Carl Rogers

Diunggah oleh

jolscHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Carl Rogers

Diunggah oleh

jolscHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Theory

Rogers was discouraged by the emphasis on cognitivism in education. He believed this was

responsible for the loss of excitement and enthusiasm for learning. Rogers' point of view

emphasized the inclusion of feelings and emotions in education. He believed that education and

therapy shared similar goals of personal change and self-knowing. He was interested in learning that

leads to personal growth and development, as was Maslow.

His 1983 book, Freedom to Learn for the 80's presented his full theory of experiential learning. He

believed that the highest levels of significant learning included personal involvement at both the

affective and cognitive levels, were self-initiated, were so pervasive they could change attitudes,

behavior, and in some cases, even the personality of the learner. Learnings needed to be evaluated

by the learner and take on meaning as part of the total experience.

Rogers outlined attitudes which characterized a true facilitator of learning:

1. Realness - the instructor should not present a "front" or "facade" but should strive to be aware of

his/her own feelings and to communicate them in the classroom context. The instructor should

present genuineness, and engage in direct personal encounters with the learner.

2. Prizing the Learner - This characteristic includes acceptance and trust of each individual student.

The instructor must be able to accept the fear, hesitation, apathy, and goals of the learner.

3. Empathic Understanding - The instructor can understand the student's reactions from the inside.

Rogers warned that a non-judgmental teacher is sure to arouse suspicion in older students and

adults, because they have been "conned" so many times. The wise teacher is aware of this and can

accept their initial distrust and apprehension as new relationships between teacher and students are

built.

Some idea of what Rogers learned about methods of facilitating learning can be obtained from his

guidelines for facilitating learning (Rogers, 1969, p. 164).

1. It is very important for the facilitator to set the initial mood or climate of the group or class

experience.

2. The facilitator helps to elicit and clarify the purposes of the individuals in the class as well as the

more general purposes of the group

Rogers goes on to say about the facilitator: If he is not fearful of accepting contradictory purposes

and conflicting aims, if he is able to permit the individual a sense of freedom in stating what they

would like to do, then he is helping to create a climate for learning.

3. The facilitator relies upon the desire of each student to implement those purposes which have

meaning for the student, as the motivational force behind significant learning.

4. The facilitator endeavours to organize and make easily available the widest possible range of

resources for learning.

5. The facilitator regards himself/herself as a flexible resource to be utilized by the group.

6. In responding to expressions in the classroom group, the facilitator accepts both the intellectual

content and the emotionalized attitudes, endeavouring to give each aspect the approximate degree

of emphasis which it has for the individual or the group.

7. As the acceptant classroom climate becomes established, the facilitator is able increasingly to

become a participant learner, a member of the group, expressing his/her views as those of one

individual only.

8. The facilitator takes the initiative in sharing himself/herself with the group feelings as well as

thoughts in ways which neither demand nor impose, but represent simply a personal sharing which

students may take or leave.

9. Throughout the classroom experience, the facilitator remains alert to the expressions indicative of

deep or strong feelings.

Rogers goes on to say that these feelings should be understood and the empathic understanding

should be communicated.

10. In his functioning as a facilitator of learning, the leader endeavours to recognize and accept

his/her own limitations.

Rogers also had much to say about education. Freedom to Learn is a classic statement of educational

possibility. The concern with people speaking about their experiences in order to theorize and learn

from them, the concept of the human organism as a whole, and the belief in the possibilities of

human action have their parallels in the work of John Dewey. Carl Rogers was able to join these with

therapeutic insights and the belief, borne out of his practice experience that the client often knows

better in how to proceed than the therapist. He was also a committed practitioner who looked to his

own experiences (and was, thus, difficult to dismiss as an academic). In short, he offered a new way

to break with earlier traditions.

Carl Rogers was also a gifted teacher. His approach grew from his orientation in one-to-one

professional encounters. He saw himself as a facilitator one who creates an environment for

engagement, learning, and growth. He provided educators with some fascinating and important

questions with regard to their way of being with participants and the processes they might employ.

One of his more fascinating studies was on feedback. He discovered five ways in which we give

feedback. They are listed below in the order in which they occur most frequently in daily

conversations (notice that we make judgments more often than we try to understand):

o Evaluative: Make a judgment about the worth, goodness, or appropriateness of the other

person's statement

o Interpretive: Paraphrasing - attempt to explain what the other persons statement means

o Supportive: Attempt to assist or bolster the other communicator

o Probing: Attempt to gain additional information, continue the discussion, or clarify a point

o Understanding: Attempt to discover completely what the other communicator means by her

statements

Nondirective," "client-centered," and "person-centered." are the terms Rogers used successively,

at different points in his career, for his method. This method involves removing obstacles so the

client can move forward, freeing him or her for normal growth and development. It emphasizes

being fully present with the client and helping the latter truly feel his or her own feelings, desires,

etc.. Being "nondirective" lets the client deal with what he or she considers important, at his or her

own pace.

Education. Rogers views our schools as generally rigid, bureaucratic institutions which are resistant

to change. Applied to education, his approach becomes "student-centered learning" in which the

students are trusted to participate in developing and to take charge of their own learning agendas.

The most difficult thing in teaching is to let learn.

Empathic understanding: to try to take in and accept a client's perceptions and feelings as if they

were your own, but without losing your boundary/sense of selve.

Personal growth. Rogers' clients tend to move away from facades, away from "oughts," and away

from pleasing others as a goal in itself. Then tend to move toward being real, toward self-direction,

and toward positively valuing oneself and one's own feelings. Then learn to prefer the excitement

of being a process to being something fixed and static. They come to value an openness to inner

and outer experiences, sensitivity-to and acceptance-of others as they are, and develop greater

ability achieve close relationships.

Student-centred learning (also called child-centred learning) is an approach to education focusing

on the needs of the students, rather than those of others involved in the educational process, such

as teachers and administrators. This approach has many implications for the design of curriculum,

course content, and interactivity of courses. For instance, a student-centred course may address the

needs of a particular student audience to learn how to solve some job-related problems using some

aspects of mathematics. In contrast, a course focused on learning mathematics might choose areas

of mathematics to cover and methods of teaching which would be considered irrelevant by the

student. Student-centred learning, that is, putting students first, is in stark contrast to existing

establishment/teacher-centred lecturing and careerism. Student-centred learning is focused on the

student's needs, abilities, interests, and learning styles with the teacher as a facilitator of learning.

This classroom teaching method acknowledges student voice as central to the learning experience

for every learner. Teacher-centred learning has the teacher at its centre in an active role and

students in a passive, receptive role. Student-centred learning requires students to be active,

responsible participants in their own learning.

Background

Traditionally, teachers were at the centre of learning with students assuming a receptive role in their

education. With research showing how people learn, traditional curriculum approaches to

instruction where teachers were at the centre gave way to new ways of teaching and learning. Key

amongst these changes is the idea that students actively construct their own learning (known

as constructivism). Theorists like John Dewey, Jean Piaget, and Lev Vygotsky whose collective work

focused on how students learn is primarily responsible for the move to student-centred

learning. Carl Rogers' ideas about the formation of the individual also contributed to student-

centred learning. Student centred-learning means reversing the traditional teacher-centred

understanding of the learning process and putting students at the centre of the learning process.

Assessment of student-centred learning

One of the most critical differences between student-centered learning and teacher-centred

learning is in assessment. In student-centred learning, students participate in the evaluation of their

learning. This means that students are involved in deciding how to demonstrate their learning.

Developing assessment that supports learning and motivation is essential to the success of student-

centred approaches. One of the main reasons teachers resist student-centred learning is the view of

assessment as problematic in practice. Since teacher-assigned grades are so tightly woven into the

fabric of schools, expected by students, parents and administrators alike, allowing students to

participate in assessment is somewhat contentious.

He thought the role of the teacher was, of course, to facilitate learning, but also to encourage

healthy development. This would require the teacher to have a general positive regard toward the

student, as well as empathy and genuineness. Unlike Freudian theorists and behaviorists, Rogers

actually had a positive view of human nature and believed that with the right developmental

environment, people could become, well, good: independent yet connected and confident of

themselves yet flexible in their beliefs. He believed teachers were an integral part of this healthy

development, which I think we certainly can be

In the early 1960s, Albert Bandura began a series of writings that challenged the older explanations

of imitative learning and expand the topic into what is now referred to as Observational

Learning. According to Bandura, observation learning may or may not involve imitation. For example

if you see someone driving in front of you hit a pothole, and then you swerve to miss it you

learned from observational learning, not imitation (if you learned from imitation then you would

also hit the pothole). What you learned was the information you processed cognitively and then

acted upon. Observational learning is much more complex than simple imitation. Bandura's theory is

often referred to as social learning theory as it emphasizes the role of vicarious experience

(observation) of people impacting people (models). Modeling has several affects on learners:

o Acquisition - New responses are learned by observing the model.

o Inhibition - A response that otherwise may be made is changed when the observer sees a

model being punished.

o Disinhibition - A reduction in fear by observing a model's behavior go unpunished in a feared

activity.

o Facilitation - A model elicits from an observer a response that has already been learned.

o Creativity - Observing several models performing and then adapting a combination of

characteristics or styles.

In one of his experiments, twenty-four preschool children were assigned to each of three conditions.

One group observed aggressive adult models; a second observed inhibited non-aggressive models;

while the control group had no prior exposure to the models. Subjects were then tested for the

amount of imitative as well as non-imitative aggression performed in a new situation in the absence

of the models. Comparison of the subjects' behavior in the generalization situation revealed that

subjects exposed to aggressive models reproduced a good deal of aggression resembling that of the

models, and that their mean scores differed markedly from those of subjects in the non-aggressive

and control groups. Subjects in the aggressive condition also exhibited significantly more partially

imitative and non-imitative aggressive behavior and were generally less inhibited in their behavior

than subjects in the non-aggressive condition.

Some of Bandura's other contributions include:

Cuing

Cuing refers to actions that make stimuli more salient and thus more likely to be noticed. Attention

can be cued directly, e.g., Watch this!, or indirectly by telling your students, I wonder what will

happen when I push this button? In general, cuing includes the directing of attention through

pointing, holding objects up for viewing, telling learners where to look, or asking questions that will

cause them to process information and find the appropriate stimulus.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura also researched self-efficacy. This is part of our "self system" that helps us to evaluate our

performance. Perceived self-efficacy refers to one's impression of what one is capable of doing. This

comes from a variety of sources, such as personal accomplishments and failures, seeing others who

are similar to oneself, and verbal persuasion. Verbal persuasion may temporarily convince people

that they should try or avoid some task, but in the final analysis it is one's direct or vicarious

experience with success or failure that will most strongly influence one's self-efficacy. For example, a

coach may fire-up her team before a game by telling the team how great they are, but the

enthusiasm will be short-lived if the opposing team is clearly superior. People with high perceived

self-efficacy try more, accomplish more, and persist longer at a task than people with low perceived

self-efficacy. Bandura speculated that this is because people with high perceived self-efficacy tend to

have more control over their environment and therefore experience less uncertainty. Also, one's

perceived self-efficacy may not correspond to one's real self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is self-constructed

and is like confidence, but is definite, not abstracted

The dark side to self-efficacy is it can lead to only approaching easy tasks, obsessing over easy or

hard tasks at the occlusion of more important life goals, or learned helplessness (a type of

depression) if self-efficacy is too low

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Final Paper AsdDokumen24 halamanFinal Paper Asdapi-410097887Belum ada peringkat

- DBT Therapy CritiqueDokumen34 halamanDBT Therapy CritiqueMariel SalgadoBelum ada peringkat

- Social Interest ScaleDokumen2 halamanSocial Interest ScaleMuskanBelum ada peringkat

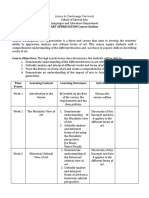

- ARTAPP Course OutlineDokumen3 halamanARTAPP Course OutlineEmmanuel ApuliBelum ada peringkat

- Psychological Resilience and Coping Strategies of High School Students Based On Certain Variables PDFDokumen16 halamanPsychological Resilience and Coping Strategies of High School Students Based On Certain Variables PDFCarla Si MarianBelum ada peringkat

- Contracting For Group SupervisionDokumen5 halamanContracting For Group Supervisionapi-626136134Belum ada peringkat

- Guilford Press FlyerDokumen2 halamanGuilford Press FlyerskkundorBelum ada peringkat

- Theories: Behaviorism Learning TheoryDokumen6 halamanTheories: Behaviorism Learning TheorystfuBelum ada peringkat

- PBQ-SF - Structure of The PBQ-SF - Smallest Space Analyses 2012Dokumen7 halamanPBQ-SF - Structure of The PBQ-SF - Smallest Space Analyses 2012DoniLeiteBelum ada peringkat

- Research Methodology: Course Code:9078Dokumen161 halamanResearch Methodology: Course Code:9078Maryam BatoolBelum ada peringkat

- Neuropsychology of FlowDokumen7 halamanNeuropsychology of FlowSoft RobotBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 1 Introduction of PsychodiagnosticsDokumen10 halamanChapter 1 Introduction of Psychodiagnosticsrinku jainBelum ada peringkat

- Teda Dyslexia in The FieDokumen26 halamanTeda Dyslexia in The Fieapi-264019256Belum ada peringkat

- Movie Analysis AssignmentDokumen4 halamanMovie Analysis AssignmentAshleyBelum ada peringkat

- Behaviorist ApproachDokumen7 halamanBehaviorist Approachapple macBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review On Narrative TherapyDokumen8 halamanLiterature Review On Narrative Therapyc5eyjfnt100% (1)

- The Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoDokumen12 halamanThe Hypothesis As Dialogue: An Interview With Paolo BertrandoFausto Adrián Rodríguez LópezBelum ada peringkat

- Session 10 - Reflective WritingDokumen6 halamanSession 10 - Reflective WritingKhurramIftikharBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 9 and 10 - Language (Sternberg)Dokumen8 halamanChapter 9 and 10 - Language (Sternberg)Paul JacalanBelum ada peringkat

- 01 - Lapworth - CH - 01 PsychologyDokumen16 halaman01 - Lapworth - CH - 01 PsychologykadekpramithaBelum ada peringkat

- George Kelly's Personal Construct TheoryDokumen18 halamanGeorge Kelly's Personal Construct TheoryDidem KaraosmanoğluBelum ada peringkat

- Advantages and Limitations of Group CounsellingDokumen9 halamanAdvantages and Limitations of Group CounsellingThila IshuBelum ada peringkat

- Definitions of Intelligence PDFDokumen12 halamanDefinitions of Intelligence PDFJotaEle09Belum ada peringkat

- The Use of Metaphor in Psychotherapy: ArticleDokumen12 halamanThe Use of Metaphor in Psychotherapy: ArticleDana StefanescuBelum ada peringkat

- Critique On Psychoanalytic Theory and Adlerian Therapy RD 011709Dokumen4 halamanCritique On Psychoanalytic Theory and Adlerian Therapy RD 011709Lavelle100% (3)

- Trait and Factor - Holland2Dokumen11 halamanTrait and Factor - Holland2Matet Sales AsuncionBelum ada peringkat

- When Caring Hurts: The Silence Burnout of SonographersDokumen5 halamanWhen Caring Hurts: The Silence Burnout of SonographersCarlos BarradasBelum ada peringkat

- Book Review of 'Blending Technologies in Second Language ClassroomsDokumen4 halamanBook Review of 'Blending Technologies in Second Language ClassroomsMiguel VarelaBelum ada peringkat

- How Superhero Comics May Boost AltruismDokumen25 halamanHow Superhero Comics May Boost AltruismClaudio SanhuezaBelum ada peringkat

- Carl Rogers 19 Propositions Decoded PDFDokumen5 halamanCarl Rogers 19 Propositions Decoded PDFAlia AlamBelum ada peringkat

- Nature, Goals, Definition and Scope of PsychologyDokumen9 halamanNature, Goals, Definition and Scope of PsychologyNikhil MaripiBelum ada peringkat

- DaydreamingDokumen3 halamanDaydreamingapi-355153539100% (1)

- Gazzola - EDPC 501 - Fall 2016 SyllabusDokumen10 halamanGazzola - EDPC 501 - Fall 2016 SyllabusJonathan LimBelum ada peringkat

- Social IntelligenceDokumen18 halamanSocial IntelligenceRose DeppBelum ada peringkat

- Humanistic Orientation in Social Sciences and Practices / Orientarea Umanista in Stiintele Si Practicile Sociale / Petru StefaroiDokumen44 halamanHumanistic Orientation in Social Sciences and Practices / Orientarea Umanista in Stiintele Si Practicile Sociale / Petru Stefaroipetru stefaroiBelum ada peringkat

- Guilt and The Moral DimensionDokumen3 halamanGuilt and The Moral DimensionÉd TâghžBelum ada peringkat

- Lecture 10.1 Rogers ReviewerDokumen4 halamanLecture 10.1 Rogers ReviewerStefani Kate LiaoBelum ada peringkat

- Meaning of ResearchDokumen11 halamanMeaning of ResearchRahulBelum ada peringkat

- Social Psychology Course by Wesleyan UniversityDokumen10 halamanSocial Psychology Course by Wesleyan UniversityTolly BeBelum ada peringkat

- Bourdieu S Concept of Reflexivity As MetaliteracyDokumen15 halamanBourdieu S Concept of Reflexivity As MetaliteracyekiourtiBelum ada peringkat

- Language Attitude and Sociolinguistic BehaviourDokumen20 halamanLanguage Attitude and Sociolinguistic BehaviourcrisseveroBelum ada peringkat

- TSL 3109Dokumen42 halamanTSL 3109Myra UngauBelum ada peringkat

- Teaching Psychomotor SkillsDokumen3 halamanTeaching Psychomotor SkillsjovenlouBelum ada peringkat

- The Littering Attitude Scale PDFDokumen15 halamanThe Littering Attitude Scale PDFAnonymous jvb1l3huqbBelum ada peringkat

- Competency Based Training and Assessment (CBT&A)Dokumen19 halamanCompetency Based Training and Assessment (CBT&A)Mahmudur Rahman SadmanBelum ada peringkat

- DIASS NotesDokumen10 halamanDIASS NotesErica Ann GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- A Way of Being, Bringing Mindfulness Into Individual Therapy PDFDokumen14 halamanA Way of Being, Bringing Mindfulness Into Individual Therapy PDFJC Barrientos100% (1)

- Psychodrama Therapy for Emotional InsightsDokumen5 halamanPsychodrama Therapy for Emotional InsightsRocio- FisogBelum ada peringkat

- Career Adapt-Abilities Scale-Short Form (CAAS-SF) : Construction and ValidationDokumen14 halamanCareer Adapt-Abilities Scale-Short Form (CAAS-SF) : Construction and ValidationAnonymous 2TOWteL8JBelum ada peringkat

- KV Petrides, A Drian Furnham Và Norah - Tri Tue Cam XucDokumen4 halamanKV Petrides, A Drian Furnham Và Norah - Tri Tue Cam XucNguyễn Huỳnh Trúc100% (1)

- Resilience Building in StudentsDokumen15 halamanResilience Building in StudentsRiana dityaBelum ada peringkat

- Dual Career Couple (1) ProjectDokumen3 halamanDual Career Couple (1) ProjectAnkitaChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- PsychophysicsDokumen16 halamanPsychophysicsNavneet DhimanBelum ada peringkat

- Alfred AdlerDokumen17 halamanAlfred Adlerlehsem20006985100% (1)

- George Kelly - Personal Construct TheoryDokumen16 halamanGeorge Kelly - Personal Construct TheoryThavasi mari selvam NBelum ada peringkat

- Learning Strategies InventoryDokumen18 halamanLearning Strategies InventoryArlene AmorimBelum ada peringkat

- Construct ValidityDokumen9 halamanConstruct ValidityGad AguilarBelum ada peringkat

- The Role of Community Psychologist in The 21st CenturyDokumen4 halamanThe Role of Community Psychologist in The 21st CenturyAfrika EmceeAfrikaVEVOBelum ada peringkat

- Catharsis Definition and Historical UnderstandingDokumen2 halamanCatharsis Definition and Historical UnderstandingNupur Vora MankadBelum ada peringkat

- Second Year Module PsychologyDokumen74 halamanSecond Year Module PsychologyAluyandro Roblander MoongaBelum ada peringkat

- TextDokumen1 halamanTextjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Malaysia: Toy Museum Pulau PinangDokumen2 halamanMalaysia: Toy Museum Pulau PinangjolscBelum ada peringkat

- English Exercises 1Dokumen4 halamanEnglish Exercises 1jolsc100% (1)

- Topic 6 Testing and Evaluation of Reading SkillsDokumen30 halamanTopic 6 Testing and Evaluation of Reading SkillsGrazilleBeth Damia SylvesterBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation Week 5Dokumen1 halamanEvaluation Week 5jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Action Research ScheduleDokumen2 halamanAction Research SchedulejolscBelum ada peringkat

- Double Bubble MapDokumen1 halamanDouble Bubble MapjolscBelum ada peringkat

- V CertDokumen1 halamanV CertjolscBelum ada peringkat

- 10 1 1 468 1050Dokumen34 halaman10 1 1 468 1050jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Action Research ScheduleDokumen2 halamanAction Research SchedulejolscBelum ada peringkat

- Y3 Lesson Plan Writing Body Parts of FishDokumen2 halamanY3 Lesson Plan Writing Body Parts of FishjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation Week 4Dokumen1 halamanEvaluation Week 4jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Sticker RPH - ArabDokumen2 halamanSticker RPH - ArabjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Irregularpasttensecards 1Dokumen6 halamanIrregularpasttensecards 1Nia MohdBelum ada peringkat

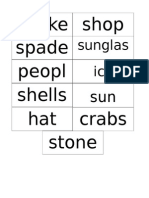

- Shop Peopl e Spade Bucke T: Ice Cream Sunglas SesDokumen1 halamanShop Peopl e Spade Bucke T: Ice Cream Sunglas SesjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Appendix IDokumen1 halamanAppendix IjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Research QuestionairesDokumen2 halamanResearch QuestionairesjolscBelum ada peringkat

- NAME: - CLASS: - Listen and Draw The Tourist Attractions in The Correct StateDokumen2 halamanNAME: - CLASS: - Listen and Draw The Tourist Attractions in The Correct StatejolscBelum ada peringkat

- Y3 Lesson Plan Writing Body Parts of FishDokumen2 halamanY3 Lesson Plan Writing Body Parts of FishjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Softly Hungrily Happily Quickly Heavily NeatlyDokumen1 halamanSoftly Hungrily Happily Quickly Heavily NeatlyjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation Week 2Dokumen1 halamanEvaluation Week 2jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation Week 3Dokumen1 halamanEvaluation Week 3jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Evaluation Week 1Dokumen1 halamanEvaluation Week 1jolscBelum ada peringkat

- B.Ed TESL Practicum Report 2012Dokumen1 halamanB.Ed TESL Practicum Report 2012jolscBelum ada peringkat

- 6flow Map Template1Dokumen1 halaman6flow Map Template1jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Teachers: Figure 1: Management of Teaching and Learning (Cited in Modul PGSR, 2010)Dokumen1 halamanTeachers: Figure 1: Management of Teaching and Learning (Cited in Modul PGSR, 2010)jolscBelum ada peringkat

- Brace Map - Part To WholeDokumen1 halamanBrace Map - Part To WholeConan AlanBelum ada peringkat

- Islamic Edu.Dokumen5 halamanIslamic Edu.jolscBelum ada peringkat

- 4tree MapMEDIADokumen1 halaman4tree MapMEDIAjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Essential Is MDokumen9 halamanEssential Is MjolscBelum ada peringkat

- Parent Guide To Jolly PhonicsDokumen3 halamanParent Guide To Jolly Phonicsapi-370777564Belum ada peringkat

- IIM Kashipur Wat-Pi KitDokumen26 halamanIIM Kashipur Wat-Pi Kitsaheb1670% (1)

- Accreditation and QA in TVETDokumen61 halamanAccreditation and QA in TVETRoslan.Affandi2351Belum ada peringkat

- Learning To Listen in English 2Dokumen5 halamanLearning To Listen in English 2hipoliticoBelum ada peringkat

- Personal StatementDokumen3 halamanPersonal Statementapi-314556685Belum ada peringkat

- DCLR Mapeh Output g8 q1.1Dokumen5 halamanDCLR Mapeh Output g8 q1.1Felita DayaBelum ada peringkat

- Igcse English Language B 2012 Jan Paper 1 Source BookletDokumen4 halamanIgcse English Language B 2012 Jan Paper 1 Source BookletShenal PereraBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Test 1. AchievementDokumen1 halamanTypes of Test 1. AchievementTengku Nurhydayatul Tengku AriffinBelum ada peringkat

- Third Periodical Test in Mathematics ViDokumen5 halamanThird Periodical Test in Mathematics Viprincess teodoroBelum ada peringkat

- Multiplication ArraysDokumen4 halamanMultiplication ArraysDigi-BlockBelum ada peringkat

- Material AutenticoDokumen27 halamanMaterial AutenticoAlon0911Belum ada peringkat

- Profile of Plantation Polytechnic of LPP IndonesiaDokumen15 halamanProfile of Plantation Polytechnic of LPP IndonesiaRantau SilalahiBelum ada peringkat

- Math Paper 1Dokumen4 halamanMath Paper 1wencelausBelum ada peringkat

- NUML MBA Marketing Principles Course OutlineDokumen3 halamanNUML MBA Marketing Principles Course OutlineCupyCake MaLiya HaSanBelum ada peringkat

- Pronunciation Practice: Reading Text 4Dokumen1 halamanPronunciation Practice: Reading Text 4zakboBelum ada peringkat

- JPN4850 Structure of Japanese Wehmeyer SyllabusDokumen8 halamanJPN4850 Structure of Japanese Wehmeyer Syllabusnehal vaghela0% (1)

- Human Resource Management: Oberoi HotelsDokumen9 halamanHuman Resource Management: Oberoi Hotelsraul_181290Belum ada peringkat

- International Student GTE Assessment FormDokumen9 halamanInternational Student GTE Assessment FormAnup Lal RajbahakBelum ada peringkat

- Brittany Nicol Resume November 2014Dokumen2 halamanBrittany Nicol Resume November 2014api-214253401Belum ada peringkat

- Lesson 1: Introduction To Market EconomyDokumen5 halamanLesson 1: Introduction To Market Economyapi-302452610Belum ada peringkat

- EL SWD Fact Sheet - InteractiveDokumen2 halamanEL SWD Fact Sheet - Interactivecorey_c_mitchellBelum ada peringkat

- FinalnagudperoangconclusionsagudDokumen44 halamanFinalnagudperoangconclusionsagudapi-313036013Belum ada peringkat

- Eseu 3 Uk Tuition FeesDokumen1 halamanEseu 3 Uk Tuition Feesiustina matei17Belum ada peringkat

- Using Flashcards To Teach LanguagesDokumen5 halamanUsing Flashcards To Teach LanguagesEFL Classroom 2.0Belum ada peringkat

- Federal Government PhD Scholarships in SwitzerlandDokumen4 halamanFederal Government PhD Scholarships in SwitzerlandPedro VargasBelum ada peringkat

- Pattana Bamboo SchoolDokumen2 halamanPattana Bamboo SchoolMulat Pinoy-Kabataan News NetworkBelum ada peringkat

- Effects of High National Exam StandardsDokumen2 halamanEffects of High National Exam StandardsYopi NovitasariBelum ada peringkat

- Tara HinchenDokumen1 halamanTara Hinchenapi-482296622Belum ada peringkat

- June 2016 Question Paper 31Dokumen8 halamanJune 2016 Question Paper 31ZafBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson PlanDokumen6 halamanLesson PlanCarmie Lactaotao DasallaBelum ada peringkat

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeDari EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeBelum ada peringkat

- The Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossDari EverandThe Tennis Partner: A Doctor's Story of Friendship and LossPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (4)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityDari EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (13)

- The Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsDari EverandThe Garden Within: Where the War with Your Emotions Ends and Your Most Powerful Life BeginsBelum ada peringkat

- Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfDari EverandCodependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (87)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionDari EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (402)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedDari EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (78)

- EVERYTHING/NOTHING/SOMEONE: A MemoirDari EverandEVERYTHING/NOTHING/SOMEONE: A MemoirPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (44)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsDari EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (3)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsDari EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsBelum ada peringkat

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessDari EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (327)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeDari EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (253)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaDari EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Dari EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (110)

- Secure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimeDari EverandSecure Love: Create a Relationship That Lasts a LifetimePenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (17)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneDari EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreenePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (233)

- The Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingDari EverandThe Happiness Trap: How to Stop Struggling and Start LivingPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassDari EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (22)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisDari EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (3)

- Summary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisDari EverandSummary: Limitless: Upgrade Your Brain, Learn Anything Faster, and Unlock Your Exceptional Life By Jim Kwik: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (8)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryDari EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (44)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsDari EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsBelum ada peringkat

- Hearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIDari EverandHearts of Darkness: Serial Killers, The Behavioral Science Unit, and My Life as a Woman in the FBIPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (19)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductDari EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductPenilaian: 5 dari 5 bintang5/5 (31)