is the point where all units where the benefits to society outweigh the cost to society are transacted and none of the units where the cost to society outweighs the benefit to society are transacted.) Therefore, an unregulated market will produce and consume more of a good than is socially optimal when a negative externality on production is present.

Unregulated Markets with Externalities Result in Deadweight Loss

Because an unregulated market doesn't transact the socially optimal quantity of a good when a negative externality on production is present, there is deadweight loss associated with the free market outcome. (Note that deadweight loss is always associated with the suboptimal market outcome.) This deadweight loss arises because the market produces units where the cost to society outweighs the benefits to society, thus subtracting from the value that the market creates for society.

Deadweight loss is created by units that are greater than the socially optimal quantity but less than the free market quantity, and the amount that each of these units contributes to deadweight loss is the amount by which marginal social cost exceeds marginal social benefit at that quantity. This deadweight loss is shown in the diagram above.

(One simple trick to help find deadweight loss is to look for a triangle that point toward the socially optimal quantity.)

Corrective Taxes for Negative Externalities

When a negative externality on production is present in a market, the government can actually increase the value that the market creates for society by imposing a tax equal to the cost of the externality. (Such taxes are sometimes referred to as Pigouvian taxes or corrective taxes.) This tax moves the market to the socially optimal outcome because it makes the cost that the market imposes on society explicit to producers and consumers, giving producers and consumers the incentive to factor the cost of the externality into their decisions. A corrective tax on producers is depicted above, but, as with other taxes, it doesn't matter whether such a tax is placed on producers or consumers.

A Positive Externality on Production

Cost of Production versus Cost to Society

A positive externality on production occurs when the production of a good or service confers a benefit on third parties who are not involved in the production or consumption of the product. For example, Cinnabon creates a positive externality on production, since the smell of the cinnamon rolls confers a (non-monetary) benefit on many people who otherwise have nothing to do with the market for the product that Cinnabon creates. When a positive externality on production is present, the private cost to the producer of making a product is higher than the overall cost to society of making that product, since the producer doesn't incorporate the benefit of the externality that it creates. (If this doesn't immediately make sense, keep in mind that benefits are just negative costs.) In a simple model where the benefit conferred on society by the externality is proportional to the quantity of output produced by the firm, the marginal social cost to society of producing a good is equal to the marginal private cost to the firm minus the per-unit benefit of the externality itself. This is shown by the equation above. Supply and Demand With a Positive Externality on Production

In a competitive market, the supply curve represents the marginal private cost of producing a good for the firm (labeled MPC) and the demand curve represents the marginal private benefit to the consumer of consuming the good (labeled MPB). When no externalities are present, no one other than consumers and producers is affected by the market. In these cases, the supply curve also represents the marginal social cost of producing a good (labeled MSC) and the demand curve also represents the marginal social benefit of consuming a good (labeled MSB). (This is why competitive markets maximize the value crated for society and not just the value created for producers and consumers.)

When a positive externality on production is present in a market, the marginal social cost and the marginal private cost are no longer the same. Therefore, marginal social cost is not represented by the supply curve and is instead lower than the supply curve by the per-unit amount of the externality.

Market Outcome versus Socially Optimal Outcome

If a market with a positive externality on production is left unregulated, it will transact aquantity equal to that found at the intersection of the supply and demand curves, since that is the quantity that is in line with the private incentives of producers and consumers. The quantity of the good that is optimal for society, in contrast, is the quantity located at the intersection of the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost curves. (This quantity is the point where all units where the benefits to society outweigh the cost to society are transacted and none of the units where the cost to society outweighs the benefit to society are transacted.) Therefore, an unregulated market will produce and consume less of a good than is socially optimal when a positive externality on production is present.

Unregulated Markets with Externalities Result in Deadweight Loss

Because an unregulated market doesn't transact the socially optimal quantity of a good when a positive externality on production is present, there is deadweight loss associated with the free market outcome. (Note that deadweight loss is always associated with the suboptimal market

outcome.) This deadweight loss arises because the market fails to produce units where the benefits to society outweighs the cost to society and therefore doesn't capture all of the value that the market could create for society.

Deadweight loss arises from units that are greater than the market quantity but less than the socially optimal quantity, and the amount that each of these units contributes to deadweight loss is the amount by which marginal social benefit exceeds marginal social cost at that quantity. This deadweight loss is shown in the diagram above.

(One simple trick to help find deadweight loss is to look for a triangle that points toward the socially optimal quantity.)

Corrective Subsidies for Positive Externalities

When a positive externality on production is present in a market, the government can actually increase the value that the market creates for society by providing a subsidy equal to the benefit

of the externality. (Such subsidies are sometimes referred to as Pigouvian subsidies or corrective subsidies.) This subsidy moves the market to the socially optimal outcome because it makes the benefit that the market confers on society explicit to producers and consumers, giving producers and consumers the incentive to factor the benefit of the externality into their decisions.

A corrective subsidy on producers is depicted above, but, as with other subsidies, it doesn't matter whether such a subsidy is placed on producers or consumers.

A Positive Externality on Consumption Benefits of Consumption versus Benefits to Society

A positive externality on consumption occurs when the consumption of a good or service confers a benefit on third parties who are not involved in the production or consumption of the product. For example, playing music creates a positive externality on consumption, since, at least if the music is good, the music confers a (non-monetary) benefit on other people nearby who otherwise have nothing to do with the market for the music.

When a positive externality on consumption is present, the private benefit to the consumer of a product is lower than the overall benefit to society of consuming that product, since the consumer doesn't incorporate the benefit of the externality that he creates. In a simple model where the benefit conferred on society by the externality is proportional to the quantity of output consumed, the marginal social benefit to society of consuming a good is equal to the marginal

private benefit to the consumer plus the per-unit benefit of the externality itself. This is shown by the equation above.

Supply and Demand With a Positive Externality on Consumption

In a competitive market, the supply curve represents the marginal private cost of producing a good for the firm (labeled MPC) and the demand curve represents the marginal private benefit to the consumer of consuming the good (labeled MPB). When no externalities are present, no one other than consumers and producers is affected by the market. In these cases, the supply curve also represents the marginal social cost of producing a good (labeled MSC) and the demand curve also represents the marginal social benefit of consuming a good (labeled MSB). (This is why competitive markets maximize the value crated for society and not just the value created for producers and consumers.)

When a positive externality on consumption is present in a market, the marginal social benefit and the marginal private benefit are no longer the same. Therefore, marginal social benefit is not represented by the demand curve and is instead higher than the demand curve by the per-unit amount of the externality.

Market Outcome versus Socially Optimal Outcome

If a market with a positive externality on consumption is left unregulated, it will transact aquantity equal to that found at the intersection of the supply and demand curves, since that is the quantity that is in line with the private incentives of producers and consumers. The quantity of the good that is optimal for society, in contrast, is the quantity located at the intersection of the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost curves. (This quantity is the point where all units where the benefits to society outweigh the cost to society are transacted and none of the units where the cost to society outweighs the benefit to society are transacted.) Therefore, an unregulated market will produce and consume less of a good than is socially optimal when a positive externality on consumption is present.

Unregulated Markets with Externalities Result in Deadweight Loss

Because an unregulated market doesn't transact the socially optimal quantity of a good when a positive externality on consumption is present, there is deadweight loss associated with the free market outcome. (Note that deadweight loss is always associated with the suboptimal market outcome.) This deadweight loss arises because the market fails to produce units where the benefits to society outweighs the cost to society and therefore doesn't capture all of the value that the market could create for society.

Deadweight loss arises from units that are greater than the market quantity but less than the socially optimal quantity, and the amount that each of these units contributes to deadweight loss is the amount by which marginal social benefit exceeds marginal social cost at that quantity. This deadweight loss is shown in the diagram above.

(One simple trick to help find deadweight loss is to look for a triangle that points toward the socially optimal quantity.)

Corrective Subsidies for Positive Externalities

When a positive externality on consumption is present in a market, the government can actually increase the value that the market creates for society by providing a subsidy equal to the benefit of the externality. (Such subsidies are sometimes referred to as Pigouvian subsidies or corrective subsidies.) This subsidy moves the market to the socially optimal outcome because it makes the benefit that the market confers on society explicit to producers and consumers, giving producers and consumers the incentive to factor the benefit of the externality into their decisions.

A corrective subsidy on consumers is depicted above, but, as with other subsidies, it doesn't matter whether such a subsidy is placed on producers or consumers.

A Negative Externality on Consumption Benefits of Consumption versus Benefits to Society

A negative externality on consumption occurs when the consumption of a good or service imposes a cost on third parties who are not involved in the production or consumption of the product. For example, smoking cigarettes creates a negative externality on consumption, since secondhand smoke imposes a (non-monetary) cost on other people nearby who otherwise have nothing to do with the market for cigarettes.

When a negative externality on consumption is present, the private benefit to the consumer of a product is greater than the overall benefit to society of consuming that product, since the consumer doesn't incorporate the cost of the externality that he creates. (If this doesn't immediately make sense, keep in mind that costs are negative benefits.) In a simple model where the cost imposed on society by the externality is proportional to the quantity of output consumed, the marginal social benefit to society of consuming a good is equal to the marginal private benefit to the consumer minus the per-unit cost of the externality itself. This is shown by the equation above.

Supply and Demand With a Positive Externality on Consumption

In a competitive market, the supply curve represents the marginal private cost of producing a good for the firm (labeled MPC) and the demand curve represents the marginal private benefit to the consumer of consuming the good (labeled MPB). When no externalities are present, no one other than consumers and producers is affected by the market. In these cases, the supply curve also represents the marginal social cost of producing a good (labeled MSC) and the demand curve also represents the marginal social benefit of consuming a good (labeled MSB). (This is why competitive markets maximize the value crated for society and not just the value created for producers and consumers.)

When a negative externality on consumption is present in a market, the marginal social benefit and the marginal private benefit are no longer the same. Therefore, marginal social benefit is not represented by the demand curve and is instead lower than the demand curve by the per-unit amount of the externality.

Market Outcome versus Socially Optimal Outcome

If a market with a negative externality on consumption is left unregulated, it will transact aquantity equal to that found at the intersection of the supply and demand curves, since that is the quantity that is in line with the private incentives of producers and consumers. The quantity of the good that is optimal for society, in contrast, is the quantity located at the intersection of the marginal social benefit and marginal social cost curves. (This quantity is the point where all units where the benefits to society outweigh the cost to society are transacted and none of the units where the cost to society outweighs the benefit to society are transacted.) Therefore, an unregulated market will produce and consume more of a good than is socially optimal when a negative externality on consumption is present.

Unregulated Markets with Externalities Result in Deadweight Loss

Because an unregulated market doesn't transact the socially optimal quantity of a good when a negative externality on consumption is present, there is deadweight loss associated with the free market outcome. (Note that deadweight loss is always associated with the suboptimal market outcome.) This deadweight loss arises because the market produces units where the cost to society outweighs the benefits to society, thus subtracting from the value that the market creates for society.

Deadweight loss arises from units that are greater than the socially optimal but less than the market quantity, and the amount that each of these units contributes to deadweight loss is the amount by which marginal social cost exceeds marginal social benefit at that quantity. This deadweight loss is shown in the diagram above.

(One simple trick to help find deadweight loss is to look for a triangle that points toward the socially optimal quantity.)

Corrective Taxes for Negative Externalities

When a negative externality on consumption is present in a market, the government can actually increase the value that the market creates for society by imposing a tax equal to the cost of the externality. (Such taxes are sometimes referred to as Pigouvian taxes or corrective taxes.) This tax moves the market to the socially optimal outcome because it makes the cost that the market imposes on society explicit to producers and consumers, giving producers and consumers the incentive to factor the cost of the externality into their decisions.

A corrective tax on consumers is depicted above, but, as with other taxes, it doesn't matter whether such a tax is placed on producers or consumers.+

so it's important to understand these spillover effects and their impacts on economic value.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- 2 Estate Tax, Part 1Dokumen9 halaman2 Estate Tax, Part 1Kelvin CulajaráBelum ada peringkat

- Evergreen Corporation: Sti College Santa Rosa, LagunaDokumen16 halamanEvergreen Corporation: Sti College Santa Rosa, LagunaChristine Joyce Magote100% (1)

- DEFERRED TAXES: Calculating Expense, Assets & LiabilitiesDokumen5 halamanDEFERRED TAXES: Calculating Expense, Assets & LiabilitiesCris Joy BiabasBelum ada peringkat

- Court May Deny Injunction Without HearingDokumen7 halamanCourt May Deny Injunction Without HearingJovhilmar EstoqueBelum ada peringkat

- Filling Station GuidelinesDokumen8 halamanFilling Station GuidelinesOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Amcon Bonds FaqDokumen4 halamanAmcon Bonds FaqOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 9M 2013 Unaudited ResultsDokumen2 halaman9M 2013 Unaudited ResultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

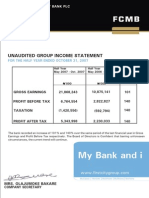

- FCMB Group PLC Announces HY13 (Unaudited) IFRS-Compliant Group Results - AmendedDokumen4 halamanFCMB Group PLC Announces HY13 (Unaudited) IFRS-Compliant Group Results - AmendedOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Abridged Financial Statement September 2012Dokumen2 halamanAbridged Financial Statement September 2012Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- q1 2008 09 ResultsDokumen1 halamanq1 2008 09 ResultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- IBT199 IBTC Q1 2014 Holdings Press Release PRINTDokumen1 halamanIBT199 IBTC Q1 2014 Holdings Press Release PRINTOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 9854 Goldlink Insurance Audited 2013 Financial Statements May 2015Dokumen3 halaman9854 Goldlink Insurance Audited 2013 Financial Statements May 2015Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Best Practice Guidelines Governing Analyst-Corporate Issuer Relations - CFADokumen16 halamanBest Practice Guidelines Governing Analyst-Corporate Issuer Relations - CFAOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- IBT199 IBTC Q1 2014 Holdings Press Release PRINTDokumen1 halamanIBT199 IBTC Q1 2014 Holdings Press Release PRINTOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- FCMB Group PLC 3Q13 (IFRS) Group Results Investors & Analysts PresentationDokumen32 halamanFCMB Group PLC 3Q13 (IFRS) Group Results Investors & Analysts PresentationOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- First City Monument Bank PLC.: Investor/Analyst Presentation Review of H1 2008/9 ResultsDokumen31 halamanFirst City Monument Bank PLC.: Investor/Analyst Presentation Review of H1 2008/9 ResultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 2007 Q2resultsDokumen1 halaman2007 Q2resultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- q1 2008 09 ResultsDokumen1 halamanq1 2008 09 ResultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Diamond Bank Half Year Results 2011 SummaryDokumen5 halamanDiamond Bank Half Year Results 2011 SummaryOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 2006 Q1resultsDokumen1 halaman2006 Q1resultsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- FirstCity Group profit up 88% in 3 monthsDokumen1 halamanFirstCity Group profit up 88% in 3 monthsOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Year Financial Report 2010Dokumen3 halaman5 Year Financial Report 2010Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 9-Months 2012 IFRS Unaudited Financial Statements FINAL - With Unaudited December 2011Dokumen5 halaman9-Months 2012 IFRS Unaudited Financial Statements FINAL - With Unaudited December 2011Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- GTBank H1 2011 Results PresentationDokumen17 halamanGTBank H1 2011 Results PresentationOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 5 Year Financial Report 2010Dokumen3 halaman5 Year Financial Report 2010Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 2011 Half Year Result StatementDokumen3 halaman2011 Half Year Result StatementOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- June 2009 Half Year Financial Statement GaapDokumen78 halamanJune 2009 Half Year Financial Statement GaapOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- GTBank FY 2011 Results PresentationDokumen16 halamanGTBank FY 2011 Results PresentationOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Final Fs 2012 Gtbank BV 2012Dokumen16 halamanFinal Fs 2012 Gtbank BV 2012Oladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Dec09 Inv Presentation GAAPDokumen23 halamanDec09 Inv Presentation GAAPOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- 2011 Year End Results Press Release - FinalDokumen2 halaman2011 Year End Results Press Release - FinalOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- GTBank H1 2012 Results AnalysisDokumen17 halamanGTBank H1 2012 Results AnalysisOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Fs 2011 GtbankDokumen17 halamanFs 2011 GtbankOladipupo Mayowa PaulBelum ada peringkat

- Standards of Conduct TrainingDokumen17 halamanStandards of Conduct TrainingCenter for Economic ProgressBelum ada peringkat

- NITI AAYOG ANNUAL REPORT Understanding the role and functioning of NITI AayogDokumen13 halamanNITI AAYOG ANNUAL REPORT Understanding the role and functioning of NITI AayogANKESH SHRIVASTAVABelum ada peringkat

- ACW2491 - 2018 S1 - WK 2 Lecture ExampleDokumen2 halamanACW2491 - 2018 S1 - WK 2 Lecture Examplehi2joeyBelum ada peringkat

- Vietnam Chapter - Real Estate Ma 2022 - Lexology Getting The Deal ThroughDokumen26 halamanVietnam Chapter - Real Estate Ma 2022 - Lexology Getting The Deal ThroughEric PhanBelum ada peringkat

- Netherby PLC Manufactures A Range of Camping and Leisure EquipmentDokumen2 halamanNetherby PLC Manufactures A Range of Camping and Leisure EquipmentAmit PandeyBelum ada peringkat

- c19 ProposalDokumen14 halamanc19 ProposalJonathanBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 07Dokumen27 halamanChapter 07Rollon NinaBelum ada peringkat

- The-Second-Conditional 2Dokumen3 halamanThe-Second-Conditional 2ana victoria fuentes palencia0% (1)

- Business Law PDFDokumen16 halamanBusiness Law PDFjtpBelum ada peringkat

- Exemptions from withholding tax on compensation under ₱90K and ₱250KDokumen2 halamanExemptions from withholding tax on compensation under ₱90K and ₱250KrjBelum ada peringkat

- Facility Location ModelsDokumen24 halamanFacility Location ModelsAbdullatif KarkashanBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 9 Financial ManagementDokumen18 halamanChapter 9 Financial ManagementAshish GangwalBelum ada peringkat

- Tax Assignment 4Dokumen5 halamanTax Assignment 4pfungwaBelum ada peringkat

- Tax Accounting Assignment Solution and ComputationDokumen10 halamanTax Accounting Assignment Solution and Computationsamuel debebeBelum ada peringkat

- Mutual Shoe Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 238 F.2d 729, 1st Cir. (1956)Dokumen7 halamanMutual Shoe Company v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 238 F.2d 729, 1st Cir. (1956)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Medical InsuranceDokumen1 halamanMedical InsuranceMasood AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- CR Report PDF For Board MeetingDokumen145 halamanCR Report PDF For Board MeetingCentral exchangeBelum ada peringkat

- Assignment: Multimedia University Cyberjaya CampusDokumen9 halamanAssignment: Multimedia University Cyberjaya CampusSree Mathi SuntheriBelum ada peringkat

- Government Borrowing From The Banking System: Implications For Monetary and Financial StabilityDokumen26 halamanGovernment Borrowing From The Banking System: Implications For Monetary and Financial StabilitySana NazBelum ada peringkat

- Urban Administration and Development Department Rewa Madhya Pradesh - 2032018113548416 PDFDokumen45 halamanUrban Administration and Development Department Rewa Madhya Pradesh - 2032018113548416 PDFAkshat MishraBelum ada peringkat

- Understand retail & wholesale profitsDokumen3 halamanUnderstand retail & wholesale profitsM.Faredhu HussainBelum ada peringkat

- Buc-Ee's Econominc Development Agreement With City of AmarilloDokumen20 halamanBuc-Ee's Econominc Development Agreement With City of AmarilloJamie BurchBelum ada peringkat

- Executive Order 1035 Streamlines Gov't Land AcquisitionDokumen5 halamanExecutive Order 1035 Streamlines Gov't Land Acquisitionahsiri22Belum ada peringkat

- Orbit BioscientificDokumen2 halamanOrbit BioscientificSales Nandi PrintsBelum ada peringkat

- 200645Dokumen100 halaman200645PGurusBelum ada peringkat

- 252289600057294Dokumen1 halaman252289600057294Pricila MercyBelum ada peringkat