78 Full

Diunggah oleh

bubickaJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

78 Full

Diunggah oleh

bubickaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) Reconsidered: Validation and

Reference Values From Different Clinical and Healthy Adult Samples

HERBERT FLIEGE, PHD, MATTHIAS ROSE, MD, PETRA ARCK, MD, OTTO B. WALTER, MD,

RUEYA-DANIELA KOCALEVENT, MA, CORA WEBER, MD, AND BURGHARD F. KLAPP, MD, PHD

Objective: The aim was to translate, revise, and standardize the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) by Levenstein et al. (1993) in

German. The instrument assesses subjectively experienced stress independent of a specific and objective occasion. Methods: Exploratory

factor analyses and a revision of the scale content were carried out on a sample of 650 subjects (Psychosomatic Medicine patients, women

after delivery, women after miscarriage, and students). Confirmatory analyses and examination of structural stability across subgroups

were carried out on a second sample of 1,808 subjects (psychosomatic, tinnitus, inflammatory bowel disease patients, pregnant women,

healthy adults) using linear structural equation modeling and multisample analyses. External validation included immunological measures

in women who had suffered a miscarriage. Results: Four factors (worries, tension, joy, demands) emerged, with 5 items each, as

compared with the 30 items of the original PSQ. The factor structure was confirmed on the second sample. Multisample analyses yielded

a fair structural stability across groups. Reliability values were satisfactory. Findings suggest that three scales represent internal stress

reactions, whereas the scale demands relates to perceived external stressors. Significant and meaningful differences between groups

indicate differential validity. A higher degree of certain immunological imbalances after miscarriage (presumably linked to pregnancy

loss) was found in those women who had a higher stress score. Sensitivity to change was demonstrated in two different treatment samples.

Conclusion: We propose the revised PSQ as a valid and economic tool for stress research. The overall score permits comparison with

results from earlier studies using the original instrument. Key words: stress perception, stress measurement, tinnitus, inflammatory bowel

diseases, pregnancy, immunology.

PSQ Perceived Stress Questionnaire; ICD International Clas-

sification of Diseases; QoL quality of life; IBD inflammatory

bowel disease; SEM structural equation modeling; MSA mul-

tisample analysis; TLI Tucker-Lewis index; CFI comparative

fit index.

INTRODUCTION

S

tress is a key concept in health research (1). Definitions

have basically focused on two major components of stress:

a) stressors in terms of environmental conditions, and b) the

persons reaction to stress. Stress reactions have been further

differentiated theoretically, for example, into perceptional

processing and emotional response. An empirical study based

on structural equation modeling techniques found that the

experience of stress was best represented by a two-factorial

construct of stress (2). Environmental conditions were one

factor; stress appraisal and emotional response in combination

comprised the second.

With regard to the measurement of stress, it has been much

debated whether or not we should limit ourselves to measuring

stressors in terms of objective conditions, such as major life

events or cumulative minor stressors (eg, daily hassles), or if

we should rather concentrate on the persons stress reactions,

in terms of their stress appraisal or emotional response (3).

Stress research has shown an inconsistent picture of the effects

of life events or daily hassles on health. Empirical studies have

shown many instances in which an experience of accumulated

or chronic stress led to physical health problems, whereas

more severe but acute and temporally more contained life

events could not predict illness to the same extent (46).

Obviously, the personal impact of life events cannot be deter-

mined before the event has actually occurred (7). Other ap-

proaches have shifted the focus from specific objective stres-

sors to more chronic and subjective stress experience (8).

Stress definitions have become more strongly focused on

the subjective reactions to external events or demands (9). In

the revised stress measure Hassles and Uplifts Scale (10),

for example, we see both an environmental and an appraisal

measure of stress, because it assesses not only whether a

hassle occurs but also the perception of its severity or inten-

sity. Nevertheless, many researchers have gone further and

called for the development of instruments for the assessment

of stress focused primarily on the subjective perception of the

individual (3,1113).

Against this background, Levenstein et al. (14) published

the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) 10 years ago. It

had been their aim to overcome some of the difficulties

concerning the definition and measurement of stress by put-

ting the focus on the individuals subjective perception and

emotional response. With this aim in mind, item wordings

were designed to represent the subjective perspective of the

individual (You feel. . . ). The presented stress experiences

were intended to be abstract enough to be applicable to adults

of any age, stage of life, sex, or occupation, but at the same

time interpretable as specific to a variety of real-life situations.

For example, you feel under pressure from deadlines could

refer to anything from a payment, to an oncoming birthday

party, or to a grant proposal. Factorial analyses resulted in 7

dimensions (harassment, irritability, lack of joy, fatigue, wor-

ries, tension, and overload). The authors made no a priori

distinction between presumed stressor and stress response

items. Although stress reactions certainly predominate the

content of the scales, the overload subscale (too many things

From the Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Charite-University Hos-

pital Berlin, Berlin, Germany.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Herbert Fliege,

Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Charite - University Hospital

Berlin, Luisenstrasse 13 a, D-10117 Berlin, Germany. E-mail: herbert.

fliege@charite.de

Received for publication December 1, 2003; revision received August 19,

2004.

Financial aid was granted by the Humboldt-University Medical Faculty

Research Fund (UFF-N. 99648/99652). The ethics committee approved

of the study design (N 209/98/107/99).

DOI: 10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78

78 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

0033-3174/05/6701-0078

Copyright 2005 by the American Psychosomatic Society

to do, too many decisions to make, etc) seemed at least to

reflect the perception of stressful environmental conditions.

Psychometric characteristics proved to be favorable. PSQ

scores correlated moderately with Cohens Perceived Stress

Scale (described later in this section), anxiety (State-Trait-

Anxiety Inventory), and depression (CES-D Depression

Scale). As far as external validity was concerned, PSQ values

were higher in asymptomatic ulcerative colitis patients with an

inflamed rectal mucosa than in those with a normal-appearing

rectum. By choosing only patients in clinical remission, con-

founds resulting from the distressing effects of symptoms

were eliminated. Furthermore, the authors were able to predict

adverse health outcomes by means of PSQ values in a pro-

spective study (15).

It seemed, therefore, that the instrument was properly qual-

ified for research on stress and illness. However, there were

certain flaws that suggested to us that reconsideration and

further development of the questionnaire should take place.

First, the original validation study relied on relatively small

samples. The overall sample comprised 230 subjects. Another

point of concern is the number of scales. Although the pattern

of item loadings could be satisfactorily interpreted, a total of

7 scales drawn from the original 36 items, tested on 230

subjects, seems fairly high from a statistical point of view. In

4 of the 7 scales, all item loadings scored below 0.50. This

might indicate that a 7-factor solution does not rely on a

sufficiently robust statistical basis. Finally, the clinical sam-

ples originally consisted only of patients with gastroenter-

ological diseases. In a Spanish study, the PSQ was adminis-

tered to psychiatric patients, nursing students, and healthy

adults (16). Another study yielded moderate overall PSQ

scores for a Swedish population sample (17). There was some

evidence for external validity in a Thai sample of patients with

peptic ulcer disease (18). In our opinion, the PSQs dimen-

sional structure should be investigated in different clinical

groups and further reference values should be established.

Because there are some alternative stress questionnaires

available that are also based on a concept of stress as a

subjective experience, we will briefly point out what distin-

guishes them from the PSQ.

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) (11) is probably the most

widely accepted of these measurements of stress. This 14-item

questionnaire asks the respondent how often certain experi-

ences of stress occurred in the last month. Stressas opposed

to challengeis believed to result from experienced overload

with further emphasis on experienced unpredictability and

uncontrollability of events. This implies that the existence of

stress in a person is partly inferred from information on the

persons experience of lack of control. The content of the

items is nonspecific. Two items directly address stress or

hassles, three refer to situations of overload, whereas nine

items refer to uncontrollable, unmanageable, or unpredictable

situations. Thus, the PSS focuses on a more cognitive ap-

praisal of stress and the respondents perceived control and

coping capability. A total score is provided. No subscales are

reported.

The Index of Clinical Stress (ICS) (19) consists of 25

items. These items are designed to indicate affective states

involved in the stress reaction. Cognitive appraisals, physical

signs, or behavioral reactions are not considered. The ICS

consists of one homogeneous scale. Subscales are not pro-

vided. The questionnaire lacks external validation.

The recently published Stress Response Inventory (SRI)

(20) consists of 39 items that comprehensively focus on cog-

nitive, emotional, behavioral, and somatic stress responses. In

addition to a total score, its subscales differentiate between

depression, frustration, anger, aggression, tension, and soma-

tization. It does not cover the individuals perception of ex-

ternal stressors or demands.

The Trier Inventory for the Assessment of Chronic Stress

(TICS) (21) is a validated German questionnaire focusing on

chronic stress. The 39 items are factor-analytically assigned to

6 scales: work overload, work discontent, social stress, lack of

social recognition, worries, and intrusive memories. The em-

phasis is on work-related and other socially stressful environ-

mental conditions. To our knowledge, no English version has

been published.

In comparison to the aforementioned instruments, we sug-

gest that the PSQ is most useful

1. when, from a conceptual point of view, perceived stress

should be asked as directly as possible, without inferring it

from control or coping appraisals;

2. when, in addition to an overall score, different facets of

perceived stress are of interest;

3. when information is wanted, not only concerning the

persons stress response, but also concerning the perception of

external stressors.

The first aim of our study was to investigate the dimen-

sional structure of the questionnaire on a larger sample drawn

from a different cultural context. Because questionnaires that

might be included in routine use should keep respondent

burden as small as possible, we aimed to reduce the length of

the PSQ. In the course of item reduction, the explanatory

power of different scales was to be balanced. Finally, we

wanted to provide normative values for different clinical

groups and healthy adults.

Concerning external validation, we expected that a higher

perceived stress level in women who had experienced a spon-

taneous abortion would be associated with a higher concen-

tration of certain immune parameters considered to be medi-

ating factors in triggering spontaneous abortions (22). With

regard to the instruments sensitivity, we expected higher

stress levels in women after miscarriage and inpatient groups,

especially those who were treated with somatoform and de-

pressive symptoms, and lower stress levels in pregnant women

and healthy adults.

METHODS

Study Design

We administered the original 30-item questionnaire to one sample of

participants (N 650) in order to explore the factorial structure and to reduce

the length of the questionnaire on one set of data. We then administered only

PERCEIVED STRESS QUESTIONNAIRE

79 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

the resulting item-reduced version of the questionnaire with 20 items to

another sample (N 1808) to test for structural stability on a completely

separate set of data.

Samples

The study included two samples that involved a total of 2,458 participants.

1. The first sample (N 650) is composed of the following:

246 patients hospitalized in the Psychosomatic Medicine ward, that is,

patients with mental or behavioral disorders associated with at least one

complex of somatic complaints or illness (included are somatoform,

affective, eating disorders, other neurotic disorders, and personality

disorders, all according to ICD-10 F3 to F6; excluded are organic,

addictive, or psychotic disorders according to ICD-10 F0 to F2) (77.6%

female, 22.4% male; age 38.9 15.4 years, range 1779),

81 female patients after miscarriages of unexplained origin (age 30.2

7.7, range 1741),

74 women after regular delivery (age 30.2 5.0, range 1943), and

249 medical students in the 4th year (51.1% female, 48.9% male; age

24.6 2.9, range 2041).

Initial results from this sample have been published in German (23).

2. The second sample (n 1808) is composed of the following:

559 Psychosomatic Medicine outpatients (diagnoses as above) (63.9%

female, 36.1% male; age 37.8 15.3, range 1872),

184 outpatients with tinnitus (46.6% female, 53.4% male; age 42.1

12.7, range 2870),

144 outpatients with inflammatory bowel diseases (54.7% female,

45.3% male; age 39.6 14.2, range 2267),

587 women in routine care at week 8 of pregnancy (age 29.6 5.3,

range 1744), and

334 healthy adults (61.6% female, 38.4% male; age 45.3 15.6, range

1888) who were visitors to a well-frequented institution for public

education. (We defined only those participants as healthy who de-

clared that they did not have any chronic or acute disease, were not in

constant medical treatment, and were not in permanent need of medi-

cation).

3. Sensitivity to change was tested in the following:

in 91 of the abovementioned sample of 246 Psychosomatic Medicine

inpatients who were treated 5 weeks or more, so that we could measure

at admission and after 5 weeks; treatment included a combination of

single and group psychotherapy, relaxation training, sports, and in

some cases antidepressants; and

in 46 tinnitus outpatients who were assessed before and after 10 weekly

sessions of progressive muscle relaxation training (27).

All patient groups were recruited in routine care. The students were

recruited at the end of a course. The healthy adults were recruited before or

at some time during the event that they visited. All participants were told

about the aims of the study and gave their informed consent to participate.

Instruments

Levenstein et al. (14) developed the PSQ to assess perceived stressful

situations and stress reactions on a mainly cognitive and to some degree

emotional level. With regard to stressors, the aim was to assess the subjective

experience of their quality as stressful.

The scale construction was based on classical test theory and was carried

out by factor analyses. The final instrument comprises 30 items that fell on

factor analysis into 7 scales (harassment, overload, irritability, lack of joy,

fatigue, worries, tension). Respondents rate how often an item applies to them

on a 4-point scale (1: almost never, 2: sometimes, 3: often, and 4: usually). The

general form of the instruction asks in general, in the last two years, the

recent form asks during the last month (both in (14)). The PSQ Index and

the scale values are mean values that are calculated from the raw item scores

and linearly transformed to values between 0 and 1. The instrument was

originally validated in English-speaking and Italian-speaking samples of

gastroenterological inpatients, outpatients, hospital employees, and students

(overall N 230).

We translated the questionnaire into German. A clinical psychologist and

English native speaker who had no prior knowledge of the instrument trans-

lated it back into English. Deviations from the original were examined, and

the German translation was optimized accordingly.

On the samples presented here, we applied the general form of the ques-

tionnaire. According to the authors, it integrates an individuals stress in the

long run, [and] may be a superior predictor of health status (Levenstein et al.,

1993, p. 30). To avoid problems resulting from varying or insufficient memory

recall, we omitted the time span of the last year or two. So the respondent was

only asked to rate how often an item applied in general.

For purposes of validation, we administered the short measure of quality of

life by the World Health Organization (WHOQOL-Bref (24)) and the abovemen-

tioned Trier Inventory of Chronic Stress (TICS (21)) to part of the sample.

The time needed to complete the questionnaire was recorded for the

sample of 559 Psychosomatic Medicine outpatients.

Statistical Procedures

Exploration

An exploratory principal component factor analysis of the 30-item ques-

tionnaire was performed on the data from the first sample using SPSS.

Because it could be expected that factors were correlated, an oblique rotation

(promax, power coefficient 4) was conducted. The factors were defined and

interpreted based on the factor pattern matrix. We also tested whether the

original 7-factor solution could be replicated on the German samples.

Item Reduction

The first rationale for item selection was to balance the explanatory power

between the scales by attaining scales of (approximately) equal length. The

second rationale was to maximize reliability of the resulting scales by selecting

those items that showed the highest corrected item-scale-correlation (Table 1).

Confirmation

We tested for structural stability on the data from the second sample,

where subjects were administered only those 20 items that had resulted from

the item selection. We tested a structure of 4 factors by means of linear

structural equation modeling (SEM, Program Amos

TM

4.0), allowing for one

latent stress construct to underlie all 4 factors (Figure 1). In addition, we tested

a 3-factorial and a 2-factorial structure, also allowing for correlations between

the factors. We tested the 4-factorial structure for dimensional stability across

groups by multisample analyses (MSA) using SEM. We performed several

different comparisons between ill and healthy samples, combined and sepa-

rate (Table 2). Because we expected mean values to differ across groups, we

added a mean structure to the MSA model. To examine whether the factors

can be defined the same way in all groups, cross-group equality constraints

were imposed on the factor loadings (one loading was fixed to 1 in all groups).

The mean of the factor was fixed to 0 in one group and estimated freely in the

other groups (one indicator intercept per factor was fixed to 1 in all groups).

Because this analysis did not aim to test hypotheses about means, no other

equality constraints across groups were imposed.

For purposes of the MSA, all factor loadings of the observed variables

(items) on latent traits (factors) and all loadings of the primary factors on the

superordinate factor (stress reaction) and the correlation between de-

mands and stress reaction were assumed to be constant across groups.

Validation

To corroborate construct validity, we performed comparisons with a

measure of quality of life (WHOQOL-Bref (24)) and with a questionnaire of

chronic stress (TICS (21)) that had been applied in two partial samples.

To determine criterion validity, we tested for associations between stress

scores and immunological parameters in women suffering from a spontaneous

abortion (22). We took decidual tissue biopsies and determined the occurrence of

CD56

-NK-cells, CD8

- and CD3

-T-cells, tryptase

-mast cells (TMC

) and

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

-cells (TNF-

) by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

All biopsies were fixed in 5% formalin and embedded in paraffin. We

H. FLIEGE et al.

80 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

examined two to four different sections of tissue for each patient. To make

sure the trophoblast had been in contact with maternal immunocompetent cells

and could have been a target of rejection, we stained the tissue with a monoclonal

antibody against pancytokeratin (CK) to test for invasive fetal cells. Consecutive

slides were stained with monoclonal antibody against mast cell tryptase, CD3,

CD8, or CD56, respectively. Probes for human TNF- mRNA were stored at

70C until use. Five-micron paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated,

washed in DEPC-treated water, and immersed in 0.1N HCl followed by 2SSC

at RT. Sections were exposed to 10 g/ml proteinase K and postfixed in 0.4%

paraformaldehyde at 4C. Hybridization was carried out at 59C using S

35

UTP-labeled cRNA. Afterward, sections were washed in 4 SSC and treated

with RNase A (20 l/ml). The slides were desalted, dehydrated, air dried, dipped

into autoradiography emulsion, and developed. The sections were counterstained

with hemalaun. Microscopic investigators were blinded to the patients stress

scores. The number of positive cells per square millimeter tissue was evaluated by

two independent observers.

To examine sensitivity, we tested patient samples, pregnant women, and

healthy adults for differences in their stress levels. All differences between

samples were investigated by analysis of variance and secured by post-hoc t tests.

RESULTS

Dimensional Structure

Exploration and Item Reduction

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of the quality of the

correlation matrix was high (KMO 0.96). A significant

Bartlett test of sphericity justified a dimension reducing pro-

cedure such as the factor analysis. The measure of sampling

adequacy was over 0.80, so the items could be considered apt

for factor analyses.

Exploratory analyses of all 30 items yielded a different

solution from the original one (14). A forced 7-factor solution

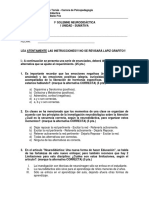

TABLE 1. Exploratory Factor Analysis With Promax-Rotation of the Original 30 PSQ Items From Sample 1 (n 650)

Items No.

Primary Components (all 30 items)

Item parameters

(20 selected items)

Loadings

h2 r

i(ti)

I II III IV M sd p

Factor I: 41.6% explained variance (rotated solution)scale

worries

x You are afraid for the future 22 .789 .028 .054 .200 .61 .69 2.08 1.01 .36

x You have many worries 18 .766 .100 .028 .061 .63 .73 2.23 0.98 .41

x Your problems seem to be piling up 15 .745 .136 .067 .083 .71 .77 2.10 0.96 .36

You feel lonely or isolated 05 .710 .073 .210 .231 .55 .63

x You fear you may not manage to attain

your goals

09 .700 .138 .004 .115 .57 .69 2.18 0.94 .39

You find yourself in situations of conflict 06 .697 .031 .081 .080 .51 .63

You are under pressure from other people 19 .689 .258 .124 .285 .59 .64

You feel discouraged 20 .670 .134 .190 .230 .67 .63

You feel criticized or judged 24 .620 .368 .287 .197 .50 .56

x You feel frustrated 12 .560 .213 .138 .077 .59 .69 1.97 0.89 .32

You feel youre doing things because you

have to not because you want to

23 .528 .185 .378 .139 .55 .64

You feel loaded down with responsibility 28 .505 .132 .058 .341 .59 .63

You have too many decisions to make 11 .453 .128 .259 .349 .45 .47

Factor II: 8.0% explained variancescale tension

You feel tired 08 .168 .758 .067 .117 .55 .58

x You feel tense 14 .211 .691 .139 .047 .63 .68 2.45 0.81 .48

x You feel rested 01 .231 .688 .309 .179 .66 .66 2.69 0.89 .56

x You feel mentally exhausted 26 .173 .589 .151 .012 .63 .68 2.18 0.88 .39

x You have trouble relaxing 27 .246 .543 .047 .002 .56 .66 2.28 1.00 .43

x You feel calm 10 .109 .501 .187 .150 .57 .67 2.64 0.99 .55

You are irritable or grouchy 03 .175 .232 .169 .109 .28 .46

Factor III: 5.0% explained variancescale joy

x You feel youre doing things you really like 07 .064 .003 .737 .069 .63 .61 2.31 0.89 .44

x You enjoy yourself 21 .201 .214 .597 .109 .70 .75 2.34 0.87 .45

x You are lighthearted 25 .082 .191 .552 .022 .52 .64 2.71 0.95 .57

x You are full of energy 13 .001 .391 .538 .181 .59 .60 2.63 0.90 .54

x You feel safe and protected 17 .400 .097 .410 .022 .58 .63 2.35 1.04 .45

Factor IV: 3.4% explained variancescale demands

x You have too many things to do 04 .185 .091 .042 .841 .66 .61 2.42 0.91 .47

x You have enough time for yourself 29 .330 .015 .380 .792 .65 .51 2.59 1.01 .53

x You feel under pressure from deadlines 30 .084 .130 .197 .692 .57 .59 2.17 0.93 .39

x You feel youre in a hurry 16 .357 .161 .052 .455 .58 .58 2.06 0.87 .35

x You feel that too many demands are being

made on you

02 .360 .072 .038 .447 .54 .58 2.17 0.79 .39

h

2

communality; M mean (before transformation); sd standard deviation; r

i(ti)

corrected item-scale correlation; p item difficulty.

Note: Remaining items are marked with an X.

PERCEIVED STRESS QUESTIONNAIRE

81 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

did not yield the original structure. Four factors were extracted

with eigenvalues greater than 1. The eigenvalues course was

12.5, 2.4, 1.5, and 1.0, then 0.9, 0.8, and 0.8, indicating a

strong primary factor with 1 to 3 additional factors. We tested

solutions with 4, 3 and 2 factors, respectively.

The 4-factor solution accounted for 58% of the variance.

Item 03 (You are irritable or grouchy) did not load distinctly

and item 11 (You have too many decisions to make) had a

low communality (0.50). They were therefore excluded.

Item 17 (you feel safe and protected) loaded on factor III

(0.410) but also on factor I (0.400). Still, we decided to

accept this flaw and keep the item with a view to keeping

scales of even length and in light of its satisfactory commu-

nality (0.58).

All remaining factor loadings were greater than 0.50 and

the items share of communality concerning one factor was at

least 20% higher than its share of communality concerning

any other factor. Communality varied between 0.50 and 0.71

around a mean of 0.60. See Table 1 for factorial solution,

loadings, and item parameters.

The 3-factorial solution conformed to a simple factor struc-

ture except for items 03 and 17. It replicated factor I and factor

IV of the 4-factorial solution, but factor II and factor III of the

4-factorial solution fell together on one factor. In the 2-facto-

rial solution, the second factor replicated factor IV of the

4-factorial solution with only the addition of item 28. All other

items loaded on a strong first factor.

We considered the 4-factorial solution the most informative

one. The 3-factorial solution would have meant abandoning a

consistently positively worded scale (factor III of the 4-facto-

rial solution). As regards content, we considered a positively

worded scale as advantageous, so we wanted to keep it, given

sufficient structural stability. The 2-factorial solution seemed

to replicate a theoretical distinction of the stress construct into

perceived stressor (factor II) and stress reaction (factor I). We

ultimately decided to investigate the 4-factorial solution more

thoroughly and to include all three solutions in the confirma-

tory analyses.

TABLE 2. Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) of 2-, 3-, and 4-Factorial Solutions and Multi-Sample Analyses (MSA) of the 4-Factorial Solution

of 20 PSQ Items From Sample 2 (n 1,808)

Model

Model-test Fit Statistics

a

2

df Cmin/df GFI AGFI RMR TLI CFI RMSEA

2

/df

b

CFA

2 factors 2,834.6 169 16.77 .83 .78 .007 .85 .86 .090

3 factors 2,310.0 167 13.83 .86 .83 .007 .87 .89 .087 524.6/2

4 factors 1,921.8 166 11.58 .89 .86 .006 .90 .91 .079 388.2/1

MSA 3 groups

c

Restricted 4,302.7 538 8.00 .92 .93 .064

Unrestricted 3,381.6 500 6.76 .93 .95 .058 921.1/38

MSA 4 groups

d

Restricted 4,424.8 723 6.12 .92 .93 .055

Unrestricted 4,306.5 685 6.29 .92 .93 .056 118.3/38

MSA 5 groups

e

Restricted 4,615.5 908 5.08 .92 .93 .049

Unrestricted 4,443.9 870 5.11 .92 .94 .049 171.6/38

a

Fit statistics: GFI goodness of fit index; AGFI adjusted goodness of fit; RMR root mean squared residual; TFI Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI

comparative fit index; RMSEA root mean standard error of approximation.

b

2

df difference in chi-square by df (all p .001).

c

Ill (mental/behavioral, tinnitus, IBD) vs. pregnant vs. healthy.

d

Somatically ill (tinnitus, IBD) vs. mentally/behaviorally ill vs. pregnant vs. healthy.

e

Suffering from tinnitus vs. IBD vs. mental/behavioral illness vs. healthy vs. pregnant.

Figure 1. Linear structural equation model of a 4-factor solution based on

one latent construct of perceived stress

H. FLIEGE et al.

82 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

We then selected those 5 items of each scale that showed

the highest corrected item-scale-correlation (Table 1). Thus, a

20-item questionnaire of 4 scales with 5 items each resulted.

Scale 1 (worries) covers worries, anxious concern for the

future, and feelings of desperation and frustration.

Scale 2 (tension) explores tense disquietude, exhaustion,

and the lack of relaxation.

Scale 3 (joy) is concerned with positive feelings of chal-

lenge, joy, energy, and security. Because all items of this scale

are positively worded, we opted for a positive name.

Scale 4 (demands) covers perceived environmental de-

mands, such as lack of time, pressure, and overload.

An overall index score is calculated from all items, and

linearly transformed to values between 0 and 1. For this purpose,

the scale joy, which is positively coded, will be inversed. A

high overall PSQ score means a high level of perceived stress.

Although all PSQ scales intercorrelate fairly highly, demands,

which focuses on external stressors, shows the lowest correlations to

the other three scales, which focus on the stress reaction (Table 3).

Confirmatory analyses, validation, and usability testing

were all performed on the resulting 20-item questionnaire.

Confirmation

Following the above cited theoretical concepts (2), SEM

was constructed as shown in Figure 1. Thus, the tested 4-fac-

tor solution specifies an additional latent variable stress re-

action loading on the first 3 factors (worries, tension, joy)

and covarying with demands. This resulted in a significant

likelihood-ratio

2

test (Table 2) with a global fit index (GFI)

below 0.95 and an adjusted GFI below 0.90. However, be-

cause Hoelters critical number (here 176) is considerably

smaller than the sample size, any model would inevitably have

been rejected applying those indices. Thus, we followed a

recommendation to judge a model by a number of different

criteria (25). The root mean squared residual below 0.05 is a

criterion in favor of the model fit. Furthermore, the Tucker-

Lewis index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI)

reached good values (0.90). Both are independent of sample

size and either take into account model complexity (TLI) or

model misspecification (CFI). Finally, a value of about 0.08 or

less for the root mean standard error of approximation is

considered to indicate a reasonable fit (26). This index allows

for discrepancies between sample and population. Taking all

this into account, we consider the model fit satisfactory.

Only the path weight between item 29 and demands fails

to satisfy (0.47). This might be due to a positive item wording.

A tentative exclusion of the item does not result in a closer

model fit. The lowest path weight results for the overall

sample, whereas in the subgroups this weight varies between

0.54 and 0.60. Because this item had a high loading in the

original exploratory factor solution (0.72) and seems unprob-

lematic as to content, we decided to keep it.

Multisample analyses yield that there is no appreciable gain

in model fit by omitting the restriction of structural equality

between groups. In sum, they confirm the assumption of a

comparable dimensional structure in different samples.

Reliability

Cronbachs alpha and split-half reliability values of the

scales in the subgroups are all at least 0.70, in half the cases

at least 0.80. Cronbachs alpha of the overall score is at least

0.85 and reliability at least 0.80 (Table 4).

TABLE 3. PSQ Scale Intercorrelations and Correlations Between PSQ and WHOQOL-Bref (n 650) and PSQ and TICS (Trier Inventory of

Chronic Stress) (n 559)

PSQ Scales

Worries Tension Joy Demands Overall Score

PSQ

Worries .67 .61 .51 .86

Tension .63 .57 .87

Joy .36 .78

Demands .76

WHOQOL-Bref

Physical domain .58 .64 .62 .24 .62

Psychological domain .78 .69 .79 .33 .79

Social domain .56 .50 .63 .25 .59

Environmental domain .60 .48 .55 .23 .57

Global QoL score .58 .56 .63 .17 .58

TICS

Work overload .61 .61 .44 .83 .77

Work discontent .51 .45 .49 .42 .57

Social stress .52 .39 .32 .45 .52

Lack of social recognition .51 .37 .46 .36 .52

Worries .80 .67 .61 .55 .81

Intrusive memories .66 .51 .45 .37 .61

Notes: Joy values are positively coded (except for the overall score). All Pearson correlations p .001. WHOQOLs Cronbachs alpha: physical 0.81;

psychological 0.88; social 0.70; environmental 0.79; global QOL score 0.62. TICS Cronbachs alpha: work overload .88, work discontent .76, social stress .76,

lack of social recognition .85, worries .88, intrusive memories .91.

PERCEIVED STRESS QUESTIONNAIRE

83 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

Construct Validity

Stress scales and overall score are negatively correlated,

and the joy scale is positively correlated with quality of life

(QoL) dimensions (p .001) (Table 3). All PSQ scales

correlate more highly with the psychological domain of the

WHO-QOL than with other WHO-QOL domains. The corre-

lational pattern with the TICS is altogether consistent with

expectation. Five of the 6 TICS subscales are most highly

TABLE 4. Mean Values and Consistency Values in Different Subgroups of Sample 1 (n

1

650) and Sample 2 (n

2

1,808), n

overall

2,458

Samples

PSQ Scales

Overall

Worries Tension Joy Demands

Sample 1

Psychosomatic in-patients n 246

M .53 .48 .37 .44 .52

SD .26 .12 .23 .16 .18

Crohnbachs alpha .83 .80 .83 .79 .85

r Spearman-Brown .84 .79 .82 .79 .87

Females after spontan. abortion n 81

M .34 .44 .56 .41 .41

SD .25 .23 .22 .21 .19

Crohnbachs alpha .83 .83 .75 .79 .92

r Spearman-Brown .88 .78 .77 .83 .88

Females after regular delivery n 74

M .23 .36 .65 .38 .33

SD .19 .22 .21 .21 .17

Crohnbachs alpha .79 .82 .77 .77 .91

r Spearman-Brown .76 .76 .77 .71 .85

Students n 249

M .26 .40 .60 .43 .37

SD .18 .21 .21 .23 .17

Crohnbachs alpha .77 .83 .82 .81 .92

r Spearman-Brown .76 .83 .85 .73 .84

Sample 2

Psychosomatic out-patients n 559

M .60 .66 .37 .47 .59

SD .27 .23 .21 .25 .19

Crohnbachs alpha .86 .81 .77 .82 .92

r Spearman-Brown .86 .75 .80 .77 .83

Tinnitus patients n 184

M .41 .54 .47 .44 .48

SD .25 .23 .24 .24 .21

Crohnbachs alpha .89 .84 .87 .81 .94

r Spearman-Brown .88 .82 .87 .79 .87

IBD patients n 144

M .35 .47 .51 .40 .43

SD .21 .20 .22 .22 .17

Crohnbachs alpha .79 .77 .79 .82 .90

r Spearman-Brown .80 .70 .76 .79 .80

Pregnant females 8

th

week n 587

M .23 .37 .64 .37 .33

SD .18 .20 .20 .19 .16

Crohnbachs alpha .81 .79 .76 .76 .90

r Spearman-Brown .78 .73 .81 .73 .85

Healthy adults n 334

M .26 .34 .62 .36 .33

SD .20 .21 .21 .21 .17

Crohnbachs alpha .83 .81 .79 .80 .92

r Spearman-Brown .81 .77 .79 .77 .86

ANOVA

df 8;2,393 8;2,389 8;2,381 8;2,392 8;2,329

F value 136.5 101.3 90.2 11.8 102.1

Explained variance

2

31% 25% 23% 4% 26%

p .001 .001 .001 .001 .001

Note: Scale values are linearly transformed from 14 to 01. Joy is inverted when computing the overall PSQ score.

H. FLIEGE et al.

84 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

correlated with the same PSQ scale (worries), whereas the

TICS work overload scale is most strongly related to the PSQ

demands scale.

Comparison to the Original

In the 650 subjects who completed the full questionnaire,

the correlation between the 30-item overall score and the

20-item overall score was high (r 0.95, p .001). To

examine whether the level of the overall score and its mea-

surement consistency were maintained in spite of the item

reduction, we compared the gastroenterological sample of the

original study (including many ulcerative colitis patients) with

the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) sample of the present

study. Internal consistency of the original and the revised

version is identical ( 0.90). Mean values and distribution

of the overall stress score of the original (0.42 0.15, range

0.110.83) and the revised questionnaire (0.43 0.17, range

0.020.87) do not differ. Mean values and distribution of the

overall stress score of healthy adults in a Spanish validation

(16) of the 30-item PSQ (0.35 0.14, range 0.080.86) and

the healthy adults in the German revision (0.33 0.17, range

0.000.85) also do not differ.

Group Differences

Values are listed in Table 4, and differences are roughly

summarized in Figure 2 (see Table 5 for details). All scales

differed between patients and healthy adults. The extent of the

differences varies with the scale and the group in question.

The most severe stress values are obtained from Psychoso-

matic Medicine patients, especially outpatients, followed by

tinnitus patients. Both groups have higher stress levels than

IBD patients and women after spontaneous abortion, who

report the second highest. Next in line are students, pregnant

women, and women after regular delivery. Consistently low

stress levels are reported by healthy adults. Students selec-

tively report high levels of demands. Pregnant women and

women after regular delivery show the highest levels of joy

and the lowest levels of worries. When controlled for age, they

even have significantly better values than healthy controls.

Sociodemographic Variables

Sociodemographic differences were tested on the healthy

adults sample (n 334). All scales are significantly associ-

ated with age (worries r 0.14*, tension r 0.25**, joy

r 0.14**, demands r 0.31**, overall score r

0.28**), but not with gender. Figure 3 presents differences

between age groups. Perceived stress is diminished and joy is

raised in age groups over 60 years. Only worries are slightly

lessened in the 60s group but no longer significantly in the 70s

and older. Demands are selectively elevated in the 30- to

39-year-olds.

Criterion Validity

To test for immunological differences, women after mis-

carriage were divided in two stress groups by median-split.

Decidual tissue for immunohistochemistry could be obtained

in 50 cases. Women with a higher stress score had a signifi-

cantly higher rate of tryptase

mast cells (TMC

), of CD8

T-cells, and of TNF-

cells (Figure 4). No differences re-

sulted with regard to CD56

NK-cells and CD3

T-cells. In

sum, higher perceived stress scores are associated with some

of the relevant indicators of a supposed immunological im-

balance in women who have had a miscarriage (22).

Sensitivity of Change

Psychosomatic Medicine inpatients under treatment show

significant improvements for three of the stress scales and the

overall score, but no change for joy. Tinnitus patients after 10

weeks of relaxation training (27) show a significant decrease

of tension and an increase of joy, whereas worries and de-

mands remain unchanged (Figure 5).

Usability

It took respondents on average 4.9 minutes to complete the

revised 20-item questionnaire. The time median was 3.3 minutes.

Only 5% of the patients took longer than 10 minutes; a few of

those took up to an hour. We could not find any differences

between diagnostic groups. There also was not any indication of

a language effect in non-German-born participants. Age was

significantly correlated with time-to-complete (r 0.28). The

stress scores themselves were slightly negatively (!) correlated

with time (between r 0.05 and 0.06), the less stressed

patients taking more time to complete, yet when controlling for

age, this association disappeared.

Figure 2. Tentative summary of the PSQ mean differences between samples

by post hoc t tests (p .05). (Note: a complete overview of the comparisons

can be requested from the authors.)

Figure 3. Mean differences between age groups for different dimensions of

perceived stress (PSQ scales)

PERCEIVED STRESS QUESTIONNAIRE

85 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

DISCUSSION

The PSQ by Levenstein et al. (14) was revised and tested for

its dimensional structure on a large sample. We reduced the

length of the questionnaire from 30 to 20 items and explored a

meaningful and widely stable structure. The scales are balanced

in the sense of comprising of the same number of items. Reli-

ability values and construct validity are satisfactory.

Exploratory analyses were performed on one sample, con-

firmatory analyses on a second and separate sample. The

original 7-factor solution was not replicated when the com-

plete 30-item scale was analyzed. Instead, a 4-factor solution

emerges. SEM analyses confirm this structure. Multisample

analyses yield a sufficiently stable dimensional structure

across different subgroups of patients and healthy adults. On

the whole, the structure appears statistically robust and satis-

factory as regards content. Consequently, in our opinion, the

problem concerning the path weight between item 29 and the

demands factor can be considered of minor importance and

does not justify a modification. A trend toward comparably

lower path weightsas can also be observed in items 01 and

10might arise from positive item wordings. However, con-

sidering that mixed item wordings have advantages of their

own, such as representing various facets of the latent construct

or keeping subjects attentive, we do not endorse abandoning

the positively worded items.

The dimensional structure is meaningful. Three factors

(worries, tension, and joy) represent the dimension of stress

reactions. In our opinion, the positively coded joy scale could

assess a positive challenge or a personal resource component.

The fourth factor (demands) represents a specific aspect of

perceived environmental stressors. That the demands scale has

a different focus than the three other scales is also proven by

lower correlations of demands with the remaining scales. To

regard the demands scale as focusing on an environmental

dimension of perceived stress and the other scales as focusing

on perceived stress reactions would be in line with findings

from earlier studies in which the persons perception of stress

was best represented by the two global dimensions of external

stressor and stress reaction (2). Differential validity of the

demands scale is supported by two findings: Students report

higher levels and older adults report lower levels of demands.

Demands can be considered external stressors (8,21). How-

ever, the scale does not claim to cover all possible external

stressors. Item topics are confined to the perception of basic

demands on ones performance, like having too many things

to do or being under time pressure. We do not know what

specific demands a person who scores high on that scale has

in mind. Specific hassles or life events are not included in this

questionnaire.

Furthermore, an explicitly social component of environ-

mental stressors is not included. For instance, out of the

original harassment scale, which had dealt specifically with

interpersonal tensions, only one of four items remained (You

feel that too many demands are being made on you). The

harassment scale had originally explained the greatest share of

variance (15%) and it had strongly correlated with physical

outcome. This is a possible limitation of the briefer PSQ. In

sum, construct validity results point out that the psychological

component of perceived stress is well represented by the

20-item PSQ, whereas the social component is not. Therefore,

studies that strongly focus on social stress issues should prefer

the use of the original 30-item questionnaire.

Future research could endeavor to strengthen and differen-

tiate the stressor side of the questionnaire and to economize

the stress reaction side with the aim to assess both sides of the

coin accurately and economically. The relative merits of pre-

senting a specific time frame, as in the original PSQ, or

leaving it open-ended, as in the instructions for this revision,

Figure 4. Immunological differences between women with high versus low

stress scores after miscarriage (median-split; t tests, ES effect size d)

Figure 5. Changes of perceived stress of Psychosomatic Medicine in patients

after psychotherapeutic treatment (left) and of tinnitus patients after relaxation

training (right) (t tests for dependent measures, ES effect size d)

H. FLIEGE et al.

86 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

also remain to be assessed. As the time-frame depends on the

specific research question, future research should specify and

compare different time-frames.

Comparisons of PSQ index values between gastroenter-

ological samples of the study by Levenstein et al. (14) and the

present study yield no differences in measurement precision or

respondents scoring. This indicates thatconcerning the in-

dex scorethe revised German version of the questionnaire

reaches the same precision as the English original, with com-

parable results. In the original study, Levenstein et al. (14)

observed higher values for Italian than for English respon-

dents. Considering our own results, we do not expect great

deviations between German and English-speaking samples,

yet we consider a confirmation of the revised questionnaire

with an English-speaking sample desirable. Only if structural

invariance between samples from different cultural or lingual

backgrounds was substantiated could we confidently use the

instrument for studies across cultures.

Similar to the original questionnaire, the revised instrument

does not significantly vary with respect to gender. This is not

consistent with other research, which yields higher perceived

stress scores for women (17,20). An explanation for this could be

TABLE 5. Comparisons Between Samples by Post-hoc t Tests (p < .05)

Post Hoc Comparisons

p t i a g d s h

Worries

Psychosomatic patients p

Tinnitus t

Inflammatory bowel dis. i

Spontaneous abortion a

Gravidity 8th week g

Delivery d

Students s

Healthy adults h

Tension

Psychosomatic patients p

Tinnitus t

Inflammatory bowel dis. i

Spontaneous abortion a

Gravidity 8th week g

Delivery d

Students s

Healthy adults h

Joy

Psychosomatic patients p

Tinnitus t

Inflammatory bowel dis. i

Spontaneous abortion a

Gravidity 8th week g

Delivery d

Students s

Healthy adults h

Demands

Psychosomatic patients p

Tinnitus t

Inflammatory bowel dis. i

Spontaneous abortion a

Gravidity 8th week g

Delivery d

Students s

Healthy adults h

Overall score

Psychosomatic patients p

Tinnitus t

Inflammatory bowel dis. i

Spontaneous abortion a

Gravidity 8th week g

Delivery d

Students s

Healthy adults h

Note: greater, smaller, no significant difference (left column compares to right).

PERCEIVED STRESS QUESTIONNAIRE

87 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

that the original PSQ was specifically designed and developed to

ensure that men and women would have similar scores (14).

As to age, the original study yielded a relatively small

correlation between the overall score and age (r 0.22). In

the present study, the association with age is reversed (r

0.28). This might be due to the fact that among the former

sample, older age groups were underrepresented (mean age

was 32), whereas the sample of the present study covers all

age groups. Here, group differences suggest that the demands

values are slightly higher for the 30- to 39-year-olds compared

with the 20- to 29-year-olds. This would be in line with the

former findings. However, the overall stress score is appre-

ciably lowest for the age groups above 60 years. Those groups

were hardly represented in the original study.

Reference values for healthy adults and different disease

groups were attained. We found particularly high stress levels

in Psychosomatic Medicine patients, followed by patients with

tinnitus and IBD and women after spontaneous abortion.

Women in pregnancy or after regular delivery and healthy

adults report the lowest stress levels. The data prove differ-

ential validity. Decreased levels of perceived stress after dif-

ferent forms of treatment in different settings sufficiently

substantiate sensitivity to change.

In sum, our revision of the PSQ arrived at an economic,

reliable, structurally stable and valid instrument that enables

us to assess perceived stress in healthy adults and different

disease groups. It measures three dimensions of a stress reac-

tion (worries, tension, joy/reversed) and one stressor dimen-

sion. Because the stressors are generic, the questionnaire can

be administered to different clinical and healthy adult samples

in different settings. Results can be compared with the refer-

ence values at hand and across studies. The overall score is

comparable to results from earlier studies with the original

instrument (14,16). The original 30-item questionnaires

structure was not replicable, whereas the 20-item versions

structure proved reasonably robust. Taking this advantage and

respondent burden into account, we suggest that the 20-item

version is preferable. However, it means that notably the

social stressor domain is not sufficiently represented. Further-

more, future research should also investigate how a corre-

sponding 20-item English version of the PSQ would perform.

We wish to thank Ingrid Wittmann, Urania Berlin, and Jan Schwen-

dowius for their assistance in raising the healthy adult sample, and

especially Dr. Susan Levenstein for her many helpful comments on

the paper.

REFERENCES

1. Kenny DT, Carlson JG, McGuigan FJ, Sheppard JL. Stress and health:

research and clinical applications. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic; 2000.

2. Lobel M, Dunkel-Schetter C. Conceptualizing stress to study effects on

health: environmental, perceptual, and emotional components. Anxiety

Res 1990;3:21330.

3. Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon GL. Strategies for measuring stress. In:

Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU, editors. Studies of psychiatric and

physical disorders in measuring stress. New York: Oxford University

Press; 1995. p. 326.

4. Adler CM, Hillhouse JJ. Stress, health, and immunity: a review of the

literature. In: Miller T, editor. Theory and assessment of stressful life

events. Madison: International Universities Press; 1996. p. 10938.

5. Critelli J, Ee J. Stress and physical illness: development of an integrative

model. In: Miller T, editor. Theory and assessment of stressful life events.

Madison: International Universities Press; 1996. p. 13959.

6. Searle A, Bennett P. Psychological factors and inflammatory bowel disease:

a review of a decade of literature. Psychol Health Med 2001;6:12135.

7. Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP. Socioenvironmental factors, stress,

and psychopathology. Am J Comm Psychol 1981;9:12859.

8. DeLongis A, Coyne JC, Dakof G, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Relationship

of daily hassles, uplifts, and major life events to health status. Health

Psychol 1982;1:11936.

9. Lazarus RS, Folkman S: Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York:

Springer; 1984.

10. DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health

and mood: psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc

Psychol 1988;54:48695.

11. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived

stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;1983:38596.

12. Derogatis LR, Coons HL: Self-report measures of stress. In: Goldberger

L, Breznitz S, editors. Handbook of stress: theoretical and clinical as-

pects. New York: The Free Press; 1993. p. 20033.

13. OKeefe MK, Baum A. Conceptual and methodological issues in the

study of chronic stress. Stress Med 1990;6:10515.

14. Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C,

Andreoli A. Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: a new

tool for psychosomatic research. J Psychosom Res 1993;37:1932.

15. Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Andreoli A, Luzi C,

Arca` M, Berto E, Milite G, Marcheggiano A. Stress and exacerbation in

ulcerative colitis: a prospective study of patients enrolled in remission.

Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1213220.

16. Sanz-Carrillo C, Garcia-Campayo J, Rubio A, Santed M, Montoro M.

Validation of the Spanish version of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire

(PSQ). J Psychosom Res 2002;52:16772.

17. Bergdahl J, Bergdahl M. Perceived stress in adults: prevalence and

association of depression, anxiety and medication in a Swedish popula-

tion. Stress Health 2002;18:23541.

18. Wachirawat W, Hanucharurnkul S, Suriyawongpaisal P, Boonyapisit S,

Levenstein S, Jearanaisilavong J, Atisook K, Boontong T, Theerabutr C.

Stress, but not Helicobacter pylori, is associated with peptic ulcer disease

in a Thai population. J Med Assoc Thai 2003;86:67285.

19. Abell N. The Index of Clinical Stress: a brief measure of subjective stress

for practice and research. Soc Work Res Abstracts 1991;27:126.

20. Koh KB, Park JK, Kim CH, Cho S. Development of the Stress Response

Inventory and its application in clinical practice. Psychosom Med 2001;

63:66878.

21. Schulz P, Schlotz W. Trierer Inventar zur Erfassung von chronischem

Stre (TICS). Diagnostica 1999;45:819.

22. Arck P, Rose M, Hertwig K, Hagen E, Hildebrandt M, Klapp BF. Stress

and immune mediators in miscarriage. Human Reprod 2001;16:150511.

23. Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, Levenstein S, Klapp BF. Validierung des

Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) an einer deutschen Stichprobe.

Diagnostica 2001;47:14252.

24. Angermeyer MC, Kilian R, Matschinger H: WHOQOL-100 und WHO-

QOL-BREF. Gottingen: Hogrefe; 1999.

25. Breivik E, Olsson U. Adding variables to improve fit: the effect of model

size on fit assessment in LISREL. In: Cudeck R, du Toit S, Sorbom D,

editors. Structural equation modeling. Lincolnwood: Scientific Software

International; 2001. p. 169194.

26. Browne M, Cudeck R: Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen

K, Long J, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park:

Sage; 1993. p. 136162.

27. Weber C, Arck P, Mazurek B, Klapp BF. Impact of a relaxation training

on psychometric and immunologic parameters in tinnitus sufferers. J Psy-

chosom Res 2002;52:2933.

H. FLIEGE et al.

88 Psychosomatic Medicine 67:7888 (2005)

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- Handbook of Metric Drive ComponentsDokumen228 halamanHandbook of Metric Drive ComponentsbubickaBelum ada peringkat

- Executive Program Application: S A General InformationDokumen4 halamanExecutive Program Application: S A General InformationbubickaBelum ada peringkat

- RR 174Dokumen249 halamanRR 174bubickaBelum ada peringkat

- T&P Methodology For Implementation of ISMS v2Dokumen10 halamanT&P Methodology For Implementation of ISMS v2bubickaBelum ada peringkat

- T&P Methodology For Implementation of IQISMS v3Dokumen10 halamanT&P Methodology For Implementation of IQISMS v3bubickaBelum ada peringkat

- T&P Methodology For Implementation of IQISMS v3Dokumen10 halamanT&P Methodology For Implementation of IQISMS v3bubickaBelum ada peringkat

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5782)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (72)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- PCWHS SSG PPAs Progress Report 2021 2022Dokumen62 halamanPCWHS SSG PPAs Progress Report 2021 2022Tanglaw Laya May PagasaBelum ada peringkat

- Very Good CBSE Class 7 Social Science Sample Paper Set CDokumen8 halamanVery Good CBSE Class 7 Social Science Sample Paper Set CAmrita SenBelum ada peringkat

- II. Review of Related Literature 2.1 Foreign: Case 1: The Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park (Tokyo, Japan)Dokumen7 halamanII. Review of Related Literature 2.1 Foreign: Case 1: The Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park (Tokyo, Japan)Mr. ManaloBelum ada peringkat

- WPDS Country Profile WorksheetDokumen1 halamanWPDS Country Profile WorksheetPaula Sabater0% (1)

- General Roles and Responsibilities of Nurses in The Regional Blood CenterDokumen2 halamanGeneral Roles and Responsibilities of Nurses in The Regional Blood CenterKarlos Kanapi0% (1)

- Plan a Health Career PathDokumen4 halamanPlan a Health Career PathIsrael Marquez100% (3)

- Removal of CatheterDokumen2 halamanRemoval of CatheterMargaret ArellanoBelum ada peringkat

- Breast anatomy overviewDokumen59 halamanBreast anatomy overviewgina2535100% (1)

- PD0B-501 Details of Test Code For System PackDokumen2 halamanPD0B-501 Details of Test Code For System PackVikram SinghBelum ada peringkat

- The Truth About EtawahDokumen4 halamanThe Truth About EtawahPoojaDasgupta100% (1)

- Southlands School - BournemouthDokumen15 halamanSouthlands School - BournemouthAngela SimaBelum ada peringkat

- XPDokumen290 halamanXPArun Surendran100% (1)

- Diet Ant PDFDokumen3 halamanDiet Ant PDFAnonymous ZvBtfvBelum ada peringkat

- #14 Overhead WorkDokumen1 halaman#14 Overhead WorkAchmad MahatdzirBelum ada peringkat

- P504 Work PackDokumen16 halamanP504 Work PackFernando SantosBelum ada peringkat

- Brain Development in ChildrenDokumen2 halamanBrain Development in ChildrenBal BantilloBelum ada peringkat

- Case Scenario 1 PDFDokumen11 halamanCase Scenario 1 PDFMariano MarbellaBelum ada peringkat

- Universidad Santo Tomás - Carrera de Psicopedagogía - 1a Solemne NeurodidácticaDokumen4 halamanUniversidad Santo Tomás - Carrera de Psicopedagogía - 1a Solemne NeurodidácticaPatricio Andrés BelloBelum ada peringkat

- KaizenDokumen13 halamanKaizenVlado RadicBelum ada peringkat

- CardiomyopathyDokumen23 halamanCardiomyopathyDefyna Dwi LestariBelum ada peringkat

- Control1088un 2020-01 PDFDokumen104 halamanControl1088un 2020-01 PDFhareshBelum ada peringkat

- Air PollutionDokumen16 halamanAir Pollutionvgs127350% (2)

- Uv Light Form Old ControlDokumen7 halamanUv Light Form Old ControlAnonymous m0vmAykBelum ada peringkat

- CJN 079Dokumen199 halamanCJN 079SelvaArockiamBelum ada peringkat

- Adhd Nutrition Considerations ChecklistDokumen1 halamanAdhd Nutrition Considerations Checklistapi-235820714Belum ada peringkat

- Endoftalmitis EndogenaDokumen1 halamanEndoftalmitis EndogenaAlexander Fabián Rodríguez DíazBelum ada peringkat

- Infection Control and Prevention Program ImplementationDokumen1 halamanInfection Control and Prevention Program ImplementationAhmad Ali ZulkarnainBelum ada peringkat

- Brigada Eskwela Evaluation Tool: A. SCOPE OF WORK 30% (Please Include The Quantity)Dokumen5 halamanBrigada Eskwela Evaluation Tool: A. SCOPE OF WORK 30% (Please Include The Quantity)Jofit DayocBelum ada peringkat

- G - P - 69 Form MedicalDokumen2 halamanG - P - 69 Form MedicalErick AmattaBelum ada peringkat

- Vegan. The Healthiest Diet. Henrich, Ernst WalterDokumen42 halamanVegan. The Healthiest Diet. Henrich, Ernst Walteralice1605Belum ada peringkat