Les Choses Changent - Marginalized Youth Rise Up!

Diunggah oleh

L.HowellJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Les Choses Changent - Marginalized Youth Rise Up!

Diunggah oleh

L.HowellHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Running Head: LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

Les choses changent: Marginalized Youth Rise up!

Lisa Howell The University of Ottawa

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP! Introduction

"Plus a change, plus c'est la meme chose." This pessimistic French expression is a common perspective among those who view the challenges that face marginalized youth as complex beyond comprehension. Surprisingly, the ideological perceptions of youth and the concept of "marginalized youth" are rather new phenomena, as prior to the Second World War, the idea of "youth" or "youth culture" was practically non-existent (Austin and Willard, 1998). The prosperity that occurred in post-war America increased buying power among youth and gave way to consumerism, style and identity and a youth culture formed. However, almost as soon as youth became part of the lexicon, so did the terms "delinquency," "resistance" and "problem youth." Rising from social changes such as the women's movement and the Vietnam War came a collective agency among youth that drove the anti-war movements and liberation sentiments of the 1960's and 1970's. Young people involved in social change were often seen as resisters, rather than activists; rebels rather than change-makers and problems rather than positive individuals. The majority was now confronted with the tenacious determination of youth with social capital. In this paper, I will argue that the notion, "Plus a change, plus c'est la meme chose" is ultimately convenient to the structures and policies that actually suppress opportunities for youth to build social capital and consequently contribute to the on-going complexities of youth poverty, crime, isolation, lack of education and suicide. The standard hegemony and social structures in education and the dogma of "change the youth" rather than "change the systems and structures" is in part what fuels the current states of marginalization among youth. In this paper, I will argue that while complex, the challenges facing marginalized youth are perpetuated by the rhetoric and discourse of mainstream systems, particularly in

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

education. In my research and experience, I find that the complexities that face marginalized youth do change, when the youth themselves initiate the changes and are supported by an open-minded, flexible and progressive community of mentors and advocates. As American writer Kurt Vonnegut once wrote: What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured. (as cited in Temple, 2012.) Theories of Social Capital The theoretical fathers of social capital, namely Putman, Coleman and Bourdieu, are often criticized for seeing children as passive recipients of parental social capital rather than active producers, which reflect the long-held "deficit model" of youth social capital (Holland, Reynolds & Weller, 2007, p. 97). Putman (2000) specifically emphasizes the importance of parental social capital and involvement on a child's development and educational achievements with little recognition of the child's own abilities to create and utilize social capital. However, studies such as the British "Locality, School and Social Capital Project" (Holland, Reynolds & Weller, 2007) show that youth do use their own social capital when making the transition from primary to secondary school. Siblings previously at the new school provided both bonding (emotional intimacy) and bridging (enabling friendships and providing "insider information"). As parental choice of schools expands, many youth are venturing beyond the boundaries of familiar communities and thus creating and utilizing "social capital in their everyday lives in order to negotiate important transitions and construct their identities" (Holland, Reynolds & Weller, 2007, p. 114). While it seems instinctual for young people to bond and bridge with peers to build social capital and cope with the pressures of teenage life, many of the policies and regulations in educational systems work to

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

keep them from doing just this. Rules are rampant in schools, as is the perspective that peer relationships are negative influences in educational attainment. Top-down policies that exclude "delinquent" students from collective activities such as sports teams work keep "delinquents" marginalized rather than allowing them access to opportunities that would allow bridging and bonding to take place as do No Tolerance" policies. Rather than working with youth proactively and changing structures within the system to better support them, many educational systems are reactive and disciplinary actions such as suspension provide a "one-size fits all" solution. These generic resolutions do exactly the opposite of what research on social capital in youth deem as necessary to building it: they consistently exclude and cast people to the margins, where "bonds and bridges" are distant prospects and "Plus a change, plus c'est la meme chose" is the dominant mantra. At-Risk Designation The linguistic discourse and societal interpretations of youth "at-risk" has contributed to widespread usage of the term in our collective lexicon. Though conceptualizing risk in this way has benefited some youth with access to useful services, an uncritical adoption of these terms can be harmful and "as with many educational ideologies may also have certain potential to reinforce the problems they seek to address or to produce new dangers" (Wotherspoon & Schissel, 2001, p. 321). Designating entire populations of students as "atrisk" situates culture, race, gender, sexual orientation, religion and socioeconomic status on the consciousness of educators rather than the individual. Students who come from "singleparent" households are deemed at-risk often before they step into the school, regardless of the family dynamic. First Nations, Inuit and Metis students are almost always viewed as "atrisk" and are often placed in remedial classes though they may be cognitively, artistically or

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

interpersonally advanced. It is these cases that magnify the truth: the "at-risk" designation is a socially constructed concept that often restricts youth, exacerbated by stereotypes, myths and perception. In several studies conducted in the UK on the topic of resiliency and resistance in young mothers, common themes among the women interviewed were the bonding and bridging that naturally transpires upon learning of their pregnancies and then birth of their children. McDermott's and Graham's 2005 article, "Resilient Young Mothering: Social Inequalities, Late Modernity and the 'problem of Teenage Motherhood" addresses the kin relations and social supports that illustrate young mothers resiliency and desire to bond and bridge: "With out the help of my Mum I don't think I would have coped. I lived at home until J (baby) was 18 months old." (Unnamed mother, as cited in McDermott & Graham, p. 72.) The stigmatization and demonizing particularity evident in these studies highlights that the risks related to young, single mothers are compounded by the social fabrications that create barriers and limitations, consequently impeding young mothers from gaining employment, education and freedom from the stigmatization as inappropriate mothers (Graham & Mc. Dermott, 2005, p. 69). These obstructions are incredibly difficult to change due to the deeply embedded mainstream values of the ideal mother, the morality of the nuclear family and ultimately the notion that young mothers fuel the growth of an underclass that encourages crime and delinquency (Graham & Mc. Dermott, 2005, p. 59). Women who choose to be both mother and father, and to raise their children without men fundamentally challenge the romanticized ideal of the family unit and threaten the comfortable status of the normative nuclear family. Ultimately, reality and common dogma cast them to both figurative and literal margins, as many are treated with judgment and hostility by the social housing authority: " Why do they put us here? They think we don't

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

matterjust cause we're young. They don't treat you like proper families, just bring us down here. No one wants to live down here." (as cited in McDermott & Graham, p. 69). Thus, Plus a change, plus c'est la meme chose." Young mothers continue to live in desperate poverty, despite their documented abilities to resist and survive. If the structures dont change, how can we possibly expect the situation to change? Structures and Policies in Education In many ways the commonplace notion that no matter what we change, there is no change is not surprise. Hegemony dictates reliance on the normative structures that support the status quo. Critical change to ways of thinking and being are far less safe though they are typically the impetus to lasting and meaningful transformation. Thus, implementing changes that agitate the dominant perception of youth as individuals without agency to those with agency is a tenacious task. Our hierarchal, typically gendered systems of government and education require youth to be kept in their place for the very survival of the status quo. When Friere first criticized the banking model of education he laid the foundation for critical pedagogy that has been largely relegated to the lecture rooms, debates and libraries of academia. Although Freires voice is widely recognized in educational and philosophical faculties, his notions of education as a critical consciousness to change the culture of silence (Maclure, class lecture, 2013) is still considered heterodox in many pedagogies, curriculums and policies that shape the treatment of and for youth. The inhumane treatment of Jeffery Buffalo and the denial to education by a school board in Ontario is completely counter to Freires insistence that dialogue involves respect, and should not involve one person acting on another, but rather people working with each other (Friere, 2000). Jeffery Buffalo, a First Nations student, was seen a subject to be controlled and managed rather

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

than an individual that deserved respectful dialogue and flexibility in a solutions based approach. Dialogue in itself is a co-operative activity involving respect. The process is so important (contrary to the isolation and marginalization that Jeffery endured) it can be seen as enhancing community, building social capital and to leading educators to act in ways that make for justice and human flourishing. Jeffery Buffalo and his family, like countless others on the voiceless margins, are clear examples of the need for a 'pedagogy of the oppressed' or a 'pedagogy of hope'. Freires work is only controversial as it demands a change from within; where hegemony is tossed aside for a critical view of our values, patterns of thinking and opportunities to question the status quo. Unlike the case of Jeffery Buffalo, the transformation at Pierre Elliott Trudeau School in Hull, Quebec has been just this: a critical view of the standard systems of structures when dealing with youth and a leap into the conscious world of change. Shifting the mindset from fix the kids to fix the system has allowed the school the liberty to modify simple procedural structures like recess to respond to the needs of the students. Community involvement, parental education, sports, arts and opportunities for social justice engagement has rehabilitated the school from an almost prison to an inclusive and joyful community. Things do change, when we look at the structures that are dictated by mindset. Youth Actions and Participation Rights."les choses changent" The people who are making the changes that are meaningful and lasting are the youth themselves. Agencies that are formed to support youth so often box them in. Youth that involve themselves in activism are changing the perception of the capabilities and futures of marginalized youth. The Idle No More movement sprung from individuals who could be

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

stereotypically classified as marginalized on three accounts: they were women, three out of four were aboriginal and they were advocating against mainstream ideology. Moreover, the young men who started walking to support the movement were also marginalized: teenaged, First Nations and from one of the most remote villages on Hudson Bay. Yet they walked over 1600 km through -50 degree Celsius temperatures with a vision of solidarity and strength. On their Journey of Nishyuu to Ottawa, they inspired over three hundred people to walk with them. When they arrived on Parliament Hill, after over two months of walking, aboriginal people from across Canada were there to celebrate them. Our Prime Minister was not; he had decided instead to greet the Panda Bears arriving in Toronto. Panda bears do not threaten the dominant governing policies with agency and social capital. Youth who walk from Hudsons Bay obviously hold power. Another incredible youth movement is Shannens Dream. Calling on the federal government to equalize education funding for students at schools on reserves, it is the largest youth driven movement in Canadian History. This Movement started when Shannen Koostachin, a Cree teenager from Attawapiskat, Ontario was forced to leave her community to go to secondary school. At 14 years old, she travelled to Ottawa and asked Chuck Strahl, then Minister of INAC, to build a new school in her community. When he refused, Shannen showed true leadership by continuing her fight for equality and by inspiring others to do the same. Shannen died in a horrific car accident on her way back to her community the day before her 16th birthday. Since this time, students across Canada have written letters, marched to Parliament, spoken at events and held meetings to work for change. The voices of the youth are undeniably strong and inherently understand issues of fairness, justice, equality and compassion, as children as young as seven years old have delivered speeches on the steps of Parliament. In February, my students won

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP!

a National Award from the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of Children for their work. What is it that encourages youth to stand up against the hegemony and assert their right to voice, power and expression? What bonds and bridges support the development of the social capital, resistance, resilience and agency that these youth possess? How can we even dare say that work with marginalized youth has not changed? How can we speak these words when all around us, marginalized youth, supported by adults who also question the authority of hegemonic culture, are rising, resisting and changing history as we speak? Conclusion The systems and policies that inform the work done with marginalized youth often work to oppress them rather than liberate them. From the very outset of youth culture came the discourse of problem, at-risk youth. In this essay I have argued that if things seem not to change, it is because the systems and structures are working to change the youth rather than change the ways the youth are treated. Interestingly, we see a movement of resistance and social activism rising from marginalized youth themselves. It is this movement itself that illustrates that the notion of at-risk youth and the stereotypes that exemplify the perspectives are truly a-risk to transformation. Real change will come when we remove the guise of hegemony and open our eyes to the agency of youth.

LES CHOSES CHANGENT: MARGINALIZED YOUTH RISE UP! References

10

Austin, Joe, and Michael Willard, eds. (1998). Generations of Youth: Youth Cultures and History in Twentieth-Century America. New York: New York University Press. Freire, Paulo. (2000) Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum Holland , J., Reynolds, T. and Weller, S. (2007) Transitions, networks and communities: The significance of social capital in the lives of children and young people, Journal of Youth Studies, 10 (1): 101-120. McDermott, E.; Graham, H. (2005). Resilient young mothering: social inequalities, late modernity and the 'problem' of 'teenage' motherhood. Journal of Youth Studies, Vol. 8, , p. 59-79. Putnam, Robert (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. Temple, Emily. (2012, November 11). The Greatest Life Advice from Kurt Vonnegut. (Web log comment). Retrieved from: http://flavorwire.com/345553/the-greatest-life-advicefrom-kurt-vonnegut/view-all. Wotherspoon, Terry and Bernard Schissel. (2001).The Business of Placing Canadian Children and Youth "At-Risk".Canadian Journal of Education.Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 321-339. Published by: Canadian Society for the Study of Education.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- How Can A Social Movement Feel So Meaningless? A Parent and Teacher's Reflections On "WE DAY"Dokumen9 halamanHow Can A Social Movement Feel So Meaningless? A Parent and Teacher's Reflections On "WE DAY"L.HowellBelum ada peringkat

- Queering Canada's Comfy Habitus: Decolonizing Our National Representations, Narratives and Pedagogy.Dokumen32 halamanQueering Canada's Comfy Habitus: Decolonizing Our National Representations, Narratives and Pedagogy.L.HowellBelum ada peringkat

- Commercialism and The Global Economy in SchoolsDokumen15 halamanCommercialism and The Global Economy in SchoolsL.HowellBelum ada peringkat

- Alfie Kohn Talk at The University of Regina March 2014Dokumen6 halamanAlfie Kohn Talk at The University of Regina March 2014L.HowellBelum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- BSF Lesson 6Dokumen14 halamanBSF Lesson 6nathaniel07Belum ada peringkat

- The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe News ReportDokumen2 halamanThe Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe News ReportCaitlin Y100% (1)

- Lectures 8 & 9: Protection of CreditorsDokumen36 halamanLectures 8 & 9: Protection of CreditorsYeung Ching TinBelum ada peringkat

- II B Veloso JR V CA 329 Phil 941 1996Dokumen4 halamanII B Veloso JR V CA 329 Phil 941 1996Kristell FerrerBelum ada peringkat

- Allan Nairn, "Our Man in FRAPH - Behind Haiti's Paramilitaries," The Nation, Oct 24, 1994Dokumen4 halamanAllan Nairn, "Our Man in FRAPH - Behind Haiti's Paramilitaries," The Nation, Oct 24, 1994DeclassifiedMatrix100% (1)

- PP vs. Gabrino - Ruling - LawphilDokumen5 halamanPP vs. Gabrino - Ruling - LawphillalaBelum ada peringkat

- The First American Among The Riffi': Paul Scott Mowrer's October 1924 Interview With Abd-el-KrimDokumen24 halamanThe First American Among The Riffi': Paul Scott Mowrer's October 1924 Interview With Abd-el-Krimrabia boujibarBelum ada peringkat

- IL#107000234686 - SIRN-003 - Rev 00Dokumen1 halamanIL#107000234686 - SIRN-003 - Rev 00Avinash PatilBelum ada peringkat

- Motion To ReconsiderDokumen5 halamanMotion To ReconsiderEhlers AngelaBelum ada peringkat

- ArleneDokumen7 halamanArleneGabriel Melchor PerezBelum ada peringkat

- Nature of Contracts ExplainedDokumen2 halamanNature of Contracts ExplainedDidin Eduave Melecio100% (1)

- Modern Indian History Montagu Chelmsford ReformsDokumen46 halamanModern Indian History Montagu Chelmsford ReformsManish PandeyBelum ada peringkat

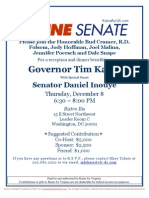

- Reception and DinnerDokumen2 halamanReception and DinnerSunlight FoundationBelum ada peringkat

- TEST 1 - LISTENING - IELTS Cambridge 9 (1-192)Dokumen66 halamanTEST 1 - LISTENING - IELTS Cambridge 9 (1-192)HiếuBelum ada peringkat

- Araw ng Kasambahay rights and obligationsDokumen3 halamanAraw ng Kasambahay rights and obligationsKara Russanne Dawang Alawas100% (1)

- Screenshot 2023-05-24 at 22.30.52Dokumen1 halamanScreenshot 2023-05-24 at 22.30.52Aston GrantBelum ada peringkat

- Middle School Junior High Band Recommended Winter Concert LiteratureDokumen5 halamanMiddle School Junior High Band Recommended Winter Concert LiteratureJoshua SanchezBelum ada peringkat

- DPCDokumen38 halamanDPCHarmanSinghBelum ada peringkat

- Esseye Medhin - 2002 - Addis Ababa Art Scene RevisitedDokumen10 halamanEsseye Medhin - 2002 - Addis Ababa Art Scene RevisitedBirukyeBelum ada peringkat

- Interpol Alert AssangeDokumen3 halamanInterpol Alert AssangeakosistellaBelum ada peringkat

- BPI V Far East MolassesDokumen4 halamanBPI V Far East MolassesYodh Jamin OngBelum ada peringkat

- Fishing Vessel Factory Trawler 1288Dokumen1 halamanFishing Vessel Factory Trawler 1288Ramon Velasco StollBelum ada peringkat

- Qualified Theft and Estafa JurisprudenceDokumen3 halamanQualified Theft and Estafa JurisprudenceGabriel Jhick SaliwanBelum ada peringkat

- Gen. Ins & Surety Corp. vs. Republic, 7 SCRA 4Dokumen7 halamanGen. Ins & Surety Corp. vs. Republic, 7 SCRA 4MariaFaithFloresFelisartaBelum ada peringkat

- FIFA World Cup Milestones, Facts & FiguresDokumen25 halamanFIFA World Cup Milestones, Facts & FiguresAleks VBelum ada peringkat

- 0 Unhealthy Relationships Rev 081706 GottmanDokumen19 halaman0 Unhealthy Relationships Rev 081706 GottmanDeepika Ghanshyani100% (7)

- Outlaw King' Review: Bloody Medieval Times and GutsDokumen3 halamanOutlaw King' Review: Bloody Medieval Times and GutsPaula AlvarezBelum ada peringkat

- Preagido v. SandiganbayanDokumen17 halamanPreagido v. SandiganbayanJohn FerarenBelum ada peringkat

- NAVSEA SW010-AD-GTP-010 TM Small Arms Special Warfare AmmunitionDokumen376 halamanNAVSEA SW010-AD-GTP-010 TM Small Arms Special Warfare Ammunitionsergey62Belum ada peringkat

- Delphia Yacht Model d40 PDFDokumen10 halamanDelphia Yacht Model d40 PDFBf IpanemaBelum ada peringkat