Modi Fied Blalock Taussig Shunt: A Not-So-Simple Palliative Procedure

Diunggah oleh

Jakler NicheleDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Modi Fied Blalock Taussig Shunt: A Not-So-Simple Palliative Procedure

Diunggah oleh

Jakler NicheleHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Modied Blalock Taussig shunt: a not-so-simple palliative procedure

Verena Dirks

a

, Ren Prtre

b

, Walter Knirsch

c,d

, Emanuela R. Valsangiacomo Buechel

c,d

, Burkhardt Seifert

e

,

Martin Schweiger

a,d

, Michael Hbler

a,d

and Hitendu Dave

a,d,

*

a

Division of Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery, University Childrens Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

b

Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, University Hospital Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

c

Department of Paediatric Cardiology, University Childrens Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

d

Childrens Research Centre, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

e

Division of Biostatistics, Institute for Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

* Corresponding author. Division of Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery, University Childrens Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. Fax: +41-44-2668021;

e-mail: hitendu.dave@kispi.uzh.ch; hitendu@hotmail.com (H. Dave).

Received 7 January 2013; received in revised form 26 February 2013; accepted 27 February 2013

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Thirty-two consecutive isolated modied Blalock Taussig (BT) shunts performed in infancy since 2004 were reviewed and

analysed to identify the risk factors for shunt intervention and mortality.

METHODS: Sternotomy was the only approach used. Median age and weight were 10.5 (range 174) days and 2.9 (1.94.4) kg, respect-

ively. Shunt palliation was performed for biventricular hearts (Tetralogy of Fallot/double outlet right ventricle/transposition of great

arteries_ventricular septal defect_pulmonary stenosis/pulmonary atresia_ventricular septal defect/others) in 21, and univentricular hearts

in 11, patients. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome patients were excluded. Two procedures required cardiopulmonary bypass. Median

shunt size was 3.5 (34) mm and median shunt size/kg body weight was 1.2 (0.91.7) mm/kg. Reduction in shunt size was necessary in

5 of 32 (16%) patients.

RESULTS: Three of 32 (9%) patients died after 3 (115) days due to cardiorespiratory decompensation. Lower body weight (P = 0.04)

and bigger shunt size/kg of body weight (P = 0.004) were signicant risk factors for mortality. Acute shunt thrombosis was observed in

3 of 32 (9%), none leading to death. Need for cardiac decongestive therapy was associated with univentricular hearts (P < 0.001), bigger

shunt size (P = 0.054) and longer hospital stay (P = 0.005). Twenty-eight patients have undergone a successful shunt takedown at a

median age of 5.5 (0.511.9) months, without late mortality.

CONCLUSIONS: Palliation with a modied BT shunt continues to be indicated despite increased thrust on primary corrective surgery.

Though seemingly simple, it is associated with signicant morbidity and mortality. Effective over-shunting and acute shunt thrombosis

are the lingering problems of shunt therapy.

Keywords: Modied Blalock Taussig shunt Palliation Mortality Cyanotic heart disease

INTRODUCTION

While the classic Blalock Taussig shunt was a breakthrough in

treating cyanotic heart diseases [1], it involves sacricing ante-

grade ow to the subclavian artery with its attendant risks [2, 3].

In 1975, de Leval modied the technique, using a polytetra-

uoroethylene interposition graft popularly known as the modi-

ed Blalock Taussig (BT) shunt (MBTS) [4]. While MBTS has

become an established palliative procedure with progressive

improvements in the outcome [5], growing experience has led to

increasing thrust on primary corrective procedures. Palliative

strategy has obvious disadvantages, such as the need for two

operations, potentially two scars, possibility of distortion of the

branch pulmonary artery, volume loading of the ventricles, lower

diastolic pressures, etc. In spite of these, primary shunt palliation

continues to be indicated in neonates with physiological pul-

monary hypertension, which makes a bidirectional Glenn shunt

untenable. Many centres also consider a primary neonatal cor-

rection of Tetralogy of Fallot to be riddled with risks and hence,

still prefer to palliate neonates in blue spells.

While acknowledging its role even in the modern era, mortal-

ity of the MBTS procedure is relatively high, tending to be

around 10% [6]. This report is based on 32 consecutive rst

time MBTS palliations performed at our institution since 2004,

with a view to analysing the risk factors for mortality, shunt

thrombosis and need for decongestive therapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Thirty-two MBTS procedures performed in neonates and infants

at our institution since 2004 were analysed. MBTS performed in

The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. All rights reserved.

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 44 (2013) 10961102 ORIGINAL ARTICLE

doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezt172 Advance Access publication 28 March 2013

patients with HLHS or as a part of other complex procedures,

such as unifocalization, were excluded. Twenty-six patients were

neonates and 6 were infants. Twenty-ve patients were male.

The demographic data are detailed in Table 1. Diagnosis was

established using trans-thoracic echocardiography.

End points

Primary end points were mortality and shunt thrombosis.

Secondary end points such as need for excessive inotropic

support and cardiac decongestive therapy were also analysed. A

brief analysis comparing Era 1 (200407) and 2 (200811) was

performed to see if the results had changed over time and to

identify the factors that may have accounted for that change.

Surgical technique

All MBTS procedures were performed through a sternotomy.

Two procedures required cardiopulmonary bypass. After full

sternotomy, the right lobe of the thymus was excised; the course

of the brachiocephalic trunk up to its bifurcation was dissected.

The right pulmonary artery up to the hilum was dissected.

A bolus of 100 IU/kg crystalline heparin was administered. The

brachiocephalic trunk was clamped with a Cooley clamp, and

the distal right subclavian artery, temporarily with a ligaclip.

A longitudinal arteriotomy was performed at the premarked

undersurface of the truncus to subclavian artery continuity. An

obliquely fashioned end of the thin-wall Gore-Tex stretch vascu-

lar graft (W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc., AZ, USA) was sutured

end-to-side to the arteriotomy. Clamps were released and good

shunt ow through the anastomosis ascertained. The Cooley

clamp was placed again to exclude the proximal anastomosis

from the circulation. The shunt length was trimmed so as to

avoid it being too long. The shunt lumen was ushed to remove

microthrombi. The right pulmonary artery was excluded from

circulation using two vascular clamps. The transversely fashioned

distal end of the graft was anastomosed to the right pulmonary

artery. The target arterial saturation was 7585% (Q

P

:Q

s

1).

Patent duct: to ligate or not?

Our preference was to ligate the persistent ductus arteriosus

(PDA) in all patients having forward ow through their main pul-

monary artery. In shunt-dependent circulations, the patent duct

was often circumvented and almost obliterated using a silastic

sling and ligaclips. The aim of this manoeuvre was to allow a

quick rescue by re-establishing ductal ow in case of a shunt

thrombosis emergency.

Selection of shunt size

As a rule of thumb, a 3-mm graft was used for children around

3 kg or lower in body weight, whereas a 3.5-mm graft was used

for children around 3.5 kg. The indication, whether palliating for

a univentricular or a biventricular heart, inuenced the size se-

lection in borderline weight-class children. Fine regulation of

ow and pressure was inuenced by displacing the proximal

inow anastomosis either to the proximal subclavian artery or to

the brachiocephalic trunk, as well as by slightly titrating the

length of the shunt. The details of shunt size and positioning are

summarized in Table 2.

Postoperative left open sternum

The primary goal was to close the chest at the shunt procedure.

However, if there were any fears about the fate of the shunt

(especially in totally shunt-dependent pulmonary circulation) or

about the shunt getting squeezed behind the aorta, etc. the

sternum was left open. It was believed that an open sternum

lends itself to a quick response in case of an emergency when

compared with a closed chest.

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation regimen was decided on a case-by-case basis.

Therapeutic heparinization was performed in high-risk shunt

scenarios, such as shunt-dependent pulmonary perfusion, in

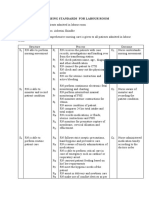

Table 1: Preoperative clinical characteristics

Variable Median (range)

N 32

Age (days) 10.5 (174)

Weight at operation (kg) 2.9 (1.94.4)

Size (cm) 48 (3952)

Body surface area (m) 0.2 (0.140.24)

SpO

2

(%) 85 (5095)

Diagnosis n (%)

TOF/DORV/TGA_VSD_PS, pulmonary

atresia_VSD, Ebsteins anomaly

21 (66)

Single ventricle inclusive of pulmonary

atresia_intact septum

11 (34)

TOF: Tetralogy of Fallot; DORV: double outlet right ventricle; TGA:

transposition of great arteries; VSD: ventricular septal defect; PS:

pulmonary stenosis.

Table 2: Shunt procedure details

Variable N (%) except otherwise

stated

No. of shunts (mm)

3 8 (25)

3.5 19 (59)

4 5 (16)

Inflow

Subclavian artery 12 (38)

Truncus brachiocephalicus 20 (63)

Outflow

Right pulmonary artery 28 (88)

Left pulmonary artery 4 (13)

Heart lung machine 2 (6)

Absolute shunt size (mm) 3.5 (34)

Median shunt size/body weight ratio

(mm/kg)

1.21 (0.91.7)

C

O

N

G

E

N

I

T

A

L

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1097

cases with shunt clipping (shunt size reduction) or technical pro-

blems encountered during shunt construction. Heparin infusion

starting with 510 IU/kg/h, followed by therapeutic dose as early

as 2 h postoperatively, was planned if surgical bleeding was not

an issue. In effect, however, the therapeutic anticoagulation was

often achieved later than 2 h. Shunts without complications and

considered normal risk received aspirin in the long term.

Three patients did not have long-term anticoagulation/platelet

inhibitor medication: 2 who died early and 1 who survived with

early shunt thrombosis in a neonatal Ebsteins anomaly with

antegrade pulmonary ow.

All patients were evaluated postoperatively with trans-thoracic

echocardiography.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19

(SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables are presented

as numbers with percents and are compared using Fishers exact

test. Continuous variables are presented as median with range

and are compared between groups using the MannWhitney

test. P-values <0.05 were considered signicant.

RESULTS

Mortality

Three of the 32 (9%) patients died at a median of 3(115) days.

The details of patients who died are as presented in Table 3.

Lower body weight (P = 0.04) and bigger shunt size/kg of body

weight (P = 0.004) were signicant risk factors for mortality

(Table 4).

Shunt thrombosis

Acute shunt thrombosis was observed in 3 of the 32 (9%)

patients, none of whom died. These 3 patients had Ebsteins

anomaly with antegrade pulmonary ow (2.2 kg 3 mm right

MBTS), double outlet right ventricle-hypoplastic left ventricle

(LV)_pulmonary stenosis (2.9 kg 3 mm right MBTS) and unba-

lanced atrio-ventricular septal defect hypoplastic LV

d-transposition of great arteries_pulmonary stenosis (3 kg 3.5

mm left MBTS). All shunt thrombosis occurred within the rst

24 h and were diagnosed by echocardiography. Two patients

had shunt revision with evacuation of the thrombus. One patient

with stable saturation due to normal antegrade pulmonary ow

was not subjected to shunt revision. Shunt thrombosis could not

be statistically related to shunt size (P = 0.1) or shunt size/kg

body weight (P = 0.92). Early anticoagulation regimen (P = 0.33),

competitive blood ow (P = 1.0), diagnosis (P = 0.27), need for

cardiopulmonary bypass (P = 0.18), increased inotropic support

(P = 0.71) and shunt size reduction (P = 1.0) were not associated

with acute shunt thrombosis.

Inotropic support

Need for adrenalin 0.05 and/or noradrenaline 0.05 and/or

milrinone 0.75 g/kg/min was dened as normal inotropic

support. Accordingly, 6 of the 32 (19%) patients needed normal

inotropic support and 23 of the 32 (72%) needed higher ino-

tropic support. Three patients were without any ionotropic

support.

Decongestive therapy

Need for cardiac decongestive therapy (over and above that of

diuretics) was necessary in 10 of 29 survivors to discharge.

Decongestive therapy was required in 2 of 19 (20%) biventricular

hearts compared with 8 of 10 (80%) univentricular hearts

(P < 0.001), obviously resulting in a signicantly longer hospital

stay (P = 0.005). Bigger shunts were associated with the need for

decongestive therapy (P = 0.054).

Open thorax

The sternum was left open postoperatively in 11 (34%) patients.

Other complications

Postoperative complications included chylothorax, phrenic nerve

palsy, necrotizing enterocolitis and abdominal bleeding with

unclear focus in 1 patient each.

Corrective surgery

Of the 29 survivors, 28 (97%) have undergone corrective surgery

with takedown of the BT shunt at the time of this study. Ten

patients were subjected to a bidirectional Glenn anastomosis,

while 18 underwent a biventricular repair. None of the shunt

survivors died during or after the corrective surgery.

Fate of branch pulmonary artery

Seven of 28 patients (25%) had reconstruction of the branch pul-

monary artery at the distal shunt insertion site. Residual stenosis

after BT shunt takedown occurred in 6 patients. In 3 of the

patients, the stenosis occurred despite the pulmonary artery

being reconstructed, while in 3, the stenosis occurred without

the artery being reconstructed.

Era

A brief comparative analysis between 12 shunts in Era I and 20

shunts in Era II is depicted in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

An ideal shunt helps promote uniform growth of the pulmonary

arteries, without causing distortion. An excessive shunt results in

signicant diastolic run-off in the short term and elevated pul-

monary vascular resistance or impaired ventricular and atrioven-

tricular valve performance in the long term. Although various

types of shunts have been described [1, 711], it is the MBTS that

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1098

has become established as the procedure of choice [4, 12]. MBTS

continues to be a subject of academic interest, because of per-

sistent risks associated with this simple-looking procedure.

Sternotomy or thoracotomy

MBTS was classically performed through a thoracotomy.

However, recent trends have shown increasing preference for a

sternotomy approach [6]. A sternotomy saves the child from a

second scar, avoids morbid damage to the thorax with pro-

spects of late scoliosis, but more importantly, the target pul-

monary artery being intrapericardial, it is more accessible for

eventual reconstruction after takedown. Avoiding a thoracotomy

in the prospective Fontan patients has an added advantage of

reducing build-up of lung adhesions to the thoracic wall and

the consequent development of systemic-to-pulmonary artery

collaterals. Other disadvantages of a thoracotomy approach

enumerated in the literature include Horners syndrome, distor-

tion of lobar branch pulmonary arteries and preferential ow to

one lung with unbalanced growth [6]. Depending on the side of

the thoracotomy, it may not be always possible to perform

PDA ligation, but with a sternotomy, it is always possible. In the

end, whether or not to close the duct remains a strategic

decision [13].

The sternotomy approach does confront the surgeon with the

challenges of a central run-off from the systemic artery leading

to greater steal, low diastolic pressures, coronary malperfusion

and pulmonary hyperperfusion. In addition, the often-used

truncus brachiocephalicus to the right pulmonary artery shunt

may be at danger of being squashed between the dominant

aorta and the superior vena cava, for which the parietal pericar-

dial reection over the superior vena cava to the trachea should

be divided to create space for the shunt.

Table 3: Mortality details

Diagnosis Age

(days)

Weight

(kg)

Shunt size

(mm)

Cause of death Died

(Postop day)

DORV_TGA_PS 19 2.5 3.5 Cardiorespiratory

decompensation

15

Pulmonary atresia VSD, hepatopulmonary syndrome, catheter

perforation and emergency shunt

4 2.2 3.5 Cardiorespiratory

decompensation

1

Pulmonary atresia intact ventricular septum 6 2.4 4 Myocardial ischaemia 3 (ECMO)

DORV: double outlet right ventricle; TGA: transposition of great arteries; PS:pulmonary stenosis; ECMO: extra corporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 4: Risk factors for mortality

Variable Alive

n (%)

Dead

n (%)

P-value

N 29 3

Weight (kg) 2.94 (1.94.4) 2.37 (2.22.49) 0.04

Diagnosis

Biventricular hearts 19/29 (66) 2/3 (67) 1.00

Univentricular hearts 10/29 (34) 1/3 (33)

Competitive pulmonary flow 21/29 (72) 1/3 (33) 0.22

Use of heart lung machine 2/29 (7) 0/3 (0) 1.00

Size of shunt (mm):

3 8/29 (28) 0/3 (0) 0.47

3.5 17/29 (59) 2/3 (67)

4 4/29 (14) 1/3 (33)

Shunt size/kg body weight 1.19 (0.881.58) 1.59 (1.411.69) 0.004

Anticoagulation regimen:

1 LDH 7/28

a

(25) 0/2

c

(0) 0.38

2 ETH 4/28

a

(14) 1/2

c

(50)

3 LTH 17/28

a

(61) 1/2

c

(50)

Long-term anticoagulation 7/28

a

(25) 0/1

b

(0) 1.00

Postoperative high ionotropes 20/29 (69) 3/3 (100) 0.52

Shunt size reduction 3/29 (10) 2/3 (67) 0.056

Shunt thrombosis 3/29 (10) 0/3 (0) 1.00

SaO

2

postoperative (day of operation) 83 (7794) 85 (8090) 0.97

Hospital stay 23 (595) 3 (115) 0.02

LDH: low dose (10 IU/kg/h) heparin; ETH: early therapeutic heparin; LTH: late therapeutic heparin.

a

One patient data missing.

b

One patient on immediate ECMO was not analysed for acute anticoagulation regimen.

c

Two patients who died early were not analysed for long-term anticoagulation.

C

O

N

G

E

N

I

T

A

L

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1099

While the proposed alternative shunts such as Potts or

Waterston/Cooley shunts were difcult to regulate, the MBTS

ow is restricted by the size of the graft as also by the size of the

inow vessel.

While the Boston group [6] reported four times higher risk of

shunt failures through a thoracotomy when compared with a

sternotomy, Shauq et al. [13] have reported signicantly longer

ventilation time, inotropic support, intensive care unit (ICU) stay

and hospital stay in the sternotomy group. These ndings reect

the learning curve involved with shunts created through a

sternotomy.

Competitive ow and PDA strategy

A completely left open duct may be difcult to regulate in the

presence of a MBTS. With our technique of duct obliteration

using a silastic sling, one retains the possibility of quickly restor-

ing duct patency in the case of a shunt thrombosis. While a

patent duct imparts signicant safety in the case of a shunt

failure, some reports have associated patent duct with shunt

thrombosis [14]. Petrucci et al. (Society of Thoracic Surgeons

[STS] database) have shown no association between closed duct

and the risk of composite morbidity [15]. Closing or keeping the

duct open during the MBTS procedure has advantages and dis-

advantages and, hence remains in the end, an individual

decision.

Mortality

In spite of overall improvement in results [5], mortality reported

ranges from 2.3 to 16% [15]. Our overall postoperative mortality

was 9.4%. Low body weight (P = 0.041) and bigger shunt size/kg

body weight (P = 0.011) were factors associated with post-

operative mortality. There was a trend towards signicance

between the need for postoperative shunt size reduction and

mortality (P = 0.056). These ndings point towards over-shunting

as a possible indicator of mortality in our series. The Boston

group has reported a mortality of 9 of 102 (8.7%) patients, with

indications that excessive pulmonary blood ow could have con-

tributed to mortality in the sternotomy group. Multivariate risk

factors for mortality in their analysis included small graft size, left

MBTS and male sex [6]. The same group also suggested the use

Table 5: Comparison between eras

Variable Era I (200407)

n (%)

Era II (200811)

n (%)

P-value

N 12 (38) 20 (62)

Diagnosis

Biventricular hearts 6/12 (50) 15/20 (75) 0.25

Univentricular hearts 6/12 (50) 5/20 (25)

Weight (kg) 2.89 (2.24.4) 2.93 (1.93.8) 0.99

Size of shunt (mm) 3.5 (3.54) 3.5 (33.5) 0.002

Shunt size/weight 1.24 (0.911.69) 1.16 (0.881.58) 0.13

Presence of competitive blood flow 7/12 (58) 15/20 (75) 0.44

Use of HLM 0/12 (0) 3/20 (10) 0.52

Shunt distribution, mm (in %)

3 0/12 (0) 8/20 (40) 0.001

3.5 7/12 (58) 12/20 (60)

4 5/12 (42) 0/20 (0)

Right vs left 11/20 (92) right 17/20 (85) right 1.00

1/12 (8) left 3/20 (15) left

Site of take-off (truncus brachiocephalicus vs subclavian artery) 10/12 (83) vs 2/12 (17) 10/20 (50) vs 10/20 (50) 0.08

Early anticoagulation strategy

Low dose 3/10 (30) 4/20 (20) 0.71

Early therapeutic 1/10 (10) 4/20 (20)

Late therapeutic (as defined in Table 4) 6/10 (60) 12/20 (60)

Long-term anticoagulation

Aspirin 8/10 (80) 14/19 (74) 1.00

Therapeutic 2/10 (20) 5/19 (26)

Postoperative ionotropic support

None 1/12 (8) 2/20 (10) 0.48

Normal 1/12 (8) 5/20 (25)

High

a

10/12 (83) 13/20 (65)

Need for shunt reduction 3/12 (25) 2/20 (10) 0.34

Decongestive therapy (more than diuretics) 6/9 (67) 4/20 (20) 0.03

Duration of ventilation 2 (115) 1.5 (09) 0.53

ICU stay 4 (115) 5 (113) 0.39

Duration of hospital stay 18.5 (195) 22.5 (584) 0.69

Mortality 3/12 (25) 0/20 (0) 0.04

Shunt thrombosis 0/12 (0) 3/20 (15) 0.27

SaO

2

before takedown 82 (7293) 81.5 (7394) 0.66

Residual branch PA stenosis at shunt insertion site 4/9 (44) 1/15 (7) 0.05

a

Normal ionotropic support is defined as adrenalin 0.05 and/or noradrenaline 0.05 and/or milrinone 0.75 g/kg/min.

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1100

of smaller (3.5 mm) shunts through a sternotomy approach

instead of the 4-mm shunts for the thoracotomy approach. An

STS database harvest study [15] has identied preoperative venti-

lation, pulmonary atresia_intact ventricular septum, univentricu-

lar hearts and weight <3 kg as risk factors for mortality.

Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum, when specic-

ally analysed, did not come out as a signicant risk factor for

mortality in our cohort, probably because of small numbers.

While Alkhulai et al. [16] identied weight <2 kg and preopera-

tive ventilation, Rao et al. [17] identied restrictive atrial septal

defect, univentricular physiology and postoperative intervention

as risk factors for mortality.

Shunt thrombosis

Shunt thrombosis is a grave complication of the MBTS proced-

ure. Our overall acute shunt thrombosis of (3 of 32) 9.4% corre-

sponds with those of (9 of 76) 11.8% reported from Bristol and

(14 of 102) 13.7% reported from Boston [6]. We could not show

an association between smaller shunt size and occurrence of

thrombosis, probably because of the small numbers. Tsai et al.

[18] and Tamisier et al. [12] have suggested that young age and

smaller size are signicantly related to shunt thrombosis. Other

reports have also linked weight <2 kg [16] and weight <3.6 kg [19]

to shunt thrombosis. Gedicke et al. [14] have found weight <3 kg,

high preoperative haemoglobin (>18 g/dl) and a postoperative

patent duct as signicant factors for shunt thrombosis.

Anticoagulation-coagulopathy

Although an association between an anticoagulation regimen

and shunt thrombosis could not be established in our study, it

does not belittle the role of postoperative anticoagulation, par-

ticularly in high-risk patients. Al Jubair et al. [20] have shown,

less-shunt failure occurs if heparin is given before clamping. An

early postoperative phase with a fresh anastomosis, coupled with

phases of low systemic pressures, pulmonary hypertension, ex-

ternal compression and resulting stasis, can initiate thrombus

formation. It is these uncertainties that can be positively inu-

enced by early anticoagulation. Li et al. [21] have demonstrated a

benecial effect of acetylsalicylic acid in infants palliated with a

shunt, with reduced incidence of shunt thrombosis and death.

Another prospective study has shown the benecial effect of

haemodilution with a signicantly higher shunt patency rate [22].

Rare coagulopathies, such as protein C deciency [23], and

primary antiphospholipid syndrome [24] have also been

reported to cause shunt thrombosis.

Late shunt obstruction

We have not observed any late shunt thrombosis in this series of

patients. This has been reported as a cause in up to 15% of

out-of-hospital mortalities [14, 15]. Wells et al. [25] have observed

>50% obstruction of the MBTS in 21% of their patients and have

identied a shunt size of <4 mm to be a risk factor for high-

grade stenosis (>50%).

Era

While the cohort did not change over time in terms of most

demographic and procedural variables, shunt size was signi-

cantly lower in the latter half of the series when compared with

the former half. Shunt thrombosis was higher in the later era,

but did not reach statistical signicance. These ndings may indi-

cate that small shunts are prone to shunt thrombosis. Mortality

as well as need for cardiac decongestive therapy was signicantly

higher in the previous era. With time, while mortality was

avoided, shunt thrombosis remained worrisome. While shunt

thrombosis morbidity could be partially attributed to the tech-

nique, the importance of optimal intensive postoperative man-

agement cannot be overemphasized. Interestingly, in spite of

smaller shunt size selection in the later era, transcutaneous satur-

ation before shunt takedown was 82% in both the eras. This

implies that the shunt ow was adequately regulated by the

artery from which the shunt was sourced.

LIMITATIONS

This is a retrospective study with a small patient cohort, which

may not be powered enough to identify all risk factors contribut-

ing to the various end points. The series being spread over a

time frame of 8 years, even generalized improvements in opera-

tive technique and perioperative care may alone account for the

improvements in outcome.

CONCLUSION

In spite of increasing condence with primary neonatal intracardiac

repairs, the MBTS continues to be indicated for malformations

of the univentricular pathway. Although seemingly innocuous,

the MBTS procedure is associated with signicant morbidity and

mortality. While small shunts may have a tendency to shunt throm-

bosis, large shunts may lead to pulmonary over-circulation and

volume loading of the heart. Various studies have identied

low body weight, small shunt size, over-shunting, univentricular

heartsspecically pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular

septum, to be risk factors associated with postoperative morbidity

and mortality. It appears that timely and efcient early anticoagula-

tion as well as long-term antiplatelet therapy may help reduce the

risk of early and late shunt dysfunction.

Conict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

[1] Blalock A, Taussig HB. Landmark article May 19, 1945: the surgical treat-

ment of malformations of the heart in which there is pulmonary stenosis

or pulmonary atresia. By Alfred Blalock and Helen B Taussig. JAMA 1984;

251:212338.

[2] Mavroudis C, Backer CL. Palliative operations. In: Mavroudis C, Backer CL

(eds). Pediatric Cardiac Surgery. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003,

16070.

[3] Geiss D, Williams WG, Lindsay WK, Rowe RD. Upper extremity gangrene: a

complication of subclavian artery division. Ann Thorac Surg 1980;30:4879.

[4] de Leval MR, McKay R, Jones M, Stark J, Macartney FJ. Modied

Blalock-Taussig shunt. Use of subclavian artery orice as ow regulator

C

O

N

G

E

N

I

T

A

L

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1101

in prosthetic systemic-pulmonary artery shunts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg

1981;81:1129.

[5] Williams JA, Bansal AK, Kim BJ, Nwakanma LU, Patel ND, Seth AK et al.

Two thousand Blalock-Taussig shunts: a six-decade experience. Ann

Thorac Surg 2007;84:20705; discussion 20705.

[6] Odim J, Portzky M, Zurakowski D, Wernovsky G, Burke RP, Mayer JE Jr

et al. Sternotomy approach for the modied Blalock-Taussig shunt.

Circulation 1995;92:II25661.

[7] Potts WJ, Smith S, Gibson S. Anastomosis of the aorta to a pulmonary

artery: certain types in congenital heart disease. J Am Med Assoc 1946;

132:62731.

[8] Waterston DJ. Treatment of Fallots tetralogy in children under 1 year of

age. Rozhl Chir 1962;41:1813.

[9] Cooley DA, Hallman GL. Intrapericardial aortic-right pulmonary arterial

anastomosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1966;122:10846.

[10] Gazzaniga AB, Elliott MP, Sperling DR, Dietrick WR, Eiseman JT,

McRae DM et al. Microporous expanded polytetrauoroethylene

arterial prosthesis for construction of aortopulmonary shunts: experi-

mental and clinical results. Ann Thorac Surg 1976;21:3227.

[11] Amato JJ, Marbey ML, Bush C, Galdieri RJ, Cotroneo JV, Bushong J.

Systemic-pulmonary polytetrauoroethylene shunts in palliative opera-

tions for congenital heart disease. Revival of the central shunt. J Thorac

Cardiovasc Surg 1988;95:629.

[12] Tamisier D, Vouhe PR, Vernant F, Leca F, Massot C, Neveux JY. Modied

Blalock-Taussig shunts: results in infants less than 3 months of age.

Ann Thorac Surg 1990;49:797801.

[13] Shauq A, Agarwal V, Karunaratne A, Gladman G, Pozzi M, Kaarne M

et al. Surgical approaches to the Blalock shunt: does the approach

matter? Heart Lung Circ 2010;19:4604.

[14] Gedicke M, Morgan G, Parry A, Martin R, Tulloh R. Risk factors for acute

shunt blockage in children after modied Blalock-Taussig shunt opera-

tions. Heart Vessels 2010;25:4059.

[15] Petrucci O, OBrien SM, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP, Manning PB, Eghtesady P.

Risk factors for mortality and morbidity after the neonatal

Blalock-Taussig shunt procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:64251;

discussion 64151.

[16] Alkhulai AM, Lacour-Gayet F, Serraf A, Belli E, Planche C. Systemic

pulmonary shunts in neonates: early clinical outcome and choice of

surgical approach. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;69:1499504.

[17] Rao MS, Bhan A, Talwar S, Sharma R, Choudhary SK, Airan B et al.

Modied Blalock-Taussing shunt in neonates: determinants of immediate

outcome. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2000;8:33943.

[18] Tsai KT, Chang CH, Lin PJ. Modied Blalock-Taussig shunt: statistical

analysis of potential factors inuencing shunt outcome. J Cardiovasc

Surg (Torino) 1996;37:14952.

[19] Bove EL, Kohman L, Sereika S, Byrum CJ, Kavey RE, Blackman MS et al.

The modied Blalock-Taussig shunt: analysis of adequacy and duration

of palliation. Circulation 1987;76:III1923.

[20] Al Jubair KA, Al Fagih MR, Al Jarallah AS, Al Yousef S, Ali Khan MA,

Ashmeg A et al. Results of 546 Blalock-Taussig shunts performed in 478

patients. Cardiol Young 1998;8:48690.

[21] Li JS, Yow E, Berezny KY, Rhodes JF, Bokesch PM, Charpie JR et al.

Clinical outcomes of palliative surgery including a systemic-to-

pulmonary artery shunt in infants with cyanotic congenital heart disease:

does aspirin make a difference? Circulation 2007;116:2937.

[22] Sahoo TK, Chauhan S, Sahu M, Bisoi A, Kiran U. Effects of hemodilution

on outcome after modied Blalock-Taussig shunt operation in children

with cyanotic congenital heart disease. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2007;

21:17983.

[23] Watanabe M, Aoki M, Fujiwara T. Thrombotic occlusion of Blalock-

Taussig shunt in a patient with unnoticed protein C deciency. Gen

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:5446.

[24] Deally C, Hancock BJ, Giddins N, Hawkins L, Odim J. Primary antipho-

spholipid syndrome: a cause of catastrophic shunt thrombosis in the

newborn. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1999;40:2614.

[25] Wells WJ, Yu RJ, Batra AS, Monforte H, Sintek C, Starnes VA. Obstruction

in modied Blalock shunts: a quantitative analysis with clinical correl-

ation. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:20726.

V. Dirks et al. / European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 1102

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Autism AssessmentDokumen37 halamanAutism AssessmentRafael Martins94% (16)

- Commentary For Academic Writing For Graduate StudentsDokumen123 halamanCommentary For Academic Writing For Graduate StudentsJakler Nichele100% (1)

- Jesus The Liberator - Jon SorbinoDokumen321 halamanJesus The Liberator - Jon SorbinoavaMotivatorije93% (15)

- Redbook - ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMA PDFDokumen323 halamanRedbook - ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMA PDFrizka100% (1)

- Nails Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery Richard K Scher MD, C Ralph DanielDokumen319 halamanNails Diagnosis, Therapy, Surgery Richard K Scher MD, C Ralph DanieldrBelum ada peringkat

- Cardiac CatheterizationDokumen9 halamanCardiac CatheterizationAnurag Gupta100% (1)

- Business Plan Analysis - 08 1: SFHN/SJ&G Oxalepsy (Oxcarbazipine300 & 600 MG)Dokumen63 halamanBusiness Plan Analysis - 08 1: SFHN/SJ&G Oxalepsy (Oxcarbazipine300 & 600 MG)Muhammad SalmanBelum ada peringkat

- Immediate Dental Implant Placement Into Infected vs. Non-Infected Sockets: A Meta-AnalysisDokumen7 halamanImmediate Dental Implant Placement Into Infected vs. Non-Infected Sockets: A Meta-Analysismarlene tamayoBelum ada peringkat

- Finely Dispersed ParticlesDokumen936 halamanFinely Dispersed ParticlesJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Perioperative Care For CABG PatientsDokumen32 halamanPerioperative Care For CABG PatientsAya EyadBelum ada peringkat

- Drummond Methods For The Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes PDFDokumen461 halamanDrummond Methods For The Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes PDFGerman Camilo Viracacha Lopez80% (10)

- Restraints Assignment on Definitions, Types, Indications and Nurses RoleDokumen8 halamanRestraints Assignment on Definitions, Types, Indications and Nurses RolemacmohitBelum ada peringkat

- Results With Continuous Cardiopulmonary Bypass For The Bidirectional Cavopulmonary Anastomosis - ProQuestDokumen7 halamanResults With Continuous Cardiopulmonary Bypass For The Bidirectional Cavopulmonary Anastomosis - ProQuestWilliam WiryawanBelum ada peringkat

- Aortic Valve Bypass: Experience From Denmark: Original Article - Adult CardiacDokumen5 halamanAortic Valve Bypass: Experience From Denmark: Original Article - Adult CardiacmoplkiBelum ada peringkat

- Case Report: Middle Aortic Syndrome Treated by Implantation of An Advanta V12 Large Diameter StentDokumen3 halamanCase Report: Middle Aortic Syndrome Treated by Implantation of An Advanta V12 Large Diameter StentLenardR.ApazaBelum ada peringkat

- Extracorporeal Life Support in Pediatric Cardiac DysfunctionDokumen5 halamanExtracorporeal Life Support in Pediatric Cardiac DysfunctionNoor Aida AriyaniBelum ada peringkat

- Detection of Myocardial Infraction Monisha C M - 17bei0092: Select, Vit VelloreDokumen8 halamanDetection of Myocardial Infraction Monisha C M - 17bei0092: Select, Vit VelloresubramanianBelum ada peringkat

- Hollamby Mitchell s5001226 Case 1 DtgaDokumen13 halamanHollamby Mitchell s5001226 Case 1 Dtgaapi-299009880Belum ada peringkat

- Echocardiography Dissertation IdeasDokumen8 halamanEchocardiography Dissertation IdeasWhoCanWriteMyPaperForMeCanada100% (1)

- Children: The Pulmonary Circulation in The Single Ventricle PatientDokumen12 halamanChildren: The Pulmonary Circulation in The Single Ventricle PatientFernando PinedaBelum ada peringkat

- The Fate of The Distal Aorta After Repair of Acute Type A Aortic DissectionDokumen10 halamanThe Fate of The Distal Aorta After Repair of Acute Type A Aortic Dissectionapi-160333876Belum ada peringkat

- Benefit of Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis For Acute Iliofemoral DVT: Myth or Reality?Dokumen2 halamanBenefit of Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis For Acute Iliofemoral DVT: Myth or Reality?Anas YahyaBelum ada peringkat

- Eriksen Et Al-2002-Clinical Cardiology PDFDokumen5 halamanEriksen Et Al-2002-Clinical Cardiology PDFmedskyqqBelum ada peringkat

- Surgical Management of Tracheal Compression Caused by Mediastinal Goiter: Is Extracorporeal Circulation Requisite钥Dokumen3 halamanSurgical Management of Tracheal Compression Caused by Mediastinal Goiter: Is Extracorporeal Circulation Requisite钥Indra W SaputraBelum ada peringkat

- Intermittent Warm Blood CardioplegiaDokumen8 halamanIntermittent Warm Blood Cardioplegiacem berkay duranBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Coronary Syndrome inDokumen2 halamanAcute Coronary Syndrome inpaul_preda_bvBelum ada peringkat

- Risk Factors For Intraoperative Massive Transfusion in Pediatric Liver Transplantation: A Multivariate AnalysisDokumen8 halamanRisk Factors For Intraoperative Massive Transfusion in Pediatric Liver Transplantation: A Multivariate AnalysisSanti ParambangBelum ada peringkat

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDokumen11 halamanNew England Journal Medicine: The ofahmadto80Belum ada peringkat

- Bmri2016 3741426Dokumen7 halamanBmri2016 3741426MandaBelum ada peringkat

- Percutaneous Aortic Valve Implantation: The Anesthesiologist PerspectiveDokumen11 halamanPercutaneous Aortic Valve Implantation: The Anesthesiologist Perspectiveserena7205Belum ada peringkat

- Echocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: EAE/ASE Recommendations For Clinical PracticeDokumen25 halamanEchocardiographic Assessment of Valve Stenosis: EAE/ASE Recommendations For Clinical PracticeLucy ManuriBelum ada peringkat

- Heart Failure 2006Dokumen5 halamanHeart Failure 2006Samer FarhanBelum ada peringkat

- Hour Pathophysiologic Approach To The Golden: Review of A Major Pulmonary EmbolismDokumen31 halamanHour Pathophysiologic Approach To The Golden: Review of A Major Pulmonary EmbolismSilvio SillitanoBelum ada peringkat

- Minimally Invasive Tricuspid Valve Surgery A Single Institution ExperienceDokumen2 halamanMinimally Invasive Tricuspid Valve Surgery A Single Institution ExperienceNguyen Tran ThuyBelum ada peringkat

- Evolving Science of Trauma Resus 2021-06-17 17-57-30Dokumen22 halamanEvolving Science of Trauma Resus 2021-06-17 17-57-30Paulina CastilloBelum ada peringkat

- Acute Myocardial Infarction: Primary Angioplasty: Coronary DiseaseDokumen5 halamanAcute Myocardial Infarction: Primary Angioplasty: Coronary DiseaseGuțu SergheiBelum ada peringkat

- E-Poster Mumbai FinalDokumen5 halamanE-Poster Mumbai FinalSuman SagarBelum ada peringkat

- Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect, and MAPCAs, Neonate Rehab On PADokumen7 halamanPulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect, and MAPCAs, Neonate Rehab On PAdinaBelum ada peringkat

- Diagnosis and Management of Splanchnic Ischemia: Ioannis E Koutroubakis, MD, PHD, Assistant Professor of MedicineDokumen12 halamanDiagnosis and Management of Splanchnic Ischemia: Ioannis E Koutroubakis, MD, PHD, Assistant Professor of MedicineIgorCotagaBelum ada peringkat

- Pulmonary Endarterectomy: Experience and Lessons Learned in 1,500 CasesDokumen8 halamanPulmonary Endarterectomy: Experience and Lessons Learned in 1,500 CasesRoxana Maria MunteanuBelum ada peringkat

- Chy Lo ThoraxDokumen6 halamanChy Lo ThoraxGina LutvianaBelum ada peringkat

- 2022 - Anesthetic Management For Open Thoracoabdominal and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm RepairDokumen14 halaman2022 - Anesthetic Management For Open Thoracoabdominal and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm RepairLaura Camila RiveraBelum ada peringkat

- AblacionDokumen7 halamanAblaciontomasvainsteinBelum ada peringkat

- Analysis of Post Operative Systemic To Pulmonary Artery Shunt FailureDokumen5 halamanAnalysis of Post Operative Systemic To Pulmonary Artery Shunt FailurePaul HartingBelum ada peringkat

- Swinkels Et Al - Effect of Aortic Cross-Clamp Time On LateDokumen7 halamanSwinkels Et Al - Effect of Aortic Cross-Clamp Time On LateMurat MukharyamovBelum ada peringkat

- Aas - Hasta IqDokumen8 halamanAas - Hasta IqFrancisco A. Perez JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- Is There A Choice of Palliation For Tetralogy of Fallot? : Editorial CommentDokumen2 halamanIs There A Choice of Palliation For Tetralogy of Fallot? : Editorial CommentOkky Winang SaktyawanBelum ada peringkat

- Relatia Dintre Arteroscleroza Si Colesterol SericDokumen7 halamanRelatia Dintre Arteroscleroza Si Colesterol SericBeniamin BorotaBelum ada peringkat

- Kim2012Dokumen5 halamanKim2012Stefanie MelisaBelum ada peringkat

- Results With Respect To Intraprocedural Myocardial Contrast EchocardiographyDokumen16 halamanResults With Respect To Intraprocedural Myocardial Contrast EchocardiographySavira Tapi-TapiBelum ada peringkat

- Abdominal TraumaDokumen34 halamanAbdominal Traumalaurz95Belum ada peringkat

- Avoiding Revascularization With Lifestyle Changes: The Multicenter Lifestyle Demonstration ProjectDokumen5 halamanAvoiding Revascularization With Lifestyle Changes: The Multicenter Lifestyle Demonstration ProjectNag Mallesh RaoBelum ada peringkat

- How I Use Ultrasound in Cardiac Arrest: EditorialDokumen4 halamanHow I Use Ultrasound in Cardiac Arrest: EditorialHelder LezamaBelum ada peringkat

- Damage Control ResuscitationDokumen15 halamanDamage Control ResuscitationLizzy BennetBelum ada peringkat

- RVOT Stenting in TOF PatientDokumen31 halamanRVOT Stenting in TOF PatientHannaTashiaClaudiaBelum ada peringkat

- Concomitant Bentall Operation Plus Aortic Arch Replacement SurgeryDokumen7 halamanConcomitant Bentall Operation Plus Aortic Arch Replacement Surgeryprofarmah6150Belum ada peringkat

- Physiology and Cardiovascular Effect of Severe Tension Pneumothorax in A Porcine ModelDokumen8 halamanPhysiology and Cardiovascular Effect of Severe Tension Pneumothorax in A Porcine Modelflik_gantengBelum ada peringkat

- 1 s2.0 S0929664608602041 MainDokumen9 halaman1 s2.0 S0929664608602041 MainEko SiswantoBelum ada peringkat

- Coronary Artery Occlusions Diagnosed by Transthoracic DopplerDokumen11 halamanCoronary Artery Occlusions Diagnosed by Transthoracic DopplerNag Mallesh RaoBelum ada peringkat

- Korean QX Total Pulm Veins 2010Dokumen5 halamanKorean QX Total Pulm Veins 2010Dr. LicónBelum ada peringkat

- LP Surgery ChestDokumen6 halamanLP Surgery Chestangelmd83Belum ada peringkat

- Case 12669Dokumen15 halamanCase 12669Putrisuci AndytichaBelum ada peringkat

- Anesthetic Management of An Atrial Septal Defect in Adult-Case ReportDokumen3 halamanAnesthetic Management of An Atrial Septal Defect in Adult-Case ReportNikhil YadavBelum ada peringkat

- Final DesertationDokumen96 halamanFinal DesertationMobin Ur Rehman KhanBelum ada peringkat

- 2000 - Stamm Et Al. - Surgery For Bilateral Outflow Tract Obstruction in Elastin ArteriopathyDokumen9 halaman2000 - Stamm Et Al. - Surgery For Bilateral Outflow Tract Obstruction in Elastin ArteriopathybanupluBelum ada peringkat

- Pediatric Echocardiography TechniquesDokumen17 halamanPediatric Echocardiography Techniquesraviks34Belum ada peringkat

- Clinical Handbook of Cardiac ElectrophysiologyDari EverandClinical Handbook of Cardiac ElectrophysiologyBenedict M. GloverBelum ada peringkat

- Complications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookDari EverandComplications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookAlistair LindsayBelum ada peringkat

- Effective Intermolecular Interaction Potentials of Gaseous Fluorine, Chlorine, Bromine, and IodineDokumen14 halamanEffective Intermolecular Interaction Potentials of Gaseous Fluorine, Chlorine, Bromine, and IodineJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1978) The Structure of Liquid Bromine II. Theory and Computer SimulationDokumen25 halaman(1978) The Structure of Liquid Bromine II. Theory and Computer SimulationJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Strachan-Unsupervised Learning-Based Multiscale Model of Thermochemistry in 1,3,5-Trinitro-1,3,5-Triazinane (RDX) - J-Phys-Chem-ADokumen15 halamanStrachan-Unsupervised Learning-Based Multiscale Model of Thermochemistry in 1,3,5-Trinitro-1,3,5-Triazinane (RDX) - J-Phys-Chem-AJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1996) A General Equation of State For Supercritical Fluid Mixtures and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Mixture PVTX PropertiesDokumen8 halaman(1996) A General Equation of State For Supercritical Fluid Mixtures and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Mixture PVTX PropertiesJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1998) High-Order Dinite-Difference Schemes For Numerical Simulation of Hypersonic Boundary-Layer Transition PDFDokumen48 halaman(1998) High-Order Dinite-Difference Schemes For Numerical Simulation of Hypersonic Boundary-Layer Transition PDFJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Olmi 2017 Meas. Sci. Technol. 28 014003Dokumen7 halamanOlmi 2017 Meas. Sci. Technol. 28 014003Jakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (2005) Viscosity of Pure Supercritical FluidsDokumen12 halaman(2005) Viscosity of Pure Supercritical FluidsJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Molecular Dynamics Calculation Ofthe Dielectric Constant Dynamic Properties of A Fluid of 2-D Stockmayer MoleculesDokumen20 halamanMolecular Dynamics Calculation Ofthe Dielectric Constant Dynamic Properties of A Fluid of 2-D Stockmayer MoleculesJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1973) Monte Carlo Studies of The Dielectric Properties of Water-Like Models PDFDokumen4 halaman(1973) Monte Carlo Studies of The Dielectric Properties of Water-Like Models PDFJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1973) Monte Carlo Studies of The Dielectric Properties of Water-Like Models PDFDokumen4 halaman(1973) Monte Carlo Studies of The Dielectric Properties of Water-Like Models PDFJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Accurately Calculating Dielectric Constant from MD SimulationsDokumen4 halamanAccurately Calculating Dielectric Constant from MD SimulationsJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1964) Correlations in The Motions of Atoms in Liquid ArgonDokumen7 halaman(1964) Correlations in The Motions of Atoms in Liquid ArgonJakler Nichele100% (1)

- (1959) Studies in Molecular Dynamics. I. General MethodDokumen8 halaman(1959) Studies in Molecular Dynamics. I. General MethodJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Phenomena in Microgravity: Past, Present, and FutureDokumen52 halamanCritical Phenomena in Microgravity: Past, Present, and FutureJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Critical Phenomena in Microgravity: Past, Present, and FutureDokumen52 halamanCritical Phenomena in Microgravity: Past, Present, and FutureJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Nichele Et Al. - 2017 - Accurate Calculation of Near-Critical Heat Capacities CP and CV of Argon Using Molecular Dynamics-AnnotatedDokumen6 halamanNichele Et Al. - 2017 - Accurate Calculation of Near-Critical Heat Capacities CP and CV of Argon Using Molecular Dynamics-AnnotatedJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Scilab4Matlab2.6 1.0Dokumen124 halamanScilab4Matlab2.6 1.0Muhammad Adeel AkramBelum ada peringkat

- (2003) The Phase Diagram of The 2C-LJ Model As Obtained From Computer Simulation and Wertheim's Thermodynamic Perturbation TheoryDokumen11 halaman(2003) The Phase Diagram of The 2C-LJ Model As Obtained From Computer Simulation and Wertheim's Thermodynamic Perturbation TheoryJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Controle em MarcapassosDokumen5 halamanControle em MarcapassosJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- SPH LAMMPS UserguideDokumen23 halamanSPH LAMMPS UserguideJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Carolyn J. Sharp, Irony and Meaning in The Hebrew Bible. Bloomington: IndianaDokumen2 halamanCarolyn J. Sharp, Irony and Meaning in The Hebrew Bible. Bloomington: IndianaJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- The History and Applications of the Ising Model in Statistical PhysicsDokumen13 halamanThe History and Applications of the Ising Model in Statistical PhysicsJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (1966) Volume Viscosity in Liquid Argon at High PressuresDokumen9 halaman(1966) Volume Viscosity in Liquid Argon at High PressuresJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Nooma #08 - DustDokumen17 halamanNooma #08 - DustJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- (2008) A Lagrangian, Stochastic Modeling Framework For Multi-Phase Flow in Porous MediaDokumen19 halaman(2008) A Lagrangian, Stochastic Modeling Framework For Multi-Phase Flow in Porous MediaJakler NicheleBelum ada peringkat

- Open Bone Grafting: Papineau TechniqueDokumen7 halamanOpen Bone Grafting: Papineau TechniqueAlireza MirzasadeghiBelum ada peringkat

- Dialog Convincing, Consoling, Persuading, Encouraging, Apologizing, Disclaiming, RequestingDokumen4 halamanDialog Convincing, Consoling, Persuading, Encouraging, Apologizing, Disclaiming, RequestingmeliaBelum ada peringkat

- Gender-Dysphoric-Incongruene Persons, Guidelines JCEM 2017Dokumen35 halamanGender-Dysphoric-Incongruene Persons, Guidelines JCEM 2017Manel EMBelum ada peringkat

- Prasugrel and RosuvastatinDokumen7 halamanPrasugrel and RosuvastatinMohammad Shahbaz AlamBelum ada peringkat

- Ob Assessment FinalDokumen10 halamanOb Assessment Finalapi-204875536Belum ada peringkat

- Olivia Millsop - Case Study Docx 1202Dokumen11 halamanOlivia Millsop - Case Study Docx 1202api-345759649Belum ada peringkat

- Coliform BacteriaDokumen4 halamanColiform BacteriaLalu Novan SatriaBelum ada peringkat

- Jdvar 08 00237Dokumen3 halamanJdvar 08 00237Shane CapstickBelum ada peringkat

- Sush Unity Haemotology-1700Dokumen51 halamanSush Unity Haemotology-1700Dr-Jahanzaib GondalBelum ada peringkat

- Objective Structured Clinical Examination (Osce) : Examinee'S Perception at Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Jimma UniversityDokumen6 halamanObjective Structured Clinical Examination (Osce) : Examinee'S Perception at Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Jimma UniversityNuurBelum ada peringkat

- US vs. Barium for Pediatric GERDDokumen6 halamanUS vs. Barium for Pediatric GERDAndreea KBelum ada peringkat

- Fistulas Enterocutaneas MaingotDokumen20 halamanFistulas Enterocutaneas MaingotroyvillafrancaBelum ada peringkat

- Performance Review NPDokumen11 halamanPerformance Review NPtmleBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing Standards for Labour RoomDokumen3 halamanNursing Standards for Labour RoomRenita ChrisBelum ada peringkat

- Poster ProjectDokumen1 halamanPoster Projectapi-291204444Belum ada peringkat

- 328 IndexDokumen29 halaman328 IndexDafi SanBelum ada peringkat

- Thesis On HPV VaccineDokumen8 halamanThesis On HPV Vaccinegjftqhnp100% (2)

- Eliminate Papillomas and Warts at Home in 1 Treatment Course - PapiSTOP® PHDokumen9 halamanEliminate Papillomas and Warts at Home in 1 Treatment Course - PapiSTOP® PHkiratuz1998Belum ada peringkat

- Силлабус PChD 1 engDokumen22 halamanСиллабус PChD 1 engaaccvBelum ada peringkat

- CAMTC Certified Massage Therapist Chuck LeeDokumen1 halamanCAMTC Certified Massage Therapist Chuck LeeChuck LeeBelum ada peringkat

- Mindful Practice: Ronald M. EpsteinDokumen8 halamanMindful Practice: Ronald M. EpsteinphilosophienBelum ada peringkat

- Cochlear ImplantsDokumen20 halamanCochlear ImplantsLong An ĐỗBelum ada peringkat

- Geistlich Bio-Oss Collagen and Geistlich Bio-Gide in Extraction SocketsDokumen6 halamanGeistlich Bio-Oss Collagen and Geistlich Bio-Gide in Extraction SocketsErdeli StefaniaBelum ada peringkat

- U.S. clinical observerships help IMGs gain experienceDokumen8 halamanU.S. clinical observerships help IMGs gain experienceAkshit ChitkaraBelum ada peringkat