Early Amniotomy

Diunggah oleh

Indah Mayang SariDeskripsi Asli:

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Early Amniotomy

Diunggah oleh

Indah Mayang SariHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Research

www. AJOG.org

OBSTETRICS

The efficacy of early amniotomy in nulliparous

labor induction: a randomized controlled trial

George A. Macones, MD; Alison Cahill, MD; David M. Stamilio, MD; Anthony O. Odibo, MD

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to assess whether early am-

niotomy reduces the duration of labor or increases the proportion of

subjects who are delivered within 24 hours in nulliparous patients who

undergo labor induction.

STUDY DESIGN: We performed a randomized controlled trial that com-

pared early amniotomy to standard management in nulliparous labor inductions. Inclusion criteria were nulliparity, singleton, term gestation,

and a need for labor induction. Subjects were assigned randomly to

early amniotomy (artificial rupture of membranes, 4 cm) or to standard treatment. There were 2 primary outcomes: (1) time from induc-

tion initiation to delivery and (2) the proportion of women who delivered

within 24 hours.

RESULTS: Early amniotomy shortens the time to delivery by 2 hours

(19.0 vs 21.3 hours) and increases the proportion of induced nulliparous

women who deliver within 24 hours (68% vs 56%). These improvements in

labor outcomes did not come at the expense of increased complications.

CONCLUSION: Early amniotomy is a safe and efficacious adjunct in nul-

liparous labor inductions.

Key words: amniotomy, nulliparous labor induction

Cite this article as: Macones GA, Cahill A, Stamilio DM, et al. The efficacy of early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:403.e1-5.

ates of labor induction are rising.

Recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics demonstrate an

induction rate of 22% in 2006, which

was more than double what it was in

1990 and impacted 900,000 births in

the United States that year.1 Although

many recent studies have offered evidence for the improvement in methods

for labor induction, 2-7 the induction of

labor remains a significant risk factor for

cesarean delivery,8,9 which highlights the

critical need for additional tools to refine

induction practice.

Amniotomy, generally thought to be

low-tech, inexpensive, and safe, has received little research attention, and stud-

From the Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Washington University in St. Louis

School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO.

Received Feb. 27, 2012; revised June 1, 2012;

accepted Aug. 21, 2012.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Reprints: George A. Macones, MD, Professor

and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, Washington University in St Louis,

School of Medicine, 4911 Barnes Jewish

Hospital Plaza, St. Louis, MO 63110.

maconesg@wustl.edu.

0002-9378/$36.00

2012 Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2012.08.032

ies to date have neglected to investigate

the efficacy of amniotomy in nulliparous

women, despite the fact that more inductions are performed in nulliparous

women than their multiparous peers.1

Based on clinical trials from those in

spontaneous labor,10 early amniotomy

timing in labor inductions may shorten

the duration of labor. Clinical concern

for the rare complications of umbilical

cord prolapse and theoretic concerns

that rupturing the membranes earlier

will lead to a longer overall duration of

rupture of membranes with potentially

increased rates of chorioamnionitis,

neonatal sepsis, and neonatal intensive

care unit (NICU) admission have limited the empiric use of the practice of

amniotomy in nulliparous labor inductions without level I evidence to

support it.

The specific aim of this study was to

assess whether early amniotomy, defined

as artificial rupture of the membranes, at

4-cm dilation, reduces the duration of

labor or increases the proportion of subjects delivered within 24 hours in term

nulliparous patients who undergo labor

induction. We also sought to assess the

safety of early amniotomy, as measured

by adverse obstetric outcomes and measures of maternal and neonatal infectious morbidities.

M ETHODS

We performed an unblinded, randomized controlled trial at Washington University in St. Louis and the University of

Pennsylvania with approval from the Institutional Review Boards at both institutions. Inclusion criteria for this clinical

trial were nulliparity, singleton, term

gestation (defined as 37 weeks 0 days),

and a need for labor induction as determined by the treating physician. Exclusion criteria included HIV infection or

cervical dilation of 4 cm at admission

examination.

Eligible subjects were approached by

trained research nurses and were offered

enrollment into the clinical trial. Patients

who consented were then randomly assigned to early amniotomy, which was

defined as artificial rupture of the membranes at 4 cm or to standard management, which was amniotomy at 4 cm

dilation. In the early amniotomy group,

amniotomy was performed as early as

could be done safely. Decisions about the

exact timing of rupture (after random

assignment) were made by a team that

included residents, fellows, and attendings. There were no specific instructions

given regarding the timing of amniotomy

in the standard treatment group; this decision was left to the treating physicians. The

NOVEMBER 2012 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology

403.e1

Research

Obstetrics

www.AJOG.org

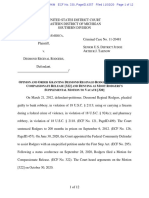

FIGURE

Flowchart

749 assessed for eligibility

164 excluded

84 not meeting inclusion criteria

80 refused to participate

0 other reasons

585 randomized

292 assigned to early amniotomy

270 received intervention as assigned

22 did not receive assigned intervention

(Clinical concern)

293 assigned to standard management

280 received intervention as assigned

13 did not receive assigned intervention

(Clinical concern)

0 lost to follow-up

0 lost to follow-up

292 included in analysis

0 excluded from analysis

293 included in analysis

0 excluded from analysis

Macones. Early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012.

primary method of induction was at the

discretion of the treating physician, as were

all other intrapartum/postpartum decisions. Random assignment was accomplished centrally. A permuted block

randomization procedure was used to

formulate assignment lists to assure close

to equal numbers of subjects in each treatment group. A uniform block size of 4 was

used.

There were 2 primary outcomes. The

first was time from initiation of induction, defined as time at delivery of the

first induction method to delivery. The

second was the proportion of women delivered within 24 hours from the initiation of induction. Although it may seem

unusual to have 2 primary endpoints, we

believed that both were equally clinically

relevant and should be treated as primary outcomes. This decision was made

a priori. We also assessed a number of

403.e2

secondary endpoints that included cesarean delivery rates and indications for

cesarean delivery, chorioamnionitis (oral

temperature 38C during labor), postpartum fever (oral temperature 38C on

2 separate occasions 6 hours apart, 24

hours from delivery), wound infection

(defined as purulent discharge from the

incision), endomyometritis (defined as

fundal tenderness and fever that require

treatment with antibiotics), NICU admission, and suspected neonatal sepsis. Trained

research nurses collected all baseline information, information on the course of labor,

and information on maternal and neonatal

outcomes.

Statistical analyses were performed

with the intent-to-treat principle. Continuous outcomes were compared with

the use of the Student t test or MannWhitney U dependent on their distributions; dichotomous outcomes were as-

American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2012

sessed with 2 tests or Fisher exact test

where appropriate. Time to delivery was

not normally distributed and was compared with the use of the Mann-Whitney

U test. Relative risks by group and 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for the percent of women who delivered within 24 hours and each of the

secondary outcomes. Our sample size

estimate was based on 1 of our primary

outcomes: the proportion of women

who delivered within 24 hours. We assumed an alpha error of .05, a beta error

of .20 (or 80% power), an incidence of

delivery within 24 hours of 50% based on

published data, a minimum detectable

relative risk of 0.75, and a 1:1 allocation

ratio. With these assumptions in mind,

we estimated that we would need 290

subjects per group. This strategy for

sample size calculation gave us tremendous power for our second primary outcome, time to delivery (a continuous

measure). Specifically, we estimated a

priori that we had 95% power to detect a

2-hour reduction in time to delivery.

R ESULTS

Seven hundred forty-nine women were

screened for eligibility; 84 women (11.2%)

were deemed ineligible by exclusion criteria. Of the 635 eligible nulliparous women,

585 women (92%) consented and were assigned randomly (Figure); 292 women

were assigned to the early amniotomy

group, and 293 women were assigned to

standard treatment. Those who agreed to

participate and those who did not were

similar in terms of baseline characteristics

(age, gestational age, preexisting medical

conditions). The groups were well-balanced with regards to demographics and

maternal medical conditions; the mean

gestational age at induction was similar between the groups (Table 1). The admission

cervical dilation was also similar between

the groups. Likewise, the indications for labor induction were similar between the

groups. The 2 most common indications

for induction were 40-week gestations

and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. The other category for indication for

induction had a variety of uncommon indications for induction, which included

maternal request/social factors (eg, dis-

Obstetrics

www.AJOG.org

tance from hospital) and oligohydramnios

(Table 2).

Methods for induction were similar

between the early amniotomy and standard treatment groups. Most women received misoprostol; approximately 30%

of the women received a Foley bulb. The

induction method categories are not mutually exclusive, because many women received multiple agents. In fact, 73% of

women in both groups received 1 agent

for induction. As expected, with regards to

timing of amniotomy, the early amniotomy group was ruptured earlier than

the standard treatment group. Twentytwo women who were assigned randomly

to early amniotomy were ruptured after 4

cm of dilation; 13 women who were assigned randomly to standard treatment

were ruptured at 4 cm.

The primary results of this study are

given in Table 3. The average time from

the start of induction to delivery was

shortened by slightly 2 hours in the

early amniotomy group (19.0 vs 21.3

hours, respectively; P .04) compared

with those with standard treatment. This

difference in length of labor occurred

mainly in the first stage of labor, which

was defined as time from random assignment to complete cervical dilation. A

higher proportion of women in the early

amniotomy group were delivered within

24 hours of the initiation of induction

(68% vs 56%, respectively; P .002).

Despite these differences in length of labor and delivery within 24 hours, there

was no difference in the rate of cesarean

deliveries. The rate of chorioamnionitis

was increased numerically in the early

amniotomy group (11.5% v. 8.5%, respectively; P .22), although this difference was not statistically significant.

Likewise, there were 2 cord prolapses in

the early amniotomy group, and none in

the standard treatment group.

Selected neonatal outcomes are shown

in Table 4. There was no increase in the rate

of confirmed or suspected neonatal sepsis

or admission to the special care nursery or

NICU in women who underwent early

amniotomy compared with those who experienced standard care. The infants born

to women with cord prolapse both did

well, with umbilical arterial pH 7.20 and

5-minute Apgar score.

Research

TABLE 1

Baseline characteristics

Early amniotomy

(n 292)

Variable

Standard therapy

(n 293)

P value

Maternal age, y

22.7 5.8

23.3 6.2

.17

African American race, %

72

68

.30

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Diabetes mellitus, %

3.9

3.5

.81

5.2

.32

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Chronic hypertension, %

7.2

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

2a

Body mass index, kg/m

28 4.2

28 3.9

.90

GBS, %

29

30

.66

Pitocin, %

93

93

.87

Misoprostol, %

67

69

.70

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Cervidil, %

6.8

8.4

.45

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Foley bulb, %

27

30

.43

More than 1 agent, %

73

73

.80

Epidural anesthesia, %

92

94

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

.88

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

a

Admission dilation, cm

1.1 1.03

1.1 0.97

.54

Dilation at rupture of membranes, cm

3.2

7.4

.001

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

a

Station at rupture of membranes

1 1.2

1 1.5

.50

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

a

6.2 3.0

Cervical examinations, n

5.9 3.4

.67

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

a

3323 516

Birthweight, g

3311 566

.78

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

a

39.7 1.4

Gestational age, wk

39.5 1.4

.16

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

GBS, Group B streptococcus.

a

Data are given as mean SD.

Macones. Early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012.

C OMMENT

Although these differences in duration

of labor and proportion of women delivered within 24 hours may seem to be intermediate outcomes, we would argue

that these are good surrogates for both

maternal and neonatal outcomes. For

example, it has been well-documented

that the length of labor is correlated directly with maternal chorioamnionitis,

postpartum fever, and neonatal infec-

The goal of our study was to assess the

efficacy and safety of early amniotomy in

nulliparous women who undergo labor

induction. The results of this clinical trial

indicate that early amniotomy shortens

labor by approximately 2 hours, increases the proportion of women delivered within 24 hours, but does not impact the rate of cesarean deliveries.

TABLE 2

Indications for induction

Variable

Early

amniotomy, %

Standard, %

P value

40 wk

40

39

.83

Maternal medical indication

13

14

.72

Gestational hypertension/preeclampsia

29

27

.63

.63

12

13

.63

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Intrauterine growth restriction

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Other

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Macones. Early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012.

NOVEMBER 2012 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology

403.e3

Research

Obstetrics

www.AJOG.org

TABLE 3

Maternal and labor outcomes

Outcome

Early

amniotomy

(n 292)

Standard

(n 293)

Randomization at delivery, hra

19.0 9.1

21.3 10.1

Delivery at 24 hr, %

68

56

0.72

0.590.89

.002

Cesarean delivery, %

41

40

1.03

0.850.25

.75

Amnioinfusion, %

19

19

1.02

0.731.42

.87

Chorioamnionitis, %

11.5

1.35

0.832.21

.22

Cord prolapsed, %

0.7

Abruption, %

0.4

0.6

0.55

0.056.03

.62

Postpartum hemorrhage, %

8.2

10.1

0.81

0.481.36

.44

Relative

risk

95% CI

P

value

.04

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

8.5

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

.13

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

CI, confidence interval.

a

Data are given as mean SD.

Macones. Early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012.

tion.11-13 In addition, a 2-hour difference in labor length has important implications for resource utilization at the

hospital level. For example, a 2-hour difference in time to delivery across many

inductions could lead to a decrease in

staffing of a labor and delivery unit. Last,

there is likely enhanced patient satisfaction with shorter labors as well.

The shorter duration of labor must be

weighed against both maternal and neonatal safety concerns. There were a

greater number of cases of maternal chorioamnionitis in the early amniotomy

group, although this difference was not

statistically significant. For this study,

chorioamnionitis was defined purely on

the basis of fever in labor. Given that fever is an objective measure, we do not

believe that unblinding differentially affected the ascertainment of this outcome. Importantly, this numeric difference in chorioamnionitis did not lead to

an increase in the rate of suspected neo-

natal sepsis or NICU admission, and

there were no serious maternal consequences as a result of chorioamnionitis.

Still, future studies should focus on the

occurrence of chorioamnionitis with

early amniotomy. There were also 2 cord

prolapses in the early amniotomy group

and none in the standard treatment

group. Interestingly, one of the cord prolapses occurred in a patient in the early

amniotomy group who actually was ruptured after 4 cm of dilation. Still, the occurrence of cord prolapse is concerning

and warrants further study.

Although there has been work on the

role of amniotomy in spontaneous labor,14 surprisingly, there has been little

previous work on the role of early amniotomy in the context of labor induction. There have been several clinical trials that have compared the combination

of amniotomy and oxytocin with other

methods of induction,15 but no studies

that we are aware of that focus exclu-

TABLE 4

Neonatal outcomes

Outcome

Early

Relative

amniotomy Standard risk

95% CI

P value

5-minute Apgar score

8.6

8.6

Suspected neonatal sepsis, %

9.7

11.1

0.87

0.541.41 .58

.72

Special care nursery admission, % 13.6

15.0

0.90

0.611.35 .63

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

CI, confidence interval.

Macones. Early amniotomy in nulliparous labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012.

403.e4

American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2012

sively on the timing of amniotomy in labor induction. Amniotomy has been

well-studied in the context of those

women in spontaneous labor, which included the active management of labor;

however, the work on active management of labor may not be generalized

necessarily to those women whose labor

is induced.16,17 Fraser et al10 performed a

randomized clinical trial of amniotomy

in nulliparous women in spontaneous

labor. In that study, early amniotomy reduced the occurrence of dystocia (defined as 4 hours of cervical dilation of

0.5 cm/hr) and shortened the first

stage of labor by 136 minutes. The benefit of amniotomy was greatest in women

with 3-cm initial dilation. A recent Cochrane review summarized the available

information on early amniotomy in

spontaneous labor.14 This pooled analysis did not support the notion that early

amniotomy shortened the first stage of

labor or reduced the rate of cesarean deliveries. The authors of this Cochrane review did suggest that additional research

was needed.

Our study has some notable strengths

and limitations. First, our randomization strategy effectively balanced the

study groups with respect to potentially

confounding effects and, more importantly, maximally balanced them on

unmeasured confounders. Second, the

study is relatively large in size compared

with many other studies of labor induction, which allowed us to reach an adequate sample to test our primary hypothesis. Third, we included a diverse

group of patients with various indications for induction and various methods

for induction, lending to the generalizability of the results. Last, our simple

trial design with broad inclusion/exclusion criteria and treating physician decision-making should enhance both generalizability and the translation from

efficacy in a study setting to real world

effectiveness. There are some potential

weaknesses that we believe deserve careful consideration. For practical reasons,

this study was unblinded, which could

have impacted the study results both

with the potential for unequal distribution of cointerventions and the assessment of the secondary outcomes. We

Obstetrics

www.AJOG.org

were reassured that the potential impact

of cointerventions from practitioners

because of group assignment based on

the primary outcomes were likely minimal; there were no differences between

the groups in rates of any of the induction agents that were used alone or in

combination. With regard to the secondary outcomes, it is possible that the

knowledge of treatment assignment may

have influenced our somewhat subjective newborn infant outcomes. We believe that this potential bias, if present,

would have resulted in more neonates in

the early amniotomy group being admitted to the special care nursery, thus inflating the relative risk for NICU admission. The fact that we did not observe a

difference in admissions is reassuring.

Our sample size, although sufficiently

large to test our hypothesis and compared with many studies of labor induction, was limited with respect to the confident assessment of differences in rare

outcomes, such as cord prolapse. Approximately 10% of subjects in the early

amniotomy group were ruptured after 4

cm; likewise, some women were assigned

randomly to standard treatment were

ruptured earlier. This misclassification is

likely random and would therefore likely

bias our results towards the null.

With these strengths and limitations in

mind, this study supports the following

conclusions. First, relative to standard

treatment with later amniotomy, early amniotomy shortens the time to delivery by

2 hours and increases the proportion of

induced nulliparous women who were delivered within 24 hours. Based on these

data, early amniotomy, when deemed

safe by the practitioner, may be a useful

adjunct in nulliparous labor inductions and may be incorporated into induction algorithms.

f

REFERENCES

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al.

Births: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep

2009;57:1-102.

2. Gelber S, Sciscione A. Mechanical methods

of cervical ripening and induction. Clin Obstet

Gynecol 2006;49:642-57.

3. Rayburn WF. Prostaglandin E2 gel for cervical ripening and induction of labor: a critical

analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:

529-34.

4. Hofmeyr GJ, Gulmezoglu AM. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003;1:CD000941.

5. Wing DA, Jones MM, Rahall A, Goodwin TM,

Paul RH. A comparison of misoprostol and

prostaglandin E2 gel for preinduction cervical

ripening and labor induction. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:1804-10.

6. Kelly AJ, Kavanagh J, Thomas J. Vaginal

prostaglandin (PGE2 and PGF2a) for induction

of labour at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003;4:CD003101.

7. Zhang J, Branch DW, Ramirez MM, et al.

Oxytocin regimen for labor augmentation, labor

progression and perinatal outcomes. Obstet

Gynecol 2011;118:249-56.

Research

8. Moore LE, Rayburn WF. Elective induction of

labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2006;49:698-704.

9. Luthy DA, Malmgren JA, Zingheim RW. Cesarean delivery after elective induction in nulliparous women: the physician effect. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2004;191:1511-5.

10. Fraser WD, Marcoux S, Moutquin JM,

Christen A, the Canadian Early Amniotomy

Study Group. Effect of early amniotomy on the

risk of dystocia in nulliparous women. N Engl

J Med 1993;328:1145-9.

11. Seaward PG, Hannah ME, Myhr TL, et al.

International Multicentre Term Prelabor Rupture

of Membranes Study: evaluation of predictors

of clinical chorioamnionitis and postpartum fever in patients with prelabor rupture of membranes at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;

177:1024-9.

12. Tran SH, Cheng YW, Kaimal AJ, Caughey

AB. Length of rupture of membranes in the setting of premature rupture of membranes at term

and infectious maternal morbidity. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2008;198:700.e1-5.

13. Herbst A, Kallen K. Time between membrane rupture and delivery and septicemia in

term neonates. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110:

612-8.

14. Smyth RMD, Alldred SK, Markham C. Amniotomy for shortening spontaneous labour.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

2007;4:CD006167.

15. Howarth G, Botha DJ. Amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin for induction of labour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2001;

3:CD003250.

16. Frigoletto FD, Lieberman E, Lang JM, et al.

A clinical trial of active management of labor.

N Engl J Med 1995;333:745-50.

17. Lopez-Zeno JA, Peaceman AM, Adashek

JA, Socol ML. A controlled trial of a program for

the active management of labor. N Engl J Med

1992;326:450-4.

NOVEMBER 2012 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology

403.e5

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Birth Class 11Dokumen5 halamanBirth Class 11anushkaparashar85Belum ada peringkat

- 10 1016@j Jaim 2018 08 006Dokumen7 halaman10 1016@j Jaim 2018 08 006Ega AihenaBelum ada peringkat

- Using in Children and Adolescents: BenzodiazepinesDokumen4 halamanUsing in Children and Adolescents: BenzodiazepinesEunike KaramoyBelum ada peringkat

- OPPro Psychometric PropertiesDokumen3 halamanOPPro Psychometric PropertiesShaniceBelum ada peringkat

- In-Patient: Benefit ScheduleDokumen2 halamanIn-Patient: Benefit Scheduledinda testBelum ada peringkat

- PTS I Bhs Inggris XIIDokumen7 halamanPTS I Bhs Inggris XIIVriska Budi pratiwiBelum ada peringkat

- V6 - Health CS VC Collectors 22.08.2023Dokumen92 halamanV6 - Health CS VC Collectors 22.08.2023MdnowfalBelum ada peringkat

- Turtura ResumeDokumen1 halamanTurtura ResumeaturturaBelum ada peringkat

- Is RH Factor Is Behind The Moderate Life Expectancy of Uttarakhandtribals A Brief Review 2332 0915 1000191Dokumen7 halamanIs RH Factor Is Behind The Moderate Life Expectancy of Uttarakhandtribals A Brief Review 2332 0915 1000191Mainak ChakrabortyBelum ada peringkat

- Pemilihan Kerjaya Menurut Teori HollandDokumen2 halamanPemilihan Kerjaya Menurut Teori HollandKHAIRUNISABelum ada peringkat

- Redacted Letter To Winn Correctional Center, June 10, 2021Dokumen5 halamanRedacted Letter To Winn Correctional Center, June 10, 2021Katie CrolleyBelum ada peringkat

- Nursing SeatmatrixDokumen8 halamanNursing SeatmatrixKanza KaleemBelum ada peringkat

- F3 Exam PaperDokumen20 halamanF3 Exam PaperAgnes Hui En WongBelum ada peringkat

- Natural ChildhoodDokumen28 halamanNatural Childhoodapi-205697600100% (1)

- Reinforcement Theory of MotivationDokumen10 halamanReinforcement Theory of Motivationimdad ullahBelum ada peringkat

- Tired 2. Motivated 3. Excited 4. Scared 5. Angry 6. Happy 7. Disappointed 8. Bored 9. Delighted 10.sadDokumen11 halamanTired 2. Motivated 3. Excited 4. Scared 5. Angry 6. Happy 7. Disappointed 8. Bored 9. Delighted 10.sadAnita Zarza BandaBelum ada peringkat

- TETRINDokumen2 halamanTETRINDr.2020Belum ada peringkat

- 200 PSM Questions Solved by DR AshwaniDokumen16 halaman200 PSM Questions Solved by DR AshwaniShaaron Sky SonaBelum ada peringkat

- Adherence To Medication. N Engl J Med: New England Journal of Medicine September 2005Dokumen12 halamanAdherence To Medication. N Engl J Med: New England Journal of Medicine September 2005Fernanda GilBelum ada peringkat

- Boykin & Schoenhofer's Theory of Nursing As CaringDokumen1 halamanBoykin & Schoenhofer's Theory of Nursing As CaringErickson CabassaBelum ada peringkat

- SOP For EHSSRM SystemDokumen17 halamanSOP For EHSSRM SystemMd Rafat ArefinBelum ada peringkat

- Apr W1,2Dokumen6 halamanApr W1,2Toànn ThiệnnBelum ada peringkat

- US V RodgersDokumen12 halamanUS V RodgersMelissa BoughtonBelum ada peringkat

- Asr 1Dokumen40 halamanAsr 1nadia viBelum ada peringkat

- Birla Institute of Technology & Science, Pilani Work Integrated Learning Programmes DigitalDokumen10 halamanBirla Institute of Technology & Science, Pilani Work Integrated Learning Programmes DigitalAAKBelum ada peringkat

- Cainta Catholic College Cainta, Rizal Senior High SchoolDokumen54 halamanCainta Catholic College Cainta, Rizal Senior High SchoolandyBelum ada peringkat

- Gurdjieff S Sexual Beliefs and PDokumen11 halamanGurdjieff S Sexual Beliefs and PDimitar Yotovski0% (1)

- Literature Review: Terapi Relaksasi Otot Progresif Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Pada Pasien HipertensiDokumen8 halamanLiterature Review: Terapi Relaksasi Otot Progresif Terhadap Penurunan Tekanan Darah Pada Pasien Hipertensinadia hanifaBelum ada peringkat

- INFOKIT Future ForestDokumen6 halamanINFOKIT Future ForestPOPBelum ada peringkat

- Organizing Is Good For Mental HealthDokumen2 halamanOrganizing Is Good For Mental Healthamos wabwileBelum ada peringkat