Children's Media Culture - Skripta

Diunggah oleh

kso870 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

58 tayangan18 halamanChildren's Media Culture - Skripta

Hak Cipta

© © All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniChildren's Media Culture - Skripta

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

0 penilaian0% menganggap dokumen ini bermanfaat (0 suara)

58 tayangan18 halamanChildren's Media Culture - Skripta

Diunggah oleh

kso87Children's Media Culture - Skripta

Hak Cipta:

© All Rights Reserved

Format Tersedia

Unduh sebagai DOC, PDF, TXT atau baca online dari Scribd

Anda di halaman 1dari 18

CHILDREN'S MEDIA CULTURE IN ENGLISH

1. Why can a 4-year old eco!e "r#$h%ened o" E.T.&

A four year old children can become frightened of E.T. because of his strange physical

appearence. Children bring less real-world knowledge and experience to the media

environment. They have the lack of real-world knowledge and that can make children more

willing to believe the information they receive.

'. Wha% are yo(n$ ch#ldren) older ch#ldren and adole*cen%* "r#$h%ened o" +h#le +a%ch#n$

T,& G#-e e.a!/le* "or each o" %he*e $ro(/*.

A) ounger children!"-# years)- they can be frightened by disorted characters! E.T.) and

animals !$ambi)

$) %lder children- they can be frightened by disorted characters and in&ouries ! all tipes of

horor movies)

C) Adolesens- They can be frightened by in&ouries and blood

0. Ho+ #* %he !ed#a en-#ro!en% %oday d#""eren% "ro! %he one "aced y o(r /aren%* and

$rand/aren%*&

Terms such as digital television, gangsta rap and World Wide Web did not even exist '" or ("

years ago. The advent of cable and satellite television has dramatically increased the number

of channels available in most homes today. )igital cable is multiplying this capacity. *any

homes are e+uiped with C) players, )-) players, modems and digital cameras. The T-

screen once provided a way to watch broadcast television and now is being used for online

shopping, video-on demand...

)igital technology today gives more realistic images and sounds and media is used far more

than in the past.

4. Wha% #* a 1%h#rd-/er*on-e"ec%2&

*ost adults believe that they personally are not affected much by the mass media. .n a well-

documented phenomenon called the /third-person-efect0 people routinely report that others

are more strongly influenced by the mass media than they themselves are. Adults percieve

that the younger the person is, the stronger the effect of media will be. .nterestingly, even

children endorse a kind of third-person effect, claiming that only /little kids0 imitate what

they see on T-.

3. Wha% are 4!ed#a /an#c*5& E.a!/le6

1anics that gain steam any time a public crisis occurs such as the massacre at Columbine 2igh

3chool or any time a new and unknown form of media technology is developed. *edia

features material that children are simply not yet ready to confront.

7. Wha% #* a 4!a$#c-+#ndo+ /er*/ec%#-e5 and +ho doe* #% a""ec%&

1

.t is literal interpretation which reflects the idea that young children naively assume that

television provides a view of the real world. $y around age 4, the young child begins to

appreciate the representational nature of television but still tends to assume that anything that

looks real is real.

8. Who are hea-y %ele-#*#on -#e+er*&

Those who watch T- for more than 5 and a half hours a day.

9. Wha% do hea-y %ele-#*#on -#e+er* /erce#-e ao(% %he#r chance* o" e#n$ #n-ol-ed #n

-#olence and ao(% %r(*%#n$ o%her*& Why&

The research of 6erbner and his associates has shown that heavy television viewers perceive

the chances of being involved in violence as greater than light viewers do. They are also more

prone to believe that others cannot be trusted.

:. Wha% *y!/%o!* doe* %oo !(ch %ele-#*#on +a%ch#n$ /ro-o;e&

As the number of hours of television viewing per day increased, so did the prevalence of

symptoms of psychological trauma such as anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress.

3imilarly, the amount of children7s television viewing !especially television viewing at

bedtime) and having a television in their own bedroom were significantly related to sleep

disturbances. Although these survey data cannot rule out the alternative explanation that

children experiencing trauma or sleep difficulties are more likely to turn to television for

distraction , they are consistent with the conclusion that the exposure to frightening and

disturbing images on television contributes to a child7s level of stress and anxiety.

1<. E.a!/le* o" %he #!/ac% o" +#%ne**#n$ *cary !ed#a e-en%.

An experimental study explored the impact of witnessing scary media events on the

subse+uent behavioral choices of children in kindergarten through fifth grade. .n this

experiment, exposure to dramati8ed depiction of a deadly house fire or a drowning increased

children7s self own lives. *ore important, these fictional depictions affected the children7s

preferences for normal, everyday activities that were related to the tragedies they had &ust

witnessed9 children who had seen a movie depicting a drowning expressed less willingness to

go canoeing than other children did: those who had seen the program about a house fire were

less eager to build a fire in a fireplace. Although the duration of such effects was not

measured, the effects were undoubtedly short-lived, especially because debriefings were

employed and safety guidelines were taught so that no child would experience long-term

distress.

11. Are %ho*e "ear* *hor% or lon$-la*%#n$& = E./la#n.

- anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress, sleep disturbances - if T- is in children;s

bedrooms

-exposure to frightening and disturbing images on tv contributes to a child;s level of stress and

anxiety.

An experimental study explored the impact of witnessing scary media events on the

subse+uent behavioral choices of children in kindergarten through fifth grade. .n this

2

experiment, exposure to dramati8ed depictions of a deadly house fire or a drowning increased

children;s fear. !self < own lives=)*ore important, these fictional deciption affected the

children;s preferences for normal, everyday activities that were related to the tragedies that

had &ust witnessed9 children who had seen a movie depicting a drowning expressed less

willingness to go canoeing that other children did: those who had seen the program about the

house fire were less eager to build a fire in a fireplace. Although the duration of such effects

was not measured, the effects were undoubtly *hor%-l#-ed, especially because debriefings

were employed and safety guidelines were taught so that no child would experience long-term

distress !Cantor and %mdahl, >???)

There is growing evidence, in fact that the fear induced by mass media exposure is often

intense a long- lasting, with something debilitating effects.

Adults < motion picture

4@A of the respondents !>?A of the total sample) had experience for a% lea*% %+o day*, a

;;significant stress reaction;; as a result of watching a movie. As for the effects reported, both

studies revealed variety of intense reactions. .n study, B>A reported a generalised fear of fire

floating anxiety after viewing, 4BA reported what they called ;;wild imagination;;, '?A

reported a specific fear !sharks, power tools, spiders) and more than '"A reported a variety of

sleep disturbances, including fear of sleeping alone, nightmares, insomnia, or needing to sleep

with the lights on.

*oreover, the third of those who reported having been frightened said that the fear effects had

lasted !ore %han a year.

3ome people who felt acute and disabling anxiety states enduring several days to several

weeks or more !some neccessitating hospitali8ation) are said to have been precipitated by the

viewing of horror movies such as The Exorcist, .nvasion of the $ody 3natchers and

6hostwatch.

1'. Wha% #* +#ld #!a$#na%#on&

Chen person is afraid of monster under the bad, or someone sneaking up on you.

10. Wha% #* %he ene"#% o" r#*;-%a;#n$ and *ee#n$ *cary #!a$e*&

There have been some arguments, particularly in the psychoanalitic literature that scary

images in the media reduce rather than increase anxieties by allowing children to confront

their real fears in a safe content. There are some limited cicumstances, however, when a

frightening media depiction might be effective in alleviating anxiety. This anxiety reducing

effect appears to occur only when the story induces no more than a mild level of fear and

when the outcome of the story reveals that the danger can be effectively counteracted.

14. Do ch#ldren eco!e le** a"ra#d o" *ee#n$ *cary #!a$e* +#%h a$e& E./la#n.

As children mature cognitively, some things become less likely to disturb them, whereas other

things become more upsetting. This generali8ation is consistent with developmental

differences in children;s fears in general. Children from approximately ( to @ years of age are

frightened primarly by animals, the dark, supernatural beingsand anything that looks strange

and moves suddenly. The fears of ? to >' years old;s are more often related to personal in&ury

and physical destruction and the in&ury and death of family members. Adolescent continue

3

having these fears but they also have social fears.. A random survey of parents of children in

kindergarten, second, fourth and sixth grade showed that fear produced by fantasy programs

decreased as the child;s grade increased. -alkenburg also found a decrese in fright responses

to fantasy content between the ages of # and >'. As children mature they become frightened

by media depictions involving increasingly abstract concepts.

13. E./la#n "an%a*y -* real#%y a* "ear #nd(cer*>.

As children mature they become more responsive to realistic dangers and less responsive to

fantastic dangers depicted in the media. -ery young children are more likely to fear things

that are not real !such as monsters).

- Dear produced by fantasy programs decreased as the child7s grade increased whereas

fear induced by news stories increased with age.

17. E./la#n 5re*/on*e* %o a*%rac% %hrea%*>.

As children mature they become frightened by media depictions involving increasingly

abstract concepts. Children7s response to the television movie EThe )ay AfterF led to the

prediction that the youngest children would be the least affected by it. .n a random telephone

survey of parents conducted the night after the broadcast of this movie, children under >'

were reportedly much less disturbed by the film then were teenagers, and parents were the

most disturbed. As they mature children are increasingly responsive to abstract as opposed to

concrete aspects of frightening media. As the child7s age increased, the more abstract,

conceptual aspects of the coverage !e.g. the possibility of the conflict spreading) were cited by

parents as the most disturbing.

18. Wha% are no% co$n#%#-e and co$n#%#-e *%ra%e$#e* o" deal#n$ +#%h "ear& E.a!/le*6

G%T-C%6G.T.-E 3THATE6.E3- are those that do not involve the proccesing of verbal

information and appear to be relativetly automatic. The pprocess of visual desensiti8ation or

gradual exposure to threatening images in a non-threatining context.

EIA*1JE3-Kholding into a blanket or a toyK-Kgeting something to eat or drinkK !during

movie)

C%6G.T.-E 3THATE6.E3- involve verbal information that is used to cast the threat in a

different light. EIA*1JE-Ktell yourself it;s not realK -Kthis probable will not happen to youK

19.Who $e% !ore "r#$h%ened re$ard#n$ %he $ender&

This is a common stereotype that girl are more easly frightened than boys, and indeed females

in general are more emotional than males. the observed general difference seem to be partially

attributable to sociali8ation pressures on girls to express their fears and on boys to inhabit

them.

1:. Wha% can /aren%* do %o red(ce ch#ldren?* "ear /ro-o;ed y !ed#a&

>) The amount of time children spend watching television should be limited.

') 1arents should be especially concerned about childrenLs viewing before bedtime and

should not allow children to have a television in their bedroom.

4

() 1arents sholud become aware of the content of the television programs and movies their

children see, by watching programs and movies beforehand, by ac+uiring whatever

information is available from television and movie ratings, by reading reviews and

program descriptions, and by watching programs with their children.

4) 1arents should monitor their own television viewing and reali8e that children may be

affected by programming that their parents watch even if they do not seem to be paying

attention.

5) 1arents should consider various available blocking technologies, such as the --chip,

which is now re+uired in all new television with a diagonal screen si8e of >( inches or

larger.

B) An awareness of the developmental trends in the stimuli that frighten children can help

parents make wiser choices about programming thet their children may safely view.

#) An understanding of the types of coping strategies for dealing with media-induced fears

can help parents reduce their childrenLs fears once they have been aroused.

'<. Wha% %y/e* o" *e.(al con%en% e.#*%&

Types of sexual content9

a) at scene level9 the type of sexual behavior !e.g., physical flirting, passionate kissing), the

type of talk about sex !e.g., comment about own or otherLs sexual actions or desires, talk

about previous sex, talk about sex crimes, talk toward sex): the degree of explicitness

!provokative dress, disrobing, discreet nudity, nudity): the age and relationship of the

characters involved in intercourse: and the presence or absence of alcohol andMor drugs.

b) at the pogram level9 sexual patience !i.e., abstaining from or waiting to have sex for moral,

emotional, or health-related reasons), sexual precaution !i.e., the use of or talk about

preventive measures to reduce the risk of sexulally transmitted diseases-3T)s), and sexual

risks andMor negative conse+uences !i.e., unwanted pregnancy, 3T)s, A.)3).

'1. De*cr#e %he a!o(n% and na%(re o" *e.(al con%en% #n /r#!e %#!e.

>) The amount of general sexual content in prime time has increased dramatically over time.

Dor example, 4(A of all shows aired during the Kfamily hourK in >?#B contained some form

of sexual content.

') Talk about sex is much more fre+uent in prime time than is sexual behavior !verbal

references to sex occurred twice as fre+uently in prime time as sexual behavior did).

() The physical act of intercourse is rarely portrayed explicitly on prime time. Chen it

appears, it is more verbally reffered to or implied than depicted !prikazan) on-screen.

4) Sexual behaviors usually occur between characters who are not married. 2eterosexual

intercourse !verbal, implied, physical) and erotic touching were more likely to be shown

between unmarried characters than married ones.

5) The possible life-threatening !2.-MA.)3) or life-altering !pregnancy) consequences of

sexual intercourses are seldom discussed or presented.

5

''. De*cr#e %he a!o(n% and na%(re o" *e.(al con%en% #n *oa/ o/era*) !(*#c -#deo* an

!o-#e*.

SO! O!"#S

.n terms of sheer prevalence, soaps are filled with sexual content. @5A of soap operas on T-

featured some form of sexual content and almost half showed sexual behavior. The most

fre+uent types of sexual acts in soap operas are depictions !prikazi) involving unmarried

couples and long kisses. $ehaviors involving prostitution, petting and homosexuality are

depicted infre+uently in this genre. The amount of sexual acts per hour increased (5A

between >?@5 and >??4. 3exual behaviors were almost three times as likely.

$%S&' (&)"OS

3tudies reveal that music videos feature some form of sexual content. Dor exapmle, $axter

found that B"A of the music videos in their sample featured sexual content. 3herman and

)ominick found that #BA of >BB concept videos analy8ed featured some form of sexual

content, at a rate of 4.#@ sex acts per video. Context or way in which sexual content is

featured in music videos may contribute to negative effects. *ore than ( fourths !@>A) of

music videos featuring violence also contain sexual content, which heightens the risk of

desensiti8ation !desenzibilizaci*a). Comen are more likely to be shown wearing provocative

clothing, engaging in implicitly sexual behavior, and being targets of aggressive, explicit or

implicit sexual acts.

$O(&"S

%ne content analysis of popular H-rated films found an average og >#.5 sex acts and ?.@

instances of nudity per film. Demales were 4 times more likely to be shown nude than were

males. The most fre+uent type of sexual activity in H-rated films was intercourse among

unmarried characters. %f particular concern is adolescents; exposure to films featuring the

mixture of sex and violence.

'0. Doe* -e+#n$ *e.(al con%en% ha-e an #!/ac%&E./la#n.

( conclusions from researches9

teenagers are learning facts about sex from television and other media. These findings

suggest that many teenagers may be turning to the mass media because they do not get

enough information about seks at home or in school.

teenagersLattitudes toward coital behavior are influenced by exposure to sexual

content on television. -iewing scenes of pre- or extra-marital sex may be having a

negative effect on young viewersLattitudes and beliefs about early initiation of

intercourse.

Exposure to the mixture of seks and violence may be desensiti8ing young viewers.

3uch depictions may also be teaching male adolescents myths about rape and about

the victimes of sexual assault.

.t is also possible that exposure to seks on T- leads to increased acceptance of and

desire to engage in premarital intercourse

6

'4.Wha% are concern* ao(% %he ne% re$ard#n$ *e.(al con%en%&

%f greatest concern is sexual content or exploitation targeting children. 3uch material ranges

from photographs to the Get e+uvalent of /phone sex0 . Adult websites that feature /hard

core0 sexual depictions are also of e+ual concern.

2ighly sophisticated search engines will allow acces to almost any sexual content to almost

everyone who knows how to use it.

3imilarity of web address codes also may lead to unwanted content. Dor example

www.whitehouse.com instead www.whitehouse.gov.

There are still no finished researches about this area but it is believed that informaton about

this will soon be available.

'3. Wha% *ho(ld %he /aren%* do %o con"ron% %he e""ec%* o" *e.(al con%en% #n %he !ed#a&

Dor parents is recommended the following9 $e aware of the potential risks associated with

viewing televised portrays of sex ! e.g. learning, cultivation). Consider the context of sexual

depictions in making viewing decisions for children. Consider a child;s developmental level

when making viewing decisions.

'7. Wha% #* %he !a@or d#""erence %oday co!/ared %o %ho*e concern* #n %he /a*% re$ard#n$

%echnolo$y&

The ma&or difference today, compared with those concerns in the past, is a technology that

children and adolescents are often more sophisticated in and knowledgeable about than their

parents. such resistance to the technology, combined with a limited knowledge base, will

make solutions to potential problems like easy access to sexual images even more difficult.

'8. Wha% are %he co!/onen%* o" %he In%erne%& E./la#n %he!.

.nternet is simply a vast group of computer networks linked around the world and it has a

number of various components familiar to most of us that have the ability to deliver sexual

massages9

E-mail for electronic communication in which phone numbers and photography can be

exchanged

$ulletin board system for posting the information

Chat rooms that can be used for real-time posting and conversation !ability to change

personal information)

The Corld Cide Ceb, which combines visual, sounds and text together in a manner

that allows linkages across many sites that are related to particular topics !can be

related to sex, pornographyN)

7

'9. Wha% are %he !a@or concern* ao(% %he (*e o" In%erne%& Elaora%e.

The greatest concern is sexual content or exploitation targeting children. 3uch material ranges

from photos to the net e+uivalent of Ophone sex7 sometimes with a live video connection.

3ending sexual information over e-mail or posting on bulletin boards by those targeting

children has been a long time issue. E+ual concerns are adult web sites that feature Ohard core7

sexual depictions. Another concern is adolescents or children who simply click their mouse

and indicate they are of age and enter the adult site. There is a strong need for research this

area-usage , content and effects of .nternet access among children.

':. Wha% are *o!e o" %he *ol(%#on* %o In%erne% concern*&

There are three ma&or approaches. The first is government regulation restricting the content.

Cithin the Pnited 3tates, the Dirst Amendment protects offensive speech from censorship,

including sexually explicit materials. The P.3. courts have struck down most content

restrictions on books, maga8ines and films. There are exceptions such as QobscenityE, child

pornography and certain types of indecent material depending on time, place and manner of

the presentation.

The second is blocking technology, including blocking software and some form of rating

system. The development of software that is designed to block unwanted sites. This blocking

software can block known adult sites, for isntance, or any site containing predetermined

words such as sex, gambling and other unwanted content. $ut none of these blocking systems

are completely effective. The Ceb changges +uite rapidly, and software designed for today

may not be entirely appropriate tomorrow.

The third !and the most important) is media literacy for both parents and their children as to

the benefits and sometimes problems of the .nternet. The role of parents in working with their

children and becoming familiar with this technology is critical. Children can be taught

Qcritical viewing skillsE in their schools so that they learn to better interpret what they

encounter on the Ceb . Rparents should begin to monitor, supervise and participate in their

children s .nternet activities.

0<. Wha% are %he /o*#%#-e *#de* o" In%erne% (*e&

The .nternet is perhaps the greatest teaching tool we have ever encountered. There are

numerous Ceb sites that allow children and teens to explore the world and create art and

literature: there are Ceb sites that foster creativity: the .nternet can also be an effective

learning tool that can facililtate academic achievement: learning through group participation,

learning through fre+uent interaction and feedback: .nternet can be a positive component in

children s lives by enabling them to keep in touch with friends, family and others to form

communities with common interests.

01. De*cr#e %he de-elo/!en% o" elec%ron#c $a!e*.

The first electronic game was introduced about (" years ago. .n the early >?#"s adult

consumers became fascinated with the first arcade version of !ong, which was basically a

simple visual < motor exercise. 3oon home systems and cartridge games became available,

and electronic games became popular across all age groups. .n the early >?@"s consumers

became disenchanted with copycat games and sales dropped. The industry recovered in the

8

second half of >?@"s when special effects were improved, new game accessories were

available, and games with violent content were promoted. .n addition, the industry introduced

cross < media marketing, with game characters featured as action figures and in the movies.

At the same time, the children became targeted consumers. $eginning with $ortal +ombat,

violent games with ever more realistic graphics became an industry staple. .n recent years,

sales of electronic games have exceeded several billion dollars annually worldwide.

0'. Who /lay* !ore& Aoy* or $#rl*&

$oys play more than girls at all ages. !>???.)

00. Ho+ are $a!e* cla**#"#ed&

Cright et al. !'"">) designed a game-coding system for use in their national survey conducted

in >??#. Their categories were designed to reflect the types of mental and sensorimotor

activities re+uired of the player and include the following9

- educationalMinformative

- sports

- sensorimotor !including actionMarcade, fightingMshooting, drivingM racing)

- other vehicular simulations

- startegy ! including adventureMrole playing, war, strategic simulations, pu88leMgames)

- unknown !other content, unspecified games, platform only).

04. Who are 4h#$h-r#*;5 /layer* &

Any child, boy or girl, who typically plays more than ' hours each day and who demonstrates

an extreme negative reaction if play is limited should be considered at risk for negative impact

simply due to time displacement from other developmentally appropriate activities. 2igh risk

players are children who are considered at risk for negative impact. Another indicator of high-

risk status is a strong preference for violent games. Children with lower frustration tolerance

and high general irritability appear to be at above-average risk for at least short-term negative

impact, including unpleasant and uncooperative behavior, particularly after a prolonged

period of play. These children;s electronic game play should be limited to shorter intervals, no

more than (" to B" min wihout a significant break.

03. Wha% ha//en* d(r#n$ $a!e /lay#n$&

.t has been proposed that immersion in electric games may precipipate an AJTEHE) 3TATE

%D C%G3C.%P3GE33.

Chen positive this may be an example of the QflowE. DJ%C is a term used to describe the

intense feelings of en&oyment that occur when a balance between skill and challenge is

attained in an activity that is intrinsically rewarding.

13C2%J%6.CAJ A$3%H1T.%G is altered state of conscious when one becomes totally

immersed in the present experience. This experience includes daydreaming and fantasi8ing.

2.62CA 21G%3.3-phenomenon for adults-the state in which a driver may travel for

some distance and then suddenly becomes aware that heMshe has not been paying any attention

to the typical demands of driving.

9

Chen an individual becomes psychologicaly absorbed the logical integration of thoughts,

feelings and experiences is suspended.

6ame playing may produce either a flow state or psychological absorption.

07. Why #* -#olence a//eal#n$&

.ndustry spokesman often cite catharsis or tension release as a benefit of exposure to many

forms of violent media, but this claim has been disproven in a si8able body of research.

%thers suggest that rating actually enhance the appeal of violent media !Qforbidden fruit,

explanation).

Dor childern it is more likely that violence is more appealing for different reasons. 1ersonal

history seems to be a key variable with callous children who have been over exposed to

violence looking for continuing arousal, whereas anxious and emotionally reactive children

are trying to master anxiety-provoking experiences.

At this point pessonal history of exposure to violence and the abilitiy to become absorbed and

achieve a flow state seem to be promising variables for future study.

08. Wha% are *hor%-%er!ed e""ec%* and +ha% are lon$-%er!ed e""ec%* o" /lay#n$ -#olen%

elec%ron#c $a!e*. E./la#n.

3hort-term effects are the immediate results of a specific game-playing experience,either

observable behavioral change or change in some specific aspect of thinking.

Jong-term effects are determined by examining relationships between certain behaviors,

personality characteristics or cognitions, and game-playing habits, such as a preference for

violent games.

Short-termed effects are9 more aggression toward ob&ects, imitation of the moves of game

characters. 1laying a violent electronic game caused an immediate increase in aggressive

behavior in younger children and they are more likely to attribute negative intent to the

actions of others. .t can also lead to the development of a hostile attribution bias, which could

lead to aggressive behavior. Dor example, when a child with a hostile attribution bias is

pushed accidentally on the playground, that child is more likely to push back because he will

view the accidental push as an intentionally negative action. Heslults of recent research on the

short-term effects of playing a violent e. game on children and adolescents are mixed. .n some

cases, short-term negative impact is clearly identified. .n other cases, there is a complex

relationship between preexisting characteristics and response to the game. Although causal

relationships can be studied in the laboratory, this setting cannot take into consideration all the

potential mediating and moderating variables that may be active in the real world.

-ong-term effects. Children with a strong preference for violent games rated themselves lower

in one or more of the following areas9 academic competence, behavioral conduct, social

acceptance, athletic competence and self.esteem. Also those adolescents whose favorite game

was violent had lower scores on a measure of trust empathy. 1laying violent games is likely to

increase aggressive behavior,thoughts,and feelings and decrease prosocial behavior. 3ome

authors consider that high fre+uency video game players are at increased risk for the

development of pathological gambling habits and other addictions.

09. Wha% are heal%h r#*;* o" /lay#n$ elec%ron#c $a!e*&

10

3ince electronic games first became popular, there have been various case reports of minor

negative health impact,primarily temporary musculoskeletal in&ury. There is one report of a

possible syndrome associated with playing computer games for long periods of time ! '-5

hours per day). This syndrome consists of headache, abdominal pain, tiredness, poor eating,

weight loss, nausea, low-grade fever, chest pain, and sweating of unknown origin. According

to the authors, all >? patients; symptoms completely disappeared within > week on

discontinuation of game play. Dor a small group of players, an increased risk of sei8ures has

been identified. .n a larger group, health risks associated with cardiovascular reactivity and

sedentary behavior have been proposed.

0:. Wha% #* "ree read#n$&

Dree reading after educator 3tephen Srashen;s definition9 when children choose their own

reading for the purpose of pleasure rather than to produce a book report or to answer specific

+uestions.

4<. Wha% do ch#ldren l#;e %o read %he !o*%&

The most preferred materials were scary stories and books, comics, maga8ines about popular

culture, and books and maga8ines about sports.

3econdary preferences included books about animals, drawing books, and, for boys, books

about cars.

The most fre+uent source for books and maga8ines was bookstores, rather than school

libraries.

As children mature into &unior high school years, both boys and girls begin to read mysteries,

and girls become increasingly attracted to preadolescent romance novels.

41. Wha% %y/e o" !a$aB#ne* do $#rl* l#;e %o read and +ha% %y/e do oy* l#;e&

Top five maga8ines for boys are .amepro, /intendo !o0er, "lectronic .aming $onthly, and

Sports &llustrated for +inds, and Sport1

.n a category of boy7s reading there is a utilitarian dimension of free reading. All of the first

three titles are designed to make the reader a better player and the last two offer advice in

sports.Dor girls the best sellers are Teen 2eat, Super Teen, Teen, ll bout 3ou and T0ist.

6irls7 maga8ines are more homogenous in that they offer about teenage celebrities, makeup

and dating tips and advice from the perspective of popular psychology.

4'. Wha% are Man$a and An#!e& G#-e e.a!/le*.

Man$a - contemporary Tapanese comics

An#!e - animated versions of manga stories

*anga portray a more complex and realistic view of life. .n manga, the death of a ma&or

character is fre+uently portrayed. *anga portray adults at work, using high-tech computer and

communication technologies. Characters have a Esecret lifeF where friend and foes help them

to defeat foes. Pnlike American superheroes, manga characters make errors and learn from

their mistakes: they grow morally and intellectually as stories develop. They are designed to

finish with character get married, going off to college or dying.

Examples9 !okemon, )igimon, 3u-.i-Oh, Transformers, Speed #acerN

11

40. Wha% #* %he d#""erence e%+een A!er#can and Ca/ane*e co!#c*&

The ma&or difference between Tapanese and American comics is that manga portray a more

complex and realistic view of life. .n manga, the death of a ma&or character is fre+uently

portrayed, whereas in American comics the topic is typically avoided.

*anga often portray adults at work, using high-tech computers and communication

technologies, an area of life that is nearly invisible in American comics. The people !generally

not superheroes) who populate manga work, go to school and interact with their parents.

Characters also have a Esecret lifeF where friends and robots help them to defeat foes. Does

are not necessarily depicted as the embodiment of evil: enemies of manga characters have

complex motives pursuing rational goals. Pnlike American superheroes manga characters

make errors and learn from their mistakes: they grow morally and intellectually as stories

develop. .8awa believes that the EeverydaynessF of manga may be a liberating factor in

readers7 identification with characters and events. Dinally, unlike American superhero comics,

manga stories deliberately end. They are designed to finish with a character getting married,

going off to college or even dying.

44. Wha% are %he ;ey ele!en%* o" !y%h#c or hero#c *%ory&

*ythic heroes must respond to a call to adventure and cross thresholds, often overcoming a

guardian. Cith the help of assistants, they overcome a series of tests leading to the supreme

ordeal to achieve a reward. Then they make a return &ourney and a reemergence in their now

peaceful everyday world. !There are signs of this mythic pattern in a comic series like

3uperman)

43. Ho+ doe* %ele-#*#on -#e+#n$ Dhea-y -#e+er*E a""ec% ch#ldren'* read#n$ *;#ll*&

Early investigations, when television was new, indicated little or no relationship between the

two activities. Contemporary critics point out the fallacy of inffernig the behavior of modern

children from early correlational research. Chen chlidren;s television is removed or

decreased, reading increases, so it is tempting to extend the conclusion to a T--detracts.form-

reading hypothesis. %ne investigation of students in grades ( to 5 found a relationship

between T- viewing and reading9 Time spent reading was inversely correlated with the

viewing of aggresive Tv programs, and the number of books read was inversely correlated

with viewing of game shows. The authors interpret their results as evidence for television;s

displacing some of the exciting and amusing aspects of books. .n more recent research there si

accumulating evidence for the decline of reading ability as a function of T- viewing. .n the

only published meta-analysis television viewing was negatively correlated with reading

ability and other dimensions of academic achievement, and the magnitude of the correlation

rises sharply after '" hours per week of viewing. A review of more than ( decades of research

also found a consistent negative relationship and concludes that viewing more than ( hours

per day may be the critical peak in the decline of reading ability. .n a longitudinal study of

parent-child communication and its implications for media use, preschool children who were

heavy viewers of television were less capable readers than lighter viewers by first grade.

Television may nfluence the kind of reading that children prefer, not only the amount.

*organ found that young adolescents who are heavy viewers of television prefer reading that

12

resembles television content !i.e. stories about love and romance, with teenage themes,...).

Jighter viewers chose fiction and poetry for free reading, and they selected more overall

categories of reading that did their heavy-viewing counterparts.

47. Wha% are %he %y/e* o" #!a$#na%#on&

1E I!a$#na%#-e /lay !fantasy play, pretend play) can be defined as play in which children

transcend the constraints of reality by acting Eas ifE. .n it, children pretend that they are

someone else, that an ob&ect represents something else or that the participants are in a

different place and time. Children who exhibit a great deal of imagination in their play are

better able to concentrate, develop greater empathic ability, and are better able to consider a

sub&ect form different angles. They are happier, more selfassured and more flexible in

unfamiliar situations. There are indications that a high level of imagination in childhood is

positively related to creativity in adulthood. Children;s imaginative play is ibfluenced by

environmental and developmental factors. .t has been suggested that the Eas ifE nature of

imaginative play helps the child in breaking free of established associations or meanings and

thereby encourages children;s creativity in the long term.

'E Daydrea!#n$ !or fantasi8ing) refers to mental processes such as musing, mind wandering,

internal monologue, and being lost in thought. )aydreaming is a state of consciousness

characteri8ed by a shift of attention. .nstead of focusing on external stimulation or on a

physical or mental task, the child;s attention turns to thoughts and images that are based in

memory.

0E Crea%#-#%y !or creative imagination) is defined as the capacity to generate many different

novel unusual ideas. Creativity seems to start around 5 or B years of age. 3ome researches

believe that younger children cannot be cretaive because they ae unable to differentiate outer

stiumuli from the internal experience of the stimuli. )aydreaming and creativity overlap to

some extent. $oth types of imagination re+uire the generation of ideas, and, in both activities,

associative thinking plays a role.

48. Ho+ doe* %ele-#*#on -#e+#n$ e""ec% ch#ld'* #!a$#na%#on& E./la#n o%h $ood and ad

*#de*.

Television viewing is believed to produce a passive intellect and to reduce imaginative

capacities. %n the other hand, there has been enthusiasm about educational television viewing

fostering children;s crreative thinking skills. Children use television content in their

imaginative play and creative products. Children who exhibit a great deal of imagination in

their play are better able to concentrate and are better able to consider a sub&ect from different

angles. They are happier and more flexible in unfamiliar situations. 2igh level of imagination

play in childhood is positively related to creativity in adulthood. Television viewing also has

bad effect on child;s imagionation because of presence of violence in many programs,

moviesN

49. Wha% #* %he e*% +ay %o learn a lan$(a$e& In +ha% +ay doe* T, hel/ ch#ldren %o

learn a lan$(a$e&

Janguage is best learned through conversations carried out between interacting people, one of

whom is the language learned himself or herself. oung children fre+uently are active

13

participants as they watch television < and those studed rarely watch alone.T- influences on

grammatical development and lexical development !children can learn about words and their

meanings). This is considered when we are talking about effects of educational Tv programs.

4:. Wha% #* -#$#lance& Wha% are %he "ac%or* #n-ol-ed #n -#$#lance&

,#$#lan% !n) - argus-eyed9 carefully observant or attentive: on the lookout for possible danger:

factors involved in vigilance9

viewer related factors9 gender, temperament and personality, intelligence, age:

programing-related factors9 content features of programming, emotionally negative

and positive content:

situational factors9

3<. Wha% #* a ,-ch#/&

,-ch#/ is a generic term used for television receivers allowing the blocking of programs

based on their ratings category

31. Wha% #* %he 0-ho(r r(le&

A second regulation re+uries commercial broadcasters to Qserve the educational and

informational needs of childrenE by offering a minimum of ( hours a week of educational

television and identifying educational programs on the air. To count toward the ( hour,

programs must air between the hours of #9"" A.*. and >"9oo 1.*., must have Qeducational as

a significant purposeE, and must be specifically designed for children. $roadcast may air

somewhat less than ( hours a week, but they must then submit to a full licence review and

provide evidence that they are serving the child audience in other ways. 1rogrammers began

airing ( hours a week of educational and informational programming beginning in the >??#-

>??@ season.

3'. Wha% are *o!e o" %he /ro*oc#al e""ec%* o" %ele-#*#on&

%ver the years, public and scholary attention has focused on the accumulation of evidence

that television contributes to violence and hostility. The possibility that television viewing

may also foster friendly, prosocial interactions has recived less attention. As we have ar+ued

elsewhere there is no unherent reason why television viewing should have only negative

effects. After all, most negative effects of viewing are explained by two basic mechanisms.

%ne is that we leran by observation how to do things and whether it is appropriate to do them.

The second is that we have emotional responses while watching television that effect our

responses to similar real-world events. As Hushton !>?#?) pointed out, both of these

mechanisms are relevant to the viewing of prosocial material as well. .n fact, Hushton

suggested that prosocial content could potentially have stronger effects on viewers than

antisocial content because prosocial behaviors are more in accord with established social

norms. .ndividuals who respond with aggression to friendly overtures or to re+uests for help

14

are less likely to be rewarded by others members of society than are those who respond more

positively.

30. Wha% are 0 !ayor e.a!/le* o" /ro*oc#al /ro$ra!!#n$& E./la#n #n +ha% +ay do

%he*e /ro$ra!* hel/ ch#ldren&

>. 3esame 3treet - .n its original conception, the program emphasi8ed certain cognitive

skills that would provide the basis for school curriculum such as knowledge of letters and

numbers. $ankart and Anderson also studied children7s aggression levels during free play and

reported that four episodes of 3esame 3treet shown over a 4-day period significantly reduced

boys7 and girls7 aggression.

'. *ister Hogers7 Geighborhood

3ocial and affective messages are the primary focus of *ister Hogers7 Geighborhood.

Children who watched that showed several positive changes. they persisted longer on tasks,

were more likely to obey rules and were more likely to delay gratification without protest. .n

all ( of these studies *r. Hogers did have some positive effects but the effects were much

stronger when viewing was accompanied by activities designed to explicitly teach the types of

behaviors modeled in the program.

(. $arney U Driends

$arney is a purple dinosaur who comes to the aid of a sprightly set of multicultural children.

.t is most notable for the absence of conflict, the emphasis on cooperation and the expression

of positive affect. Children showed the strongest gains when viewing was combined with

follow-up lessons, moderate gains from viewing without the lessons and negligible gains &ust

from the lessons. $arney U Driends emphasi8es positive affect and positive interaction.

2appy children hug and sway on-screen, singing the E. Jove ou, ou Jove *eF song.

34. Fo( ha-e %o do #% y yo(r*el"6

33. Wha% #* %he !o*% *#$n#"#can% chan$e #n "a!#ly l#"e re$ard#n$ %ele-#*#on -#e+#n$ #n %he

ho(*e&

%bservations in the early >?5";s held that the television set fro8e the natural order of family

interaction < talking, &oking, arguing, catching up on the disparate experiences of each family

member. Chen the T- is on, there is Emore privati8ation of experience: the family may

gather around the set but they remain isolated in their attention to it.E The sociali8ing role of

the family had been supplanted by the mass media, advertisers and celebrities. Chen

2olmanUTac+uart indicated tham marriages might stay stronger if spouses were involved in

lisure-time activities, thereby increasing interpersonal communication rather than +uickly

watching T-, the popular press +uickly declared that less television was a key to improved

marriages and stable families.

37. Wha% are ar$(!en%* %ha% *ho+ %ha% %ele-#*#on -#e+#n$ r#n$* "a!#ly !e!er*

%o$e%her and +ha% are ar$(!en%* a$a#n*% #%&

Television also brings families together. Television;s unifying effect on the family was

observed as early as >?4?: the medium acted as a catalyst in bridging generational gaps.

Among those who wished to increase contact with the family, television use of other media.

15

%ther schools who have pointed out that greater family solidarity may be achieved via

television-induced interaction and conversation include $rady, 3toneman U 3auders. As

Coffin argued in >?55, television viewing can often do both. Television can be Ecredited with

increasing the family;s fund of common experience and shared interests and blamed for

decreasing conversation and face-to-face interaction. .ndeed Hosenblatt and Cunningham

suggested that television viewing can also serve as a means to avoiding tense interaction in

crowded homes where conflict avoidance through spatial separation is imposible. %ne cannot

really separate the chicken from the egg, and the assumptions of clean cause-effect

relationships are &ust that, assumptions. Television brings family members together as there is

that it reads them apart. *ore time spent viewing is correlated with more time spent viewing

with the family. As a result a lot of content particularly through the first two decades of the

medium;s history in the P3, is articulated particularly well with conversational family

interestd and values. Adolescents who watch more television report feeling better during time

spent with the family and better with friends.

38. Wha% e-en%* and /er*on* !ade %he !o*% no%ale *h#"%* #n %he 1:3<'* and 1:7<'*

!ed#a& Ho+ d#d %he !ed#a ca/#%al#Be on %ha%&

Drom a family perspective, the most notable shifts in the >?5"s and >?B"s media were the rise

of rock ;n; roll < still the art form of choice for adolescents as they begin to rebel and make

their break from identifying with the family to the peer group < and youth culture movie stars

as *arlon $rando and Tames )ean, whose films chronicled youth angst, delin+uency, and,

notably, significant problems of the family unit. .n >?5"s America, the film industry, even in

the wake of 3enator *cCarthy;s attacks, no longer needed to churn out only optimistic visions

of the American way of life, as they had done in a time of war.

39. Wha% #* %he d#""erence #n *ho+#n$ a %y/#cal "a!#ly #n T- *ho+* #n %he 1:3<'* and

%oday&

.n the >?5"s, T- showed an ideal world to which, it was incorrectly assumed, everyone

inspired. Damilies were together !almost exclusively white), they loved each other, they lived

in safe neighborhoods, and kids, and kids could count on adults to help them through trials

and tribulations of adolescence. $ut not only were those images something very difficult to

live up to, they were also often unrealistic and overly sentimental. Television producers

increasingly dispel the myths of middle.American perfection, as well asthe myth of a singular

desirable way of life. .n the postmodern television landscape, the chaos of the world is

depicted more fre+uently in the medium;s fictional offerings. The once-sacred nuclear family;s

role as a haven against the threats and disorder of the world is +uestioned and alternatives are

sometimes considered.

Although the image of the family has changed on T- the industry;s reliance on the family in

programs and plots and on family viewership and patronage of advertised goods has not. Got

all T- genres can easily accomodate families or family themes. 1olice or action-adventure

shows, for example, glorify single males and bachelorhood. .n police dramas, single life is

preferred, with fewer than one out of five ma&or characters being married. Jiving the single

life in this genre has the advantage over marriage and domesticity. 3ingle men on television

16

are more effective and powerful. 3ituations comedies and soap operas are the perfect vehicles

to deal with the family, and it is hard to imagine these genres without family life in the center.

3:. !('@.str)

a.E Wha% are *#%co!* "a!#ly *ho+*&

A situation comedy, usually referred to as a *#%co!, is a genre of comedy programs which

originated in radio. Today, sitcoms are found almost exclusively on television as one of its

dominant narrative forms.

3itcoms usually consist of recurring characters in a common environment such as a home,

living room and kitchen or workplace and generally include laugh tracks or studio audiences.

The sitcome world is one in which the most disturbing behaviors of contemporary society,

and the rest of T- world- murder, rape, domestic violence and child abuse < )% G%T TASE

1JACE. The internal world of a family sitcome is one of the most desirable places one could

hope to inhabit.

.E Wha% are %y/e* o" *#%co!*& D0':. *%r.E

3pecific categories by Chesebro and 3teendlan)9

>.) The childless couples4

communal families

geriatric families

unmarried men

and woman

'.) s parents4

aggregate and EblendedF families

7<. Wh#ch %+o %y/e* o" !(*#c are !o*% %he /role!a%#c "or /aren%* & Why&

%f all types of music that teenagers listen to, heavy metal and rap music have elicited the

greatest concern: they seem to pride themselves in explicit and sexually violent themes. %ne

study showed that heavy metal fans had more thoughts of suicide. Hap music- At times, it7s

angry and violent, hard <core rap music is now driven almost exclusively by sex, violence and

materialism.

71. Wh#ch $ro(/ l#*%en* %o !(*#c !ore %han +a%che* T,& Wha% are *o!e o" %he !o%#-e*

"or l#*%en#n$ %o !(*#c&

Adolescents during mid-to-late adolescence.

Koung peopleK use music to resist authority at all levels, assert their personalities, develop

peer relationship and romantic entanglements, and learn about things that their parents and

schools are not telling them.

Adolescents like rock music because relaxation and mood regulation, social!partying, talking

to friends, playing), silence filling!background noise, relief from boredom),

expressive!identification with a particular sound, lyrics or musical group), sociali8ation.

7'. De*cr#e an a-era$e MT, !(*#c -#deo ne+ day*.

17

*usic videos now days contain more violence, guns, sex, alcohol, drugs, cigarettes and

profanity. The main issue of a lot videos are sex and sexuality.

18

Anda mungkin juga menyukai

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDari EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (5794)

- Olweus Research HistoryDokumen2 halamanOlweus Research Historykso87100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDari EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (537)

- Olweus Bullying ReviewDokumen4 halamanOlweus Bullying Reviewkso87Belum ada peringkat

- Method Guide PreviewDokumen4 halamanMethod Guide Previewkso87Belum ada peringkat

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Dari EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Penilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (98)

- New Developments of The Shared Concern Method: Department of Education, Uppsala UniversityDokumen20 halamanNew Developments of The Shared Concern Method: Department of Education, Uppsala Universitykso87Belum ada peringkat

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDari EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RacePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (895)

- AMS ANALITICA-AIRFLOW TSP-HVS BrochureDokumen1 halamanAMS ANALITICA-AIRFLOW TSP-HVS BrochureShady HellaBelum ada peringkat

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDari EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (344)

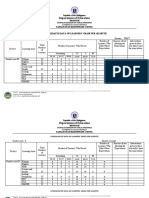

- Department of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterDokumen4 halamanDepartment of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterUsagi HamadaBelum ada peringkat

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDari EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (399)

- CycleMax IntroDokumen13 halamanCycleMax IntroIslam AtefBelum ada peringkat

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDari EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseverancePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (588)

- Keeping Track of Your Time: Keep Track Challenge Welcome GuideDokumen1 halamanKeeping Track of Your Time: Keep Track Challenge Welcome GuideRizky NurdiansyahBelum ada peringkat

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDari EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (271)

- PTW Site Instruction NewDokumen17 halamanPTW Site Instruction NewAnonymous JtYvKt5XEBelum ada peringkat

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDari EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (266)

- Sensitivity of Rapid Diagnostic Test and Microscopy in Malaria Diagnosis in Iva-Valley Suburb, EnuguDokumen4 halamanSensitivity of Rapid Diagnostic Test and Microscopy in Malaria Diagnosis in Iva-Valley Suburb, EnuguSMA N 1 TOROHBelum ada peringkat

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDari EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (838)

- Radio Ac DecayDokumen34 halamanRadio Ac DecayQassem MohaidatBelum ada peringkat

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDari EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (231)

- ChatGPT & EducationDokumen47 halamanChatGPT & EducationAn Lê Trường86% (7)

- Acoustic Glass - ENDokumen2 halamanAcoustic Glass - ENpeterandreaBelum ada peringkat

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDari EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (73)

- Ethernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application TechniqueDokumen50 halamanEthernet/Ip Parallel Redundancy Protocol: Application Techniquegnazareth_Belum ada peringkat

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDari EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FuturePenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (474)

- End-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFDokumen12 halamanEnd-Of-Chapter Answers Chapter 7 PDFSiphoBelum ada peringkat

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDari EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnPenilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (234)

- MATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFDokumen7 halamanMATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFGiftBelum ada peringkat

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDari EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyPenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (2259)

- Basic Terms/Concepts IN Analytical ChemistryDokumen53 halamanBasic Terms/Concepts IN Analytical ChemistrySheralyn PelayoBelum ada peringkat

- Swelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12Dokumen100 halamanSwelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12ERICKBelum ada peringkat

- Rise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnoreDari EverandRise of ISIS: A Threat We Can't IgnorePenilaian: 3.5 dari 5 bintang3.5/5 (137)

- Blake Mouton Managerial GridDokumen3 halamanBlake Mouton Managerial GridRashwanth Tc100% (1)

- Static Electrification: Standard Test Method ForDokumen10 halamanStatic Electrification: Standard Test Method Forastewayb_964354182Belum ada peringkat

- Audi A4-7Dokumen532 halamanAudi A4-7Anonymous QRVqOsa5Belum ada peringkat

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDari EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (45)

- G.Devendiran: Career ObjectiveDokumen2 halamanG.Devendiran: Career ObjectiveSadha SivamBelum ada peringkat

- Tribes Without RulersDokumen25 halamanTribes Without Rulersgulistan.alpaslan8134100% (1)

- Installing Surge Protective Devices With NEC Article 240 and Feeder Tap RuleDokumen2 halamanInstalling Surge Protective Devices With NEC Article 240 and Feeder Tap RuleJonathan Valverde RojasBelum ada peringkat

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDari EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You ArePenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (1090)

- Aristotle - OCR - AS Revision NotesDokumen3 halamanAristotle - OCR - AS Revision NotesAmelia Dovelle0% (1)

- File RecordsDokumen161 halamanFile RecordsAtharva Thite100% (2)

- Engineering Management: Class RequirementsDokumen30 halamanEngineering Management: Class RequirementsMigaeaBelum ada peringkat

- Homework 9Dokumen1 halamanHomework 9Nat Dabuét0% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Dari EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Penilaian: 4.5 dari 5 bintang4.5/5 (120)

- Taylor Series PDFDokumen147 halamanTaylor Series PDFDean HaynesBelum ada peringkat

- Use of The Internet in EducationDokumen23 halamanUse of The Internet in EducationAlbert BelirBelum ada peringkat

- Meta100 AP Brochure WebDokumen15 halamanMeta100 AP Brochure WebFirman RamdhaniBelum ada peringkat

- BECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFDokumen11 halamanBECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFAmeil OrindayBelum ada peringkat

- Documentation Report On School's Direction SettingDokumen24 halamanDocumentation Report On School's Direction SettingSheila May FielBelum ada peringkat

- Quality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFDokumen41 halamanQuality Standards For ECCE INDIA PDFMaryam Ben100% (4)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDari EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesPenilaian: 4 dari 5 bintang4/5 (821)