WES Nov 2008 ARTC 250 - Rev - 4

Diunggah oleh

aldo123456789Deskripsi Asli:

Judul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

WES Nov 2008 ARTC 250 - Rev - 4

Diunggah oleh

aldo123456789Hak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1

Puttingtheprocessbackin:Rethinkingservicesector

skill

Ian Hampson

The University of New South Wales

Anne Junor

The University of New South Wales

The final, definitive version of this paper has been published in Work,

Employment and Society, 24(3) September 2010: 526-545,

doi:10.1177/0950017010371664

by SAGE Publications Ltd./SAGE Publications, Inc., All rights reserved.

URL: http://wes.sagepub.com

ABSTRACT

Service skill definitions have been over-extended, by equating compliance with skill,

and under-developed, by not recognising service jobs invisible social and

organisational aspects. Existing approaches to determining service skill levels draw

on occupational qualifications and capacity for labour market closure, on knowledge

worker/knowledgeable emotion worker dichotomies, and on the conceptual conflation

of labour process deskilling, unskilled jobs and unskilled workers. The theoretical and

empirical basis for a new framework identifying hitherto under-specified work

process skills is outlined. This framework allows recognition of the integrated use of

awareness-shaping, relationship-shaping and coordination skills, at different levels of

experience-based complexity, derived from reflexive learning and collective problem-

solving in the workplace. Political struggles over the use of combinations and levels

of these skills of experience may result either in jobs designed to reduce autonomy,

or in improved skill recognition and development, enhancing equity and career paths.

KEY WORDS

articulation work/ emotional labour/ service work/ skill/ work process knowledge/

workplace learning/ equity

2

Introduction

The growth of service sector employment has problematised the meaning of skill

(Hilton, 2008). Employers have overextended the concept to include required

employee attributes and attitudes (Keep and Mayhew, 1999), defining skill to reflect

their preferences for compliant workers (Lafer, 2004). However, employers also say

they need human capacities for independent problem-solving, self-direction,

collaboration in self-managing teams, ethical judgment, and the capacity for

negotiation and empathetic interaction qualities that sit uneasily with

submissiveness. When employers recruit on the basis of maturity or experience,

for what life or work skills may these be proxies? When care-workers expostulate that

they earn no more after ten years than on entry, or than their offspring earn at a

supermarket checkout (Richardson and Martin, 2004: 26-7), are they perhaps

expressing a conviction that their work involves a range of skills, based on experience

acquired in the process of working? Such real practical expertise is often under-

recognised and unrewarded (Gatta et al., 2007), and one reason for this is lack of a

vocabulary to register certain tacit skills and the levels at which they are applied. Pay

and employment equity are advanced only through political contestation, but an

adequate skill vocabulary may be part of such contestation (Hall and Reed, 2007).

One of the future scenarios for the service sector is the development of an hourglass,

or barbell shaped distribution of skills. From this perspective, a relatively small

minority of knowledge workers will have thinking skills but many more will rely

on social competencies now defined as low level (Autor, 2007; Thompson, 2007:

89). Nevertheless, the skills required in service occupations, whether defined as low,

middle or high level, need further examination. Some see these skills as natural

attributes, that anyone would want to have (Autor, 2007, in Hilton, 2008: 13); as

mundane accomplishments in plentiful supply (Attewell, 1990: 423; Payne, 2009:

355: Lloyd and Payne, 2009: 12). Others argue that many social competences are

forms of skilled emotion management, that not all workers will have (Bolton, 2005).

It is argued here that a multiplicity of forms of service sector work may be performed

at varying levels of proficiency, and that these require capacities that include, but

3

extend beyond, the emotional. These include awareness of contexts and

consequences, capacity for moral and aesthetic judgment, rapid contextual evaluation,

intercultural competence, and organisational ability. These human capacities are

skills, and the article explicates an attempt to develop an empirically grounded

taxonomy, designed to allow identification of their use at a range of levels.

From 2006 to 2008 the authors were part of a team funded by the New Zealand (NZ)

Department of Labour Pay and Employment Equity Unit, working to develop new

techniques for identifying service skills (New Zealand Government, 2009). The skills

framework that arose from this project, outlined here, has been used successfully in

public and community sector trials, to help pinpoint the exercise of hitherto under-

specified capabilities, bringing a new rigour to the identification of levels of expertise

in their workplace application. The framework is not an exhaustive list of service

skills. Rather it provides a conceptual basis for investigating the use, in specific work

contexts, of three broad sets of skills that are central to service sector work. It also

provides a way of identifying five learning stages through which these skills are

developed by reflective practice, both individual and collective. While this conceptual

taxonomy is now starting to be used in practice in parts of the NZ community care

sector to help define under-specified job content and worker capabilities, the focus

here is on its theoretical implications for debates over service sector skill.

First the emerging range of service industries and occupations is examined, and it is

noted that employers report some service skills to be in short supply. Next the article

overviews the concepts on which the research drew, based on labour process theory

(LPT), interactionist insights and a theory of workplace learning. The third section

describes the empirical project, explaining the methods of gathering and analysing

data from a cross-section of service jobholders, cross-referencing theory and data

analysis. The final section outlines the resulting taxonomy of process skills,

illustrating how it aids the naming of more specific skills at a range of levels. The

conclusion explores the potential contribution of the findings to LPT.

Who are Service Workers?

4

Across UK industry groupings, in March 2009, 81 per cent of employees were located

in service jobs. The largest grouping was administration, education and health (33 per

cent), followed by distribution, hotels and restaurants (20 per cent), and banking,

finance and insurance (16 per cent). NZ, where we undertook our empirical research,

had a very similar industry distribution (Office for National Statistics, 2009; Statistics

NZ, 2007).

Occupational evidence gives only qualified support to the thesis that service skills are

distributed hourglass-fashion. In the UK in March 2009, 29 per cent of employees

overall were assigned to managerial or professional occupations and another 15 per

cent were defined as associate professional or technical employees. A middle 22 per

cent were evenly divided between clerical/administrative staff and skilled trades. The

lower end (34 per cent) comprised four groupings: personal service workers (mainly

health and child care) (9 per cent), sales and customer service workers (including call

centre staff) (7 per cent), process, plant and machine operatives (7%), and elementary

employee groups including hospitality workers, hospital porters, cleaners and security

staff (12 per cent) (Office for National Statistics, 2009). NZ had a roughly similar

occupational distribution (Statistics NZ, 2007).

This distribution was hourglass-shaped only if we assume that all health and child

care workers were low-skilled. True, a 2008 Statistics NZ survey of over 25,000

organisations indicated that, at the point of recruitment, skill shortages were greatest

in trade, professional and managerial occupations. But it also indicated that, owing to

lack of experience half of all existing employees did not have the skills required to

do their jobs well: and that skills in customer service, team working and oral

communication were most lacking (Statistics NZ, 2008). These findings provide

support for our thesis, that entry-level qualifications may not certify the work process

skills required for effective work performance, and that such skills are acquired only

through workplace practice. The shortage of these skills questions their designation as

mundane accomplishments in plentiful supply. Applying the analogy of Brown et al.

(2001: 36), they are not plug and play capacities that workers bring to the job and

immediately switch on and use. Rather, they are like a flat pack: they need to be

built up and integrated with the requirements of their surrounds. Conceptualising the

skills of experience in this way helps explain why apparently abundant low level

5

skills in the community require workplace learning and in some cases formal training,

before they can be applied at the required level of expertise. Paid community care

work is a case in point.

Theorising service skills

Insights from Labour Process Theory

The fundamental LPT problematic is the quest to manage commodified but

indeterminate labour power to secure valorisation and safeguard accumulation

(Thompson, 1989: 241-243). Thus the indeterminacy of labour power is the problem,

control is the solution, and deskilling is the most fully realised form of control,

resulting in subordination, and involving erosion of both autonomy and task

complexity. LPT has been extended to commodified work that is not low-skilled:

professional, associate professional, public sector and even managerial work

(Ackroyd, 2009). Whilst not defined as low-skill in terms of qualifications, and less

likely to suffer loss of task complexity, these occupations are formally subordinated to

other managerial control and work intensification systems such as responsible

autonomy (Friedman, 1990), high performance work systems (Danford, 2003) and

individual performance target-setting. For these reasons, macro-analysis suggests that

task complexity and worker autonomy may be trending in opposite directions

(Felstead et al., 2004).

Hochschild famously extended the loss of employee autonomy to the managerial

regulation of feeling within service work. She saw emotional labour as no small part

of what trainers train, and supervisors supervise (1993: xii) thus defining it as both

learned and political behaviour. She extended her analysis beyond airline cabins, debt

collection, department stores and hospitality, to health, welfare and education. But

subordination is a tendency never fully achieved, and Korczynski (2002) and Bolton

(2005) in particular explore areas of contradiction within emotional labour. Bolton, in

describing flight attendants and call center workers as skilled emotion managers,

emphasises both moral agency and adroit management of self, others and situations.

Thus across a range of occupational levels, micro-analysis of the intangible cognitive

6

and affective elements of the service labour process reveals that the relationship

between autonomy and complexity is not clear-cut.

It is perhaps the parallels with technologically-controlled factory production that have

made areas of retail and telemarketing a focus of LPT analyses of service work,

although these are a minority of service jobs, and entry to them requires

uncharacteristically low levels of educational qualifications and life/work experience.

Even so, much customer service call centre work undoubtedly demands uncodified

skills of experience. Thus Taylor and Bain (2004: 17) argue that call centre work is

repetitive, routinised, and dominated by short cycle times but at times it

requires deeper skills (2004: 28). However, a vocabulary to name these skills is

missing. Callaghan and Thompson (2002: 248) similarly see some call centre workers

as ...active and skilled emotion managers, whilst allocating them to low level

status. These writers propose the concept of knowledgeability

1

to encapsulate how

interactive service workers display

consciousness of their social skills and an awareness of when and how to deploy these. It is

possible to see this personal awareness as a kind of tacit knowledge, where workers develop

an understanding of themselves that allows them to consciously use their emotions to

influence the quality of the interactive service sector product (Thompson et al., 2001: 937-8).

The concept of knowledgeability needs elaboration, lest it become a carpet

sweeper term for capacities, the basis of whose differentiation from skill is

incompletely defined.

The historical strand within LPT has tended to define skill as employees capacity to

retain control of facets of the labour process. In particular there has been a focus on

unions power to turn skill recognition, based on entry qualifications, into

occupational closure, thus gaining a defence against role fragmentation and skill

dilution (Thompson, 1989: 46-53). It is within this analytical tradition that Payne

(2009) challenges the claim that emotion work is skilled. He warns against the over-

extension of skill claims, satirising the view that we are all skilled now and

critiquing attempts to define non-technical activities, however complex, as skilled

(also see Lloyd and Payne, 2009).

7

Yet skill cannot be equated simply with labour market strategies based on

occupational closure. Workplace learning theory points to the importance of the

ongoing development of the situated, tacit and often collective capacity to carry out

work processes (Lave and Wenger, 1991). For strategic reasons, employers may

recognise the development of uncredentialled skills for some employees, through

internal job ladders, and refuse such recognition to others (Osterman, 1987). Workers,

however, may be able to claim skill through legal or industrial campaigns. The

managerial tool of job evaluation has been used with some success to gain skill

recognition in feminised jobs (Hall and Reed, 2007; Steinberg, 1998). In Australia,

the industrial relations system, which allows collective skill assessments based on

work value claims, is a potential pay equity vehicle. The majority report of a recent

parliamentary inquiry recommends a system for pursuing job or occupational

revaluation through claims that skill and responsibility have been historically

undervalued on a gender basis (Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia, 2009).

Many submissions to this inquiry argued the undervaluing of service skills, linked to

the invisibility of womens skills (eg. p.7); the perception of womens skills as

natural attributes or social skills, rather than industrial or workplace skills (eg p.55);

and failure to specify skills relating to caring, communications and personal

interaction (eg p.57).

The rest of this article outlines the stages of an empirical study we undertook for the

NZ Department of Labour, precisely to identify and classify such service skills,

starting with the theoretical derivation of our research and interview questions.

Theorising service skill content

One starting point was Boltons (2005) innovative combination of LPT with

interactionist concepts, particularly those of Goffman, to analyse work processes

involving skilled emotion management. As Bolton and Houlihan (2005) point out,

service work cannot be fully routinised, since work on other people involves ethical

juggling, and subtle judgment of effects. Another interactionist, Strauss, provides an

extensive typology of the content of sentimental (emotion) work, as well as a sense

of how it is interwoven with various other forms of work in time (Strauss et al. 1985:

133-139). Based on studies of hospital work, these researchers identify: negotiative,

8

composure, rectification, awareness-context, and dirty work (the latter involving

ethical conflicts, as well as emptying bedpans), which embrace both emotional and

cognitive domains. Awareness context work refers to the shaping of ones own

awareness and that of others. For example, staff withholding information which they

believe will be difficult for a person to handle are involved in a subtle interplay of

personal ethics, will and identity, as well as negotiating the compulsion of political

and economic structures.

Central to the analysis was the Straussian notion of work as a process, with workers

collectively and individually coordinating disparate components of work into a

smooth flow. Strauss et al. (1985) referred to this process as articulation work, a

supra type of work, involving the coordination of tasks in time, in individual lines

and collective arcs and trajectories of work (Strauss, 1985: 2, 8). Articulation

work skills are the second order or reflexive skills of integrating lower levels of

skill, and interweaving lines of work. They include situational awareness, relationship

management and interpersonal negotiation (Strauss, et al., 1985: 87). Extending this

analysis, service work in health, education, community services and administration

also required linking activities (follow-through, follow-up), and continuity of

awareness in the management, establishment, maintenance and termination of

relationships that extend well beyond the one-off transactions on which analysts of

interactive frontline work seem to focus. Coordination and ethical juggling come

together in managing the conflicting demands of clock time and clients process

time (Davies, 1994): time management goes beyond scheduling, to include the

accommodation of diverse temporalities.

Beyond content analyses of service skill, the research sought a way of

conceptualising skill levels. Mainstream occupational and job analysis techniques,

which like LPT use the dimensions of autonomy-control and substantive

complexity proved to be of limited help in identifying service skills at different levels

(Spenner, 1990). By taking the task as their basic unit, they overlook the skills

required to link tasks up into processes (Forfs, 2007: 24). Moreover, the formal

vocational qualifications that define occupational skill levels tend to anatomise task

skills, with less attention to dynamic work process skills (Boreham, 2002).

9

Theorising service skill levels

This shift of focus to integrated work processes has implications for LPT. The

managerial routinisation of complex processes may rely on workers being sufficiently

skilled to work automatically, incorporating contingency and linking together

activities into smooth sequences. If so, there is no automatic fit between deskilling

processes, unskilled jobs and minimally-qualified workers. LPT, in focusing on

contests over autonomy and complexity, has paid rather little attention to skill

development, and articulation work theory does not help in theorising skill levels,

beyond its concept of supra work (Strauss, 1985: 2, 8). To identify levels of

proficiency in the exercise of tacit service skills, is to begin to move beyond the

skilled/unskilled dichotomy toward a concept of workplace skill formation as the

staged assimilation of practical learning, resulting in expertise achieved over time.

Individually-focused learning theory describes how, after repeated practice, a novice

acquires the proficiency to carry out a process (like keyboarding) automatically,

releasing cognitive resources for other activity (like composition) (Dreyfus and

Dreyfus, 1986; Shuell, 1990). In time, the worker can apply experience at a level of

automaticity, and is cognitively freed to focus on solving new problems. Activity

theory (Leontev, 1978; Sawchuk, 2006) similarly describes how novices build a base

of experience through iterations of practice, reflection and problem-solving. Thus our

first three skill levels were derived: familiarisation, automatic fluency, and proficient

problem solving. To take account of the collective basis of workplace learning,

however, the analysis was deepened and extended to a fourth learning level of

creative solution sharing, where experienced workers informally pool their work

process knowledge. The knowledge, and the collective learning process, may be tacit

or explicit, involving both verbal, and less explicit and more fleeting, information

exchange. Learning takes place, knowledge is transmitted, and identity is shaped,

through steadily increasing participation in communities of interaction/practice

(Sandberg, 2000; Brown and Duguid, 1991). This analysis moves beyond the Anglo-

liberal view of competence as something that is always individual (Boreham 2004). It

is congruent with the theory of work process knowledge (Boreham et al, 2002),

which reinforces the importance of situational and process awareness as foundational

skills and informed our empirical study of service skills.

10

Empirical evidence

Methodological basis

Workplace interviews, conducted in the latter part of 2006, focused on service

employment in the NZ core public service, health and education sectors, which

accounted for approximately 15 per cent of the total workforce or a little over 20 per

cent of the service sector. Occupationally, jobs in the NZ core public service

workforce are 50 per cent managerial, professional and associate professional, 34 per

cent clerical and administrative, and 13 per cent community and personal service

based (State Services Commission, 2007). Relative to the total service sector, the

research sample was therefore skewed to more highly qualified occupational levels. In

2008-2009 further research tested the wider relevance of the taxonomy derived from

such jobs, through validation studies in the community care sector. The addition of

more low-status jobs tended to confirm the relevance of the approach to

approximately one-third of service jobs those in non-profit sectors.

Occupational evidence gives only qualified support to the thesis that service

skills are distributed hourglass-fashion. In the UK in March 2009, 29 percent

of employees overall were assigned to managerial or professional

occupations and another 15 percent were defined as associate professional or

technical employees. A middle 22 percent were evenly divided between clerical/

administrative staff and skilled trades. The lower end (29%) comprised

three groupings: personal service workers (mainly health and child care) (9%),

sales and customer service workers (including call centre staff) (8%), and elementary

employee groups including hospitality workers, hospital porters,

cleaners and security staff (12%) (Office for National Statistics, 2009). NZ had

a roughly similar occupational distribution (Statistics NZ, 2007).

It cannot be assumed that all 29 percent in the three lowest-level occupations

(for example health and child care workers) were low-skilled workers

The original study took the form of semi-structured interviews, averaging 90 minutes

in duration, with workers in 57 different jobs, ranging in level from administrative

assistant to senior policy adviser; from education support worker to senior lecturer;

and from patient receptionist and care assistant to director of nursing. A quarter of the

jobs were in predominantly male occupations, a third were in gender mixed

occupations and a little over half were in jobs that were over 70 per cent female. The

interviews produced completed questionnaires and 1,600 pages of transcripts

11

containing discussions of critical incidents and workplace learning trajectories. To

this data set we added 94 position descriptions and job evaluation reports. Iterative

coding, based on the NVivo software program and the Strauss-Corbin (1998)

abstraction technique, was used to group and condense similar work activities, from

which we drew a matrix of irreducible under-specified work process skill elements

and learning stages. Collaborative discussion of many iterations of this coding finally

narrowed it down to nine skill elements grouped into the three skill sets of shaping

awareness, interacting and relating, and coordination. The final condensation of 150

activity examples from which these skills were abstracted was found to be readily

organised into the four skill levels outlined above, plus a fifth level, drawn mainly

from accounts by official and unofficial experts and leaders, of how they actively

shaped solutions, embedding them in work systems.

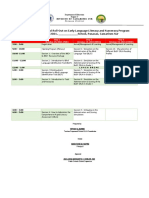

Table 1 sets out the resulting framework of skill sets, elements and levels. Each skill

is an individual capability for participating in a collective work activity. We turned

the 150 activities, classified according to the skill elements and skill levels they

illustrate, into a checklist that could be used to map job skill requirements and

workers skills. In 2008 we tested various uses of this framework as an aid to

position description writing, selection, individual development planning, job

sequencing and career pathing, in a two day workshop with public, education and

health sector managers, and then with 100 workshop participants from community

sector organisations. In 2009, one-on-one trials with community sector workers have

shown the effectiveness of the framework in building integrated individual profiles of

skills and developmental targets. In the rest of this article, we illustrate how this

taxonomy can be used to analyse the skills underpinning work activity and processes,

concentrating on front-line reception work, low-paid support roles, and several

middle level jobs such as IT support and casework.

TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE

Applying a new service skills framework

12

The analysis develops two argument. Firstly work involving responsibility for the care

or development of others, or for the negotiated maintenance of work systems, is likely

to involve some complexity in the integrated use of non-mundane, and often tacit,

skills of awareness-management, inter-relating and coordination. Second, autonomous

proficiency in deploying these skills develops with experience. As a result, further

theorisation is needed of the relationship between two types of skills: those acquired

through formal learning and certified in qualifications, and those gained through

collective workplace learning.

Exemplifying the use of work process skills in low level personal service occupations,

an Occupational Therapy Assistant (OTA) worked in a job classified at a lower level

even than hospital-based Personal Care Assistants. She commented:

Were undervalued I think by the hospital system [I]ts not recognised, the skills or the

values The care assistants have got formal training; the occupational therapy assistants

havent got that paperwork behind us. (OTA, NZ, 2006)

After two years nursing training, this informant turned to OTA work for its more

holistic approach: [Y]ou can work with families not just dealing with the injury

or the condition. The job had three components: daily reception and administrative

work, handling phone calls and mail relating to clients, families and equipment

suppliers; and unpacking, cataloguing and assembling rehabilitation equipment: This

required contextual awareness skills (So yes, you have to know what the equipment

is and what its about), as well as an understanding of the work of the rehabilitation

team (the OTA minuted regular cross-disciplinary team meetings).

The second aspect of the work involved both daily rounds of the hospital ward,

providing ADL (assistance with daily living) and frequent home visits, assembling

and adjusting equipment and coaching in its use. Teamwork was involved (Youre

working with a physiotherapist, youre working with the speech therapist) and work

with clients required finely-tuned communication and boundary-management skills:

13

Learning how to encourage people to do things for themselves without being condescending.

My communication skills have certainly picked up The hardest thing I had to learn was let

the patient do it for themselves rather than you do it. (OTA, NZ, 2006)

The third aspect of the job was to accompany therapists one day a week, on house

calls in a regional community, providing safety backup through contingency

management. The job involved the negotiation of both subordination and autonomy:

I think it is something you learn as you go...Theres a lot of independence: you have to make

decisions [but] there is a line there and you have to refer to a therapist Especially the

younger therapists, I feel because I'm a little bit older, youre imparting your knowledge to them

because they havent had the experience. Youve got to be very diplomatic, if that makes sense?

(OTA, NZ, 2006)

To integrate the jobs three lines of work, and fold them into the hospitals ongoing

arc of work, required coordinating and negotiating skills:

Time management was one of my hardest ones and its something Ive been working on with the

team leader. . [B]ecause I cover different areas, I'm learning to say no, and work in with the

other therapists. [They] ask you to do different things, because theres only a certain amount of

time that you have in the day and being able to say No, I cant do that now, but I can do it at

such and such a time. So youre planning all the time and then being able to adjust your day

because theyre little emergencies and things that pop up all the time, so youve got to fit those

in. (OTA, NZ, 2006)

This example illustrates the integrated use of many of the elements identified in Table

1 management of the awareness of self, others, situations and impacts; negotiation of

boundaries, communication across class and culture, and integrated maintenance of

work flows.

Similarly low in occupational status and paid close to the minimum wage are an

estimated 20,000 NZ school support staff working in roles such as teacher aides,

administrators, and resource co-coordinators. Special Education Support Workers

(ESWs) are assigned, often on a one-to-one basis, to help children with disabilities

integrate and learn in preschool and school classrooms. Low-level post-school

qualifications are increasingly being gained, often after years in the job. The tacit

14

skills involved in this work can be gleaned from accounts of apparently mundane

incidents such as the following (relating to a three-year old Mori child with spina

bifida):

Id been playing around the theme of this is a spoon, this is a drawerThen its clean-

up timeI said, Could you put it in the drawer? and she did it. Its just a little thing but she

did it. She understood So those sorts of thing are the little steps they make all the time.

(Special Education Support Worker, NZ, 2006)

This example illustrates the use of verbal and non-verbal communication cues, and a

fine-tuned awareness of the significance of incidents within longer-term changes in

the child. A detailed developmental program was discussed daily with teachers and

parents and regularly within a multi-disciplinary care team. The skills required

included a subtle awareness of reactions and impacts; interpretative non-verbal

communication, and activity-sequencing and interweaving. Vigilant to small warning

signs, the ESW routinely managed problems ranging from constant risk of falls to

dealing with epileptic seizures without disturbing other children or the flow of activity

in an open-plan classroom. The work required skills in managing up and advocacy

at the level of problem-solving: the ESW has previously needed to draw on strategic

negotiating skills to persuade a teacher to abandon her enthusiasm for a new

approach, because of its detrimental effects on one child. She had picked up on the

emotional exhaustion of a mother of autistic twins, and used silent empathetic

listening to avert the risk of family trauma. Another ESW, responsible for up to six

older children in a special needs centre, had trouble naming the non-verbal

communication skills she used in quietly encouraging school-refusers into the

classroom, blocking out the screaming and maintaining a reassuring firmness. She

described how through experience she had learned to maintain a stable working

environment with children likely to respond to any frustration by biting and kicking,

and the wisdom needed to manage grief at the deaths of frail severely-disabled

children. Such skills of insight into self and others that underpinned this work of

social integration are unlikely to be in plentiful supply off the street.

The tacit skills of experience identified in Table 1 were also seen as important in jobs

requiring tertiary-level occupational qualifications:

15

[H]aving the qualification got me the job, but now Im doing stuff that the qualification didnt

show me ... You actually need someone with great listening skills, and a qualifications not

going to give you that. You do have to have a certain amount of knowledge, and the tertiary

qualification will give you that, but it also asks for skills that a qualification is not going to

give you. (Information Technology Helpdesk Officer, Polytechnic, NZ, 2006)

This example raises the question of whether the tacit experiential skills identified in

Table 1 were similar at different occupational levels. Certainly, beginning workers in

jobs at different occupational levels all had to start by using Level 1 familiarisation

skills. For the IT support workers, this involved contextual awareness and boundary

management skills:

Territory would be a big issue ... And thats almost like that political context as well.I have

a couple of what I consider to be almost mentors, and Ill pick their brains. Yes. Finding

someone who knows. It can take a while sometimes, cant it?

Yes, especially when you talk to the wrong people.

MisinformationIts also asking the right person, and that is a trick of the trade as well. (Two

IT Support staff, Polytechnic, NZ, 2006)

The reflective and self-reflexive aspects of assessing information and people in

context entitle these capabilities to be labelled skills. Such skills may be exercised at

varying levels within jobs at all qualification levels. We use the example of

administrative assistant/reception work, to illustrate the progression from skill Level 1

(familiarisation) to Level 2 (automatic fluency) and Level 3 (problem-solving). The

example is based on work in a rehabilitation outpatients clinic, involving the follow-

up of discharged patients, administration of pain-management programs, and

coordination with welfare and accident compensation agencies, as well as

management of client queues. This front-line worker built her awareness of contexts

and consequences, and used the interpersonal skills of boundary-setting and reading

people to enable her to maintain a smooth workflow. She quickly learned to manage

her own awareness of situations and people, as importunate pain-sufferers tried to

gain immediate access to doctors:

They quite often ring you and try to seek a lot of information out of you, which I wasnt

prepared for. And because I hadnt worked in a medical environment before, I wasnt quite

16

sure of what those boundaries were. So.... I had to go back and check with people that I was

offering the right level of information what the limitations were. (Administrative

Assistant, NZ, 2006)

It proved necessary to build up a lay understanding of medical terms, which our

informant did by maintaining a notebook. This ambiguously authorized knowledge

was necessitated by the unofficial triage element of the work, one of whose main

goals involved the use of coordinating skills to ensure that the doctors workflow

proceeded without interruption. Self-awareness and boundary-management skills

were required at the problem-solving level (level 3):

youve got to try and second guess how important these things are, before you can interact

And youre building up your medical knowledge about how important something is. And

not getting so emotionally involved and realising theres a limit to what you can and cant do.

(Administrative Assistant, NZ, 2006)

This example illustrates the cognitive element in emotional labour: [i]ts sort of

stepping back from the situation and having a look at the big picture. It also

illustrates why such skills may be in short supply in the workplace: only by

combining contextual understanding with job-specific learning can evaluative,

interpersonal, and coordinating skills become translated into effective practice and

problem-solving.

An interview with a Health Care Assistant (HCA) provided insights into the interplay of

experiential and formal learning in care work, and suggested the advantage of qualification

structures that provide for a two-way movement between reflection and practical experience.

This informant commented that, through experience, she was better able than many

new grad nurses to read the signs if somebodys going to die.

And on more than a few occasions, they have been going to die, and Ive been able to let the

nurse know and theyve been able to call the family to get them in. (HCA, NZ, 2006)

She identified the tacit skills required for two-way communication with stroke

patients: And when youve got something rightyou can understand what theyre

saying back to you. She and her colleagues had collectively developed techniques for

providing behavioural cues to a developmentally-delayed fifty-year old patient, using

17

the patients doll to model what was required. Such collective development of these

skills (classified at level 4 in Table 1) was often informal. Indeed, highly-qualified

professionals might learn from care assistants in the cross-disciplinary team meetings

that the hospital has systematised. Such practical communication skills, gained

through trial and error, are becoming codified: for example there is now standard

training available on communicating with Alzheimers sufferers, and on de-escalating

aggression.

Our final example comes from the higher-level frontline job of caseworker, engaged

by a public sector benefits agency to work with people judged to need assistance with

personal and social issues if they were to make effective use of employment services

and welfare assistance. Normal caseworker qualifications were a generalist degree or

relevant life experience. Case management involved the building of ongoing

relationships through a combination of telephone and face-to-face interviews.

Caseworkers found themselves rapidly progressing through the experiential skill

levels in Table 1:

technologically we get five weeks training in the systems and applications. Ive been here

20 months and I still dont know how to use them all They cannot train you on how to use

all the systems entirely; that is impossible. Just the enormity of those systems and their

relationships. (Caseworker, NZ, 2006)

Nevertheless, the work required very rapid progression to the use of problem-solving

skills (Level 3):

From day one, you are expected to use discretion. It is the job essentially. You are to make

the decisions. You learn by trial and error Of course after a period of time, theres a

familiarity, even though every day there will be a circumstance we havent run into before

(Caseworker, NZ, 2006)

Unrecognised skill requirements meant that caseworkers tended to create informal

teams to learn from each other:

You identify very quickly who the people are that you work with, that are prepared to be

involved in your learning process, and who isnt. (Caseworker, NZ, 2006)

18

Awareness shaping and coordinating skills were thus being used at the level of

creative solution-sharing (Level 4): So its on the job training; reliant on your team

mates. The Level 5 skills of experience, relating to formal ways of bringing about

system change (Table 1) were more accessible to people in managerial positions, who

also had higher-level formal qualifications.

The focus here has been on establishing the existence of under-specified skills of

experience in lower-level jobs evidence that is currently being used to revisit such

jobs value and career path potential. Trials in May and June 2009 highlighted the

utility of our framework in providing a vocabulary for establishing skills required to

work in community organisations - skills whose scope extended to system-building

(NZ Department of Labour, 2009).

Conclusion: New Contradictions of Agency and Control

Skill needs some rethinking, putting an analysis of process back into conceptions of

work. Concepts such as communication, problem-solving or teamwork represent work

activities and processes, not skills as such, although the skills enable such work

processes to take place. Skill is the human capacity, individual or collective, to

perform work processes, and it entails learning. A way has been outlined of

conceptualising three sets of invisible, hard-to-define-service sector skills those

involved in awareness-shaping, interaction and relationship management, and

coordination. These skill sets underpin to varying degrees the demands of service jobs

that require the management of emotion, self and time.. Five skill levels mark

increasing levels of participation in work processes, resulting in workplace learning

through shared practice and problem-solving.

Whilst the descriptors above may call forth an impression of itemisation, even

fragmentation, each descriptor registers not a task, but an aspect of a process. As

Figure 1 suggests, the taxonomy provides a menu for the identification of nine skill

elements, exercised together at varying levels, each contributing to the ability to

combine discrete tasks into ongoing work processes. The integrated control of a work

19

activity is ultimately in the hands (or the soul) of the person performing it, expressing

workers individual and collective identity, itself partly embedded in the workplace.

Claiming skill is therefore, in part, claiming identity, and is a recognition of

agency.

There are tensions in this analysis which are interesting as well as troubling. First,

individual service sector workers should have their skills and competencies

recognised, developed, rewarded and valued. This requires fine grained apprehension

of work processes. However, making invisible work process visible is a two edged

sword. A more accurate understanding of what employees are really doing can

facilitate employer control. On balance, the advantages of recognising hidden skills

may outweigh this danger, although justice in remuneration requires more than

visibility. Recognition of skill has two aspects: seeing the skill, as well as giving its

possessor respect and dignity and paying for it. Second, although skill recognition

and remuneration are focussed on the individual, higher levels of individual

competence were found to be tied up with collective learning and practice. This

finding returns the analysis to the work process, the collective worker and, ultimately,

the question of identity.

Our analysis of skill development highlights the hidden injuries of routinisation. With

growing experience, workers may encounter an ever-widening gap between restrictive

job design and skills that are required yet thwarted, exercised covertly but under-

recognised. In attempting to clarify some of the theoretical issues that still bedevil the

concept of skill, the analysis has sought to put the process (both of work and of

learning) back into labour process concepts of service sector skill.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Editor and the anonymous referees for their comments on an

earlier draft of this paper.

We particularly thank Philippa Hall, Director, Pay and Employment Equity Unit, NZ

Department of Labour, for guidance and project facilitation, Drs Alison Barnes and

20

Meg Smith (University of Western Sydney); Gemma Piercy (University of Waikato);

Dr Robyn Ogle (Deakin University); and Dr Peter Ewer (Labour Market Alternatives,

Australia). Validation work was undertaken by Janice Burns (Top Drawer

Consultants, NZ), Kerry Davies (NZ Public Service Association,), Dr Celia Briar

(Human Rights Commission, NZ), and Conor Twyford (Workplace Wellbeing, NZ).

Notes

1

A concept first used in a manufacturing context, cf Thompson 1989: xii, 82, 92

References

Ackroyd, S. (2009) Labor Process Theory a Normal Science, Employee

Responsibilities and Rights Journal, Online First Edition, July.

Attewell, P. (1990) What is Skill?, Work and Occupations 17 (4): 422-448.

Autor, D. (2007) Technological change and job polarization: Implications for skill

demand and wage inequality. Presentation at the National Academies

Workshop on Research Evidence Related to Future Skill Demands URL

(Consulted 23 July, 2009]

http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Future_Skill_Demands_Presentations.ht

ml.

Boreham, N. (2002) Work Process Knowledge in Technological and Organisational

Development, in N. Boreham, R. Samuray and M. Fischer (eds) Work Process

Knowledge, pp. 1-14. London: Routledge.

Boreham, N., Samuray, R. and Fischer, M. (eds) (2002) Work Process Knowledge.

London: Routledge.

Boreham, N. (2004) A Theory of Collective Competence: Challenging the Neo-

Liberal Individualisation of Performance at Work, British Journal of

Educational Studies 52(1):5-17.

Bolton, S. (2005) Emotion Management in the Workplace. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Bolton, S. and Houlihan, M. (2005) The (Mis)representation of Customer Service,

Work, Employment and Society 19(4): 685-703.

21

Brown, J. and Duguid, P. (1991) Organisational Learning and Communities of

Practice: Towards a Unified View of Working, Learning and Innovation,

Organisation Science 2(1): 40-57.

Brown, P., Green, A. and Lauder, H. (2001) High Skills: Globalization,

Competitiveness and Skill Formation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Callaghan, G. and Thompson. P. (2002) We Recruit Attitude: The Selection and

Shaping of Routine Call Centre Labour, Journal of Management Studies 39(2):

233-254.

Danford, A. (2003) Workers, unions and the high performance workplace, Work,

Employment and Society, 17(3): 569-573.

Davies, K. (1994) The tensions between process time and clock time in care-work

Time and Society, 3(3): 277-303.

Dreyfus, H. and Dreyfus, S. (1986) Mind over Machine: The Power of Human

Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Felstead, A., Gallie, D.and Green, F. (2004) Job Complexity and Task Discretion:

Tracking the Direction of Skills at Work in Britain. In C. Warhurst, I. Grugulis.

and E. Keep (eds) The Skills that Matter, pp. 148-169. Basingstoke: Palgrave

Macmillan.

Forfs Expert Group on Future Skills Needs Secretariat (2007) The Changing Nature

of Generic Skills. Dublin: Forfs (National Policy and Advisory Board for

Enterprise, Trade, Science, Technology and Innovation).

Friedman, A. (1990) Managerial Strategies, Activities, Techniques and Technology,

Towards a Complex Theory of the Labour Process, in D. Knights and H.

Willmott (eds) Labour Process Theory , pp. 177-209, London: Macmillan.

Gatta, M., Boushey, H. and Appelbaum, E. (2007) High-Touch and Here-To-Stay:

Future Skills Demands in Low Wage Service Occupations. Paper

commissioned for a workshop organized by the National Academies Center for

Education on Research Evidence Related to Future Skills Demands Washington,

DC, May 31-June 1, URL (consulted 27 July, 2007)

http://www7.nationalacademies.org/cfe/Future_Skill_Demands_Mary_Gatta_Pa

per.pdf.

Hall, P. and Reed, R. (2007). Pay Equity Strategies: Notes from New Zealand and

New South Wales Labour and Industry 18(2): 33-50.

22

Hilton, M. (2008) Research on Future Skill Demands: A Workshop Summary. Centre

for Education, Division of Behavioural and Social Sciences and Education,

National Research Council of the National Academies. Washington DC:

National Academies Press.

Hochschild, A. (1993) Preface, in S. Fineman (ed.) Emotion in Organisations, pp.

ix-xiii, London: Sage.

Keep, E. and Mayhew, K.(1999) The Assessment: Knowledge, Skills, and

Competitiveness, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15(1): 115.

Korczynski, M. (2002) Human Resource Management in Service Work. London:

Palgrave.

Lafer, G. (2004) What is Skill? Training for Discipline in the Low-Wage Labour

Market, in C. Warhurst, I/ Grugulis, I. and E. Keep (eds.) The Skills that

Matter, pp. 109-127, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lave, J and Wenger, E. (1990) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral

Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leontev, A. (1978) Activity, Consciousness, and Personality. Englewood Cliffs:

Prentice Hall.

Lloyd, C. and J. Payne (2009) Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing:

interrogating new skill concepts in service work the view from two UK call

centres, Work, Employment and Society, 23(4):1-18

NZDL (New Zealand Department of Labour) (2009) Spotlight: A Skills Recognition

Tool, Wellington: Department of Labour Te Tari Mahi.

Office for National Statistics (2009) Labour Force Survey Historical Quarterly

Supplement - Calendar Quarters, March , URL (consulted 16 July 2010):

http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_labour.

Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia (2009) Making it Fair: Pay Equity and

Associated Issues Related to Increasing Female Participation in the Workforce,

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Employment and Workplace

Relations, Canberra, November.

Payne, J. (2009) Emotional Labour and Skill: A Reappraisal, Gender, Work and

Organisation 16(3): 348-367.

23

Richardson, S. and Martin, B. (2004) The Care of Older Australians: A Picture of the

Residential Aged Care Workforce. Adelaide: National Institute of Labour

Studies, Flinders University.

Sandberg, J. (2000) Understanding Human Competence at Work: An Interpretative

Approach, The Academy of Management Journal 31(1): 9-25.

Sawchuk, P. (2006) Use-value and the Re-Thinking of Skills, Learning and the

Labour Process, Journal of Industrial Relations 48(4): 238-262.

Shuell, T. (1990) Phases of Meaningful Learning, Review of Educational Research

60(4): 531-541.

Spenner, K. (1990) Skill: Meanings, Methods and Measures, Work and Occupations

17(4): 399-421.

State Services Commission (2007) Human Resource Capability Survey of Public

Service Departments as at 30 June 2007, Wellington: State Services

Commission.

Statistics NZ (2007). Labour Market Statistics 2007, Table 1, URL (consulted 12

July, 2008) http://www.stats.govt.nz.

Statistics NZ (2008) Business Operation Survey, URL (consulted 18 July, 2009)

http://www.stats.govt.nz/buiness-operations-survey-2008-tables.htm.

Steinberg, R. (1990) Social construction of skill: Gender, power and comparable

worth Work and Occupations, 17(4): 449-482.

Strauss, A. (1985) Work and the Division of Labour, The Sociological Quarterly

26(1): 1-19.

Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1998) Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and

Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2

nd

ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage

Publications.

Strauss, A., Fagerhaugh, S., Suczek, B., and Wiener, C. (1985) The Social

Organization of Medical Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, P. and Bain, P. (2004) Call Centre Offshoring to India: The Revenge of

History?, Labour and Industry 14(3): 15-38.

Thompson, P. (1989) The Nature of Work: An Introduction to Debates on the Labour

Process. London: MacMillan.

Thompson, P. (2007) Making Capital: Strategic Dilemmas for HRM, in Bolton, S.

and Houlihan, M. (eds.) Searching for the Human in Human Resource

24

Management: Theory, Practice and Workplace Connections, pp. 81-99, London:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Thompson, P., Warhurst, C. and Callaghan, G. (2001) Ignorant Theory and

Knowledgeable Workers: Knowledge, Skills and Competencies in Interactive

Service Work, Journal of Management Studies 38(7): 923-942.

25

Table 1 Framework for indentifying under-specified work process skills and skill levels

SKI LL SETS AND THEI R ELEMENTS

The SKI LLS OF:

SKI LL LEVELS

Breadth or depth of skill required for increasing levels of participation

Level 1.

Familiaris

-ation

Level 2.

Automatic

fluency

Level 3.

Proficient

problem-

solving

Level 4.

Creative

solution

sharing

Level 5.

Expert

system

shaping

Build

experience

through

practice &

reflection

Apply experience

independently &

automatically

Use automatic

proficiency while

solving new

problems

Help create new

approaches

through shared

solutions

Embed

expertise in a

system

Examples of activities using these skills

A. Shaping awareness:

Capacity to develop, focus and shape your own and

others awareness, by

A1 Sensing contexts or situations

A2 Monitoring and guiding reactions

A3 Judging impacts

Be alert to

jobs

contexts &

impacts of

your

reactions

Automatically

pick up on small

warning signs

Handle conflicting

levels of

awareness and

disclosure needs

Exchange

situational

updates and

new solutions

with colleagues

Use an

understanding

of systems in

order to

influence them

B. I nteracting and relating:

Capacity to negotiate inter-personal, organisational and

inter-cultural relationships by

B1 Negotiating boundaries

B2 Communicating verbally and nonverbally

B3 Connecting across cultures

Learn to

interact

respectfully

and easily

across

cultures

Gain cooperation

of people

outside your

authority

Pleasantly deflect

distracting

requests whilst

picking up subtle

signs of real need

Give

unobtrusive

guidance in

unequal power

situations

Crystallise

views of

diverse group

with apt or

memorable

language

C. Coordinating:

Capacity to organise your own work, link it into the overall

workflow and deal with obstacles and disruptions, by

C1 Sequencing and combining activities

C2 Interweaving your activities with others

C3 Maintaining and restoring work-flow

Learn to sort

and

sequence

own activities

& work in

with others

Automatically

address what

needs fixing up

or following

through

Maintain

workflow whilst

problem-solving,

assessing the

urgency of

competing issues

Build informal

information

exchange or

contingency

support network

Contribute to

sustainable

work systems

by coordinating

backup plans

26

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Business Studies in Action H SC 6 eDokumen597 halamanBusiness Studies in Action H SC 6 eDEK Games100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- Demo (Inverse of One-to-One Functions)Dokumen3 halamanDemo (Inverse of One-to-One Functions)April Joy LascuñaBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Structural SyllabusDokumen5 halamanStructural SyllabusTugba Nayir100% (1)

- CN38 En0194 ChinaDokumen1 halamanCN38 En0194 Chinasam yadavBelum ada peringkat

- CIE iGCSE English Language - Formal LetterDokumen1 halamanCIE iGCSE English Language - Formal Lettersophmurr0% (2)

- Football Injury: Literature: A ReviewDokumen11 halamanFootball Injury: Literature: A Reviewaldo123456789Belum ada peringkat

- Identifying Optimal Overload and Taper in Elite Swimmers Over TimeDokumen11 halamanIdentifying Optimal Overload and Taper in Elite Swimmers Over Timealdo123456789Belum ada peringkat

- Research Report and BibliographyDokumen101 halamanResearch Report and Bibliographyaldo123456789Belum ada peringkat

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDokumen19 halamanNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptaldo123456789Belum ada peringkat

- WSO - Info July JuneDokumen8 halamanWSO - Info July JuneVõ Đặng TrọngBelum ada peringkat

- Small Talk in NegotiationsDokumen4 halamanSmall Talk in NegotiationsGabrielle Jones100% (1)

- LPDokumen4 halamanLPCharm PosadasBelum ada peringkat

- 1.tender Creation - PublishDokumen190 halaman1.tender Creation - PublishTanuja Sawant 50Belum ada peringkat

- Blended Learning 6 ModelsDokumen4 halamanBlended Learning 6 ModelsRod Dumala GarciaBelum ada peringkat

- Activity6 RaqueñoDokumen2 halamanActivity6 RaqueñoAlyzza RaquenoBelum ada peringkat

- Jessica Simpson ResumeDokumen3 halamanJessica Simpson Resumeapi-272859385Belum ada peringkat

- Group DiscussionDokumen14 halamanGroup DiscussionBettappa patilBelum ada peringkat

- Class 02 (Esp500)Dokumen20 halamanClass 02 (Esp500)Pato SaavedraBelum ada peringkat

- Daily Lesson LOG: Sumilil National High School - Bagumbayan Annex 8 Jessan N. Lendio Science JULY 2-5, 1:00-2:00 PM 1Dokumen3 halamanDaily Lesson LOG: Sumilil National High School - Bagumbayan Annex 8 Jessan N. Lendio Science JULY 2-5, 1:00-2:00 PM 1Jessan NeriBelum ada peringkat

- Lesson Plan (Listening and Speaking)Dokumen4 halamanLesson Plan (Listening and Speaking)Jojo1234100% (1)

- Au t2 e 3536 Years 36 Persuasive Devices Powerpoint English Ver 2Dokumen20 halamanAu t2 e 3536 Years 36 Persuasive Devices Powerpoint English Ver 2Yasmine SamirBelum ada peringkat

- Process of CommunicationDokumen11 halamanProcess of CommunicationEdhel CabalquintoBelum ada peringkat

- Naushad ResumeDokumen4 halamanNaushad ResumeMd NaushadBelum ada peringkat

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDokumen2 halamanDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesMEDARDO OBRA100% (1)

- Narrative ReportDokumen5 halamanNarrative ReportMelissa RegondolaBelum ada peringkat

- Objective: Books of MythsDokumen4 halamanObjective: Books of MythsAnne CayabanBelum ada peringkat

- Activity DesignDokumen2 halamanActivity DesignEvan Siano Bautista100% (1)

- Action Plan Training MatrixDokumen5 halamanAction Plan Training Matrixlyra mae maravillaBelum ada peringkat

- Small Group Lesson PlanDokumen3 halamanSmall Group Lesson Planapi-427436497Belum ada peringkat

- Yes We Can 1Dokumen144 halamanYes We Can 1MARÍA EVANGELINA FLORES DÍAZ100% (2)

- Speaking Naturally Tillitt Bruce Newton Bruder MaryDokumen128 halamanSpeaking Naturally Tillitt Bruce Newton Bruder MaryamegmhBelum ada peringkat

- Cambridge Assessment International Education: Arabic 9680/51 October/November 2018Dokumen6 halamanCambridge Assessment International Education: Arabic 9680/51 October/November 2018Alaska DavisBelum ada peringkat

- S&Ais3000 PDFDokumen150 halamanS&Ais3000 PDFNarcis PatrascuBelum ada peringkat

- Bunny Cakes Pre-Student Teaching Lesson 2Dokumen6 halamanBunny Cakes Pre-Student Teaching Lesson 2api-582642472Belum ada peringkat