386 Stamets

Diunggah oleh

Makarov ForovskyDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

386 Stamets

Diunggah oleh

Makarov ForovskyHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

4 Te Sun February zoo8

Going

Underground

u

n

c

u

v

:

)

.

v

:

:

:

o

:

:

February zoo8 Te Sun 5

Going

Underground

F

or several years people from dierent places and back-

grounds kept recommending the same oddly titled book

to me: Paul Stametss Mycelium Running: How Mush-

rooms Can Help Save the World (Ten Speed Press). Everyone

told me it was one of the most mind-bending texts theyd ever

read. With so many recommendations, I perversely hesitated

to pick the book up, and when I nally did, I prepared myself

to be disappointed.

I wasnt. Stamets fundamentally changed my view of nature

in particular, fungi: yeasts, mushrooms, molds, the whole lot

of them.

When we think of fungi, most of us picture mushrooms,

those slightly mysterious, potentially poisonous denizens of dark,

damp places. But a mushroom is just the fruit of the mycelium,

which is an underground network of rootlike bers that can

stretch for miles. Stamets calls mycelia the grand disassemblers

of nature because they break down complex substances into

simpler components. For example, some fungi can take apart

the hydrogen-carbon bonds that hold petroleum products to-

gether. Others have shown the potential to clean up nerve-gas

agents, dioxins, and plastics. Tey may even be skilled enough

to undo the ecological damage pollution has wrought.

Since reading Mycelium Running, Ive begun to consider

the possibility that mycelia know something we dont. Stamets

believes they have not just the ability to protect the environ-

ment but the intelligence to do so on purpose. His theory stems

in part from the fact that mycelia transmit information across

their huge networks using the same neurotransmitters that our

brains do: the chemicals that allow us to think. In fact, recent

discoveries suggest that humans are more closely related to

fungi than we are to plants.

Almost since life began on earth, mycelia have performed

important ecological roles: nourishing ecosystems, repairing

them, and sometimes even helping create them. Te fungis ex-

quisitely ne laments absorb nutrients from the soil and then

trade them with the roots of plants for some of the energy that

the plants produce through photosynthesis. No plant commu-

nity could exist without mycelia. Ive long been a resident and

defender of forests, but Stamets helped me understand that Ive

been misperceiving my home. I thought a forest was made up

entirely of trees, but now I know that the foundation lies below

ground, in the fungi.

Stamets became interested in biology in kindergarten, when

he planted a sunower seed in a paper cup and watched it sprout

and lift itself toward the light. Somewhere along the way, he de-

veloped a fascination with life forms that grow not toward the sun

but away from it. In the late seventies he got a Drug Enforcement

Administration permit to research hallucinogenic psilocybin

mushrooms at Evergreen State College in Washington. Stamets is

now fty-two and has studied mycelia for more than thirty years,

naming ve new species and authoring or co authoring six books,

including Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms (Ten

Speed Press) and Te Mushroom Cultivator (Agarikon Press).

Hes the founder and director of Fungi Perfecti (www.fungi.com),

a company based outside Olympia, Washington, that provides

mushroom research, information, classes, and spawn the

mushroom farmers equivalent of seed. Much of the companys

prots go to help protect endangered strains of fungi in the old-

growth forests of the Pacic Northwest. I interviewed Stamets

in June .

Jensen: How many different types of mushrooms are

there

Stamets: Tere are an estimated one to two million spe-

Paul Stamets On The Vast, Intelligent Network

Beneath Our Feet

ovvvic ivsv

6 Te Sun February zoo8

cies of fungi, of which about o,ooo

form mushrooms. A mushroom is

the fruit body the reproductive

structure of the mycelium, which is

the network of thin, cobweblike cells

that infuses all soil. Te spores in the

mushroom are somewhat analogous

to seeds. Because mushrooms are

eshy, succulent, fragrant, and rich

in nutrients, they attract animals

including humans who eat them

and thereby participate in spreading

the spores through their feces.

Our knowledge of fungi is far

exceeded by our ignorance. To date,

weve identied approximately ,ooo

of the o,ooo species of mushroom-

forming fungi estimated to exist,

which means that more than ,o per-

cent have not yet been identied. Fungi are essential for ecologi-

cal health, and losing any of these species would be like losing

rivets in an airplane. Flying squirrels and voles, for example,

are dependent upon trues, and in old-growth forests, the

main predator of ying squirrels and voles is the spotted owl.

Tis means that killing o trues would kill o ying squir-

rels and voles, which would kill o spotted owls.

Tats just one food chain that we can identify, there are

many thousands more we cannot. Biological systems are so

complex that they far exceed our cognitive abilities and our

linear logic. We are essentially children when it comes to our

understanding of the natural world.

Jensen: In your book you say that animals are more closely

related to fungi than they are to plants or protozoa or bacte-

ria.

Stamets: Yes. For example, we inhale oxygen and exhale

carbon dioxide, so do fungi. One of the big dierences between

animals and fungi is that animals have their stomachs on the

inside. About 6oo million years ago, the branch of fungi leading

to animals evolved to capture nutrients by surrounding their

food with cellular sacs essentially primitive stomachs. As

these organisms evolved, they developed outer layers of cells

skins, basically to prevent moisture loss and as a barrier

against infection. Teir stomachs were conned within the

skin. Tese were the earliest animals.

Mycelia took a dierent evolutionary path, going under-

ground and forming a network of interwoven chains of cells,

a vast food web upon which life ourished. Tese fungi paved

the way for plants and animals. Tey munched rocks, produc-

ing enzymes and acids that could pull out calcium, magnesium,

iron, and other minerals. In the process they converted rocks

into usable foods for other species. And they still do this, of

course.

Fungi are fundamental to life on earth. Tey are ancient,

they are widespread, and they have formed partnerships with

many other species. We know from the fossil record that evo-

lution on this planet has largely been steered by two cataclys-

mic asteroid impacts. Te rst was

ao million years ago. Te earth be-

came shrouded in dust. Sunlight was

cut o, and in the darkness, massive

plant communities died. More than

,o percent of species disappeared.

And fungi inherited the earth. Or-

ganisms that paired with fungi

through natural selection were re-

warded. Ten the skies cleared, and

light came back, and evolution con-

tinued on its course until 6 million

years ago, bam! It happened again.

We were hit by another asteroid, and

there were more massive extinctions.

Tats when the dinosaurs died out.

Again, organisms that paired with

fungi were rewarded. So these as-

teroid impacts steered life toward

symbiosis with fungi: not just plants and animals, but bacteria

and viruses, as well.

Jensen: Can you give some examples of these partner-

ships

Stamets: A familiar one is lichens, which are actually a

fungus and an alga growing symbiotically together. Another

is sleepy grass: Mesoamerican ranchers realized that when

their horses ate a certain type of grass, the horses basically got

stoned. When scientists studied sleepy grass, they found that it

wasnt the grass at all that was causing the horses to get stoned,

but an endophytic fungus, meaning one that grows within a

plant, in the stems and leaves.

Heres another example: At Yellowstones hot springs and

Lassen Volcanic Park, people noticed that some grasses could

survive contact with scalding hot water up to 6o degrees.

Scientists cultured these grasses in a laboratory and saw a

fungus growing on them. Tey thought it was a contaminant,

so they separated the fungus from the grass cells and tried

to regrow the grass. But without the fungus the grass died

at around o degrees. So they reintroduced this fungus and

regrew the grass, and once again it survived to 6o degrees.

Tat particular fungus, of the genus Curvularia, conveyed

heat tolerance to the grass. Scientists are now looking at the

possibility of getting this Curvularia to convey heat tolerance

to corn, rice, and wheat, so that these grasses could be grown

under drought conditions or in extremely arid environments,

expanding the grain-growing regions of the world.

Other researchers took a Curvularia fungus from cold

storage at a culture bank and joined it with tomatoes, expecting

that it would confer heat tolerance. But the tomatoes all died

at o degrees. Tey discovered that the cold storage had killed

a virus that wild Curvularia fungus carries within it which

was odd, since youd think cold storage would keep the virus

alive. When they reintroduced the virus back into the Curvu-

laria cultures and then reassociated the fungus with tomato

plants, the plants survived the heat. So this is a symbiosis of

three organisms: a plant, a fungus, and a virus. Only together

vui s:rv:s

February zoo8 Te Sun 7

could they survive extreme conditions.

Tese examples are just the tip of the iceberg. Tey show

the intelligence of nature, how these dierent entities form

partnerships to the benet of all.

Jensen: Of course this raises the question of boundaries:

Is that tomato-fungus-virus one entity or three Where does

one organism stop and the other begin

Stamets: Well, humans arent just one organism. We are

composites. Scientists label species as separate so we can com-

municate easily about the variety we see in nature. We need

to be able to look at a tree and say its a Douglas r and look

at a mammal and say its a harbor seal. But, indeed, I speak to

you as a unied composite of microbes. I guess you could say

I am the elected voice of a microbial community. Tis is the

way of life on our planet. It is all based on complex symbiotic

relationships.

A mycelial mat, which scientists think of as one entity,

can be thousands of acres in size. Te largest organism in the

world is a mycelial mat in eastern Oregon that covers a,aoo

acres and is more than two thousand years old. Its survival

strategy is somewhat mysterious. We have ve or six layers

of skin to protect us from infection, the mycelium has one

cell wall. How is it that this vast mycelial network, which is

surrounded by hundreds of millions of microbes all trying to

eat it, is protected by one cell wall I believe its because the

mycelium is in constant biochemical communication with its

ecosystem.

I think these mycelial mats are neurological networks.

Teyre sentient, theyre aware, and theyre highly evolved. Tey

have external stomachs, which produce enzymes and acids to

digest nutrients outside the mycelium, and then bring in those

compounds that it needs for nutrition. As you walk through a

forest, you break twigs underneath your feet, and the mycelium

surges upward to capture those newly available nutrients as

quickly as possible. I say they have lungs, because they are

inhaling oxygen and exhaling carbon dioxide, just like we are.

I say they are sentient, because they produce pharmacological

compounds which can activate receptor sites in our neurons

and also serotonin-like compounds, including psilocybin,

the hallucinogen found in some mushrooms. Tis speaks to

the fact that there is an evolutionary common denominator

between fungi and humans. We evolved from fungi. We took

an overground route. Te fungi took the route of producing

these underground networks that are highly resilient and

extremely adaptive: if you disturb a mycelial network, it just

regrows. It might even benet from the disturbance.

I have long proposed that mycelia are the earths natural

Internet. Ive gotten some ak for this, but recently scientists

in Great Britain have published papers about the architec-

ture of a mycelium how its organized. Tey focused on

the nodes of crossing, which are the branchings that allow the

mycelium, when there is a breakage or an infection, to choose

an alternate route and regrow. Teres no one specic point on

the network that can shut the whole operation down. Tese

nodes of crossing, those scientists found, conform to the same

mathematical optimization curves that computer scientists

have developed to optimize the Internet. Or, rather, I should

say that the Internet conforms to the same optimization curves

as the mycelium, since the mycelium came rst.

(end of excerpt)

u

n

c

u

v

:

)

.

v

:

:

:

o

:

:

A

mycelial mat, which scientists

think of as one entity, can be thou-

sands of acres in size. The largest organism

in the world is a mycelial mat in eastern

Oregon that covers 2,200 acres and is

more than two thousand years old.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Platelet Rich Plasma: Basic Science and Clinical ApplicationsDokumen35 halamanPlatelet Rich Plasma: Basic Science and Clinical ApplicationsAryan SharmaBelum ada peringkat

- EarthshipDokumen8 halamanEarthshipMakarov Forovsky100% (1)

- BiologyDokumen85 halamanBiologyAlways Legends100% (1)

- Macromolecules WorksheetDokumen6 halamanMacromolecules WorksheetMyka Zoldyck0% (1)

- Compost Tea Brewing ManualDokumen91 halamanCompost Tea Brewing ManualJanetS14338100% (1)

- Topical Test Biology Form 4Dokumen14 halamanTopical Test Biology Form 4Siti Wahida SuleimanBelum ada peringkat

- PLANTS REviewerDokumen3 halamanPLANTS REviewerJunie YeeBelum ada peringkat

- Genetics in AquacultureDokumen100 halamanGenetics in AquacultureDave DaveBelum ada peringkat

- Antioxidant Properties of Spices, Herbs and Other SourcesDokumen589 halamanAntioxidant Properties of Spices, Herbs and Other SourcesAna MariaBelum ada peringkat

- On Viktor S Grebennikov DiscoveriesDokumen2 halamanOn Viktor S Grebennikov DiscoveriesMakarov ForovskyBelum ada peringkat

- EMF Bioshield® Modulation Technologies of Pulsed Electro Magnetic RadiationDokumen2 halamanEMF Bioshield® Modulation Technologies of Pulsed Electro Magnetic RadiationMakarov ForovskyBelum ada peringkat

- Paul - Stamets - Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms-Color PhotosDokumen14 halamanPaul - Stamets - Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms-Color PhotosMakarov ForovskyBelum ada peringkat

- Piliostigma ThonningiiDokumen3 halamanPiliostigma ThonningiiMakarov ForovskyBelum ada peringkat

- Paul - Stamets - Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms-Color PhotosDokumen14 halamanPaul - Stamets - Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms-Color PhotosMakarov ForovskyBelum ada peringkat

- BioinformaticsDokumen167 halamanBioinformaticsGilbert MethewBelum ada peringkat

- Molecules Are DNA Molecules Formed by Laboratory Methods of Genetic RecombinationDokumen2 halamanMolecules Are DNA Molecules Formed by Laboratory Methods of Genetic RecombinationMarygrace Broñola100% (2)

- Biofertilizer For Crop Production and Soil Fertility: August 2018Dokumen9 halamanBiofertilizer For Crop Production and Soil Fertility: August 2018GnanakumarBelum ada peringkat

- Cell Modifications That Lead To AdaptationDokumen1 halamanCell Modifications That Lead To AdaptationJohn Barry Ibanez80% (15)

- EBMT 2021 ProgramDokumen288 halamanEBMT 2021 Programtirillas101Belum ada peringkat

- November 2006 MS - Paper 3 CIE Biology IGCSEDokumen6 halamanNovember 2006 MS - Paper 3 CIE Biology IGCSEUzair ZahidBelum ada peringkat

- Cell and Molecular Biology Lab ExperimentDokumen4 halamanCell and Molecular Biology Lab ExperimentMhel Rose BenitezBelum ada peringkat

- IMPORTANTVan de Ven and Poole (1995)Dokumen32 halamanIMPORTANTVan de Ven and Poole (1995)stefi1234Belum ada peringkat

- Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase PH20Dokumen1 halamanRecombinant Human Hyaluronidase PH20Iva ColterBelum ada peringkat

- Photosynthesis PDFDokumen22 halamanPhotosynthesis PDFbhaskar rayBelum ada peringkat

- 13 2 A Biotic Abiotic Keystone SpeciesDokumen12 halaman13 2 A Biotic Abiotic Keystone Speciesapi-235225555Belum ada peringkat

- 10 Biology EM 2023-24GDokumen257 halaman10 Biology EM 2023-24Gdishitagarwal22Belum ada peringkat

- About MangrovesDokumen5 halamanAbout MangrovesKathleen Laum CabanlitBelum ada peringkat

- Morphology of Cell Injury WordDokumen8 halamanMorphology of Cell Injury WordNCPP 2K18Belum ada peringkat

- Monteleone - Marx 2000 PRP Vs Thrombin in Skin Graft Donor Site RepairDokumen2 halamanMonteleone - Marx 2000 PRP Vs Thrombin in Skin Graft Donor Site RepairViviane KaramBelum ada peringkat

- Cell Structure and Function The Cel PDFDokumen6 halamanCell Structure and Function The Cel PDFEric VerunacBelum ada peringkat

- Godbout, J. P., & Glaser, R. (2006) - Stress-Induced Immune Dysregulation. Implications For Wound Healing, Infectious Disease and CancerDokumen7 halamanGodbout, J. P., & Glaser, R. (2006) - Stress-Induced Immune Dysregulation. Implications For Wound Healing, Infectious Disease and CancerFranco Paolo Maray-GhigliottoBelum ada peringkat

- Biology Practical Class 12Dokumen2 halamanBiology Practical Class 12ManishBelum ada peringkat

- Bio Test Gym 2a 2quarter 2022 BDokumen10 halamanBio Test Gym 2a 2quarter 2022 BJohny CashBelum ada peringkat

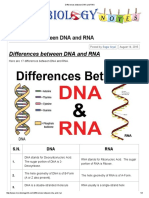

- Differences Between DNA and RNADokumen3 halamanDifferences Between DNA and RNAMeri SunderBelum ada peringkat

- Cognitive Power of WomenDokumen4 halamanCognitive Power of WomenEditor IJRITCCBelum ada peringkat

- Digestion and Absorption 111Dokumen6 halamanDigestion and Absorption 111Brijesh BalachandranBelum ada peringkat