Confu

Diunggah oleh

Erika ArbolerasHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Confu

Diunggah oleh

Erika ArbolerasHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

INTRODUCTION

Some say Confucianism is not a religion, since there are no Confucian deities and

no teachings about the afterlife. Confucius himself was a staunch supporter of

ritual, however, and for many centuries there were state rituals associated with

Confucianism. Most importantly, the Confucian tradition was instrumental in

shaping Chinese social relationships and moral thought. Thus even without deities

and a vision of salvation, Confucianism plays much the same role as religion does

in other cultural contexts. The founder of Confucianism was Kong Qiu (K'ung

Ch'iu), who was born around 552 B.C.E. in the small state of Lu and died in

479 B.C.E. The Latinized name Confucius, based on the honorific title Kong Fuzi

(K'ung Fu-tzu), was created by 16th-century Jesuit missionaries in China.

Confucius was a teacher to sons of the nobility at a time when formal education

was just beginning in China. He traveled from region to region with a small group

of disciples, a number of whom would become important government officials.

Confucius was not particularly famous during his lifetime, and even considered

himself to be a failure. He longed to be the advisor to a powerful ruler, and he

believed that such a ruler, with the right advice, could bring about an ideal

world. Confucius said heaven and the afterlife were beyond human capacity to

understand, and one should therefore concentrate instead on doing the right

thing in this life. The earliest records from his students indicate that he did not

provide many moral precepts; rather he taught an attitude toward one's fellow

humans of respect, particularly respect for one's parents, teachers, and elders.

He also encouraged his students to learn from everyone they encountered and to

honor others' cultural norms. Later, his teachings would be translated by

authoritarian political philosophers into strict guidelines, and for much of Chinese

history Confucianism would be associated with an immutable hierarchy of

authority and unquestioning obedience.

HISTORY

Confucianism is an ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings

of the Chinese philosopher Confucius ( Kng Fz, or K'ung-fu-tzu, lit.

"Master Kong", 551479 BC). Confucianism originated as an "ethical-sociopolitical

teaching" during theSpring and Autumn Period, but later developed metaphysical

and cosmological elements in the Han Dynasty.

[1]

Following the abandonment

of Legalism in China after the Qin Dynasty, Confucianism became the official

state ideology of the Han. The disintegration of the Han in the second century

C.E. opened the way for the spiritual and otherworldly doctrines

of Buddhism and Daoism to dominate intellectual life and to become the ruling

doctrines during the Tang dynasty. In the late Tang, Confucianism absorbed many

of these challenging aspects and was reformulated Neo-Confucianism. This

reinvigorated form was adopted as the basis of the imperial exams and the core

philosophy of the scholar official class in the Song dynasty. Neo-Confucianism

turned into sometimes rigid orthodoxy over the following centuries. In popular

practice, however, the three doctrines of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism

were often melded together. The abolition of the examination system in 1905

marked the end of official Confucianism. The New Culture intellectuals of the

early twentieth century blamed Confucianism for China's weaknesses. They

searched for imported doctrines to replace it, such as the "Three Principles of

the People" with the establishment of the Republic of China, and

then Communism under the People's Republic of China. In the late twentieth

century, Confucianism was credited with the rise of the East Asian economy and

revived both in the People's Republic and abroad.

The core of Confucianism is humanism, or what the philosopher Herbert

Fingarette calls "the secular as sacred." The focus of spiritual concern is this

world and the family, not the gods and not the afterlife.

[2]

Confucianism

broadly speaking does not exalt faithfulness to divine will or higher law.

[3]

This

stance rests on the belief that human beings are teachable, improvable and

perfectible through personal and communal endeavor especially self-cultivation and

self-creation. Confucian thought focuses on the cultivation of virtue and

maintenance of ethics, the most basic of which are ren, yi, and li.

[4]

Ren is an

obligation ofaltruism and humaneness for other individuals within a

community, yi is the upholding of righteousness and the moral disposition to do

good, and li is a system of norms andpropriety that determines how a person

should properly act within a community.

[4]

Confucianism holds that one should

give up one's life, if necessary, either passively or actively, for the sake of

upholding the cardinal moral values of ren and yi.

[5]

Cultures and countries strongly influenced by Confucianism include

mainland China,Taiwan, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, as well as various territories

settled predominantly by Chinese people, such as Singapore. Although Confucian

ideas prevail in these areas, few people identify themselves as Confucian,

[6]

and

instead see Confucian ethics as a complementary guideline for other ideologies and

beliefs,

including democracy,

[7]

Marxism,

[8]

capitalism,

[9]

Christianity,

[10]

Islam

[11]

and Buddhis

m.

BELIEFS AND TRADITIONS

Traditionally, Confucius was thought to be the author or editor of the Five

Classics which were the basic texts of Confucianism. The scholar Yao

Xinzhong allows that there are good reasons to believe that Confucian classics

took shape in the hands of Confucius, but that nothing can be taken for

granted in the matter of the early versions of the classics. Yao reports that

perhaps most scholars today hold the pragmatic view that Confucius and his

followers, although they did not intend to create a system of classics,

contributed to their formation. In any case, it is undisputed that for most of

the last 2,000 years, Confucius was believed to have either written or edited

these texts.

[15]

The scholar Tu Wei-ming explains these classics as embodying five visions" which

underlie the development of Confucianism:

I Ching or Classic of Change or Book of Changes, generally held to be the

earliest of the classics, shows a metaphysical vision which combines divinatory

art with numerological technique and ethical insight; philosophy of change sees

cosmos as interaction between the two energies yin and yang, universe always

shows organismic unity and dynamism.

Classic of Poetry or Book of Songs is the earliest anthology of Chinese

poems and songs. It shows the poetic vision in the belief that poetry and

music convey common human feelings and mutual responsiveness.

Book of Documents or Book of History Compilation of speeches of major

figures and records of events in ancient times embodies the political vision

and addresses the kingly way in terms of the ethical foundation for humane

government. The documents show the sagacity, filial piety, and work ethic of

Yao, Shun, and Yu. They established a political culture which was based on

responsibility and trust. Their virtue formed a covenant of social harmony

which did not depend on punishment or coercion.

Book of Rites describes the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites

of the Zhou Dynasty. This social vision defined society not as an adversarial

system based on contractual relations but as a community of trust based on

social responsibility. Thefour functional occupations are cooperative (farmer,

scholar, artisan, merchant).

Spring and Autumn Annals chronicles the period to which it gives its

name, Spring and Autumn Period (771-476 BCE) and these events emphasize

the significance of collective memory for communal self-identification, for

reanimating the old is the best way to attain the new.

[16]

Ren

Main article: Ren (Confucianism)

Ren is one of the basic virtues promoted by Confucius, and is an obligation

of altruism and humaneness for other individuals within a

community.

[4]

Confucius' concept of humaneness (Chinese: ; pinyin: rn) is

probably best expressed in the Confucian version of theethic of reciprocity, or

the Golden Rule: "Do not do unto others what you would not have them do

unto you."

Confucius never stated whether man was born good or evil,

[19]

noting that 'By

nature men are similar; by practice men are wide apart'

[20]

implying that

whether good or bad, Confucius must have perceived all men to be born with

intrinsic similarities, but that man is conditioned and inuenced by study and

practise. Xunzi's opinion is that men originally just want what they instinctively

want despite positive or negative results it may bring, so cultivation is needed.

In Mencius' view, all men are born to share goodness such as compassion and

good heart, although they may become wicked. The Three Character

Classic begins with "People at birth are naturally good (kind-hearted)", which

stems from Mencius' idea. All the views eventually lead to recognize the

importance of human education and cultivation.

Rn also has a political dimension. If the ruler lacks rn, Confucianism holds, it

will be difficult if not impossible for his subjects to behave humanely. Rn is the

basis of Confucian political theory: it presupposes an autocratic ruler, exhorted

to refrain from acting inhumanely towards his subjects. An inhumane ruler runs

the risk of losing the "Mandate of Heaven", the right to rule. A ruler lacking

such a mandate need not be obeyed. But a ruler who reigns humanely and takes

care of the people is to be obeyed strictly, for the benevolence of his dominion

shows that he has been mandated by heaven. Confucius himself had little to say

on the will of the people, but his leading follower Mencius did state on one

occasion that the people's opinion on certain weighty matters should be

considered.

Etiquette

Main article: Li (Confucianism)

In Confucianism, the term "li" (Chinese: ; pinyin: l), sometimes translated

into English as rituals, customs, rites, etiquette, or morals, refers to any of the

secular social functions of daily life, akin to the Western term for culture.

Confucius considered education and music as various elements of li. Li were

codified and treated as a comprehensive system of norms, guiding

the propriety or politeness which colors everyday life. Confucius himself tried to

revive the etiquette of earlier dynasties.

It is important to note that, although li is sometimes translated as "ritual" or

"rites", it has developed a specialized meaning in Confucianism, as opposed to its

usual religious meanings. In Confucianism, the acts of everyday life are considered

rituals. Rituals are not necessarily regimented or arbitrary practices, but the

routines that people often engage in, knowingly or unknowingly, during the

normal course of their lives. Shaping the rituals in a way that leads to a

content and healthy society, and to content and healthy people, is one purpose

of Confucian philosophy.

Loyalty

Loyalty (Chinese: ; pinyin: zhng) is the equivalent of filial piety on a

different plane. It is particularly relevant for the social class to which most of

Confucius' students belonged, because the only way for an ambitious young

scholar to make his way in the Confucian Chinese world was to enter a ruler's

civil service. Like filial piety, however, loyalty was often subverted by the

autocratic regimes of China. Confucius had advocated a sensitivity to

the realpolitik of the class relations in his time; he did not propose that "might

makes right", but that a superior who had received the "Mandate of Heaven"

(see below) should be obeyed because of his moral rectitude.

In later ages, however, emphasis was placed more on the obligations of the ruled

to the ruler, and less on the ruler's obligations to the ruled.

Loyalty was also an extension of one's duties to friends, family, and spouse.

Loyalty to one's family came first, then to one's spouse, then to one's ruler,

and lastly to one's friends. Loyalty was considered one of the greater human

virtues.

Confucius also realized that loyalty and filial piety can potentially conflict.

Filial piety

Main article: Filial piety

"Filial piety" (Chinese: ; pinyin: xio) is considered among the greatest of

virtues and must be shown towards both the living and the dead (including even

remote ancestors). The term "filial" (meaning "of a child") characterizes the

respect that a child, originally a son, should show to his parents. This

relationship was extended by analogy to a series of five

relationships (Chinese: ; pinyin:wln):

[21]

The Five Bonds

Ruler to Ruled

Father to Son

Husband to Wife

Elder Brother to Younger Brother

Friend to Friend

Specific duties were prescribed to each of the participants in these sets of

relationships. Such duties were also extended to the dead, where the living stood

as sons to their deceased family. This led to the veneration of ancestors. The

only relationship where respect for elders wasn't stressed was the Friend to

Friend relationship. In all other relationships, high reverence was held for elders.

The idea of Filial piety influenced the Chinese legal system: a criminal would be

punished more harshly if the culprit had committed the crime against a parent,

while fathers often exercised enormous power over their children. A similar

differentiation was applied to other relationships. Now

[PROC? clarification needed]

filial

piety is also built into law. People have the responsibility to provide for their

elderly parents according to the law.

The main source of our knowledge of the importance of filial piety is the Classic

of Filial Piety, a work attributed to Confucius and his son but almost certainly

written in the 3rd century BCE. The Analects, the main source of the

Confucianism of Confucius, actually has little to say on the matter of filial piety

and some sources believe the concept was focused on by later thinkers as a

response toMohism.

Filial piety has continued to play a central role in Confucian thinking to the

present day.

Relationships

Relationships are central to Confucianism. Particular duties arise from one's

particular situation in relation to others. The individual stands simultaneously in

several different relationships with different people: as a junior in relation to

parents and elders, and as a senior in relation to younger siblings, students, and

others. While juniors are considered in Confucianism to owe their seniors

reverence, seniors also have duties of benevolence and concern toward juniors.

This theme of mutuality is prevalent in East Asian cultures even to this day.

Social harmonythe great goal of Confucianismtherefore results in part from

every individual knowing his or her place in the social order, and playing his or

her part well. When Duke Jing of Qi asked about government, by which he

meant proper administration so as to bring social harmony, Confucius replied:

There is government, when the prince is prince, and the minister is minister;

when the father is father, and the son is son. (Analects XII, 11, trans. Legge)

Mencius says: "When being a child, yearn for and love your parents; when

growing mature, yearn for and love your lassie; when having wife and child(ren),

yearn for and love your wife and child(ren); when being an official (or a

staffer), yearn for and love your sovereign (and/or boss)."

[22][this quote needs a citation]

The gentleman

Main article: Junzi

The term jnz (Chinese: ; literally "lord's child") is crucial to classical

Confucianism. Confucianism exhorts all people to strive for the ideal of a

"gentleman" or "perfect man". A succinct description of the "perfect man" is

one who "combines the qualities of saint, scholar, and gentleman." In modern

times the masculine translation in English is also traditional and is still

frequently used. Elitismwas bound up with the concept, and gentlemen were

expected to act as moral guides to the rest of society.

They were to:

cultivate themselves morally;

show filial piety and loyalty where these are due;

cultivate humanity, or benevolence.

The great exemplar of the perfect gentleman is Confucius himself. Perhaps the

tragedy of his life was that he was never awarded the high official position which

he desired, from which he wished to demonstrate the general well-being that

would ensue if humane persons ruled and administered the state.

The opposite of the Jnz was the Xiorn (Chinese: ; pinyin: xi orn;

literally "small person"). The character in this context means petty in mind

and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, or materialistic.

Rectification of names

Main article: Rectification of Names

Confucius believed that social disorder often stemmed from failure to perceive,

understand, and deal with reality. Fundamentally, then, social disorder can stem

from the failure to call things by their proper names, and his solution to this

was Zhngmng (Chinese: [];pinyin: zhngmng; literally "rectification of

terms"). He gave an explanation of zhengming to one of his disciples.

Zi-lu said, "The vassal of Wei has been waiting for you, in order with you to

administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?"

The Master replied, "What is necessary to rectify names."

"So! indeed!" said Zi-lu. "You are wide off the mark! Why must there be such

rectification?"

The Master said, "How uncultivated you are, Yu! The superior man cannot care

about the everything, just as he cannot go to check all himself!

If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of

things.

If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot

be carried on to success.

When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music do

not flourish.

When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be

properly awarded.

When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know

how to move hand or foot.

Therefore if the superior have got everything the a propriate name,he would

find it convient to give orders.If he give orders ,it will be always appropriately

carried out.Then,he cannot blame you,because you can always appropicately.."

(Analects XIII, 3, tr. Legge)

Xun Zi chapter (22) "On the Rectification of Names" claims the ancient sage-

kings chose names (Chinese: []; pinyin: mng) that directly corresponded with

actualities (Chinese: []; pinyin: sh), but later generations confused

terminology, coined new nomenclature, and thus could no longer distinguish right

from wrong.

Submitted to:

Mr. Alvin Charles Lopez

Submitted by:

Erika Arboleras

Rashea Ghazi

Farrah Jade Lumenda

Norhata Calimbol

Bai Sandra Sinagandal

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Doyle Rizzo Daniela Darlene - TP Source AnalysisDokumen3 halamanDoyle Rizzo Daniela Darlene - TP Source AnalysisDaniela DoyleBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Geno GramDokumen4 halamanGeno GramErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- NPC Vs CoDokumen5 halamanNPC Vs CoErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- CVA NCPDokumen6 halamanCVA NCPErika Arboleras0% (1)

- Different Breed of DogsDokumen601 halamanDifferent Breed of DogsErika Arboleras25% (4)

- Symptoms of Diabetes MellitusDokumen72 halamanSymptoms of Diabetes MellitusErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- In For Ma TicsDokumen65 halamanIn For Ma TicsErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- ApolDokumen2 halamanApolErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- AmniocentesisDokumen46 halamanAmniocentesisErika ArbolerasBelum ada peringkat

- Golden-Turk EmpireDokumen40 halamanGolden-Turk EmpireAnelya NauryzbayevaBelum ada peringkat

- Baby Lock Unity BLTY Quick Reference Sewing Machine Instruction ManualDokumen64 halamanBaby Lock Unity BLTY Quick Reference Sewing Machine Instruction ManualiliiexpugnansBelum ada peringkat

- Culture - New World EncyclopediaDokumen8 halamanCulture - New World EncyclopediaYasir AslamBelum ada peringkat

- Ming-Yan Lai - Nativism and Modernity - Cultural Contestations in China and Taiwan Under Global Capitalism (S U N Y Series, Explorations in Postcolonial Studies) (2008) 2 PDFDokumen244 halamanMing-Yan Lai - Nativism and Modernity - Cultural Contestations in China and Taiwan Under Global Capitalism (S U N Y Series, Explorations in Postcolonial Studies) (2008) 2 PDFJayBelum ada peringkat

- Jpstate 9 - 19 LectureDokumen5 halamanJpstate 9 - 19 LectureRalf SingsonBelum ada peringkat

- Chapter 9 East Asian Connections, 300-1300: Notes, Part IDokumen17 halamanChapter 9 East Asian Connections, 300-1300: Notes, Part IDuezAP100% (1)

- A Brief History of The Chinese Martial Arts and ItDokumen5 halamanA Brief History of The Chinese Martial Arts and ItCarvalhoBelum ada peringkat

- How Many Provinces, Municipalities, Autonomous Regions, and Special Administrative Regions IN ALL Comprise Mainland China?Dokumen26 halamanHow Many Provinces, Municipalities, Autonomous Regions, and Special Administrative Regions IN ALL Comprise Mainland China?Steven Vinjean RotubioBelum ada peringkat

- Guide To Reading Chinese Characters (Symbols) On Charms: Chinese Charm Inscriptions (Partial List)Dokumen1 halamanGuide To Reading Chinese Characters (Symbols) On Charms: Chinese Charm Inscriptions (Partial List)WertholdBelum ada peringkat

- EssayDokumen3 halamanEssayAMARTYA CHOUBEYBelum ada peringkat

- The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) : 1. The Transition From Ming To Qing (Ming-Qing Transition)Dokumen4 halamanThe Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) : 1. The Transition From Ming To Qing (Ming-Qing Transition)N QuynhBelum ada peringkat

- GEACPSDokumen12 halamanGEACPSAnn Louise De LeonBelum ada peringkat

- Marele Zid Chinezesc 2021Dokumen1 halamanMarele Zid Chinezesc 2021Frasie SergiuBelum ada peringkat

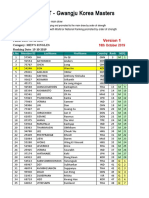

- Gwangju Korea Masters 2019 - M Q Report Version 1 - Updated Friday, 18th October 2019Dokumen17 halamanGwangju Korea Masters 2019 - M Q Report Version 1 - Updated Friday, 18th October 2019Yoga ParipurnaBelum ada peringkat

- What Is Comparative PoliticsDokumen33 halamanWhat Is Comparative PoliticsCrissanta MarceloBelum ada peringkat

- The AnalectsDokumen2 halamanThe AnalectsChristian EaBelum ada peringkat

- Introduction To Maldives As A DestinationDokumen15 halamanIntroduction To Maldives As A DestinationAnonymous sxsYbB0NUBelum ada peringkat

- Click Here: Mandarin Vocabulary - ShopsDokumen1 halamanClick Here: Mandarin Vocabulary - ShopsTortelliniTimBelum ada peringkat

- 1er Ranking Nacional Kiorugui 2023 Cadete y Junior LlavesDokumen37 halaman1er Ranking Nacional Kiorugui 2023 Cadete y Junior LlavesSissCupBelum ada peringkat

- Terracotta Army Cultural SignificanceDokumen5 halamanTerracotta Army Cultural Significanceggwp21Belum ada peringkat

- Chinese ArchitectureDokumen8 halamanChinese ArchitectureMj JimenezBelum ada peringkat

- Clinical Trials in Korea - Why KoreaDokumen9 halamanClinical Trials in Korea - Why KoreaTony LowBelum ada peringkat

- Region I La Union Schools Division OfficeDokumen15 halamanRegion I La Union Schools Division OfficeDawn Irad MillaresBelum ada peringkat

- (Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Pala (B-Ok - CC)Dokumen616 halaman(Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Anne Walthall, James Pala (B-Ok - CC)Jaqueline Briceño Montes100% (4)

- B.A. (Hons.) History History of China and Japan-I (1840-1949) SEM-V (7182) PDFDokumen3 halamanB.A. (Hons.) History History of China and Japan-I (1840-1949) SEM-V (7182) PDFGunjan0% (1)

- Japan PracticeDokumen58 halamanJapan PracticeawaisBelum ada peringkat

- Qing (Or Manchu) Dynasty Republic China: Chinese Revolution, (1911Dokumen1 halamanQing (Or Manchu) Dynasty Republic China: Chinese Revolution, (1911rudraarjunBelum ada peringkat

- The Body in Postwar Japanese Fi - Douglas N.Slaymaker PDFDokumen216 halamanThe Body in Postwar Japanese Fi - Douglas N.Slaymaker PDFSeb MihBelum ada peringkat

- Ancient China: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDokumen23 halamanAncient China: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StylebbalashBelum ada peringkat