Posessed Women and Van de Port's "Really Real"

Diunggah oleh

haven000Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Posessed Women and Van de Port's "Really Real"

Diunggah oleh

haven000Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

April 29, 2013 Possessed Women and Van de Ports Really Real The majority of popular literature on possession

trance seems to focus on the prevalence of the occurrence among women rather than men. Scholars tend to agree that this commonality is due to womens conscious act of rebellion against their subordination. Other authors, however, believe that a stronger, unconscious attraction to ineffable entities entices individuals to reject the postmodern obsession with definitive knowledge and act in a manner that is outside themselvesa manner that Matijs Van de Port argues is really real. Among the articles I read, a common consensus was determined. While their symptoms may differ, all individuals share a susceptibility to possession; that is, possession, unlike any other psychological defense, is ideally suited to coping with their conflicts. Possession affords two positive advantages: escape from unpleasant reality, and diminution of guilt by projecting blame onto an intruding agent. (Beaubrun 206) Furthermore, popular literature asserts that the popularity of mediumship and spirit possession among women is due to this sexs heightened need for psychological defense. Janice Boddy exemplifies these needs in her article about spirit possession among the women of the Hofriyati village in Sudan. She explains that many of the Hofriyati women are diagnosed by their people group as being possessed by a spirit. The Hofriyati believe that after the spirits arrive, they will forever remain entrenched in the woman and require placation.

Boddy asserts that these women are especially susceptible to spirit infiltration because their sense of self has been over determined by their society. The women, she explains, are collectively indispensable to society while individually dispensable to men, because their primary role in society is to procreate (Boddy 401). If a woman is unable to procreate, her society blames her for her failures and allows her husband to take on a new wife. Boddy argues that the stress caused by this cultural expectation, as well as the stressors of other relational crises, cause the Horfriyati women to seek personhood outside of themselves. When the women become possessed by the spirits or zairan, they temporarily adopt a new set of moral discriminations and act in a manner that is not usually accepted by their society. Despite their amoral behavior, the possessed women do not have to take responsibility for their actions. Instead, they are given an opportunity to step outside their everyday world and gain perspective on their lives (Boddy 414). With this distanced perspective the Hofriyati women are empowered to escape their own version of reality. In Erika Bourguignons article Suffering and Healing, Subordination and Power, she submits more examples of individuals escaping their reality of suffering by becoming possessed. First, she describes a middle-aged Israeli woman who began to speak roughly and violently after her abusive husband died and left her to care for their eight children. In a second report, Bourguignon talks about a Russian teenager who began to behave strangely, atypically: she cursed, used obscene language and gestures, was sleepless, misbehaved, laughed wildly, and so forth, after witnessing the death of a motorcyclist, initiating a romantic relationship that

her parents disapproved of, and getting kicked out of school (569). Bourguignon uses these examples to suggest that women respond to and express their powerlessness with possession trance, and she furthers Boddys argument by suggesting that these cases illustrate a dissociation that Boddy and other authors fail to address. This dissociation is the defining factor between individuals who consciously enter into possession trance in an attempt to experience a discontinuity of self and those who unconsciously submit to the total identification with and submission to powerful others (Bourguignon 559). Bourguignon asserts that this second type of possession is important to consider when discussing the female reliance on possession-trance. Rather than adopt an acceptable, and consciously deniable, way to express unconscious forbidden thoughts and feelings, women who undergo a dissociated form of possession express no desire to bring about such possession and claim to be unable to remember what they experienced while under the possession trance (Bourguignon 558). This dissociation allows women to utilize what Bourguignon refers to as the ultimate indirection to conquer the reality of their subordination: When the spirits take over, women can do unconsciously what they do not permit themselves to do consciouslythey have ultimate deniability (Bourguignon 572). This ultimate deniability not only provides the possessed with an escape from subordination, but oftentimes it enhances a communitys overall perception of the possessed individual: In one sense, possessed individuals are accorded a sense of dignity and prestige in their subculture, and, even more importantly, they may be

given the affection and emotional support lacking in their daily lives. (Beaubrun 207). This dignity and prestige oftentimes attracts attention from many types of viewers, and according to Lucy Huskinson and Bettina E. Schmidt, the possession, regardless of the intent of the possessed, becomes a type performance. In their book, Spirit Possession and Trance, Huskinson and Schmidt explain that the word performance can be used to describe an organizing concept that includes a performers expectations, training, and personal narratives as well as the context in which the performance exists. In an attempt to learn more about what it is to perform possession and to be possessed in a performance, the books authors interview J. who is a professional medium and B. who is a professional actor (206). Through these interviews, the authors discovered a similarity between the ways that both J. and B. discussed their performances: the two described their best performances as ones in which they were able to channel another self. J. bemoaned the fact that she was rarely ever to empty herself enough to allow a spirit to take her into full trance, and B. lists her favorite performance as being one in which she was able to fully let go of her own self and take on the mindset and qualities of her character. Spirit Possession and Trance explains the other self that both J. and B. invite into their emptied being as one in a series of selves. First, there is a pedestrian self that performers must free themselves from to perform completely. Secondly, there is the other self that performers allow into their being in attempts to experience an authentic other reality. Thirdly, there is the technical self, which acts as a volume control between the pedestrian and other selves. This particular self

ensures that the pedestrian self does not get lost during performance and that the other self has room to fully manifest itself. Huskinson and Schmidt explain that in performance, performers ask the audience to suspend disbelief, at least for a time, in order to treat what they experience as being provisionally authentic., and it is due to the dance between these three types of selves that performers of any sort are able to treat their own experience as authentic (209). While performers of possession-trance and performers of theater are different in many ways, their similarities help to better explain the need for individuals to escape from pedestrian thinking so that they may adopt an other way of experiencing reality. All of these scholars focus their attention on an individuals escape from reality. They explain that women escape powerlessness, subordination and blame by consciously and, in other cases, unconsciously entering into a realm that is outside of their reality. Although these arguments are intriguing, the outside, escapist, and other type of language did nothing to quell my own personal queries about where and what these individuals are escaping in to. Anthropologist Matthijs Van de Port somewhat answers this question in his fascinating article Circling Around the Really Real. Van de Port first declares the ineffability of possession. He then proceeds to explore what use people make of occurrences that might be (or must be) labeled that way (152). Asserting a claim similar that of Boddys over- determination, Van de Port claims that in the postmodern world humanity is drenched in the overauthenticated (153). In this world of overflowing symbolism and the convenience of explanation, phenomena seem to be positioned beyond received ways of

knowing and understanding, and therefore, it is becoming increasingly attractive (153). Van de Port discusses this attraction in light of Lacanian thought, which suggests that symbolism has constructed us and constricted our possibility for holism. Lacanians argue that the realities that lie outside of our realm of signification are wholly Real and slip through humanitys web of signification when disaster strikes and signification is not powerful enough to describe the outcome. The Lacanians believed that this reality must be avoided at all costs. Van de Port argues that it is this Lacanian idea of Real that people seek through possession. He supports his hypothesis by describing a scene in which a traditional Candomble ceremony, one in which spirits descend upon worshippers and possess them, is used as a tourist attraction. Van de Port says that even though the ceremony has become commercialized, heightened and transformed from its truly authentic roots, the performance of the ceremony affects and intrigues audience members in the same way that an authentic Candomble dance would. Drawing from Jean Baudrillards research on simulacrae, Van de Port explains that although the performance is a mere replication of the authentic, the audiences desire to escape from reality and over-authentication causes them to enter into the mysteries of this ineffable Real: When people begin to mourn the loss of the self-evident nature of things, they likely develop a craving for authenticity, for encounters with something that is really real and somehow immune from the disturbing work of simulacrae (161). Because of the desires of postmodern humanity is trying to look

through signification as well as simulacrae, Van de Port suggests that the Lacanians avoidance of the Real might be a misguided fear. Although many other authors have already suggested that there is no arguing with something that is beyond comprehension, Van de Port casts this lack of comprehension as a positive entity (Van de Port 167). The ineffable is not a nameless place to which one escapes. While, yes, it is indefinable and largely unknowable, the ineffable is a place of the really Real. Van de Ports article fails to explain how this argument might encompass or relate to possession-trance cases that occurred before a postmodern age, but it still presents an interesting assessment of the land beyond subordination and powerlessness. If Van de Ports assessment is plausible, then humankind is in search of something greater than what it are capable of seeing and describing. Boddy and Bourguignon have shown that suffering people are more susceptible to escaping to or being overcome by an other self, and Huskinson and Schmidt have discovered a prevalent need for performers to empty and balance their varying senses of self. As suffering people become increasingly overwhelmed with symbols, ritual, and the simulation of the two, it is possible that they will be forced to enter into a reality that is more Real and less definable than what they currently experience. If the practice of entirely dissociating of self becomes more commonplace, people might begin to claim less and less responsibility for their actions, and possession-trance will become an even more frequent and widespread phenomenon.

Works Cited Beaubrun, Micahel, and Colleen A. Ward. The Psychodynamics of Demon Possession. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 19.2. 1980: 201-207. JSTOR. Web. 30 April 2013.

Boddy, Janice. Spirits and Selves in Northern Sudan: The Cultural Therapeutics of Possession and Trance. A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion. Ed. Michael Lambek. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2002. Bourguignon, Erika. Suffering and Healing, Subordination and Power: Women and Possession Trance. Ethos. 32.4. 2004: 557-574. JSTOR. Web. 30 April 2013. Huskinson, Lucy, and Bettina E. Schmidt. Spirit Possession and Trance: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. London: Continuum, 2010. Ebscohost.com. Web. 30 April 2013. 398-417. Print. Van de Port, Mattijs van de Port. Circling around the Really Real: Spirit Possession Ceremonies and the Search for Authenticity in Bahian Candomble. Ethos. 33.2. 2005: 149-179. JSTOR. Web. 30 April 2013.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- 2017 THE BLUE WAY Visual PDFDokumen54 halaman2017 THE BLUE WAY Visual PDFAlex KappelBelum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Post Traumatic Stress DisorderDokumen2 halamanPost Traumatic Stress Disorderapi-188978784100% (1)

- 45096Dokumen12 halaman45096Halusan MaybeBelum ada peringkat

- High CarbonDokumen2 halamanHigh CarbonKarisoBelum ada peringkat

- Api 579-2 - 4.4Dokumen22 halamanApi 579-2 - 4.4Robiansah Tri AchbarBelum ada peringkat

- 4th Summative Science 6Dokumen2 halaman4th Summative Science 6brian blase dumosdosBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Emergency ManagementDokumen8 halamanWhat Is Emergency ManagementHilina hailuBelum ada peringkat

- CH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisDokumen12 halamanCH 13 RNA and Protein SynthesisHannah50% (2)

- Cough PDFDokumen3 halamanCough PDFKASIA SyBelum ada peringkat

- Brachiocephalic TrunkDokumen3 halamanBrachiocephalic TrunkstephBelum ada peringkat

- W2 - Fundementals of SepDokumen36 halamanW2 - Fundementals of Sephairen jegerBelum ada peringkat

- 348 - Ct-Tol Toluene TdsDokumen1 halaman348 - Ct-Tol Toluene Tdsonejako12Belum ada peringkat

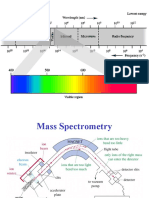

- Mass SpectrometryDokumen49 halamanMass SpectrometryUbaid ShabirBelum ada peringkat

- Manual Chiller Parafuso DaikinDokumen76 halamanManual Chiller Parafuso Daiking3qwsf100% (1)

- Earth As A PlanetDokumen60 halamanEarth As A PlanetR AmravatiwalaBelum ada peringkat

- Module 2: Environmental Science: EcosystemDokumen8 halamanModule 2: Environmental Science: EcosystemHanna Dia MalateBelum ada peringkat

- EDC MS5 In-Line Injection Pump: Issue 2Dokumen57 halamanEDC MS5 In-Line Injection Pump: Issue 2Musharraf KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Soal 2-3ADokumen5 halamanSoal 2-3Atrinanda ajiBelum ada peringkat

- HumareaderDokumen37 halamanHumareaderStefan JovanovicBelum ada peringkat

- SAT Subject Chemistry SummaryDokumen25 halamanSAT Subject Chemistry SummaryYoonho LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Athletes Who Made Amazing Comebacks After Career-Threatening InjuriesDokumen11 halamanAthletes Who Made Amazing Comebacks After Career-Threatening InjuriesანაBelum ada peringkat

- OpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSDokumen42 halamanOpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSAngelaBelum ada peringkat

- VOC & CO - EnglishDokumen50 halamanVOC & CO - EnglishAnandKumarPBelum ada peringkat

- Moderated Caucus Speech Samples For MUNDokumen2 halamanModerated Caucus Speech Samples For MUNihabBelum ada peringkat

- BRC1B52-62 FDY-F Ducted Operation Manual - OPMAN01!1!0Dokumen12 halamanBRC1B52-62 FDY-F Ducted Operation Manual - OPMAN01!1!0Justiniano Martel67% (3)

- Presentation of DR Rai On Sahasrara Day Medical SessionDokumen31 halamanPresentation of DR Rai On Sahasrara Day Medical SessionRahul TikkuBelum ada peringkat

- Capacitor BanksDokumen49 halamanCapacitor BanksAmal P RaviBelum ada peringkat

- Extraordinary GazetteDokumen10 halamanExtraordinary GazetteAdaderana OnlineBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding Senior Citizens Outlook of Death Sample FormatDokumen14 halamanUnderstanding Senior Citizens Outlook of Death Sample FormatThea QuibuyenBelum ada peringkat

- Creamy and Thick Mushroom Soup: IngredientsDokumen8 halamanCreamy and Thick Mushroom Soup: IngredientsSheila Mae AramanBelum ada peringkat