Climbing The Ladder From Novice To Expert Plastic Surgeon

Diunggah oleh

Luiggi Fayad0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

59 tayangan7 halamanThis article reviews the nature of novice and expert thinking. It suggests ways of viewing surgical trainees as they progress through the process. Expertise is not passively acquired by increasing experience.

Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Climbing the Ladder From Novice to Expert Plastic Surgeon

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniThis article reviews the nature of novice and expert thinking. It suggests ways of viewing surgical trainees as they progress through the process. Expertise is not passively acquired by increasing experience.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

59 tayangan7 halamanClimbing The Ladder From Novice To Expert Plastic Surgeon

Diunggah oleh

Luiggi FayadThis article reviews the nature of novice and expert thinking. It suggests ways of viewing surgical trainees as they progress through the process. Expertise is not passively acquired by increasing experience.

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 7

EDUCATORS SERIES

Climbing the Ladder from Novice to Expert

Plastic Surgeon

Robert A. Weber, M.D.

H. Thomas Aretz, M.D.

Temple, Texas; and Boston, Mass.

Summary: This article reviews the nature of novice and expert thinking and

shows how pattern recognition is a key distinction between the two. The article

also discusses the ladder that learners climb as they move from medical student

to senior staff surgeon and suggests ways of viewing surgical trainees as they

progress through the process so that learning activities can be adopted that best

fit them. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 130: 241, 2012.)

O

n any day in the surgeons lounge, you can

see medical students learning to tie knots

onarmchairs, residents reviewing the steps

of an operation, and senior staff working through

the best way to manage an unexpected outcome.

How did we move from novice to expert? In a

related vein, as teachers we have learned that it is

a good technique to ask students questions to en-

gage them in active learning. Why, then, does the

Socratic method work so well with one group of

residents and so poorly with another?

Expertise is not passively acquired by increas-

ing experience. Practice makes permanent, not

perfect. Expertise is about improving perfor-

mance and not the routine completion of rote

tasks. Deliberate practice is one concept that at-

tempts to capture this distinction.

1

We know that

meaningful learning and progression of skills

takes place when learners are challenged, given

feedback through experts or coaches, and pro-

vided the opportunity to practice and learn. Ex-

pert plastic surgeons approach challenges in a

different fashion than surgical interns. Knowing

these differences can allow teachers and students

to design learning activities to promote the pro-

cession from novice thinking to expert thinking.

At the same time, cognizance of the various stages

along the continuumand a learners state of mind

as a result of their location on that path can help

a teacher use techniques appropriate for a partic-

ular learner. This gives the student surgeons in-

sight into to why they may respond the way they do

in certain situations.

FROM FIRST YEAR RESIDENT TO

SENIOR STAFF SURGEON

Novice versus Expert Thought Processes

The expert plastic surgeon differs from the

intern in more than just fund of knowledge. Al-

though it is true that a senior surgeon knows more

about plastic surgery than a postgraduate year-1

plastic surgery resident, what really separates them

is their varying thought processes. A typical prob-

lem-solving loop and its standard stages are

shown in Figure 1, left.

What Is the Problem?

This requires the surgeon to recognize that

there is a problem, determine its various parts and

their meaning, and prioritize the various aspects

of the problem according to importance. Experi-

enced surgeons are able to recognize when things

are out of the ordinary and see the problem. They

can easily break the situation down to its compo-

nents, recognize patterns, and then prioritize ac-

cording to importance.

2

Novices often have diffi-

culties distinguishing normal from abnormal,

cannot identify the parts of the problem or rec-

ognize patterns, or determine what is important.

These are skills that can be learned and practiced

(e.g., Bowdens suggestion of asking a learner to

summarize the important aspects of a case into

one sentence).

3

What Are My Options?

Rarely do problems have only one solution.

Whereas experts have learned to streamline the

From the Department of Surgery, Division of Plastic Surgery,

Scott & White Healthcare/Texas A&M Health Science Cen-

ter College of Medicine, and Harvard Medical School and

Harvard Macy Institute.

Received for publication October 4, 2011; accepted January

3, 2012.

Copyright 2012 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons

DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b374

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest

to declare in relation to the content of this article.

www.PRSJournal.com 241

process of formulating treatment plans and

backup options through use of analogies and spe-

cialized routines, novices are prone to trial and

error, exhaustive but often irrelevant inquiries,

and exclusion of pertinent data based on initial

biases.

4

Unlike experts, novices do not have sig-

nificant expertise and experience in applying gen-

eral problem-solving techniques to a large set of

specific cases.

5

What Is My Decision? What Do We Do?

Experts often make use of shortcuts when

making decisions, which may be superior to de-

tailed decision algorithms, provided that the de-

cision maker is able to recognize the exceptions.

6

Novices are not capable of doing this but need to

rely on cumbersome, detailed, and often iterative

means of coming to a decision.

Actions

Clearly, what experts do and howthey perform

differs quite dramatically from the way novices do

things and their level of performance. The next

section addresses some of the issues concerning

skills.

Are We Done and What Have We Learned?

This last step is one that defines deliberate

practice and one of the major differences between

novices and experts. Experts always reflect to ex-

amine what they could have done better, and

what the essence of the experience was that can

be taught to others. Novices should be encour-

aged to reflect, but self-assessment requires a

certain base level of knowledge, and teachers

need to encourage reflection by beginners by

modeling self-reflection.

7

Figure 1, right, illustrates the distinctions dis-

cussed above. Overall, the chief attributes of an

expert as opposed to a novice are pattern recog-

nition and ability to process discordant or incom-

plete data (Table 1).

811

Although a fund of knowl-

edge is critical and must be developed, the seasoned

plastic surgeon does not have all the answers but

does know how to make decisions without complete

information.

12

Knowing the characteristics of expert thinking

allows plastic surgery educators to develop curri-

cula that begin with the dissemination of infor-

mationandalsoinclude discussions of context and

patterns. Pangaro developed the RIME schema of

developing these capabilities.

13

Dividing the various

stages into the categories of reporter (reliable data

gathering and reporting), interpreter (prioritizing,

analyzing, synthesizing), manager (presents options

and makes decisions), and educator (posing new

questions, teaching), the authors created a develop-

mental schema for clinical reasoning and decision

making.

The Developmental Ladder

Building on their study of chess players and

pilots, Hubert and Stuart Dreyfus published a

model of skills acquisition in 1980.

14,15

They found

that learners pass through levels of proficiency

change, from a reliance on abstract principles to

Fig. 1. (Left) Thevarious stages of problem-solving. Novices typically movearoundthecircle, whereas experts appear tobeable

tomovealongtheredarrow, shorteningtheprocess dramatically. (Right) Superimpositionof skills andcharacteristics of experts

that enable them to accomplish this (see text for details).

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery July 2012

242

the use of past experience, and adjust from anal-

ysis of all data that are equally important to the

recognition of key relevant data as described

above. William Howell, working in the field of

communications, writes of similar findings and

describes a competence ladder with four stages:

Stage 1: Unconscious incompetence. Learners

are unaware that they do not have a particular

competence.

Stage 2: Conscious incompetence. Learners know

that they want to do something but are unable

to do it.

Stage 3: Conscious competence. Learners can

achieve a particular task but must think about

every step.

Stage 4: Unconscious competence. Learners no

longer have to think about knowing or per-

forming a task.

16

Using Howells system, the conscious compe-

tence ladder gives insight to learners and guid-

ance to teachers. During the conscious incompe-

tence phase, residents have the reassurance that

although learning is frustrating, the situation will

improve. At the stage of unconscious competence,

the model reminds residents to value the skills

acquired and show compassion to those behind.

Teachers can be aware of the emotional aspects

associated with learning and adjust methods ac-

cording to the level of their resident.

In preparing to review the ladder, there are

important principles to keep in mind. First, there

are other theories about moving from novice to

expert (e.g., Dreyfus outlines a five-step process

that has been the basis for much useful research

and application).

5,15

These steps are generaliza-

tions intended to begin to give insight. Second,

people move up at different rates, and there is no

set time for each stage. Some residents achieve a

level but fail to make the jump to the next step.

The learning process is spiral in nature, and some

learners move forward more easily in some areas

than in others. At times, it can seemthat a resident

moves backward.

17

This is why many postgraduate

year4 plastic surgery residents are discouraged

during their first few months of plastics residency:

they moved from being consciously competent

surgeons to consciously incompetent plastic sur-

geons. Astudent canbe a novice insome areas and

expert in another. Furthermore, a single class can

have students in various stages.

THE FOUR RUNGS

1: Unconscious Incompetent (You Do Not

Know That You Do Not Know)

Inthis stage, the learner is not cognizant of the

existence or relevance of many of the skill areas,

not aware of a particular deficiency in the area of

concern, and must become conscious of his or her

incompetence before development of the new

skill or learning can begin (Figs. 2 and 3).

16,17

Medical students in their final year and approach-

ing their specialty choice are frequently on this

rung of the ladder. As Dreyfus points out, when

the awareness of skill and deficiency is low or

nonexistent, the trainee or learner will simply not

see the need for learning.

15

It is essential to es-

tablish awareness of a weakness or training need

before attempting to impart or arrange training or

skills necessary to move trainees from stage 1 to

stage 2. Teachers and trainers commonly assume

trainees are at stage 2, and focus effort toward

achieving stage 3, when often trainees are still at

stage 1. This is a fundamental reason for the fail-

ure of a lot of training and teaching.

15

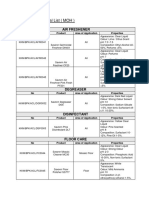

Table 1. Contrast between Novice and Expert Thinking*

Novice Expert

Inflexible (rule-bound, dogmatic) Flexible (adapt to circumstances)

Slow, hesitant, lacks confidence Fast, fluid, confident

Cannot access needed knowledge network quickly Instantly retrieves pertinent knowledge network

Emotions take over (seek stress reduction) Remains calm; does not act until necessary

Focus; addresses surface features of problem Focus; addresses source of problem

PET shows whole brain active PET shows part of brain active

Less than five experiences with similar problems More than five experiences with similar problems

Uses trial and error to solve Narrows down and rules out

Avoidance of premature closure/anchoring, faulty

synthesis, and omission

Does not jump to conclusions, recognizes A B C

syndrome, includes key data in decision making

PET, positron emission tomography.

*Data from Johnson P. The acquisition of skill. In: Smyth MM, Wing AM, eds. The Psychology of Human Movement. Orlando: Academic Press;

1984:215239; Druckman D, Bjork AR, eds. In the Minds Eye: Enhancing Human Performance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991;

Haier RJ, Siegel BV Jr, MacLachlan A, Soderling E, Lottenberg S, BuchsbaumMS. Regional glucose metabolic changes after learning a complex

visuospatial/motor task: A positron emission tomographic study. Brain Res. 1992;570:134143; and Voytovich AE, Rippey RM, Jue D. Diagnostic

reasoning in the multiproblem patient: An interactive, microcomputer-based audit. Eval Health Prof. 1986;9:90102.

Volume 130, Number 1 Nature of Novice and Expert Thinking

243

The goal for the unconscious incompetent

plastic surgeon is to build a knowledge network on

whichto place his or her newknowledge.

5,9,15

With-

out a framework, there is no place to put new facts

about diagnoses and treatment options. At the

same time that new nodes are being formed and

the fund of knowledge is increasing, the novice

surgeon is introduced to the basic tools of think-

ing like a plastic surgeon.

18

Before a learner can

recognize a pattern, there must be items present

that can be arranged and sorted, and rudimentary

processing algorithms available.

5,19

2: Conscious Incompetent (You Know That You

Do Not Know)

The postgraduate year2 plastic surgery resi-

dent is the classic example of someone on this

rung of the ladder (Fig. 4). At this level, the stu-

dents are beginning to realize that there is more

that they do not know than that which they do

know, and the more they learn, the greater their

realized ignorance becomes.

16

As a result, their

confidence drops.

17

This is a very uncomfortable

period, and residents in this stage can easily

become defensive.

20

Trainees can exist in this state for a long time,

depending on factors such as determination and

capacity to learn and the real extent to which an

individual is teachable. The teachers role in this

stage is tocome alongside the learner tosupport and

encourage.

15,21

The learner creates stress for himself

or herself. In wanting the resident to take on more

responsibility, the teacher must be careful tonot add

any stress other than that which the situation pro-

vides. The teacher can help the student make a

commitment to work through this difficult stage,

learn and apply the new plastic surgery concepts,

and move to the conscious competence stage.

18

The goal for the conscious incompetent plas-

tic surgeon is to begin to identify classic, common

Fig. 2. The developmental ladder. After explaining the rung, the chief character-

istics are identified, and key needs and areas to avoid are listed.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery July 2012

244

patterns and use well-established problem-solving

tools. The student still needs to add to the fund of

knowledge, but recognition of context and ability

to synthesize between knowledge nodes becomes

critical.

15

The learner is beginning to be able to see

common elements among ideas and skills that

seem disparate on the surface.

5

A catalog of anal-

ogous situations is begun.

5

As learners gain the

ability to recognize patterns, they should be given

at least one criterion-standard solutiona short-

cut, as it were.

18

A confident ability to make a

correct diagnosis, understand the disease, and

have a plan to treat the patient leads the maturing

plastic surgeon to the next rung.

3: Conscious Competent (You Know That You

Know)

At this stage, the increasingly able plastic sur-

geon acquires the new skills and knowledge of the

discipline much faster and more easily (Fig. 5).

The chief resident is frequently standing on this

rung. Here, the learner puts learning into practice

and gains confidence in carrying out the tasks or

jobs involved. The student is aware of his or her

new skills and works on refining them. The sur-

geon is still concentrating on the performance of

these activities, but with practice and experience,

these become increasingly automatic.

17

Becoming consciously competent often takes

a while, as the individual steadily learns about the

new area, through either experience or more for-

mal learning. This process can go in fits and starts

as the young plastic surgeon learns, forgets, pla-

teaus, and starts anew.

17

The more complex the

new area and the less natural talent present, the

longer this will take.

In this stage, the learner will need to concen-

trate and think to recall the knowledge or perform

the skill. The plastic surgeon is able to performthe

skill without assistance but is unlikely to be able to

teach it well to another person. The student must

continue to practice the new skill and commit to

becoming unconsciously competent, with prac-

tice being the single most effective way to move

from stage 3 to stage 4.

The goal for the conscious competent plastic

surgeon is to be able to recognize common pat-

terns easily, catalog analogies containing greater

variability, accrue an increasing number of short-

cuts, and develop specialized routines.

18,22

The

greatest danger is the rigid adherence to knowl-

edge, skills, and rules. Occasionally, the stress level

has to be raised to motivate the surgeon, who

knows that he knows, to keep learning.

5

Mastering

how a plastic surgeon thinks becomes more im-

portant than mastering what a plastic surgeon

knows; process begins to take precedence over

content.

19

4: Unconscious Competent (You Do Not Think

about Knowing)

Eventually, a plastic surgeon reaches the top

rung, the level where new skills become habits and

tasks are performed without conscious effort and

with automatic ease (Fig. 6).

17

This is the senior

staff surgeon. Johnson and Pratt note five charac-

teristics of a master plastic surgeon.

23

First, expert

surgeons possess great amounts of knowledge in

surgery and are able to apply that knowledge in

difficult practice settings. Second, the expert has

a well-organized, readily accessible knowledge net-

work that facilitates the acquisition of new infor-

mation. Third, expert plastic surgeons have well-

developed repertoires of strategies for acquiring

new knowledge, integrating and organizing their

networks, and applying their knowledge in a va-

riety of contexts. Fourth, an expert is motivated to

Fig. 3. The unconscious incompetent learner.

Fig. 4. The conscious incompetent learner.

Volume 130, Number 1 Nature of Novice and Expert Thinking

245

continue to learn and increase mastery. Fifth, the

unconsciously competent plastic surgeons appear

tobe able toaccess actions, recognitions, andjudg-

ments spontaneously during their performance,

often unaware of having learned to do these

things, and usually unable to describe all of the

details of how they are able to accomplish the task.

The expert is intuitive; pattern recognition

and matching occur on a subconscious level. As a

result, the person might be able to teach others in

the skill concerned, although after some time of

being unconsciously competent, the expert might

actually have difficulty in explaining howhe or she

does itthe skill has become largely instinctual.

18

This gives rise to the need for long-standing un-

conscious competence to be checked periodically

against new standards.

24

CLIMBING THE LADDER

Learning activities should be structured to be

suitable for the stage of the learner. The novice

learner should be given ample opportunity to

watch experts and ask questions.

25

Answering a

question with a question is not helpful at this stage

but will become more so as the student gains a

greater fund of knowledge.

18

Journal club, where

the emphasis is on discussing the latest informa-

tion, is not very helpful to someone who has yet to

understand the basics. Simulations and case man-

agement scenarios will help unconscious incom-

petent learners become conscious of what they

need to know; the opportunity to play surgeon

will motivate the beginner to move forward.

18,26

The conscious incompetent learner should be

given hands-on experience with basic patients and

techniques.

15

Complex clinical scenarios should

be broken down into more basic components and

the learner given simple problems to solve.

18

The

focus should be on the facts, concepts, and tech-

niques that the plastic surgeon in training must

know. Students should be asked to discriminate be-

tween correct and incorrect information and ac-

tions. Classic presentations should be emphasized.

18

This is in contrast to the conscious competent

surgeon, who needs to be challenged with unusual

presentations and more autonomy, moving from

direct to indirect supervision.

18

Journal club is

helpful at this stage; morbidity and mortality con-

ferences remind the mature surgeon that there is

still more to be learned.

27

The unconsciously com-

petent surgeon is ready to begin by developing

learning activities and partaking inpeer-group dis-

cussion. By taking on the responsibility of teach-

ing, the master plastic surgeon is forced to think

through the steps of knowing, and challenged to

stay current in plastic surgery.

As teachers, it is important to ask questions

appropriate for the learners stage. Helpful ques-

tions for the unconscious incompetent learner are

the who, what, where, andwhen questions.

26

The

questions should be about the fundamental facts

and principles of plastic surgery.

5

When a budding

plastic surgeon asks a question, it should be an-

swered fully and then the novice should be en-

couraged to read more about it.

18

It is also helpful

to think out loud and show the learner how the

answer is derived.

18

Questions about why and

differential diagnoses begin to show the context

for the facts and help the learner move to the next

stage.

Questioning the conscious incompetent learner

requires tact. The teaching surgeonshould establish

a safe environment for questions and reassure the

resident of the purpose of the questioning.

17

The

conscious incompetent learner is best helped with

comparison and contrast inquiries. Learners in

this stage should be asked to make decisions and

Fig. 5. The conscious competent learner.

Fig. 6. The unconscious competent learner.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery July 2012

246

justify them. What if questions are excellent to

begin to move the learner to the conscious com-

petent stage. This resident shouldalsobe askedfor

backup plans and exceptions to the rule.

17

The

surgeon at this stage should be given questions

for which the answer violates well-established

patterns.

5

A helpful question for the unconscious

competent learner is, Howwould you explain this

to someone else?

Patience is the watchword for practitioners on

all rungs of the ladder. On one hand, it is impor-

tant for plastic surgeons on the first three rungs to

consciously bring to mind the fact that progress

takes time. The knowledge and skills they see dem-

onstrated are the result of significant time spent

learning. On the other hand, the senior plastic

surgeon must remember to be patient with those

who are now climbing the rungs he or she stood

on a short while ago.

AT THE TOP

Although mastery of plastic surgery is the goal

of every novice, perfection is not possible. As a

result, we spend our lives as both teacher and

student simultaneously. The senior surgeons re-

sponsibility is to fuel the enthusiasm of the un-

consciously incompetent, soothe the insecurities

of the consciously incompetent, loosenthe rigidity

of the consciously competent, and engage the wis-

dom of the unconsciously competent. The chal-

lenge is to stand on the top rung, steady and firm,

so that the plastic surgeons after us can use our

shoulders as the next rung and see farther than

we can.

Robert A. Weber, M.D.

Scott & White Healthcare

2401 South 31st Street

Temple, Texas 76508

rweber@swmail.sw.org

REFERENCES

1. Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert

performance: A general overview. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:

988994.

2. Norman GR, Brooks LR, Cunnington JP, Shali V, Marriott M,

Regehr G. Expert-novice differences in the use of history and

visual information from patients. Acad Med. 1996;71:S62

S64.

3. Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diag-

nostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:22172225.

4. Regehr G, Norman GR. Issues in cognitive psychology: Im-

plications for professional education. Acad Med. 1996;71:

9881001.

5. Carraccio CL, Benson BJ, Nixon LJ, Derstine PL. From the

educational bench to the clinical bedside: Translating the

Dreyfus developmental model to the learning of clinical

skills. Acad Med. 2008;83:761767.

6. Gigerenzer G. Less is more in health care. In: Gut Feelings: The

Intelligence of the Unconscious. New York: Penguin Books; 2008:

158178.

7. Hodges B, Regehr G, Martin D. Difficulties in recognizing

ones own incompetence: Novice physicians who are un-

skilled and unaware of it. Acad Med. 2001;76:S87S89.

8. Johnson P. The acquisition of skill. In: Smyth MM, Wing AM,

eds. The Psychology of Human Movement. Orlando: Academic

Press; 1984:215239.

9. Druckman D, Bjork AR, eds. In the Minds Eye: Enhancing

Human Performance. Washington, DC: National Academy

Press; 1991.

10. Haier RJ, Siegel BV Jr, MacLachlan A, Soderling E, Lotten-

berg S, Buchsbaum MS. Regional glucose metabolic changes

after learning a complex visuospatial/motor task: A positron

emission tomographic study. Brain Res. 1992;570:134143.

11. Voytovich AE, Rippey RM, Jue D. Diagnostic reasoning in the

multiproblem patient: An interactive, microcomputer-based

audit. Eval Health Prof. 1986;9:90102.

12. Chi CTH, Glaser R, Farr MJ, eds. Chapter 1. In: The Nature

of Expertise. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1988:1528.

13. Pangaro LN. A shared professional framework for anatomy

and clinical clerkships. Clin Anat. 2006;19:419428.

14. Dreyfus HL. What Computers Cant Do: A Critique of Artificial

Reason. New York: Harper & Row; 1972 (Paperback edition,

1979).

15. Dreyfus S, Dreyfus H. A Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities

Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition. Berkeley, Calif: Opera-

tions Research Centre, California University, Berkeley; 1980.

16. Howell WS. The Empathic Communicator. Belmont, Calif:

Wadsworth; 1982:2933.

17. Peyton JWR. The learning cycle. In: Peyton JWR, ed. Teaching

& Learning in Medical Practice. Rickmansworth, United King-

dom: Manticore Europe Ltd; 1998:1319.

18. Gookin J. Coaching for competence. In: 2004 NOLS Leader-

ship Educator Notebook. Lander, Wyo: National Outdoor Lead-

ership School; 2008:57.

19. Schon DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass; 1987.

20. Perry WG. Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the

College Years: A Scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Win-

ston; 1970.

21. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82:402

407.

22. Mylopoulos M, Regehr G. How student models of expertise

and innovation impact the development of adaptive exper-

tise in medicine. Med Educ. 2009;43:127132.

23. Johnson J, Pratt DD. The apprenticeship perspective: Mod-

elling ways of being. In: Pratt DD, et al., eds. Five Perspectives

on Teaching in Adult and Higher Education. Malabar, Fla:

Kreiger; 2005:83103.

24. Mylopoulos M, Regehr G. Cognitive metaphors of expertise

and knowledge: Prospects and limitations for medical edu-

cation. Med Educ. 2007;41:11591165.

25. Lake FR, Hamdorf JM. Teaching on the run tips 5: Teaching

a skill. Med J Aust. 2004;181:327328.

26. Wales CE, Nardi AH, Stager RA. Emphasizing critical think-

ing and problem solving skills. In: Curry L, Wergin JF, eds.

Educating Professionals. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993:178

211.

27. Peyton R. Journal clubs and critical reading. In: Peyton JWR,

ed. Teaching & Learning in Medical Practice. Rickmansworth,

United Kingdom: Manticore Europe Ltd; 1998:131137.

Volume 130, Number 1 Nature of Novice and Expert Thinking

247

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Practical Skills On PalpationDokumen6 halamanPractical Skills On PalpationsudersonBelum ada peringkat

- Massry - Management of Postblepharoplasty Lower Eyelid RetractionDokumen10 halamanMassry - Management of Postblepharoplasty Lower Eyelid RetractionLuiggi Fayad100% (1)

- Ethnic and Gender Considerations in The Use of Facial Injectables: Male PatientsDokumen4 halamanEthnic and Gender Considerations in The Use of Facial Injectables: Male PatientsLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Uptime Elements Passport: GineerDokumen148 halamanUptime Elements Passport: GineerBrian Careel94% (16)

- Nanofat Grafting Basic Research and ClinicalDokumen10 halamanNanofat Grafting Basic Research and ClinicalLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Sino-Japanese Haikai PDFDokumen240 halamanSino-Japanese Haikai PDFAlina Diana BratosinBelum ada peringkat

- Rhinoplasty Dissection ManualDokumen185 halamanRhinoplasty Dissection ManualVikas Vats100% (3)

- Q&A JurisdictionDokumen20 halamanQ&A JurisdictionlucasBelum ada peringkat

- Nanofat Grafting Basic Research and Clinical.53Dokumen10 halamanNanofat Grafting Basic Research and Clinical.53Luiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Components of CompetencyDokumen4 halamanComponents of Competencydmnd_cd67% (3)

- MastopexyDokumen15 halamanMastopexyLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Research Clinical Instructors RevisedDokumen28 halamanResearch Clinical Instructors RevisedKateMighty AgbalogBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical TeachingDokumen48 halamanClinical TeachingAmy Roc100% (2)

- Teaching Psychomotor SkillsDokumen4 halamanTeaching Psychomotor SkillsChuche Marie TumarongBelum ada peringkat

- SJT Curriculum Report Incl AppendicesDokumen34 halamanSJT Curriculum Report Incl AppendicesJ KareemBelum ada peringkat

- Bloom's Taxonomy - From Knowledge To Practice: Josette Akresh-Gonzales, Editorial Systems Manager, NEJM Group EducationDokumen5 halamanBloom's Taxonomy - From Knowledge To Practice: Josette Akresh-Gonzales, Editorial Systems Manager, NEJM Group EducationVvadaHottaBelum ada peringkat

- Frameworks For Learner Assessment in Medicine AMEE Guide No 78Dokumen15 halamanFrameworks For Learner Assessment in Medicine AMEE Guide No 78achciaBelum ada peringkat

- Student Nurse CourseworkDokumen4 halamanStudent Nurse Courseworkshvfihdjd100% (2)

- AMEE Guide Theories Used in AssessmentDokumen15 halamanAMEE Guide Theories Used in AssessmentalmoslihBelum ada peringkat

- Nurs 7723 - Worksheet 1Dokumen3 halamanNurs 7723 - Worksheet 1api-643881078Belum ada peringkat

- MESE-058: Qualitative ApproachDokumen9 halamanMESE-058: Qualitative ApproachAakashMalhotraBelum ada peringkat

- Finlas - Chapter 9 - 10 - Diaz, Cherry Lou. Bsn1aDokumen3 halamanFinlas - Chapter 9 - 10 - Diaz, Cherry Lou. Bsn1aKing Aldus ConstantinoBelum ada peringkat

- Debriefing What Is Debriefing?: Bs Psychology 4-2Dokumen9 halamanDebriefing What Is Debriefing?: Bs Psychology 4-2Jhanine DavidBelum ada peringkat

- Epstein 2007 Assessmentin Medical EducationDokumen11 halamanEpstein 2007 Assessmentin Medical Educationwedad jumaBelum ada peringkat

- Dreyfus Five-Stage Model of Adult Skills Acquisition Applied To Engineering LifelDokumen13 halamanDreyfus Five-Stage Model of Adult Skills Acquisition Applied To Engineering LifelbneckaBelum ada peringkat

- Design and Implementation of A Computerised Career Guidance Information SystemDokumen46 halamanDesign and Implementation of A Computerised Career Guidance Information SystemAkinyele deborahBelum ada peringkat

- Apta Professional Behaviors Plan-CarlisleDokumen20 halamanApta Professional Behaviors Plan-Carlisleapi-623105677Belum ada peringkat

- TrotterDokumen5 halamanTrotterNurulBelum ada peringkat

- Health Education ProcessDokumen39 halamanHealth Education ProcessLanzen DragneelBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter A2 How Professionals Learn Through WorkDokumen28 halamanChapter A2 How Professionals Learn Through WorkBushra AliBelum ada peringkat

- Canadian Ota Pta Fieldwork Evaluation Form - Durham College - 2017-2018 Copy 2Dokumen12 halamanCanadian Ota Pta Fieldwork Evaluation Form - Durham College - 2017-2018 Copy 2api-387804028Belum ada peringkat

- Successfully Navigating The Stages of Doc StagesDokumen13 halamanSuccessfully Navigating The Stages of Doc StagesIrina Andra TacheBelum ada peringkat

- Psycho Metric AnalysisDokumen6 halamanPsycho Metric AnalysisLeena SagayanathanBelum ada peringkat

- Coursework RationaleDokumen8 halamanCoursework Rationaledkcvybifg100% (2)

- NI Module 2 TheoriesDokumen17 halamanNI Module 2 TheoriespnlgnkrstnBelum ada peringkat

- Apta Professional Behaviors PlanDokumen31 halamanApta Professional Behaviors Planapi-557944670Belum ada peringkat

- Learning Zone: Using Coaching Interventions To Develop Clinical SkillsDokumen9 halamanLearning Zone: Using Coaching Interventions To Develop Clinical Skillsloim2301Belum ada peringkat

- Case Teaching and Evaluation - PattonDokumen10 halamanCase Teaching and Evaluation - PattonKees WesterdijkBelum ada peringkat

- Revised Chapter 1Dokumen5 halamanRevised Chapter 1cha mcbBelum ada peringkat

- Apta Professional Behaviors Plan 3Dokumen22 halamanApta Professional Behaviors Plan 3api-640939939Belum ada peringkat

- Professional Behaviors Assessment FinalDokumen31 halamanProfessional Behaviors Assessment Finalapi-623335773Belum ada peringkat

- Apta Professional Behaviors PlanDokumen26 halamanApta Professional Behaviors Planapi-487110724Belum ada peringkat

- Clinical Experiences of Third Year Nursing Students of Lorma CollegesDokumen10 halamanClinical Experiences of Third Year Nursing Students of Lorma CollegesKarissa Joyce Eslao DiazBelum ada peringkat

- Apta Professional Behaviors Plan PTP 3Dokumen20 halamanApta Professional Behaviors Plan PTP 3api-703723590Belum ada peringkat

- Zeeshan Gull RG No HDA UNIT Unit 06 Task WorkDokumen9 halamanZeeshan Gull RG No HDA UNIT Unit 06 Task WorkHaider KhanBelum ada peringkat

- Competence, Proficiency and BeyondDokumen7 halamanCompetence, Proficiency and BeyondposthocBelum ada peringkat

- 1Dokumen161 halaman1mohamedfisalBelum ada peringkat

- Md1projp2hillj RevisedDokumen14 halamanMd1projp2hillj Revisedapi-287940912Belum ada peringkat

- Thesis Entitled "Degree of Competency of Nursing Students in The Implementation of Ethical Guidelines For Nursing Practice"Dokumen43 halamanThesis Entitled "Degree of Competency of Nursing Students in The Implementation of Ethical Guidelines For Nursing Practice"Saro BalberanBelum ada peringkat

- Edu 515 UnitsDokumen15 halamanEdu 515 Unitsapi-385487853Belum ada peringkat

- Pending Thesis DefenceDokumen7 halamanPending Thesis DefencePaperWritingWebsitePalmBay100% (2)

- 1Dokumen46 halaman1Gia AtayBelum ada peringkat

- Guidance and Counselling AnswersDokumen26 halamanGuidance and Counselling Answersdipayan bhattacharyaBelum ada peringkat

- Med/Ed Enews v3 No. 06 (MAY 2015)Dokumen13 halamanMed/Ed Enews v3 No. 06 (MAY 2015)KC Spear Ellinwood, former Director Instructional DevelopmentBelum ada peringkat

- Vision VAM 2020 (Ethics) Guide To Handle Case StudiesDokumen21 halamanVision VAM 2020 (Ethics) Guide To Handle Case StudiesRohan Pratap SinghBelum ada peringkat

- Paz RelatedDokumen9 halamanPaz RelatedMark Joseph Felicitas CuntapayBelum ada peringkat

- Literature Review On Mentorship in NursingDokumen7 halamanLiterature Review On Mentorship in Nursingafmzqlbvdfeenz100% (1)

- TOK Presentation CommentsDokumen8 halamanTOK Presentation CommentselniniodipaduaBelum ada peringkat

- How To Teach Practical SkillsDokumen2 halamanHow To Teach Practical SkillsRauza TunnurBelum ada peringkat

- Fandral SlidesManiaDokumen25 halamanFandral SlidesManiaSarina ServanoBelum ada peringkat

- Dissertation Interim Report ExampleDokumen8 halamanDissertation Interim Report ExampleCustomPapersOnlineUK100% (1)

- Reflection - Health Education - Ferry, John Kenley DBDokumen8 halamanReflection - Health Education - Ferry, John Kenley DBJohn Kenley FerryBelum ada peringkat

- A New Vocabulary and Other InnovationsDokumen14 halamanA New Vocabulary and Other Innovationsrpascua123Belum ada peringkat

- Applied Communication: by Moses I Irukan. 12/ 04/ 2019Dokumen111 halamanApplied Communication: by Moses I Irukan. 12/ 04/ 2019Jonah nyachaeBelum ada peringkat

- Emergency Medicine Dissertation TopicsDokumen8 halamanEmergency Medicine Dissertation TopicsBuyCollegePaperSingapore100% (1)

- Assessing Learning Needs of Nursing Staff Jesson PlantasDokumen4 halamanAssessing Learning Needs of Nursing Staff Jesson PlantasMarjorie PacatanBelum ada peringkat

- WK Wiki TableDokumen6 halamanWK Wiki Tableapi-312750675Belum ada peringkat

- Research Paper ImplicationsDokumen6 halamanResearch Paper Implicationsuziianwgf100% (1)

- StainsDokumen1 halamanStainsLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Harvesting Rib Cartilage Grafts For Secondary Rhinoplasty: Background: MethodsDokumen7 halamanHarvesting Rib Cartilage Grafts For Secondary Rhinoplasty: Background: MethodsLuiggi Fayad100% (1)

- Annals of Plastic and Reconstructive SurgeryDokumen10 halamanAnnals of Plastic and Reconstructive SurgeryLuiggi Fayad100% (2)

- A Surgical Solution To The Deep Nasolabial Fold - Lassus, Claude 2nd PartDokumen3 halamanA Surgical Solution To The Deep Nasolabial Fold - Lassus, Claude 2nd PartLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- How To Write An Abstract That Will Be Accepted For Presentation at A National MeetingDokumen7 halamanHow To Write An Abstract That Will Be Accepted For Presentation at A National MeetingLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline - Reduction MammaplastyDokumen16 halamanEvidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline - Reduction MammaplastyLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Lateral Calcaneal Artery Skin FlapDokumen8 halamanLateral Calcaneal Artery Skin FlapLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- How To Write An Abstract That Will Be Accepted For Presentation at A National MeetingDokumen7 halamanHow To Write An Abstract That Will Be Accepted For Presentation at A National MeetingLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- How To Write A World-Class PaperDokumen93 halamanHow To Write A World-Class PaperLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- ABThera MonographDokumen32 halamanABThera MonographLuiggi FayadBelum ada peringkat

- Prepositions French Worksheet For PracticeDokumen37 halamanPrepositions French Worksheet For Practiceangelamonteiro100% (1)

- Espinosa - 2016 - Martín Ramírez at The Menil CollectionDokumen3 halamanEspinosa - 2016 - Martín Ramírez at The Menil CollectionVíctor M. EspinosaBelum ada peringkat

- Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageDokumen11 halamanChildbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageWenny Indah Purnama Eka SariBelum ada peringkat

- Need You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryDokumen3 halamanNeed You Now Lyrics: Charles Scott, HillaryAl UsadBelum ada peringkat

- AASW Code of Ethics-2004Dokumen36 halamanAASW Code of Ethics-2004Steven TanBelum ada peringkat

- Gandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage IndiaDokumen6 halamanGandhi Was A British Agent and Brought From SA by British To Sabotage Indiakushalmehra100% (2)

- 221-240 - PMP BankDokumen4 halaman221-240 - PMP BankAdetula Bamidele OpeyemiBelum ada peringkat

- Indg 264.3 w02Dokumen15 halamanIndg 264.3 w02FrauBelum ada peringkat

- Poet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry PDokumen3 halamanPoet Forugh Farrokhzad in World Poetry Pkarla telloBelum ada peringkat

- CIP Program Report 1992Dokumen180 halamanCIP Program Report 1992cip-libraryBelum ada peringkat

- 576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Dokumen15 halaman576 1 1179 1 10 20181220Sana MuzaffarBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Instrumented IndentationDokumen7 halamanIntroduction To Instrumented Indentationopvsj42Belum ada peringkat

- Romanian Oil IndustryDokumen7 halamanRomanian Oil IndustryEnot SoulaviereBelum ada peringkat

- Julie Jacko - Professor of Healthcare InformaticsDokumen1 halamanJulie Jacko - Professor of Healthcare InformaticsjuliejackoBelum ada peringkat

- British Citizenship Exam Review TestDokumen25 halamanBritish Citizenship Exam Review TestMay J. PabloBelum ada peringkat

- Approved Chemical ListDokumen2 halamanApproved Chemical ListSyed Mansur Alyahya100% (1)

- Practice Test 4 For Grade 12Dokumen5 halamanPractice Test 4 For Grade 12MAx IMp BayuBelum ada peringkat

- K9G8G08B0B SamsungDokumen43 halamanK9G8G08B0B SamsungThienBelum ada peringkat

- Producto Académico #2: Inglés Profesional 2Dokumen2 halamanProducto Académico #2: Inglés Profesional 2fredy carpioBelum ada peringkat

- Serological and Molecular DiagnosisDokumen9 halamanSerological and Molecular DiagnosisPAIRAT, Ella Joy M.Belum ada peringkat

- Philosophy of Education SyllabusDokumen5 halamanPhilosophy of Education SyllabusGa MusaBelum ada peringkat

- Win Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsDokumen11 halamanWin Tensor-UserGuide Optimization FunctionsadetriyunitaBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan Pumpkin Moon SandDokumen3 halamanLesson Plan Pumpkin Moon Sandapi-273177086Belum ada peringkat

- Re CrystallizationDokumen25 halamanRe CrystallizationMarol CerdaBelum ada peringkat

- Proper AdjectivesDokumen3 halamanProper AdjectivesRania Mohammed0% (2)

- Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12 Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12Dokumen55 halamanCreative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12 Creative Nonfiction 2 For Humss 12QUINTOS, JOVINCE U. G-12 HUMSS A GROUP 8Belum ada peringkat

- Enunciado de La Pregunta: Finalizado Se Puntúa 1.00 Sobre 1.00Dokumen9 halamanEnunciado de La Pregunta: Finalizado Se Puntúa 1.00 Sobre 1.00Samuel MojicaBelum ada peringkat