Wound Care With Antibacterial Honey (Medihoney) in Pediatric Hematology

Diunggah oleh

Dwi Ari ShandyDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Wound Care With Antibacterial Honey (Medihoney) in Pediatric Hematology

Diunggah oleh

Dwi Ari ShandyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Support Care Cancer (2006) 14: 9197 DOI 10.

1007/s00520-005-0874-8

SH ORT COMMUNI CATIO N

Arne Simon Kai Sofka Gertrud Wiszniewsky Gisela Blaser Udo Bode Gudrun Fleischhack

Wound care with antibacterial honey (Medihoney) in pediatric hematologyoncology

Received: 3 May 2005 Accepted: 12 July 2005 Published online: 2 August 2005 # Springer-Verlag 2005

A. Simon (*) . K. Sofka . G. Wiszniewsky . G. Blaser . U. Bode . G. Fleischhack Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Childrens Hospital, University of Bonn, Adenauerallee 119, 53113 Bonn, Germany e-mail: asimon@ukb.uni-bonn.de Tel.: +49-228-2873254 Fax: +49-228-2873301

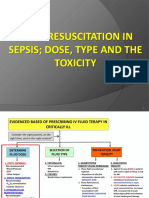

Abstract The physiologic process of wound healing is impaired and prolonged in pediatric patients receiving chemotherapy. Due to profound immunosuppression, wound infection can easily spread and act as the source of sepsis. Referring to in vitro studies, which confirmed the antibacterial potency of special honey preparations against typical isolates of nosocomially acquired wound infections (including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Vancomycin-resistant enterococci) and considering the encouraging reports from other groups, Medihoney has now been used in

wound care at the Department of Pediatric Oncology, Childrens Hospital, University of Bonn for 3 years. Supplemented with clinical data from pediatric oncology patients, this article reviews the scientific background and our promising experience with Medihoney in wound care issues at our institution. To collect and analyze the available experience, we prepare an internet-based data documentation module for pediatric wound care with Medihoney. Keywords Wound care . Pediatric oncology . Honey . MRSA

Introduction

A functional immune system is a prerequisite for the physiological process of wound healing. In pediatric oncology patients, the immune system is often suppressed, and wound healing is impaired to a clinically significant extent for extended periods of time. Obvious reasons for this include: Toxicity of treatment with cytotoxic antineoplastic agents or radiation therapy to the skin and mucous membranes (i.e., high-dose methotrexate, anthracyclines) Persistent or intermittent profound immunosuppression (neutropenia with <500 granulocytes/l for more than 10 days, lymphocytopenia) [1] Malnutrition due to nausea, vomiting and mucositis [2] Microbial super infections (bacteria, fungi, viruses) [35]

can be missing due to immunosuppression [6]. At the Department of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, Childrens Hospital, Medical Center, University of Bonn, antibacterial honey is used for wound care purposes now for 3 years. Supplemented with clinical data from pediatric oncology patients, this article reviews the scientific background and the experience with Medihoney in wound care issues at our institution. To the best of our knowledge, there has not been any prior publication describing the use of honey in pediatric oncology patients. With this case reports, we would like to encourage other oncological treatment centers to use antibacterial honey for wound treatment. An overview of the 16 wound care situations in 14 patients, their underlying illnesses, and outcomes are given in Table 2.

Antibacterial honey for wound treatment

Non-heated honey, processed under controlled pharmacological conditions [7] with proven antibacterial activity, is being increasingly used for the treatment of infected wounds

Table 1 lists a selection of common wound care situations nurses and physicians in pediatric oncology departments are confronted with. It has to be considered that in this patient population, typical clinical signs of infection except for fever

92

Table 1 Selection of common wound care situations in pediatric oncology Dehiscence and infection of surgical wounds (after tumor biopsy or surgery) Ulcers (decubiti) due to tumor cachexia or injuries due to peripheral neuropathy induced by cytotoxic agents (like vincristin) Inflamed or infected catheter entry sites (Broviac, Port) Deep wounds after reservoir explantation, leaving an infected port pocket (prolonged secondary wound healing) Skin necrosis due to extravasation of cytotoxic drugs, septic infections or vasoocclusion in patients with sickle-cell anemia and acute sickle crisis Skin and bone necrosis due to invasive Aspergillosis Ecthyma gangraenosum in patients with Pseudomonas sepsis Impaired and prolonged wound healing after amputation of extremities Anorectal inflammation, dermatitis, fissures, ulcers [45]

low cost, and to high acceptability and feasibility. Local treatment with antibacterial honey usually enjoys a high level of patient acceptance; local pain occurs only rarely [14]. Medihoney (http://www.medihoney.com) is a standard mixture of honeys that has been sterilized but not inactivated through irradiation [24]. Appropriate products, for which the official certification of the European Union as medical device type IIb for wound care (CE certificate) is now available, consist of 100% honey or honey gel (80% honey and hypoallergenic waxes, facilitating a more viscous consistence).

Examples of application in clinical practice

Surgical wound infection According to an interim analysis of the Onkopaed NKI Study (prospective surveillance of nosocomial infections (NI) in pediatric oncology patients, status Apr 03rd 2005, covering a cumulative surveillance period of 46,368 inpatient days) [32], surgical wound infections represent 6% of all NI with an incidence density of 0.28/1,000 inpatient days. Most wounds that were treated with antibacterial honey (Medihoney) in our department were dehiscent or infected surgical wounds, drainage sites as well as secondarily healing deep wounds due to explantation of an infected port reservoir. The first patient treated with Medihoney suffered from an MRSA infection of a drainage site after resection of an abdominal lymphoma. The postoperative phase of wound healing is prolonged in immunocompromised patients. Complete healing can often not be waited for, as the intensity of chemotherapy necessitates the cytotoxic therapy to be continued. Catheter entry sites were often treated with Medihoney Wound Gel on a daily basis and were free of irritation and clear of infection afterwards. Even in a patient suffering from a relapse of acute lymphatic leukemia subjected to high level immunosuppression lasting for months, a deep surgical site infection of a port pocket healed completely without further complications (Fig. 1ac). In our experience, it is possible to guide the oncological patient with a chronic wound through a high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation without secondary complications if Medihoney is used for wound care (Table 2, pt. No. 11 and Fig. 2a,b). Further potential indications for therapy with Medihoney are necrotic skin lesions due to ex3travasation to cytotoxic drugs and superinfected skin lesions in children with eczemas or herpetic lesions [20, 21, 3335]. Ecthyma gangrenosum Ecthyma gangrenosum is a septic skin infiltrate observed in at least a third of all patients suffering from Pseudomonas

[5, 812], ulcers [13, 14], scalds and burns [1519], for herpetic skin lesions and atopic dermatitis [20, 21] as well as for protection of transplants in plastic surgery [22, 23]. Sterilization with gamma radiation inactivates Clostridium spores, which may be contained in honey [24]. For medical purposes, honey is used primarily from bees collecting nectar from Leptospermum spp. (manuka, jellybush), growing in the immediate vicinity of the hives in Australia and New Zealand.1 It has been demonstrated in vitro that the antibacterial effects of this honey are superior to most others [5, 12]. Important mechanisms of antimicrobial activity are the high osmotic potential (supersaturated sugar solution2) [7, 25] and the continuous production of hydrogen peroxide through the enzyme glucose oxidase in low, non-cytotoxic quantities [26]. Although its effects have been documented in vitro, the chemical nature of an additional antibacterial factor contributing to the potent bactericidal activity of this type of honey has not yet been elucidated [7]. Among other effects, honey stimulates the secretion of cytokines from macrophages, migrating into the wound tissue [27]. In particular, the team of Dr. Rose Cooper demonstrated that antibacterial honey shows bactericidal activity against nosocomial bacterial isolates even when diluted down to 5%. Among these bacteria were Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin-resistant en terococci (VRE) as well as Pseudomonas spp. [9, 2831]. Therefore, medical honey appears to be an attractive option for treating MRSA-infected wounds due to its bactericidal activity, to the absence of resistance problems, to

1 The most prominent protagonist of manuka honey from New Zealand and pioneer of investigating its medical applications is Peter C. Molan, University of Waikato, Department of Biological Sciences, see http://honey.bio.waikato.ac.nz. 2 Due to its high osmotic potential, honey facilitates the resolution of edema and keeps the wound moist by mobilizing wound exudate.

93

Table 2 Survey of 15 exemplary wound care situations in pediatric oncology patients successfully managed with Medihoney ID Malignancy/underlying illness (Neutropenia at day 1 of Medihoney treatment1=yes, 2=no) Rhabdomyosarcoma (2) Age Description of the wound (cultured pathogens) Length of treatment with Medihoney Systemic antibiotics during Medihoney treatment (cumulative days) 5d Clinical course

10 (8/12)

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Down syndrome, (1) Hemophilia (2) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia first relapse (2) Wilms tumor relapse (1)

12 (2/12)

3 4

4 (8/12) 14 (2/12)

Infection of the externally growing partially necrotic tumor (S. aureus) Ecthyma gangraenosum right femur, sepsis (P. aeruginosa) Infection of the port pocket (CoNS) Infection of the port pocket (CoNS) Dehiscent thoracotomy wound after resection of pulmonary metastases Drainage wound, infected with MRSA Dehiscent thoracotomy wound after resection of the primary tumor Infected entrance of the Broviac CVAD Dehiscent suture at the port pocket Superficial surgical wound infection (tumor resection) with MRSA Dehiscent superficial wound after Broviac implantation (high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation) Dehiscent drainage wound, after splenectomy Abscess (S. aureus), wound care after surgical drainage Port pocket infection with secondary bacteremia (MRSE)

5d

19 d

18 d

6d 15 d

12 d 10 d before Medihoney 8d

12 (2/12)

13 d

Sterile wound on day 3, healing without further complication Sterile wound on day 4, healing without further complication Sterile wound healing Sterile wound healing, prolonged immunosuppression Sterile wound healing, prolonged immunosuppression Sterile wound healing Sterile wound healing, small keloid Sterile wound healing Sterile wound healing Sterile on day 2, uncomplicated wound healing In spite of severe immunosuppression and grad II skin toxicity: sterile wound, no complications Sterile wound healing Sterile wound healing Sterile wound healing

6 7

Abdominal B cell lymphoma (2) Ewings sarcoma of the chest wall (2) T-non-Hodgkin lymphoma, mediastinal (2) T-non-Hodgkin lymphoma (2) Rhabdomysosarcoma (2)

12 (5/12) 12 (5/12)

17 d 36 d

4d 15 d

2 (2/12)

31 d

12 d

9 10

5 (1/12) 17 (9/12)

30 d 7 d (plus octenidine)

12 d 5d

11

Rhabdomysosarcoma (2)

17 (10/12)

28 d

20 d

12

13

14

T-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system (2) Desmoplastic metastatic small round cell tumor (2) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia second relapse (2)

17

11 d

12 d

24 (10/12)

24 d

8 d before and 6 d during Medihoney 14 d

34 (8/12)

72 d!

94

Table 2 (continued) ID Malignancy/underlying illness (Neutropenia at day 1 of Medihoney treatment1=yes, 2=no) Metastatic osteosarcoma of the right upper extremity after four quarter amputation (2) Wilms tumor relapse (1) Age Description of the wound (cultured pathogens) Length of treatment with Medihoney Systemic antibiotics during Medihoney treatment (cumulative days) 0d Clinical course

15

10 (1/12)

16

12 (2/12)

Dehiscent amputation wound after postoperative chemotherapy with adriamycin Deep dehiscent wound after vascular surgery in the left groin (femoral arterial access)

30 d

Sterile wound healing

52 d

27 d

Sterile wound healing, prolonged immunosuppression

Neutropenia refers to <0.5109 granulocytes/mm3 at day 1 of treatment with Medihoney. Port=totally implanted CVAD CVAD central venous access device, d days, CoNS coagulase-negative staphylococci MRSE Methicillin-resistant CoNS, MRSA Methicillin-resistant S. aureus

aeruginosa sepsis. In the early phase, it appears as a circular erythema with subcutaneous induration and a central vesicle (see Fig. 3a,b). During later stages, it causes profound pain and leads to a central necrosis and a deep ulcer. Often it is localized at multiple sites. Severe cases result in deep wounds, which heal only after weeks of systemic antibiotic treatment. According to our experience, those wounds may be treated with antibacterial honey, which is once daily filled into the wound cavity from day 3 after surgical excision of necrotic tissue. Until then, wounds are kept open with calcium alginates soaked with Octenidin. Similar concepts of treatment are also conceivable after surgical debridement and mash graft transplants of necrotic skin lesions due to meningococcal sepsis [13]. Convenience, adverse effects, and perception by the families Wound care with Medihoney is rather simple and convenient, as the Medihoney dressing is non-adherent, and the wound only has to be cleaned with a rinse of sterile Ringer solution, and sterile compresses before the new honey layer is applied. A sterile gauze and tape dressing is added to cover the wound for the next day and to prevent leakage of honey or wound exudate. The Medihoney dressing should extend to cover any area of inflammation surrounding the wound. Until now, we did not observe adverse effects with the exception of local pain in a single patient with a large and deep wound after abdominal laparotomy. In this patient, wound care with the liquid Medihoney Barrier was ceased, and a change to the more consistent Medihoney Gel was not considered as feasible. Our prospective observational study revealed a high acceptance of patients and their families for

this treatment, which had a positive impact on patient and parent satisfaction.

Discussion

The ideal wound antiseptic (according to Kramer et al. [36]): shows a quick onset of activity and a remanent, broad spectrum effect against bacteria and fungi, even under the unfavorable condition of an exudating, colonized or infected wound (dilution, different protein consistence, chemical inactivation); enhances and accelerates the physiologic process of wound healing (debridement, granulation), even if applied for prolonged periods; does not cause adverse local or systemic effects (allergy, toxicity related to absorption); is of moderate cost even if applied two times daily.

Polyvidone iodine has the advantage of antiseptic properties and is well suited for skin disinfection prior to invasive procedures [36, 37]. However, we have decided against its use in wound care for our patients due to the adverse effects of systemic absorption of iodine on thyroid function. Furthermore, it is difficult to assess the local situation in a wound covered with Polyvidone iodine. Even though Octenidin does have some elevated cytotoxic effects in vitro relative to iodophores or polyhexanide [14, 36], it is our first choice for antiseptic treatment of infected wounds within the first 48 h. We switch to antibacterial honey (Medihoney) as soon as possible. Later on, wounds are rinsed with sterile Ringer solution during each daily dressing change with non-touch, sterile techniques and systemic analgosedation if necessary [13].

95

Fig. 2 a, b Chronic superficial wound (6 cm diameter), treated with Medihoney through a high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation without secondary complications

Fig. 1 ac Deep surgical site infection of a port pocket, treated with Medihoney complete healing without further complications despite prolonged immunosuppression

According to scientific literature and clinical experience, antibacterial honey (Medihoney) seems to fulfill most of the above-mentioned requirements of an ideal antiseptic in wound care. The only open question for Medihoney is the residence time needed to kill bacteria in a colonized wound, which is supposed to be less than 5 min for Octenidin or Polyvidone iodine. Theoretical adverse reactions such as anaphylaxis or systemic toxicity (i.e., hyperglycemia in diabetic patients) have not been reported so far. Nevertheless, meticulous clinical observation and documentation should ensure that severe adverse events related to the use of honey in wound care are immediately reported and published, when such a situation arises. Complex wounds and wounds of immunocompromised patients should only be treated under professional medical supervision. The additional administration of systemic antibiotics (see Table 2) is often necessary in pediatric

Fig. 3 a, b Ecthyma gangraenosum in a leukemia patient with P. aeruginosa sepsis. a Early phase with circular erythema, subcutaneous induration and a central vesicle. b Later stage central necrosis and a deep ulcer, covered with Medihoney

96

oncology patients during periods of profound neutropenia (<0.5109/l). Even the best antiseptic, anti-edema, and granulation stimulating local treatment does not abrogate the need of early surgical drainage of retentions and the early debridement of necrotic wound areas [8, 12]. Vardi et al. observed the complete healing of complicated, deep sternal wound infections with honey in nine neonates and infants after surgical intervention for congenital heart disease within 21 days of treatment. The majority of these patients had been treated unsuccessfully with local antiseptics and systemic antibiotics for more than 14 days (Pseudomonas, S. aureus, MRSA, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter spp.). For six of nine patients, the antibiotic treatment was finished at the beginning of wound care with honey [44]. There are many impressive case studies but only a few controlled trials [10, 11, 3941] concerning the use of honey for wound care. In superficial burn wounds, but not for deep necrotic burns [17], an advantage of honey relative to other applied remedies [18, 38] was shown. Johnson et al. performed a randomized, controlled trial comparing the prophylactic effect of thrice-weekly exit-site application of Medihoney versus mupirocin on infection rates in patients who were receiving hemodialysis via tunneled, cuffed central venous catheters [42]. A total of 101 patients were enrolled. The incidences of catheter-associated bacteremias in honey-treated (n=51) and mupirocintreated (n=50) patients were comparable (0.97 versus 0.85 episodes per 1,000 catheter-days, respectively; not significant). The authors concluded that thrice-weekly application of standardized antibacterial honey to hemodialysis

catheter exit sites was safe, cheap, and effective and that with local Medihoney, the problem of resistance induction against mupirocin can be circumvented. Biswal et al. investigated the use of honey in 40 adult patients with head and neck cancer. In the study arm, patients were advised to stake 20 ml of pure honey 15 min before, 15 min after and 6 h post-radiation therapy. There was a significant reduction in the symptomatic grade 3/4 mucositis among honeytreated patients compared to controls; i.e., 20% versus 75% (p<0.001). Fifty-five percent of patients treated with topical honey showed no change or a positive gain in body weight compared to 25% in the control arm (p=0.053); the majority lost weight. The authors concluded that topical application of natural honey is a simple and cost-effective treatment in radiation mucositis, which warrants further investigation in a multi-center randomized trial [43]. In the near future, an internet-based documentation system with standardized items for the documentation of wound healing in children treated with Medihoney will be available. The main objective of this database will be the cumulative analysis of prospectively documented treatment experiences from many pediatric centers. The results will be sent to the participating centers and published in the medical literature. Prospective randomized and controlled studies comparing the use of Medihoney with conventional regimes of wound care are desirable, but double-blinding of honey use in wound care is not possible in clinical practice. Potential concomitant and confounding treatments such as administration of antibiotics or local antiseptics as well as the duration of neutropenia have to be carefully controlled for by randomization.

References

1. Larson E, Nirenberg A (2004) Evidence-based nursing practice to prevent infection in hospitalized neutropenic patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 31(4):717725 2. Kostler WJ, Hejna M, Wenzel C, Zielinski CC (2001) Oral mucositis complicating chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy: options for prevention and treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 51(5): 290315 3. Edwards R, Harding KG (2004) Bacteria and wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis 17(2):9196 4. Wysocki AB (2002) Evaluating and managing open skin wounds: colonization versus infection. AACN Clin Issues 13(3):382397 5. Al-Waili NS (2004) Investigating the antimicrobial activity of natural honey and its effects on the pathogenic bacterial infections of surgical wounds and conjunctiva. J Med Food 7(2):210222 6. Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Doebbeling BN (2001) The validity of the clinical signs and symptoms used to identify localized chronic wound infection. Wound Repair Regen 9(3):178186 7. Zaghloul AA, el-Shattawy HH, Kassem AA, Ibrahim EA, Reddy IK, Khan MA (2001) Honey, a prospective antibiotic: extraction, formulation, and stability. Pharmazie 56(8):643647 8. Ahmed AK, Hoekstra MJ, Hage JJ, Karim RB (2003) Honey-medicated dressing: transformation of an ancient remedy into modern therapy. Ann Plast Surg 50(2):143147; discussion 78 9. Cooper RA, Molan PC, Harding KG (1999) Antibacterial activity of honey against strains of Staphylococcus aureus from infected wounds. J R Soc Med 92(6):283285 10. Cooper RA, Molan PC, Krishnamoorthy L, Harding KG (2001) Manuka honey used to heal a recalcitrant surgical wound. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 20(10):758759 11. Molan PC, Betts JA (2004) Clinical usage of honey as a wound dressing: an update. J Wound Care 13(9):353356 12. Namias N (2003) Honey in the management of infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 4(2):219226 13. Dunford C, Cooper R, Molan P (2000) Using honey as a dressing for infected skin lesions. Nurs Times 96(14 Suppl): 79 14. Dunford CE, Hanano R (2004) Acceptability to patients of a honey dressing for non-healing venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 13(5):193197 15. Honari S (2004) Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 16(1):111 16. Merz J, Schrand C, Mertens D, Foote C, Porter K, Regnold L (2003) Wound care of the pediatric burn patient. AACN Clin Issues 14(4):429441

97

17. Subrahmanyam M (1999) Early tangential excision and skin grafting of moderate burns is superior to honey dressing: a prospective randomised trial. Burns 25(8):729731 18. Subrahmanyam M (1993) Honey impregnated gauze versus polyurethane film (OpSite) in the treatment of burns a prospective randomised study. Br J Plast Surg 46(4):322323 19. Subrahmanyam M (1991) Topical application of honey in treatment of burns. Br J Surg 78(4):497498 20. Al-Waili NS (2001) Therapeutic and prophylactic effects of crude honey on chronic seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff. Eur J Med Res 6(7):306308 21. Al-Waili NS (2004) Topical honey application vs. acyclovir for the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex lesions. Med Sci Monit 10(8): MT94MT98 22. Abenavoli FM, Corelli R (2003) Honey cream. Ann Plast Surg 50(1):105106 23. Subrahmanyam M (1993) Storage of skin grafts in honey. Lancet 341 (8836):6364 24. Molan PC, Allen KL (1996) The effect of gamma-irradiation on the antibacterial activity of honey. J Pharm Pharmacol 48(11):12061209 25. Moore G, Smith L, Campbell F, Seers K, McQauy H, Moore H (2001) Systematic review of the use of honey as a wound dressing. BMC Complement Altern Med 1(2 (4 June 2001)):http:// www.biomedcentral.com/content/ pdf/1472-6882-1-2.pdf 26. Bang LM, Buntting C, Molan P (2003) The effect of dilution on the rate of hydrogen peroxide production in honey and its implications for wound healing. J Altern Complement Med 9(2):267273

27. Tonks AJ, Cooper RA, Jones KP, Blair S, Parton J, Tonks A (2003) Honey stimulates inflammatory cytokine production from monocytes. Cytokine 21 (5):242247 28. Cooper R, Molan P (1999) The use of honey as an antiseptic in managing Pseudomonas infection. J Wound Care 8(4):161164 29. Cooper RA, Halas E, Molan PC (2002) The efficacy of honey in inhibiting strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from infected burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 23(6):366370 30. Cooper RA, Molan PC (1999) Honey in wound care. J Wound Care 8(7):340 31. Cooper RA, Molan PC, Harding KG (2002) The sensitivity to honey of Gram-positive cocci of clinical significance isolated from wounds. J Appl Microbiol 93(5):857863 32. Simon A, Fleischhack G, Hasan C, Bode U, Engelhart S, Kramer MH (2000) Surveillance for nosocomial and central line-related infections among pediatric hematologyoncology patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 21(9):592596 33. Lubbe J (2003) Secondary infections in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 4(9):641654 34. Ricci G, Patrizi A, Neri I, Bendandi B, Masi M (2003) Frequency and clinical role of Staphylococcus aureus overinfection in atopic dermatitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol 20(5):389392 35. Alarcon A, Pena P, Salas S, Sancha M, Omenaca F (2004) Neonatal early onset Escherichia coli sepsis: trends in incidence and antimicrobial resistance in the era of intrapartum antimicrobial prophylaxis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 23(4): 295299 36. Kramer A, Daeschlein G, Kammerlander G, Abdriessen A, Aspck C, Bergemann R et al (2004) Consensus recommendation for the choice of antiseptic agents in wound care (Article in German). Hyg Med 29(5):147157

37. Reimer K, Wichelhaus TA, Schafer V, Rudolph P, Kramer A, Wutzler P et al (2002) Antimicrobial effectiveness of povidone-iodine and consequences for new application areas. Dermatology 204(Suppl 1):114120 38. Subrahmanyam M (1998) A prospective randomised clinical and histological study of superficial burn wound healing with honey and silver sulfadiazine. Burns 24(2):157161 39. Molan P, Betts J (2000) Using honey dressings: the practical considerations. Nurs Times 96(49):3637 40. Molan PC (2002) Re-introducing honey in the management of wounds and ulcerstheory and practice. Ostomy/Wound Manage 48(11):2840 41. Molan PC (1999) The role of honey in the management of wounds. J Wound Care 8(8):415418 42. Johnson DW, van Eps C, Mudge DW, Wiggins KJ, Armstrong K, Hawley CM et al (2005) Randomized, controlled trial of topical exit-site application of honey (Medihoney) versus mupirocin for the prevention of catheter-associated infections in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:14561462 43. Biswal BM, Zakaria A, Ahmad NM (2003) Topical application of honey in the management of radiation mucositis: a preliminary study. Support Care Cancer 11(4):242248 44. Vardi A, Barzilay Z, Linder N, Cohen HA, Paret G, Barzilai A (1998) Local application of honey for treatment of neonatal postoperative wound infection. Acta Paediatr 87(4):429432 45. Lehrnbecher T, Marshall D, Gao C, Chanock SJ (2002) A second look at anorectal infections in cancer patients in a large cancer institute: the success of early intervention with antibiotics and surgery. Infection 30(5):272276

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Clinically Relevant Mycoses: A Practical ApproachDari EverandClinically Relevant Mycoses: A Practical ApproachElisabeth PresterlBelum ada peringkat

- Effect of Ozone Therapy Dressing Technique On The Healing Process of Recent 2nd Degree BurnsDokumen24 halamanEffect of Ozone Therapy Dressing Technique On The Healing Process of Recent 2nd Degree BurnsIOSRjournalBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotic SsiDokumen6 halamanAntibiotic Ssim8wyb2f6ngBelum ada peringkat

- Artigo Terapia Alvo 1Dokumen9 halamanArtigo Terapia Alvo 1fga.crislainebernardino01Belum ada peringkat

- PIIS1198743X19303829Dokumen10 halamanPIIS1198743X19303829YeseniaBelum ada peringkat

- Sensitivity of Microorganisms To Local Antibacterial Preparations Used in Purulent Inflammatory Diseases of The Maxillofacial Region in ChildrenDokumen4 halamanSensitivity of Microorganisms To Local Antibacterial Preparations Used in Purulent Inflammatory Diseases of The Maxillofacial Region in ChildrenCentral Asian StudiesBelum ada peringkat

- Revolutionizing Non-Conventional Wound Healing Using Honey by Simultaneously Targeting Multiple Molecular Mechanisms PDFDokumen10 halamanRevolutionizing Non-Conventional Wound Healing Using Honey by Simultaneously Targeting Multiple Molecular Mechanisms PDFAbdoBelum ada peringkat

- Negative Pressure Wound TherapyDokumen9 halamanNegative Pressure Wound TherapySuharyonoBelum ada peringkat

- Osteomyelitis: Aidan Hogan Volkmar G. Heppert Arnold J. SudaDokumen14 halamanOsteomyelitis: Aidan Hogan Volkmar G. Heppert Arnold J. Sudavijay SaxsenaBelum ada peringkat

- Management Ulkus KorneaDokumen8 halamanManagement Ulkus Korneaalifah syarafinaBelum ada peringkat

- Recent Trends On Wound Management: New Therapeutic Choices Based On Polymeric CarriersDokumen24 halamanRecent Trends On Wound Management: New Therapeutic Choices Based On Polymeric Carriersrozh rasulBelum ada peringkat

- Referat - CHRONIC WOUNDDokumen19 halamanReferat - CHRONIC WOUNDAfifah Syifaul UmmahBelum ada peringkat

- Dermatology For The General SurgeonDokumen24 halamanDermatology For The General SurgeonAnita HerreraBelum ada peringkat

- Fever A ND Ne Utrop e Nia in Pe Diatric Patie NT S With C A NcerDokumen20 halamanFever A ND Ne Utrop e Nia in Pe Diatric Patie NT S With C A NcerFifin m saidBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis PDFDokumen3 halamanAntibiotic Prophylaxis PDFPadmanabha GowdaBelum ada peringkat

- Pi Is 2090074012000357Dokumen6 halamanPi Is 2090074012000357Diggi VioBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Therapy in Equine Wound ManagementDokumen13 halamanMedical Therapy in Equine Wound ManagementDanahe CastroBelum ada peringkat

- Isid Guide Preparing The Patient For Surgery-1Dokumen16 halamanIsid Guide Preparing The Patient For Surgery-1Prunaru BogdanBelum ada peringkat

- Wound Infection SepsisDokumen27 halamanWound Infection SepsisDonny Artya KesumaBelum ada peringkat

- Luka 2 PDFDokumen6 halamanLuka 2 PDFBarryBelum ada peringkat

- The Course of The Wound Process in Purulent-Inflammatory Diseases of The Maxillofacial RegionDokumen5 halamanThe Course of The Wound Process in Purulent-Inflammatory Diseases of The Maxillofacial RegionCentral Asian StudiesBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotics 10 00918 v2Dokumen14 halamanAntibiotics 10 00918 v2Laiz GatinhaBelum ada peringkat

- Infeksi Dalam OrthopaediDokumen35 halamanInfeksi Dalam OrthopaediFarry DoankBelum ada peringkat

- St. Louis University Institute of Health and Biomedical SciencesDokumen39 halamanSt. Louis University Institute of Health and Biomedical SciencesMind BlowerBelum ada peringkat

- Cry Op Reserved Amniotic MembraneDokumen26 halamanCry Op Reserved Amniotic MembraneSangeeta SehrawatBelum ada peringkat

- Jid 2008117 ADokumen7 halamanJid 2008117 ARistiana Suci d'KemponBelum ada peringkat

- Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDokumen6 halamanPreoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAshen DissanayakaBelum ada peringkat

- Microbiome and Probiotics in Acne Vulgaris-A Narrative ReviewDokumen11 halamanMicrobiome and Probiotics in Acne Vulgaris-A Narrative ReviewVanBelum ada peringkat

- Surgical Site InfectionsDokumen22 halamanSurgical Site InfectionsSheryl DurrBelum ada peringkat

- Profilaxis AntiibioticaDokumen6 halamanProfilaxis AntiibioticaAndrés RezucBelum ada peringkat

- Preoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis StatPearls NCBI BookshelfDokumen1 halamanPreoperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis StatPearls NCBI BookshelfJEAN BAILEY RAMOS ROXASBelum ada peringkat

- The Susceptibility of Pathogens Associated With Acne Vulgaris To AntibioticsDokumen7 halamanThe Susceptibility of Pathogens Associated With Acne Vulgaris To AntibioticsMuhammad AdiBelum ada peringkat

- Eficacy of Cryotherapy in The Prevention of Oral Mucosistis inDokumen15 halamanEficacy of Cryotherapy in The Prevention of Oral Mucosistis inPaola GilBelum ada peringkat

- Nutrients 14 04940 v3Dokumen15 halamanNutrients 14 04940 v3Tamires SantanaBelum ada peringkat

- A New Approach To Local Burn Wound Care: Moist Exposed Therapy. A Multiphase, Multicenter StudyDokumen9 halamanA New Approach To Local Burn Wound Care: Moist Exposed Therapy. A Multiphase, Multicenter StudyNur Sidiq Agung SBelum ada peringkat

- Heim 2017Dokumen13 halamanHeim 2017Muhamad SaifuddinBelum ada peringkat

- Antimicrobial Stewardship in The Intensive Care Unit, 2023Dokumen10 halamanAntimicrobial Stewardship in The Intensive Care Unit, 2023Jonathan Fierro MedinaBelum ada peringkat

- Mucormycosis in Immunocompetent Patients - A Case-Series of Patients With Maxillary Sinus Involvement and A Critical Review of The LiteratureDokumen8 halamanMucormycosis in Immunocompetent Patients - A Case-Series of Patients With Maxillary Sinus Involvement and A Critical Review of The LiteratureAnoop SinghBelum ada peringkat

- AFMM2023 - 5 - Antibacterial Electrospun Nanofibrous Materials For Wound HealingDokumen23 halamanAFMM2023 - 5 - Antibacterial Electrospun Nanofibrous Materials For Wound Healingmaolei0101Belum ada peringkat

- Surgical Site Infections: Epidemiology, Microbiology and PreventionDokumen8 halamanSurgical Site Infections: Epidemiology, Microbiology and Preventionm8wyb2f6ngBelum ada peringkat

- Does An Antimicrobial Incision Drape Prevent.15Dokumen9 halamanDoes An Antimicrobial Incision Drape Prevent.15Jimenez-Espinosa JeffersonBelum ada peringkat

- Antibiotic Selection GuideDokumen37 halamanAntibiotic Selection GuideAbanoub Nabil100% (1)

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Blepharoplasty - Review of The Current Literature 2017Dokumen5 halamanAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Blepharoplasty - Review of The Current Literature 2017María Alejandra Rojas MontenegroBelum ada peringkat

- Bioelectric DressingDokumen27 halamanBioelectric DressingEsq. Nelson OduorBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Method To Remove Wound Bacteria Using Woundwand Bipolar RFA NusbaumDokumen7 halamanEffective Method To Remove Wound Bacteria Using Woundwand Bipolar RFA NusbaumBob RiouxBelum ada peringkat

- Laskin The Use of Prophylactic AntibioticsDokumen6 halamanLaskin The Use of Prophylactic Antibioticsapi-265532519Belum ada peringkat

- 162 Dham 8 1999Dokumen6 halaman162 Dham 8 1999Nur Sidiq Agung SBelum ada peringkat

- Faecal Microbiota Transplantation in The Treatment of C - 2020 - Human Microbiome JournalDokumen5 halamanFaecal Microbiota Transplantation in The Treatment of C - 2020 - Human Microbiome Journalbig.ben.bar.123Belum ada peringkat

- KeratitisDokumen21 halamanKeratitistifano_arian9684Belum ada peringkat

- Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Neurosurgery Adult and Paediatric PatientsDokumen6 halamanSurgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis Neurosurgery Adult and Paediatric PatientsPraveen PadalaBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Prevention of Wound Infection After Lichtenstein Open Mesh Repair of Primary Inguinal HerniaDokumen7 halamanThe Role of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Prevention of Wound Infection After Lichtenstein Open Mesh Repair of Primary Inguinal Herniaيحيى الجبليBelum ada peringkat

- Mohamed Omaia, Maged Negm, Yousra Nashaat, Nehal Nabil, Amal OthmanDokumen11 halamanMohamed Omaia, Maged Negm, Yousra Nashaat, Nehal Nabil, Amal OthmancarlosBelum ada peringkat

- Ann Maxillofac SurgDokumen16 halamanAnn Maxillofac SurgVenter CiprianBelum ada peringkat

- Molecules 26 05723 v4Dokumen15 halamanMolecules 26 05723 v4Michael MichaelBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S1877056817303389 MainDokumen6 halaman1 s2.0 S1877056817303389 MainAndreiMunteanuBelum ada peringkat

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation Combined With Antiviral and Steroid Therapy For Herpes Necrotizing Stromal KeratitisDokumen7 halamanAmniotic Membrane Transplantation Combined With Antiviral and Steroid Therapy For Herpes Necrotizing Stromal KeratitisnelyBelum ada peringkat

- Dermatitis HoneyDokumen10 halamanDermatitis HoneyAdhi Galuh AdhetyaBelum ada peringkat

- Post Caesarean Surgical Site Infections 2Dokumen6 halamanPost Caesarean Surgical Site Infections 2saryindrianyBelum ada peringkat

- Medical Mycology Case Reports: SciencedirectDokumen5 halamanMedical Mycology Case Reports: SciencedirectDr.Sudarsan SenBelum ada peringkat

- Extrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent PersonsDokumen9 halamanExtrapulmonary Infections Associated With Nontuberculous Mycobacteria in Immunocompetent Personsrajesh Kumar dixitBelum ada peringkat

- Severe Sepsis&Septic Shock in Pediatrics.: Abdel Razzaq Abu Mayaleh, MDDokumen27 halamanSevere Sepsis&Septic Shock in Pediatrics.: Abdel Razzaq Abu Mayaleh, MDlotskiBelum ada peringkat

- Multi Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDokumen40 halamanMulti Organ Dysfunction SyndromeDr. Jayesh PatidarBelum ada peringkat

- Neonatal SepsisDokumen39 halamanNeonatal SepsisBryan KernsBelum ada peringkat

- ShockDokumen30 halamanShockvinnu kalyanBelum ada peringkat

- Inpatient Medicine Quick Start GuideDokumen35 halamanInpatient Medicine Quick Start GuideStefan SavicBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Biologic CrisisDokumen385 halamanAcute Biologic CrisisSheryl Ann Barit PedinesBelum ada peringkat

- Jurnal Kritis 6 PDFDokumen5 halamanJurnal Kritis 6 PDFEndah Novianti SoenarsinBelum ada peringkat

- NICU 2021clinical Reference Manual For Advanced Neonatal Care FINALDokumen254 halamanNICU 2021clinical Reference Manual For Advanced Neonatal Care FINALTewodros Demeke100% (7)

- BY DR Muhammad Akram M.C.H.JeddahDokumen32 halamanBY DR Muhammad Akram M.C.H.JeddahMuhammad Akram Qaim KhaniBelum ada peringkat

- Pato Sakit Kritis PDFDokumen44 halamanPato Sakit Kritis PDFrsia fatimahBelum ada peringkat

- And Protection of Renal Function in The Intensive Care Unit - Update 2017Dokumen20 halamanAnd Protection of Renal Function in The Intensive Care Unit - Update 2017Edson MarquesBelum ada peringkat

- Webinar 10 12 17 PDFDokumen73 halamanWebinar 10 12 17 PDFDanielaGarciaBelum ada peringkat

- 37 - Shock in ObstetricsDokumen22 halaman37 - Shock in Obstetricsdr_asaleh90% (10)

- Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Study of Nursing CareDokumen12 halamanAcute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Study of Nursing CarenasimhsBelum ada peringkat

- Emergency Room ThesisDokumen8 halamanEmergency Room Thesisstephanieclarkolathe100% (2)

- Medicare Inpatient 2017Dokumen8.939 halamanMedicare Inpatient 2017Shashi Shirke100% (1)

- Paeds Notes (GPatil) - 221109 - 175007 - 221111 - 184922Dokumen108 halamanPaeds Notes (GPatil) - 221109 - 175007 - 221111 - 184922Rushikesh SonkeBelum ada peringkat

- Hammer PDFDokumen12 halamanHammer PDFDidik HariadiBelum ada peringkat

- Preceptor: DR Edwin Haposan Martua SP - An. M.Kes AIFO Khilda Zakiyyah Saadah 2014730047)Dokumen15 halamanPreceptor: DR Edwin Haposan Martua SP - An. M.Kes AIFO Khilda Zakiyyah Saadah 2014730047)KhildaZakiyyahSa'adahBelum ada peringkat

- Fluid Resuscitation - The Evidence PDFDokumen54 halamanFluid Resuscitation - The Evidence PDFrsia fatimahBelum ada peringkat

- The Pathophysiology of Sepsis Associated Aki17Dokumen20 halamanThe Pathophysiology of Sepsis Associated Aki17Melina ToralesBelum ada peringkat

- Sirs & ModsDokumen26 halamanSirs & Modsnerlyn silao50% (2)

- DBM-DOH jc2022-0002Dokumen18 halamanDBM-DOH jc2022-0002Drop ThatBelum ada peringkat

- Nueva Ecija University of Science And: A Case Analysis of Acute Conditions of The NeonatesDokumen68 halamanNueva Ecija University of Science And: A Case Analysis of Acute Conditions of The NeonatesShane PangilinanBelum ada peringkat

- Management of The Patient With A Burn InjuryDokumen43 halamanManagement of The Patient With A Burn InjuryAshraf HusseinBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Hemodialysis PrescriptionDokumen15 halamanAcute Hemodialysis PrescriptionsstdocBelum ada peringkat

- Self Assesment Issues 2019 20 21 MCQs With Answers Pediatrics andDokumen92 halamanSelf Assesment Issues 2019 20 21 MCQs With Answers Pediatrics andwalaa mousaBelum ada peringkat

- Dr. Dian Kusumaningrum - PRESENTASI JCCA-ANTIBIOTIC DOSING IN CRITICALLY ILLDokumen31 halamanDr. Dian Kusumaningrum - PRESENTASI JCCA-ANTIBIOTIC DOSING IN CRITICALLY ILLRestu TriwulandaniBelum ada peringkat

- Sepsis UpdatedDokumen4 halamanSepsis Updatedapi-535481376Belum ada peringkat

- Certified Coding Specialist CCS Exam Preparation OCRDokumen319 halamanCertified Coding Specialist CCS Exam Preparation OCRKian Gonzaga100% (32)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Dari EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Penilaian: 3 dari 5 bintang3/5 (1)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDari EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (82)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDDari EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (3)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDari EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (404)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDari EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (32)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDari EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BePenilaian: 2 dari 5 bintang2/5 (1)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesDari EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (1412)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDari EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsBelum ada peringkat

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDari EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (4)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDari EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (1)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (42)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDari EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearDari EverandThe Comfort of Crows: A Backyard YearPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (23)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossDari EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (6)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityDari EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (6)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDari EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (254)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Dari EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (110)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceDari EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern SciencePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (51)

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsDari EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (39)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlDari EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (60)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingDari EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1138)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDari EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (328)