Plagues and The Crossing of The Sea - by Eakin

Diunggah oleh

Rupert84100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

103 tayangan11 halamanArticle about Exodus and the plagues and the crossing of the sea. Ancient Near Eastern exploration.

Judul Asli

Plagues and the Crossing of the Sea - by Eakin

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniArticle about Exodus and the plagues and the crossing of the sea. Ancient Near Eastern exploration.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

100%(1)100% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (1 suara)

103 tayangan11 halamanPlagues and The Crossing of The Sea - by Eakin

Diunggah oleh

Rupert84Article about Exodus and the plagues and the crossing of the sea. Ancient Near Eastern exploration.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 11

The Plagues and the Crossing of the Sea

Frank E. Eakin, Jr.

The plagues and the crossing of the sea are integral in Israel's canonical

record to the normative event in the people's history, the offering and

ratification of covenant at Mount Sinai (Ex. 24).

1

This covenant was Israel's

genesis, transforming this motley crowd into a community (Ex. 12:37-38).

Particularly during the post-exilic era, the traditions of the plagues and

the sea became pivotal. While the modern interpreter cannot unravel with

historical certainty the specific nature of these pre-covenantal events, we

may have reasonable assurance (1) that there was a sojourn of the Hebrews

in Egypt,

2

and (2) that so significant an event as the covenant experience

did not occur in isolated fashion.

The traditiohistorical character of the plague and sea traditions con-

tinues to be debated.

8

For the purposes of this study, however, we shall

focus primarily on the traditions as transmitted. Brevard Childs, who uses

historical-critical study in a most helpful fashion to enlighten the biblical

text, indicates the need for interpreting the text holistically: "It is the final

text, the composite narrative, in its present shape which the church,

following the lead of the synagogue, accepted as canonical and thus the

vehicle of revelation and instruction."

4

This plurality of happenings (Ex. 7-15) should be viewed under the

rubric of a single event.

6

Since the text canonized by the synagogue and the

church was perceived as a unit, faith's affirmation becomes the clearer when

the integrity of the text's final form is acknowledged. This approach in-

validates the modern distinction between fact and interpretation of fact.

Moshe Greenberg, a highly respected Jewish scholar, states:

Edification was the chief value of such narratives, and whatever

served to edify might fittingly be incorporated into them. The intent

was not so much to describe as to celebrate events as saving acts of

God.

e

Our focus falls upon the plagues (Ex. 7:8-11:10; 12:29-32) and the

crossing of the sea (Ex. 13:17-14:31). Prior to discussing these literary

units, however, we should clarify the Hebrew attitude toward the "mighty

act," for an understanding of the plague and sea traditions awaits

clarification of this aspect of Hebrew thought.

Hebraic Mighty Acts

In the west a mechanistic view of nature has prevailed, encouraging

confusion between the Hebraic mighty act and the Greek miracle. Greek

thought understood nature to be controlled by laws which were occasionally

abrogated, and the event occurring during this cessation and in con-

473

474

REVIEW AND EXPOSITOR

tradistinction to nature's laws was judged a miracle. To the contrary, from a

Hebraic perspective Martin Buber stated:

Miracle is not something 'supernatural' or 'superhistoricaT, but an

incident, an event which can be fully included in the objective,

scientific nexus of nature and history . . . . Miracle is simply what

happened; in so far as it meets people who are capable of receiving

it, or prepared to receive it, as miracle. The extraordinary element

favours this coming together, but it is not characteristic of it; the

normal and ordinary can also undergo a transfiguration into miracle

in the light of the suitable hour.

7

Scriptural evidence supports Buber's contention that an event need not

be extraordinary to be understood as Yahweh's mighty act. On the other

hand, Walther Eichrodt, acknowledging God's working in lesser events,

stated that "the characteristic element, as far as the worship of Yahweh was

concerned, lay in those acts of God which stood out abruptly from the

normal."

8

This statement is acceptable when set specifically against the

cultic acts and their antecedents as presented in the canonical text. Viewed

from general Hebraic lifestyle, however, Eichrodt's statement places the

emphasis excessively upon Israel's being inundated by Yahweh's power and

insufficiently upon the significance of the prophetic interpreter of the event

concernedBuber's people "capable" or "prepared" to receive the event.

One must not forget either, that ultimately the "only miracle is God him-

self "

"Miracle" is, however, an inappropriate word to use with Hebraic

thought, for no word in the Masoretic text properly translates as "miracle."

The Hebrew spoke instead of Yahweh's mighty works, his "signs" and

"wonders."

10

The sign C oth) points beyond itself to something of greater

significance, "a visible evidence of the presence and purpose of God."

u

For

example, it is stated in Exodus 3:12 that the Hebrews' arrival at Mount

Sinai will be a sign of Yahweh's activity in their behalf. Wonder (mopheth)

designates events of a more stupendous nature. For example, in Exodus 7:9

the rod's being transformed into a serpent is the wonder (translated as

"miracle" in RSV).

Several interpretive principles should be acknowledged, therefore, when

interpreting the mighty act. First, the significance of an event rests in the

understanding of that event on the part of the beholder /interpreter, i.e., the

revelatory event is what the individual understands it to be. Second, Yah-

weh is always primarily understood as a God of history, not of nature, and

whatever events of nature he utilized as the vehicle of his revelation are

always thoroughly stamped with the imprint of historical awareness.

18

Third,

because Yahweh's mighty acts refer to historical occurrences rather than to

suprahistorical or to contra- and/or intranatural law events, understanding

of the mighty act correlates with the relation of the event to concrete

historical data. This does not negate the fact, however, that a commingling

of the "wonderful and ordinary" will characterize the mighty act. ". Nor does

acknowledgment of these principles deny the activity of power of God; to the

contrary, they simply affirm the recognition of that activity and power

within the parameters of the Hebrew mind.

THE PLAGUES AND THE CROSSING OF THE SEA 476

The Plagues

(7:8-11:10; 12:29-32)

The plagues are simultaneously enigmatic and illuminatingenigmatic

in that assured historicity eludes the interpreter, illuminating as conveyors

of Hebrew thought. The developed tradition dramatically

14

and didactically

affirmed in creedal-like fashion the historical power (not magic

16

) of Yahweh,

the God of deliverance.

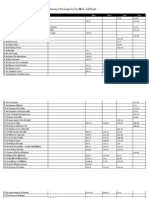

The plagues are developed in the following sequence:

Plague Sequence Reference

1. Water turned red Exodus 7:14-24

2. Frogs Exodus 7:25-6:15

3. Gnats Exodus 8:16-19

4. Flies Exodus 8:20-32

5. Cattle Exodus 9:1-7

6. Boils Exodus 9:8-12

7. Hau Exodus 9:13-35

8. Locusts Exodus 10:1-20

9. Darkness Exodus 10:21-29

10. Death of first-born Exodus 11:1-10; 12:29-32

It has been suggested tnat the plagues are arranged in three cycles of

three plagues each, culminating with the single plague, the death of the

first-born:

1

First Cycle Second Cycle Third Cycle

1. Water turned red 4. Flies 7. Ha

2. Frogs 5. Cattle 8. Locusts

3. Gnats 6, Bos 9. Darkness

In each cycle, Moses issued a warning prior to the first two plagues. In the

first plague of each cycle, Moses was commanded by Yahweh to come before

Pharaoh in the morning to give warning. Yahweh also told Moses to warn

Pharaoh before the second plague of each cycle, but the time for doing so

was not specified. The third plague occurred each time without warning.

17

Typically, the third-cycle plagues were harsher than those of the first two

cycles.

Three pentateuchal sourcesJ, E, and P record the plague

tradition.

18

No single source, however, records all ten plagues.

19

To develop

the canonical text, therefore, the three sources were gradually united. Some

relevant data regarding the sources are presented below:

Source Data Yahwist Elohist Priestly

Date 950 B.C. 850-750 B.C 550-450 B.C.

Provenance Judah Israel Babylonia/Jerusalem

Literary Responsibility Yahwist(?) Elohist(?) Yahwistic Priests

Executor of Act Yahweh Moses Aaron

The following chart indicates the plagues presented in each source:

10

Plague Description Yahwist Elohist Priestly

1. Water turned red X X X

2. Frogs X X

476 REVIEW AND EXPOSITOR

3. Gnats

4. Flies X

5. Cattle X

6. Boils

7. Hau X X

8. Locusts X X

9. Darkness X

10. Death of first-born X X

Perhaps some plagues are duplicate accounts of differently transmitted

traditions.

91

For example, the Yahwist's rendering of the plagues involving

the flies (8:20-32, number 4) and the cattle (9:1-7, number 5) is possibly

duplicated by the Priestly account of the plagues involving the gnats

(8:16-19, number 3) and the boils (9:8-12, number 6). " While dogmatism is

inappropriate on the question of duplications, one can be assured that the

present ten-plague literary construction found in the text is an artificial one.

The Passover tradition assumed a pivotal position in Israelite worship,

and it would be generally acknowledged that his periscope circulated as a

separate tradition among the early Israelites. From the perspective of the

canonized tradition, however, one should not divorce the internal integrity of

the plagues and the Passover.

28

In Jewish tradition, the "signs and won-

ders" rehearsed refer primarily to the plagues

According to Jewish understanding, Exodus 20:2 ("I am the LORD

your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of

bondage") constitutes the first commandment.

24

The more traditional

Christian position has been that Exodus 20:2 is an "introductory formula"

rather than the first commandment.

26

If the importance of acknowledging

the deity responsible for bringing the Hebrews "out of the land of Egypt" be

recognized, the pivotal nature of the "signs and wonders" takes clearer

focus. On the basis of these pre-Sinaitic events, a covenant was offered,

accepted, and ratified.

Obviously the traditional importance attached to the plagues does not

eliminate the problems associated with them, as is indicated for example by

the often noted silence regarding the plagues in Egyptian literature. Behind

this concern is the presumption that, had something so striking as that in-

dicated in the biblical text occurred, th Egyptians would have recorded it.

This issue is not valid, however, for it treats the biblical text as a modern

historical document. The ancient directed greater interest to the meaning of an

event than to the event itself. The ancient Israelite's interest rested in the con-

test waged between Yahweh and the Pharaoh (as well as with the other gods of

Egypt). Not one of the gods of Egypt could thwart the designs of Yahweh, and

this was the point the transmitted traditions sought to convey.

Since the meaning behind the event was more central than the

descriptive details of the event, it is unwise to seek an historical recon-

struction of the plagues on the basis of available evidence.

se

Childs, in-

dicating his concern about such attempts, notes that "in the end, this genre

THE PLAGUES AND THE CROSSING OF THE SEA 477

of apologetic literature suffers from the strange anomaly of defending biblical

'supernaturalism' on the grounds of rationalistic arguments."

1T

Although these events are rooted in observable history (i.e., they were

concrete events, albeit not "verifiable" by historical-critical tools), one must

not fall prey to the modernist temptation to reconstruct them with an in-

dubitable specificity. The evidence needed to do so is unavailable today.

What is crucial to interpretation is that, through the vehicle of this holistic

narrative, the Hebrews have proclaimed that God has acted.

The plague narrative is pivotal in the biblical text, not because it gives the

interpreter an historical slice of ancient Egyptian life but because it portrays

early Israel's affirmations regarding Yahweh. This Yahweh is

the Lord of history who acts in judgment upon those who at-

tempt to thwart the administration of justice;

the God of freedom who demands that his creation live in and

propagate the cause of freedom; and

the God of deliverance who acts to deliver his elect from

Egyptian oppression, thereby giving assurance of his commitment to

be constant in his vigil to deliver them from any individual, people,

or situation which would prevent their absolute affirmation that

"Yahweh, he is God!"

The plague narrative, therefore, was Israel's mode of doing theology,

You know Yahweh concretely by what he does, not abstractly by con-

templating what is he!

The Crossing of the Sea

(13:17-14:31)

The tradition of the sea's crossing has long been problematic for in-

terpreters," and numerous scholars have attempted to clarify the sea

event.*

9

Nonetheless, Israel perceived this to be Yahweh's pivotal act.

Rylaarsdam captured the event's importance: "The event is for the O.T.

what Jesus as Christ is to the N.T.the normative redeeming and revealing

act of God."

20

Regardless of critical issues,

81

the sea event as a basic and

traditional foundation stone for Israelite faith must be kept in focus.

The geographic site of the sea's crossing is unknown.

82

Perhaps the only

certainty is that the Red Sea was not intended. If the Hebrews dwelled in

Goshen in the Nile Delta, the distance from Goshen to the Red Sea would

make impossible the Hebrews' fleeing successfully on toot from the

Egyptians using chariots. In addition, the Hebrew designation does not

support "Red Sea."

The Hebrew yam suph should be translated as "reed sea" or "sea of

reeds." This term is a generic description rather than a proper name. When

the Hebrew text was translated into Greek (Septuagint), yam suph was

translated as eruthra thalassa ("Red Sea," see Ex. 13:18). Since early

English translators were more dependent upon Greek than Hebrew, tue

Septuagintal translation found its way into English texts and was trans-

mitted. In 1962 an English edition of The Torah (The Jewish Publication

Society of America) properly translated yam suph as "Sea of Reeds."

478

REVIEW AND EXPOSITOR

Considerable confusion would be avoided if other translations would do

likewise.

Exodus 14 demonstrates a layered effect, an apparent developmental

process as traditions were combined. In the J materials, God drove back the

water by an east wind, permitting the Hebrews to cross safely. The E

narrative portrays Moses' rod to be, necessary to the water's disap-

pearancea type of magical aura pervades the scene. With the process

was completed as the water not only recedes for the Hebrews' crossing, but

it also pulls back like walls on either side!

When the J source

88

and the Miriam couplet (Ex. 15:21") are jux-

taposed, a probable event unfolds. The Hebrews fleeing Egypt were pursued

by the Egyptians using chariots. When the Hebrews confronted a shallow

body of water, a strong east wind blew back the water in a reedy, shallow

area, permitting the Hebrews to cross. When the Egyptians sought to

follow, their chariots were too heavy and bogged down. As the horses at-

tempted to pull free, some of the Egyptians were thrown into the shallow

water and mud. In the confusion some Egyptians died.

The important fact, however, is that the ancient Israelites who

remembered and transmitted this story knew only divine causation. This

event was no fluke. Their emancipation from Egyptian bondage was the act

of Yahweh. He had delivered! He had made freedom possible. As G. Henton

Davies noted: "The Israelites believed they had seen, and had been saved

by, a great miracle which was to become one of the themes of their story and

worship in perpetuity."

86

Nonetheless, the event as transmitted does have a unity of its own;

86

and it is important for the interpreter to see the event in its wholeness as

well as in its parts.

87

Through this unity Israel's faith affirmed that this

event was Yahweh's act. We must acknowledge the passage holistically to

understand its meaning for the community of faith, and this exercise must

precede the dissection of the narrative into its component sources.

The literary composition of the present material should be understood,

however, and the rationale for a tradition's compositional enlargement

should be sought. The most reasonable response lies in Yahwism's encounter

wit Baalism,

88

for the primary motif needing clarification is the heightening

of the water-separation element.

In Baalistic mythology, one theme revolved around Baal's encounter

with Yam, the chaotic water god whom Baal must conquer before his

authority will be recognized.

88

Ultimately Baal's victory was acclaimed; and

he became the chief god in worship, even though El continued to mpinfann

titular kingship.

The Israelites having entered Canaan (thirteenth century), if Yahweh

were to retain his dominant role, then the view of Yahweh must alter suf-

ficiently that tose agrarian functions fulfilled by the Canaanite deities

would be assumed by Yahweh. This is a brief statement of an exceedingly

complex cultural struggle which engaged the Israelites for centuries;

nevertheless, the end result was biblical Yahwism, a type of Hegelian

THE PLAGUES AND THE CROSSING OF THE SEA 4TO

eyntheeis derived from the amalgation of Israelite Mosaic faith and

Canaanite Baalism.

40

In the procees of this cultural struggle and amalgamation, thmes

associated with Baalism were absorbed into Yahwism. Yahweh, not Baal,

was the one to do struggle with the chaotic watery elements.

41

Yahweh, not

Baal, was the victorious God!

The process by which this assimilation took place I have argued

elsewhere. Suffice at this point to indicate that it could have occurred via

northern sources where Baalism traditionally posed the greater threat to

Yahwism,

48

by post-exilic priestly hands when monotheism prevailed and

thus rendered moot associations with other deities, or through actual en-

counter with and absorption of Baalistic elements while in Egypt or at least

in the departure process.

48

Historical certitude will forever elude the investigator of the sea event.

The historian recognizee that this event has been both transmitted and

transformed, covered over and filled with both myth and legend. With

typical insight, James Muilenburg stated:

If one is tempted to raise the legitimate and necessary question,

what was it that happened at the Sea of Reeds? then there is the

equivocal answer that the historian is forced to give because he really

does not know. There is also the answer that faith gives: "Our God

delivered us from bondage."

44

It is this answer of faith upon which this article has focused, for whatever

the critical analysis the voice of faith was always dear, "Yahweh lias

delivered!" It is this assured response by the faithful that shaped the faith

community.

Conclusion

The plague and sea crossing traditions were recorded to be didactic and

to facilitate existential encounter of the reader/hearer with Yahwh, the God

responsible for the events. History as the chronicle of verifiable events was

not the concern of these writers/redactors. Greenberg properly suggests:

"The reality that the tale intends to convey is not past historical but present

affective: the experience of events as they were taken in first by eyewit-

nesses, then through the consciousness of the generations who perennially

relived and reflected on them as, the basis of their own living faith*"

41

This

series of events, beginning with the theophany to Moses at the bush (Ex. 3)

and concluding with the covenant's ratification (Ex. 24), became the

normative guide for Israel's relationship to God as well as her relationship to

her neighbors.

For the biblical critic's task, it is important to understand the

relationship of the parts (plague narrative, Passover tradition, the encounter

with the sea, and the hymnic versions of Ex. 15), how the sources developed

ami ultimately came together, and how the component parts relate not only

to each other but to their larger context as well. Nonetheless, while not

demeaning at all these critical issues, it is also important to view the

tradition holistically, to see it in the integrity of its unity as it would

480 REVIEW AND EXPOSITOR

have been cultkally rehearsed, at least after the Torah became canonically

fixed.

When so perceived, the material assumes additional dimensions of

significance. We see both Israel's confession and the understood base for

that confession. We see a people of history who ground their conviction in

the inexorable assurance of Yahweh, the God of history, the assurance which

made this tradition believable. Significantly, in The Pentateuch and Haf-

torahs, we are reminded:

In the Haggadah shel Pesach, the story of the Redemption is told

without any reference to the Leader. Once only, indirectly in a

quotation, does the name Moses occur at all in the whole Seder

Service

48

A passage in Deuteronomy, judged by Gerhard von Rad to be perhaps the

oldest creedal affirmation in the Hebrew scriptures,

47

states appropriately

our conclusion:

. . . the Egyptians treated us hardily, and afflicted us, and laid upon

us hard bondage. Then we cried to the LORD the God of our fathers,

and the LORD heard our voice, and saw our affliction, our toil, and

our oppression; and the LORD brought us out of Egypt with a

mighty hand and an outstretched arm, with great terror, with signs

and wonders . . . (Deut. 26:6-8).

48

1

See George E. Mendenhall, Law and Covenant in Israel and the Ancient Near East

(Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Biblical Colkxjuim, 1966), and "Covenant." The Inter-

preter's Dictionary of the Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Pnee, 1962), 1:714-723. From Dennis J.

McCarthy, see Treaty and Covenant (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1968), and Old

Testament Covenant, "Growing Pointa in Theology" (Richmond, Virginia: John Knox Presi,

1972). See also Klaue Baltser, The Covenant Formulary, trans. David E. Green (Philadelphia:

Fortress Press, 1971).

Cf. Martin Noth, The History of Israel, 2nd ed., trans. P. R. Ackroyd (New York:

Harper * Row, Publishers, I960), pp. 110-121; and John Bright, A History of Israel, 2nd ed.

(Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1972), pp. 103-139. Moshe Greenberg, in Under-

standing Exodus, "The Heritage of Biblical Israel" (New York, N. Y.: Behrman House, Inc.,

1969), p. 204, states: "The gross features of the Exodus story . . . are too unflattering to have

been late inventions, and have enough (through meager) contacts with extrabiblfcal evidence to

be creditable . . . what merge is not history but Israel's celebration of its history as the

saving sets of God."

Cf. Martin Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, trans. J. S. Bowden, 'Old Testament

library" (Philadelphia: The Westminster Prese, 1962), p. 106; and Dennis J. McCarthy,

'Moses' Dealings with Pharaoh: Exodus 7:8-10:27," Catholic Biblical Quarterly, 27:336-347,

October 1966; aleo by McCarthy, "Plagues and the Sea of Reeds: Exodus 6-14," Journal of

Biblical Literature, 86:137-168, June, 1966.

4

Brevard S. Childs, The Booh of Exodus, "The Old Testament Library" (Philadelphia:

The Westminster Press, 1974), p. xv.

1

See the author's The Religion and Culture of Israel (Washington, D. C: University

Press of America, 1977), pp. 61-76.

* Greenberg, Understanding Exodus, p. 193.

' Martin Beber, Moses (New York: Harper Torchbooke, 1968), p. 76.

Weither Eichrodt, Theology of the Old Testament, trans. J. A. Baker, "The Old

Testament Library" (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1961), 1:463.

9

Edmond Jacob, Theology of the Old Testament, trans. A. W. Heethcote and P. J.

AUcock (New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1968), p. 223.

THE PLAGUES AND THE CROSSING OF THE SEA 481

10

Two helpful articles are James B. Pritchard, "Motifs of Old Testament Miracles," Crozer

Quarterly, 27:97-109, April, 1960; and Harold Knight, "The Old Testament Conception of

Miracle," Scottish Journal of Theology, 5:355-361, December, 1952.

11

Bernhard W. Anderson, Understanding the Old Testament, 3rd ed. (Englewood Cliffs,

New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1975), p. 65.

11

See Buber, Moses, pp. 78-79.

18

Childs, The Book of Exodus, p. 238.

14

G. Henton Davies, Exodus, "Torch Bible Commentaries" (London: SCM Press, Ltd.,

1967), p. 90, who suggested dramatic presentation of the tradition at Passover.

16

Greenberg, Understanding Exodus, p. 169. U. Caseuto, in A Commentary on the Book

of Exodus, trans. Israel Abrahams (Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 1967), states that "the

Torah is absolutely opposed to all forms of magic . . . " (p. 95).

1

See J. H. Hertz, ed., The Pentateuch and Haftorahs, 2nd ed. (London: Sonano Press,

1970). p. 400.

17

Cas su to, A Commentary on the Book of Exodus, pp. 92-93.

18

S. R. Driver, The Book of Exodus, rev. ed., "The Cambridge Bible for Schools and

Colleges" (Cambridge: University Press, 1953), 111:55, succinctly stated that the differences

relative to the literary sources "Relate to not less than five or six distinct points,the terms

of the command addressed to Moses, the part taken by Aaron, the demand made of the

Pharaoh, for the use made of the rod, the description of the plague, and the formulae used to

express the Pharaoh's obstinacy." See also Buber, Moses, pp. 62ff., regarding expansion of

the plague tradition during the Elisha period.

19

The division used in this presentation accords with that of J. Coert Kylaarsdam, "The

Book of Exodus," The Interpreter's Bible (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1952), 1:838-839,

895-915, and 924-925. See also Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, pp. 62-99; and Childs, The

Book of Exodus, pp. 130-141. Cf. Greenberg, Understanding Exodus, pp. 183-192.

20

Because scholars differ so in their assignments of verses to the separate sources, a

source analysis would not be particularly beneficial for the interests of this article. The reader

seeking information on analysis is encouraged to look especially at the appropriate sections in

Childs, The Book of Exodus; Noth, Exodus, A Commentary; and Rylaarsdam, IB, I.

21

See J. Philip Hyatt, Commentary on Exodus, "New Century Bible" (Greenwood, S. C:

The Attic Press, Inc., 1971), pp. 96-139, on plagues.

" See Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, p. 76; and Rylaarsdam, IB, 1:838.

28

Cf. Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, pp. 68-69.

24

See Yehezkel Kaufmann, The Religion of Israel, trans, and abridged by Moshe

Greenberg (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1960), p. 132; and Hertz, ed., The

Pentateuch and Haftorahs, 2nd ed., p. 295. See also the helpful chart prepared by B. Davie

Napier, "The Book of Exodus," The Layman's Bible Commentary (Richmond: John Knox

Press, 1963), 111:75.

" Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, p. 161. Hyatt, Commentary on Exodus, p. 210, agrees.

" See Greta Hort, "The Plagues of Egypt," Zeitschrift fr die alttestamentUche

Wissenschaft, 69:84-103, 1957; or Jack Finegan, Let My People Go (New York: Harper and

Row, 1963).

27

Childs, The Book of Exodus, p. 168. See also Greenberg, Understanding Exodus, p.

202.

98

The author's view may be found in The Religion and Culture of Israel, pp. 60-67, and

"The Reed Sea and Baalism," Journal of Biblical Literature, 86:378-384, December, 1967.

29

Cf. Lewis S. Hay, "What Really Happened at the Sea of Reeds?" Journal of Biblical

Literature, 83:397-403, December, 1964; George W. Coats, "The Traditio-Historical Character

of the Reed Sea Motif," Vetus Testamentum, 17:253-265, July, 1967; Brevard S. Childs, "A

Traditio-Historical Study of the Reed Sea Tradition," Vetus Testamentum, 20:406-418,

October, 1970; and Dale Patrick, "Traditio-History of the Reed Sea Account," Vetus

Testamentum, 26:248-249, April, 1976. See also Childs, The Book of Exodus, pp. 215,

223-224; and Hyatt, Commentary on Exodus, pp. 156-161.

80

Rylaarsdam, IB, 1:935.

81

Frank Michaeli, Le Livre de LExode, "Commentaire de L'Ancien Testament" (Paris:

Delachaux & Niestle, 1974), p. 128.

482

REVIEW AND EXPOSITOR

82

Sites varying from the northern Gulf of Suez (or an inland extension thereof), an inland

body of water such as Lake Timsah, the western shores of the Sirbonian Sea, or the northern

tip of the Gulf of Aqabah have been suggested.

88

See analyses of x. 14 by Childs, The Book of Exodus, pp. 218-221; Noth, Exodus, A

Commentary, pp. 102-126; and Rylaarsdam, IB, 1:932-939.

84

Noth, Exodus, A Commentary, pp. 121-122. Noth judges chapter 15 to be relatively

late, although he accepts verse 21 as the oldest part of the chapter. F. M. Cross, Jr., and

David N. Freedman, "The Song of Miriam," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 14:237-260,

October, 1955; and F. M. Cross, Jr., "The Song of the Sea and Canaanite Myth," God and

Christ: Existence and Province, ed. R. W. Funk, et al., Journal for Theology and the Church

(New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1968), 5:1-25, have argued for the early dating of

chapter 15. Buber, Moses, p. 74, states that "A song dating back to the time of Moses is

preserved in Exodus xv, 21."

88

Davies, Exodus, p. 124. See also Leandre Boisvert, "Le Passage de la Mer des Roseaux

et la Foi d' Israel," Science et Esprit, 27:147-159, May-September, 1975.

88

See Hyatt, Commentary on Exodus, pp. 148-149.

87

See Childs, The Book of Exodus, pp. 227-228.

88

See footnote 28 for author's position. See also Childs, The Book of Exodus, p. 223.

88

The Ugaritic texts do not recount this struggle in full. See G. R. Driver, Canaanite

Myths and Legends, "Old Testament Studies" (Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark, 1956), III, 13-14,

80-83.

40

See The Religion and Culture of Israel, pp. 198-223.

41

Genesis 1:6-10 and Psalm 74:13-14. See T. H. Gaster, Thespis (New York: Harper

Torchbooks, 1966), pp. 142-148, for suggestions of passages from which the biblical myth may

be pieced together.

42

Georg Beer, "Exodus," Handbuch zum Alten Testament, ed. Otto Eissfeldt (Tubingen:

J. C. . Mohr, 1939), III, 12.

48

The Baal-zephon reference of Ex. 14:2 apparently referred to a Baal sanctuary. See Otto

Eissfeldt, Baal Zaphon, Zeus Kasios und der Durchzug der Israeliten durch Meer (Halle

[Saale]: Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1932). Supported by Noel Aime'-Giron, "Ba

/

al Saphon et les

Dieux de Tahpanhes dans un Nouveau Papyrus Phnicien," Annales Du Service Des

Antiquits De L'Egypt, 40:433-460, 1941.

44

James Muilenburg, The Way of Israel (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1966), p. 49.

48

Greenberg, Understanding Exodus, p. 204.

48

Hertz, ed., The Pentateuch and Haftorahs, 2nd ed., p. 270.

47

Gerhard von Rad, Old Testament Theology, trans. D. M. G. Stalker (New York:

Harper & Row Publishers, Inc., 1962), 1:122.

48

In light of the earlier discussion regarding the post-exilic priestly absorption of Baalistk

motifs, it is noteworthy that Deuteronomy 26 may be read without reference to the sea event.

The "signs and wonders" may refer only to the plague tradition. In Nehemiah 9:6-31, a post-

exilic creedal statement, however, the sea event is explicitly noted: "And thou didst see the

affliction of our fathers in Egypt and hear their cry at the Red Sea . . . And thou didst divide

the sea before them, so that they went through the midst of the sea on dry land; and thou

didst cast their pursuers into the depths, as a stone into mighty waters" (Neh. 9:9, 11).

Further discussion of this would take us too far afield, but the implications of this develop-

ment should be considered by the reader as regards the dynamic character of Israel's faith.

^ s

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use

according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as

otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.

No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the

copyright holder(s)' express written permission. Any use, decompiling,

reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a

violation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission

from the copyright holder(s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of a journal

typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However,

for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article.

Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific

work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered

by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the

copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available,

or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s).

About ATLAS:

The ATLA Serials (ATLAS) collection contains electronic versions of previously

published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS

collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association

(ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc.

The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American

Theological Library Association.

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- BC ExodusDokumen209 halamanBC ExodusSilas ChavesBelum ada peringkat

- MK 11 - A Triple IntercalationDokumen13 halamanMK 11 - A Triple Intercalation31songofjoyBelum ada peringkat

- Libro de Texto - Hasel OTDokumen97 halamanLibro de Texto - Hasel OTRichard Adams100% (2)

- Frank S. Frick The City in Ancient Israel 1977Dokumen148 halamanFrank S. Frick The City in Ancient Israel 1977BLINDED185231100% (1)

- A Feminist Companion To The Catholic EpiDokumen15 halamanA Feminist Companion To The Catholic EpiMichael CheungBelum ada peringkat

- Ibn Ezra On Exodus - English Translation - PlainDokumen33 halamanIbn Ezra On Exodus - English Translation - PlainhhkkkkjjBelum ada peringkat

- Creation in Hebrews: Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 53, No. 2, 279-320Dokumen42 halamanCreation in Hebrews: Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 53, No. 2, 279-320Oscar Mendoza OrbegosoBelum ada peringkat

- Exodus LessonDokumen307 halamanExodus LessonDaryl BadajosBelum ada peringkat

- Prayers of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, and WritingsDari EverandPrayers of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry, and WritingsBelum ada peringkat

- DOUGLAS - Justice As The CornerstoneDokumen10 halamanDOUGLAS - Justice As The CornerstoneLuciano CoutoBelum ada peringkat

- Commentary On Genesis 12,1-4a.claasensDokumen3 halamanCommentary On Genesis 12,1-4a.claasensgcr1974100% (1)

- Notes On Ezekiel-W KellyDokumen126 halamanNotes On Ezekiel-W Kellycarlos sumarchBelum ada peringkat

- Genesis 4.7 - What Does God Say To CainDokumen20 halamanGenesis 4.7 - What Does God Say To Cainbdudgeon85100% (1)

- Studying The Bible - The Tanakh and Early Christian WritingsDokumen191 halamanStudying The Bible - The Tanakh and Early Christian WritingsEmilyBelum ada peringkat

- Proverbs Bibliography AnnotatedDokumen28 halamanProverbs Bibliography Annotatedpsalm98docBelum ada peringkat

- 02 - Exodus PDFDokumen219 halaman02 - Exodus PDFGuZsolBelum ada peringkat

- The Book of IsaiahDokumen59 halamanThe Book of IsaiahSirish Chand PutlaBelum ada peringkat

- Ben ZakaiDokumen17 halamanBen ZakaiChicho Follón100% (1)

- Hebrews1.6 - Souce and SignificanceDokumen14 halamanHebrews1.6 - Souce and Significance31songofjoyBelum ada peringkat

- The Meaning of Justice and RighteousnessDokumen2 halamanThe Meaning of Justice and Righteousnessapi-3805656Belum ada peringkat

- Theodicy of JobDokumen6 halamanTheodicy of JobPietro_Pantala_8703Belum ada peringkat

- A Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and The Creation of American Protestantism.Dokumen50 halamanA Mighty Baptism: Race, Gender, and The Creation of American Protestantism.Fernanda CarvalhoBelum ada peringkat

- Nathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureDokumen272 halamanNathan Still Schumer, The Memory of The Temple in Palestinian Rabbinic LiteratureBibliotheca midrasicotargumicaneotestamentariaBelum ada peringkat

- A Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingDokumen7 halamanA Study Into The Meaning of The Work GENTILE As Used in The Bible by Pastor Curtis Clair EwingbadhabitBelum ada peringkat

- ExodusDokumen177 halamanExodusToJo Reyes100% (1)

- F.F. Bruce - and The Earth Was Without Form and Void, An Enquiry Into The Exact Meaning of Genesis 1, 2Dokumen5 halamanF.F. Bruce - and The Earth Was Without Form and Void, An Enquiry Into The Exact Meaning of Genesis 1, 2Donald LeonBelum ada peringkat

- The Use of Hagios For The Sanctuary in The Old Testament PseudepiDokumen13 halamanThe Use of Hagios For The Sanctuary in The Old Testament PseudepiMaicol Alejandro Cortes PinoBelum ada peringkat

- Harmony of The Gospels by Troy Welch Todd BoundDokumen9 halamanHarmony of The Gospels by Troy Welch Todd BoundskylerzhangBelum ada peringkat

- 23 - Isaiah PDFDokumen357 halaman23 - Isaiah PDFGuZsol100% (2)

- Commentary To The Book of Hosea - Rev. John SchultzDokumen78 halamanCommentary To The Book of Hosea - Rev. John Schultz300r100% (1)

- Daniel: A Commentary, by Carol A. Newsom. Westminster John Knox PressDokumen4 halamanDaniel: A Commentary, by Carol A. Newsom. Westminster John Knox PressJim West0% (1)

- On The Road To Mt. SinaiDokumen27 halamanOn The Road To Mt. SinaiBill Creasy100% (1)

- Peshat and ExegesisDokumen13 halamanPeshat and Exegesisraubn111Belum ada peringkat

- Ollenburger - Isaiah's Creation TheologyDokumen19 halamanOllenburger - Isaiah's Creation Theologykansas07Belum ada peringkat

- Exegesis of Deuteronomy 30-1-4Dokumen33 halamanExegesis of Deuteronomy 30-1-4Augustine RobertBelum ada peringkat

- 6 - JoshuaDokumen82 halaman6 - JoshuaAmir SamyBelum ada peringkat

- A Controversial Spirit - Evangelical Awakenings in The SouthDokumen245 halamanA Controversial Spirit - Evangelical Awakenings in The SouthTip Our Trip100% (1)

- Goldingay - Teología BíblicaDokumen26 halamanGoldingay - Teología BíblicaAlberto PérezBelum ada peringkat

- Koet Umbruch Korr04Versand20181206BJK PDFDokumen327 halamanKoet Umbruch Korr04Versand20181206BJK PDFMarko MarinaBelum ada peringkat

- JOSHUAS OF HEBREWS 3 AND 4 Bryan J WhitfieldDokumen16 halamanJOSHUAS OF HEBREWS 3 AND 4 Bryan J WhitfieldRichard Mayer Macedo SierraBelum ada peringkat

- The Golden CalfDokumen26 halamanThe Golden CalfBill Creasy100% (1)

- Nahum M. Sarna - Nahum N. Sarna - Understanding Genesis-Heritage of Biblical IsraelDokumen309 halamanNahum M. Sarna - Nahum N. Sarna - Understanding Genesis-Heritage of Biblical IsraelBorna JurasBelum ada peringkat

- Martinus de Boer - Ten Thousand Talents - Matthew's Interpretation & Redaction of The Parable of Unforgiving Servant (Mt. 18 23-35 1988)Dokumen20 halamanMartinus de Boer - Ten Thousand Talents - Matthew's Interpretation & Redaction of The Parable of Unforgiving Servant (Mt. 18 23-35 1988)madsleepwalker08Belum ada peringkat

- Essay Hellenized JewsDokumen7 halamanEssay Hellenized JewsDaniel BellBelum ada peringkat

- Stephen Baba - Mission in MalachiDokumen14 halamanStephen Baba - Mission in MalachiMorris SupitBelum ada peringkat

- Kartveit, Theories of Origin of Samaritans (2019)Dokumen14 halamanKartveit, Theories of Origin of Samaritans (2019)Keith Hurt100% (1)

- Johannine Ecclesiology - The Community's OriginsDokumen15 halamanJohannine Ecclesiology - The Community's OriginsJoeMoellerBelum ada peringkat

- Pastoral and General Epistles Exegetical PaperDokumen17 halamanPastoral and General Epistles Exegetical PaperPhillip BozarthBelum ada peringkat

- Samaritan Update Vol XVIIDokumen122 halamanSamaritan Update Vol XVIIyohannpintoBelum ada peringkat

- Literary Analysis On Ecclesiastes 10Dokumen4 halamanLiterary Analysis On Ecclesiastes 10pplthinkimcoolBelum ada peringkat

- Commentary On Isaiah 40 55Dokumen18 halamanCommentary On Isaiah 40 55milikheor kasa100% (2)

- Women's Crucial but Overlooked Roles in Early ChristianityDokumen7 halamanWomen's Crucial but Overlooked Roles in Early ChristianityAllen Rangla KharamBelum ada peringkat

- 00 Cover Intro Index PrefacesDokumen16 halaman00 Cover Intro Index Prefacespieterinpretoria391Belum ada peringkat

- Ezekiel PDFDokumen387 halamanEzekiel PDFMcdonalds NakaBelum ada peringkat

- Controversial Distinction in Jesus TeachingDokumen23 halamanControversial Distinction in Jesus Teaching31songofjoyBelum ada peringkat

- The Old Testament and The Messianic HopeDokumen10 halamanThe Old Testament and The Messianic HopedlaleBelum ada peringkat

- Up From Sea and Earth - Revelation 13 - 1 11 in ContextDokumen363 halamanUp From Sea and Earth - Revelation 13 - 1 11 in ContextIustina și ClaudiuBelum ada peringkat

- Caesar's Pre-Battle SpeechDokumen10 halamanCaesar's Pre-Battle SpeechAngela Leong Feng PingBelum ada peringkat

- The Resurrection in Romans PrintDokumen16 halamanThe Resurrection in Romans PrintKim J AlexanderBelum ada peringkat

- Houtman - The Urim and ThummimDokumen5 halamanHoutman - The Urim and ThummimRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Ben-Tor - The Scarab - BibliographyDokumen4 halamanBen-Tor - The Scarab - BibliographyRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Betlyon, John - A People Transformed - Palestine in The Persian PeriodDokumen56 halamanBetlyon, John - A People Transformed - Palestine in The Persian PeriodRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Babylonian Divinatory Text - Intro Only - CUSAS-18-FrontalDokumen28 halamanBabylonian Divinatory Text - Intro Only - CUSAS-18-FrontalRupert84100% (1)

- Wright Study of Ritual in The Hebrew Bible-LibreDokumen21 halamanWright Study of Ritual in The Hebrew Bible-LibreRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Applegate - Zoroastrianism - Lit ReviewDokumen14 halamanApplegate - Zoroastrianism - Lit ReviewRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- SBL Section 7Dokumen11 halamanSBL Section 7Rupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Archaeological Sources For The History of Palestine - Late Bronze AgeDokumen37 halamanArchaeological Sources For The History of Palestine - Late Bronze AgeRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Arnow, David - The Passover Haggadah - Moses and The Human Role in RedemptionDokumen26 halamanArnow, David - The Passover Haggadah - Moses and The Human Role in RedemptionRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Are The Ephod and The Teraphim Mentioned in Ugaritic Lit - by AlbrightDokumen5 halamanAre The Ephod and The Teraphim Mentioned in Ugaritic Lit - by AlbrightRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- SBL Section 7Dokumen11 halamanSBL Section 7Rupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Jenkins, A. K. - Hezekiah's Fourteenth YearDokumen16 halamanJenkins, A. K. - Hezekiah's Fourteenth YearRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Aberle, David F. - Religio-Magical Phenomena and Power, Prediction and ControlDokumen11 halamanAberle, David F. - Religio-Magical Phenomena and Power, Prediction and ControlRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- S BL Volume Editor GuidelinesDokumen11 halamanS BL Volume Editor GuidelinesRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Biblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualDokumen13 halamanBiblical Hebrew (SIL) ManualcamaziBelum ada peringkat

- Bibliography From Ancient Mesopotamian Religion - by Tammi J SchneiderDokumen9 halamanBibliography From Ancient Mesopotamian Religion - by Tammi J SchneiderRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Vanderram, James C. - Mantic Wisdom in The Dead Sea ScrollsDokumen19 halamanVanderram, James C. - Mantic Wisdom in The Dead Sea ScrollsRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- The Coregency of Ramses II With Seti I and The Date of The Great Hypostyle Hall at KarnakDokumen110 halamanThe Coregency of Ramses II With Seti I and The Date of The Great Hypostyle Hall at KarnakJuanmi Garcia MarinBelum ada peringkat

- Bibliography Daniel Snell - Religions of The Ancient Near EasDokumen6 halamanBibliography Daniel Snell - Religions of The Ancient Near EasRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- 2012 A Selected Bibliography of Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine (DRAFT)Dokumen41 halaman2012 A Selected Bibliography of Ancient Mesopotamian Medicine (DRAFT)Rupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Collins, Billie Jean - HittitologyDokumen20 halamanCollins, Billie Jean - HittitologyRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Unal, Ahmet - The Power of Narrative in Hittite Literature - 1989Dokumen15 halamanUnal, Ahmet - The Power of Narrative in Hittite Literature - 1989Rupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Byrd, Andrew Miles - Deriving Dreams From The Divine - HittiteDokumen11 halamanByrd, Andrew Miles - Deriving Dreams From The Divine - HittiteRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Jacobus - Table of ContentDokumen2 halamanJacobus - Table of ContentRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Zeitlyn - Finding Meaning in The Text - PRocess of Interpretation in Text Based Divination - 2001Dokumen17 halamanZeitlyn - Finding Meaning in The Text - PRocess of Interpretation in Text Based Divination - 2001Rupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Writing As Oracle As Law - by Ben-DovDokumen18 halamanWriting As Oracle As Law - by Ben-DovRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Jacobus - Table of ContentDokumen2 halamanJacobus - Table of ContentRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- HITTITE VIEWS OF SIN AND RELIGIOUS SENSIBILITYDokumen6 halamanHITTITE VIEWS OF SIN AND RELIGIOUS SENSIBILITYRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- "Personifications and Metaphors in Babylonian Celestial Omina" - RochbergDokumen12 halaman"Personifications and Metaphors in Babylonian Celestial Omina" - RochbergRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Shupak, Nili - The Hardening of Pharaoh's Heart in Exodus Seen Negative in Bible But Positive in EgyptDokumen7 halamanShupak, Nili - The Hardening of Pharaoh's Heart in Exodus Seen Negative in Bible But Positive in EgyptRupert84Belum ada peringkat

- Part CDokumen2 halamanPart CNorainun AzwaBelum ada peringkat

- Upload 1 Document To Download: The Mo Pai Training Manual PDFDokumen3 halamanUpload 1 Document To Download: The Mo Pai Training Manual PDFBlack MapleBelum ada peringkat

- N1 Grammar ListDokumen10 halamanN1 Grammar ListganaivyjoyBelum ada peringkat

- Hopkins, Belinda - Just Schools A Whole School Approach To Restorative JusticeDokumen210 halamanHopkins, Belinda - Just Schools A Whole School Approach To Restorative Justiceconvers3Belum ada peringkat

- Kami Export - Agij - Promotion - of - Nineteenonea - Media - PVT - LTD - Ors - V - Union - of - India - Ors - and - Connected - PILDokumen33 halamanKami Export - Agij - Promotion - of - Nineteenonea - Media - PVT - LTD - Ors - V - Union - of - India - Ors - and - Connected - PILMayank GandhiBelum ada peringkat

- Developments in Contract Law 2013 SingaporeDokumen6 halamanDevelopments in Contract Law 2013 SingaporeJoshua NgBelum ada peringkat

- Adverse Action NoticeDokumen2 halamanAdverse Action NoticeChad EdlerBelum ada peringkat

- Lintonjua, Jr. v. Eternit Corporation: G.R. No. 144805, 8 June 2006 FactsDokumen3 halamanLintonjua, Jr. v. Eternit Corporation: G.R. No. 144805, 8 June 2006 FactsMary Fatima BerongoyBelum ada peringkat

- Understanding the National Service Training ProgramDokumen7 halamanUnderstanding the National Service Training ProgramAether SkywardBelum ada peringkat

- NY Conference of Mayors LetterDokumen6 halamanNY Conference of Mayors LetterAmanda FriesBelum ada peringkat

- PFR Cases (1-37)Dokumen143 halamanPFR Cases (1-37)VanillaSkyIIIBelum ada peringkat

- TP BaccayBautista FinalDokumen5 halamanTP BaccayBautista FinalMaricel Ann Baccay100% (1)

- Responsive Document - CREW: Department of The Interior: Regarding Efforts by Wall Street Investors To Influence Agency Regulations: 8/28/2012 - FY 2011 FOIA LogDokumen141 halamanResponsive Document - CREW: Department of The Interior: Regarding Efforts by Wall Street Investors To Influence Agency Regulations: 8/28/2012 - FY 2011 FOIA LogCREWBelum ada peringkat

- ABSLI Multiplier FundDokumen1 halamanABSLI Multiplier FundTanveer AhmadBelum ada peringkat

- SIBA TESTING SERVICES MERIT LIST FOR PRIMARY TEACHER POSTDokumen11 halamanSIBA TESTING SERVICES MERIT LIST FOR PRIMARY TEACHER POSTzaka panhwarBelum ada peringkat

- 2021.04.06 BQ 56009 - ApartmentDokumen150 halaman2021.04.06 BQ 56009 - Apartmentali_dzakwan15Belum ada peringkat

- CHANGES IN PARTNERSHIP OWNERSHIPDokumen9 halamanCHANGES IN PARTNERSHIP OWNERSHIPKyla DizonBelum ada peringkat

- Installation of Mobile Towers in Residential Areas Case StudyDokumen3 halamanInstallation of Mobile Towers in Residential Areas Case StudyDinesh Patra100% (1)

- Appelant vs. REGINALD HILL, Minor and MARVIN HILL, As Father of Minor, Defendants-AppelleasDokumen4 halamanAppelant vs. REGINALD HILL, Minor and MARVIN HILL, As Father of Minor, Defendants-AppelleasQuiquiBelum ada peringkat

- CR 11 Darren Dwitama PDFDokumen5 halamanCR 11 Darren Dwitama PDFDarren LatifBelum ada peringkat

- Combining Home Office and Branch Financial StatementsDokumen34 halamanCombining Home Office and Branch Financial Statementskiki dwiBelum ada peringkat

- Judgement 05 Feb 2019Dokumen38 halamanJudgement 05 Feb 2019gunjeet singhBelum ada peringkat

- Child RefugeeDokumen18 halamanChild Refugeestpm_mathematicsBelum ada peringkat

- DPS North Fee - 2017-18Dokumen1 halamanDPS North Fee - 2017-18Thanuj Kumar Sc100% (1)

- Higher Education (C) Department: Government of KeralaDokumen34 halamanHigher Education (C) Department: Government of KeralaBiju ChackoBelum ada peringkat

- Case PPT of P.N.duda vs. P.shivShankar & Others.Dokumen12 halamanCase PPT of P.N.duda vs. P.shivShankar & Others.Simran SinghBelum ada peringkat

- RAM Foundation User ManualDokumen122 halamanRAM Foundation User ManualJohn DoeBelum ada peringkat

- Retailer Fact Sheet 20200506 EnglishDokumen8 halamanRetailer Fact Sheet 20200506 EnglishAnne Marie MaunderBelum ada peringkat

- Leo Strauss & NietzscheDokumen11 halamanLeo Strauss & Nietzschebengerson0% (1)

- ONGC 2010-11 Annual Report Highlights Record Production and ProfitsDokumen256 halamanONGC 2010-11 Annual Report Highlights Record Production and ProfitsAmit VirmaniBelum ada peringkat