Bopreport 5

Diunggah oleh

rachna357Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Bopreport 5

Diunggah oleh

rachna357Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Exchange rate depreciation and the trade balance in

South Africa

Lawrence Edwards and Owen Willcox

Executive Summary

This study assesses the impact of exchange rate movements on the South African trade

balance. In particular, it analyses whether a depreciation of the currency can improve the

trade balance through promoting export production and import substitution? This

relationship is of central importance to the GA! macroeconomic strategy, which aims to

improve export growth through maintaining a stable and competitive real effective exchange

rate.

The study follows much international empirical research and uses the elasticity approach to

analyse the responsiveness of exports and imports to exchange rate movements. The study

draws upon the "ic#erdi#e$!obinson$%et&ler '"!%( condition which defines a set of

necessary conditions on the si&e of import demand, import supply, export demand and

export supply elasticities for a depreciation to improve the trade balance. "ecause of

limitations with this approach, additional relationships, such as the feedbac# of a

depreciation into domestic inflation, are also incorporated into the analysis.

Export and import performance

The study finds that export and imports remained relatively stable during the )*+,s and

early )*-,s, but grew strongly from the mid$)*-,s. xport growth was particularly strong

within manufacturing which has become the dominant source of export revenue, accounting

for ./ 0 of total exports 'excluding services( in 1,,,. Indicators of openness 'exports and

imports as a share of G23, import penetration and export orientation( have also risen

sharply, reflecting the rising importance of international trade for the domestic economy.

4or example, manufacturing exports as a share of output grew from ),.1 0 in )*-5 to 1+.5

0 in 1,,,. Similar strong growth in imports raised import penetration 'imports as a share of

consumption( from )- 0 in )**, to 61 0 in 1,,,.

The manufacturing trade balance has also improved during this period. In contrast, the

merchandise trade balance worsened which largely reflects the decline in gold exports. The

improvement in the manufacturing trade balance since the mid$)*-,s coincides with a

depreciation of the domestic currency. Although the exchange rate depreciation may have

contributed towards this improvement, numerous other policy changes ma#e it difficult to

identify the relative importance of the depreciation. 4or example, the Generalised xport

Incentive Scheme 'GIS( raised export production through subsidies. Trade liberalisation,

which accelerated from )**/, has substantially improved the profitability of export

production by reducing the cost of domestic and imported intermediate goods used in the

production process. 4inally, the ending of sanctions and the re$integration of South Africa

into the international mar#et have further enhanced export performance.

)

Theoretical considerations

Theoretically, an exchange rate depreciation has an ambiguous impact on the trade balance.

7n the import side, a depreciation raises the domestic price of imported products.

8onsumers and producers respond by substituting domestic for imported goods. 9owever,

the extent to which this substitution is possible is dependent on the availability of similar

domestically produced importing$competing products as well as the time period subse:uent

to the depreciation. %any developing economies are highly dependent on imported

intermediate 'such as oil or li:uid fuel( and capital goods used in the production process.

These economies lac# a wide range of substitutes for these imported products implying a

highly inelastic import demand function. ven if substitutes are available, ;lags in

recognition of the changed situation, in the decision to change real variables, in delivery

time, in the replacement of inventories and materials, and in production< give rise to an

inelastic demand curve in the short run '%agee, )*+6= 6,+(. In these cases a depreciation

raises the domestic currency value of imports, that may persist even in the long run.

9owever, the maximum increase in the domestic currency value of imports, which occurs

when import demand is perfectly inelastic, is the depreciation rate.

7n the export side, a depreciation raises the home price and>or lowers the foreign currency

price of domestic exports. The extent to which the depreciation is passed on to foreign

consumers in the form of lower foreign currency prices of exports 'their imports( depends

on the elasticities of export supply and demand. In a small country model, export firms are

price ta#ers in the international mar#et 'they face an infinite demand for exports( and the

domestic currency price of exports rise by the full depreciation. The response in exports to

the depreciation depends on the elasticity of supply= the greater the elasticity, the greater the

rise in exports. In all cases, however, the domestic currency value of exports rises by at least

the depreciation rate. Thus, in small countries a depreciation improves the trade balance.

In contrast, in an economy with excess capacity in the export sector, the depreciation is fully

passed$through to foreign consumers, i.e. the !and price of exports remain constant, but the

foreign currency price of South African exports fall by the full depreciation. In this case, the

response in exports depends on the elasticity of export demand. If export demand is highly

inelastic, export volumes, and thus the domestic currency value of exports, only rise by a

small amount. This leads to the well$#nown %arshall$?erner condition which states that if

both supply curves are perfectly elastic and the trade balance is &ero, a devaluation of the

exchange rate worsens the trade balance if the sum of the demand elasticities is less than

one. This condition is more li#ely to be satisfied in the short run when import and export

demand curves are inelastic. Thus a depreciation may initially worsen the trade balance

prior to its improvement in the long run. This is #nown as the @$curve effect.

South African exports and imports account for approximately ,.1- 0 and ,./- 0 of world

trade, respectively 'dwards and Schoer, 1,,1(. In the long run, the most appropriate model

for the analysis in South Africa is thus li#ely to be the small country model in which a

depreciation improves the trade balance. 9owever, the short$run dynamics may differ

substantially. As shown in the %arshall$?erner relationship, inelastic import and export

demand curves, combined with elastic export supply responses, may result in an initial trade

deficit in the short run. In modelling the impact of the depreciation on the trade balance, it is

important to capture these short$run dynamics. "ecause of the importance of the small

country assumption in determining the impact of a depreciation on the trade balance, this

study analyses the pricing behaviour of South African exporters. The assumption that South

1

Africa is a price$ta#er in the import mar#et is less contentious and is widely assumed in

international empirical research 'Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5(.

Pricing behaviour of South African exporters

This study finds that South African exporters are price$ta#ers in the international mar#et, at

least during the )**,s. As a result, export prices rise by the full depreciation of the currency.

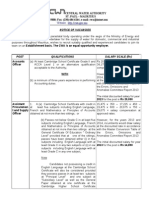

This is clearly shown in the calculated real effective exchange rates in 4igure A where

South African export prices are compared to a range of developed and developing country

export 'rerxuv(, consumer 'rercpi( and producer 'rerppi( prices, all measured in a common

currency.

)

Figure A: Real effective exchange rates using various price indices, uarterly data

As found in other studies 'see Golub, 1,,,(, the !! remained constant or rose during the

late )*+,s, but fell as the currency depreciated during the )*-,s. 3articularly large declines

occurred in )*-5 as a result of the nominal depreciation following the !ubicon speech and

the debt crisis. The decline, however, is greatest when comparing South African export

prices to foreign consumer prices. South African export prices appeared to follow foreign

export prices relatively closely. Thus, the average price of South African exports relative to

foreign export prices did not improve substantially during the )*+,s or early )*-,s. This is

consistent with a small country in which domestic export prices are set according to the

world mar#et. Similar trends are evident during the )**,s. !! calculated using foreign

83I show a continued decline during the )**,s. In comparison, the !! calculated using

foreign 33I or export unit values has not shown a substantial decline since )**/, despite the

depreciation of the currency. This arises because export prices rise by the full depreciation

rate.

This relationship is confirmed using econometric techni:ues. The domestic currency price

of South African exports closely follows the exchange rate, rising rapidly in response to a

depreciation. The estimated long$run elasticity of domestic$currency prices with respect to

)

The !! is a weighted average of the real exchange rate, Px/eP* where Px is South African export prices,

e is the !and>foreign currency exchange rate and P* is the foreign price index.

6

Log real effective exchange rates (1995=log(100))

4.00

4.20

4.40

4.60

4.80

5.00

5.20

5.40

M

a

r

-

7

5

M

a

r

-

7

7

M

a

r

-

7

9

M

a

r

-

8

1

M

a

r

-

8

3

M

a

r

-

8

5

M

a

r

-

8

7

M

a

r

-

8

9

M

a

r

-

9

1

M

a

r

-

9

3

M

a

r

-

9

5

M

a

r

-

9

7

M

a

r

-

9

9

M

a

r

-

0

1

rerppi rercpi rerxuv

the exchange rate ranges between ,.+ to ,.*. This implies that a ) 0 depreciation of the

currency raises export prices by between ,.+ 0 and ,.* 0. The close association between

export unit values and the exchange rate is consistent with the small$country model where

the pass$through to foreign prices is &ero.

The implication is that export growth in South Africa is driven by changes in the

profitability of export supply, rather than price competitiveness vis$B$vis foreign producers.

In other words, export growth in South Africa is not constrained by insufficient foreign

demand, but rather by insufficient export supply.

The small country behaviour of South African exporters suggests that a depreciation

improves the trade balance. 9owever, this study also finds that the improved profitability of

export production through a depreciation is fre:uently eroded by domestic inflation and

wage increases. 4or example, no long$run deviation between the exchange rate, export

prices and domestic prices is found. As a result, no sustained relationship between exchange

rate movements and the trade balance is found when using graphical analysis. 4or a

comprehensive analysis of the impact of the exchange rate on the trade balance, it is thus

imperative that feedbac# between the exchange rate and domestic prices is explicitly

accounted for.

Econometric analysis

xport supply and import demand functions are estimated for South African manufacturing

and merchandise 'excluding gold( trade. To estimate these elasticities, the @ohansen

%aximum ?i#elihood procedure for multivariate cointegration analysis is used '@ohansen,

)*--, )**1(.

The econometric estimates of the export and import functions suggest that a depreciation

improves the trade balance. The long$run export supply elasticities range between $).,5 and

$).)1 are similar for manufacturing and merchandise goods 'excluding gold(. 9olding all

other variables constant, this implies that a depreciation raises exports by ).,5 to ).)1 0 in

the long run. The long$run import demand elasticities range between $).5* and $1./6, which

also show that a depreciation, holding other variables constant, reduce imports substantially.

These import demand elasticities exceed those of other South African studies that range

between C,.-5 and C).)5 'Aahn, )*-+, Smal, )**. and SenhadDi, )**+(.

Given the estimated elasticities, the elasticity of the trade balance 'normalised by the value

of imports( with respect to a currency depreciation 'E

!

( can be calculated. The appropriate

"ic#erdi#e$!obinson$%et&ler '"!%( condition for a depreciation to improve the trade

balance in a small country is given by

1

, > "# $% ! E E E .

Substituting the long$run export supply elasticity 'E

$%

E ).)16( and the import demand

elasticity 'E

"#

E $).5*( for merchandise goods into this relationship gives a long$run

exchange rate elasticity of the trade balance e:ual to 1.+)6. This implies that a ) 0

depreciation improves the trade balance of non$gold merchandise goods by 1.+)6 0 of the

value of imports in the long run. The elasticity for manufacturing is similar at 1.*-6.

9owever, the impact estimated using the "ic#erdi#e$!obinson$%et&ler condition

exaggerates the impact of a depreciation on the trade balance as it does not ta#e into account

1

Fote that the balanced trade assumption is imposed on this condition.

/

the feedbac# into domestic prices, nor the dynamics surrounding the convergence to

e:uilibrium. An advantage of the @ohansen procedure used in this study, is that it allows for

the endogeneity of all variables included in the regressions. The regression results indicate

that both domestic and export prices are strongly influenced by changes in the exchange

rate. A ), 0 depreciation raises export prices and domestic prices by *.1 0 and -.). 0 in

the long run, respectively. The rise in inflation thus negates some of the improved

profitability of export production arising from a depreciation of the currency. Gage costs

are also shown to increase with a depreciation further reducing the relative profitability of

export production.

The interaction between the exchange rate, domestic prices, export price and export supply

are more clearly shown in the generalised impulse responses presented in 4igure ". The first

figure shows the response in export volumes 'HI7?(, export prices '3H(, domestic prices

'33I27%( and unit labour costs 'J?8( to a one standard error depreciation of the exchange

rate '!AT(. The second figure displays the response in import volumes '%I7?( gross

domestic expenditure 'G2%AT3(, domestic prices '33I27%( to a one standard error

shoc# in import prices '3I%3JI(. In each figure the data on the hori&ontal axis represent

:uarterly periods.

Figure !: "eneralised impulse responses for merchandise exports #excluding gold$ and

imports

As shown in the first figure, there is a positive impact effect 'concurrent period effect( of a

depreciation on export prices and export supply. The immediate impact on domestic prices

and unit labour costs is close to &ero, but as the depreciation feeds into the system, wages

and domestic prices rise, reaching their pea# at around + :uarters. The exchange rate also

5

enerali!ed "#pulse $esponse(s) to one S%E% shoc& in the e'uation for E$A(E

XVOL

PX

ERAE

PP!"OM

#L$

%&ri'&(

-0.005

0.000

0.005

0.010

0.015

0.020

0.025

0.030

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

enerali!ed "#pulse $esponse(s) to one S%E% shoc& in the e'uation for )"*)+,

MVOL

)"EM*P

PP!"OM

P!MP#V

%&ri'&(

-0.01

-0.02

-0.03

-0.04

0.00

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0 5 10 15 20 25 30

appreciates slightly from its initial shoc# and reverses the rise in export prices experienced

during the first / periods. xports rise sharply in the first period subse:uent to the exchange

rate depreciation, but decline rapidly relative to the initial shoc# in the subse:uent periods as

domestic price and wage increases erode export profitability. xports stabilise after

approximately + :uarters at a higher level than prior to the depreciation. 9owever, the new

level of exports is lower than it would have been if wages and domestic prices had not also

risen in response to the depreciation.

The dynamic process outlined in the second figure captures the impact of a shoc# in import

prices on the various variables. It does not directly capture the impact of a depreciation on

these variables. Fevertheless, in a small country a depreciation raises the domestic currency

price of import by the full depreciation rate. The figure is thus an indirect representation of

the impact of a depreciation on imports.

The concurrent effect a rise in import prices is a decline in import demand. In the

subse:uent period imports rise sharply, possibly in response to hoarding behaviour of

importers in the face of a currency depreciation. Imports only fall sharply in period /.

Import prices also feed into domestic prices, but slowly. Gross domestic expenditure

declines slightly as rising import prices negatively affect expenditure, production and

investment.

Together these relationships confirm that a depreciation can improve the trade balance, but

at the cost of increased inflation.

Policy conclusions

Several policy conclusions emerge from this study.

South African exporters are price%ta&ers in the international mar&et. As a

conse:uence, export growth is driven by the profitability of export supply, rather than price$

competitiveness vis$B$vis foreign producers. This does not imply that foreign prices are

unimportant. 4oreign price increases raise the profitability of export production and thereby

induce increases in the :uantity of exports supplied. A further implication, and of direct

relevance to this study, is that export prices rise :uic#ly in response to a depreciation rate

and rise by the full depreciation rate.

'nflation and (age gro(th undermine the positive impact of exchange rate

depreciation on the trade balance. A depreciation improves the trade balance by raising

the profitability of export supply and raising the cost of imports relative to domestically

produced products. 9owever, this is only sustainable if domestic price and wage increases

do not offset the relative price shifts that lead to increased export supply and demand for

import$competing products. If wages and domestic prices rise, as historical evidence

suggests it does, further depreciation of the currency will be re:uired to maintain the

improvement in the trade balance. This may lead to an inflation spiral.

A more important policy obDective is to reduce the volatility of the exchange rate.

"ecause South African exporters are price$ta#ers, exchange rate volatility translates directly

into profit volatility. This volatility is also shown in 4igure 8 which displays the price of

exports and domestic goods relative to unit labour costs. !ising ratios are a proxy for

improved profitability. As shown in the figure, profitability of export production is more

.

volatile than production for the domestic mar#et and is largely a result of exchange rate

movements.

Iolatility of profits increases the ris# associated with export production, particularly for

small businesses that do not have sufficient finances to hedge themselves against this ris#.

Jsing a national firm survey of South African manufacturing firms, dwards '1,,1( finds

that only 1- 0 of small firms export compared to +, 0 of large firms. Similar values are

found by 8handra et al. '1,,)( for the Greater @ohannesburg %etropolitan Area. The

entrance of small firms into the export mar#et is an important obDective to increase South

African export growth. Stable profits enabled by a stable currency may encourage entrance

of small firms into the export mar#et.

Figure ): Relative profitability indices

Fotes= 33I is the producer price index for South African output for domestic consumption. Jnit labour cost is

obtained from the !eserve "an# Kuarterly "ulletin.

Price and (age rigidity exacerbate the negative impact of an appreciation on export

supply. The impact of a depreciation and appreciation are not necessarily symmetrical and

are influenced by institutional structures that induce rigidities into the adDustment of wages

and domestic prices. 4or example, if wage and domestic price rise :uic#ly in response to a

depreciation, the gains to the trade balance will be short lived. In contrast, if wages and

prices are rigid downwards, an appreciation of the currency may lead to a sustained deficit

in the trade balance. 8urrent trends in domestic inflation suggest that prices have been slow

to adDust downwards in response to the appreciation of the currency from mid$1,,1. South

African exporters have thus faced falling export prices 'in !ands( combined with continued

increases in their costs of production. These trends compound one another leading to

significant reductions in export production. The sharp appreciation of the currency in 1,,1

and 1,,6 will thus have a severe negative impact on the trade balance.

)an a depreciation offset high domestic production costs, including labour costs, that

inhibit export gro(th* dwards and Golub '1,,1( show that a depreciation positively

boosts exports by reducing South African wages relative to other country wages measured

+

$elative profitabilit- index (1995=1)

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

1.6

1.8

M

a

r

-

7

0

M

a

r

-

7

2

M

a

r

-

7

4

M

a

r

-

7

6

M

a

r

-

7

8

M

a

r

-

8

0

M

a

r

-

8

2

M

a

r

-

8

4

M

a

r

-

8

6

M

a

r

-

8

8

M

a

r

-

9

0

M

a

r

-

9

2

M

a

r

-

9

4

M

a

r

-

9

6

M

a

r

-

9

8

M

a

r

-

0

0

M

a

r

-

0

2

Merc+a(,i-e Px.u(i/ 0a1&ur c&-/ PP!.u(i/ 0a1&ur c&-/

in a common currency. 9owever, improving labour cost competitiveness through

depreciation is not sustainable in the long run. 2epreciation of the currency reduces the real

wage of wor#ers, who then bargain for compensatory wage increases. dwards and Golub

'1,,1( show that the depreciation of the South African !and vis$B$vis other developing

country currencies during the )**,s failed to offset wage increases in many industrial

sectors, and in particular labour$intensive sectors.

Alternative approaches towards increasing export performance and competitiveness of

import competing firms need to be found. 3rofitability of export production can be

improved through enhanced productivity gro(th combined (ith (age moderation.

dwards and Golub '1,,1( show that both wages and productivity are important

determinants of export growth. This study also finds that high unit labour costs, arising from

low labour productivity and>or high wages, negatively affect export supply. 3olicy that

encourages productivity improvements combined with wage moderation will thus enhance

export growth.

There are a number of approaches to improving productivity growth. 4irstly, improvements

in education, particularly the :uality thereof, are essential long$run policy obDectives

necessary to raise the productivity of South AfricaLs labour force. In addition to enabling

real wage increase, productivity improvements will enhance South AfricaLs export

performance.

Increased investment in ne( technology and productive capacity is a further avenue

through which to improve labour productivity. Increased investment in new technology can

be encouraged through an accelerated program of tariff liberalisation. This lowers the

cost of access to foreign technology as well as induces productivity gains through increased

international competition. Gor# by @onsson and Subramanian '1,,,( has shown a positive

relationship between improved T43 growth and trade liberalisation. Ian Seventer '1,,)(

also notes that the reduction in tariff rates has substantially reduced the anti$export bias

arising from protection on intermediate goods used in the production process. ?ower

production costs and improved productivity will also increase entry of firms into the export

mar#et, and thus further enhance the diversification of exports shown by "lac# and Aahn

')**-(. Although it is feared that tariff liberalisation will negatively affect employment,

dwards '1,,)a( shows that employment creation through improved export growth

compensates for employment lost in import competing sectors.

-

Exchange rate depreciation and the trade balance in

South Africa

Lawrence Edwards and Owen Willcox

+, 'ntroduction

Since the early )*-,s South AfricaLs trade policy regime has shifted from one of import

substitution towards one of export orientation. This shift has been encouraged by trade

liberalisation, which accelerated in )**/ with tariff liberalisation, and the GA!

macroeconomic strategy that was explicitly expected to transform South Africa into a

;competitive, outward orientated economy< 'GA!, )**.(. An exchange rate policy to

#eep the real effective exchange rate stable at a competitive level formed a #ey part of the

GA! strategy. Implicit in this view is that lower real effective exchange rates enhance

international competitiveness and thus improve export performance.

2uring the late$)**,s the real effective exchange rate has shown a downward trend 'Golub,

1,,,(, but has been characterised by much volatility. At the same time export growth has

improved and there is consensus that the decline in the real effective exchange rate has

much to do with this. ?ess focus has been placed on the impact of the exchange rate on

imports. South African imports are highly capital intensive suggesting that the depreciation

of the currency will not necessarily reduce import volumes by a significant :uantity. The

domestic currency value of imports may rise with a depreciation offsetting the positive

impact that improved export growth has on the trade balance. Intermediate goods also

account for a high proportion of total South African imports. If domestic substitutes are

unavailable the responsiveness of import demand to a depreciation will further diminish.

%ore importantly, a depreciation raises the cost of imported intermediate inputs and thus the

price of domestic products. These cost increases can offset some of the gains in

competitiveness of both export and import$competing products achieved through a

depreciation of the currency. The feedbac# of the depreciation into domestic prices is thus

an important element in the adDustment process of the trade balance.

The importance of exchange rate movements on the economy has to come to fore during the

previous two years. The large depreciation in the currency towards the end of 1,,)

improved export competitiveness, but raised the cost of imported products and domestic

inflation. 2uring 1,,1 the currency appreciated, negating much of the improved

competitiveness. The overall impact of exchange rate movements such as these on the trade

balance is not clear. This study analyses the relationship between exchange rate movements

and the trade balance in more detail.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 1 discusses the economic theory guiding the

empirical analysis followed within this study. The impact of the exchange rate on the trade

balance is shown to be dependent on the elasticities of demand and supply within the export

and import mar#ets. Section 6 then presents an overview of the empirical methodologies

used in the international literature. Section / presents an overview of South African

empirical research on the impact of exchange rate changes on the trade balance as well as

the estimated trade elasticities. This is followed by a graphical analysis of South African

exports, imports and relative price trends in Section 5. The results of the econometric

*

estimates are presented in Section .. Section + briefly interprets the results and provides

some policy conclusions.

-, Theory

2.1 Introduction

Three approaches have been used to analyse the impact of exchange rate movements on the

trade balance= 'a( Aeynsian absorption approach, 'b( monetary approach and 'c( the

elasticity approach.

The Aeynesian based absorption approach and the monetary approach focus on the

macroeconomic lin#ages and identities, rather than the microeconomic relationships of the

elasticity approach. In the absorption approach, the national income accounting identity is

maintained, i.e.

6

'H$%( E M $ '8NING(.

This implies that the trade account can only improve if domestic output growth exceeds

domestic absorption '2unn and %utti, 1,,,= /6,(. A devaluation improves the trade balance

if the substitution towards domestic goods in response to the relative price shift boosts

output more than absorption. This is more li#ely in an economy characterised by excess

capacity where the Aeynesian multiplier effect wor#s. In an economy near full employment,

or one facing severe bottlenec#s in production, output is unli#ely to increase and the trade

balance can only improve if absorption declines. Inflationary pressures also undermine the

relative price shifts that induce an increase in export production and a decline in

consumption of imported goods.

In the monetarist approach, a balance of payments deficit is entirely a monetary

phenomenon caused by excessively expansionary monetary policy '2unn and %utt, 1,,,(.

A devaluation only has an effect on the balance of payments through its impact on the real

money supply. Thus, a devaluation improves the balance of payment by raising domestic

prices and thereby reducing the real money supply. 2evaluations fail if they are followed by

further increases in the nominal money supply that re$establish the original dise:uilibrium.

The long$run effect on the trade balance is thus ambiguous.

The elasticity approach is the most common approach used to assess the impact of

exchange rate changes on the current account. In this approach, the impact on the trade

balance is determined by the response of exports and imports to changes in prices arising

from movements in the exchange rate. The reaction in these mar#ets is thus a function of the

elasticities of supply and demand. As this is the approach followed in this study, the

following section analyses the elasticity approach in more detail.

2.2 The elasticities approach

Analysis using the elasticity approach is largely based on variants of the "ic#erdi#e$

!obinson$%et&ler '"!%( condition, and in particular the simplified %arshall$?erner '%?(

version of this condition. The "!% condition defines a set of necessary conditions on the

si&e of import demand, import supply, export demand and export supply elasticities that will

result in an improvement in the countryLs balance of trade. A devaluation changes the

6

This is obtained from the first difference of H C % E M C '8NING(

),

relative prices of imports and exports in a way that encourages export growth and reduces

import volumes. 9owever, these shifts do not necessarily improve the trade balance.

The effect of a devaluation on the balance of trade '&(, in domestic currency, depends on

how the value of exports 'P

x

%( and imports 'P

m

#( respond to this devaluation. This can be

represented as

E .:

e

# P

e

% P

e

&

d

m

s

x

( ' ( '

where reflects OchangeL, e is exchange rate, P

x

is the price of exports, % is the :uantity of

exports produced and sold, P

m

is the price of imports and # is the consumption of imports.

8hanges in the value of exports or imports depend on how export and import prices change

and the effect this has on the volume of exports and imports. "oth the price and output

responses of exports and imports in turn depend on domestic and foreign price elasticities of

supply and demand for export and import products. Jsing simple algebraic manipulations a

general formula for the elasticity of response of the current account balance to the exchange

rate 'E

ca

( can be derived. This formula 'drawn from Iane# ')*.1(( is represented as

E .:

) ( > '

)

) ( > '

)

,

_

"# $#

$#

$% "%

"%

#

%

!

E E

E

E E

E

'

'

E

where E

!

is the exchange rate elasticity of the trade balance 'normalised by the value of

imports(

/

, '

%

and '

#

are the values of exports and imports, respectively, E

"%

and E

$%

are the

export elasticities of demand and supply, respectively, and E

$#

and E

"#

are the import

elasticities of supply and demand respectively. In this formula, the exchange rate elasticity

of the trade balance 'E

!

( is measured in foreign currency terms. 9owever, if trade is

balanced ''

%

E '

#

( the conditions for improving the trade balance expressed in terms of

domestic of foreign currency are e:uivalent '?indert and Aindleberger, )*-1(. This

assumption will be imposed in the remainder of the theoretical analysis. In the discussion

that follows, changes in the trade balance will be referred to in !and terms.

Gor#ing within the elasticity approach, there are four important variations that will

determine the current account response. The $mall ountry and the Prices (ixed in $eller)s

urrency cases are of direct relevance to the debate in South Africa and are briefly

discussed. The remaining two cases are presented in "ox ) and "ox 1.

ase *+ $mall country case

In the first case, the economy is modelled as a small price$ta#er in which export and import

prices are set in the international mar#et. The export demand '2

H

( and supply 'S

H

( curves

are shown in the left$hand side diagram of 4igure ), while the import demand '2

%

( and

supply 'S

%

( curves are shown in the right$hand side diagram. All prices are measured in

local currency.

"ecause of the small price$ta#er assumption, the demand curve for exports is perfectly

elastic 'E

"%

$(, indicating that the overseas mar#et can absorb any amount of output that

the small country can produce without affecting the world price. 7n the supply side, the

/

E! E 'd,&/'#-/.dr/r( where ,& is the trade balance.

))

supply of imports is perfectly elastic 'E

$#

( meaning that changes in local demand do

not influence international prices.

Substituting the demand and supply elasticities into : ,, the "!% condition for an

improvement in the trade balance becomes=

E .:

, > "# $%

#

%

! E E

'

'

E

,

This condition is satisfied so long as the import demand curve is downward sloping and the

export supply curve is upward sloping. A depreciation is thus expected to improve the trade

balance in a small price$ta#ing economy.

Figure +: Small country case

3 H

Imports xports

2 H

S H

S %L

2 % 3 %

S %

2 HL

This result can be explained using 4igure ). A devaluation shifts the demand curve for

exports upwards to 2

H

L

and the supply of imports curve upwards to S

%

L

. This is because

export and import prices measured in domestic currency rise by the full depreciation rate. In

response to the price changes, the :uantity of exports supplied increases and the :uantity of

imports demanded decreases. The value of exports increases by a greater percentage than

the depreciation as both the volume and price of exports rise. The volume of imports

declines, but this does not imply that the value of imports measured in domestic currency

declines. This depends on the elasticity of import demand. If import demand is elastic, the

domestic currency value of imports falls and the trade balance improves. If import demand

is inelastic, the domestic currency value of imports rises. 9owever, the trade balance still

improves, as the maximum the value of imports can rise by is the devaluation rate 'occurs

when import demand is perfectly inelastic(. The domestic currency value of exports,

however, increases by more than the depreciation rate.

The si&e of the impact of a devaluation depends on the elasticities of export supply and

import demand. The more elastic export supply and import demand, the greater the

improvement in the trade balance.

)1

ase /+ Prices fixed in seller)s currency

The second case reflects the well$#nown %arshall$?erner condition where a depreciation

has an ambiguous impact on the trade balance. In this case it is assumed that prices are set in

the sellerLs currency. This is an accurate representation on the import side for a small

country, as one would expect world prices to be set in foreign currencies 'E

$#

(. 7n the

export side, however, this assumption implies a perfectly elastic supply curve for exports

'E

$%

(. This condition is only li#ely to be satisfied if excess capacity exists in the

domestic economy

5

.

5

This case may be an accurate representation of the late )*-,Ls when local demand was significantly below

output, meaning that producers had spare capacity and used export mar#ets to vent this surplus capacity.

)6

!ox +

ase 0+ 1nelastic demands

The third case is shown in 4igure 1 below. 7n the left is the mar#et for exports and the right$hand

diagram illustrates the mar#et for imports. All prices are measured in local currency. In both cases

demand is perfectly inelastic 'i.e. E"% E E"# E ,( and the :uantity demanded does not respond to price

changes.

Figure -: 'nelastic demands

3

H

Imports xports

2

H

S

H

S

%L

2

%

3

%

S

%

Substituting the inelastic demands '2H E 2% E ,( into the "!% e:uation reduces the formula to=

E .: . , > < # % ! ' ' E

As this condition implies, a devaluation in the case of inelastic demands une:uivocally worsens the trade

balance. This can be shown using the diagrams in 4igure 1.

In the case of exports, a devaluation will lead to an upward shift of the demand for exports curve. In

4igure 6 above, this shift cannot be seen as the new curve is superimposed on the old curve. The vertical

distance between similar points on the two demand curves is e:ual to the percentage value of the

depreciation. 7n the import side, the depreciation will lead to an upward shift of the supply from S% to

S%L .

The domestic price and :uantity of exports stay exactly the same leaving total export revenue measured

in domestic currency unchanged. The devaluation is fully passed$through into imported prices valued in

domestic currency. Import :uantities, however, do not change as import demand is perfectly inelastic. As

a conse:uence the domestic currency value of imports rises by the same rate as the devaluation and the

trade balance moves into deficit.

Figure /: Prices fixed in seller0s currency

3 H

Imports xports

2 H

S H

S %L

2 %

3 %

S %

2 HL

Substituting the supply elasticities into : ,, the "!% condition becomes=

E .:

, ( ) ' > < "# "%

#

%

! E E

'

'

E

A devaluation can either improve or worsen the trade balance and is dependent on the

import and export demand elasticities. Assuming balanced trade, this condition can be re$

written as the well$#nown %arshall$?erner condition

E .:

) > +

"# "%

E E

,

which states that if both supply curves are perfectly elastic and the trade balance is &ero, a

devaluation of the exchange rate will improve the trade balance if the sum of the demand

elasticities is greater than one.

A devaluation shifts the demand curve for exports upwards from 2

H

to 2

H

L. The domestic

currency price does not change, implying that the pass$through of an exchange rate

depreciation to the foreign currency price of the home country exports is complete. In other

words, a ), 0 depreciation lowers the foreign currency price of home country exports by ),

0. The :uantity of export demanded rises in response to lower prices, but the si&e of the

increase depends on the elasticity of export demand 'E

"%

(. If export demand is highly

inelastic, export volumes only increase by a small amount, as does the domestic currency

value of exports. This can be shown by a very steep "x curve and a small shift to the right in

response to a devaluation.

7n the import side, domestic prices rise by the full depreciation rate. Import volumes

decline, but the change in the domestic currency value of imports depends on the elasticity

of import demand. If import demand is inelastic, the value of imports increases. Similarly, if

import demand is elastic, the domestic currency value of imports declines. A combination of

a low elasticity of export demand and a low elasticity of import demand can result in a

worsening of the trade balance in response to a devaluation. The more elastic the export and

import demand curves, the greater the improvement in the trade balance in response to a

devaluation.

)/

2.3 The J-curve

The above four scenarios present extreme views regarding the elasticities of demand and

supply in order to define the parameters of the relationship between changes in the exchange

rate and the trade balance. In reality, the demand and supply of exports and imports are

unli#ely to be perfectly elastic or inelastic. The demand and supply elasticities are a function

of a number of variables such as the si&e of the domestic economy, the availability and

number of substitutes in production and consumption, the returns to scale in production, the

availability of spare capacity and resources, etc.

The elasticity of demand and supply also differ in the short and long run, with the long$run

elasticities generally exceeding the short$run elasticities. Ghile the long$run impact of a

devaluation on the trade balance may be ade:uately reflected in the cases above, the short$

run dynamics of the trade balance as it moves towards this e:uilibrium may differ

substantially.

)5

!ox -

ase 2+ Price fixed in buyer)s currency

The final case is more of a theoretical exercise and is one in which prices are set in the buyerLs currency.

xport mar#ets face a world price set in terms of the foreign currency, while imports are priced in the local

currency. Jnder these assumptions the demand curves in both mar#ets are perfectly elastic 'E"% $ and

E"m $(, as shown in . Substituting these demand elasticities into : ,, the "!% condition for an

improvement in the trade balance becomes=

E .: ,

, )> + + Esm Esx

'm

'x

Eca

3rovided supply elasticities are not negative 'a sufficient but not necessary condition(, the trade balance will

improve in response to a devaluation.

Figure 1: Price fixed in buyer0s currency

3H

Imports xports

2H

SH

S%L

2%

3%

S%

2HL

2ifferences between the long and short$run elasticities lie behind the hypothesised @$curve

effect of a devaluation. As shown in case 1 and 6, a devaluation is more li#ely to worsen the

trade balance in countries facing a combination of inelastic export and import demand

functions and elastic export supply curves. These demand conditions are more li#ely to

occur in the short run.

%any developing economies are highly dependent on imported intermediate 'such as oil or

li:uid fuel( and capital goods used in the production process. These economies also lac# a

wide range of substitutes for these imported products implying a highly inelastic import

demand function. ven if substitutes are available, ;lags in recognition of the changed

situation, in the decision to change real variables, in delivery time, in the replacement of

inventories and materials, and in production< give rise to an inelastic demand curve in the

short run '%agee, )*+6= 6,+(. In these cases a devaluation raises the domestic currency

value of imports in the short run.

7n the export side, two factors delay the positive impact on the trade balance from a

devaluation=

). 4irstly, the rise in the export price in domestic currency terms in response to a

devaluation may be slow. 4or example, in the very short term, the domestic currency

price of goods that have already been purchased or that are in transit when the

depreciation occurs will not necessarily rise.

1. Secondly, export volumes may respond slowly to the devaluation in the short run.

As a result, a depreciation may not boost the value of exports in the short run. Together, low

elasticities of export and import demand in the short run can worsen the trade balance in

response to a devaluation. In the long run, as these curves become more elastic, the trade

balance improves.

2.4 Extensions/limitations of the elasticity approach

The elasticities approach provides a highly simplified, yet useful, framewor# for analysing

the impact of exchange rate changes on the trade balance. 4or a comprehensive analysis,

however, it is desirable to ta#e into account other factors not directly dealt with in the

elasticity approach. Some of these limitations are discussed as they feed into the empirical

analysis conducted later in this paper.

The elasticity approach is a partial euilibrium approach and does not ta#e into account

the macroeconomic effects arising from changes in prices and production in response to a

devaluation. As discussed in the absorption and monetarist approach, a depreciation gives

rise to macroeconomic effects that fre:uently undermine the positive impact of an exchange

rate devaluation on the trade balance.

7f particular importance, is the inflation impact of a devaluation. A devaluation raises the

price of imported goods utilised in the production process and also results in a substitution

in the consumption of domestic goods for imported products. "oth these demand and supply

effects place upward pressure on domestic prices. The si&e of the effect depends on the

substitutability of domestic goods for imported and exported goods 'in both consumption

and production(, the share of imports in total income, the elasticity of prices with respect to

input prices and the elasticity of factor prices with regard to domestic price levels. The

).

larger each of these factors is, the larger the response of domestic prices will be to the

increase in import prices 'Goldstein P Ahan, )*-5(. Institutional structures, such as wage

index schemes, tend to raise the sensitivity of domestic prices to import price increases

'Sachs, )*-,, :uoted in Goldstein P Ahan, )*-5(.

!ising domestic prices have three effects=

). 4irstly, they undermine the substitution of domestic for imported products arising from

the devaluation.

1. Secondly, the foreign currency price of exports rise, which negatively affects

competitiveness and the :uantity of exports demanded.

6. Thirdly, rising domestic prices lower the profitability of export production and reduce

export supply.

All these effects reduce the positive impact of a devaluation on the trade balance. Artus P

%cGuir# ')*-)(, for example, find that high domestic price feedbac# reduces the trade

balance effect by /, 0.

A second consideration is the interdependence between export production and imported

intermediate goods. Iery often exports are produced using imported capital goods. South

Africa, for example, has a highly capital intensive structure of exports 'dwards, 1,,)b(.

Growth in exports thus raises demand for imports. At the same time, rising prices of imports

reduce export competitiveness. "ecause the elasticities approach does not ta#e this

interdependence into account, the implied positive impact on the trade balance arising from

a devaluation may be exaggerated.

4inally, the elasticity approach does not ta#e into account the numerous general

euilibrium interactions arising from currency movements, such as the responsiveness of

production and consumption to relative price shifts '2ornbusch, )*+5(. The approach also

does not explain how the excess of income over expenditure that corresponds to a trade

surplus arises, as is emphasised in the absorption approach. 4inally, production responses in

export and import$competing sectors are not lin#ed into real income and expenditure effects.

4or example, rising incomes raise import demand.

2. !iscussion

This section used a simple supply and demand framewor# to analyse the various possible

outcomes of a devaluation on a countryLs trade balance. The most appropriate model for the

analysis in South Africa is li#ely to be the small country model, at least in the long run.

South African exports and imports account for approximately ,.1- 0 and ,./- 0 of world

trade, respectively 'dwards and Schoer, 1,,1(. A depreciation is thus expected to improve

the trade balance in the long run. 9owever, the short$run dynamics may differ substantially.

As shown in the %arshall$?erner relationship, inelastic import and export demand curves,

combined with elastic export supply responses, may result in an initial trade deficit in the

short run. In modelling the impact of the depreciation on the trade balance, it is important to

capture these short$run dynamics.

A further consideration is the inclusion of some of the macroeconomic lin#ages that

moderate the variation in the trade balance in response to a depreciation. 7f particular

relevance to the South African debate, is the feedbac# of a depreciation onto domestic price

inflation. Inflation tends to negate some of the positive effects of a depreciation on the trade

balance. This study attempts to incorporate the inflationary impact of a depreciation in order

)+

to provide a more comprehensive assessment of currency movements on the trade balance

than is suggested by the simple elasticities approach.

The following section reviews international and domestic empirical literature dealing with

the relationship between changes in the currency and the trade balance.

/, Empirical methodology

There are various approaches followed in estimating the impact of a currency depreciation

on the trade balance. In the direct trade balance regressions, the trade balance is regressed

directly on exchange rates and other variables '%iles, )*+*Q "hamani$7s#ooee, )*-5, )*-*Q

9imarios, )*-5Q !ose, )**,Q Shirvani and Gilbratte, )**+Q !incRn, )**-Q Aale, 1,,)(.

Ghile this approach enables a direct estimate of the relationship between the trade balance

and the exchange rate, it lac#s theoretical structure. The coefficient on the exchange rate

variable is a weighted average of the various elasticities of demand and supply of both

imports and exports. It is thus not possible to determine whether the relationship is driven

by demand or supply features. The empirical results of these analyses are ambiguous and no

consensus on the impact of the exchange rate on the current account is evident.

The 2eynesian based absorption and monetary based studies include general e:uilibrium

and econometric models. The economy$wide structural general e3uilibrium models preserve

the #ey macroeconomic identities, particularly the national income accounting identity. 4or

example, Gylfason P !adet&#i ')**)( develop a general e:uilibrium model for a range of

developing economies and find that a ), 0 devaluation improves the current account by ).5

0 on average in the sample of )1 countries studied. These models, however, are highly

sensitive to the functional forms of the consumption and production functions, as well as the

elasticities and other parameters imposed on the model.

The econometric studies estimate functions derived from the absorption and monetary

approaches. 9ossain ')***( estimates an intertemporal model in which transitory shoc#s in

income affect the current account, but not permanent shoc#s. This is consistent with the

absorption approach where the trade balance e:uals the difference between income and

absorption. 9ossain ')***( finds results consistent with the intertermporal model for the

JS, but not for @apan. 9e also finds a long$run relation between the current account and the

real exchange rate for both countries. 7ther econometric studies, such as "ahmani$7s#ooee

')*-5( and !incRn ')**-(, include production and money supply variables into their set of

independent variables explaining the trade balance. 9owever, these are largely ad hoc

additions and do not capture to the essence of the macroeconomic lin#ages emphasised in

the absorption and monetary approaches. A consistent interpretation of their coefficients is

thus not possible.

A third set of studies, the pass%through studies, estimate the pass$through of exchange rate

changes into export price changes 'in foreign currency terms( and import price changes 'in

domestic currency terms( 'Swift, )**-Q 9anninen and Toppinen, )***Q %ahdavi, 1,,,(.

These studies generally find that import prices respond relatively :uic#ly to a devaluation,

but that export prices 'in domestic currency terms( respond more slowly 'Goldstein and

Aahn, )*-5= ),-*(. This suggests that import supply elasticities are infinite, but that the

short$run elasticities of demand are low, which can give rise to the @$curve effect. In the

medium term, however, empirical evidence suggests that export prices rise by the full

depreciation rate in small or natural resource abundant economies 'such as South Africa(

)-

'Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5= ),-*(. As shown in the small country case discussed in the

theory section, an exchange depreciation thus improves the trade balance in the long run.

4inally, in the elasticity based studies export and import elasticities are estimated directly.

In the following section, the empirical methodologies used in the elasticity approach are

analysed in more detail.

3.1 The elasticities approach

This approach involves the direct estimation of the demand and supply elasticities for

exports and imports. These elasticities are then substituted into : , to determine whether

the "!% condition for an improvement in the trade balance in response to a devaluation is

satisfied.

Export demand and supply functions

The standard export model, as discussed by Goldstein and Aahn ')*-5(, can be represented

as a system of e:uations for export supply '%

s

( and export demand '%

d

(. These functions are

represented as

.

E .: %

d

4

5

6

*

Px 6

/

erate6

0

P* 6

2

7* .

*

8 5,

/

9 5,

0

9 5,

2

9 5-

%

s

4

5

6

*

Px 6

/

P 6

0

lprod 6

2

w 6

:

tariff .

*

95,

/

85,

0

95,

2

85,

:

85-

%

s

4 %

d

where 7*, P*, P, 7S Px, lprod, w, erate and tariff are real foreign income, price of foreign

domestically produced goods, domestic price, foreign income, domestic price of exports,

labour productivity, wage rates, exchange rate and tariffs, respectively. Export demand is

positively affected by foreign income '7*( and the price of competing foreign goods 'P*(,

but is negatively affected by the foreign price of domestic exports 'Px*4 Px/erate(.

Formally it is assumed that the demand function is homogenous of degree &ero in prices and

the further restriction

*

'E $

/

( 6

0

E, can be imposed.

Export supply is positively affected by Px and lprod, but negatively affected by P, w and

tariff. 7ften domestic income is also used as an exogenous variable in the export supply

function. This traditionally has a positive sign, as increased production is a proxy for non$

price improvements in competitiveness arising from increased economic activity 'Goldstein

and Aahn, )*-5(. A capacity utilisation variable can also be included to model the Ovent$for$

surplusL hypothesis. The use of capacity utilisation has been used extensively in the SA

literature '4allon and 3ereira da Silva, )**/Q Tsi#ata, )***(. The former finds a negative

coefficient while the latter finds the coefficient to be insignificantly different from &ero.

The export supply and demand e:uations solve for the two endogenous variables, Px and %,

simultaneously. This has implications for the estimation procedures followed. %ost

international 'SpitTller, )*+-Q Gilson and Ta#acs, )*+*Q 9aynes and Stone, )*-1( and

domestic '4allon and 3ereira da Silva, )**/Q "horat, )**-Q Tsi#ata, )***Q Golub and

8eglows#i, 1,,)( empirical studies estimate single export and>or import e:uations. The

estimation of a single export e:uation is only appropriate in cases where either the elasticity

.

This model is an imperfect substitutes model where imperfect substitutability between domestic and export

products enables domestic and export prices to differ from one another 'Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5(.

)*

of supply or demand is infinite.

+

Ghen the elasticity of supply is infinite 'case 1 in the

theory section(, the appropriate function to estimate is the export demand e:uation.

3roblems of simultaneity do not arise as Px is fixed and is no longer endogenous. In the

small country case where export demand is infinitely elastic 'case )(, the export supply

curve is the appropriate function to estimate. Px is again fixed, but is determined by foreign

prices.

%ore importantly, if the elasticities of supply and demand are not infinite, then the

estimation of a single e:uation with both export volumes and export prices will suffer from

simultaneous e:uation bias. In the export demand e:uation, Px is endogenous and is

correlated with the error term. This tends to bias the price elasticity of demand coefficient

downwards 'Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5(. The solution is to estimate the export supply and

demand e:uations as a system. Although a reduced form e:uation can be estimated 'solve

for Px and % in terms of the exogenous variables(, the coefficients on the relative price

variable in the export demand function is neither the export demand nor the supply

elasticity. The coefficient is a weighted average of both.

The endogeneity problem is not confined to the Px and % variables in : ,. The system

assumes that the exchange rate, domestic prices and wages are exogenous. 9owever, as

shown in many of the pass$through studies discussed earlier, domestic prices and wages are

strongly influenced by the exchange rate and foreign prices. 4urther, significant increases in

exports can cause the currency to appreciate. Ideally, the estimation techni:ues should allow

for the endogeneity of these variables.

In their review of the literature Goldstein and Aahn ')*-5( find that the long$run export

price elasticities of demand range between C).15 to C1.5. SenhadDi and %ontenegro ')**-(

analyse export demand elasticities in 56 developed and developing countries and find an

average long$run demand elasticity of C). xport demand elasticities in Africa appear to be

lower and range between C,.,/ and C1.) 'Ari&e, )*-+(. xport supply elasticities in

developed economies range between ) to / 'Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5(, but appear to be

lower in Africa where they range between , and ,.** 'Ari&e, )*-+(.

1mport demand and supply functions

Import demand functions are generally estimated under the assumption of infinite world

supply. This is appropriate in a small country case li#e SA.

-

The relevant function is of the

form=

E .: #

d

E

5

6

*

Pm 6

/

Pdom 6

0

7 6

2

tariff .

*

8 5,

/

9 5,

0

9 5,

2

8 5-

where Pm, Pdom, 7 and tariff are the import price, domestic price, real gross domestic

expenditure and tariff rates, respectively. Import demand is positively affected by rising

domestic prices and real domestic expenditure, but is negatively affected by rising import

prices. Import prices 'Pm( can rise either through a depreciation of the exchange rate or a

rise in foreign prices. As in the demand e:uation, homogeneity of import demand implies

*

6

/

E,.

+

Some of these solve for the system to obtain reduced form e:uations. It is not, however, always possible to

extract the relevant elasticities from the estimated reduced form coefficients.

-

To test this assumption we regressed the import price on the exchange rate, foreign prices and deviations of

SA G23 from trend. Ge find that exchange rate depreciations are fully passed through to import prices

measured in domestic currency.

1,

stimated long$run import demand elasticities for developed economies generally range

between C,.5 to C).5 'Table /.) in Goldstein and Aahn, )*-5= ),+*(. The short$run

elasticities are roughly half the long$run elasticities and about 5, 0 of the adDustment occurs

within a year. !esults for developing countries are less available. Ari&e ')*-+( estimates

long$run import demand elasticities between C,..+ and C).+ for a number of African

economies. SenhadDi ')**+( estimates import demand elasticities for .. developed and

developing economies and finds that the short$run elasticity is close to &ero, but the mean

long$run elasticity is e:ual to C).,+.

Together these results suggest that "!% condition is satisfied and that a devaluation will

improve the trade balance. The only exception appears to be African countries where low

elasticities were estimated.

Econometric methodology

The analysis above has highlighted a number of important issues concerning the estimation

of the supply and demand elasticities.

4irstly, the export supply and demand functions simultaneously determine the export

prices and export volumes and hence need to be estimated as a simultaneous system of

e:uations.

Secondly, other variables such as the exchange rate, wages and domestic prices are not

necessarily exogenous. The estimation techni:ue needs to allow for the endogeneity of

these variables.

A further problem associated with the estimation of the supply and demand functions is that

the data are fre:uently non$stationary in levels. The estimation of these functions in levels

may thus give rise to spurious coefficients if no cointegrating 'long$run( relationship exists.

Jsing log difference growth rates solves for the problem of non$stationarity if variables are

integrated of order one '1.*-(. 9owever, the regression results then only provide information

on the short$run dynamics around a possible long$run relationship. The estimation

techni:ues thus need to explicitly deal with the non$stationarity of data.

An appropriate methodology in these circumstances is the @ohansen %aximum ?i#elihood

procedure for multivariate cointegration analysis '@ohansen, )*--, )**1(. This approach is

appropriate as it allows for the estimation of a system of e:uations in which all variables are

endogenous '@ohansen and @uselius, )**,(. In addition, the techni:ue enables the estimation

of the long$run relationships as well as the short$run dynamics surrounding the adDustment

process 'the error correction e:uations(. The methodology is discussed in more detail in the

Appendix.

1, South African empirical evidence

There is limited research on the impact of the devaluation on the trade balance in South

Africa, with only one study, Smal ')**.(, focussing on this relationship. Fumerous studies,

however, have estimated export demand elasticities. 4ewer studies have estimated export

supply and import demand elasticities. An overview of these studies can give insight into

whether the "!% conditions for an improvement in the trade balance are satisfied. Table )

provides a summary of the various estimated elasticities for export and imports in South

Africa.

1)

Table +: South African price, income and other export elasticities

Author Price elasticity of

demand

Price elasticity

of supply

'ncome Period )omments

Export functions

"ehar and dwards '1,,6( $6 to $. ,.+. to ).6 1 to 6.5 )*+5:) to 1,,,:/ %anufacturing. Jses

I8%

dwards and Golub '1,,1( $)..1 to C1.+. ).1- to 6.)* )*+,$)**+ %anufacturing. Jses

panel data techni:ues

Golub and 8eglows#i '1,,)(

)

,.+- to $).,- ,.+. to )./. )*+,$*- Jses alternative price

variables in !!s.

Golub '1,,,(

)

$,.+- to $).6+ ,..1 to )./1 )*+,$*- Jses alternative price

variables in !!s.

$,.** to C,.-/ FS to 6..1 )*+)$*- stimated in first

differences

Faude '1,,,( S stimated in first

differences

Tsi#ata ')***( $).,* in S!

C).. in ?!

,.55 in S!

,.-) in ?!.

)*+,$*. !educed form xport

function. Jses !!

$,.- ,./5 in S! stimated in first

differences

SenhadDi and %ontenegro ')**-( $,.5 ,..5 7bs E 6/ %ulti$country study

Smal ')**.( $,.5- 'merchandise(

$)./ 'manufacturing(

$,.6) 'minerals(

,.+. to ).,/ )*-5K) to )**/K/

4allon and 3ereira de Silva

')**/(

$,./6 in S!

$,..6 in ?!

,.,1 'only for

post -5(

)*+1$-* Jsed different variables

for relative price.

"horat ')**-( 1.** for 3aper

P paper prods

).,) for 4ood,

beverage,

tobacco

Kuarterly data=

)**,.,1 C*5=)1

xport supply function

using cointegration. +

sectors.

'mport functions

Golub '1,,,( $,.,5 to ,.61 ,.*6 to ).,/ %anufacturing

SenhadDi ')**+( $).,/ in ?!

$,.// in S!

,..- 7bs E 6/ %ulti$country study

Smal ')**.( $,.-5 )./+ )*-5K) to )**/K/ %erchandise imports

excluding oil

Aahn ')*-+( $).)5 1.). %anufacturing

Fotes= ?! is long run, S! is short run.

xport demand elasticities have been estimated using numerous different specifications and

econometric techni:ues. The estimated long$run export price elasticities of demand range

from C,./ to C., with lower estimates in the short run.

All estimates, apart from "ehar and dwards '1,,6(, either impose the assumption of

infinite export supply, or estimate a reduced form of the export function. As discussed in the

empirical methodology section, this induces simultaneous e:uation bias into the estimate. A

contribution of this study is that it estimates the supply and demand functions as a set of

simultaneous e:uations.

The approach of estimating export demand functions is also inconsistent with the view that

South Africa is a small country facing an infinite demand for exports. A further problem

with most of these estimates is that their relative price variable 'the real effective exchange

rate( is constructed using consumer prices, producer prices or unit labour costs as the price

variables, rather than export prices. These alternative prices include non$traded products and

do not necessarily reflect changes in the relative price of South African exports measured in

the foreign currency.

This is a severe limitation as it is not clear whether the estimated price elasticities are

demand or supply elasticities. 4or example, the studies of Golub '1,,,(, Golub and

11

8eglows#i '1,,)( and dwards and Golub '1,,1( use a !! constructed from unit labour

costs, i.e.

E .:

f

$!

e;L

;L

<EE<

where ;L is the unit labour cost and e

is the exchange rate. The subscripts $! and f refer to

South Africa and foreign countries, respectively. In these studies, a depreciation of the

currency and>or a decline in J?8 in South Africa is interpreted as an improvement in export

competitiveness, i.e. there is full pass$through into the price of exports measured in foreign

currency. xport growth responds, as it also suggested by the estimated coefficients which

range between C,.+- to C1.+..

9owever, in a small country export prices move in conDunction with the exchange rate 'as

shown in case ) of the theory section(, i.e. dPx/P E de/e. In the event of a depreciation, the

price of exports increases by the amount of the depreciation, but unit labour costs do not as

they are a non$traded factor. d.;L

$!

/Px-, which is e:uivalent to d.;L

$!

/e- in a small

country in the long run, falls implying profitability of export production has risen. xports

respond, not because foreign demand increases, but because export supply increases. Similar

arguments can be made for studies using !! calculated with 83I or 33I indices, as these

indices also contain prices of non$traded products. The estimated price elasticities of

demand in many of the South African studies may really be supply elasticities.

"ehar and dwards '1,,6( utilise multivariate cointegration techni:ues to estimate export

demand elasticities for South African manufacturing exports. The estimated long$run

elasticities range between C6 and C.. These elasticities are very high suggesting that South

Africa approximates a small country. A preferred specification of the export demand

function is one in which the export price is the normalised variable 'see later(. This would

enable a direct testing of the small country hypothesis.

4ewer studies have attempted to estimate export supply elasticities and import demand

elasticities. "horat ')**-( estimates supply elasticities for + manufacturing sub$sectors. The

results are largely poor with only / of the sectors showing significant coefficients of the

correct sign. 4urther, many of the coefficients on the domestic price variable are negative,

which is inconsistent with theory. These problems possibly relate to the very short time

period ')**, C )**5( over which the analysis was conducted. This period is inade:uate to

estimate long$run relationships. Supply elasticities for manufacturing have also been

estimated by "ehar and dwards '1,,6( using :uarterly data between )*+5 and 1,,,. The

estimated long$run price elasticities of supply range between ,.+. and ).6. The export price,

however, is incorrectly measured in foreign currency rather than in domestic currency.

stimated long$run import demand elasticities range between C,.-5 and $).)5. I SenhadDi

')**+( estimates the short$run import demand elasticity to be C,.//. Thus, in the short run

the domestic currency value of imports appears to rise in response to a devaluation, but

declines slightly or remains constant in the long run.

Together the import demand and export elasticities suggest that a depreciation improves the

trade balance in South Africa. Imposing the small country assumption and substituting the

average long$run import demand '$).,)( and export supply ').)/( elasticities into : ,,

16

yields a long$run exchange rate elasticity of the trade balance 'E

!

( e:ual to 1.)5.

*

A ) 0

depreciation thus improves the trade balance by 1.)5 0 'of the value of imports( in the long$

run. The average short run elasticities of import demand and export supply are C,.// and

,.-6, respectively. This yields a trade balance elasticity e:ual to ).1+. Thus, the short$run

impact of a depreciation on the trade balance is less than the long$run impact, but both

appear positive.

The positive impact on the trade balance is also the conclusion drawn by Smal ')**.(.

9owever, the si&e of the improvement depends on how domestic prices and wages respond

to the depreciation. Jsing an econometric macro$economic model, Smal ')**.( shows that

a depreciation without restrictive fiscal and monetary policy can result in a substantial

increase in inflation. This negatively affects income and employment relative to a scenario

where wage growth is moderated and government expenditure fell in real terms. Strangely,

the current account balance declined relative to the inflation simulation.

3, !ac&ground data analysis

This section provides a cursory overview of South African export and import trends since

the early )*+,s. A primary obDective is to obtain some preliminary insights into the

relationship between export performance and competitiveness vis$B$vis international

producers and vis$B$vis production for the domestic mar#et. Increased competitiveness vis$

B$vis international producers influences exports according to the export demand function.

Improved profitability in the production of exports relative to domestic goods positively

affects export supply.

A clear understanding of these relationships is essential for the initial specification of the

export demand and supply functions that are to be estimated. As discussed in the

methodology section, if firms are found to be a Oprice$ta#erL in international mar#ets, i.e.

export and import prices are fixed in foreign currency prices, domestic export prices rise by

the full depreciation of the currency and exports increase because domestic production

thereof has become relatively more profitable. In this case it is appropriate to estimate the

export supply function while assuming an infinite demand for exports.

Alternatively, if domestic exporters are found to have some pricing power, through product

specialisation and>or a large share in world exports, a depreciation lowers the foreign

currency price of South African exports and the :uantity of exports demanded increases.

The extent of the increase depends on the elasticity of demand. In these cases it is

appropriate to estimate to both supply and demand curves 'assuming export supply is not