Outsourcing - A Primer

Diunggah oleh

millyebDeskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Outsourcing - A Primer

Diunggah oleh

millyebHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Outsourcing: a primer

William M. Lankford

Richards College of Business, State University of West Georgia, Carrollton,

Georgia, USA

Faramarz Parsa

Richards College of Business, State University of West Georgia, Carrollton,

Georgia, USA

Definition of outsourcing

Outsourcing is defined as the procurement of

products or services from sources that are

external to the organization. For services,

this usually involves the transfer of opera-

tional control to the suppliers. In the current

environment of right-sizing, with a renewed

focus on core business activities, companies

can no longer assume that all organizational

services must be provided and managed

internally. Competitive advantage may be

gained when products or services are pro-

duced more effectively and efficiently by

outside suppliers. The advantages in out-

sourcing can be operational, strategic, or

both. Operational advantages usually pro-

vide for short-term trouble avoidance, while

strategic advantages offer long-term contri-

butions in maximizing opportunities.

It is estimated that every Fortune 500

company will consider outsourcing during

this decade and that 20 percent of them will

enter into a contract by the end of the decade.

A variety of firms already exhibit this trend.

General Electric Corporation has entered

into a five-year, $500 million contract with

Electronic Data Systems (EDS) to handle the

corporation's desktop computer procure-

ment, service, and maintenance activities

(Behara et al., 1995).

Overview of outsourcing

Why do senior managers sometimes prefer to

entrust outside firms with critical tasks? The

fact is, senior management often finds out-

side firms to be more cost-effective. While

middle managers often claim they can hire a

guy for 40 grand a year to do it cheaper, upper

management looks at things differently. They

know they will typically pay at least $100 per

hour to outsource, but they also know the job

will be done on time and in a predictable

fashion. And if it isn't, they can get somebody

else without going through the hassles of

hiring and firing employees. It is vision,

function, and economics that drive the need

for outsourcing (Harkins, 1996).

A recent study indicates that outsourcing

operations is the trend of the future and that

organizations already outsourcing activities

are pleased with the results. A year-long

international study by Arthur Andersen and

The Economist Intelligence Unit finds that 93

percent of corporations interviewed plan to

outsource in the next three years. Of those

that already outsource, 91 percent are satis-

fied with the results (Struebing, 1996).

The study, ``New Directions in Finance:

Strategic Outsourcing,'' is based on inter-

views with 50 global organizations plus a

survey of 303 senior executives throughout

North America and Europe. Said Dennis E.

Torkko, managing partner for Arthur An-

dersen's Contract Services Practice, ``The

study documents a clear trend to the use of

outsourcing as a competitive tool, rather

than just a simple means of cost control.

Especially relevant is the outsourcing of key

business processes and financial functions''

(Struebing, 1996).

The document includes outsourcing case

studies with Alcatel Italia, British Petroleum

Co., Houghton Mifflin, Mead, Microsoft, Octel

Communications, Plastics MFG, Sybase, Ta-

legen Holdings, Tektronix, and Zeneca

Group. Of the executives surveyed, 85 per-

cent outsource all or part of at least one

business function. The most widely out-

sourced activity is legal work (59 percent),

followed by shipping (41 percent), computer

information systems (36 percent), and pro-

duction and manufacturing (31 percent).

Twenty-six percent of the executives inter-

viewed currently outsource at least one

financial function; 42 percent expect to out-

source at least one financial function in the

next three years (Struebing, 1996).

Outsourcing and re-engineering

Re-engineering means ``new beginnings.'' It is

the search for a new way of organizing the

various elements of work. Re-engineering is

[ 310]

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

# MCB University Press

[ISSN 0025-1747]

Keywords

Manufacturing strategy,

Outsourcing, Purchasing

Abstract

Outsourcing is defined as the

procurement of products or ser-

vices from sources that are ex-

ternal to the organization. Firms

should consider outsourcing when

it is believed that certain support

functions can be completed faster,

cheaper, or better by an outside

organization. Tasks that are not

core competencies of the organi-

zation are candidates for being

contracted out. However, any skill

or knowledge that allows you to

serve your customer base better,

that deals directly with the pro-

duct or service you are trying to

put out of the door, is one that

must remain in-house. Today, the

outsourcing of selected organiza-

tional activities is an integral part

of corporate strategy. For cor-

porations, benefits of outsourcing

are substantial: reduced costs,

expanded services and expertise.

Outsourcing allows companies to

refocus their resources on their

core business. Corporations can

buy technology from a vendor that

would be too expensive for them

to replicate internally. For out-

sourcing to be successful the

decision needs to be an informed

one. Effective management of the

outsourcing relationships is an

organizational imperative.

``the fundamental rethinking and radical

redesign of business processes to achieve

dramatic improvements in critical, contem-

porary measures of performance, such as

cost, quality, service, and speed.'' Such

change is possible only through innovation

that ``encompasses the envisioning of new

work strategies, the actual process design

activity, and the implementation of the

change in all its complex technological, hu-

man, and organizational dimensions.''

The decision to outsource should address

the critical role of information and processes

in organizations, including the role that

systems play. If an entire function is to be

outsourced, sufficient provision should be

made in the outsourcing contract to deal with

current and future requirements of the

organization. Special attention should be

given to the potential need for innovative

solutions to be provided by the outsourcer,

and to the timing of these actions.

In this era of the virtual organization,

outsourcing traditional corporate tasks has

become popular. And doing so can be cost-

effective provided that the right tasks are

contracted out (Behara et al., 1995).

Consultants say that firms should consider

outsourcing when it is believed that certain

support functions can be completed faster,

cheaper, or better by an outside organization.

Tasks that are not core competencies of the

organization human resources, payroll and

benefits, information systems, even food

service in the cafeteria are ripe for being

contracted out.

On the other hand, any skill or knowledge

that allows you to serve your customer base

better, that deals directly with the product or

service you're trying to put out of the door, is

one that must remain in-house. Support

functions serve your employees better, so

you can give those tasks over to a group that

treats the employees like customers (Carey,

1995).

Today, the outsourcing of selected organi-

zational activities is an integral part of

corporate strategy. Historically, third party

participation in a company's business has

generally focused on the manufacture of

parts and components and the provision of

auxiliary services such as legal and travel

services. A more recent phenomenon, how-

ever, involves third party participation in the

management of the information systems (I/S)

function. Since information is a principal

resource in most businesses today, the con-

sequences of external control of a firm's

information system must be considered

carefully. The formulation and management

of the service contracts with information

services suppliers are critical issues (Behara

et al., 1995).

Advantages of outsourcing

Cutting costs is often seen as a major benefit

of outsourcing. However, this can lead to

disappointment. The Freight Transport

Association has produced research to show

that contracting out does not necessarily

save money. A much better reason is the

specialized knowledge that the contractor

can provide (Davies, 1995). Outsourcing

works best when it is an outgrowth of re-

engineering. Re-engineering means stepping

back to take a fresh look at a whole process

with an eye to discovering how it can be

reconceived and rebuilt, from the ground up,

as something that works better (Gamble,

1995).

In principle, re-engineering is bold, ra-

tional and efficiency-seeking. It respects no

sacred cows. It does not set out to protect jobs

or turf in any function, operation or depart-

ment, or another outsourcing agency. It sets

out to build better mouse traps, whatever the

consequences. Tradition resists re-engineer-

ing. So does entrenched self-interest. It is not

a naturally popular process (Gamble, 1995).

When re-engineering looks at who is best

suited to performing a particular task who

can do the task with the greatest efficiency

and the highest quality and then deter-

mines that it is not the in-house staff, out-

sourcing is likely to result. When competitive

pressures get strong, truly re-engineered

companies will rise to the top because they

have built the vital processes that work best

(Gamble, 1995).

Outsourcing is not a new fad but a solution

with a long, distinguished track record.

Using a wholesale lockbox is outsourcing,

pure and simple, but it happened before

outsourcing became faddish. It has prospered

because, for a great many companies, it

simply works better to direct the checks

straight to the bank, then let the most

efficient provider do the key-punching and

photocopying. Where management is bent on

staff reductions and prejudges outsourcing as

a way to keep essential functions operating

while deep staff cuts are carried out, then

mistakes are likely. The outcome might be a

lean, mean internal staff or a dispirited,

anorexic one (Gamble, 1995).

``Especially during the recession, there was

a tendency to feel that the reason to go for

outsourcing was to save money,'' explains

Mark Pope, commercial manager with out-

sourcing services company CMS. ``But if you

ask companies two or three years into a

contract what the benefits are, they tend to

suggest it is the opportunity to concentrate

on the business, the predictability of services

and the ability to manage the cost stream

[ 311]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

because there are no sudden surprises, such

as a demand for new equipment'' (Sweet,

1994).

Yet in many corporations today, down-

sizing has left administrative staffs unable to

deal with routine business transactions, let

alone the complicated assimilation and man-

agement required to successfully relocate a

large number of employees. Outsourcing

partnerships provide businesses with a vi-

able solution to the productivity problem.

Corporations can develop flexible outsour-

cing partnerships and programs designed to

meet their unique needs and culture (Run-

nion, 1993).

For corporations, benefits are substantial:

reduced costs, expanded services and exper-

tise, improved employee productivity and

morale, and a more positive corporate image.

Indeed, most outsourcing contracts target a

minimum 15 percent cost savings, sometimes

between 20 to 25 percent. To attain such

goals, it is essential to have multi-year

agreements so the economies of scale and

cost-cutting measures can take effect. Con-

tracts are usually multi-million dollar deals

signed for five years or more with perfor-

mance clauses built in (Manion et al., 1993).

``There are several primary reasons why a

firm considers outsourcing,'' according to

Kevin Moran, senior vice president with

Fidelity Institutional Retirement Services'

Benefits Center. He describes them as follows

(McCarthy, 1996):

.

Outsourcing allows companies to refocus

their resources on their core business.

.

Corporations can buy technology from a

vendor that would be too expensive for

them to replicate internally.

.

Outsourcing lets companies re-examine

their benefit plans, make them more

efficient, and save time and money while

improving efficiencies.

.

Companies outsource to improve the ben-

efit plan service level to their employees

by making the information more consis-

tent and more available.

.

A final possible reason is to reduce costs,

certainly over the longer term.

Fears that allowing someone else to run a

support function somehow means that the

company is no longer in control of its own

destiny have evaporated. Many organizations

tacitly admit they have little enough control

over their in-house support departments, and

see a legally enforceable contract with an

external supplier as a way of keeping the lid

on costs and improving the quality of the

service they get (Sweet, 1994).

Disadvantages of outsourcing

Unfortunately, determining core competen-

cies can sometimes be tricky, and a wrong

guess deadly. For instance, contracting out

training programs is common today, but

mismanagement there could wreak long-term

havoc. In another example, Darcy Hitchcock,

president of Axis Performance Advisors, in

Battle Ground, Washington, contends that

``IBM guessed wrong around 1980 when they

went into the PC market. They thought their

core competency was marketing, and not

creating an operating system or microchips.''

Microsoft was commissioned to write the

operating system, while Intel took on the task

of building the chips. Today, those two firms

are more vital to the computer industry than

IBM, whose outsourcing decisions helped

launch Microsoft and Intel (Carey, 1995).

When it comes to signing the contract,

some companies are in danger of signing a

blank check, they often feel it is too difficult

to sort out exactly what should be provided in

detail, and it is too easy for the suppliers to

simply say trust the other side (Sweet, 1994).

Despite the sound financial appeal, out-

sourcing is a topic that is still fraught with

emotional overtones. The fear of losing con-

trol is a major emotional stumbling block to

outsourcing. Such sentiments are somewhat

understandable. But outsourcing can be

more a partnership than a vendor/supplier

relationship. Some questions that should be

asked are (Manion et al., 1993):

.

What are the proposed savings measured

against? The dollar saving is probably

calculated against your current budget. Is

that the right basis for comparison? The

budget almost certainly has ``funny-

money'' corporate allocations in it, or

costs that won't go away with outsour-

cing. Shouldn't the comparison be made

against the actual cost of running the

department? No, that's still not good

enough. It should be made against what

your actual outlay would be if you were

operating at ``best-of-breed'' unit costs.

That's the price tag you'd like the out-

sourcer to beat; otherwise you'll be paying

a higher price for the service than it is

really worth.

.

Does the outsourcer have economies of scale

not available to you? Don't assume he

does. A 1991 study of information systems

providers failed to reveal any obvious

economies of scale across a large number

of data centers. If the in-house operation

understood exactly what you could

achieve yourself, it is very likely you

could save your company more than the

outsourcer can. You should have an edge,

[ 312]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

of course, because you don't pay yourself a

profit.

.

Is the guaranteed price a good deal? Is your

incremental cost of additional workload

equal to today's unit cost? In many cases

the marginal cost of adding workload to

the current base is considerably lower.

That could be critical to an accurate

evaluation. A wrong move here could

result in your outsourcing decision cost-

ing a lot more than you expected. Even the

best deals reported in the recent press

seem to pass on only about half the

potential benefit of decreasing unit costs.

.

Can the outsourcer buy equipment and

hardware cheaper? It is commonly held

that, because of the outsourcer's size and

diversity, he enjoys an appreciable edge in

buying power and flexibility. It is argued

that this coupled with greater ``granular-

ity'', allows him to keep the cost of hard-

ware additions below what smaller

operations can achieve. When you buy

capacity before it is really needed, you've

spent too much for it. Not only is the time

value of money important, but buying

hardware tomorrow is always cheaper

than buying it today. Adopting a ``just-in-

time capacity'' strategy may pay bigger

dividends than is generally recognized.

.

Tend your own knitting and leave support

operations to the specialists. These are

often heard cries, but be careful here too.

It doesn't follow that you should out-

source your support operations at any

cost. It still holds, though, that your

support operations should only be out-

sourced if it is cost effective to do so.

Outsourcing is often touted as a way to

handle thorny problems like a large book

value that is hard to swallow, an inflexible

leasing arrangement, staff relation diffi-

culties, and so on. Ask yourself whether

outsourcing is really the right way to deal

with such issues, or whether it just shifts

and disguises them. In any case, you

should understand what price you're

paying to avoid dealing with them directly

(Manion et al., 1993).

Process to determine if

outsourcing is the correct strategy

While outsourcing can often help control

costs, simplify operations, and keep a com-

pany focused on its core competencies, it

won't work unless it is properly implemen-

ted. Here are some guidelines (Kelley, 1995):

.

Determine what business you're in.

Quickly jot down the company's core

competencies and primary sources of

revenue. Obviously, these functions and

processes are areas that you don't want to

outsource. Whatever isn't on this list,

however, may be outsourced.

.

Look for outsourcing opportunities. Simi-

larly, find the functions or processes

within the company that don't make the

company unique or offer a clear competi-

tive advantage over other businesses.

Such non-strategic areas can often be

outsourced.

.

Evaluate costs. Try to determine just how

much is being spent on a function and

whether or not it can be done more

cheaply by an outside company. Set ob-

jectives. Realistically decide what an out-

source partner can do for the company.

Whether it is to cut costs, improve focus,

or free up resources, make certain the

goals are attainable.

.

Be cautious. Don't select an outsource

partner without careful examination.

After all, that business will be your

company's representative to both employ-

ees and customers.

.

Monitor. If you decide to outsource, set up

regular performance reviews or similar

criteria to measure the provider's perfor-

mance. Outsourcing isn't an excuse to

overlook an aspect of your business.

.

Be flexible. Even after deciding to out-

source, look at ways it can be improved.

Don't be afraid to make changes in the

ways a process is being handled.

.

Don't jump on the bandwagon. Just be-

cause outsourcing is a growing trend

doesn't mean it should be automatically

embraced. If a change isn't needed, don't

make one just for the sake of it.

It also can be dangerous to focus too

narrowly on a single, isolated process when

making an outsourcing decision. Such

choices should be made only after four

questions have been answered (Gamble,

1995):

1 What will be the net gain or loss in

efficiency and cost-effectiveness of using

outsourcing?

2 What will be the net gain or loss in

performance quality of using outsour-

cing?

3 What will be the net effect on the strength,

versatility and resourcefulness of the

treasury department if the duties in

question are outsourced?

4 What dependence on a third party will be

created by outsourcing, and how vulner-

able would the organization be if that

third party somehow became unable to

perform as expected?

[ 313]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

The outsourcing decision

A number of issues are involved in the

decision to outsource an organization's re-

sources. To summarize, key items to analyze

are scale economy, outsourcer expertise,

short- and long-term financial advantage

from the sale of resources, inability to

manage the function, strategic realignment,

and a need to focus on the core business.

Additional issues that typically are involved

and need to be considered in the context of a

specific firm's situation include (Behara et

al., 1995):

.

impact on company competitiveness;

.

identifying services to be outsourced;

.

the number of suppliers to be used;

.

ability to return to in-house operations if

required;

.

supplier reliability;

.

supplier service quality;

.

coordinating with the supplier and evalu-

ating performance;

.

flexibility in the products offered by the

supplier;

.

providing the latest/advanced technology

and expertise.

Steps that need to be completed to

implement the transition from an

in-house service to an outsourced

service

The purchasing function must be involved in

the negotiations and contract development

when outsourced services are purchased.

This procedure will have a positive impact on

the quality and value the organization

receives because of purchasing's expertise

in procurement issues related to service

contracts. Corporate risk management,

legal, and strategic planning groups

should also be involved. This will ensure that

the strategic impact of the outsourcing con-

tract is adequately evaluated (Behara et al.,

1995).

As in the case of all other procurement,

purchasers of outsourced services should not

be willing to accept the standard contract

offered by most suppliers. The following

factors should be an integral part of the

planning and conduct of the acquisition

process:

.

Purchasing representation on the supplier

selection team.

.

Competence factors to use in evaluating

suppliers (e.g. flexibility, understanding

the company's business, technology lea-

dership).

.

Bid evaluation procedures, including the

specific evaluation of low bids.

.

A precisely defined scope of work, detail-

ing the nature and extent of collaboration

between buyer and supplier.

.

Safeguards for performance and cost con-

trol.

.

Methods and procedures for measuring

supplier performance.

The specific needs of the organization should

be matched with the supplier's capabilities

during negotiations so as to develop a

contract around a shared vision. A cross-

functional team with members from a variety

of decision-making levels is required to

assess the company's needs. Such a team is

also required to manage the contract after its

execution. Outsourcers should have the fi-

nancial and technological incentive to help

the company migrate to technology that is

suitable to the organization. Suppliers that

have a good understanding and an interest in

the outsourcing firm's business will be better

positioned to help define mutually beneficial

goals.

Supplier performance should be evaluated

on the twin dimensions of technical and

functional quality. Technical quality in-

cludes maintaining the required response

time, minimizing system down time, provid-

ing error-free service, and utilizing leading

edge technology. Functional quality, in es-

sence, is the quality of customer service.

Outsourcing contracts can be all-inclusive,

modular (focusing on specific operations), or

turnkey (specific jobs). While turnkey con-

tracts historically have represented the typi-

cal arrangement between buying firms and

outsourcing suppliers, the modular and all-

inclusive approaches characterize today's

outsourcing relationships. In identifying po-

tential outsourcing suppliers, the firm's own

division might well be considered as a

possible alternative. Internal audits indicate

that a division that rationalizes its opera-

tions can generally outbid the outsourcing

supplier (Behara et al., 1995).

If the decision to investigate the benefits of

outsourcing is made, be prepared for a

lengthy evaluation and implementation pro-

cess. Don't focus solely on short-term needs;

this is a major event that one wants to

avoid repeating. Firms need to take a long-

term view of the move to outsourcing. Ask,

``Are they dedicated to the business? Will

they stay with the outsourcing business?''

The second thing to ask is, ``If I outsource

with a vendor, am I locked into that vendor?

Can I make a change in corporate direction

and decide to in-source at some point in the

future, or change to a second vendor?''

(McCarthy, 1996)

[ 314]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

Example of outsourcing

The outsourcing of the Southwire Company

trucking fleet

Southwire Company grew to be the largest

producer of electrical wire and cable in the

USA. One of the competitive advantages

developed by Southwire was its customer

service with the ability to deliver products

directly to the customer with its own fleet of

trucks. Southwire acquired its own fleet of

trucks since they were located in a rural area

of Georgia when the company was founded

and lacked access to commercial transporta-

tion. Southwire turned this disadvantage, the

lack of commercial transportation, to a

competitive advantage by using its own fleet

of trucks to deliver product directly to the

customer, reducing the order lead time for

the customer, and then using the return trip,

the back haul, to pick up materials and

supplies from vendors, thus reducing the

shipping cost of these items. For these and

other reasons the Southwire truck fleet was a

high profile part of the company culture, and

a source of company pride.

By the mid-1990s Southwire began to con-

sider the outsourcing of its fleet operation.

There were several reasons for considering

outsourcing of the fleet. The fleet operation

was not a part of its core business, yet it

represented a fair amount of the asset base of

the company and the number of employees of

the company. Increased cost and time was

required for overseeing and compliance with

increasing government regulations, i.e. DOT,

ICC, drug testing, and various federal and

state agencies. The fleet of approximately 100

tractor trailers was becoming old, obsolete,

and lacked the safety features found on the

newer model trucks. To replace and upgrade

the fleet would require a considerable in-

vestment. The potential liability cost of

operating one's own fleet became a major

issue. Southwire is self-insured, and had

experienced some unfortunate road accidents

involving its trucks. This liability exposure

plus the negative press in having an accident

with the company's name on the side of the

truck involved was deemed a cost that could

be avoided with an outsourced fleet. The cost

of payroll, medical and other benefits for the

mechanics, drivers, and other fleet personnel

was a growing part of the payroll expense of

the company.

The down side of outsourcing was identi-

fied as the cost of perception by the custo-

mers. Having the product delivered by a

third party would the customer notice, or

really care, so long as the product was

delivered on time and to the customers'

expectation and satisfaction? Not having the

Southwire name on the truck and the result-

ing advertising from having rolling bill-

boards. And perhaps the most important, the

losing of control to a third party of the fleet

and delivery of the product to the customer.

For these and other reasons Southwire

phased out its own fleet operation in the Fall

of 1996 and outsourced the fleet operation to

Schneider National Dedicated Operation of

Green Bay, Wisconsin. Schneider was chosen

because they combine leading-edge technol-

ogy with a full list of transportation services

to engineer solutions for customers. South-

wire has stated ``With Schneider, Southwire

is able to benefit from the advanced technol-

ogy and take advantage of the efficiency of

using a large business like Schneider devoted

solely to transportation. This means South-

wire can concentrate on what we do best

manufacture wire and cable products'' (Den-

nis, 1997).

Conclusion

The decision to outsource can lead to com-

petitive advantages for businesses. For out-

sourcing to be successful the decision needs

to be an informed one. Good, hard, detailed

information in the hands of strong manage-

ment can help avoid a costly step, one that is

not easily reversed. Ultimately, for outsour-

cing in any form to be successful, quick

response times to strategic opportunities and

threats are essential. Effective management

of the outsourcing relationships is an orga-

nizational imperative.

References

Allerton, H. (1996), ``Outsourcing outlook,''

Training, Vol. 50 No. 9, p. 9.

Anon (1995), ``Avoiding disasters in outsourcing,''

Management Accounting, London, Vol. 73 No.

11, p. 11.

Anthes, G.H. (1991), ``Outsourcing may be the only

answer for many,'' Computerworld, Vol. 25

No. 12, pp. 51, 54.

Behara, R.S., Gundersen, D.E. and Capozzoli, E.A.

(1995), ``Trends in information systems out-

sourcing,'' International Journal of Purchas-

ing, Vol. 31 No. 2, pp. 46-51.

Bing, S. (1996), ``Outsource this, you turkeys!!,''

Tax Executive, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 16-17.

Carey, R. (1995), ``Consider the outsource,'' In-

centive: Performance Supplement, p. 4.

Davies, M. (1995), ``Outsourcing: the transport,''

Director, Vol. 49 No. 1, p. 41.

Dennis, C. (1997), ``Southwire and Schneider:

partnership for the future,'' Inside Southwire,

Vol. 14 No. 5, p. 4.

Gamble, R.H. (1995), ``Inside outsourcing,'' Corpo-

rate Cashflow, Vol. 16 No. 8, p. 2.

[ 315]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

Harkins, J. (1996), ``Why buy outside design?,''

Machine Design, Vol. 68 No. 10, p. 126.

Higgins, K.T. (1995), ``Managers for rent,'' Credit

Card Management, Vol. 8 No. 9, pp. 34-46.

Hise, P. (1996), ``Real-time computer help,'' Inc.,

Vol. 18 No. 2, p. 107.

Kelley, B. (1995), ``Before you outsource,'' Journal

of Business Strategy, Vol. 16 No. 4, p. 41.

McCarthy, E. (1996), ``To outsource or not to

outsource what's right for you?,'' Pension

Management, Vol. 32 No. 4, pp. 12-17.

Manion, R., Burkett, D. and Wiffen, B. (1993),

``Why it makes sense to break the I. S.

shackles and five reasons why it may not,''

I.T. Magazine, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 14-19.

Margolis, N. (1992), ``Outsourcing proves itself a

useful business tool no fad,'' Computerworld,

Vol. 26 No. 39, p. 88.

Runnion, T. (1993), ``Outsourcing can be a pro-

ductivity solution for the '90s,'' HR Focus, Vol.

70 No. 11, p. 23.

Struebing, L. (1996), ``Outsourcing is the answer

or is it?,'' Quality Progress, Vol. 29 No. 3, p. 20.

Sweet, P. (1994), ``It's better out than in,'' Accoun-

tancy, Vol. 114 No. 1211, pp. 61-5.

Application questions

1 Is there a trade-off between the cost

savings and flexibility achieved by out-

sourcing and the level of service which

can be expected?

2 Can a firm have its functions completely

outsourced? What would happen if it did?

[ 316]

William M. Lankford and

Faramarz Parsa

Outsourcing: a primer

Management Decision

37/4 [1999] 310316

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Outsourcing: A Primer: KeywordsDokumen7 halamanOutsourcing: A Primer: KeywordsWilly NyimbochiBelum ada peringkat

- MIS Assignment 1Dokumen18 halamanMIS Assignment 1Nazmul HaqueBelum ada peringkat

- Ghode S War Janardan 2008 Emerald OutsourcingDokumen17 halamanGhode S War Janardan 2008 Emerald OutsourcingRejish ShresthaBelum ada peringkat

- A Study of Human Resource Outsourcing in PDFDokumen10 halamanA Study of Human Resource Outsourcing in PDFAlin DanciBelum ada peringkat

- Strategic Outsourcing ProjectDokumen42 halamanStrategic Outsourcing ProjectshikhaBelum ada peringkat

- Preparing An Outsourcing Cost/Benefit AnalysisDokumen7 halamanPreparing An Outsourcing Cost/Benefit AnalysissirishaakellaBelum ada peringkat

- Outsourcing - Compiled by Halley ThokchomDokumen31 halamanOutsourcing - Compiled by Halley ThokchomhalleyworldBelum ada peringkat

- Final Project On Outsourcing in IndiaDokumen23 halamanFinal Project On Outsourcing in IndiaLaxman Zagge100% (3)

- Outsourcing.... Benefiting OrganizationsDokumen8 halamanOutsourcing.... Benefiting OrganizationsPrashanthfeedbackBelum ada peringkat

- Motives and Benefits of OutsourcingDokumen20 halamanMotives and Benefits of OutsourcingVarun RamzaiBelum ada peringkat

- HR Trends and IssuesDokumen6 halamanHR Trends and Issueszendikar21Belum ada peringkat

- Hackett HR Outsourcing Best Practices PDFDokumen8 halamanHackett HR Outsourcing Best Practices PDFDipak ThakurBelum ada peringkat

- HR OutsourcingDokumen22 halamanHR OutsourcingRonnald WanzusiBelum ada peringkat

- Initial Stages of EvolutionDokumen5 halamanInitial Stages of EvolutionVivek MulchandaniBelum ada peringkat

- Business Process Outsourcing DefinedDokumen19 halamanBusiness Process Outsourcing DefinedMohammad Adil ChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- Indication and Outsourcing StrategyDokumen11 halamanIndication and Outsourcing StrategyXYZBelum ada peringkat

- Research Proposal - Marvingrace M.Dokumen16 halamanResearch Proposal - Marvingrace M.tyrion mesandeiBelum ada peringkat

- My Long Term Reseach WorkDokumen16 halamanMy Long Term Reseach Workaminat abiolaBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Outsourcing?Dokumen4 halamanWhat Is Outsourcing?Tabitha WatsaiBelum ada peringkat

- Business Process Outsourcing OooooooooooooooooDokumen19 halamanBusiness Process Outsourcing OooooooooooooooooMohammad Adil ChoudharyBelum ada peringkat

- Sad Ganesh AssignmenttDokumen10 halamanSad Ganesh AssignmenttAadhavan GaneshBelum ada peringkat

- The Outsourcing Revolution (Review and Analysis of Corbett's Book)Dari EverandThe Outsourcing Revolution (Review and Analysis of Corbett's Book)Belum ada peringkat

- Aarti BhajanDokumen86 halamanAarti Bhajanचेतांश सिंह कुशवाहBelum ada peringkat

- International Business and Trade - Finals Case StudyDokumen7 halamanInternational Business and Trade - Finals Case StudyIceeh RolleBelum ada peringkat

- Global Delivery Model Pensions AdministrationDokumen10 halamanGlobal Delivery Model Pensions AdministrationRamanah VBelum ada peringkat

- WK1-BUS5040 - SURVEY OF PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT-topic 1 Introduction-2Dokumen28 halamanWK1-BUS5040 - SURVEY OF PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS MANAGEMENT-topic 1 Introduction-2Moses SosiBelum ada peringkat

- Planning Successful Partnership in The Process of OutsourcingDokumen9 halamanPlanning Successful Partnership in The Process of OutsourcingMousumi ModakBelum ada peringkat

- Types of Outsourcing: Information Technology Outsourcing (ITO)Dokumen4 halamanTypes of Outsourcing: Information Technology Outsourcing (ITO)Uyai LizamayBelum ada peringkat

- Putting The Organizational Knowledge System Back Together Again: A Strategic Knowledge Management Typology For Outsourcing FirmsDokumen27 halamanPutting The Organizational Knowledge System Back Together Again: A Strategic Knowledge Management Typology For Outsourcing FirmsMike SajaBelum ada peringkat

- Business Process Outsourcing and India: October 2007Dokumen23 halamanBusiness Process Outsourcing and India: October 2007Sasha GomezBelum ada peringkat

- Research Study (42662) Madan Lal GaireDokumen2 halamanResearch Study (42662) Madan Lal Gairemadan GaireBelum ada peringkat

- HR OutsourcingDokumen22 halamanHR OutsourcingRagini Johari50% (4)

- Dissertation OutsourcingDokumen6 halamanDissertation OutsourcingWebsitesThatWritePapersForYouCanada100% (1)

- Outsourcing As A Business Strategy (39Dokumen2 halamanOutsourcing As A Business Strategy (39Susan BvochoraBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Procu.t Ch-2Dokumen21 halamanBasic Procu.t Ch-2feyisaabera19Belum ada peringkat

- OutsourcingDokumen7 halamanOutsourcingMeryl Jan SebomitBelum ada peringkat

- NAME: M.Razee QureshiDokumen8 halamanNAME: M.Razee QureshiS YBelum ada peringkat

- Service Operations 2017 2018Dokumen23 halamanService Operations 2017 2018Vijay Singh ThakurBelum ada peringkat

- Outsourcing 2Dokumen14 halamanOutsourcing 2Garang GeorgeBelum ada peringkat

- OutsourcingDokumen9 halamanOutsourcingapi-19960865Belum ada peringkat

- Outsourcing Jobs Research PaperDokumen7 halamanOutsourcing Jobs Research Paperafmbemfec100% (1)

- CORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessDokumen9 halamanCORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessBabu GeorgeBelum ada peringkat

- TQM-First Assignment-Semester 4Dokumen5 halamanTQM-First Assignment-Semester 4MS PMBelum ada peringkat

- The Outsourcing Revolution: Focus Take-AwaysDokumen5 halamanThe Outsourcing Revolution: Focus Take-AwaysTkay C CappaBelum ada peringkat

- Outsourced Marketing It Is A Communication That MattersDokumen24 halamanOutsourced Marketing It Is A Communication That Matterslocnguyenthanh.workBelum ada peringkat

- Cost Savings TechniquesDokumen3 halamanCost Savings TechniquesPanda PandaBelum ada peringkat

- Report On OutsourcingDokumen28 halamanReport On Outsourcingvikram3110100% (1)

- Outsourcing The Innovation Process of Alashka: Student Name: Instructor NameDokumen7 halamanOutsourcing The Innovation Process of Alashka: Student Name: Instructor NameMuhammad NaveedBelum ada peringkat

- (A) Describe The Notion of Core CompetencyDokumen9 halaman(A) Describe The Notion of Core Competencylulu luvelyBelum ada peringkat

- HR Outsourcing: First ImpressionsDokumen30 halamanHR Outsourcing: First ImpressionsUday GowdaBelum ada peringkat

- SHRM Project ON Future Trends in HRM: Submitted To: By: DR Sujata Taru Taneja D-8 Disha Bhagat D-28Dokumen31 halamanSHRM Project ON Future Trends in HRM: Submitted To: By: DR Sujata Taru Taneja D-8 Disha Bhagat D-28Neha ThukralBelum ada peringkat

- Cost Benefits and Critical Success FactorsDokumen3 halamanCost Benefits and Critical Success FactorsHamza HasnyneBelum ada peringkat

- Outsourcing by Prashant PriyadarshiDokumen14 halamanOutsourcing by Prashant PriyadarshiPrashantBelum ada peringkat

- The Advantages of OutsourcingDokumen12 halamanThe Advantages of OutsourcingManpreet Kaur Sekhon100% (1)

- Outsourcing - The Modern Trend of Accounts Management: Wutan Huatan Jisuan Jishu ISSN:1001-1749Dokumen16 halamanOutsourcing - The Modern Trend of Accounts Management: Wutan Huatan Jisuan Jishu ISSN:1001-1749Jackson KasakuBelum ada peringkat

- HR OutsourcingDokumen22 halamanHR Outsourcingleon dsouzaBelum ada peringkat

- WP Succ Factors For ConsulDokumen4 halamanWP Succ Factors For ConsulrribarraBelum ada peringkat

- Online AssignmentDokumen7 halamanOnline AssignmentAppu M ThandalathuBelum ada peringkat

- RUCC Ministries - Contract For StaircaseDokumen36 halamanRUCC Ministries - Contract For StaircaserendaninBelum ada peringkat

- Maharasthra IAS OfficersDokumen4 halamanMaharasthra IAS Officersdevasish100% (1)

- 11) San Lorenzo Development Corp. Vs CADokumen2 halaman11) San Lorenzo Development Corp. Vs CAamareia yapBelum ada peringkat

- State Tax Return NC-F14Dokumen2 halamanState Tax Return NC-F14aklank_218105Belum ada peringkat

- Human Develop Report Himachal Pradesh 2002 Full ReportDokumen399 halamanHuman Develop Report Himachal Pradesh 2002 Full ReportdeepelBelum ada peringkat

- Position PaperDokumen2 halamanPosition PaperJelly Ann RimalosBelum ada peringkat

- A Success Stor Fortuny of Fortune Company Gar Forgings 14Dokumen15 halamanA Success Stor Fortuny of Fortune Company Gar Forgings 14Bhabya KumariBelum ada peringkat

- EY Report - Fuelling The Next Generation - A Study of The UK Upstream Oil & Gas WorkforceDokumen48 halamanEY Report - Fuelling The Next Generation - A Study of The UK Upstream Oil & Gas WorkforcedreamcatcherBelum ada peringkat

- What Is PESTEL Analysis and How It Can Be Used For Salomon and The Treasury Securities Auction Case StudyDokumen4 halamanWhat Is PESTEL Analysis and How It Can Be Used For Salomon and The Treasury Securities Auction Case StudyDivyendu SahooBelum ada peringkat

- WalmartDokumen26 halamanWalmartPuneetGuptaBelum ada peringkat

- A Comparative Study Between Dhaka Stock Exchange and London Stock ExchangeDokumen38 halamanA Comparative Study Between Dhaka Stock Exchange and London Stock ExchangeNur RazeBelum ada peringkat

- Geography Chapter 21-Central and Southwest AsiaDokumen2 halamanGeography Chapter 21-Central and Southwest AsiaTheGeekSquadBelum ada peringkat

- Ijaret: ©iaemeDokumen12 halamanIjaret: ©iaemeIAEME PublicationBelum ada peringkat

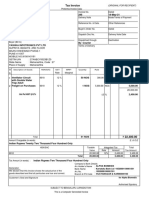

- Tax Invoice: Mudass Ir Syed ZaidiDokumen2 halamanTax Invoice: Mudass Ir Syed ZaidiRohit ChhabraBelum ada peringkat

- Tax BulletinDokumen72 halamanTax BulletinSamuel Mervin NathBelum ada peringkat

- Innovations in Textile and Apparel IndustryDokumen114 halamanInnovations in Textile and Apparel IndustryKumud BaliyanBelum ada peringkat

- Residential Status MCQDokumen6 halamanResidential Status MCQSarvar PathanBelum ada peringkat

- SAC (Services Accounting Codes) List & GST Rates On ServicesDokumen61 halamanSAC (Services Accounting Codes) List & GST Rates On ServicesPower RoboticsBelum ada peringkat

- Adaptive ReuseDokumen5 halamanAdaptive Reuseharshita sethiBelum ada peringkat

- Kel 3 Bahasa Inggris Niaga - Modul 2 KB 2Dokumen19 halamanKel 3 Bahasa Inggris Niaga - Modul 2 KB 2Putra RakhmadaniBelum ada peringkat

- Fsapm AssignmentDokumen19 halamanFsapm AssignmentAnkita DasBelum ada peringkat

- Government AccountingDokumen60 halamanGovernment AccountingKath Chu100% (2)

- Chapter 2 - Markets and Government in A Modern EconomyDokumen12 halamanChapter 2 - Markets and Government in A Modern EconomyStevenRJClarke100% (5)

- Philippine Inflation Rate Surges to 4.7% in February 2021Dokumen24 halamanPhilippine Inflation Rate Surges to 4.7% in February 2021JBBelum ada peringkat

- Provisional Selection List - M ComDokumen3 halamanProvisional Selection List - M ComAachal SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Tax Invoice: Alpha Biomedix 295 14-May-21Dokumen3 halamanTax Invoice: Alpha Biomedix 295 14-May-21Neha UkaleBelum ada peringkat

- Basic Economic Problem & ScarcityDokumen3 halamanBasic Economic Problem & ScarcityTaufeek Irawan100% (1)

- JEB Sharpe Style AnalysisDokumen8 halamanJEB Sharpe Style AnalysisJhones SmithBelum ada peringkat

- U.S. Tax Court Petition Kit PDFDokumen5 halamanU.S. Tax Court Petition Kit PDFHansley Templeton CookBelum ada peringkat