Ndepline Summer Fall12

Diunggah oleh

api-235820714Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Ndepline Summer Fall12

Diunggah oleh

api-235820714Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

NDEP-Line

From the Chair...

Patti Landers Professor and Internship Program Director University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Patti-Landers@ouhsc.edu

Summer/Fall 2012

In this issue:

NDEP Ofcers...................3 Establishing an International Community Nutrition Partnership...................4 2012 Preceptor Award Winners..........................4

All meaningful and lasting change starts rst in your imagination and then works its way out. Imagination is more important than knowledge. - Albert Einstein

NDEP has been in the business of promoting change for a long time. Last year we adjusted the name of our dietetic practice group (DPG) to better reect who we are. Instead of Dietetic Educators of Practitioners, we became Nutrition and Dietetic Educators and Preceptors (NDEP). Are you ready for more change? Merger into a better, more powerful organization is coming soon. As your chair, I represented NDEP at the Academys Board of Directors (BOD) meeting on Wednesday, October 10, just after the Food & Nutrition Conference and Expo (FNCE). Education Committee chair Deb Canter (also an NDEP member) and I were there to present the merger proposal and answer questions. The BOD will vote on the merger at their January meeting. Why was change needed? The EC has fewer than ten people and a long list of vital tasks to accomplish. NDEP has over 2,000 members a signicant workforce of members with big ideas who are willing to work hard. The two groups were duplicating efforts. By merging with the Education Committee, we can expedite initiatives that benet students, educators and the Academy. What will we gain? We will have an executive committee member who represents our interests to the BOD. We will also have closer ties to the

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation Grant.......7 Positioning Dietetic Interns and Students for Success in the Job Market............................7 Integrating Undergraduate Research into the Curriculum................. 10

2 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND) since we will have one FTE staff support from the Education Programs Team. Like a DPG, we will continue to elect our leadership. We will also continue to collect dues our members pay when they renew their Academy membership each year. This is needed to continue to fund the same things we have been doing as a DPG. We will continue the spring regional meetings, the newsletter, updating and publishing the annual Applicant Guide to Supervised Practice to aid students looking for internships. And of course we will build our initiative to publish articles related to education activities in the Practice Applications section of the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. I cannot think of anyone smarter than Albert Einstein. He said that imagination is more important than knowledge. Last year, NDEP voted to dissolve and become a new unit. That ship has sailed and there is no going back. As of May 31, 2013 NDEP will be history. The change to a new and better thing has started in our imaginations and is working its way out. It is going to take all of us to get this job done. Start thinking about where you will serve and the difference you can make as we create what Einstein called meaningful and lasting change. AREA MEETINGS Held in the Spring NDEP holds spring meetings throughout the country. These are a great place to earn CPEU credit, keep up with what is happening in the accreditation world (we have new Standards as of June 2012) and network with other educators and preceptors. There are seven area coordinators who are currently planning their meetings and details about dates and locations will be announced at the Member Reception and Meeting on Sunday at FNCE. Please be aware that ACEND (Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics) will be holding a training workshop for program directors in conjunction with one of our area meetings. There is not a pre workshop scheduled at FNCE this year. New people who need training will want to choose that area meeting to attend. We also hope to broadcast from one virtual meeting site this year for people who cannot attend a meeting, but want to get in on the CPEU credit and information. Conrmed Dates: Area 1 Meeting will be held on March, 17th, 18, and 19th Area 1 coordinator is Miriam Edlefsen Ballejos (medlefsen@wsu.edu). Area 2 & 5 Meeting will be held on March 21st & 22nd in St. Louis, MO. Area 2 coordinator is Katie Eliot (keliot@slu.edu) and Area 5 coordinator is Julie A Kennel (jkennel@ehe.osu.edu). Area 6 & 7 Meeting will be held on April 10th, 11th and 12th in Charlottesville, VA. Area 6 coordinator is Ana Abad Jorge (ara6t@virginia.edu) and Area 7 area coordinator is Suzanne Neubauer (sneubauer@framingham.edu). Area 3 & 4 Meeting will be held on April 19th and 20th in Birmingham, AL. Area 3 coordinator is Susan Miller (miller1@uab.edu) and Area 4 coordinator is Claudia W. Scot (claudiawscott@hotmail. com).

Patti

3 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

Guidelines for Authors for NDEP-Line

NDEP-Line features viewpoints, statements, and information on materials and products for the use of Nutrition and Dietetic Educators and Preceptors (NDEP) members. These viewpoints, statements and information do not imply endorsement by NDEP and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Articles may be reproduced for educational purposes only. NDEP-Line owns the copyright of all published articles, unless prior agreement was made. Copyright 2012 by Nutrition and Dietetic Educators and Preceptors, a Dietetic Practice Group of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means without permission of the publisher. n Article length Article length is negotiated with the managing editor for the issue in which it will appear. Lead articles are usually around 2,000 words. Other feature articles are 1,000-1,500 words while book reviews and brief reports are 500 words. n Text format All articles, notices, and information should be in Times New Roman font, 12 pitch, single space. n Tables and illustrations Tables should be self-explanatory. All diagrams, charts and gures should be camera ready. Each illustration should be accompanied by a brief caption that makes the illustration intelligible by itself. n References References should be cited in the text in consecutive order parenthetically. At the end of the text, each reference should be listed in order of citation. The format should be the same as that of the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. For example, a periodical would be cited as fol- lows (please note the absence as well as placement of periods): 1. Lavery MA, Loewy JW, Kapadia AS, Nishaman MZ,Foreyt BP, Gee M. Longterm follow-up of weight status of subjects in a behavioral weight control program. J Acad Nutr Diet 989;89:12591264. Italicize all web references, i.e., http://www. nhgri.nih.gov/Policy_and_public_affairs/ communic ations/Publications/Maps_to_ medicine/ A submission may be returned to the primary author for revision if it does not conform to the style requirements. n Author(s) List author with rst name, initial (if any) last name, professional sufx, and afliation (all in italics) below the title of the article, i.e., For NDEP members or other dietetic educators: Anne A. Anderson, PhD, RD, LD, American University For authors in other elds/disciplines Anthony T. Vicente, PhD, Director, Nutrigenomics Laboratory, American Human Nutrition Research Center on Genetics at American University

Authors Contact Information Before the article, give the primary authors complete contact information including program afliation, phone, fax and email address. Submission All submissions for the publication should be submitted to the editors on diskette or as an e-mail attachment as either an MS Word le or a text le. Indicate the number of words after authors contact. Submission deadlines Spring: January 30 Summer: April 30 Fall: July 30 Winter: October 30 Editor Dorothy Chen-Maynard, PhD, RD California State University, San Bernardino Phone: 909.537.5340 dchen@csusb.edu Reprint permissions request, back issue or advertisement Contact Patti Landers (Patti-Landers@ ouhsc.edu)

NDEP Ofcers:

Patti Landers Chair Patti-Landers@ouhsc.edu Rayane Abusabha Chair-Elect abuser@sage.edu Robyn A Osborn Secretary Osborn_robyn@yahoo.com Tina Shepard Treasurer Tina.shepard@asu.edu Vicky Getty Nominating Chair vgetty@indiana.edu Khursheed Navder Past Chair knavder@hunger.cuny.edu Miriam Edlefsen Ballejos Area 1 Coordinator medlefsen@wsu.edu Katie Eliot Area 2 Coordinator keliot@slu.edu Susan Miller Area 3 Coordinator Miller1@uab.edu Claudia W. Scott Area 4 Coordinator claudiawscott@hotmail.com Julie A Kennel Area 5 Coordinator jkennel@ehe.osu.edu Ana Abad-Jorge Area 6 Coordinator Ara6t@virginia.edu Suzanne Neubauer Area 7 Coordinator sneubauer@framingham.edu Dorothy Chen-Maynard Communication Chair dchen@csusb.edu Ruth Johnston Listserv Manager Ruth.Johnston@va.gov Vicky Getty Applicant Guide Chair vgetty@indiana.edu Mya Wilson Academy Liaison mwilson@eatright.org

n n

Advertising NDEP-Linewill accept advertisements only for position openings, products, and services of interest to NDEP members. Educational seminars will be advertised at no charge. The categories and rates for advertising are as follows: Corporate Advertising: Full page$500 Half page$300 Third page$240 Quarter page$175 Eighth page $90 Classied Advertising: 50-word limit, $25 per ad. NDEP members receive a 20% discount. Advertisements will be limited to seminars, publications, services, or products offered by companies, publishers, other Academy dietetic practice groups, or individual NDEP members. We prefer all logos and artwork be in electronic form, of high resolution and accompany the advertise ment copy. Make checks payable to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics NDEP (DPG 50) and mail to Patti Landers, 4401 Shoreline Drive, Norman, OK 73026-1310. Please list account 150-425-310-5010 on your check.

NDEP Website:

www.ndepdpg.org email Ruth.Johnston@va.gov to sign onto the NDEP ListServ, DEP-L@uams.edu

4 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

2012 Preceptor Award Winners

The 2012 Preceptor Award winners were announced at the FNCE NDEP members meeting, October 7, 2012. Area I: Samantha Maloney, MS RD CSP CNSC LD (Nominated by Melissa Chlupach MS RD) Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage, AK Preceptor for 16 years Area 2: Lisa McDowell, MS, RD, CNSD, CSSD (Nominated by Diane Reynolds, RD-Clinical Coordinator) Eastern Michigan University Preceptor for 16 years Area 3: Nancy Giles Walters, MMSc, RD, CSG, LD, FADA (Nominated by Jeanne B. Lee, MS, RD, LD- IP Director Augusta Area Dietetic Internship, Augusta, GA Preceptor for 23 years Area 4 Renee Walker, MS,RD,LD,CNSC (Nominated by Kristy Rogers, MS,RD,LD,CNSD) Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, Houston, TX Preceptor for 10 years Area 6 William Swan, RD, LDN (Nominated by Phyllis Fatzinger McShane, MS RD LDN) University of Maryland College Park, College Park, MD Preceptor for 10 years Area 7 Alice OConnor, MS, RD, LDN, CNSC (Nominated by Judy Dowd, MA, RD, LDN University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA Preceptor for 22 years

Establishing an International Community Nutrition Partnership

Erin Bergquist MPH,RD,LD,CNSC Clinician/Dietetic Internship Iowa State University

Five Iowa State University (ISU) Dietetics Interns had the experience of a lifetime last May when ISU Dietetics Internship (DI) partnered with University of Ghana and McGill University (Canada) to provide a 4 week optional community nutrition rotation outside of Asesewa, Ghana. Planning this experience was several years in the making, and consisted of strong partnerships with key academic institutions and

leaders. Dr. Grace Marquis of McGill University (former ISU faculty) was instrumental in introducing ISU to University of Ghanas Associate Professor Dr. Anna Lartey. ISU has a strong history of global partnerships and study abroad experiences, but incorporating optional international supervised practice experiences within the Dietetics Internship was a new experience. First steps in the process included getting the green-light from ISU Food Science and Human Nutrition Department

Chair and College of Human Sciences Dean and obtaining a Memorandum of Understanding with the University of Ghana (UG). Next, the DI received a grant to visit the UG Nutrition and Research Training Centre, where interns would be housed during this experience, in early 2011. A Major Change Request to include up to 200 hours of optional international supervised practice in the ISU DI was submitted to ACEND and granted in summer 2011.

5 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

After the site visit and many discussions with the UG Nutrition and Food Science Department, UG Dietetics Internship program, local dietitians, local hospital, and key leaders in the Asesewa community a rough plan was set into place. Over the course of the next year, through Skype, conference calls, and one face-to-face meeting in Canada, the internship experience was planned to the smallest detail. Activities included several meetings with key people in the community, including the hospital physician and administrator, local chief, local queen mother, mayor, and police chief; community focus groups; visit to the local market; Princess Marie-Louise Childrens Hospital; local mill; and local site seeing excursions. Applicants to the international community rotation completed the standard application requirements for ISU with an additional written essay and phone interview that assessed their potential for success in this opportunity. Situation-based questions addressed leadership skills, exibility, teamwork and critical thinking skills, along with physical and emotional demands of international travel. Once the interns were selected, health and ISU required preparation requirements were completed to ensure everyone was ready for travel and familiar with the location, usual diet, culture, and customs they were about to experience rst-hand. Planning the experience relied heavily on recommendations from the UG and local dietitians afliated with the Ghana Health Service, Ghanas government run health care system.

Consideration was given to allow for transportation time and rest, but for the most part, activity lled days kept the interns engaged in their surroundings and interacting with the Ghanaian and Canadian interns. Interns completed the programs capstone project titled, Technology in Health Promotion, which met the following competencies: CRD 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.9, 2.10. 3.1a,b,c,d,e, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 4.5, 4.6, 4.8, 4.10. As part of the project, interns practiced the Nutrition Care Process in two small communities in the Upper Manya Krobo district of Ghana, focusing on complementary feeding practices of breastfed infants ages 6 months to 2 years. The assessment data includes focus group discussions with community elders and leaders, research into health ndings and previous studies in similar areas of the region, a questionnaire (translators assisted interpretation), and anthropometric data gathering. Through this assessment, interns diagnosed the community with Food- and Nutrition-Related Knowledge Decit (NB-1.1) related to lack of previous exposure to accurate nutrition information as evidenced by 64% of children aged 6 months-2 years were consuming less than 4 food groups on a daily basis. To complete their intervention, interns gathered the village members in a durbar or health fair where they performed a skit demonstrating proper feeding practices and how to incorporate a variety of nutrients into daily diets. The durbar was a complete success with more than 70 village members attending and interacting with the interns. Interns

also formally presented their ndings to key leaders within the community and at the University of Ghana. Interns were evaluated using a variety of methods, including weekly evaluations, weekly reective blogs, and group projects. All in all, the experience was an enormous success with comments from interns, such as, After this experience, I learned my previous assumption that the NCP was only for clinical work was completely false, and now I can apply this process to help organize my thinking in any situationI have learned a lot about myself and really improved my teamwork abilitiesI have vastly improved my skills in communicating with people of different cultures through this experienceI now have the condence to deal with any situation, I am ready to head back to the U.S. and nail my rst job interview! Information obtained from this community experience will be used to assist in developing the next experience, scheduled this October November, 2012. Lessons learned and feedback will continually guide the program planning and improve classes, which are scheduled to continue biannually. Although the road to developing an international program can be long, lessons provided can be timeless. Through this experience, ISU DI can conclude that international experiences provide students with a more intensive experience than can be expected through local placements in the U.S., thus stimulating the students creativity, building

6 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

their knowledge about the steps in assessing and developing approaches to problems in health, and expanding their condence to be able to be successful in their future career.

ISU Intern Ellen Plummer prepares F75 with the help of Prince-Marie Louise Childrens Hospital RD Priscilla and University of Ghana interns Sophia and Ohenewaa.

Left to right: Frank (UG), Melissa (McGill), Ellen (ISU), Ohenewaa (UG), Erin (ISU), Kathleen (ISU), Janelle (ISU), Jennifer (ISU), Sophia (UG), Elom (UG), and Collins (UG) pose with their traditional Ghanian wear.

ISU, UG, and McGill Interns stayed at the University of Ghana Nutrition Research and Training Centre in Asesewa, Ghana

ISU Intern Janelle Morimoto and UG Intern Sophia measure recumbent length on a small child.

DI Program Director Jean Anderson (front, center) and ISU DI Faculty Erin Bergquist (left) meet with key partners from UG, Asesewa Hospital, and Plan Canada in early March 2011

ISU Interns Erin Roehl and Jennifer Doumit use an interpreter to interview a Ghanaian mother on complementary feeding practices.

7 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation Grant

Neva Cochran, Ms, RD, LD Nutrition Communications Consultant 6919 Forest Cove Circle Dallas, TX 972-386-9035 nevacoch@aol.com www.nevacochranrd.co

Frederick Green Memorial Internship in Nutrition Communications Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Foundation This award provides a grant for a nutrition and dietetics student who has secured an unpaid, full-time, 6- to 8-week summer internship with an RD who is a member of the Academy specializing in nutrition communications, specically related to media and public relations. The practitioner should be one who can use assistance and provide the student with meaningful experiences related to media and nutrition communications. This must not be a position that the RD could or would normally be able to pay a student or RD to do. Award amount: $2,000 For more information, contact Beth Labrador on the Foundation staff at BLabrador@eatright.org Application may be downloaded at: http://www.eatright.org/Foundation/content.aspx?id=10796 I am also interested in buying a classied ad for a study guide I developed. When is the deadline for the next issue of the newsletter?

Positioning Dietetic Interns and Students for Success in the Job Market

Wendy Phillips, MS. RD, CNSC, CLE Morrison Healthcare/University of Virginia Health System 5700 Locust Ln, Crozet, VA 22932 434-982-2522 wp4b@virginia.edu Janelle Webb, MBA, CLE Kaiser Permanente

Increasing competition for Registered Dietitian jobs in the United States is leading dietetic educators and practitioners to consider how best to prepare their students and interns for the job market. These prospective applicants need to know what potential hiring managers are searching for. Frequently, the job posting is the rst introduction a candidate has to an available position. An effective job posting avoids simply advertising for a clinical dietitian; rather, it is a concise, yet clear description of what the position entails. Often the responsibilities of a dietitian will differ depending on the type of facility, the patient population, and other unique factors. The job posting should also accurately describe, to the extent

8 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

possible, job duties, patient population, schedules, and any other details that might help the applicant understand what to expect. Attention should be paid to job listing placement as well. The more specialized the position, the broader the audience the posting needs to reach since it may be necessary to hire RDs from out of the area to meet the need. Dietetic Practice Groups within the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics are valuable resources when searching for a specialist dietitian. Applicants need to consider how their skills and experiences match the requirements listed, and be ready to offer specic examples of how they qualify for the position. Many companies employ recruiters, so an accurately worded selection criteria that describes who will be included or excluded for consideration as a candidate allows the recruiter, or even an electronic application system, to effectively screen out candidates who do not meet the criteria. This can save time, eliminating the need for the hiring manager to interview candidates who are not fully qualied. The hiring manager needs to carefully consider the selection criteria used for the job to ensure that potential excellent candidates are not excluded. For example, a hiring manager may want to require an advanced degree or specialty certication for a position, but making those job selection criteria could potentially deter excellent applicants or screen out exceptional candidates when these degrees or certications could be obtained soon after hiring. Additionally, a college degree or certicate does not always guarantee a candidate is able to translate the book

learning into clinical skills. Interns and other applicants need to be sure they meet the minimum criteria before applying for the position. Once the qualied applicant list is compiled, the hiring manager then needs to determine which one to hire, requiring him or her to complete many steps in the process. Recruiters will often check references, but the manager responsible for making the nal decision should also check the references of anyone she or he is seriously considering hiring. Applicants will only choose references from those whom they know will say positive things, and this is important for the manager to recognize. However, a skilled manager who has been through the hiring process several times will be able to know if a reference is enthusiastically recommending this applicant for hire. Many companies have a set list of questions they will ask during the reference check, and they may have rules about what can or cannot be asked. If no restrictions are placed on the questions, there are some additional questions a reference may be asked that provide insight into a candidates potential future work performance: 1) Have you seen this applicant perform in a stressful situation? How did he or she handle it? 2) What would the previous coworkers say about his or her ability to function as a member of the team? The interview process is ideally held in person, but whether in person or on the phone, panel interviews are highly

recommended. Although possibly intimidating for the applicant, conducting panel interviews are benecial for existing staff as well as the applicant. It sends the message to the applicant that it is a collaborative work environment where all opinions are valued, allows managers to empower employees of the team with a sense of ownership (1), and it gives the current team members an opportunity to provide feedback into their potential new co-worker with whom they will be working on a daily basis. Including senior management in panel interviews can also provide valuable insights since they have likely conducted many interviews and hired many people, and have had the opportunity to learn from past successes and failures. Ultimately, the direct manager will usually have the nal decision-making capability, since this is the person who will be responsible for the day to day management of the new employee. Through this process the interviewed candidate also gets the opportunity to meet possible future team members and make an initial decision about whether he or she would feel comfortable working with them on a regular basis. The questions asked by the interviewing panel are dependent on the RD job description, the make-up of the interviewing panel, and the specic needs of the current nutrition services team. For example, if the new position is for a pediatric inpatient dietitian, all the pediatric dietitians, both inpatient and outpatient, may be asked to contribute at least in part to the interviewing process, either by submitting interview questions or by sitting on the panel, but

9 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

more candidate selection weight would be given to the other inpatient dietitians with which the RD would have more interaction if hired. Some examples of good interview questions include: 1) Give an example of when you felt overworked. What did you do? 2) Give an example when you noticed another team member feeling stressed and what you did. 3) What do you hope to accomplish in the next 2-3 years as a member of this team? As an extension of the interview, managers, especially Clinical Nutrition Managers, may focus on questions related to quality assurance. An example of a question is Tell me about the Performance Improvement initiatives at your last job and your involvement in those initiatives . The manager will be listening for the applicant to give examples of collaboration, problem solving, and continuous outcome monitoring for improvement of the problem. Answers to interview questions should be carefully considered. The interview process is important in many ways as it can identify potential negatives that will quickly eliminate potential applicants and save the hiring manager time and resources. An example of an interview red ag is an applicant who excessively complains about their previous manager and/or co-workers. While the previous manager and/or co-workers may have been very difcult to work

for, the hiring manager doesnt know if it truly is the actions of the previous manager or if the negativity of this applicant is what caused the disagreements. This doesnt play well with others attitude can be very disconcerting to potential future co-workers. Another interview red ag may be if someone mentions that they were bored at one more of their previous jobs, increasing the likelihood that they will become bored in the position that they are interviewing for. While some positions and locations may be more mundane than others, an exceptional dietitian will look for ways to further their own growth and learning, avoiding boredom and career stagnation. Interview topics of discussion will be predetermined primarily by the hiring manager with input from the interview panel, with care given to ensure that each question that is asked with each interviewed applicant. Important topics for inclusion range from salary (which may depend on education, experience, job experience, or other job duties), vacation accrual, health insurance, and negotiable (if any) job requirements such as work schedules or days worked. While some hiring managers or interview panels may be uncomfortable discussing these subjects, the CNM or hiring manager should not shy away from discussing them. An applicant answers are essential elements to whether or not he or she would be able to accept the position. If the dietitian is unwilling or unable to accept the proffered terms, then the hiring manager does not need to spend the time checking references, hosting a panel interview,

completing a background check, or completing any of the other tasks associated with interviewing. In addition, applicants must be allowed and encouraged to ask questions of their own, without fear of being questioned for their motives of asking said questions. The intern or potential applicant needs to understand all the factors inuencing the hiring decision. A vital hiring metric is past work experience. If the candidate is a newly graduating dietetic intern, he or she will likely have a lot of creative projects to discuss. This is positive, but should be kept in perspective. Internship requirements include activities such as capstone projects and community service, and time is dedicated to such tasks as part of the program. If the RD graduated over one year prior to the interview, then he or she should not be focusing solely on projects done during the internship. Examples need to be given of ongoing professional development above and beyond basic job duties in the time since entering the workforce. Choosing one or two major projects from the internship, such as a major capstone project or a thesis (if a coordinated internship), is always ne, regardless of how far out from graduation the RD is. Likewise, if the internship project or paper is directly related to the job applying for, then it is also ne to discuss during the interview. The concern is when a dietitian has done nothing more than the basic job duties since graduating from the internship. Except for unique cases, this usually means that the dietitian will only strive for more if specically directed to do so. Due to the increased availability

10 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

of eligible dietitians, the market is becoming more competitive. Therefore, potential applicants need to make themselves more marketable and competitive by writing and publishing, conducting research, developing educational materials, providing nutritionrelated community service, or in some other way distinguishing themselves from others. In fact, it has been shown that overall job satisfaction (likely leading to job retention) is linked to greater professional involvement above basic job duties (2,3). Once interviews are completed, the manager will weigh all aspects of the candidates presentation. While the interview itself is very important, all components of the hiring process, such as the aforementioned reference checks and professional portfolios, will be considered during the decision making process. Professional portfolios enable a dietitian to showcase these career and personal achievements, including

activities such as professional writing, charity involvement, and/ or volunteer assignments, as well as previous positions held, that may or may not directly relate to the position the dietitian for which is currently interviewing. Often, hiring managers do not give ample time for the applicant to share their portfolio. Out of professional courtesy and to truly understand what this dietitian is passionate about, time should always be given to review these portfolios. The department can glean best practice ideas from the portfolios, and it may be discovered that the candidate, if hired, can be utilized in more or different capacities than initially imagined. Also, if not selected for the current position, these portfolios can highlight future positions for which the candidate may qualify. Once the appropriate candidate is selected and the offer is accepted, the new team and manager will need to invest adequate time in

training and orienting the new RD. This can be a time of growth for the entire team, with an opportunity to learn through fresh eyes and a new team member with best practice ideas from other facilities and previous experiences. Good managers will draw from this strength and use the opportunity to contribute to their own learning as well. References 1. Edelstein, S. 2008. Managing Food and Nutrition Services: For the Culinary, Hospitality, and Nutrition Professions. Sudbury, MA. 2. Mortensen J, Nyland N, Fullmer S, Eggett D. Professional involvement is associated with increased job satisfaction among dietitians. J Am Diet Assoc 102;10:1452-1454. 3. Sauer K, Canter D, Shanklin C. Describing career satisfaction of registered dietitians with management responsibilities. JAND. 112;8:1129-1133.

Integrating Undergraduate Research into the Curriculum

Amy R. Shows, PhD, RD, LD Professor, Lamar University 409-880-7962 amy.shows@lamar.edu Connie S. Ruiz, PhD, RD, LD, Lamar University Jill Killough, PhD, RD, LD, Lamar University

Undergraduate research is a growing component of university curricula across the United States. It is generally understood that students involved in real-world research at the undergraduate level are stimulated to pursue advanced degrees in areas including science and technology (1). According to Elgren and Hensel (2), students participating in undergraduate research inevitably are exposed

to the primary literature. In addition, research provides students the chance to verbalize and test hypotheses. A nal benet of the research process is that it encourages students to impart objectives, approaches, analyses, and conclusions (2). The didactic curriculum must include research methodology, interpretation of research literature, and integration of research principles into evidence-

11 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

based practice as outlined by The Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND) Foundation Knowledge and Competencies for Entry-Level Dietitians 2008 (3). As one way to involve undergraduate students in research and develop procedures for future undergraduate research projects, we developed an independent study project for three undergraduate students. The independent study curriculum required the student researchers to work individually, as well as collaboratively as a team to complete the project. Instructors worked with student researchers by providing research training, developing the research question/stating the research problem, assigning specic duties, and reviewing completed work. The research problem was to determine the level of knowledge regarding diabetes among African Americans in Southeast Texas. Research Curriculum Goals and Objectives The primary goal of the independent study was for undergraduate students to collaborate on a team project that incorporated all aspects of the research process, including instrument development, data collection, data entry, statistical analysis, and data interpretation. Other learning objectives for the independent study were: Describe the research process as it applies to this community nutrition project. Describe the role of a participant in a community nutrition research project. CONTENT Defense of Thesis/Proposal Attended defense Summary Critique Submitted

Explain the process of writing a thesis for a Masters Degree. Identify different types of scholarly publications.

Although the goals and objectives were the same for all student researchers, the assignments varied to allow for an entire research project to be completed. Prior to Research Prior to starting the project, the undergraduate researchers completed four pre-assignments. The rst pre-assignment required all student researchers to attend either a thesis defense or a thesis proposal defense and then submit a critique of the project presentation. The second pre-assignment required students to complete the online training course offered by the National Institute of Health, Protecting Human Research Participants, and submit the printed certicate of completion (4). The third pre-assignment required each student to participate as a research subject in a specied study. Students were evaluated by the principle investigator and, thus, received feedback regarding their roles as participants in the study. Finally, the student researchers wrote a critique of their experience as a research subject, addressing requirements of study participants and lessons learned about the research process. A checklist (Figure 1) was used to evaluate students participation in the rst three pre-assignments. Also, a standard rubric (Figure 2) was used to assess performance on the fourth pre-assignment (student critique).

Figure 1. Undergraduate Research Project Checklist

CATEGORIES Max points 10 Max points 40 Max points 25 Max points 25

INSTRUCTORS COMMENTS YOUR POINTS

Online Training Submitted certification of completion Submitted within required timeframe

Evaluation Completed by Principal Investigator Max points 20 Student was punctual Max points 20 Student attended all required meetings Max points 60 Student submitted food journals in correct format 200 Points Maximum Score

Your Score

12 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

Figure 2. Undergraduate Research Project Quality Rubric

CONTENT CATEGORY Max Points 50 Description of the study Max Points 25 Identied independent and dependent variables

EXEMPLARY 45-50 points Study was thoroughly described including purpose, methods, sample selection, inclusion and exclusion criteria 25 points Student correctly identied both independent and dependent variables

ACCEPTABLE 35-44 points Study was described somewhat thoroughly with one to two components not addressed 15 points

UNACCEPTABLE <35 points Study was not well described; missing more than two major components

YOUR POINTS

5 points

Student correctly Student did not identied either correctly the independent identify either or dependent the independent variable or dependent variable

Max Points 25 20-25 points 15-19 points <15 points Sentence structure, Paper was well Paper was Paper was punctuation, organized and free somewhat well- disorganized and grammar and of errors in organized and had had more than spelling sentence structure, more than three ve errors punctuation, errors grammer, and spelling 100 Points Maximum Score Your Score

Student Researcher #1 Student researcher #1 completed four nutrition research assignments. In the rst assignment, the student identied a minimum of ve articles pertaining to the research topic with at least four of the articles reporting original research and only one being a review article. Student #1 then compiled a literature review from the aforementioned articles. The articles and literature review were submitted to instructors. Student researcher #1 was also required to develop the instrument that would be used in the study. In addition, the student created the methodology/protocol portion of the study. Finally, the student assisted in developing the draft for study approval by the University Human Subject Review Board.

Student Researcher #2 Student researcher #2 completed four assignments. The rst nutrition assignment required the student to nd a minimum of ve articles pertaining to the research topic with at least four of the articles being original research articles. The student compiled a literature review from the articles. The literature review and articles were submitted to instructors. The student then constructed a draft of the participation request letter to be sent to the administrator of the desired study location. When approval was granted, the student then made arrangements for the location and time for data collection. Third, student researcher #2 met with instructors to discuss the study protocol and receive data collection training. Once trained, the student administered the instrument and collected

13 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

all data from the study sample. Student researcher #2 then submitted all data to the instructors and assisted with data preparation. Student Researcher #3 Student researcher #3 completed four assignments. The student prepared the questionnaires for data entry. With faculty assistance, the student also ran statistical tests and interpreted data. Student researcher #3 organized the study into poster

presentation format. The literature review, purpose of the study, and methodology were taken from student researchers #1 and #2, while student #3 developed the results and discussion. In addition, student researcher #3 developed an abstract of the research (Figure 3) which was submitted to the Texas Dietetic Association (TDA) to be considered for a poster presentation. The research was peer reviewed and selected for presentation; student researcher #1 made the poster presentation at the 2011 TDA Food & Nutrition Conference & Exhibition.

Figure 3. Abstract of Research Submitted by Student #3

ABSTRACT

Background: The prevalence of diabetes remains elevated in African Americans. This study determined level of knowledge regarding diabetes among adult African Americans in Southeast Texas. Also, it identied risk factors for diabetes in this population. Methods: An anonymous self-report questionaire was distributed to a sample of adult members of an African American church congregation. The instrument consisted of 39 items: demographic/ personal items (7), perceived health status (1), dietary practices (10), physical activity (3), medical/ family history (2), and diabetes knowledge (16). Questions included both forced-choice and free response. Results: Thirty-three African American adults particpated in the study, 67% (n=22) were female. Mean age was 44.7+17.64 years.. Seventy-three percent (n=24) of participants were overweight/ obest based on BMI. Almost all (91%, n=30) subjects described their health as good/very good. Although only 24.3% (n=8) had diabetes, 49% (n-16) had a family history of diabetes. Sixty-four percent (n-21) described their diet as unhealthy. Over 50% of subjects consumed less than two servings each of fruits and vegetables, and 61% (n=20) frequently consumed high-fat meats. Fiftyfive percent (n=18) of subjects stated they were familiar with the term diabets, but only 38% (n=12) indicated they knew signs/symptoms of the disease. Circulatory problems and blindness were the two most common complications recognized by subjects. Mean knowledge scoe was 7.4+2.4 (range 1-13). Seventy percent (n=23) of the sample accurately stated they were not involved in enough physical activity. On average, subjects exercised only 2+1.7 days per week. Discussion: Despite the apparent knowledge that diabets shortens life and affewcts quality of life, it appeard this group was not currently involved in efforts to prevent diabets such as adequte exercise and healthy eating. Conclusions: More efforts should be made to motivate the adult AFrican American population to make lifestyle changes that decrease the risk of diabetes.

14 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

Conclusion and Recommendations Designing this independent study curriculum was an attempt to develop a practical research opportunity for undergraduate students. The research curriculum allowed three students to design, implement, and complete an actual research study. Collectively, the students dened the research question, conducted literature reviews, developed methodology and protocol, collected data, performed statistical analysis, examined the results, and created an abstract of the study to be sent to the state dietetic association. Figure 4 illustrates the responsibilities and experiences of each student during the project.

Students met with the primary instructor after project completion. All students found the experience rewarding. One suggestion was to have all students involved in every step of the process as a team rather than individually. All students agreed that a required, formal, original research project would be benecial in an undergraduate class. Although we were only able to include three undergraduate students in this independent study, in the future, we would like to create more research opportunities for our undergraduate students. This approach established a model for incorporating research into the curriculum in the future. The nutrition faculty has identied Community Nutrition as an ideal course for a similar project to be incorporated.

Figure 4. Student Experiences in Research Project

EXPERIENCE

STUDENT 1

STUDENT 2

STUDENT 3

Attend these proposal defense or thesis defense; submit summary critique Complete online Protecting Human Subjects and Research training; submit certificate of completion Participate as a subject in research study; submit summary Submit mini-literature review regarding diabetes mellitus utilizing APA format Develop instrument Develop study protocol Develop draft for study approval by University Human Subject Review Board Obtain permission from administrator at data collection site to conduct stude; arrange location and time for data collection Meet with instructor regarding study protocol and data collection training Collect and submit all data to instructor Prepare instrument for data entry Assist instructor in statistical anaylsis and interpretation Organize study into poster presentation format Submit study abstract to state dietetic association for poster presentation consideration at annual meeting Make presentation at annual meeting X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X

15 | NDEP-Line | Summer/Fall 2012

References (1) Russell S, Hancock M, McCullough J. Benets of undergraduate research experiences. Science 2007;316:548549. (2) Elgren T, Hensel N. Undergraduate research experiences: Synergies between scholarship and teaching. AAC&U peerReview 2006;8:4-7. (3) Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics. Foundation Knowledge and Competencies for Entry-Level Dietitians (2008). Retrieved from the Academy tics website - ACEND homepage: http://www.eatright. org/uploadedFiles/CADE/CADE-General-Content/3-08_RD-FKC_Only.pdf (4) National Institute of Health, Ofce of Extramural Research. Protecting Human Research Participants. Retrieved from: http://phrp.nihtraining.com/users/login.php

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Granting Owps To Rdns Can Decrease Costs Andj Phillips DoleyDokumen8 halamanGranting Owps To Rdns Can Decrease Costs Andj Phillips Doleyapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Fnce 2017 LTC Productivity Benchmarks AbstractDokumen1 halamanFnce 2017 LTC Productivity Benchmarks Abstractapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Nutrition Screening Acute Care Setting Newsletter Winter 2017 Phillips DoleyDokumen8 halamanNutrition Screening Acute Care Setting Newsletter Winter 2017 Phillips Doleyapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Adhd Nutrition Considerations ChecklistDokumen1 halamanAdhd Nutrition Considerations Checklistapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Braden Scale Jan 2017 JandDokumen6 halamanBraden Scale Jan 2017 Jandapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Adhdreferences 2016Dokumen4 halamanAdhdreferences 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Parrish Dec 15 UpdatedDokumen8 halamanParrish Dec 15 UpdatedRhod Bernaldez EstaBelum ada peringkat

- Minimizing False-Positive Nutrition Referrals From The MSTDokumen5 halamanMinimizing False-Positive Nutrition Referrals From The MSTapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- 2201 October p1 DK 13 17Dokumen5 halaman2201 October p1 DK 13 17api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Western Hemisphere ProfileDokumen1 halamanWestern Hemisphere Profileapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Tyler Phillips CVDokumen1 halamanTyler Phillips CVapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Esphlsummaryaug 2014Dokumen1 halamanEsphlsummaryaug 2014api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Beastarsept 2016Dokumen1 halamanBeastarsept 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Pine View Invitational Deca 2nd Place Jan 2016Dokumen1 halamanPine View Invitational Deca 2nd Place Jan 2016api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- PG Malnutritioncoding Sept 14Dokumen7 halamanPG Malnutritioncoding Sept 14api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- PhillipsproductivityarticleDokumen3 halamanPhillipsproductivityarticleapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Phillips NCP June 2015 Malnutrition Coding For NSTDokumen5 halamanPhillips NCP June 2015 Malnutrition Coding For NSTapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Ndep-Line-Winter 2014Dokumen19 halamanNdep-Line-Winter 2014api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Matters Nov14 PhillipsDokumen1 halamanMatters Nov14 Phillipsapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Benchmarkingfeb 2015Dokumen7 halamanBenchmarkingfeb 2015api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Fnce 2014 AbstractmstzechariahphillipsDokumen1 halamanFnce 2014 Abstractmstzechariahphillipsapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Brandnewsletterapril 2014Dokumen9 halamanBrandnewsletterapril 2014api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- 1pageprofile PhillipsDokumen1 halaman1pageprofile Phillipsapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- td10 2015Dokumen6 halamantd10 2015api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Newsletter Fall 2014costbasedaccountingarticleDokumen18 halamanNewsletter Fall 2014costbasedaccountingarticleapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Brandjuly 2014Dokumen6 halamanBrandjuly 2014api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Lobbydaynewsletter 2014Dokumen7 halamanLobbydaynewsletter 2014api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Newsletter Spring 2014 - Icd10Dokumen20 halamanNewsletter Spring 2014 - Icd10api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Katch-Up Mhfs November 12 2012rcnmawardDokumen2 halamanKatch-Up Mhfs November 12 2012rcnmawardapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Dyk October 2012Dokumen2 halamanDyk October 2012api-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Canfield FairDokumen3 halamanCanfield Fairapi-546463844Belum ada peringkat

- PC110R 1 S N 2265000001 Up PDFDokumen330 halamanPC110R 1 S N 2265000001 Up PDFLuis Gustavo Escobar MachadoBelum ada peringkat

- Hotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013Dokumen29 halamanHotel Transportation and Discount Information Chart - February 2013scfp4091Belum ada peringkat

- 14DayReset Meals GeneralDokumen40 halaman14DayReset Meals GeneralRiska100% (1)

- Stress Relieving, Normalising and Annealing: Datasheet For Non-Heat-TreatersDokumen2 halamanStress Relieving, Normalising and Annealing: Datasheet For Non-Heat-TreatersGani PateelBelum ada peringkat

- Subhead-5 Pump Motors & Related WorksDokumen24 halamanSubhead-5 Pump Motors & Related Worksriyad mahmudBelum ada peringkat

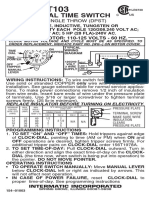

- T103 InstructionsDokumen1 halamanT103 Instructionsjtcool74Belum ada peringkat

- Air Compressors: Instruction, Use and Maintenance ManualDokumen66 halamanAir Compressors: Instruction, Use and Maintenance ManualYebrail Mojica RuizBelum ada peringkat

- Uric Acid Mono SL: Clinical SignificanceDokumen2 halamanUric Acid Mono SL: Clinical SignificancexlkoBelum ada peringkat

- Osma Osmadrain BG Pim Od107 Feb 2017pdfDokumen58 halamanOsma Osmadrain BG Pim Od107 Feb 2017pdfDeepakkumarBelum ada peringkat

- Air MassesDokumen22 halamanAir MassesPrince MpofuBelum ada peringkat

- UntitledDokumen18 halamanUntitledSpace HRBelum ada peringkat

- Eye Essentials Cataract Assessment Classification and ManagementDokumen245 halamanEye Essentials Cataract Assessment Classification and ManagementKyros1972Belum ada peringkat

- DM - BienAir - CHIROPRO 980 - EngDokumen8 halamanDM - BienAir - CHIROPRO 980 - Engfomed_twBelum ada peringkat

- Ppr.1 Circ.5 Gesamp Ehs ListDokumen93 halamanPpr.1 Circ.5 Gesamp Ehs ListTRANBelum ada peringkat

- SpectraSensors TDL Analyzers in RefineriesDokumen8 halamanSpectraSensors TDL Analyzers in Refineries1977specopsBelum ada peringkat

- Factors Associated With Early Pregnancies Among Adolescent Girls Attending Selected Health Facilities in Bushenyi District, UgandaDokumen12 halamanFactors Associated With Early Pregnancies Among Adolescent Girls Attending Selected Health Facilities in Bushenyi District, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONBelum ada peringkat

- Entrepreneurship Paper 2Dokumen3 halamanEntrepreneurship Paper 2kisebe yusufBelum ada peringkat

- Sialoree BotoxDokumen5 halamanSialoree BotoxJocul DivinBelum ada peringkat

- Biology Lab ReportDokumen5 halamanBiology Lab Reportapi-2576094460% (1)

- Summative Test SolutionsDokumen1 halamanSummative Test SolutionsMarian Anion-GauranoBelum ada peringkat

- Fire BehaviourDokumen4 halamanFire BehaviourFirezky CuBelum ada peringkat

- Melancholic PersonalityDokumen5 halamanMelancholic PersonalityChris100% (1)

- Red Winemaking in Cool Climates: Belinda Kemp Karine PedneaultDokumen10 halamanRed Winemaking in Cool Climates: Belinda Kemp Karine Pedneaultgjm126Belum ada peringkat

- Polyken 4000 PrimerlessDokumen2 halamanPolyken 4000 PrimerlessKyaw Kyaw AungBelum ada peringkat

- Biography of Murray (1893-1988) : PersonologyDokumen6 halamanBiography of Murray (1893-1988) : PersonologyMing100% (1)

- Bleeding in A NeonateDokumen36 halamanBleeding in A NeonateDrBibek AgarwalBelum ada peringkat

- Building Technology (CE1303) : Window: Lecturer: Madam FatinDokumen19 halamanBuilding Technology (CE1303) : Window: Lecturer: Madam FatinRazif AjibBelum ada peringkat

- Anatomy, Physiology & Health EducationDokumen2 halamanAnatomy, Physiology & Health Educationsantosh vaishnaviBelum ada peringkat

- ListwarehouseDokumen1 halamanListwarehouseKautilya KalyanBelum ada peringkat