Meara 1996 C

Diunggah oleh

Piyakarn SangkapanJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Meara 1996 C

Diunggah oleh

Piyakarn SangkapanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Meara 1996

The vocabulary knowledge framework. Paul Meara Swansea University INTRODUCTION One of the most influential papers in the canon of writing on vocabulary acquisition is Jack Richards' paper the role of vocabulary teaching (Richards !"#$% <hough this paper is now more than '( years old it continues to influence and inform research on vocabulary acquisition ) cf% for instance *llis ( !!+$, -chmitt and .eara ( !!"$ and -chmitt and .c/arthy ( !!"$% Richards' paper in effect set an agenda for much of this research, and though the themes it highlighted have been picked up, reordered and restructured by other writers (e%g% af 0rampe !123 4lum56ulka !1 3 .adden !1 3 7ation !!($, the basic concerns of this work remain remarkably similar to the ones that Richards catalogued% Richards' paper is concerned with what does it mean to know a word8 0o be fair, the theoretical issues which lie behind this deceptively simple question are not Richards' main interest% Rather he is concerned to work out how current thinking in linguistic theory might inform classroom practice% 9n spite of this, Richards' paper has been taken by some authors, including myself, as a sort of characterisation of word knowledge, and some decidedly theoretical research pro:ects have recently grown up with Richards' vocabulary knowledge framework as their foundation% Richards' himself is very cautious about linking pedagogical practice and research in this way; <%%% a consideration of recent work in theoretical or applied linguistics does not necessarily lead to discovery of new and e=citing ways to teach vocabulary% Rather it provides background information that can help us to determine the status of vocabulary teaching within the syllabus%< (p"1$% 0his caution has not always been followed by people who have adopted Richards' eight assumptions as a framework for describing vocabulary knowledge% 0his paper will first summarise and comment on the eight assumptions that form the main theoretical part of Richards' paper, and 9 will then go on to show why 9 don't think these assumptions make a good model of vocabulary knowledge% Richard ! eigh" a um#"ion $ and ome #roblem "hey rai e% Richards' article laid out a set of eight assumptions which characterise the relevant theoretical concerns of linguists at the time he was writing% 0hese assumptions are listed below% % 0he native speaker language continues to e=pand his vocabulary in adulthood, whereas there is comparatively little development of synta= in adult life% '% 6nowing a word means knowing the degree of probability of encountering that word in speech or print% >or many words, we also know the sort of words most likely to be found associated with the word% 2% 6nowing a word implies knowing the limitations imposed on the use of the word according to variations of function and situation% ?% 6nowing a word means knowing the syntactic behaviour associated with that word% +% 6nowing a word entails knowledge of the underlying form of word and the derivatives that can be made from it% 1

Meara 1996 #% 6nowing a word entails knowledge of the network of associations between that word and the other words in language (sic%$ "% 6nowing a word means knowing the semantic value of the word% 1% 6nowing a word means knowing many of the different meanings associated with the word% (p12$% 9t is easy to see how Richards' eight points arose directly out of research that was current in the mid5 !"(s% &ssumption one derives directly from work on @ acquisition which was suggesting that children had a largely complete grasp of the synta= of their @ by about the age of seven (/homsky !#!$% &ssumption two links to the beginnings of research on computational analysis of large corpora 55 the 6ucera and >ranis list, for instance, was published in !#", but work of this sort was beginning to have a significant impact on the way of linguists thought about grammar by the mid5 !"(s (6ucera and >rancis !#", -inclair !! $% -ignificantly, the /O4A9@B pro:ect dates from about this period% &ssumption three relates to current work in Register; Richards specifically mentions temporal variation, geographical variation, social variation, social role, field of discourse and mode of discourse, all topics which had recently attracted considerable attention in linguistics% &ssumption four is actually less all5 embracing in fact than it appears to be in the list above% Cere Richards is mainly concerned with a short5lived development in syntactic theory 55 case grammar 55 which faded shortly after Richards' paper appeared% 9nterestingly, recent linguistic theory has shown signs of return to grammatical models in which the syntactic properties of words are a more central concern (Cudson !1?$% Richards, however, was not aware of these future developments, and seems to be more narrowly concerned with the possibilities of case grammar% &ssumption five draws on the work of /homsky and Calle ( !#1$, and is principally an argument about the underlying regularity of morphological processes in *nglish from a phonological point of view% &ssumption si= picks up on the work of cognitive psychologists, notably Beese ( !#+$, who had attempted to e=plain word association behaviour in terms of a few simple relationships between words% &ssumption seven reflects two current approaches to descriptions of meaning% 0he first of these was a series of attempts to describe meaning in terms of fundamental semantic components (4ierwisch !"($% 0he second was an attempt to describe affective aspects of meaning by means of Osgood's semantic differential technique (Osgood, -uci and 0annenbaum, !+"$% &ssumption eight, unlike the others, does not appear to be based on any specific research, and clearly reflects what is, from the language teachers point of view, a gap in the research available at the time% 9t should be clear from this brief summary, that Richards' paper is not really an attempt to provide a systematic account of what it means to know word% &nd far less is it an attempt to provide a systematic framework for describing and accounting for this knowledge% Rather, it belongs to that other genre 55 an honest attempt to give an account of contemporary linguistic research with inferences and applications to teaching where appropriate% 9t is significant in this regard that more than half of Richards' paper is concerned with showing how current teaching practice can be :ustified by reference to the assumptions described earlier% 0hat is, the pedagogical practice is not derived from the research; it is already in place, but :ustified by the research in an ad hoc way% Once we realise that Richards' paper was not intended as a complete account of word knowledge in a second language, then number of things fall into place% >irstly, it e=plains why the list of assumptions contains these eight items, and conspicuously omits other aspects of word knowledge, which might have been important in other conte=ts% Dhat we have here is a short review of current themes in linguistics which might be relevant to vocabulary teaching% 9n fact, the listed topics will be familiar to anybody who has a copy of one of many anthologies of linguistic research which were published around the time the Richards was writing% @yons ( !"($, for instance, contains papers that touch on all eight of the assumptions in Richards' list% 2

Meara 1996 -econdly it e=plains the odd ordering the Richards' assumptions% 9t always surprised me that assumptions seven and eight 55 knowing a word means knowing the semantic value of word, and knowing many of the different meanings associated with it 55 should appear so low down the list of assumptions% 0hese two facets of word knowledge seen so crucial that we might have e=pected them to appear at the head of the list in letters four inches high% 9n comparison, facets of word knowledge such as assumption two 55 knowing whether word is frequent or not 55 seem to be much more peripheral% 0hirdly, treating Richards' paper as the review rather than as a formal statement about word knowledge, allows us to e=plain why the list of assumptions contains a number of obvious gaps% 0here is nothing in the list which relates in any obvious way to the problem of active versus passive vocabulary, for instance% 7or is there anything in the list which relates to vocabulary growth or to vocabulary attrition% 7or is there anything which relates to the conditions under which words are acquired, and so on% 9n short with the possible e=ception of item si= 55 the word association assumption 55 the list is driven e=clusively by the concerns of descriptive linguistics, rather than by psycholinguistic or pedagogical concerns% >inally, seeing the paper as a review allows us to e=plain Richards' puEEling use of the word assumptions to describe his eight statements% 9f the list of points was really intended as assumptions to be queried and probed, then a research programme might have emerged out of his paper% 9n fact, the statements are assumptions only in the sense that they form a background for the research reported% 7one of them is seriously questioned in this paper 55 and indeed it is difficult to see how any of them could be seriously ob:ected to, though each of them contains a large number of hidden problems which are the real but covert assumptions at the back of this paper% 4y way of an e=ample, let us try to unpack :ust one of the simple statements in Richards' list, assumptions #; knowing a word entails knowledge of the network of associations between that word and other words in the language% 0here are a number of hidden assumptions in this statement; a; each word in a language enters into a network of associations with other words in the language3 b; the resulting network is broadly similar for all speakers of a language3 c; it is possible for us to specify what this network is3 d; a speaker of the language knows the network (the use of know is problematical here$3 e; the network is fi=ed and stable3 f; the network of associations is a primary feature of a le=icon 55 rather than a secondary phenomenon which derives from some other, deeper structural property3 g; bilingual le=icons are not significantly different from the le=icons of monolingual speakers% &nd so on% 9t is clear from the short account, that assumption si= is not nearly as straightforward as it looks at first glance% & close look reveals a great deal of uncertainty, even muddle, in it, suggesting that the way le=icons were being thought about in this paper was very far from a coherent theoretical framework% <hough Richards was quite e=plicit about the pedagogical emphasis on his paper, this has not stopped other people from developing his ideas into a word knowledge framework 55 an attempt to characterise all the information that a fluent speaker might need to know about a word% 0his seems to me to be a rather unfortunate development% .y reason for reaching this conclusion is the Richards' model of word knowledge strikes me now as a peculiarly word5centred one% &t first sight, a word5 centred model of le=ical knowledge might not seem to be a bad thing% Obviously, one might argue, 3

Meara 1996 learners acquire a great deal of knowledge about individual words, and this knowledge needs to be codified and catalogued if we are to give a proper account of what it is the learners learn when they develop a competent @' le=icon% Dith the benefit of e=perience, this plausible argument strikes me as wrong% &nd worse than that, it is wrong in a way which forces into what can only be described as a research cul5de5sac% 0he logic of using Richards' statement as a framework is that it forces us to look more and more closely at knowledge of individual words% >or instance, the framework immediately turns a simple question like Boes F know >9-C8 into a much more comple= set of questions% Asing the word knowledge framework, we can rephrase our original question as; Boes F know the probability of encountering >9-C in print8 Boes F know the probability of encountering >9-C in speech8 Boes F know the limitations on the use of >9-C8 Boes F know the syntactic behaviour associated with >9-C8 Boes F know the derivations of >9-C8 Boes F know the network of associations linked to >9-C8 Boes F know the semantic value of >9-C8 Boes F know the different meanings of >9-C8 9 suppose that in an e=treme case it might be possible to devise a set of tests which could provide appropriate answers to these questions% 7ote, though, that if we are dealing with a word which has many different meanings, then the number of basic questions gets very large very quickly% >9-C, for e=ample, has at least four different meanings; the living animal, the flesh of the animal, the verb to fish, a children's card game, and so on% 0here is also a range of metaphorical e=tensions of these basic meanings, fishing for compliments, for instance or fishing for personal information on the 9nternet% &dd to this the derivatives of >9-C such as fishing, fishery, fisherman, and so on, and the task of describing what it means to know >9-C rapidly becomes an impossible one% 0esting all of these various aspects of word knowledge would require is to develop and administer a battery of ?( or +( tests, :ust to describe knowledge of a single vocabulary item% 0his is clearly out of the question for most practical purposes% Cowever, even if we could devise a battery of tests of this sort, we would inevitably find that many @ speakers and an even larger number of @' speakers failed on some parts of the test battery 55 partial knowledge of words seems to the norm in @ as well as in @'% 0hese problems clearly make things very difficult for the framework approach% 9f we e=tend the framework approach to a vocabulary of any siEe, say ((( words, then the sheer siEe of the measurement task makes the approach unworkable in real5life situations% 9f we work with smaller target vocabularies, then it is difficult to produce generalisations about le=ical competence in general% 9n any case, the fact that speakers will typically not know all that there is to know about a word means that the framework approach ends up by disappearing up its own assumptions, as it were; it is difficult to see how it can avoid making more and more detailed statements about fewer and fewer words% %ome al"erna"ive "o "he word knowledge framework 9s there a way out of this impasse8 9 think there are two main alternatives to the vocabulary knowledge framework% 0he first alternative is to abandon the attempt to describe knowledge of individual words altogether% 0his rather drastic solution was one which 9 advocated in .eara !!#% 9 suggested there that the task of specifying everything that learners know about the contents of their @' le=icons was intrinsically impossible, but it might be possible to simplify the problem% 9nstead of looking at individual words, it 4

Meara 1996 might be possible to look at the properties of a le=icon as a whole% Obviously, in practice, this would have to be done by testing individual words, but it might be possible to reduce what needed to be tested to a small number of significant dimensions% .eara !!#b suggested that three dimensions might be enough to give a rich categorisation of learners' le=ical competence% De would need to be able to specify how big the learners' le=icons are3 we would need to be able to specify how automatically the items in a le=icon could be accessed3 and we would need to find a simple measure of how rich a le=ical structure linked the words in the le=icon% -o far only the first of these dimensions has been studied in any depth (.eara !!?3 7ation !!(3 Goulden, 7ation and Read !!($% -ome preliminary work on le=ical structure has been published (Read !!23 Hives 4oi= !!+$, and some very e=ploratory work on automaticity is also beginning to appear (-egalowitE, Datson and -egalowitE !!+3 .eara !!#$, but a great deal of work on practical models and le=ical competence still remains to be carried out% 0he second alternative to Richards' framework is one which has been hinted at many times in the research literature, but never really developed% Anlike the dimensions approach outlined above, this approach is word5centred, rather than learner5centred, but it does not attempt to describe or account for the detailed linguistic properties of words% Rather, it attempts to identify a number of stages through which all words pass on their way to being fully integrated into a speaker's le=icon% .odels of this sort are often implicit in work on second language le=ical acquisition, but they are not often fully elaborated% Dhere they are elaborated, the underlying metaphor is usually some sort of continuum% & typical e=ample of this sort of model is to be found in Ialmberg ( !1"$% 9n this paper, Ialmberg developed a rather comple= metaphor about vocabulary learning as a hill which can increase in both height and area, and then wonders; Jualitatively, we may study first, how far individual words move along the continuum, and how fast they move as far as they go% 0o put it differently, are there transitional stages of learning through which learned words pass, and if so are these stages identifiable%%%8 &ssuming that such stages do e=ist%%% are there any clear thresholds of the type active threshold and passive%%% that words must cross before they can be considered to be properly learned%%%8 Bo all words, given time, pass from recognition knowledge to active production, or do some words remain forever passive%%%8 Bo words become fully integrated into the learner's mental le=icon only gradually%%%or can they :ump straight into active production from having been heard and correctly understood by the learner for the very first time%%%8 9f so under what conditions is this possible8 p'(2% <hough the continuum idea is a plausible one at first sight, it turns out to be much less satisfactory when e=amined closely% 0he main problem with it is that a continuum by definition implies at least one dimension which varies continuously, and it is by no means obvious what this dimension might be in the case of words% .any writers, including Ialmberg, talk quite glibly about the passiveKactive continuum, for instance, but is very difficult to imagine how a continuum might be an appropriate model for vocabulary% Dhat varies, and how does this variance produce the required effects8 .y own feeling is that the transition from passive to active is definitely not a continuum but is a clear candidate for a threshold effect, and it is not difficult to develop plausible theoretical accounts of vocabulary development which make this quite e=plicit (see for e=ample .eara !!($% Dhether there are degrees of passiveness, or degrees of activeness within these two broad states is not at all clear, however% Ieople who have talked most about vocabulary continua have never really developed the idea beyond the very rough metaphor, and typically do not concern themselves with this level of detail% 0he idea that words pass through a number of discrete stages seems to be a much more promising one than the continuum idea% Cere again, though, little systematic research aimed at identifying these 5

Meara 1996 possible stages has been carried out% 0he two obvious candidates states 55 a passiveKreceptive state and an activeKproductive state ) play an important part in the pedagogical discussion about vocabulary teaching, but it is very difficult to find any systematic elaborations involving more comple= state models (cf% Daring !!! for a detailed discussion of this point%$ 0here are too main e=ceptions to this claim% 0he first e=ception is a series of papers by Desche and Iaribakht (e%g% !!#$ which developed the idea of a vocabulary knowledge scale% Desche and Iaribakht identify a scale consisting of five stages of vocabulary knowledge, and they suggest a set a short tests which might characterise where any particular word is positioned on the scale% 0he five states are defined as statements that learners might make about their knowledge of a particular word, but in the case of the more comple= statements, some evidence that the learner's claim is true is required% Desche and Iaribakht's stages are listed below; % '% 2% ?% +% 9 don't remember having seen this word before3 9 have seen is word before but 9 don't know what it means 9 have seen is word before and 9 think it means%%% 9 know this word% 9t means%%% 9 can use this word in a sentence e%g%%%%

<hough Desche and Iaribakht's scale includes five states, state one simply reflects no knowledge at all about word% 0his means that the effective scale is only four points% @ike the continuum idea, the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale appears more attractive at first glance than it does under close scrutiny% 0he main reason for this is that the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale, like the vocabulary knowledge framework we described earlier, is essentially concerned with describing what stages individual words pass through% 0he level of description here is a lot coarser than was the level of description in the framework model, and this makes the task of describing word knowledge considerably simpler% Only the very basic stages through which a word might pass are described, and no attempt is made to account for more detailed knowledge about a word that develops over time% Cowever, for a vocabulary of any siEe, describing word knowledge even at this level still remains a formidable task% Desche and Iaribakht's level five, for instance, requires the testee to write a sentence containing the target vocabulary item, and this sentence then has to be rated by a competent assessor% 0his severely limits the number of words that can be tested on any one occasion% 0o be fair, Desche and Iaribakht are well aware of these limitations; they argue that the purpose of the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale is not to estimate general vocabulary knowledge, but rather to capture the initial stages or levels in word learning which are sub:ect to self5report or efficient demonstration, and which are precise enough to reflect gains during a relatively brief instructional period%%% &n e=tension of the scale might presumably be used to e=plore (more detailed$ aspects of knowledge but if this were done with significant numbers of words, it would greatly reduce its administrative feasibility% p'"% & second problem with the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale arises from the fact that Desche and Iaribakht seem to view the five (or four$ states as a progression% & word in state five is reckoned to be more fully integrated than a word at stage three or stage four% 0here clearly 9- some sort of progression between state two and the other states, but the idea of a strict progression between states three, four and five is rather more difficult to substantiate% 9n fact, there is no reason for us to believe that these descriptors reflect a succession of stages; it is perfectly possible for learners to write sentences their correctly illustrate the use of a particular word, even when they do not know the word's meaning% &ll they have to do is reproduce the conte=t in which they first met the word, or reproduce a fi=ed e=pression which contains it% 0his suggests that level five does not necessarily follow level four, 6

Meara 1996 or even level three% -imilar problems also arise in the description of the earlier levels% & further problem is that the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale as described by Desche and Iaribakht implies that once a transition from one level to the ne=t has been completed it remains permanent% De all know, of course, that this is not the case in real life% .ost of us will have had the e=perience of looking up a word in a dictionary while reading a foreign language te=t, and thinking we understand what it means% 0he transient nature of this knowledge sometimes becomes apparent when we find ourselves looking at self same word again, often only a few minutes after the original look up took place% 0his suggests that word knowledge may be much more volatile than the continuum or stage models imply, and this in turn suggests that the basic problem with the Hocabulary 6nowledge -cale is the idea of a progression through a series of well5defined stages% Dhat happens if we abandon the idea of a progression, and think instead of a number of states which are functionally independent8 -uppose for e=ample, that we take Desche and Iaribakht's five states and set up a model like the one shown in figure one8% &igure '( a mul"i "a"e model of vocabulary ac)ui i"ion

Anknown words start off in -tate (% 6nown words can be in a number of different states (here five$% & word in any state has a measurable chance of moving to another state during the given time period% 9f these probabilities can be assessed for a particular learner, then we can predict long5term development in the overall structure of the learners let you come% 9n this model we have five discrete states, and we allow words to move from any one state to any other state% 0hat is, it is possible for a word to move directly from -tate ( (9 do not know this word$ to -tate + (however this is defined$ in a single move% 9t also possible for words to move from any of the higher states back into -tate ( or any of the intermediate states 55 that is, a model of this sort allows learners to forget words that they know% &t first sight, this type of model looks inordinately comple=% Cowever, although the conditions under which these transitions might occur are not well5defined from a theoretical point of view, in practice we can sometimes work out the probability of words moving from one state to another for a particular learner in a particular set of circumstances%

Meara 1996 -ome work of this sort has been reported by one of my students (.eara and RodrLgueE -MncheE !!2$% using a series of models like the one >igure % Cis models typically used four states, which can be readily identified by the learners we worked with% Ce asked them to classify a large number of words into one of these four categories using a simple rating scale ) a task which the testees were able to complete in a very short time% & second test two weeks later with the same words showed that the words did not always remain the same category% 9n fact, a large number of words changed category over the two week testing period; some words that were known at 0ime were apparently forgotten the 0ime '3 other words not known or only partly known that 0ime moved to a higher category during the same period% >ar from being stable, the vocabularies of the learners we tested showed a very high degree of flu= and change, particularly where less frequent words were concerned% RodrLgueE -MncheE was able to use these data to calculate the probability of words moving from one state to another between the two tests% &ssuming that these probabilities were relatively stable over longer periods, he was then able to predict long5term distribution of words in a large target vocabulary across the four states 5 long5term here means ?# months%$ 9n many cases, these predictions were spectacularly successful; see for e=ample the data in >igure ', which illustrates how accurately a matri= model can make long5term predictions about vocabulary growth in a single sub:ect% 0he data comes from a study in which an empirically derived transitional probability matri= like the one in >igure was used to make a long5term prediction of the distribution of words from a ((( word target vocabulary into four discrete categories (light shading$% 0he dark shading shows the results of a real test taken some months later% 0he close correspondence between the prediction and the the actual data is very striking indeed% &igure *. #redic"ion from a ma"ri+ model( di "ribu"ion of word among four ca"egorie $ #redic"ed ver u ac"ual for one %ub,ec".

800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 1 2

state

RodrLgueE -MncheE's work suggests that discrete state models and probabilistic measures of how likely words are to move between a number of defined states hold a great deal of promise% Anlike the unidimensional continuum models, or Desche and Iaribakht's fi=ed progression scale, RodrLgueE -MncheE's models seem to be capable of generating predictions about the way whole vocabularies can develop or decline% De have been using them, for e=ample, to investigate the way that advanced 8

Meara 1996 learners' knowledge of @' vocabulary grows very rapidly during a period spent abroad, but then goes into a slow decline once the students return home, and are no longer e=posed to the target language for a significant part of the working day% 9t is important to note, though, that this predictive power is achieved at a price% RodrLgueE -MncheE's models rely on a matri= of transitional probabilities between the states of his model% <hough in principle it would be possible to design models which were made up of more than four states, with bigger, more comple= models would need to test many more words before we get reliable estimates of the transitional probabilities between states% Dith our four state models, we can get testees to rate about 2(( words, a task which is :ust about possible since the rating task does not require very much time% & more comple= model, say a ( state model, would require a much larger number of words to be tested if we wanted reliable transitional probabilities between the states% & further problem is that all the words are able to move from one state to another according to these probabilities, and this means that while we can predict the overall distribution of words in a particular @' learner's le=icon, these predictions describe what happens to the le=icon as a whole, not what happens to the individual words that make it up% 9n other words, RodrLgueE -MncheE's work involves a shift away from individual words in favour of a more global description about how le=icons grow and develop% 0his of course, is very same shift as the one we described in our first alternative to Richard's vocabulary knowledge framework, where we tried to reduce the idea of le=ical competence to a small number of significant dimensions% 0he generalisation here seems to be that we may not be able to pursue both a detailed analysis of word knowledge and make sensible statements about global aspects of le=icon competence at the same time% CONC-U%ION% 9n this paper 9 have discussed a number of different approaches to modelling what goes on when people acquire words in a second language% & very large part of this work is concerned are trying to provide detailed descriptions of how individual words get integrated into an @' le=icon% 9deally, this work would like to provide a complete account of how words move from wholly unfamiliar sequences of letters or sounds to become functional units in an effective le=icon% <hough this seems like a very laudable aim, 9 have argued here here that there is serious problem with the type of research that these aims generate% 0hey seem to force us to focus more and more on the ever finer details of le=ical knowledge, at the e=pensive of a deeper understanding of the global features of le=icon competence% 9t seems to me that the best future for research and vocabulary does not lie in pursuing detail at this level% Dhat really need is not so much a more detailed understanding of word , but rather a very much deeper understanding of le+icon % 0he area that we work in seems to one where the whole is considerably more interesting than the sum of its parts% 0he problem with some current models, 9 believe, is that they are in danger of losing sight of the wood through concentrating too hard on the individual trees%

R.&.R.NC.% af Tram#e$ P. !12 >oreign language learning 55 a criterion of learning achievement% 9n; / Ringbom (*d%$ Psycholinguistics and foreign language learning. Nbo; Nbo &kademi% 0ierwi ch$ M% !"(% -emantics% 9n; 1 -yon (*d%$ New Horizons in Linguistics% Carmondsworth; Ienguin 4ooks% 9

Meara 1996 0lum23ulka$ %. !1 % @earning to use words; acquiring semantic competence in a second language% 9n; M Nahir (*d%$ He rew teaching and applied linguistics% 7ew Oork; Aniversity Iress &merica% Chom ky$ C. !#!% !he "c#uisition of Synta$ in %hildren from &ive to !en% /ambridge, .ass%; .90 Iress% Chom ky$ N and M /alle% !#1% !he Sound Pattern of 'nglish% 7ew Oork; Carper Row% Dee e$ 1. !##% !he Structure of "ssociations in Language and !hought% 4altimore; John Copkins Iress% .lli $ R. !!+% .odified oral input and the acquisition word meanings% "pplied Linguistics #,?( !!+$, ?( 5?? % 4oulden$ R I%P Na"ion and 1 Read. !!(% Cow large can a receptive vocabulary be8 "pplied Linguistics ( !!($, 2? 52#2% /ud on$ R5% !1?% (ord )rammar. O=ford; 4lackwell% 3ucera$ / and N6 &ranci . !#"% !he %omputational "nalysis of Present*day "merican 'nglish% Irovidence, R%9%; 4rown Aniversity Iress -yon $ 1% (*d%$ !"(% New Horizons in Linguistics% Carmondsworth; Ienguin 4ooks% Madden$ 1&. !1(% Beveloping pupils' vocabulary skills% )uidelines 2( !1($, 5 "% Meara$ PM% !!(% & note on passive vocabulary% Second Language +esearch #,'( !!($, +(5 +?% Meara$ PM. !!?% 0he comple=ities of simple vocabulary tests% 9n; &4 0rinkman$ 15 van der %chee and MC7 %chou"en2van Parreren% (*ds%$ %urriculum research, different disciplines and common goals% &msterdam; 9nstituut voor Bidaktiek en Onderwi:spraktiek% Meara$ PM. !!#% 0he dimensions of le=ical competence% 9n; 4 0rown$ 3 Malmk,aer and 1 6illiam (*ds%$ %ompetence and Performance in Language Learning. /ambridge; /ambridge Aniversity Iress% Meara PM. !!#b 0he third dimension of le=ical competence% Iaper presented at the &9@& /ongress% JyvPskylP% Meara$ PM and I Rodr8gue9 %:nche9. !!2% .atri= models and vocabulary acquisition; an empirical assessment% %+'"L Symposium on -oca ulary +esearch% Ottawa% Na"ion$ I%P% !!(% !eaching and Learning -oca ulary% 4oston; Ceinle and Ceinle% O good$ C.$ 41 %uci and P/ Tannenbaum% !+"% !he .easurement of .eaning% Arbana 9ll%; Aniversity of 9llinois Iress, Palmberg$ R. !1"% Iatterns of vocabulary development in foreign language learners% Studies in Second Language "c#uisition !,'( !1"$, '( 5''(% Read$ 1. !!2% 0he development of a new measure of @' vocabulary knowledge% Language !esting (,2( !!2$, 2++52" % Richard $ 1C. !"#% 0he role of vocabulary teaching% !'S/L 0uarterly (, ( !"#$, ""51!% %chmi""$ N and M McCar"hy (*ds%$ !!"% -oca ulary, description, ac#uisition and pedagogy% /ambridge; /ambridge Aniversity Iress% %chmi""$ N and PM Meara% !!"% 10

Meara 1996 Researching vocabulary through a word knowledge framework; word associations and verbal suffi=es% Studies in Second Language "c#uisition !( !!"$, "52+% %egalowi"9$ N$ 7 6a" on and % %egalowi"9. !!+% Hocabulary skills; single case assessment of automaticity of word recognition in a timed le=ical decision to us% Second Language +esearch ,'( !!+$, "52+% %inclair$ 1. !! % Looking Up. @ondon; /ollins% 7ive 0oi+$ 4% !!+% "ssociation -oca ulary !ests. IhB thesis, Aniversity of Dales% 6e che$ M and % Paribakh"% !!#% &ssessing vocabulary knowledge; depth versus bread% /anadian .odern @anguage Review, +2, ( !!#$, 25?(% No"e . 0his discussion paper was first posted in !!#, and revised in 7ovember !!!%

11

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Worksheet Unit 3 Exploring Your Limiting BeliefsDokumen30 halamanWorksheet Unit 3 Exploring Your Limiting BeliefsCata lina100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Ap Chinese Scoring GuidelinesDokumen6 halamanAp Chinese Scoring Guidelinesapi-483317340Belum ada peringkat

- Evidence: Dr. Jose I. Dela Rama, Jr. Dean Tarlac State University, School of LawDokumen138 halamanEvidence: Dr. Jose I. Dela Rama, Jr. Dean Tarlac State University, School of LawSchool of Law TSUBelum ada peringkat

- Approaches and Methods in Language TeachingDokumen8 halamanApproaches and Methods in Language TeachingPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Learner Guide For Cambridge o Level Pakistan Studies Paper 1 2059Dokumen47 halamanLearner Guide For Cambridge o Level Pakistan Studies Paper 1 2059Umer Adnan90% (10)

- SELT Reading KrashenDokumen43 halamanSELT Reading Krashentrukson180% (5)

- I, You, He, She, It, We, They: GreetingDokumen20 halamanI, You, He, She, It, We, They: GreetingkrystenBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction to Philosophy of the Human PersonDokumen41 halamanIntroduction to Philosophy of the Human PersonDebby FabianaBelum ada peringkat

- An Analysis of Lexical Errors in The English Compositions of Thai LearnersDokumen23 halamanAn Analysis of Lexical Errors in The English Compositions of Thai LearnersPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Rod Ellis On Grammar#408437Dokumen25 halamanRod Ellis On Grammar#408437Sarah Gordon100% (2)

- Manual Ingles Nivel 2Dokumen95 halamanManual Ingles Nivel 2RogerBelum ada peringkat

- WTG PB5 Sample U8Dokumen12 halamanWTG PB5 Sample U8Elijah BayleyBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan RemedialDokumen7 halamanLesson Plan RemedialNur AskinahBelum ada peringkat

- Thailand 2016 GuideDokumen65 halamanThailand 2016 GuideSifat MazumderBelum ada peringkat

- 25 - Rules For Making ComparisonsDokumen2 halaman25 - Rules For Making ComparisonsMaria Jose Cermeno RodriguezBelum ada peringkat

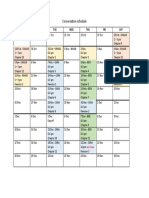

- Conversation Schedule: SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SATDokumen1 halamanConversation Schedule: SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SATPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Tesfl - Teaching Grammar PDFDokumen16 halamanTesfl - Teaching Grammar PDFPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Colorimetric and Fluorometric Detection of Cationic SurfactantsDokumen3 halamanColorimetric and Fluorometric Detection of Cationic SurfactantsPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- 94736Dokumen23 halaman94736Piyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8 Appearance PDFDokumen4 halamanChapter 8 Appearance PDFPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8 AppearanceDokumen4 halamanChapter 8 AppearancePiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Issues and Trends in Language Testing and Assessment in ThailandDokumen18 halamanIssues and Trends in Language Testing and Assessment in ThailandPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Heip, C. & Al. (1998) - Indices of Diversity and Evenness.Dokumen27 halamanHeip, C. & Al. (1998) - Indices of Diversity and Evenness.Carlos Enrique Sánchez OcharanBelum ada peringkat

- Umi Okstate 1041 PDFDokumen327 halamanUmi Okstate 1041 PDFPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Effekt Av Fettsyror Och Kolh P HDLDokumen10 halamanEffekt Av Fettsyror Och Kolh P HDLPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- 2009 - (MS) A Polydiacetylene Multilayer Film For Naked Eye Detection of Aromatic CompoundsDokumen6 halaman2009 - (MS) A Polydiacetylene Multilayer Film For Naked Eye Detection of Aromatic CompoundsPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Stimulate Recall2 PDFDokumen10 halamanStimulate Recall2 PDFPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Stimulate Recall PDFDokumen24 halamanStimulate Recall PDFPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Good Language Learner Traits S ThompsonDokumen31 halamanGood Language Learner Traits S ThompsonPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0346251X99000469 MainDokumen20 halaman1 s2.0 S0346251X99000469 MainPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- GCook HandoutDokumen2 halamanGCook HandoutPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Sensos 4 - Using Children's LitteratureDokumen17 halamanSensos 4 - Using Children's LitteraturePiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Sensos 4 - Using Children's LitteratureDokumen17 halamanSensos 4 - Using Children's LitteraturePiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Assessing Development of Advanced Proficiency Through Learner CorporaDokumen5 halamanAssessing Development of Advanced Proficiency Through Learner CorporaMario Molina IllescasBelum ada peringkat

- Brill - Toward A Science of Translating - 2013-07-06Dokumen1 halamanBrill - Toward A Science of Translating - 2013-07-06Piyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- Language Learning and TranslationDokumen6 halamanLanguage Learning and TranslationPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- EFL Learners Beliefs About Translation and Its Use As A Strategy in WritingDokumen10 halamanEFL Learners Beliefs About Translation and Its Use As A Strategy in WritingPiyakarn SangkapanBelum ada peringkat

- MachidaDokumen16 halamanMachidaPiyakarn Sangkapan100% (1)

- MachidaDokumen16 halamanMachidaPiyakarn Sangkapan100% (1)

- Anh 7 BAI TAP UNIT 6 A VISIT TO A SCHOOLDokumen15 halamanAnh 7 BAI TAP UNIT 6 A VISIT TO A SCHOOLcontact.maxographyBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching LiteratureDokumen10 halamanTeaching LiteratureIoana-Alexandra OneaBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge IGCSE™: Chemistry 0620/42Dokumen10 halamanCambridge IGCSE™: Chemistry 0620/42Shiaw Kong BongBelum ada peringkat

- Week 3 - Unit 5 Free TiimeDokumen5 halamanWeek 3 - Unit 5 Free TiimeKima Mohd NoorBelum ada peringkat

- The Exam ComprehensionDokumen4 halamanThe Exam ComprehensionLesleyBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge IGCSE ™: Biology 0610/62 October/November 2022Dokumen10 halamanCambridge IGCSE ™: Biology 0610/62 October/November 2022ramloghun veerBelum ada peringkat

- MUET writing task two essay on fashion and characterDokumen3 halamanMUET writing task two essay on fashion and character和 和了自己Belum ada peringkat

- Let's Focus On LearnersDokumen4 halamanLet's Focus On LearnersdowjonesBelum ada peringkat

- EACC 1614 - Test 1Dokumen7 halamanEACC 1614 - Test 1sandilefanelehlongwaneBelum ada peringkat

- Richmond Teacher S Book 4º Unit 3Dokumen15 halamanRichmond Teacher S Book 4º Unit 3ELENABelum ada peringkat

- NCERT Solutions Class 9 English Chapter 1 The Fun They HadDokumen9 halamanNCERT Solutions Class 9 English Chapter 1 The Fun They HadSHAKTI CHAUBEYBelum ada peringkat

- GET IELTS BAND 9 SpeakingDokumen54 halamanGET IELTS BAND 9 Speakingm.alizadehsaraBelum ada peringkat

- Methods of Collecting Primary Data (Final)Dokumen22 halamanMethods of Collecting Primary Data (Final)asadfarooqi4102100% (3)

- JACKSON V AEGLive June 10th Brandon "Randy" Phillips-CEO OF AEGLIVEDokumen139 halamanJACKSON V AEGLive June 10th Brandon "Randy" Phillips-CEO OF AEGLIVETeamMichael100% (1)

- Seminar 7 PETRONELA-ELENA NISTOR LMA EN-GEDokumen23 halamanSeminar 7 PETRONELA-ELENA NISTOR LMA EN-GEPetronela NistorBelum ada peringkat

- Spanish 2, Unit 5, Childrens Book ProjectDokumen2 halamanSpanish 2, Unit 5, Childrens Book Projectapi-263267469100% (1)

- Learning Outcomes: E-Commerce (CE52302-2) Individual Assignment Page 1 of 4Dokumen4 halamanLearning Outcomes: E-Commerce (CE52302-2) Individual Assignment Page 1 of 4Sasidhar ReddyBelum ada peringkat

- TEACHER WENDY BOHORQUEZ UltimoooDokumen9 halamanTEACHER WENDY BOHORQUEZ UltimoooGABRIEL URBANOBelum ada peringkat

- BL Prog Java Week 1 20 NewdocxDokumen216 halamanBL Prog Java Week 1 20 NewdocxJohn BikernogBelum ada peringkat

- Quiz F - N Set ADokumen77 halamanQuiz F - N Set AsrinivasanBelum ada peringkat

- Banaras Hindu University: 133 14thmay 2019 Shift 1 133 2019-05-14 13:50:11 150 450 Yes Yes YesDokumen73 halamanBanaras Hindu University: 133 14thmay 2019 Shift 1 133 2019-05-14 13:50:11 150 450 Yes Yes YesMd AdnanBelum ada peringkat