How To Consult The Yijing

Diunggah oleh

adisebeJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

How To Consult The Yijing

Diunggah oleh

adisebeHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1

How to consult the Yijing

The Yijing is a book you come to understand not so much through reading it cover to cover but through asking it questions about your own life and concerns. It does take quite a while to become familiar with the Book of Changes, but to start you form a question, such as 'How would it work out if I did such-and-such?'. Other examples: 'Consequences of taking this new job I've been offered?', 'I'm thinking of moving house, is this a good idea at this time?' Don't use questions with a 'fork' in them, 'Should I do A or B?', since this makes it difficult to interpret the answer. Instead, consult the Yijing twice, once for each choice. Ask 'Oracle for going ahead with A' and then 'Oracle for going ahead with B', and compare the results. You could ask two questions over any matter, since it usually boils down to a choice between doing it and not doing it. Ask for an oracle for going ahead and then an oracle for not going ahead, this will usually make the best path clear. This in fact was the way the Shang divined as a standard practice. 'Oracle for' and 'Consequences of' are just two ways I evolved over the years to formulate questions, you can phrase the question in whatever way feels right to you. You may not get to the heart of what you want to know straight away and the oracle you receive from the Yijing may clarify that for you, leading to a more precise and honed question. You don't have to ask a question, you can simply consult the book and see what it says in the hope that it is relevant to something in your life, but in general this doesn't work as well. The clearer the question, the clearer the answer. If you ask a vague question the likelihood is that the answer will be vague or that you won't really understand it. So first you get your question. It's a good idea to write it down on the piece of paper that you will form the hexagram on. Then you might light a stick of incense, take three coins of the same denomination, such as 2p, pass them through the incense clockwise three times (just a little ritual to begin), then you shake the three coins in your hands and drop them to the ground while mentally asking your question. This is something you do 6 times, each time you form a line of a hexagram, starting at the bottom and working upwards. When you drop three coins there are 4 possible combinations you can get. Assign heads as 3 and tails as 2 and you get: 3+3+3=9 a moving yang line, also called old yang

3+3+2=8 a yin line, also called young yin 3+2+2=7 a yang line, also called young yang 2+2+2=6 a moving yin line, also called old yin

Old yin and old yang are about to change into their opposites (enantiodromia, the principle that things change when they reach their extremity). Old yin changes to young yang, old yang to young yin. Some people wonder whether heads is yang or tails. In my view it is arbitrary and it doesn't matter which you choose, I have simply chosen heads to be 3 and tails to be 2, and although yang is always 3 and yin always 2 I am not saying I regard heads necessarily as yang, and if you use Chinese coins it is irrelevant anyway. If a coin lands on its edge, propped against a chair leg for instance, take the side you can immediately see. If you drop a coin before you are ready, follow your natural spontaneity to know what to do, either let the other coins fall with it, or pick it up and place it back in your hand. When I am teaching Yijing, if a student is using the coins in my presence, and a coin 'accidentally' drops, I usually say leave it as it falls, follow it with the others; but if the student naturally reaches to pick the coin up, tightening their grasp on the others, I say go ahead, pick it up, that was your instinct on this occasion.

*

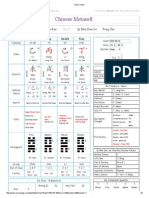

An unchanging young yang line (7) is solid:

An unchanging young yin (8) is broken:

A moving old yang line (9) has a circle in the middle to indicate it is a solid line about to change into a broken line:

A moving old yin line (6) has a cross in the gap to show it is about to form a solid yang line (think of it as two arrow-heads pointing at each other, coming together to join if you like):

Okay, so you have these four types of line. Now you drop the 3 coins to the ground, and form one of these lines. Then drop the coins again and form another line on top of it, etc, until you build up a hexagram of six lines from the bottom to the top. You might get this, for instance:

The totals for these lines were as follows:

7 7 8 6 8 7

This is hexagram 42, more specifically 'hexagram 42 changing in the third place'. To find out which hexagram you have received you go to the back of Wilhelm to the chart and you can look it up via the top three lines and the bottom three lines (the upper trigram and the lower trigram). You read for your answer all of the text up to where the commentary on the lines starts, i.e. the Judgment and the Image. But in the lines you only read the 'Six in the third place'. It's 'six' because it's a moving yin line. The main answer to your question is always in the lines that change. You read them because they're changing, the changing line represents a dynamic change in the world that you can connect to via the catalyst of the text. In this example only one line changes, but all 6 can change, which gets more complex (see below). Now, because the third line is an old yin line changing into a young yang line, a second hexagram is formed, hexagram 37, which as you see below has a solid line in the third place, the rest of the lines remaining the same. So for this consultation you would read

hexagram 42 up to the lines, then just the third line, which you would regard as the answer to the question. You would read hexagram 37 as the future situation resulting from the change in the third place:

(This oracle indicates something beneficial and unforeseen coming about as a result of what at first appears to be an unfortunate situation.)

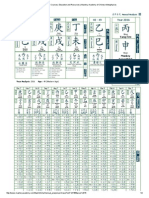

Chinese coins

You can use any coins, but later you may wish to buy three old Chinese coins from a coin shop. These have a square hole in the centre, the circle of the coin represents heaven and the square in the middle is earth. It's best to buy these from a coin shop and avoid what look like Chinese coins (sometimes strung together with red cord) in New Age shops and Chinese shops in Chinatown that sell fengshui lucky three-legged toads and suchlike. These 'coins' have never been in anyone's pocket, they are fake and will snap in half quite easily if you try to bend them. Most coin shops have a box of cheap old Chinese coins, pick ones that aren't too worn but it doesn't matter that they're grubby since they clean up well after soaking in vinegar or, better, clean them up with Brasso. Then boil them for a little while in salt water as part of a ritual to make them your own. People may say this is to get rid of other people's energies and other such superstitious explanations, but you can believe what you like. Essentially it is a ritual to make a line between what they were and what they are now, coins for consulting the Yijing with. The coins will probably have 4 characters on one side and 2 on the other. Give one side a value of 2, the other 3, and stick to it. Later you will not even add up the sides, you'll just look and write down a line, but at first write down the numbers as well, to avoid error while you're getting used to it.

Consulting the Yijing by tossing three coins is called Wenwang ke: 'to enquire of King Wen' or 'King Wen's divination'. I have these three characters brushed on a slip of paper which I keep with the coins in a grey slate Chinese ink bowl with lid. The bowl is a square block of slate with a circular ink reservoir. I used to use it to grind Chinese stick ink into when practising calligraphy, but now I just use it for Yijing coins. The coin method is also known as the 'Forest of Fire Pearls Method' (huozhulin fa).

Does it matter what direction you face?

With the Western interest in fengshui has come an awareness that directions are important in Chinese thought. Personally, I don't think it matters what direction you face, but if you think it is important then you should face north in my considered opinion. In China the Emperor faced south. The Yijing itself has been likened to the Emperor (much as the fourth line of some hexagrams represents the minister and the fifth line the prince) so you could place the book in front of you and face the Emperor.

How to interpret changing lines

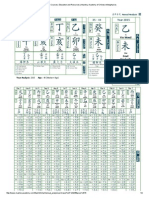

Changing lines are the most important aspect of an interpretation, because these are the points of change into the second hexagram. (When no lines change it usually indicates that the situation will stay the same for a while.) Sometimes the lines contradict what the judgment says, and if you attempt to interpret without realising just how important the lines are for providing the ultimate flavour to the interpretation then you may well misinterpret. I use my own adaptation of Zhu Xi's rules, which he published in 1186 in the fourth chapter of his 'Introduction to the study of the Changes', or Yixue qi meng. See Joseph Adler's translation of this text. My method is the same as that described by Zhu Xi, except for when three lines change: 1 line changes

this is your answer, take it to be the answer in preference to a contradictory judgment (the lines always take precedence over the judgment if there is contradiction)

2 lines change

uppermost line of the two is most important

3 change

middle most important (for Zhu Xi's original method for three changing lines, see below)

4 change

go over to the second hexagram and take the lowermost of the two lines that have not changed from the first hexagram (example below)

5 change

in the second hexagram take the line that hasn't come from a change in the first hexagram (example below)

6 change

the first hexagram's situation is entirely past or on the brink of change, the second hexagram is more important, take the judgment (hexagrams 1 and 2 have an extra line statement that is intended to be read when all six lines change)

Read all the lines that change, going upwards in the hexagram, but lay the emphasis as above, even though when four and five lines change you are emphasising a line in the second hexagram. When that many lines change the emphasis has clearly shifted to the second hexagram. When I say read all the lines that change, that's because it will give familiarity with the content of the book in actual situations and because it is a good habit in the beginning. But after you have been consulting the oracle for many years you'll probably just read where the emphasis is. (When you've used the Book of Changes a long time, you'll have it all virtually memorised and will have a good overview of all the hexagrams and will go to the emphasised text essentially to remind yourself, or you may even be so familiar with the text that you have no need to take the book off the shelf, the words already in your mind just looking at the hexagram and changing lines that you have drawn on the paper.)

If no lines change you can read the governing ruling line, if there are two then take the uppermost. But if the judgment and the ruling line contradict each other, consider asking a rephrased question, unless you have an intuitive sense of the meaning. Bear in mind when reading the governing ruler of an unchanging hexagram that this is only a likely potential for change, it is not actually a changing line. To leave an unmoving hexagram it has to be done through the lines, so the governor could be used to focus your attention on where change may be created. These rules remove contradictory messages by guiding you to a single prognostication out of the variations on the theme. For example, in hexagram 60 in the first line not going out the door to the courtyard is without error, but in the second line not going out the gate of the courtyard is disastrous. A matter of timing. If you had those two lines changing then applying the above rules would tell you to lay emphasis on the second line. Change moves upwards in a hexagram, that's why the uppermost of a two-line change is more important. In the example quoted, the first line shows where you are, you have not yet left the courtyard and that has been fine, but now the second line has been reached, and it is time to leave, carrying on as before will not serve you though it has been fine up until now. A good example of a contradictory and ambiguous hexagram is 54. The judgment is negative, but the fifth line is extremely positive. If you received hexagram 54 with the fifth line changing you would disregard the ominous judgment. To ensure that the four- and five-line changes are clear, an example of each. If you receive hexagram 1 changing in the first four places, you would look at the fifth line of hexagram 20 and regard that as the answer to your question. If you receive hexagram 1 with all but the third line changing, you would look at the third line of hexagram 15. These rules are to an extent arbitrary, but I have found them to work well in practice.

Zhu Xis three-line change

Zhu Xi doesn't use the line statements at all for three lines changing but rather the judgment of both hexagrams. He then provides a set of 32 charts that you need to consult to decide whether to emphasise the judgment of the first or the second hexagram.

I have never liked this method. First, because it requires the use of extraneous materials in the form of these 32 charts. Second, because I do not think it is justifiable to ignore what the lines say when three change, which surely reflect the dynamic of the change better than a kind of balancing act between the two hexagram judgments. That said, if you wish to apply Zhu Xi's original rule for a three-line change but do not have the charts handy (they are included in Adler's book), then you may be interested to know that Ed Hacker discovered a much simpler rule that has the same effect as Zhu Xi's 32 charts but does not require them. Namely, when three lines change, if the bottom line of the hexagram is among those changing then the first hexagram's judgment should take precedence over the second. If not, you stress the second hexagram's judgment over the first. There is no rationale for this beyond the fact that it just happens to give the same result as Zhu Xi's charts.

Hexagrams and changing lines

The Primary Hexagram

The primary hexagram is the hexagram you cast. This is the key to your answer - it's like the stage and scenery of the play, the setting that defines what can unfold here. Start reading here... Did you receive any changing lines? (That is, any with the value 6 or 9?) In about five in every six readings, you can expect to have at least one line changing. But if you haven't, here's information on unchanging hexagrams.

If you received a hexagram with changing lines

Changing (or 'moving') lines in a reading add new possibilities and depth. Once you've drawn and identified your primary hexagram, you need to let them change! Every old yin (6) becomes young yang (7) Every old yang (9) becomes young yin (8) The other lines - the 7s and 8s - stay the same. When every changing line has transformed into its opposite, the result is your relating hexagram So for example, the primary hexagram 36, Brightness Hiding, with its second line changing...

...would give the relating hexagram 11, Harmony:

10

The Relating Hexagram

There are many ways in which the relating and primary hexagrams can work together: the I Ching is endlessly flexible and inventive in expressing new meanings. The advanced I Ching Course devotes a full lesson to exploring the interactions of primary and relating hexagrams and helps you to work out the inner dynamics of your own readings in practice. Exactly what the relating hexagram means for you depends on the kind of question you asked, as well as on how the particular hexagrams involved relate to one another. It tends to be more subjective, working as a direction or 'pull' on the situation of the primary hexagram. It could be the potential outcome, or the way you relate to the situation. The main texts for this hexagram will all be relevant to your question, but none of the line texts is.

The idea behind changing lines... ...is that yang and yin are constantly cycling: each is always changing into the other. The unchanging lines are known as 'young yin' and 'young yang' they are still stable. 'Old yang' is at a later stage in the cycle, and is in the process of changing into yin. 'Old yin' is in the process of changing into yang. This ceaseless change is captured in the tai chi symbol:

The changing lines

Turning back to your primary hexagram: you need to read the texts associated with each moving line. When you receive one or more changing lines in your answer, they highlight moments of change, present or future, and reveal exactly where you are within the broader picture painted by the primary hexagram. They may point to important choices, opportunities or dangers, and provide very useful advice on the best way to deal with them. This part of the reading is the most specific to your present situation. It is traditional to read the bottom line as referring to the present or near future, and the higher lines as referring to a more distant future. But the different lines can also refer to alternative approaches to the basic situation that the primary hexagram describes, or

11

even to different people. The I Ching Course explains and illustrates many ways in which apparently contradictory changing lines can work together. There's also more information in this article on multiple moving lines.

If you received an unchanging hexagram

If none of the lines in your primary hexagram are changing (ie if they're all 7s or 8s) then all your answer is contained within its texts - every text, that is, apart from the moving lines. You may read books that call this a 'locked' hexagram and consider it a bad sign, an indication of stagnation. Don't worry that kind of prejudice comes from a fairly common misunderstanding, when people imagine that the hexagrams are static in themselves. They're not! As with any other answer from the I Ching, how 'good' or 'bad' an unchanging hexagram is depends on the unique combination of the hexagram, your situation, and your desires. With a single hexagram reading, the I Ching is giving you a straightforward and emphatic answer, inviting you to take the time to understand this hexagram to the full. (It may be something you need to understand before you can move on.) You may want to explore the constellation of connected hexagrams that surround it and help to define its meaning the hexagrams of context. Now you have your complete reading, you can start on I Ching interpretation

12

An I Ching reading: How to approach answers with multiple moving lines?

It seemed a good idea to ask the I Ching for advice on this - and not to use the one-lineonly method! Answer: Hexagram 58, Communicating Joy, changing to Hexagram 8, Seeking Union. (Note: this article will be a lot easier to read if you have your own I Ching open alongside you!) The I Ching has very obligingly given us a reading here with three moving lines, so we can use it to try out different methods, and see which makes most sense. First, a lightning tour of the answer as I would normally read it: Communicating Joy The oracle's answers are a joyous communication, and the first thing is to respond with joy. (And not with 'argh, how am I meant to make sense of this?'!) Be responsive, use both inner dialogue and conversation with friends, and persist. Interact with the reading, question it and listen to it. Don't sit obstinately alone with it (Hexagram 52, the opposite); don't expect it to be hidden when all is in the open (contrasting hexagram 57). Take joy in the reading and you will forget that multiple moving lines are supposed to be hard work! Chinuajin's many excellent readings in the Friends' Area show a sensible approach to multiple lines: look especially at the primary hexagram's nuclear hexagram. In this case that is #37, People in the Home, which might lead to emphasis on order and stability, finding each line its place in a secure structure. Seeking Union This is a picture of the individual querent (person asking the question): looking for something they can unite with, something that will give them a clear lead. Also this shows a good way to respond: returning to the source of the oracle consultation, in other words looking again at yourself and your question. This hexagram can also mean that asking again is acceptable, perhaps once you have clarified your question. However, it's vital not to 'sit on the fence' for too long, but to make a choice and act on it. The unifying message here is that the responsibility for finding the right answer is your own. If you attain the full potential of Seeking Union, you can respond with delight, joining with whatever naturally attracts you. The three moving lines

13

Line 1: 'Harmonious communication. Good fortune.' There is inner harmony at this first meeting with the oracle: this is an unbiased, spontaneous response. Here is the ideal querent: someone without bias or attachment to any particular answer, independent of mind and naturally at one with the I Ching. Line 2: 'Sincere, confident communication. Good fortune. Regrets vanish.' The ideal querent is still at work! S/he has approached the oracle with perfect sincerity, and accepts its answer with complete trust. S/he is centred and at one with the moment, and enjoys open communication with the spirit. Line 4: 'Bargaining communication, not yet at peace. Limiting affliction, there is rejoicing.' 'Bargaining' is what merchants do: they calculate, haggle and barter. Anyone who has tried to weigh up the input of several apparently contradictory lines will recognise this description. 'Not yet at peace' echoes Hexagram 8 - 'not at peace, coming from all sides': the image of the querent's many concerns which seek a single, clear lead from the reading. With multiple moving lines, such a lead is not immediately forthcoming! 'Limiting' also means finding protection against something; 'affliction' also means pressure and haste. To overcome this unproductive tendency to haggle with the oracle and get the 'reward' of a positive understanding, you need to set limits to your own anxiety. Lines 1 and 2 obviously work well together. Be open, spontaneous, sincere and trusting, and the answer is given to you. But line 4 shows a quite different (and, if I'm honest, rather more familiar) scenario. What should we be doing - trusting, or haggling and limiting?

Three sources of information for understanding all the lines together

Line position and sequence Understanding that the lines come in a specific order is tremendously helpful. The sequence of the lines in a hexagram is from bottom (line 1) to top (line 6), and so the events they describe, or advice they offer, can also be read in that sequence. If you combine this with an understanding of the basic role of each line position, even apparently contradictory advice can make a lot of sense. Naturally, once you have reached line 4, the moment of putting ideas into practice, the advice will have changed from that at line 1, when you were just beginning to form the ideas.

14

In this reading, line 1 is at the beginning, an initial and personal response. It's yang in a yang position, by nature strong and secure. Line 2 is very close to this, but also inwardly centred, and entering into communication with the oracle. Line 4 has crossed over into the upper trigram, where decisions have to be made and things have to be put into practice. It's yang at a yin position, less secure and with more demands on it, and has to decide what to follow. Someone in this position needs to create limits and rules in addition to simple trust. The steps of change Formed by changing each moving line in isolation, the steps of change are like miniature relating hexagrams for each line. They show the context for the change in the line, and also the kind of response that draws forth the line's advice. So in this case: Line 1 points to 47, Oppression: someone self-contained to the point of isolation, learning independence. Line 2 points to 17, Following: someone who is in the moment, naturally following the signs. Line 4 points to 60, Limitation: finding the right limits to set on the conversation with the oracle without stifling it; seeking out a common language. This sounds to me like the methods of limiting the moving lines. The patterns of change These are formed by replacing each changing line with a yang, each stable with a yin to find the outer pattern; the inner pattern is the opposite of this. The inner pattern of change is Hexagram 53: we experience the reading as a gradual, step by step movement towards union and fulfilment, one that can't be hurried. But as an outward experience, and when we look to the reading for advice on how to act in the outer world, things change in the pattern of Hexagram 54. We're plunged into something we can't control or direct. Multiple lines will not be shaped to fit our preconceptions or our particular needs, however urgent. The Image section (Ta Hsiang) in both these hexagrams could also be relevant! So in conclusion, I would read these lines as alternatives - different people (or the same person at different times) needing to take a different approach. If you find yourself haggling, and can't reach a decision on the basis of the first two lines, you need to look for ways to limit your anxiety.

15

Three methods to limit the number of moving lines

Master Yin's rules Alfred Huang, in his Complete I Ching, has a set of rules for reducing multiple moving lines to just one:

2 moving lines, one yin, one yang: consult the yin one. 2 moving lines of the same kind: consult the lower one. 3 moving lines: consult the middle one 4 moving lines: consult the upper of the two unmoving lines 5 moving lines: consult the one unmoving line 6 moving lines: just consult the Judgement of the relating hexagram (except in hexagrams 1 and 2, when there is a special text for all six lines moving)

That reduces this reading to just line 2 - arguably the essence of the reading, but it seems a shame to miss the recognition and insight of line 4. Chu Hsi's rules At the discussion page on this subject at the I Ching Community, you'll find a reposting of Chu Hsi's rules (originally from Felix). These rules are similar to Huang's - they give the same result for this reading - but not identical:

1 line changes: read that line 2 lines change: uppermost is most important 3 change: middle most important, with uppermost possibly confirming (but if they are contradictory stick with the middle one) 4 change: go over to the second hexagram and take the lowermost of the two lines that have not changed from the first hexagram 5 change: in the second hexagram take the line that hasn't come from a change in the first hexagram 6 change: then the first hexagram's situation is entirely past or on the brink of change, the second hexagram is more important. Take the judgement If no lines change you can read the ruling line, if there are two ruling lines then take the uppermost.

The Nanjing rules The earliest recorded I Ching divinations are in the Zuo Commentary, and they never consult more than one line. Sometimes they choose a line text to consult, sometimes a Judgement. In the 1920s, a group of scholars reconstructed a method that would account for the ancient diviners' choices. Here is its application to this reading:

16

1. Add all 6 line numbers (moving yang=9; stable yin=8; stable yang=7; moving yin=6): 9+9+8+9+7+8=50 2. Subtract the result from 55: 3. 55-50=5 4. Use this remainder to count up to the relevant line - line 5. 5. This line being unchanging, when there are exactly 3 changing lines, the hexagram statements from both first and second hexagrams form the oracle, and the line texts aren't referred to at all. (I don't have space here for a complete account of this rather elaborate method. You can find a detailed explanation of all the rules of this method and their rationale, along with translations of all the divinations from which they were deduced, in Richard Rutt's Zhouyi.

A whole new perspective

Gary Bastoky wrote to me about a method he learned from a friend: 'My question is, do you have a recommended method of consulting multiple changing lines? My friend has a very different approach than any I've ever read about, and it seems to make sense -- more sense than even Huang's suggestions. He creates a new hexagram for each changing line, and only the lowest line that is changing in that particular sequence is consulted, in EACH new hexagram -- basically a progression of time and thus events.' He gives this example: 45 with changing lines in the first, fifth, and sixth place. Change Hexagram 45, line 1: get hexagram 17. Read Hexagram 17, line 5, and change it: get Hexagram 51. Read Hexagram 51, line 6, and change it: get Hexagram 21. Gary again: "What this means is that the first line in #45 is the first in a series of events or processes that may or may not be a catalyst which causes the event or process that occur in line 5 of #17, and so on. In this example, line 5 in #17 is the only ruling line in the group and is therefore the most important or the biggest catalyst that finally results in #21 (Biting Through).' For our reading on moving lines, Gary's method works like this:

17

58, change line 1, giving 47, change line 2, giving 45, change line 4, giving Hexagram 8 The second and fourth lines of Hexagram 58 don't feature at all. In this case you begin with harmony and spontaneity (58,1)... ...but find yourself stymied and oppressed amid plenty (47,2). Opportunity is on the way, though, and you encourage this by making offerings, showing sincerity and trust, rather than setting out to introduce an order of your own creation. ...Perhaps as a result of accomplishing this, you attain 'great good fortune' (45,4) ...and can achieve the naturally right choice of Hexagram 8. (Or else, if you are unsure, you consult again!) The idea behind this method is quite different from my usual reading. The lines are definitely expected to represent a process, rather than, say, mutual relationships or alternative positions to take within the landscape of the primary hexagram. If the subject of your enquiry can be considered as a step-by-step process, this seems to be a method to experiment with! I won't be changing over to this method any time soon, but I have to admit that in this case it has produced a narrative that makes a lot of sense.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Words of Radiance: Book Two of The Stormlight Archive - Brandon SandersonDokumen6 halamanWords of Radiance: Book Two of The Stormlight Archive - Brandon Sandersonxyrytepa0% (3)

- Ba Zi Chart1Dokumen2 halamanBa Zi Chart1adisebe100% (1)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Chapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFDokumen7 halamanChapter 10 Tute Solutions PDFAi Tien TranBelum ada peringkat

- Feng Shui Courses, Education and Resources - Mastery Academy of Chinese MetaphysicsDokumen2 halamanFeng Shui Courses, Education and Resources - Mastery Academy of Chinese MetaphysicsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Daci Ciolo: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanDaci Ciolo: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Ba Zi ChartDokumen2 halamanBa Zi ChartadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Rain Day MasterDokumen29 halamanRain Day Masteradisebe100% (6)

- Barbat Nusa: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanBarbat Nusa: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- XXX XXXXXXXXXX: 40 49 Year 2015Dokumen2 halamanXXX XXXXXXXXXX: 40 49 Year 2015adisebeBelum ada peringkat

- XXX XXXXXXXXXX: 40 49 Year 2016Dokumen2 halamanXXX XXXXXXXXXX: 40 49 Year 2016adisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Warren Buffet: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanWarren Buffet: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Heluo Inserting Distance Learning Private Training For GroupDokumen8 halamanHeluo Inserting Distance Learning Private Training For Groupadisebe0% (1)

- Mihnea Calciu: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanMihnea Calciu: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Qi Men FREE ProductDokumen1 halamanQi Men FREE ProductadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Cristina Catalin Carmen: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanCristina Catalin Carmen: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Irina Chitoiu: 30 39 Year 2015Dokumen2 halamanIrina Chitoiu: 30 39 Year 2015adisebeBelum ada peringkat

- XXX XXXXXXXXXX: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanXXX XXXXXXXXXX: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- George Vlantoiu: 35 44 Year 2015Dokumen2 halamanGeorge Vlantoiu: 35 44 Year 2015adisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Felix Lupu: 47 56 Year 2015Dokumen2 halamanFelix Lupu: 47 56 Year 2015adisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Emil Emil: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanEmil Emil: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Camelia Camelia: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanCamelia Camelia: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Art of Chinese AstrologyDokumen11 halamanArt of Chinese Astrologyadisebe100% (1)

- StarsDokumen9 halamanStarsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Heluo Inserting Distance Learning Private Training For GroupDokumen8 halamanHeluo Inserting Distance Learning Private Training For Groupadisebe0% (1)

- Yi CardsDokumen20 halamanYi CardsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- The 12 Growth and Phases AttributesDokumen5 halamanThe 12 Growth and Phases Attributesadisebe80% (5)

- Gigel Maria: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanGigel Maria: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Eminem Eminem: Personal ParticularsDokumen2 halamanEminem Eminem: Personal ParticularsadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- Formula Stele Xuan Kong OrareDokumen4 halamanFormula Stele Xuan Kong OrareadisebeBelum ada peringkat

- State Space ModelsDokumen19 halamanState Space Modelswat2013rahulBelum ada peringkat

- Manuel SYL233 700 EDokumen2 halamanManuel SYL233 700 ESiddiqui SarfarazBelum ada peringkat

- Lodge at The Ancient City Information Kit / Great ZimbabweDokumen37 halamanLodge at The Ancient City Information Kit / Great ZimbabwecitysolutionsBelum ada peringkat

- The Palestinian Centipede Illustrated ExcerptsDokumen58 halamanThe Palestinian Centipede Illustrated ExcerptsWael HaidarBelum ada peringkat

- AE Notification 2015 NPDCLDokumen24 halamanAE Notification 2015 NPDCLSuresh DoosaBelum ada peringkat

- Math F112Dokumen3 halamanMath F112ritik12041998Belum ada peringkat

- Maya Deren PaperDokumen9 halamanMaya Deren PaperquietinstrumentalsBelum ada peringkat

- Module 5 What Is Matter PDFDokumen28 halamanModule 5 What Is Matter PDFFLORA MAY VILLANUEVABelum ada peringkat

- Trina 440W Vertex-S+ DatasheetDokumen2 halamanTrina 440W Vertex-S+ DatasheetBrad MannBelum ada peringkat

- Breastfeeding W Success ManualDokumen40 halamanBreastfeeding W Success ManualNova GaveBelum ada peringkat

- Gis Data Creation in Bih: Digital Topographic Maps For Bosnia and HerzegovinaDokumen9 halamanGis Data Creation in Bih: Digital Topographic Maps For Bosnia and HerzegovinaGrantBelum ada peringkat

- AISOY1 KiK User ManualDokumen28 halamanAISOY1 KiK User ManualLums TalyerBelum ada peringkat

- Alfa Week 1Dokumen13 halamanAlfa Week 1Cikgu kannaBelum ada peringkat

- ReadingDokumen205 halamanReadingHiền ThuBelum ada peringkat

- 0012 Mergers and Acquisitions Current Scenario andDokumen20 halaman0012 Mergers and Acquisitions Current Scenario andJuke LastBelum ada peringkat

- Soft Skills & Personality DevelopmentDokumen62 halamanSoft Skills & Personality DevelopmentSajid PashaBelum ada peringkat

- Origin ManualDokumen186 halamanOrigin ManualmariaBelum ada peringkat

- Case Study - Suprema CarsDokumen5 halamanCase Study - Suprema CarsALFONSO PATRICIO GUERRA CARVAJALBelum ada peringkat

- BBL PR Centralizer Rig Crew Handout (R1.1 2-20-19)Dokumen2 halamanBBL PR Centralizer Rig Crew Handout (R1.1 2-20-19)NinaBelum ada peringkat

- Full Project LibraryDokumen77 halamanFull Project LibraryChala Geta0% (1)

- Simon Ardhi Yudanto UpdateDokumen3 halamanSimon Ardhi Yudanto UpdateojksunarmanBelum ada peringkat

- European Asphalt Standards DatasheetDokumen1 halamanEuropean Asphalt Standards DatasheetmandraktreceBelum ada peringkat

- Contemporary Strategic ManagementDokumen2 halamanContemporary Strategic ManagementZee Dee100% (1)

- SDSSSSDDokumen1 halamanSDSSSSDmirfanjpcgmailcomBelum ada peringkat

- Mcdaniel Tanilla Civilian Resume Complete v1Dokumen3 halamanMcdaniel Tanilla Civilian Resume Complete v1api-246751844Belum ada peringkat

- SIVACON 8PS - Planning With SIVACON 8PS Planning Manual, 11/2016, A5E01541101-04Dokumen1 halamanSIVACON 8PS - Planning With SIVACON 8PS Planning Manual, 11/2016, A5E01541101-04marcospmmBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of Rates (Nh-15 Barmer - Sanchor)Dokumen118 halamanAnalysis of Rates (Nh-15 Barmer - Sanchor)rahulchauhan7869Belum ada peringkat

- Img 20201010 0005Dokumen1 halamanImg 20201010 0005Tarek SalehBelum ada peringkat