Inequality, Piketty and India

Diunggah oleh

Ashish MehtaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Inequality, Piketty and India

Diunggah oleh

Ashish MehtaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

34 GovernanceNow | April 1-15, 2014

W

hy do we vote? We dont beneft from cast-

ing our votes; we dont beneft from not

casting our votes either, said Dinesh Nay-

ak, summing up the status of voter empow-

erment after more than six decades of de-

mocracy in India. Sitting on a plastic chair outside his hut

in Achhala village, he was talking about the plight of his

community, Nayaks or Naykas.

This village is close to Chhota Udepur, some 90 km from

Vadodara and a veritable headquarters of tribals in Gujarat.

The Rathwa community among adivasis are economically

somewhat better of even if life is difcult for many of them.

Rathwas have land and are not doing badly in agriculture,

cultivating maize. When the highway to Madhya Pradesh

passes through towns, one can notice signboards of doctors

with the Rathwa surname. A few Rathwas have made po-

litical careers from the reserved constituency (one was a

minister of state for railways in UPA I). But the Naykas are

a minority, indeed the marginalised among those who are

not far from the margins. Socially, they are one scale below

the Rathwas, many of whom till recently would not drink

water in a Nayka home.

Loktak Lake, near Moirang in Manipur, is

the largest freshwater lake in India.

Less equal

than others

Economic models have been vociferously debated this poll season, but there is little

discussion on the dening challenge of our time: economic inequality. It is increasing

fast, and Indias own 1% problem is bound to raise its head soon

Ashish Mehta

35 www.GovernanceNow.com

people politics policy performance

On Equality

Lallubhai Rathwa, who has studied

the Nayka community while working

from the Adivasi Academy of Tejgagh,

said the Naykas do not have land of

their own, and earn their living as

farm labourers, mostly in other parts

of Gujarat. This forced migration for

the better part of the year means they

cannot access quality health care and

their children cannot regularly attend

the local school for long.

What a welfare state can do for them

is to give them land, and that is very

much on the cards. Under the Forest

Rights Act (FRA), they can claim land

their forefathers used to till, but most

do not have proofs. Dinesh Nayak re-

called that the state government prom-

ised to distribute its unused land to the

poor and even distributed token certif-

icates of land rights at a garib kalyan

mela, or the poor welfare fair, in 2009,

but no one had got any land till the

2012 assembly elections, thanks to the

bureaucratic hurdles.

What the community has got from

our welfare state is job assurance un-

der MGNREGS (which they dont need),

money to construct houses under In-

dira or Sardar Awas Yojna (which has

certainly helped), a school and a health

centre (which they cannot use except

for a couple of months a year). What

the community has so far got from the

great white hope of our times, liberali-

sation and economic reforms, is better

and better wages that, however, are

not enough to keep up with the infa-

tion and certainly not enough to accu-

mulate capital.

The Dening Challenge of Our Time

When we debate growth versus devel-

opment, when we talk about the neo

middle class, when we list out benefts

of liberalisation, it would probably

help to keep in mind Dinesh Nayaks

friends, like the handicapped Luliyo

and a youngster too afraid to give his

name to a reporter.

They have certainly benefted from

economic reforms many of them

sport mobile phones and take joy rides

on motorcycles. They have jobs, even

if in the informal sector, and their in-

come has grown to an extent from

1991 to today. What they do not have

is capital: no land, no investment, no

higher-level skills. In other words,

a 44-year-old Nayak has seen his in-

come rising from 1991 to 2014 even if

it is not comparable to the rise enjoyed

by a 44-year-old Delhi-based journal-

ist. But the frst has no means to reap

benefts of an India emerging as one of

the fastest growing economies, where-

as the second has, and it shows not so

much in the income but in the capital

or wealth accumulated by the latter.

Also, unlike the former, the latter has

inherited some capital (a house, some

stocks).

If we compare the marginalised citi-

zen not with the middle-class taxpayer

but with a specimen of the top 1 per-

cent moneymakers in the country,

the contrast would be way too stark

again, not just in terms of income, but

also in terms of capital (especially the

inherited one), and the ability to reap

benefts of a global economy.

With this much background, here

is what we need to seriously come to

terms with: this contrast, this inequal-

ity is increasing. This is what US presi-

dent Barack Obama has called the de-

fning challenge of our time.

Dinesh Nayak of the tribal community of Naykas: will they ever be economically equal to the rest?

Whenever one speaks about the

distribution of wealth, politics is never very

far behind, and it is difcult for anyone to escape

contemporary class prejudices and interests.

Thomas Piketty

GN PHOTOS

36 GovernanceNow | April 1-15, 2014

Plenty of rationale for taxing richer people more

Do Pikettys diagnosis of

increasing inequality and

the prescription of fght-

ing it with more taxes

apply to India? We turned

to leading development

economist Reetika Khera.

She responded in an email

interview:

On using taxation to

reduce income inequality

There is immense unrealised potential

for revenue collection in India. Raising

tax rates as Piketty suggests, especially

raising the top marginal tax rate (from

the current 30% to, say, even 35%), is

a measure I would support (more on

that below).

More importantly, the tax base in

India continues to be very narrow.

According to the fnance ministers

budget speech, only about 3% of the

population pays taxes. Compare this

with a country such as the US which

is supposed to have a pro-rich taxa-

tion policy. There it is reported that

just over 50% pay income taxes, but

even that is considered low. Even

China has done much better than us:

in about 20 years, the proportion pay-

ing income tax increased from 0.1% to

20% in 2008!

Another reason for the

low tax base in India is tax

exemptions. For instance,

agricultural incomes re-

main tax-free even for the

20% farmers who are not

small or marginal. What

stops the state govern-

ments from levying a fat

10% on medium or large

farmers? According to the

budget documents, revenue foregone

due to various exemptions was more

than `5 lakh crore in 2013-14. That is

about 80% of our total revenue collec-

tion! Further, these exemptions tend

to be regressive: e.g., the diamond and

gold industry is among the highest

benefciaries of exemptions/rebates in

custom duties over `65,000 crores.

Coming back to the top marginal tax

rate, the rhetoric of the aam aadmi in

India is such that people who are at the

top of the income distribution in India

perceive themselves to be the middle

class, and feel sorry for themselves.

According to the ILO, the middle class

(though difcult to defne) includes

those whose incomes are between $4-

13 per day. Combined with the fact that

many subsidies (e.g., fuel) are enjoyed

by the better-of in India, there is plen-

ty of rationale for taxing richer people

more.

The top marginal tax rate in Den-

mark was at 60% in 2013. The US with

its pro-rich taxation policy set its top

rate at 40%. In India, it is only 30%.

Certainly we can do better. In order

to keep top marginal tax rates low,

many argue that the improvement in

income tax collections are due to the

reduction in marginal tax rates. Cer-

tainly that contributed, but the other

factor which contributed at least as

much, viz., tax deduction at source

(TDS), is never highlighted. The rich

(or aam aadmi) have too much

voice in the business media, in poli-

tics, and elsewhere too in the Indian

system.

On the nexus between economic and

social inequalities

The problems of economic and social

inequality are deeply connected in

India. It is not easy for us to fully ap-

preciate how social inequalities can af-

fect economic outcomes. Consider, for

instance, something as innocent as

rural habitation patterns, where Dalit

bastis are physically separate from

those of other communities. Often, be-

cause sanctions are sought and given

by non-Dalits, the most basic ameni-

ties such as hand-pumps, roads and

Growing inequality is a shocking sur-

prise, because growth is supposed to

take care of it. That has been the as-

sumption following from the work

of the American economist Simon

Kuznets, which is the standard text-

book view expressed in our policymak-

ing circles as the trickle-down theory:

if the economy grows, everybody ben-

efts even if some beneft less than

others. A rising tide, in the words of

John F Kennedy, will lift all boats. In-

stead, what is happening is what many

vaguely, simplistically put as this: the

rich have become richer and the poor

poorer.

More than growth, more than job

creation, economic inequality is the

biggest challenge before Indian econ-

omy in the 21st century. This conclu-

sion comes not from radicals but from

pro-market institutions like the Inter-

national Monetary Fund, Organisation

for Economic Cooperationa and Devel-

opment and Asian Development Bank.

In their majestic work last year, Un-

certain Glory: India and Its Contradic-

tions, Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen

were talking precisely about people

like the Naykas when they wrote:

Since Indias recent record of fast

economic growth is often celebrated,

with good reason, it is extremely im-

portant to point to the fact that the so-

cietal reach of economic progress in In-

dia has been remarkably limited.

While inequality is common around

the world, India has a unique cocktail

of lethal divisions and disparities of

caste, class and gender apart from the

economic ones with each adding to

the other.

The economist duo also underlined

the trend of growing economic inequal-

ity. Even if inequality had remained

static, poor people would have gained

much more from Indias rapid growth,

but the gap has increased, pushing the

poor down.

The ADB has specifc fgures too. A

February 2014 working paper calcu-

lates that the inequality (measured in

something called Gini coefcient: 0

means perfect equality, and 1 perfect

inequality) increased from 0.33 to 0.37

between the early 1990s and the late

2000s. The bottom-line: Had inequal-

ity not increased, the poverty head-

count rate at the $1.25-a-day poverty

line would have been 29.5% instead of

the actual 32.7% in 2010 in India.

If the Congress is voted out of power,

this would be a critical factor.

37 www.GovernanceNow.com

The Occupy movement

IN the west, the gap between the rich

and the poor has been a matter of hot

and excited debate for a while. First,

it was the Occupy movement of 2011

which drew attention to the 1 per-

cent (this slogan came from an essay

by Joseph Stiglitz, who noted that the

top one percent Americans had come

to control 40 percent of the countrys

wealth). And second, because a French

economist and his colleagues have put

together astounding data going back to

the 18th century and covering 20 coun-

tries, coming to the same conclusion in

a best-selling book.

Thomas Pikettys Capital in the

Twenty-First Century (translated from

French and published this month by

Belknap Press of Harvard University

Press) is attracting rave reviews. Paul

Krugman calls it a truly superb book.

Its a work that melds grand histori-

cal sweepwhen was the last time

you heard an economist invoke Jane

Austen and Balzac?with painstaking

data analysis This is a book that will

change both the way we think about

society and the way we do economics.

The Financial Times fnds it is an ex-

traordinarily important book. The ti-

tle and the ambition of the book have

invited comparisons with Marxs mag-

num opus, though the author modestly

points out diferences.

Pikettys central fnding is that the

level of inequality not just in incomes

but in overall capital, including wealth

(land, shares, etc) between the top

and bottom tiers of society in the west

was very high, but the shocks of the

two world wars and the states socialist

interventions later reduced the difer-

ence to an extent. However, since the

1990s inequality is increasing around

the world. He also briefy touches upon

the Indian case, based on income tax

data from 1922 to the early 2000s. His

prognosis: inequality in overall capital

is increasing. This is leading the world

back to the pre-1915 days, when the

rich were rich for generations and the

poor had no chance of making it big, no

matter what we are, in other words,

returning to patrimonial capitalism of

the kind portrayed in nineteenth cen-

tury novels.

In the case of India, it is possible to es-

timate (using tax return data) that the

increase in the upper centiles share of

national income explains between one-

quarter and one-third of the black

hole of growth between 1990 and

2000.

Piketty has explored the Indian scene

in detail in a discussion paper, written

with Abhijeet Banerjee (of Poor Eco-

nomics fame) and published by the

Centre for Economic Policy Research in

2004. Here are the specifc fndings of

Top Indian Incomes, 1922-2000:

Our data shows that the shares of the

top 0.01%, the top 0.1% and the top 1%

in total income shrank substantially

from the 1950s until the early-to-mid

1980s but then went back up again, so

that today these shares are only slight-

ly below what they were in the 1920s-

1930s. We argue that this U-shaped

pattern is broadly consistent with the

evolution of economic policy in India:

electricity come to non-Dalit bastis

frst. How does this afect econom-

ic outcomes? Take the example of

public transport, which would stop

where the road stops. Combined

with the fact that in some areas,

Dalits are still not allowed to enter

non-Dalit settlements, their access

to public transport may be entirely

cut of. Further, in some areas, they

may not even be allowed in the pri-

vate shared tempos. Thus, some-

thing as simple as commuting (say,

to a city for work) turns into a hur-

dle track for a Dalit person.

The same holds for discrimination

faced by women cultural norms

may inhibit (or prohibit even) wom-

ens economic opportunities. Re-

search by Thorat and Attewell in In-

dia suggests that call-back rates for

job interviews were systematically

lower for Muslim sounding names

compared with upper-caste Hindu

sounding names, even though the

CVs were exactly the same. Unfor-

tunately, there is great resistance in

India to accepting the existence of

such social inequalities, and their

repercussions on economic out-

comes and inequality. Inequality

economic or social appears to

have been completely internalised,

to the extent that they are not even

recognised as inequalities.

The rich-poor gap in India

Inequality in earnings has doubled in

India over the last two decades, making

it the worst performer on this count of all

emerging economies. The top 10 percent

of Indias wage earners now make 12 times

more than the bottom 10 percent, up from

a ratio of six in the early 1990s.

OECD report

people politics policy performance

On Equality

38 GovernanceNow | April 1-15, 2014

s

In particular, we do nd evidence of a substantial decline in

the share of the elite during the years of socialist planning

and a comparable recovery in the post-liberalization era.

However the rebound seems to start signicantly before the

ofcial move towards liberalization.

s

Our results suggest that the gradual liberalization of the

Indian economy did make it possible for the rich (the top 1%)

to substantially increase their share of total income. However,

while in the 1980s the gains were shared by everyone in

the top percentile, in the 1990s it was only those in the top

0.1% who big gains. The 1990s was also the period when the

economy was opened. This suggests the possibility that the

ultra-rich were able to corner most of the income gains in the

1990s because they alone were in a position to sell what the

world markets wanted.

Abhijeet Banerjee and Thomas Piketty, from discussion paper Top

Indian Incomes, 1922-2000

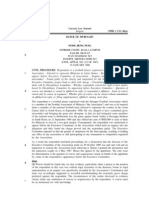

Year Top 1%

average income

Top 1%

income share

Top 0.01%

average income

Top 0.01%

income share

1922 122909.9 12.72 1936560 2

1924 126488.7 11.46 2026708 1.84

1926 128806.7 12.89 1868081 1.87

1928 138579.7 13.62 2009664 1.98

1930 140360.9 14.53 2037199 2.11

1932 157712.4 16.14 2271200 2.32

1934 167082.2 16.9 2387050 2.41

1936 151630.9 15.58 2252387 2.31

1938 173215.3 17.82 2814694 2.9

1940 173426.5 16.15 3204867 2.98

1943 96004.29 10.32 1738684 1.87

1945 104408.2 11.41 1858192 2.03

1947 112743.7 11.23 2279373 2.27

1949 107421.5 12 1875089 2.1

1953 113292.2 11.92 1756642 1.85

1955 148676.9 14.41 2079083 2.01

1957 136401.6 13.34 1720548 1.68

1959 136596.5 12.36 1594948 1.44

1961 145568.6 12.15 1647440 1.38

1964 128134.6 9.65 1385308 1.04

1966 123420.3 9.99 1436632 1.16

1968 125338.6 9.95 1270021 1.01

1970 133250.3 10.02 1364580 1.03

1971 113206.1 8.47 1176400 0.88

1973 97335.63 7.02 885240.5 0.64

1974 82113.85 6.65 667965.7 0.54

1975 87072.96 7.24 750223.8 0.62

1976 99674.22 7.27 844032.3 0.62

1977 87730.4 6.18 730013.8 0.51

1978 87660.84 6.05 744088.4 0.51

1979 80880.71 5.61 659410.3 0.46

1980 72505.42 4.78 599435 0.4

1981 67188.12 4.39 465055.4 0.3

1982 68884.89 4.51 524714.4 0.34

1983 101455 6.46 748364.2 0.48

1984 100723.7 6.39 785803.5 0.5

1985 134205.5 8.24 1076154 0.66

1986 140409.1 8.64 1133425 0.7

1987 134502.3 8.12 1048166 0.63

1988 150884 8.52 1467390 0.83

1989 154480.6 8.19 1463549 0.78

1990 147359.7 7.42 1261498 0.64

1991 139481.2 7.12 1114667 0.57

1992 136488.3 6.96 1160748 0.59

1993 179917.2 8.53 2428050 1.15

1994 180766.9 8.09 2388467 1.07

1995 199685.5 8.67 4716301 2.05

1996 207252.8 8.72 3655103 1.54

1997 262105.7 10.7 4603855 1.88

1998 223561.1 8.95 3926823 1.57

1999 229679.3 8.95 4034289 1.57

An unequal music

Not even top 1%, its top 0.01% India that benefts

Source: Banerjee, Abhijit and Piketty, Thomas (2010). Top Indian Incomes 1922-2000; in Atkinson, A B and Piketty, T (eds) Top Incomes: A Global Perspective, OUP.

Data and graphs via: Alvaredo, Facundo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, The World Top Incomes Database, http://topincomes.g-mond.

parisschoolofeconomics.eu/, 23/04/2014

39 www.GovernanceNow.com

The period from the 1950s to the ear-

ly-to-mid-1980s was also the period of

socialist policies in India, while the

subsequent period, starting with the

rise of Rajiv Gandhi, saw a gradual

shift towards more pro-business poli-

cies. Although the initial share of this

group was small, the fact that the rich

were getting richer had a non-trivial

impact on the overall income distri-

bution. In particular, its impact is not

large enough to fully explain the gap

observed during the 1990s between

average consumption growth in sur-

vey-based NSS data and the National

accounts based NAS data, but is suf-

ciently large to explain a non-negligi-

ble part of it (between 20% and 40%).

Crony capitalism of the past decade

must have pushed this trend fur-

ther, and the next government will be

cheered heavily to pursue even more

pro-business policies. In short, inequal-

ity is going to only increase further.

The Costs and Benets of Inequality

Disparities between the rich and the

poor can be shrugged of as a fact of

life: the world has indeed never seen

an ideal society where everybody was

equal. Indeed, economists even speak

of benefts of inequality. For example,

it can motivate innovation, dynamism,

and entrepreneurship if it is within

limits and not galloping away, which is

the case now.

As for the harms of inequality if they

need to be listed out there are many.

Dreze and Sen say inequality leads to:

n

Hurdles poverty reduction eforts

n

Worsening health scenario for the

whole of society,

n

More crimes,

n

Less social solidarity and civic coop-

eration, and

n

Disproportionate political power to

a privileged minority, reinforcing

elitist biases in public policy.

As Piketty told the New York Times,

its very difcult to make a democratic

system work when you have such ex-

treme inequality in income and in

political infuence. (No wonder, the

Naykas have often contemplated boy-

cotting elections.)

And, of course, all of these eventually

impact economic growth itself. So, in-

equality needs to be addressed even

for the sake of higher growth in future.

Pikettys Prescriptions

Piketty has a range of policy prescrip-

tions, too, and at the time of writing

many in the US including the treasury

secretary were queuing up to hear

the same from him. Pikettys panacea

is: a progressive global tax on wealth

over 1 million euros. Not likely, but let

us at least note that it is not likely due

to political reasons. This proposal has

predictably attracted ferce criticism

from the pro-market press, but Piket-

ty sees taxation as the most powerful

weapon in this fght. In Indian terms,

this should mean high wealth and in-

heritance tax for the top 1 percent, or

even 0.01 percent level. (By the way,

the fedgling middle class need not

worry: he in fact recommends doing

away with property tax for the lower

half or even lower three-fourths of

property tax payers.)

The next on the to-do list is something

very much in demand for our own ver-

sions of Occupy agitators: force tax

havens to release the wealth hoarded

there. Its a question of political will.

He told the New York Times, If we can

send one million troops to Kuwait in a

few months to return the oil, presum-

ably we can do something about tax

havens using trade sanctions.

Efective redistribution of land, a ma-

jor asset, can help. Higher education

helps one go up the economic hierar-

chy. Access to capital can help the poor.

A range of specifc prescriptions can

be considered, once we come to terms

with the fact that the increasing gap

between the rich and the poor is not

some god-given law for which little can

be done: fnally it is a political choice,

and its the political policy that has

consciously or otherwise taken us to

where we are today.

Piketty puts it better: Whenever

one speaks about the distribution of

wealth, politics is never very far be-

hind, and it is difcult for anyone to

escape contemporary class prejudices

and interests. n

ashishm@governancenow.com

85 people = half the world!

Christine Lagarde

Director, IMF

Seven out of ten people

in the world today live in

countries where inequality

has increased over the past

three decades. [India is one of them.]

Some of the numbers are stunning

according to Oxfam, the richest 85

people in the world own the same

amount of wealth as the bottom half of

the worlds population.

With facts like these, it is not surprising

that inequality is increasingly on the

global communitys radar screen. It is

not surprising that everyone from the

Confederation of British Industry to

Pope Francis is speaking out about it

because it can tear the precious fabric

that holds our society together.

Let me be frank: in the past, economists

have underestimated the importance

of inequality. They have focused on

economic growth, on the size of the pie

rather than its distribution. Today, we are

more keenly aware of the damage done

by inequality. Put simply, a severely

skewed income distribution harms the

pace and sustainability of growth over

the longer term. It leads to an economy

of exclusion, and a wasteland of

discarded potential.

Excerpted from a February 2014 speech

people politics policy performance

On Equality

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- Te V BrevaDokumen2 halamanTe V Brevaevealyn.gloria.wat20Belum ada peringkat

- Dir of Lands v. IAC and EspartinezDokumen3 halamanDir of Lands v. IAC and EspartinezKerriganJamesRoiMaulitBelum ada peringkat

- Stages of Civil Trial in PakistanDokumen4 halamanStages of Civil Trial in PakistanAbdulHameed50% (4)

- Alfred McCoy Political Caricatures of The American EraDokumen33 halamanAlfred McCoy Political Caricatures of The American EraSerg's Bihag IVBelum ada peringkat

- Anglais: Secret Séries: L1b-L2-LA - Coef. 2Dokumen4 halamanAnglais: Secret Séries: L1b-L2-LA - Coef. 2secka10Belum ada peringkat

- Loomba, A. (1998) Situating Colonial and Postcolonial Studies and Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (1986) Decolonising The Mind'Dokumen2 halamanLoomba, A. (1998) Situating Colonial and Postcolonial Studies and Ngugi Wa Thiong'o (1986) Decolonising The Mind'Lau Alberti100% (2)

- SBMA V ComelecDokumen13 halamanSBMA V ComelecNatalia ArmadaBelum ada peringkat

- NASDokumen9 halamanNASNasiru029Belum ada peringkat

- Logic Id System DebateDokumen6 halamanLogic Id System DebatesakuraBelum ada peringkat

- G.R. No. 161921 July 17, 2013 Joyce V. Ardiente, Petitioner, Spouses Javier and Ma. Theresa Pastorfide, Cagayan de Oro Water District and Gaspar Gonzalez, JR., RespondentsDokumen4 halamanG.R. No. 161921 July 17, 2013 Joyce V. Ardiente, Petitioner, Spouses Javier and Ma. Theresa Pastorfide, Cagayan de Oro Water District and Gaspar Gonzalez, JR., RespondentsKhayzee AsesorBelum ada peringkat

- Blokland - Pluralism, Democracy and PoliticalDokumen560 halamanBlokland - Pluralism, Democracy and PoliticalFernando SilvaBelum ada peringkat

- CASE OF RADU v. THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVADokumen12 halamanCASE OF RADU v. THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVAneritanBelum ada peringkat

- Law On Local Administration (2003) EngDokumen24 halamanLaw On Local Administration (2003) Engkhounmixay somphanthamitBelum ada peringkat

- Corporal Punishment Versus Capital PunishmentDokumen8 halamanCorporal Punishment Versus Capital PunishmentWac GunarathnaBelum ada peringkat

- United Paracale Vs Dela RosaDokumen7 halamanUnited Paracale Vs Dela RosaVikki AmorioBelum ada peringkat

- Wong Hung NungDokumen4 halamanWong Hung NungMiaMNorBelum ada peringkat

- Bar Questions 2011 With AnswersDokumen11 halamanBar Questions 2011 With AnswersSonny MorilloBelum ada peringkat

- Implementing Rules and Regulations Governing Summary Eviction Based From Ra 7279 & Oca No. 118-2013Dokumen4 halamanImplementing Rules and Regulations Governing Summary Eviction Based From Ra 7279 & Oca No. 118-2013Truman TemperanteBelum ada peringkat

- A Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic PeasantDokumen12 halamanA Return To The Figure of The Free Nordic Peasantcaiofelipe100% (1)

- Tsasec 1Dokumen2 halamanTsasec 1The Daily HazeBelum ada peringkat

- Instructions To Bidders: These: Provisions Refer To Pre-Construction Activities From Advertisement To Contract AwardDokumen5 halamanInstructions To Bidders: These: Provisions Refer To Pre-Construction Activities From Advertisement To Contract Awardketh patrickBelum ada peringkat

- The Budget ProcessDokumen16 halamanThe Budget ProcessBesha SoriganoBelum ada peringkat

- Sofia Petrovna EssayDokumen4 halamanSofia Petrovna EssayMatthew Klammer100% (1)

- Assignment: "The Practice of ADR in Bangladesh: Challenges and OpportunitiesDokumen23 halamanAssignment: "The Practice of ADR in Bangladesh: Challenges and OpportunitiesNur Alam BappyBelum ada peringkat

- People V Del RosarioDokumen2 halamanPeople V Del RosariocaloytalaveraBelum ada peringkat

- Motion For Pitchness (AutoRecovered)Dokumen5 halamanMotion For Pitchness (AutoRecovered)NICK HUFF100% (1)

- Law of Immovable Property Tutorial (Reworked)Dokumen5 halamanLaw of Immovable Property Tutorial (Reworked)Bernard Nii AmaaBelum ada peringkat

- Consumer Protection Act (Amended) 2002Dokumen21 halamanConsumer Protection Act (Amended) 2002Rahul MishraBelum ada peringkat

- Andhra Pradesh State Administration Reprot 1969-70 - HK - CSL - IO050651Dokumen458 halamanAndhra Pradesh State Administration Reprot 1969-70 - HK - CSL - IO050651CHALLA MOUNICABelum ada peringkat

- Tughlaq As A Political AllegoryDokumen2 halamanTughlaq As A Political AllegoryAmritaBanerjee86% (7)