12 de Agosto (Schmalensse)

Diunggah oleh

Paul Rosado OlivosDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

12 de Agosto (Schmalensse)

Diunggah oleh

Paul Rosado OlivosHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

American Economic Association

Antitrust and the New Industrial Economics Author(s): Richard Schmalensee Reviewed work(s): Source: The American Economic Review, Vol. 72, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the NinetyFourth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1982), pp. 24-28 Published by: American Economic Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1802297 . Accessed: 01/02/2013 20:36

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Economic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Antitrustand the New IndustrialEconomics

By RICHARD SCHMALENSEE*

My assignment here is to assess the implications of recent theoretical work in industrial economics for antitrust in the United States. I don't have space enough to present a comprehensive survey of that work, nor even to catalog all recent developments with apparent antitrust implications. I attempt instead to describe the general character of those implications, limiting myself to a few illustrative specifics. Industrial economics affects antitrust policy in three different ways. First, it is used in positive analysis aimed at determining whether or not current law has been violated in specific cases and at assessing damages due injured parties. Second, it should be used in evaluating the desirability of relief that might be imposed in particular cases in order to alter structure or conduct if a violation is found. Finally, the tools and results of industrial economics are important inputs in the formulation of general rules of law. I argue here that the new industrial economics can contribute a lot to the positive analysis of individual cases, but it has much less to say about the desirability of particular relief or of general rules of law. A final section briefly examines some implications of this situation. of Particular Cases I. PositiveAnalysis The central problem facing an economist concerned with a particular antitrust case is model selection. In order to select an explicit or implicit model of the situation under study, the economist usually must consider such issues as the sources and magnitude of market power and the economic implications of controversial business practices. Available (inevitably incomplete) evidence must be used

*Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I am indebted to the Ford Motor Company for financial support and to R. Caves, F. M. Fisher, J. E. Harris, P. L. Joskow, P. Steiner, and I. M. Stelzer for helpful comments. 24

to choose among alternative models. Once a model has been selected for a particular case, noneconomists-a judge or jury-must be persuaded that the proper choice has been made. (For a discussion of this task and its importance in a particular case, see my 1979 paper.) The new industrial economics makes possible an approach to model selection that combines the soundest elements of the Harvard and Chicago traditions in industrial economics. Recent work follows Harvard in acknowledging the possibility of markets not well described by either perfect competition or pure monopoly, and it follows Chicago in stressing the value of deductive analysis of explicit economic models. In the past decade, the tools of modern economic theory and, increasingly, modern game theory have been employed to construct and analyze a variety of models of imperfect competition. By emphasizing the construction and use of such models, the new approach encourages the selection of models tailored to be consistent with the relevant evidence and with the general principles of economic analysis. (My 1978 paper provides an example of this approach.) Careful use of modern theory should permit more precise analysis of individual antitrust cases; at the very least it should focus attention on the most important factual questions in each case. Moreover, decisions based on explicit selection of internally consistent models can be expected to be more accurate than those based on tests involving such things as arbitrary market share thresholds derived from judicial precedent, not economic analysis. (This argument is developed in detail in my 1979 paper.) While the new industrial economics has provided a large and varied menu of market models from which an analyst may select, it has not yet developed reliable tools for the empirical analysis of particularindustries that would help one choose models in practice. In my 1978 analysis of the ready-to-eat break-

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 72 NO. 2

IMPERFECT COMPETITION AND PUBLIC POLICY

25

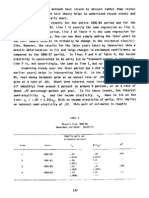

fast cereal industry, for example, I used an explicit, spatial model of rivalry in a differentiated market. That model could be shown by deductive argument to be consistent with the general principles of economic theory, but its consistency with the facts of the case and its superiority to alternative models with different policy implications were not so easily established. I could not draw on a set of proven empirical techniques for testing industry-specific hypotheses about such things as the spatial structure of demand or the existence of significant collusion. One can expect recent advances in theory to contribute to the development of such techniques, however, just as theoretical developments have served to sharpen the tools of empirical investigation in other areas of economics. Hypotheses about the nature of seller conduct may be particularly susceptible to rigorous testing. In an important, pioneering study, Gyoichi Iwata attempts to estimate conjectural variations in an oligopoly with homogeneous products. He also gives tests for Cournot and collusive behavior. Product differentiation requires more complex models, of course. But, as Timothy Bresnahan's impressive recent study of the automobile industry shows, it may also aid in the identification of behavior patterns. Behavioral hypotheses involving investments in entry deterrence may also be rigorously testable. (One might attempt to test formally Learned Hand's conclusion that Alcoa sacrificed current profits by building capacity ahead of demand to discourage entry, for instance.) Application of the new industrial economics to antitrust cases will not be costless, or even cheap. As the technical sophistication of theoretical and empirical analysis in industrial economics rises, the costs of antitrust litigation will rise also. Industry analysis using state of the art techniques will require more human capital and computer time, and it will take more effort to communicate such analysis to noneconomist judges and juries. The sophistication of antitrust decisions will surely rise more slowly than the sophistication of economic analysis and testimony.

II. Normative Analysis of Rules and Remedies

In evaluating alternative rules of law, and often in considering proposed relief in particular cases, one must perform normative analysis. This is generally taken by economists to mean that one must be able to predict efficiency consequences. An explicit concern for economic efficiency has been one of the hallmarks of recent theoretical work in industrial economics, so one might expect the new industrial economics to produce normative analysis useful in developing general rules of law. Such analysis has not yet appeared, however, and there are two basic reasons for doubting that it will appear in the near future. The first reason is visible in Michael Spence's recent description of the analytical approach of the new industrial economics: My instinct as an economist is to study industries on a case-by-case basis, applying and adapting models as appropriate. For those of us who do this kind of work, the differences among industries sometimes seem more important or interesting than the similarities. And thus we are uncomfortable with general rules. That, of course, is not very useful to courts or litigators, who require some general principles or rules on which to hear and argue cases. [p. 58] Rules of law implicitly consist of rules for model selection and policy responses conditional on the model selected. As Spence's description suggests, the new work finds that differences among industries seem so fundamentally complex that simple, universally valid rules for model selection may not exist. If this is correct, it follows that simple, universally valid rules of law cannot be written. There are two ways around this problem in principle. One can explicitly aim for complex rules of law, in which some sets of facts require the sort of unstructured rule-of-reason-like analysis that Spence describes, while others permit straightforward, well-structured policy choice. Alternatively, one can use information about the frequencies with

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26

A EA PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS

MA Y 1982

which various theoretical possibilities actually occur to frame simple rules of law based on generally valid rules for model selection. Both these approaches are difficult enough that one cannot hope for definitive results soon. The second reason for doubting that the new industrial economics will produce general antitrust policy prescriptions in the near future relates to the linkage between models and policy responses. Recent theoretical work has focused on explicit models of imperfect competition, describing markets in which the structural features (like scale economies) that prevent the emergence of perfect competition are taken as givens. The new industrial economics thus recognizes that in many situations, antitrust can only move a market from one imperfect, distorted equilibrium to another. This recognition forces one to confront a particularly difficult class of second best problems when analyzing either general rules or case-specific relief proposals. Second best problems classically arise in the context of antitrust because of distortions in other markets: if apples are monopolized, moving the widget market from monopoly to competition may be inefficient. Antitrust commentators typically refuse to deal with such problems on the reasonable ground that their intractability in practice would induce paralysis. (See, for instance, F. M. Scherer, pp. 28-29.) The models of the new industrial economics indicate clearly that related problems arise because the usual policy option is a move toward competition in some sense, not a move all the way to competition. Thus, because of irremediable imperfections in the widget market itself, movements toward competition there may not enhance efficiency even if all other markets in the economy are purely and perfectly competitive. Such single market, second best problems are harder to ignore. In general, and in the new market models in particular, one needs unrealistically complete knowledge of cost and demand conditions in order to select among imperfectly competitive equilibria. A few examples may serve to illustrate the difficulties encountered in attempting to derive policy prescriptions from the normative

analysis of the new industrial economics. As Richard Posner (1979) notes, the Harvard tradition initially condemned all tying arrangements as providing "leverage" that permitted the multiplication of monopoly positions. Chicago countered that the concept of leverage is without theoretical support, that tying is generally a form of price discrimination, and that ties should be legal because price discrimination is generally efficiency enhancing. But, as Posner notes, recent work shows that price discrimination achieved through tying arrangements may reduce efficiency under some conditions. While some general statements can be made (see my 1981 paper), theoretical analysis suggests the nonexistence of simple tests that one could actually apply in particular cases to determine whether banning tying contracts would enhance efficiency. The recent burst of theoretical work on precommitment to deter entry of new rival sellers and predation to eliminate such sellers provides a second example. (See Avinash Dixit for an overview of this work.) Though a good deal of this analysis has been inspired by debates about antitrust policy toward ".predatory pricing," it has not produced simple policy prescriptions with clear efficiency properties. As Michael Spence notes, recent work shows that "the welfare effects of increasing the stringency of the definition of predatory behavior are far from unambiguous" (p. 57), since such an increase may just induce more investment in entry deterrence. And, as Spence goes on to point out, "... . there are no known, unambiguously beneficial simple rules that can be applied to investments prior to entry..." (p. 60). More generally, recent work indicates that policies that facilitate entry into particular markets may raise or lower net surplus, depending on the exact conditions in those markets. My 1976 paper shows that profitable entry may be inefficient, Joseph Stiglitz (1981) shows that potential competition can lower welfare, and C. C. von Weiszacker (1980) shows that lowering entry barriers may also lower efficiency. Product differentiation adds another layer of complexity. It is difficult to evaluate changes in the set of products produced in general or in particular

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

VOL. 72 NO. 2

IMPERFECT COMPETITION AND PUBLIC POLICY

27

cases because the market almost never induces production of the first best optimal set. (See, for instance, the comparatively weak normative conclusions of my 1978 paper, or the analysis of Roger Koenker and Martin Perry, and the references they cite.) I do not mean to suggest that all recent theoretical work in industrial economics encounters single market, second best problems that prevent the derivation of simple efficiency-enhancing policy prescriptions. The emerging literature on contestable markets is an obvious exception to any such generalization, as that literature shows that many policy issues simplify drastically when sunk costs are relatively unimportant. (See Elizabeth Bailey, Avinash Dixit, and the references they cite.) But, on the whole, recent research indicates that in many areas one cannot confidently predict the efficiency consequences of particular antitrust relief in individual cases without the sort of detailed quantitative information generally necessary to solve second best problems and generally unavailable in antitrust litigation. This research is certainly useful for criticizing existing rules of law that are too simple or based on indefensible economic analysis. And further theoretical and empirical work may yield workable rules of law that are generally productive, despite second best problems, and it may yield techniques for the design of generally productive case-specific relief. It is too soon to tell whether this will occur in many areas, however.

III. Conclusions and Implications

Use of the new industrial economics in individual antitrust cases is likely to raise both the quality and the cost of court decisions on factual issues that arise under current antitrust rules. Unless enforcement of those rules is generally efficiency enhancing, however, that increase in precision may not be worth its cost. And recent theoretical work suggests that in many policy areas (such as tying contracts and entry deterrence) there may exist no workable rules that are generally efficiency enhancing.

As in macroeconomics, increased uncertainty about the consequences of intervention argues against attempts to fine-tune performance. Attempts to make marginal changes in inherently imperfect markets are certain to be expensive and may not increase efficiency even if successful. To the extent that they are concerned with efficiency, the enforcement agencies should thus concentrate their efforts in areas (like price fixing) where it can be convincingly argued that successful cases generally create net benefits. In other areas of the law (like monopolization), they should at least hesitate to bring cases in which there does not exist a specific relief proposal likely to enhance efficiency. Efficiency-enhancing changes in structure or conduct do not necessarily exist everywhere competition is imperfect, and the design of productive relief often requires the careful use of sophisticated economic analysis. Moreover, since the vast majority of antitrust cases are brought by private plaintiffs unconcerned with the economy's overall performance, reexamination of the law may be in order in areas in which workable efficiency-enhancing rules cannot be found. If some existing rules have ambiguous efficiency implications, and if efficiency is the main goal of antitrust policy, vigorous private enforcement of such rules is no more justifiable than vigorous public enforcement. On the other hand, if the real objections to such things as tying contracts and Robinson-Patman style price discrimination have nothing to do with economic efficiency, it is not clear why cases involving such practices should be weighted down with difficult questions (like the importance of monopoly power) that relate mainly to efficiency. Where future theoretical and empirical work does not yield rules of law with good efficiency properties, these and related issues will deserve serious attention. REFERENCES Bailey, ElizabethE., "Contestability and the Design of Regulatory and Antitrust Policy," American Economic Review Proceedings, May 1981, 71, 178-82. Bresnahan, TimothyF., "Competition and Col-

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28

AEA PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS

MA Y 1982

lusion in the American Automobile Industry: The 1955 Price War," mimeo., 1980. Dixit, AvinashK., "Recent Developments in the Theory of Imperfect Competition," American Economic Review Proceedings, May 1982, 72, 12-17. Iwata,Gyoichi,"Measurement of Conjectural Variations in Oligopoly," Econometrica, September 1974, 42, 947-66. RogerW. andPerry,MartinK., " ProdKoenker, uct Differentiation, Monopolistic Competition, and Public Policy," Bell Journal of Economics, Spring 1981, 12, 217-31. Posner, RichardA., "The Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis," University of Pennsylvania Law Review, April 1979, 127, 925-48. Scherer, F. M., Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, 2nd ed., Chicago: Rand McNally, 1980. Schmalensee,Richard,"Is More Competition Necessarily Good?," Industrial Organiza-

tion Review, 1976, 4, 120-21. ."Entry Deterrence in the Ready-toEat Breakfast Cereal Industry," Bell Journal of Economics, Autumn 1978, 9, 305-27. ,"On the Use of Economic Models in Antitrust: The ReaLemon Case," University of Pennsylvania Law Review, April 1979, 127, 994-1050. , " Monopolistic Two-Part Pricing Arrangements," Bell Journal of Economics, Autumn 1981, 11, 445-66. Spence,A. Michael,"Competition, Entry, and Antitrust Policy," in Steven C. Salop, ed., Strategy, Predation, and AntitrustAnalysis, Washington: U.S. Federal Trade Commission, 1981, ch. 2. Stiglitz, Joseph E., " Potential Competition May Reduce Welfare," American Economic Review Proceedings, May 1981, 71, 184-89. C. C., "A Welfare Analysis of von Weizsacker, Barriersto Entry," Bell Journal of Economics, Autumn 1980, 11, 399-420.

This content downloaded on Fri, 1 Feb 2013 20:36:25 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- I-l-ED States: Titative RevieDokumen10 halamanI-l-ED States: Titative ReviePaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- I-l-ED States: Titative RevieDokumen10 halamanI-l-ED States: Titative ReviePaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- CL1 LucasMDUSAop.21-30 PDFDokumen10 halamanCL1 LucasMDUSAop.21-30 PDFPaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- CL1 LucasMDUSAop.11-20 PDFDokumen10 halamanCL1 LucasMDUSAop.11-20 PDFPaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- I-l-ED States: Titative RevieDokumen10 halamanI-l-ED States: Titative ReviePaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- Risk-Taking Channel of Monetary Policy ModelDokumen10 halamanRisk-Taking Channel of Monetary Policy ModelPaul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- CL2 HyunSongShin 1.11-20Dokumen10 halamanCL2 HyunSongShin 1.11-20Paul Rosado OlivosBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Jillian's Student Exploration of TranslationsDokumen5 halamanJillian's Student Exploration of Translationsjmjm25% (4)

- CV Finance GraduateDokumen3 halamanCV Finance GraduateKhalid SalimBelum ada peringkat

- HRU Stowage and Float-free ArrangementDokumen268 halamanHRU Stowage and Float-free ArrangementAgung HidayatullahBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewDokumen6 halamanLesson 6 (New) Medication History InterviewVincent Joshua TriboBelum ada peringkat

- Experiment No. 11 Fabricating Concrete Specimen For Tests: Referenced StandardDokumen5 halamanExperiment No. 11 Fabricating Concrete Specimen For Tests: Referenced StandardRenBelum ada peringkat

- Container sizes: 20', 40' dimensions and specificationsDokumen3 halamanContainer sizes: 20', 40' dimensions and specificationsStylefasBelum ada peringkat

- Sterilization and DisinfectionDokumen100 halamanSterilization and DisinfectionReenaChauhanBelum ada peringkat

- String length recommendations and brace height advice for Uukha bowsDokumen1 halamanString length recommendations and brace height advice for Uukha bowsPak Cik FauzyBelum ada peringkat

- Diabetic Foot InfectionDokumen26 halamanDiabetic Foot InfectionAmanda Abdat100% (1)

- Social Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaDokumen7 halamanSocial Responsibility and Ethics in Marketing: Anupreet Kaur MokhaVlog With BongBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Manajemen IndonesiaDokumen20 halamanJurnal Manajemen IndonesiaThoriq MBelum ada peringkat

- Form PL-2 Application GuideDokumen2 halamanForm PL-2 Application GuideMelin w. Abad67% (6)

- Emergency Order Ratification With AmendmentsDokumen4 halamanEmergency Order Ratification With AmendmentsWestSeattleBlogBelum ada peringkat

- Form 16 PDFDokumen3 halamanForm 16 PDFkk_mishaBelum ada peringkat

- Project Management-New Product DevelopmentDokumen13 halamanProject Management-New Product DevelopmentRahul SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Kargil Untold StoriesDokumen214 halamanKargil Untold StoriesSONALI KUMARIBelum ada peringkat

- Forouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionDokumen14 halamanForouzan MCQ in Error Detection and CorrectionFroyd WessBelum ada peringkat

- Dreams FinallDokumen2 halamanDreams FinalldeeznutsBelum ada peringkat

- GPAODokumen2 halamanGPAOZakariaChardoudiBelum ada peringkat

- The Forum Gazette Vol. 2 No. 23 December 5-19, 1987Dokumen16 halamanThe Forum Gazette Vol. 2 No. 23 December 5-19, 1987SikhDigitalLibraryBelum ada peringkat

- Round Rock Independent School District: Human ResourcesDokumen6 halamanRound Rock Independent School District: Human Resourcessho76er100% (1)

- 2nd YearDokumen5 halaman2nd YearAnbalagan GBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 8, Problem 7PDokumen2 halamanChapter 8, Problem 7Pmahdi najafzadehBelum ada peringkat

- Discover books online with Google Book SearchDokumen278 halamanDiscover books online with Google Book Searchazizan4545Belum ada peringkat

- Syllabus For The Post of ASI - Traffic - WardensDokumen2 halamanSyllabus For The Post of ASI - Traffic - WardensUbaid KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Opportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingDokumen24 halamanOpportunity Seeking, Screening, and SeizingHLeigh Nietes-GabutanBelum ada peringkat

- INDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTDokumen15 halamanINDEX OF 3D PRINTED CONCRETE RESEARCH DOCUMENTAkhwari W. PamungkasjatiBelum ada peringkat

- Category Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiDokumen565 halamanCategory Theory For Programmers by Bartosz MilewskiJohn DowBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1Dokumen11 halamanChapter 1Albert BugasBelum ada peringkat

- Lucid Motors Stock Prediction 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, 2030Dokumen8 halamanLucid Motors Stock Prediction 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, 2030Sahil DadashovBelum ada peringkat