Office of The Ombudsman V

Diunggah oleh

Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Office of The Ombudsman V

Diunggah oleh

Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

OFFICE OF THE OMBUDSMAN v.

COURT

OF APPEALS and

DR. MERCEDITA J. MACABULOS

G.R. No. 159395, 07 May 2008,

The use of the word may is ordinarily

construed as permissive or directory, indicating

that a matter of discretion is involved.

Dr. Minda Virtudes (Dr. Virtudes) charged Dr.

Mercedita J. Macabulos (Dr. Macabulos) who

was then holding the position of Medical Officer

V at the Department of Education, Culture and

Sports National Capital Region (DECSNCR) or the Chief of the School Health and

Nutrition Unit with dishonesty, grave

misconduct, oppression, conduct grossly

prejudicial to the best interest of the service and

acts unbecoming a public official in violation of

the Civil Service Laws and the Code of Conduct

and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and

Employees. Dr. Virtudes alleged that Dr.

Macabulos incurred a cash advance of P45,000

and she was required by the latter to produce

dental and medical receipts for the liquidation of

the cash advance. Taking into account that Dr.

Virtudes was not yet assigned at School Health

and Nutrition Unit, DECS-NCR, she did not

submit the receipts and invoices.

Upon failure to submit the receipts, Dr.

Macabulos allegedly subjected her to several

forms of harassment. Dr. Macabulos denied the

accusations and claimed that it was Dr. Antonia

Lopez-Dee (Dr. Dee), the Supervising Dentist,

who used the money to purchase medical and

dental supplies. In support of her claim, she

attached an unnotarized affidavit of Dr. Dee

admitting said purchase using the cash advance

of Dr. Macabulos. Dr. Virtudes asserted that it

was Dr. Macabulos who used the cash advance

by improperly spending it and that she tried to

liquidate the same by submitting a tampered

invoice in conformity with the amount of the

cash advance. Graft Investigation Officer I

Ulysis S. Calumpad rendered a decision

absolving

Dr.

Macabulos

from

the

administrative charge. However, Overall Deputy

Ombudsman Margarito P. Gervacio, Jr.

disapproved the decision. He found out that Dr.

Dee signed an unnotarized affidavit but the

contents of the first page were entirely different

from the affidavit submitted by Dr. Macabulos

in her counter- affidavit. A new memorandum

by the Ombudsman was released finding Dr.

Macabulos guilty imposing upon her the penalty

of dismissal from the government service.

Thereafter, Dr. Macabulos filed a motion for

consideration before the Court of Appeals (CA).

The CA reversed the decision of the

Ombudsman ratiocinating that the Ombudsman

can no longer investigate the complaint since the

acts complained of were committed one year

from the filing of the complaint and that the

penalty imposed by the Ombudsman is not

immediately executory.

ISSUES:

1) Whether or not CAs interpretation of Section

20(5) of Republic Act No. 6670 (The Political

Law Ombudsman Act of 1989) as a prescriptive

period on the Ombudsman administrative

disciplinary cases is correct

2) Whether or not the penalty of dismissal from

the service meted on the private respondent is

immediately executory in accordance with the

valid rule of execution pending appeal uniformly

observed in administrative disciplinary cases

HELD: The Court of Appeals should have

granted the motion for intervention filed by the

Ombudsman. In its decision, the appellate court

not only reversed the order of the Ombudsman

but also delved into the investigatory power of

the Ombudsman. Since the Ombudsman was not

impleaded as a party when the case was

appealed to the Court of Appeals in accordance

with Section 6, Rule 43 of the Rules of Court,

the Ombudsman had no other recourse but to

move for intervention and reconsideration of the

decision in order to prevent the undue restriction

of its constitutionally mandated investigatory

power. The Court of Appeals held that under

Section 20(5) of R.A.6770, the Ombudsman is

already

barred

by

prescription

from

investigating the complaint since it was filed

more than one year from the occurrence of the

complained act. The Court found this

interpretation by the appellate court unduly

restrictive of the duty of the Ombudsman as

provided under the Constitution to investigate on

its own, or on complaint by any person, any act

or omission of any public official or employee,

office or agency, when such act or omission

appears to be illegal, unjust, improper, or

inefficient.

or failure by any officer without just cause to

comply with an order of the Office of the

Ombudsman to remove, suspend, demote, fine,

or censure shall be ground for disciplinary

action against said officer.

The use of the word may is ordinarily

construed as permissive or directory, indicating

that a matter of discretion is involved. Thus, the

word may, when used in a statute, does not

generally suggest compulsion. The use of the

word may in Section 20(5) of R.A. 6770

indicates that it is within the discretion of the

Ombudsman

whether

to

conduct

an

investigation when a complaint is filed after one

year from the occurrence of the complained act

or omission.

Hence, in the case of In the Matter to Declare in

Contempt of Court Hon. Simeon A.

Datumanong, Secretary of DPWH, the Court

noted that Section 7 of A.O. 17 provides for

execution of the decisions pending appeal,

which provision is similar to Section 47 of the

Uniform Rules on Administrative Cases in the

Civil Service.

The Court of Appeals held that the order of the

Ombudsman imposing the penalty of dismissal

is not immediately executory. The Court of

Appeals applied the ruling in Lapid v. Court of

Appeals, that all other decisions of the

Ombudsman which impose penalties that are not

enumerated in Section 27 of RA 6770 are

neither final nor immediately executory. In all

administrative disciplinary cases, orders,

directives, or decisions of the Office of the

Ombudsman may be appealed to the Supreme

Court by filing a petition for certiorari within ten

(10) days from receipt of the written notice of

the order, directive or decision or denial of the

motion for reconsideration in accordance with

Rule 45 of the Rules of Court.

The above rules may be amended or modified by

the Office of the Ombudsman as the interest of

justice may require. An appeal shall not stop the

decision from being executory. In case the

penalty is suspension or removal and the

respondent wins such appeal, he shall be

considered as having been under preventive

suspension and shall be paid the salary and such

other emoluments that he did not receive by

reason of the suspension or removal.

A decision of the Office of the Ombudsman in

administrative cases shall be executed as a

matter of course. The Office of the Ombudsman

shall ensure that the decision shall be strictly

enforced and properly implemented. The refusal

More recently, in the 2007 case of Buencamino

v. Court of Appeals, the primary issue was

whether the decision of the Ombudsman

suspending petitioner therein from office for six

months without pay was immediately executory

even pending appeal in the Court of Appeals.

The Court held that the pertinent ruling in Lapid

v. Court of Appeals has already been superseded

by the case of In the Matter to Declare in

Contempt of Court Hon. Simeon A.

Datumanong, Secretary of DPWH, which

clearly held that decisions of the Ombudsman

are immediately executory even pending appeal.

The petition is meritorious.

Intrinsic Aids

Where the meaning of a statue is

ambiguous, the court is warranted in

availing itself of all illegitimate aids to

construction in order that it can ascertain

the true intent of the statute.

The aids to construction are those found

in the printed page of the statute itself;

know as the intrinsic aids, and those

extraneous facts and circumstances

outside the printed page, called extrinsic

aids.

Title

It is used as an aid, in case of doubt in

its language to its construction and to

ascertaining legislative will.

If the meaning of the statute is obscure,

courts may resort to the title to clear the

obscurity.

The title may indicate the legislative

intent to extend or restrict the scope of

law, and a statute couched in a language

of doubtful import will be constructed to

conform to the legislative intent as

disclosed in its title.

Resorted as an aid where there is doubt

as to the meaning of the law or as to the

intention of the legislature in enacting it,

and not otherwise.

Serve as a guide to ascertaining

legislative intent carries more weight in

this jurisdiction because of the

constitutional requirement that every

bill shall embrace only one subject who

shall be expressed in the title thereof.

The constitutional injunction makes the

title an indispensable part of a statute.

The limit and purpose of the Legislature in

adopting Act No. 2874 was and is to limit its

application to lands of public domain and that

lands held in private ownership are not included

therein and are not affected in any manner

whatsoever thereby. Jones Law of 1916: That

no bill may be enacted into law shall embrace

more than one subject, and that subject shall be

expressed in the title of the bill.

Preamble

Central Capiz v. Ramirez

G.R. No. L-16197 (March 12, 1920)

FACTS:

Private Respondent contracted with Petitioner

Corporation for a term of 30 years, a supply of

all sugar cane produced on her plantation, which

was to be converted later into a right in rem and

recorded in the Registry of Property as an

encumbrance upon the land, and binding to all

future owners of the same. The Respondent

refuses to push through with the contract

thinking it might violate Act No. 2874, An Act

to amend and compile the laws relating to lands

of public domain, and for other purposes, since

more than 61 percent of the capital stock of the

corporation is held and owned by persons who

are not citizens of the Philippine Islands or of

the United States. The land involved is a private

agricultural land.

ISSUE:

W/N said Act no. 2874 is applicable to

agricultural lands, in the Philippine Islands

which are privately owned.

HELD:

It is a part of the statute written

immediately after its title, which states

the purpose, reason for the enactment of

the law.

Usually express in whereas clauses.

Generally omitted in statutes passed by:

Phil. Commission

Phil. Legislature

National Assembly

Congress of the Phil

Batasang Pambansa

These legislative bodies used the

explanatory note to explain the reasons

for the enactment of statutes.

Extensively used if Presidential decrees

issued by the President in the exercise of

his legislative power.

When the meaning of a statute is clear

and unambiguous, the preamble can

neither expand nor restrict its operation,

much less prevail over its text. Nor can

be used as basis for giving a statute a

meaning.

When the statute is ambiguous, the

preamble can be resorted to clarify the

ambiguity.

Preamble is the key of the statute, to

open the minds of the lawmakers as to

the purpose is achieved, the mischief to

be remedied, and the object to be

accomplished, by the provisions of the

legislature.

May decide the proper construction to

be given to the statute.

May restrict to what otherwise appears

to be a broad scope of law.

It may express the legislative intent to

make the law apply retroactively in

which case the law has to be given

retroactive effect.

People v. Purisima

A person was charged w/ violation of

PD 9 which penalizes, among others, the

carrying outside of ones residence any

bladed, blunt or pointed weapon not

used as a necessary tool or implement

for livelihood, with imprisonment

ranging from five to ten years.

Question rose whether the carrying of

such weapon should be in relation to

subversion, rebellion, insurrection,

lawless violence, criminality, chaos or

public disorder as a necessary element

of the crime.

The mere carrying of such weapon

outside ones residence is sufficient to

constitute a violation of the law

Pursuant to the preamble which spelled

out the events that led to the enactment

of the decree the clear intent and spirit

of the decree is to require the motivation

mentioned in the preamble as in

indispensable element of the crime.

The severity of the penalty for the

violation of the decree suggests that it is

a serious offense, which may only be

justified by associating the carrying out

of such bladed of blunt weapon with any

of the purposes stated in its preamble.

People of the Philippines v. Purisima

G.R. Nos. L-42050-66 (November 20, 1978)

FACTS:

Twenty-six petitions for review were filed

charging the respective Defendant with illegal

possession of deadly weapon in violation of

Presidential Decree No. 9. An order quashed the

information because it did not allege facts which

constitute the offense penalized by P.D. No. 9. It

failed to state one essential element of the crime,

viz.: that the carrying outside of the residence of

the accused of a bladed, pointed, or blunt

weapon is in furtherance or on the occasion of,

connected with or related to subversion,

insurrection, or rebellion, organized lawlessness

or public disorder. Petitioners argued that a

perusal of P.D. No. 9 shows that the prohibited

acts need not be related to subversive activities

and that they are essentially malum prohibitum

penalized for reasons of public policy.

ISSUE:

W/N P.D. No. 9 shows that the prohibited acts

need not be related to subversive activities.

HELD:

The primary rule in the construction and

interpretation of a legislative measure is to

search for and determine the intent and spirit of

the law. Legislative intent is the controlling

factor. Because of the problem of determining

what acts fall under P.D. 9, it becomes necessary

to inquire into the intent and spirit of the decree

and this can be found among others in the

preamble or whereas clauses which enumerate

the facts or events which justify the

promulgation of the decree and the stiff

sanctions stated therein.

Punctuation marks

Semi- colon used to indicate a

separation in the relation of the thought,

what follows must have a relation to the

same matter it precedes it.

Comma and semi- colon are use for the

same purpose to divide sentences, but

the semi colon makes the division a

little more pronounce. Both are not used

to introduce a new idea.

Punctuation marks are aids of low

degree and can never control against the

intelligible meaning of written words.

An ambiguity of a statute which may be

partially or wholly solved by a

punctuation mark may be considered in

the construction of a statute.

The qualifying effect of a word or

phrase may be confined to its last

antecedent if the latter is separated by a

comma from the other antecedents.

An argument based on punctuation is

not persuasive.

Case No. 203

G.R. No. L-22945 (March 3, 1925)

US. v. Hart

G.R. No. L-8327 (March 28, 1913)

FACTS:

Respondent was caught in a gambling house and

was penalized under Act No. 519 which

punishes every person found loitering about

saloons or dram shops or gambling houses, or

tramping or straying through the country without

visible means of support. The said portion of

the law is divided into two parts, separated by

the comma, separating those caught in gambling

houses and those straying through the country

without means of support. Though it was proven

that Hart and the other Defendants had visible

means of support, it was under the first part of

the portion of law for which they were charged

with. The prosecution persisted that the phrase

without visible means of support was in

connection to the second part of the said portion

of Act No. 519, therefore was not a viable

defense.

ISSUE:

How should the provision be interpreted?

HELD:

The construction of a statute should be based

upon something more substantial than mere

punctuation. If the punctuation gives it a

meaning which is reasonable and is in apparent

accord with legislative will, it may be as an

additional argument for adopting the literal

meaning of the words in the statute as thus

punctuated. An argument based on punctuations

alone is not conclusive and the court will not

hesitate to change the punctuation when

necessary to give the act the effect intended by

the legislature, disregarding superfluous and

incorrect punctuation marks, or inserting others

when necessary. Inasmuch as defendant had,

visible means of support and that the absence

of such was necessary for the conviction for

gambling and loitering in saloons and gambling

houses, defendants are acquitted.

FACTS:

Defendant appeals the ruling of the trial court

finding her guilty for the violation of illegal

practice of medicine and illegally advertising

oneself as a doctor. Defendant practices

chiropractic although she has not secured a

certificate to practice medicine. She treated and

manipulated the head and body of Regino

Noble. She also contends that practice of

chiropractic has nothing to do with medicine and

that unauthorized use of title of doctor should

be understood to refer to doctor of medicine

and not to doctors of chiropractic, and lastly,

that Act 3111 is unconstitutional as it does not

express its subject.

ISSUE:

W/N chiropractic is included in the term

practice of medicine under Medical laws

provided in the Revised Administrative Code.

HELD:

Act 3111 is constitutional as the title An Act to

Amend (enumeration of sections to be

amended) is sufficient and it need not include

the subject matter of each section. Chiropractic

is included in the practice of medicine.

Statutory definition prevails over ordinary usage

of the term. The constitutional requirement as

to the title of the bill must be liberally construed.

It should not be technically or narrowly

construed as to impede the power of legislation.

When there is doubt as to its validity, it must be

resolved against the doubt and in favor of its

validity. A bill shall embrace only one subject,

expressed in its title, to prohibit duplicity in

legislation by apprising legislators and the

public about the nature, scope, and

consequences of the law.

Capitalization of letters

An aid of low degree in the construction

of statute.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- United States v. JonesDokumen34 halamanUnited States v. JonesDoug MataconisBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Republic of The Philippines Vs Hon Caguioa G.R. 174385Dokumen7 halamanRepublic of The Philippines Vs Hon Caguioa G.R. 174385Dino Bernard LapitanBelum ada peringkat

- Angeles City Vs Angeles DigestDokumen1 halamanAngeles City Vs Angeles DigestNormzWabanBelum ada peringkat

- Offer LetterDokumen2 halamanOffer LetterIpe ClosaBelum ada peringkat

- Pecson V MediavilloDokumen4 halamanPecson V MediavilloHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Case DigestDokumen3 halamanCase DigestTeacherEli33% (3)

- Revised Implementing Rules & Regulations - RA 9184Dokumen77 halamanRevised Implementing Rules & Regulations - RA 9184profmlocampo100% (1)

- Homestead Patent and Free PatentDokumen2 halamanHomestead Patent and Free PatentHiezll Wynn R. Rivera67% (3)

- .NEC V JCTDokumen25 halaman.NEC V JCTAhamed Ziyath100% (1)

- Module 7Dokumen5 halamanModule 7Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- DotesDokumen3 halamanDotesHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Labor Er-Ee - LaridaDokumen14 halamanLabor Er-Ee - LaridaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Labor Er-Ee - LaridaDokumen14 halamanLabor Er-Ee - LaridaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- A DadadaDokumen1 halamanA DadadaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Parties and Case No. Controversy or Issue Does NLRC Have Jurisdiction? Reason What Happened To The CaseDokumen4 halamanParties and Case No. Controversy or Issue Does NLRC Have Jurisdiction? Reason What Happened To The CaseHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Republic of The PhilippinesDokumen5 halamanRepublic of The PhilippinesHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- 321Dokumen1 halaman321Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- EvidenceDokumen5 halamanEvidenceHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Affidavit of Vehicular Accident 2.0Dokumen2 halamanAffidavit of Vehicular Accident 2.0Dee ObriqueBelum ada peringkat

- Polytechnic University of The Philippines College of Accountancy and Finance Sta. Mesa, ManilaDokumen2 halamanPolytechnic University of The Philippines College of Accountancy and Finance Sta. Mesa, ManilaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Documents - MX People Vs YatcoDokumen3 halamanDocuments - MX People Vs YatcoHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- AMDokumen1 halamanAMHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Westwind Vs UcpbDokumen5 halamanWestwind Vs UcpbHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Aaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaDokumen1 halamanAaaaa AaaaaaaaaaaaaaaHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- ElccccsDokumen4 halamanElccccsHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- 1Dokumen2 halaman1Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Labor Law 2Dokumen41 halamanLabor Law 2Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Sanmigcorp Vs NLRCDokumen2 halamanSanmigcorp Vs NLRCHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- BP 129Dokumen7 halamanBP 129Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Westwind Vs UcpbDokumen5 halamanWestwind Vs UcpbHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Decision: Riley v. CaliforniaDokumen38 halamanDecision: Riley v. CaliforniacraignewmanBelum ada peringkat

- RIVERA, Hiezll Wynn R. Common Carrier Defenses Limitation of Liability (2001)Dokumen1 halamanRIVERA, Hiezll Wynn R. Common Carrier Defenses Limitation of Liability (2001)Hiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Certificate of Attendance: AdministrationDokumen1 halamanCertificate of Attendance: AdministrationHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- "Strict Nature Reserve" Is An Area Possessing Some Outstanding EcosystemDokumen1 halaman"Strict Nature Reserve" Is An Area Possessing Some Outstanding EcosystemHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- SMC Vs NLRCDokumen1 halamanSMC Vs NLRCHiezll Wynn R. RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- Torts Midterm ReviewerDokumen40 halamanTorts Midterm ReviewerpaultimoteoBelum ada peringkat

- Highway Speed Checker DisplayDokumen44 halamanHighway Speed Checker DisplayMahesh Kumar Vaish45% (11)

- Constable Market Definition FactorsDokumen5 halamanConstable Market Definition Factorssyahidah_putri88Belum ada peringkat

- Condillac, Essay On The Origin of Human KnowledgeDokumen409 halamanCondillac, Essay On The Origin of Human Knowledgedartgunn3445Belum ada peringkat

- Spouses Sy v. China Banking Corp.Dokumen14 halamanSpouses Sy v. China Banking Corp.LesterBelum ada peringkat

- Is-.14959.1-.2001 Determination Water Soluble Acid ChlorideDokumen12 halamanIs-.14959.1-.2001 Determination Water Soluble Acid ChlorideThomas MartinBelum ada peringkat

- Experienced Legal Intern Seeks New OpportunityDokumen1 halamanExperienced Legal Intern Seeks New OpportunitySambhav JainBelum ada peringkat

- Slogan Making ContestDokumen2 halamanSlogan Making ContestJon VaderBelum ada peringkat

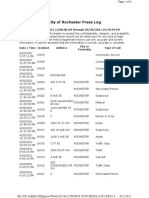

- RPD Daily Incident Report 4/20/21Dokumen6 halamanRPD Daily Incident Report 4/20/21inforumdocsBelum ada peringkat

- Judicial Notice of Ocwen Financial Charges of ForgeryDokumen174 halamanJudicial Notice of Ocwen Financial Charges of ForgeryChristopher Stoller EDBelum ada peringkat

- People V Soriano DigestDokumen4 halamanPeople V Soriano DigestAnit EmersonBelum ada peringkat

- Schematic For Proper Use of Illegal Booster PumpDokumen2 halamanSchematic For Proper Use of Illegal Booster PumpYusop B. MasdalBelum ada peringkat

- Forcible Entry and Unlawful Detainer: Rule 70Dokumen14 halamanForcible Entry and Unlawful Detainer: Rule 70Selene BrondialBelum ada peringkat

- Puteh Aman Power v Bittersweet Estates Mareva Injunction VariationDokumen12 halamanPuteh Aman Power v Bittersweet Estates Mareva Injunction VariationsyamilteeBelum ada peringkat

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondents de Jesus Paguio & Associates Atty. Alberto L. DeslateDokumen10 halamanPetitioners Vs Vs Respondents de Jesus Paguio & Associates Atty. Alberto L. DeslateFarrah Stephanie ReyesBelum ada peringkat

- UnpublishedDokumen21 halamanUnpublishedScribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Deemed Exports in GSTDokumen3 halamanDeemed Exports in GSTBharat JainBelum ada peringkat

- Judge's Abuse of Disabled Pro Per Results in Landmark Appeal: Disability in Bias California Courts - Disabled Litigant Sacramento County Superior Court - Judicial Council of California Chair Tani Cantil-Sakauye – Americans with Disabilities Act – ADA – California Supreme Court - California Rules of Court Rule 1.100 Requests for Accommodations by Persons with Disabilities – California Civil Code §51 Unruh Civil Rights Act – California Code of Judicial Ethics – Commission on Judicial Performance Victoria B. Henley Director – Bias-Prejudice Against Disabled Court UsersDokumen37 halamanJudge's Abuse of Disabled Pro Per Results in Landmark Appeal: Disability in Bias California Courts - Disabled Litigant Sacramento County Superior Court - Judicial Council of California Chair Tani Cantil-Sakauye – Americans with Disabilities Act – ADA – California Supreme Court - California Rules of Court Rule 1.100 Requests for Accommodations by Persons with Disabilities – California Civil Code §51 Unruh Civil Rights Act – California Code of Judicial Ethics – Commission on Judicial Performance Victoria B. Henley Director – Bias-Prejudice Against Disabled Court UsersCalifornia Judicial Branch News Service - Investigative Reporting Source Material & Story IdeasBelum ada peringkat

- Saint Mary Crusade To Alleviate Poverty of Brethren Foundation, Inc. vs. RielDokumen12 halamanSaint Mary Crusade To Alleviate Poverty of Brethren Foundation, Inc. vs. RielRaine VerdanBelum ada peringkat

- Astm e 11 - 1995Dokumen7 halamanAstm e 11 - 1995jaeyoungyoonBelum ada peringkat

- The Beginning of Law and The Adat RechtDokumen7 halamanThe Beginning of Law and The Adat RechtRizka Desriyalni0% (1)

- Obli DigestDokumen5 halamanObli DigestnellafayericoBelum ada peringkat

- Dwelly Cauley v. United States, 11th Cir. (2010)Dokumen5 halamanDwelly Cauley v. United States, 11th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsBelum ada peringkat

- Dennis A. B. Funa, Petitioner, vs. The Chairman, Coa, Reynaldo A. Villar G.R. No. 192791, April 24, 2012Dokumen24 halamanDennis A. B. Funa, Petitioner, vs. The Chairman, Coa, Reynaldo A. Villar G.R. No. 192791, April 24, 2012Yeshua TuraBelum ada peringkat

- 8366 2018 Judgement 13-Apr-2018Dokumen14 halaman8366 2018 Judgement 13-Apr-2018Disability Rights AllianceBelum ada peringkat