Groups Face The Conundrum of Cyber Crime - FT

Diunggah oleh

hcukiermanJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Groups Face The Conundrum of Cyber Crime - FT

Diunggah oleh

hcukiermanHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

20/3/2014

Groups face the conundrum of cyber crime - FT.com

By continuing to use this site you consent to the use of cookies on your device as described in our cookie policy unless you have disabled them. You can change your cookie settings at any time but parts of our site will not function correctly without them.

Home

Video

World

Interactive

Companies

Blogs News feed

Markets

Alphaville

Global Economy

beyondbrics Portfolio

Lex

Special Reports

Comment

In depth

Management

Life & Arts

Tools

Todays Newspaper

February 24, 2014 6:02 am

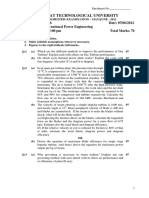

Groups face the conundrum of cyber crime

By Sam Jones

Late last year, UK authorities helped to organise a cyber war game for institutions in Londons financial district, directing the banks, insurers, asset managers and big businesses of the city to simulate the impact on their operations of a debilitating cyber assault. While many of the players in the game no actual assets were involved demonstrated that they had defensive plans in place and often quite sophisticated technical knowhow, they also highlighted a major problem. Not a single one of the participants in operation Waking Shark II, as the scenario was dubbed, thought, during the course of their attack, to report their problems to the police. The scenario highlighted one of the biggest problems in the cyber security world: how is online and computer crime policed, and, moreover, how should it be? Many of the participants [in the city cyber war game] had little or no understanding of when criminal offences were being committed, says Adrian Culley, former detective at Scotland Yards cyber crime unit and now a technical consultant with Damballa, a cyber security consultancy. Given we have had the Computer Misuse Act for 25 years in the UK, its surprising, but we obviously have some way to go still, he adds. Ultimately, there is no such thing as cyber crime, just crime. Just like you dont really hear questions of if someone is computer literate or not these days, I think the notion of cyber crime will fade. In 100 years time. Itll be as if Sherlock Holmes had talked about electric crimes. The nub of the problem is that, for many organisations, cyber crime still seems so intangible. For big businesses such as banks, cyber crimes are all too easy to write off as a marginal cost of doing business in the modern world. A bank suffering from a physical robbery, for example, has a site from which money is stolen and staff there whose responsibility is specific for the security of that site. Doing nothing is not really an option. An attack against a whole organisation though particularly an organisation as large as a bank is far harder to feel or care about, if the relative impact is far smaller. Even if the same or more money is stolen in absolute terms. If the first hurdle is Likewise, when an act against a business involves the theft of data be it intellectual property, or customers

1/2

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/61176e18-923e-11e3-8018-00144feab7de.html?siteedition=intl#axzz2wWPOJwV8

20/3/2014

Groups face the conundrum of cyber crime - FT.com

reporting and detection, then the second even larger hurdle facing the policing of cyber crime is attribution

personal data it is also hard to feel the impact. According to security chiefs, hundreds of major businesses have their IP stolen without ever knowing about it. Cyber crime has numerous other forms too, increasingly being exploited by criminals: propagating false news to manipulate share prices; gaining inside information on merger deals or major share transactions and capital raisings.

The pace of technology change and the cyber threats that come with it are only going to accelerate, everything from critical infrastructure to theeconomic well being of nations and companies assets is a potential target, says Mark Brown, director of information security at EY. If the first hurdle is reporting and detection, then the second even larger hurdle facing the policing of cyber crime is attribution. Tracking down attacks, in itself a hard enough endeavour, is only the beginning of the problem. Attackers often take over other peoples computers to use as platforms sometimes making the ultimate perpetrator of the crime untraceable. Even when an attacker is located, the chances are they will be based in a foreign country. And, at least according to where most attacks are currently sourced too, those countries are not necessarily likely to co-operate in the pursuit of suspects. The impact of international regulation, or in fact the absence of it, is in my view the next big issue in the fight against the cyber threat, says Mr Brown. Currently, even if a company can identify where an attack comes from there is little to no international legislation or treaties that allow prosecution to take place or help companies to respond. What we need is international bodies or specific initiatives that will ensure that everybody plays by the rules. In his recent trip to China, for example, the UK prime minister called for an International Cyber Citizenship which is an idea worth exploring. Even when local law enforcement agencies are minded to do so, the task of linking an individual to crimes committed on a specific machine is in itself a significant legal challenge. It is little wonder then, that where businesses have started to grapple with the issues of cyber security, they have focused heavily on prevention of attacks and ensuring resilience. For now, this is an acceptable status quo. But as many security experts particularly in government are increasingly aware, it is fragile. The nature of cyber attacks mean they have the potential to be hugely disruptive, and not just from a purely monetary point of view, but a systemic one too. A bank that suffers a breach involving the loss of pennies from tens of thousands of separate accounts, for example, is one issue. A bank that suffers an attack where hundreds of depositors lose everything, though, risks far greater reputational damage even a run, where unaffected clients panic to withdraw their money and stash it elsewhere. Likewise for other businesses, attacks large enough to cause lasting and sustained damage are mostly regarded as hypothetical in spite of evidence to the contrary. An attack like that on Saudi Aramco which in 2012 suffered a huge cyber assault apparently aimed at stalling production and wiping out its computer systems is more and more likely on a large western business than ever before. Policing such a large-scale attack or rather, providing a credible deterrence to it is an issue that no government let alone domestic law enforcement agency has yet addressed.

RELATED TOPICS United Kingdom, Global terror

Printed from: http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/61176e18-923e-11e3-8018-00144feab7de.html Print a single copy of this article for personal use. Contact us if you wish to print more to distribute to others. THE FINANCIAL TIMES LTD 2014 FT and Financial Times are trademarks of The Financial Times Ltd.

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/61176e18-923e-11e3-8018-00144feab7de.html?siteedition=intl#axzz2wWPOJwV8

2/2

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Empiricism and Its FallaciesDokumen7 halamanEmpiricism and Its FallacieshcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Environments - Digital Livro Humboldt PDFDokumen278 halamanEnvironments - Digital Livro Humboldt PDFhcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Kreimer Vessuri Sts Latino PDFDokumen22 halamanKreimer Vessuri Sts Latino PDFhcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Meet Walter Pitts, The Homeless Genius Who Revolutionized Artificial IntelligenceDokumen14 halamanMeet Walter Pitts, The Homeless Genius Who Revolutionized Artificial IntelligencehcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Future and Past of Information TechnologyDokumen7 halamanFuture and Past of Information TechnologyhcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- HeterogeneitiesDokumen13 halamanHeterogeneitieshcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- The Elusive Theory of EverythingDokumen4 halamanThe Elusive Theory of EverythinghcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Time To Leave GDP BehindDokumen3 halamanTime To Leave GDP BehindhcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Fiabudapest Final ReportDokumen65 halamanFiabudapest Final ReporthcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Faculty Advisory Council Memorandum On Journal Pricing THE HARVARD LIBRARY TRANSITIONDokumen4 halamanFaculty Advisory Council Memorandum On Journal Pricing THE HARVARD LIBRARY TRANSITIONhcukiermanBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- TNEB vacancy cut-off datesDokumen7 halamanTNEB vacancy cut-off dateswinvenuBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- 1017 Daa Aa Aa Duplex Steam Pump PDFDokumen3 halaman1017 Daa Aa Aa Duplex Steam Pump PDFBelesica Victor ValentinBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Bantubani ElectrodetechforbasemetalfurnacesDokumen10 halamanBantubani ElectrodetechforbasemetalfurnacesSEETHARAMA MURTHYBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- International Air Service Development at Boston Logan: June 7, 2012Dokumen20 halamanInternational Air Service Development at Boston Logan: June 7, 2012chaouch.najehBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Rate CardDokumen1 halamanRate CardSalvato HendraBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Revit Architecture ForumDokumen8 halamanRevit Architecture ForumI Gede Bayu Chandra NathaBelum ada peringkat

- Document 1Dokumen14 halamanDocument 1Lê Quyên VõBelum ada peringkat

- FloSet 80 ABVDokumen1 halamanFloSet 80 ABVHector TosarBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- KomatsuHydraulicBreaker8 29Dokumen22 halamanKomatsuHydraulicBreaker8 29Ke HalimunBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Data TP7CDokumen1 halamanData TP7CAkin Passuni CoriBelum ada peringkat

- Math G7 - Probability and StatisticsDokumen29 halamanMath G7 - Probability and StatisticsLeigh YahBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- ReportDokumen329 halamanReportHovik ManvelyanBelum ada peringkat

- Emision StandardsDokumen4 halamanEmision StandardsAshish RoongtaBelum ada peringkat

- The Problem: Best!'Dokumen4 halamanThe Problem: Best!'HospitilioBelum ada peringkat

- Automatic Temperature Controlled FanDokumen27 halamanAutomatic Temperature Controlled Fankannan100% (2)

- Strategic MGMT 4Dokumen33 halamanStrategic MGMT 4misbahaslam1986Belum ada peringkat

- Atheros Valkyrie BT Soc BriefDokumen2 halamanAtheros Valkyrie BT Soc BriefZimmy ZizakeBelum ada peringkat

- FULLTEXT01Dokumen14 halamanFULLTEXT01Văn Tuấn NguyễnBelum ada peringkat

- EE331 Lab 1 v2Dokumen13 halamanEE331 Lab 1 v2Áo ĐenBelum ada peringkat

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- AIS Romney 2006 Slides 18 Introduction To Systems DevelopmentDokumen153 halamanAIS Romney 2006 Slides 18 Introduction To Systems Developmentsharingnotes123Belum ada peringkat

- Daikin Ceiling Suspended Air ConditioningDokumen11 halamanDaikin Ceiling Suspended Air ConditioningWeb Design Samui100% (4)

- 9489 Enp Mexico Akal Ofa Rev1Dokumen47 halaman9489 Enp Mexico Akal Ofa Rev1Mijail David Felix Narvaez100% (1)

- Vibration Measuring Instrument: Assignment of Subject NVHDokumen28 halamanVibration Measuring Instrument: Assignment of Subject NVHSandeep Kadam60% (5)

- Liner Product Specification Sheet PDFDokumen1 halamanLiner Product Specification Sheet PDFsauravBelum ada peringkat

- Avista - Vegetation Management Frequently Asked QuestionsDokumen5 halamanAvista - Vegetation Management Frequently Asked QuestionslgaungBelum ada peringkat

- List of Portmanteau Words: GeneralDokumen7 halamanList of Portmanteau Words: GeneraltarzanBelum ada peringkat

- GTU BE- Vth SEMESTER Power Engineering ExamDokumen2 halamanGTU BE- Vth SEMESTER Power Engineering ExamBHARAT parmarBelum ada peringkat

- Problems - SPCDokumen11 halamanProblems - SPCAshish viswanath prakashBelum ada peringkat

- Apple's Iphone Launch A Case Study in Effective MarketingDokumen7 halamanApple's Iphone Launch A Case Study in Effective MarketingMiguel100% (1)

- CTM CTP Stepper Catalog en-EN 2007 PDFDokumen20 halamanCTM CTP Stepper Catalog en-EN 2007 PDFQUỐC Võ ĐìnhBelum ada peringkat

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)