2012-2013 Collaborative Planning Guidebook

Diunggah oleh

Donche RisteskaHak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

2012-2013 Collaborative Planning Guidebook

Diunggah oleh

Donche RisteskaHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Collaborative Planning

Guidebook

The experts

are among

us

August 2012

Table of Contents

Introduction

FRAMEWORK FOR COLLABORATIVE PLANNING

2012-2013 Schedule for Collaborative Planning 1

The Main Ideas 2

Overview of the Collaborative Planning Process 9

First Things First: Demystifying Data Analysis 10

Three Big Ideas and Four Crucial Questions 14

Creating SMART Goals 15

TEAMWORK TOOL KIT

Annual Improvement Goals Form 16

Analyzing the PASS or HSAP School Demographic Report 17

Guidelines for Interpreting MAP Reports 20

Guiding Questions for Analysis of MAP Growth 23

SCDE Testing Information 26

State Writing & Final Rubric Grades 3-10 27

HSAP Extended Response Scoring Rubric 28

Team Roles 29

Brainstorming Guidelines 31

Feedback / Rewards, Recognition & Celebration 32

Collaborative Planning Lesson Study Protocol 33

The Tuning Protocol 36

The Consultancy Protocol 38

Effective 30-Minute Meeting Protocol 40

Connections Protocol 41

Team Learning Log Form 42

Collaborative Planning Learning Log 42

Special Request Form 44

Suggested Resources 45

COLLABORATION IN ACTION

Tab 1

Framework for Collaborative Planning

tab goes here.

Introduction

The purpose of this guide

This revision is a work-in-progress that represents continuing progress in

using a powerful concept and process for improvement of student learning at

all levels. The concepts are based largely on the work of Michael Schmoker,

cited throughout the guide. His work has been elaborated and extended by

numerous well-respected educators.

The process advocated in this guide has been used effectively in many

schools. Experience in Lexington County School District One and elsewhere

has shown that the process is most effective when it centers on the use of

collaborative assessments, which provide valuable data to inform instructional

planning. This guide is a compilation of resources for collaborative planning at

the school level. Because different schools will bring varying levels of

expertise and experience to the planning process, this guide is not intended

to be necessarily prescriptive. Read it quickly to get a sense of the overall

process and then work through it in stages.

Guidebook Overview

I. Framework for Collaborative Planning

Section I of the Guide provides background information to assist you in

understanding the planning process and timelines as well as providing for

you the concepts of collaborative planning based on research to improve

instruction. A clear understanding of this mindset will provide a framework

for efficient and meaningful meetings and ultimately effective results.

II. Teamwork Tool Kit

No meaningful product or results can be achieved without the proper

tools. In this section you will find the tools that will assist you in planning

together, as well as a description of the various roles and components of

the collaborative planning process. Protocols for meeting activities and

forms for recording goals and progress are included.

Teacher teams will develop other useful tools as they work together. You

are invited to share the tools that you develop with colleagues and

recommend them as resources to be included in future guides.

III. Collaboration in Action

This is YOUR section. Maintain your team goals, lesson plans, and

assessments, and notes in this section. Other information housed here

might include test data on your specific students, copies of minutes from

previous meetings and rubrics.

When teachers regularly and collaboratively review assessment data for the purpose

of improving practice to reach measurable achievement goals, something magical

happens.

-Michael Schmoker, The Results Fieldbook

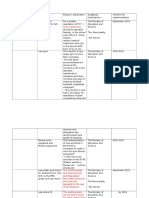

Collaborati ve Planning Schedule

1

2012-2013

September 5, 2012

October 3, 2012

November 7, 2012

December 5, 2012

February 6, 2013

March 6, 2013

May 1, 2013

Early Release:

Elementary schools 11:40 a.m.

Middle and High schools 12:40

2

The Main Ideas

NOTE: A new list of resources that have been used effectively

by various groups in Lexington County School Distric One has

been added as the last section of this guidebook.

The section below is a collection of key points from several

publications by Mike Schmoker, a widely recognized authority

on collaborative planning. The quotations were selected because

they focus on what actually happens in the collaborative

planning process.

Results, p. 55

When the three concepts of teamwork, goal setting, and data use

interact, they address a misunderstanding prevalent in schools. The

misunderstanding is that we can improve without applying certain basic

principles: People accomplish more together than in isolation; regular,

collective dialogue about agreed-upon focus sustains commitment and

feeds purpose; effort thrives on concrete evidence of progress; and

teachers learn best from other teachers. We must ensure that these three

concepts operate to produce results.

Results Now, p. 25

You have to give educators credit; for all the superficial comforts of being

left alone, they will admit that constructive collaboration would lead to

greatly improved instruction.

By elevating privacy and isolation in the name of professionalism, we have

allowed teaching to acquire an outsized aura of mystique and complexity,

a sense that effective teaching is primarily personal and beyond scrutiny.

It has become increasingly difficult to ask practitioners to conform to even

the most well-established elements of good instruction: being clear

and explicit about what is to be learned and assessed; using

assessments to evaluate a lessons effectiveness and making

constructive adjustments on the basis of results; conducting a check

for understanding at certain points in a lesson; having kids read for

higher-order purposes and write regularl y; and clearl y explicating

and carefull y teaching the criteria by which student work will be

scored or evaluated.

3

Results, p. 114

The Experts Are Among Us

One of the reasons that such teamwork and lesson study are so effective

is that they tap into teachers existing capabilities and potential, which are

more apt to flourish in teams than under external trainers...

Dennis Sparks, who deeply understands effective staff development, put it

starkly for me once: he said that any faculty could begin improving

performance, tomorrow morning, if they never attended another workshop

in their lives. They would improve, inexorably, simply by deciding on

what they wanted students to learn and then working together to

prepare, test, and refine lessons and strategiescontinuously, toward

better results.

Teamwork

Results Now, p. 108

We have to be very clear about what true teamwork entails: a regular

schedule of formal meetings where teachers focus on the details of their

lessons and adjust them on the basis of assessment results. The use of

common assessments is essential here. Without these, teams cant

discern or enjoy the impact of their efforts on an ongoing basis. Enjoying

and celebrating these short-term results is the very key to progress, to

achieving momentum toward improvement (Collins, 2001a)

Results Now, p. 106-107

But what are true learning communities, and why are they more

effective than traditional staff development? We cant afford, as Rick

DuFour points out, to corrupt or co-opt the fundamental concepts of

collaborative learning communities (2004). What are those fundamental

concepts?

First, professional learning communities require that teachers establish a

common, concise set of curricular standards and teach to them on a

roughly common schedule. Teams need to consult their state assessment

guides and other documents to help them make wise decisions about

what to teach (and what not to teach).

Then they must meet regularly. I suggest that teams meet at least twice a

month, for a minimum of 45 minutes, to help one another teach to these

4

selected standards (I have seen great things come of 30-minute

meetings). This time must be very focused: most of it must be spent

talking in concrete, precise terms about instruction with a concentration

on thoughtful, explicit examination of practices and their consequences

the results achieved with specific lessons and collaborative analysis of the

results of our efforts, what can we do to improve students learning?

(2002, p.21). To perform this work, teachers must make frequent use of

common assessments. These assessmentsare pivotal. With common

assessments and results, teachers can conduct what Eaker calls active

research where a culture of experimentation prevails. (2002, p.21).

Results Now, p. 115-116

Teachers know a lot about good practice. But school systems, ever-

seduced by the next new thing, dont provide them with focused,

collaborative opportunities that remind and reinforce the implementation of

the most basic and powerful practices.

Is it accurate to assume the following?

The majority of teachers know that students need to do lots of

purposeful reading and writing.

The script of a lesson or unit must include a clear explanation of the

specific standard.

Modeling and step-by-step demonstration of new skills is essential.

Short practice opportunities combined with a check for

understanding ensure that more kids learn and fewer are left

behind.

Teachers know that a good lesson includes an assessment that aligns

with the standards just taught. Most teachers have learned a few

strategies for keeping kids attentive.Most have learnedthat we should

frequently provide exemplars of good work and that we need to be very

clear about our grading and evaluative criteria if we want them to succeed.

Classroom studies continue to reveal that these basic, powerful practices

are still all too rare.

Results Now, p. 111-112

In my workshops, I like to do a pared-down version of lesson study. I

take teachers through an entire team meetingfrom identifying a low-

scoring standard, to roughing out an appropriate assessment, to building a

lesson designed to help as many students as possible succeed on the

assessment. We do all thissomewhat crudelyin less than 20 minutes.

5

Once completed, we take a break, and then we posit that the lesson didnt

work as well as wed like. So we make a revision or two.

The results can be surprising: teachers see that in even so short a time,

they can collectively craft fairly coherent, effective standards-based

lessons and assessments.Lights go on: they realize that learning to

make such focused, constructive effort virtually requires teamwork, that

the members not only contribute a richer pool of ideas buthugely

importantsocial commitment and energy, as essential elements of

success (Fullan, 1991.p 84).

Results, p. 17

Another problem is lack of follow up, the failure to begin each meeting

with a concise discussion of what workedand didnt. Too many

meetings begin with no reference to commitments made at the last

meeting. A teacher.was tired, he said, of filling chart paper with ideas

and this is the end of itno follow-up on if or how well the ideas had even

been implemented or if they had in fact helped students learn.

Careful, methodical follow-uphas not been educations strong suit. But

if we want results, a scientific, systematic examination of effort and effects

is essentialand one of the most satisfying professional experiences we

can have.

Goal Setting

Demystifying Data Analysis,

If we take pains to keep the goals simple and to avoid setting too many of

them, they focus the attention and energies of everyone involved (Chang,

Labovitz, & Rosansky, 1992; Drucker, 1992; J oyce, Wolf, & Calhoun,

1993). Such goals are quite different from the multiple, vague, ambiguous

goal statements that populate many school improvement plans.

Results Now , p. 122

"The case for generating a steady stream of short-term wins is not new

and is pure common sense. If anything, it is mystifying that schools have

yet to institute structures that allow people to see that their hard work is

paying offthis week or monthnot next year or five years from

now.Gary Hamel exhorts us to Win small, win early, win often (as cited

in Fullan, 2001, p.33). For Bob Eaker, our goals themselves should be

designed to produce short-term wins (2002, p. 17). And now J im Collins

6

tells us to scrap the big plans in favor of producing a steady stream of

successes, which in turn will create the magic of momentum toward

enduring organizational success (in Schmoker, 2004. p. 427).

Results, p. 41

Allow teachers, by school or team, as much autonomy as possible in

selecting the kind of data they think will be most helpful. The data must

accurately reflect teacher and student performance and be properly

aligned with state, district, and school goals and standards. Establish

clear criteria that promote a relevant, substantive focus.

Results, p. 31

Criteria for Effective Goals

Measurable

Annual: reflecting an increase over the previous year of the

percentage of students achieving masteryusually in a subject

area

Focused, with occasional exceptions, on student achievement

Linked to a year-end assessment or other standards-based means

of determining if students have reached an established level of

performanceusually within a subject area

Written in simple, direct language that can be understood by almost

any audience

Data Use

Demystifying Data Analysis,

First things first: Which data, well analyzed, can help us improve teaching

and learning? We should always start by considering the needs of

teachers, whose use of data has the most direct impact on student

performance. Data can give them the answer to two important

questions:

How many students are succeeding in the subjects I teach?

Within those subjects, what are the areas of strength or

weakness?

7

The answers to these two questions set the stage for targeted,

collaborative efforts that can pay immediate dividends in achievement

gains.

Demystifying Data Analysis,

Turning Weakness into Strength

After the teacher team has set a goal, it can turn to the next important

question: Within the identified subject or course, where do we need to

direct our collective attention and expertise? In other words, where do the

greatest number of students struggle or fail within the larger

domains? For example, in English and language arts, students may have

scored low in writing essays or in comprehending the main ideas in

paragraphs. In mathematics, they may be weak in measurement or in

number sense.

Every state or standardized assessment provides data on areas of

strength and weakness, at least in certain core subjects. Data from district

or school assessments, even grade books, can meaningfully supplement

the large-scale assessments. After team members identify strengths and

weaknesses, they can begin the real work of instructional

improvement: the collaborative effort to share, produce, test, and

refine lessons and strategies targeted to areas of low performance,

where more effective instruction can make the greatest difference for

students.

Results, p. 80

The primary value of rubrics is their capacity to provide clear, useful

feedback that can be analyzed to identify areas of strength and weakness

at any time, at any level, for any number of audiencesfrom students to

whole communities.

Results, p. 43

To be sure, teachers do have data, such as Individual Education Plans

(IEPs), grades, grade-point averages, and test scores. Though such

individual data are useful, they are seldom converted into the kind of

group data that is necessary for more formal and collective reflection and

8

analysis. Even such easily gathered, conventional data are seldom

collectively analyzed to help teams or schools find better ways to address

collective problems. They could be.

Teachers tend to evaluate students individually and reflect on how to

improve class performance less frequently. We would expect, writes

Lortie (1975) to find heavy emphasis on results attained with classes, as

opposed to results with individual students.Lortie found that educators

do not seek to identify and address patterns of success and failure, which

can have broad and continuous benefits for greater numbers of children.

Not focusing on patterns is unfortunate, because the real power of data

emerges when they enable us to see--and addresspatterns of

instructional program strengths and weaknesses, thus multipl ying

the number of individual students we can help.

Resources

Schmoker, M. (1999). Results: The key to continuous school

improvement. Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and

Curriculum Development.

Schmoker, M. (2001). The results fieldbook: Practical strategies from

dramatically improved schools. Alexandria, VA: Association of

Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Schmoker, M. (2003). Demystifying data analysis. Educational

Leadership, 60(5), 22-25.

Schmoker, M. (2006). Results now: How we can achieve unprecedented

improvements in teaching and learning. Alexandria, VA:

Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Overview of the Collaborati ve Planning Process

Extracted from a presentation by Mike Schmoker in Columbia, SC, 2006.

9

Schmoker encourages teachers to have a clear understanding of the end-of-

year goal. End-of-course assessments are particularly important in upper

grades, but may be useful in elementary grades also.

I. Many authorities, including Mike Schmoker and Rick Dufour and

Rebecca DuFour recommend that teams create end-of-course or end-

of-semester assessments for every course taught.

These assessments must align with only the most essential, enduring

standards on state assessments. For courses not assessed by the state

accountability system,teams should/could create end-of-course

assessments based on a careful review of standards and the selection

ofonce againonly the most essential standards to be taught in each

course. These assessments should:

be completed by the end of first quarter in at all possible; work

can be completed during team meetings

include a clear and sufficient emphasis on higher-order proficiencies;

analysis, evaluation, and synthesis, which has to include writing and

real-world problem-solving (English/language arts should focus almost

exclusively on higher-order proficiencies and assessments.)

Finally divide essential standards into quarterly blocks & create quarterly

assessments; quarterly results should be reviewed by teams & leaders to

gauge progress & identify need for support/improvement.

II. At the beginning of the school year/after end-of-course assessments

are created, have ALL STAFF analyze state and end-of-course

assessment data to complete a form like ..Annual Improvement

Goals to

1. set a limited number of measurable, end-of-course/subject-area

goals (not more than two)

2. listfor each course goalspecific, lowest performing areas to

improve on this year

Establish dates and times for team meetings; these are sacrosanct. Then be

sure that every teacher brings the following Teamwork Tool Kit to every

meeting:

Team norms/protocols/brainstorming guidelinesessential to time-

efficient, productive meetings

Annual Improvement Goal form (with goals and areas of weakness

based on data analysis)

Interpretive guide(s) /sample assessments/scored writing samples

provided by the state

Rubrics, anchor papers, samples of student work wherever

appropriate

Team Learning Logs

Regularly collect and review Team Learning Logs at both building and

district level.

At every school and district meeting, regularly share, celebrate, and reward

measurable successes recorded on Team Learning Logs; be sure to

disseminate successes to all who teach the same skills or grade levels.

http://pdonline.ascd.org/pd_online/contemp_s_lead/el200302_schmoker.html

10

February 2003 | Volume 60 | Number 5

Using Data to Improve Student Achievement Pages 22-24

First Things First: Demystifying

Data Analysis

To improve student achievement results, use data to focus on

a few simple, specific goals.

Mike Schmoker

I recently sat with a district administrator eager to understand her

district's achievement results. Pages of data and statistical breakdowns

covered the table. Looking somewhat helpless, she threw up her hands

and asked me, "What do I do with all this?"

Many educators could empathize with this administrator. The experts' tendency to complicate

the use and analysis of student achievement data often ensures that few educators avail

themselves of data's simple, transparent power. The effective use of data depends on simplicity

and economy.

First things first: Which data, well analyzed, can help us improve teaching and learning? We

should always start by considering the needs of teachers, whose use of data has the most direct

impact on student performance. Data can give them the answer to two important questions:

How many students are succeeding in the subjects I teach?

Within those subjects, what are the areas of strength or weakness?

The answers to these two questions set the stage for targeted, collaborative efforts that can pay

immediate dividends in achievement gains.

Focusing Efforts

Answering the first question enables grade-level or subject-area teams of practitioners to

establish high-leverage annual improvement goalsfor example, moving the percentage of

students passing a math or writing assessment from a baseline of 67 percent in 2003 to 72

percent in 2004. Abundant research and school evidence suggest that setting such goals may

be the most significant act in the entire school improvement process, greatly increasing the

odds of success (Little, 1987; McGonagill, 1992; Rosenholtz, 1991; Schmoker, 1999, 2001).

If we take pains to keep the goals simple and to avoid setting too many of them, they focus the

attention and energies of everyone involved (Chang, Labovitz, & Rosansky, 1992; Drucker,

1992; Joyce, Wolf, & Calhoun, 1993). Such goals are quite different from the multiple, vague,

ambiguous goal statements that populate many school improvement plans.

Turning Weakness into Strength

After the teacher team has set a goal, it can turn to the next important question: Within the

identified subject or course, where do we need to direct our collective attention and expertise?

February 2003

http://pdonline.ascd.org/pd_online/contemp_s_lead/el200302_schmoker.html

11

In other words, where do the greatest number of students struggle or fail within the larger

domains? For example, in English and language arts, students may have scored low in writing

essays or in comprehending the main ideas in paragraphs. In mathematics, they may be weak

in measurement or in number sense.

Every state or standardized assessment provides data on areas of strength and weakness, at

least in certain core subjects. Data from district or school assessments, even gradebooks, can

meaningfully supplement the large-scale assessments. After team members identify strengths

and weaknesses, they can begin the real work of instructional improvement: the collaborative

effort to share, produce, test, and refine lessons and strategies targeted to areas of low

performance, where more effective instruction can make the greatest difference for students.

So What's the Problem?

Despite the importance of the two questions previously cited, practitioners can rarely answer

them. For years, during which dataand goals have been education by-words, I have asked

hundreds of teachers whether they know their goals for that academic year and which of the

subjects they teach have the lowest scores. The vast majority of teachers don't know. Even

fewer can answer the question: What are the low-scoring areas within a subject or course you

teach?

Nor could I. As a middle and high school English teacher, I hadn't the foggiest notion about

these datafrom state assessments or from my own records. This is the equivalent of a

mechanic not knowing which part of the car needs repair.

Why don't most schools provide teachers with data reports that address these two central

questions? Perhaps the straightforward improvement scheme described here seems too simple

to us, addicted as we are to elaborate, complex programs and plans (Schmoker, 2002; Stigler &

Hiebert, 1999).

Over-Analysis and Overload

The most important school improvement processes do not require sophisticated data analysis or

special expertise. Teachers themselves can easily learn to conduct the analyses that will have

the most significant impact on teaching and achievement.

The extended, district-level analyses and correlational studies some districts conduct can be

fascinating stuff; they can even reveal opportunities for improvement. But they can also divert

us from the primary purpose of analyzing data: improving instruction to achieve greater student

success. Over-analysis can contribute to overloadthe propensity to create long, detailed,

"comprehensive" improvement plans and documents that few read or remember. Because we

gather so much data and because they reveal so many opportunities for improvement, we set

too many goals and launch too many initiatives, overtaxing our teachers and our systems

(Fullan, 1996; Fullan & Stiegelbauer, 1991).

Formative Assessment Data and Short-Term Results

A simple template for a focused improvement plan with annual goals for improving students'

state assessment scores would go a long way toward solving the overload problem (Schmoker,

2001), and would enable teams of professional educators to establish their own improvement

priorities, simply and quickly, for the students they teach and for those in similar grades,

courses, or subject areas.

Using the goals that they have established, teachers can meet regularly to improve their

lessons and assess their progress using another important source: formative assessment data.

http://pdonline.ascd.org/pd_online/contemp_s_lead/el200302_schmoker.html

12

Gathered every few weeks or at each grading period, formative data enable the team to gauge

levels of success and to adjust their instructional efforts accordingly. Formative, collectively

administered assessments allow teams to capture and celebrate short-term results, which are

essential to success in any sphere (Collins, 2001; Kouzes & Posner, 1995; Schaffer, 1988).

Even conventional classroom assessment data work for us here, but with a twist. We don't just

record these data to assign grades each period; we now look at how many students succeeded

on that quiz, that interpretive paragraph, or that applied math assessment, and we ask

ourselves why. Teacher teams can now "assess to learn"to improve their instruction (Stiggins,

2002).

A legion of researchers from education and industry have demonstrated that instructional

improvement depends on just such simple, data-driven formatsteams identifying and

addressing areas of difficulty and then developing, critiquing, testing, and upgrading efforts in

light of ongoing results (Collins, 2001; Darling-Hammond, 1997; DuFour, 2002; Fullan, 2000;

Reeves, 2000; Schaffer, 1988; Senge, 1990; Wiggins, 1994). It all starts with the simplest kind

of data analysiswith the foundation we have when all teachers know their goals and the

specific areas where students most need help.

What About Other Data?

In right measure, other useful data can aid improvement. For instance, data on achievement

differences among socio-economic groups, on students reading below grade level, and on

teacher, student, and parent perceptions can all guide improvement.

But data analysis shouldn't result in overload and fragmentation; it shouldn't prevent teams of

teachers from setting and knowing their own goals and from staying focused on key areas for

improvement. Instead of overloading teachers, let's give them the data they need to conduct

powerful, focused analyses and to generate a sustained stream of results for students.

References

Chang, Y. S., Labovitz, G., & Rosansky, V. (1992). Making quality work: A leadership guide for

the results-driven manager. Essex Junction, VT: Omneo.

Collins, J. (2001, October). Good to great. Fast Company, 51, 90104.

Darling-Hammond, L. (1997). The right to learn: A blueprint for creating schools that work. New

York: Jossey-Bass.

Drucker, P. (1992). Managing for the future: The 1990s and beyond. New York: Truman Talley

Books.

DuFour, R. (2002). The learning-centered principal. Educational Leadership, 59(8), 1215.

Fullan, M. (1996). Turning systemic thinking on its head. Phi Delta Kappan, 77(6), 420423.

Fullan, M. (2000). The three stories of education reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(8), 581584.

Fullan, M., & Stiegelbauer, S. (1991). The new meaning of educational change. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Joyce, B., Wolf, J., & Calhoun, E. (1993). The self-renewing school. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (1995). The leadership challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Little, J. W. (1987). Teachers as colleagues. In V. Richardson-Koehler (Ed.), Educator's

handbook. White Plains, NY: Longman.

McGonagill, G. (1992). Overcoming barriers to educational restructuring: A call for "system

http://pdonline.ascd.org/pd_online/contemp_s_lead/el200302_schmoker.html

13

literacy." ERIC, ED 357512.

Reeves, D. (2000). Accountability in action. Denver, CO: Advanced Learning Press.

Rosenholtz, S. J. (1991). Teacher's workplace: The social organization of schools. New York:

Teachers College Press.

Schaffer, R. H. (1988). The breakthrough strategy: Using short-term successes to build the

high-performing organization. New York: Harper Business.

Schmoker, M. (1999). Results: The key to continuous school improvement (2nd ed). Alexandria,

VA: ASCD.

Schmoker, M. (2001). The results fieldbook: Practical strategies from dramatically improved

schools. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Schmoker, M. (2002). Up and away. Journal of Staff Development, 23(2), 1013.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New

York: Doubleday.

Stiggins, R. (2002). Assessment crisis: The absence of assessment FOR learning. Phi Delta

Kappan, 83(10), 758765.

Stigler, J. W., & Hiebert, J. (1999). The teaching gap: Best ideas from the world's teachers for

improving education in the classroom. New York: Free Press.

Wiggins, G. (1994). None of the above. The Executive Educator, 16(7), 1418.

Mike Schmoker is an educational speaker and consultant; @futureone.com. His most recent book is The

RESULTS Fieldbook: Practical Strategies from Dramatically Improved Schools (ASCD, 2001).

Copyright 2003 by Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD)

1703 N. Beauregard Street, Alexandria, VA 22311 USA 1-800-933-2723 1-703-578-9600

ASCD, All Rights Reserved Statement

3 Big Ideas and 4 Crucial Questions

14

Big Idea #1: Ensuring That Students Learn

Big Idea #2: A Culture of Collaboration

Big Idea #3: A Focus on Results

DuFour, Richard. (2005) What is a professional learning community? In

Barth, Roland et al. On common ground: The power of

professional learning communities. (pp. 31-43). Bloomington,

Indiana: Solution Tree.

Four Primary Questions

a. What do we want our students to learn?

i. Core curriculum emphasis

ii. Effecti ve collaboration

b. How do we know if they have learned?

i. Common Assessments

ii. Effecti ve collaboration

c. What do we do if they have not learned?

i. Systematic interventions

ii. Effecti ve collaboration

d. What are we doing to extend learning for

those students who have learned?

i. Systematic interventions for ALL levels

ii. Effecti ve collaboration

15

Creating SMART Goals

Letter

Major

Term

Minor Terms

S Specific Significant

[1]

, Stretching, Simple

M Measurable Meaningful

[1]

, Motivational

[1]

, Manageable

A Attainable

[2]

Appropriate, Achievable, Agreed

[3][4]

, Assignable

[5]

, Actionable,

Action-oriented

[1]

, Ambitious

[6]

R Relevant

Realistic

[5]

, Results/Results-focused/Results-oriented

[2]

,

Resourced

[7]

, Rewarding

[1]

T Time-bound

Time framed, Timed, Time-based, Timeboxed, Timely

[2][4]

,

Timebound, Time-Specific, Timetabled, Trackable, Tangible

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria

TAB 2

Teamwork Tool Kit tab goes here.

Annual I mpr ovement Goal s For 20__-20__

16

School:_________Team:________

GOAL 1: The percentage of our teams students who will be at or above

standard in

___________________________ will increase from:

_________________ at the end of 20___ (previous years

percentage/mean score) to

_________________% at the end of 20___as assessed by the

________________________ (State/District or School Assessment)

SPECIFIC, low-scoring skills/standard areas to improve (e.g.

Measurement, Compare & order fractions and decimals, Organization)

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

GOAL 2: The percentage of our teams students who will be at or above

standard in

____________________________ will increase from:

____________________% at the end of 20___ (precious years

percentage/mean score) to

__________________ % at the end of 20___ (the following years

percentage/mean score) as assessed by the

____________________ (State/District or School Assessment)

SPECIFIC skill areas to address/improve

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

17

Analyzing the PASS or HSAP School Demographic Report

(Based on work by LMS Leadership team)

Elementary and middle school AYP objectives for 2011-2012 are 79.4% for

English language arts and 79.0% for mathematics.

Note that the Not Met criterion for PASS was set at the same percent as

the Below Basic for PACT. That is the only score point at which scores from

the two testing programs are comparable.

High school AYP objectives for 2011-2012 increase to 90.3% for English

language arts and 90.0% for mathematics.

Run PASS school demographic reports or HSAP school demographic

reports in TestView.

Find the number of students tested for your subject and grade level. This

is listed as ALL STUDENTS.

Out of these students, what percent of male students scored Below Basic

(HSAP Level 1) or Not Met (PASS)?

How many actual students is this? (Take the percent, enter it as a decimal

and multiply by the actual number of students.)

How many African American students were tested on your grade level and

subject area?

What percent of these scored Not Met? (HSAP Level 1)

How many actual students is this?

How many students tested on your grade level and subject were identified

as having an IEP (This means ANY IEP)?

Out of these students, what percent scored Not Met? (HSAP Level 1)

How many actual students is this?

18

In order to meet AYP under current regulations in 2010-2011, a school

must have at least 79.4 % Met and Exemplary in ELA for PASS or at least

71.3% HSAP Level 3 and above for English language arts in the following

categories:

What are our percentages at

3 and 4 for HSAP or Met or Exemplary for PASS.

ALL STUDENTS _________%

WHITE _________%

AFRICAN AMERICAN _________%

ANY IEP _________%

TOTAL FREE/REDUCED MEALS _________%

(Note: Add other groups, as needed.)

Under the current regulations in order to meet AYP in 2010-2011, a school

must have at least or 79.0% for Math Met and Exemplary for PASS (or at

least 70.0% at HSAP Level 3 and above for mathematics) in the following

categories:

What are our percentages at

Proficient and Advanced in Math?

ALL STUDENTS _________%

WHITE _________%

AFRICAN AMERICAN _________%

ANY IEP _________%

TOTAL FREE/REDUCED MEALS _________%

(Note: Add other groups, as needed.)

Note that graduation rate will be evaluated in these categories, also.

19

Looking at these numbers, the subcategories seem to produce a small

number of actual students that are not making adequate progress in their

schooling.

List the factors that are not in our control, in relation to student

achievement. (Note: Although we acknowledge these issues, we must still

accept responsibility for helping all students achieve.)

List factors that are in our control, in relation to student achievement.

A lot of what we do in our classroom works for the majority of our students.

That is evident in our test scores for the general population. They look

great! However looking at more specific areas in the data, we find that

what we do for all students does not work for some students. Why do we

keep expecting these students to learn in a manner that has proven to be

ineffective for them? Is it productive to insist on teaching students in a

manner that we know has not been successful? What can we do differently

so that these few students do not fall through the cracks?

20

Guidelines for Interpreting MAP Reports

Virtual Comparison Group Reports by Class (available only after fall-to-spring

data are matched and computed for the academic year). These reports provide

the most accurate comparison of our students academic growth to the growth of

similar students in other schools that use MAP tests. Students who have fall and

spring test scores are matched by percent of students in the school who qualify

for free/reduced lunch, urban/rural classification, grade level, beginning RIT

score (within 1 point), and fall test dates (within 7 days). They are a powerful

indicator of the effectiveness of our instructional programs. Note: Administrators

have access to pivot table reports that can be disaggregated in a variety of ways.

1. The first page provides background information on the report.

2. The second page shows a plot of how growth for our students compared

with growth for the Virtual Comparison Group and where their

performance is with respect to Proficient and Advanced Cutpoints with the

Hybrid Success Target (which puts them on track to make a 3 on HSAP).

The Hybrid Success Target is the higher of two targets: either the median

virtual comparison group performance or the level of performance needed

to make adequate progress toward a score or 3 on HSAP at 10

th

grade.

3. The third page is a normalized score (Z-score) distribution for the class.

Students identified with Xs in the center section performed relatively close

to expectation based on the carefully matched data of the Virtual

Comparison Group reports. Green vertical bars indicate substantially high

growth. Red vertical bars indicate substantially low growth. It is not

uncommon to have one or two students in class of typical size who

show substantially low growth; often these will be recognized as

atypical performance attributable to a specific cause or as instances

where students who have not put forth serious effort on the test. If a

25% percent of the class shows substantially low growth, there is

reason to question the appropriateness of the instructional program

for those students. If there are any clusters of exceptionally high or

exceptionally low growth, then there may be a need to examine how

instruction is being differentiated.

4. Details are in the table on the fourth page.

5. The fifth page may be the most valuable for teachers because it provides

interpretations and suggestions and with student names when growth is

substantially above or below what would generally be expected.

Teacher Reports (available on line 24-48 hours after testing)

Use the following as some guiding questions for analysis:

1. Are the class mean and median about the same? If not, look for scores

that are outliers.

21

2. What is the standard deviation? (Standard deviations between 11-17

indicate a need for variety of grouping strategies. Standard deviations

larger than 17 indicate great diversity where differentiated instructional

strategies are especially necessary.)

3. What is the range of national percentiles (%ile Range) in the class?

4. In reading, what is the range of Lexile scores in the class? How does this

range compare to the Lexile level of available instructional materials?

5. Are there areas of strength and/or weakness, specifically Goal

Performance subscores that differ from the class average by 3 or more

points? (If scores indicate more than one area of need, concentrate on

the area that will be most likely to affect the students understanding of the

subject area.)

Class by RIT Reports (available on line)

1. How many 10-point RIT ranges are represented in the class distribution?

2. When you click on the subject area and display the distributions of Goal

Performance areas, what possibilities do you see for forming instructional

groups to address specific needs?

3. Based on DesCartes objectives, what additional assessments are needed

to determine specific instructional needs for your students within given RIT

ranges?

Spring Achievement Status & Growth (ASG) Reports (must be ordered after

district window closes)

1. What percent of students met or exceeded their growth targets? (The

districts minimum expectation is average performance has increased from

50% for this statistic to 53% to maintain alignment with increases in

national performance data. Teams may want to set higher goals.)

2. What is the overall percent of targets met? (The districts minimum

expectation is average performance, which is generally 100% for this

statistic. Teams may want to set higher goals.)

3. Which students made gains that exceeded their targets? (Congratulate

them!)

22

4. Which students have scores that are more than one Growth Standard

Error below their target scores? (Were they focused on the assessment?

What might motivate them to take greater interest in the subject?)

NOTE: The percents in ASG Reports will differ from the percents in the Virtual

Comparison Group Reports because the achievement targets for Virtual

Comparison Group Reports are more closely matched to the characteristics of

the students in our classes.

Dynamic Reports

Projections from MAP to PASS are available online. The projection is based on

a 50% probability of scoring MET on PASS. To guarantee that a student would

score at the MET level, a students score would need to be considerably higher

than the minimum cut score.

23

Guiding Questions for Analysis MAP Growth

Getting Ready

For this exercise you will need four items:

1. The School Overview Report from Dynamic Reports for Fall-Spring (See instructions

below).

2. The School Overview Report from Dynamic Reports for Spring-Spring (See instructions

below).

Instructions for accessing School Overview Reports

1. Open a web browser and navigate to https://reports.nwea.org.

2. Log in to the NWEA reports site.

3. From the links on the left hand side of the page, select Dynamic Reports.

4. Click the button labeled Dynamic Reports.

5. The default screen will be your School Overview for FallXX-SpringYY (Where XX

and YY are school years).

6. To access this same report for SpringXX-SpringYY, click the Run this report for a

different term link on the top right side of the report.

General Notes

These guiding questions are designed as an initial analysis piece for school administrators

and instructional leaders. This analysis will show you a broad picture of how your school is

performing at both the school and grade level. You will also examine some student level data.

However, this exercise is merely a starting point. Once you have completed this exercise, it is

important that you extend your inquiry to the classroom and student level in order to best

improve instruction. Virtual comparison group (VCG) reports will be coming out after Spring

testing. These reports will help you to further analyze growth in your school relative to similar

students from around the nation.

24

Guiding Questions for Analysis

1. Using the School Overview Reports, carefully consider and answer the following

questions for each subject area.

a.

b. The 2009 NWEA School Growth Study indicated that average percent meeting

target for schools around the nation had risen, as teachers have learned to focus

their teaching on standards. The spring-to-spring percents meeting target varied

by subject and grade level, from 49% in fifth-grade mathematics to 56% in

second- and fourth- grade reading. Overall the data indicated that the average

percent meeting published spring-to-spring targets was about 53%. Fall-to-spring

results were several percent higher. Since average performance for schools all

over the nation has improved improving, our expectations are that we our

instructional success rate would be at least up to the national average, or 53%.

i. In Lexington One, we can celebrate the fact that our instruction has

improved to the point that almost 60% of students meet or exceed

published target growth for fall -to-spring virtual comparison group

(VCG) scores.

ii. How does your school percent meeting published target growth compare

with the districts VCG results?

c. Consider the Student Growth Summary reports for your school that administrators

order online via the www.nwea.org Web site. Those are calculated with targets

that are similar, but not always identical to the ASG targets. As long as we have a

MAP contract, administrators can order both fall-to-spring and spring-to-spring

reports, as well as all reports for previous years. What was the difference between

the percent of students in your school meeting growth targets in the fall-to-spring

report and the spring-to-spring report? (Remember that spring scores are a better

measure of student growth for grades when they are available because they are

not affected by summer loss or differing levels of motivation in the fall.) If your

fall percents are more than 5 percentage points lower than your spring percents,

talk about what might be happening to cause such a difference?

2. Using the School Overview reports from NWEAs Dynamic Reports, carefully consider

and answer the following questions for each subject area.

a. Take a look at your yellow, orange and red boxes. These are the students, based

on MAP, who are in need of intervention. Students in the red and orange boxes

are not meeting their growth targets. Students in the yellow box need to do more

than meet their growth targets to progress to the Met level on PASS. Click on the

boxes to drill down and see individual students. Based on the growth index (the

distance in RIT points from the students growth target), how far are these

students from meeting the target? What is their proficiency probability? Do any

patterns exist within these groups of students ( grade level, subject area, teacher)?

What are your plans for identifying and addressing the needs of these students?

Could there be implications for professional development plans?

b. Do any patterns exist for the students in your green box? What are your plans for

ensuring that these students continue to grow and achieve at high levels?

c. The expectation of 53% meeting target is a minimum expectation. If your school

had grade levels and subject areas that did not meet the minimum expectation,

consider these questions carefully:

25

i. What do you as the school administrative team know about instruction in

those grade levels and subject areas from your classroom observations this

year?

ii. What have the teachers shared from their collaborative planning, common

assessments, and data analysis?

iii. What have you learned from conferencing with those teachers?

iv. What is your plan for supporting and supervising teachers in those grade

levels and subject areas next year?

d. Looking ahead to next year, how would projected proficiency for your school

compare to the 2011-2012 AYP requirements for percent meeting proficiency

(79% for math and 79.4% for reading)?

26

Testing Information from the SCDE Office of Assessment

The South Carolina Department of Education provides Web resources that

include information about the kinds and proportions of questions on its

accountability tests.

Despite widespread misconceptions about what can be assessed with multiple-

choice items, the South Carolina tests include many items that assess higher

order thinking skills, and the standards for proficiency are challenging. Links to

these resources are printed below.

HSAP Blueprints:

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/offices/assessment/programs/hsap/blueprints.html

HSAP Rubrics:

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/offices/assessment/programs/hsap/hsaprubrics.html

HSAP Score Report Users Guide: (No 2011 Guide has been posted as of J uly

2011;however, changes would be minimal).

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/ac/Assessment/documents/2010_HSAP_UsersGuide.pdf

EOCEP Curriculum Standards:

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/offices/assessment/programs/endofcourse/standards.html

EOCEP Blueprints:

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/offices/assessment/programs/endofcourse/blueprints.html

PASS

Curriculum standards and test blueprints are located at the subject area links

under the heading, Where can I find more information and item samples for

each PASS test? at the following address:

http://ed.sc.gov/agency/ac/Assessment/PASS.html

Extended Response Scoring Rubric Grades 3 8 Updated 10/23/2008

SCORE 4

3 2 1

CONTENT /

DEVELOPMENT

Presents a clear central idea

about the topic

Fully develops the central idea

with specific, relevant details

Sustains focus on central idea

throughout the writing

Presents a central idea about

the topic

Develops the central idea but

details are general, or the

elaboration may be uneven

Focus may shift slightly, but is

generally sustained

Central idea may be unclear

Details need elaboration to

clarify the central idea

Focus may shift or be lost

causing confusion for the

reader

There is no clear central idea

Details are sparse and/ or

confusing

There is no sense of focus

ORGANIZATION

Has an effective introduction,

body, and conclusion

Provides a smooth

progression of ideas by using

transitional devices

throughout the writing

Has an introduction, body,

and conclusion

Provides a logical progression

of ideas throughout the

writing

Attempts an introduction,

body, and conclusion;

however, one or more of

these components could be

weak or ineffective

Provides a simplistic,

repetitious, or somewhat

random progression of ideas

throughout the writing

Attempts an introduction,

body, and conclusion;

however, one or more of these

components could be absent or

confusing

Presents information in a

random or illogical order

throughout the writing

VOICE

Uses precise and/or vivid

vocabulary appropriate for the

topic

Phrasing is effective, not

predictable or obvious

Varies sentence structure to

promote rhythmic reading

Shows strong awareness of

audience and task; tone is

consistent and appropriate

Uses both general and precise

vocabulary

Phrasing may not be effective,

and may be predictable or

obvious

Some sentence variety results

in reading that is somewhat

rhythmic; may be mechanical

Shows awareness of audience

and task; tone is appropriate

Uses simple vocabulary

Phrasing is repetitive or

confusing

Shows little or no sentence

variety; reading is monotonous

Shows little or no awareness of

audience and task; tone may

be inappropriate

CONVENTIONS

Provides evidence of a

consistent and strong

command of grade-level

conventions (grammar,

capitalization, punctuation,

and spelling)

Provides evidence of an

adequate command of grade-

level conventions (grammar,

capitalization, punctuation,

and spelling)

Provides evidence of a limited

command of grade-level

conventions (grammar,

capitalization, punctuation,

and spelling)

Provides little or no evidence of

having a command of grade-

level conventions (grammar,

capitalization, punctuation, and

spelling)

NOTE: This rubric MUST be used in conjunction with specific grade- level skills as outlined in the Composite Matrix for the Conventions of

Grammar, Mechanics of Editing, Revision and Organizational Strategies, and Writing Products (Appendix B of ELA Standards, 2008).

Blank B

Off Topic OT

Insufficient IS

Unreadable UR

Not Original NO

27

HSAP EXTENDED RESPONSE SCORING RUBRIC

28

SCORE CONTENT/DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION VOICE CONVENTIONS

4

Presents a clear central idea about the

topic

Fully develops the central idea with

specific, relevant details

Sustains focus on central idea

throughout the writing

Has a clear introduction, body, and

conclusion.

Provides a smooth progression of

ideas throughout the writing.

Minor errors in standard written English

may be present.

3

Presents a central idea about the topic

Develops the central idea but details

are general, or the elaboration may be

uneven

Focus may shift slightly, but is

generally sustained

Has an introduction, body, and

conclusion.

Provides a logical progression of

ideas throughout the writing.

Uses precise and/or vivid

vocabulary appropriate for the

topic

Phrasing is effective, not

predictable or obvious

Varies sentence structure to

promote rhythmic reading

Strongly aware of audience and

task; tone is consistent and

appropriate

Errors in standard written English may be

present; however, these errors do not

interfere with the writers meaning.

2

Central idea may be unclear

Details may be sparse; more

information is needed to clarify the

central idea

Focus may shift or be lost causing

confusion for the reader

Attempts an introduction, body,

and conclusion; however, one or

more of these components could be

weak or ineffective.

Provides a simplistic, repetitious,

or somewhat random progression

of ideas throughout the writing.

Uses both general and precise

vocabulary

Phrasing may not be effective,

and may be predictable or

obvious

Some sentence variety results in

reading that is somewhat

rhythmic; may be mechanical

Aware of audience and task; tone

is appropriate

A pattern of errors in more than one

category (e.g., capitalization, spelling,

punctuation, sentence formation) of

standard written English is present; these

errors interfere somewhat with the writers

meaning.

1

There is no clear central idea

Details are absent or confusing

There is no sense of focus

Attempts an introduction, body,

and conclusion; however, one or

more of these components could be

absent or confusing.

Presents information in a random

or illogical order throughout the

writing.

Uses simple vocabulary

Phrasing repetitive or confusing

There is little sentence variety;

reading is monotonous

There is little awareness of

audience and task; tone may be

inappropriate

Frequent and serious errors in more than

one category (e.g., capitalization, spelling,

punctuation, sentence formation) of

standard written English are present; these

errors severely interfere with the writers

meaning.

B Blank

Off Topic

Insufficient amount of original writing to evaluate

Unreadable or illegible

OT

IS

UR

For the purposes of scoring Conventions, interference is defined as that which would impede meaning for a reader other than an educator or professional reader.

29

Facilitator

A facilitator skillfully helps a group of people understand their common

objectives and plan to achieve them without personally taking any side of

the argument. The facilitator assists the group in achieving a consensus

on any disagreements that preexist or emerge in the meeting to create

strong basis for future action.

The role of a facilitator

Some of the things facilitators do to assist a meeting:

Helping participants show up prepared to contribute

Codifying the purpose, scope, and deliverables of the meeting or

workshop

Keeping the group on track to achieve its goals in the time

allotted

Either providing the group or helping the group decide what

ground rules it should follow and reminding them of these when

they are not followed

Reminding the group of the objectives or deliverables of the

meeting or session

Setting up a safe environment where members feel comfortable

contributing ideas

Guiding the group through processes designed to help them

listen to each other and create solutions together

Asking open-ended questions that stimulate thinking

Ensuring the group doesn't settle for the first thing that they can

agree on because they find it painful to go on disagreeing with

each other

Offering opportunities for less forceful members to come forward

with contributions

Ensuring that actions agreed upon by the group are assigned to

individuals

Team Roles

30

Timekeeper

A timekeeper is someone who skillfully keeps the meeting on a schedule.

Effective, time-efficient meetings are fast paced and productive. The

timekeeper moves the group through the different parts of the meeting.

The chief challenge is to keep members on track with clear concise

statements lasting no more that 20 seconds during the brain storming

section. Below is a suggested guideline of each part of the meeting.

Recorder

The recorder writes all ideas where participants can see, possibly on a flip

chart, chalkboard, smart board, or white board. If using a flipchart, post

(rather than flip back) each page as it is completed. The recorder may

question participants for clarity of submission. Actions agreed upon by the

group (the assessment and lesson plan) are recorded for all to see and

are assigned to individuals. The recorder also completes the Team

Learning Log or sees that it is completed by another team member.

Brainstorming Guidelines

Schmoker The Results Field Book pg. 136 31

The purpose of brainstorming is to produce as many good ideas

as possible in a fast-paced, positive setting. This step in a

focused improvement meeting includes the following:

Assign a recorder to ensure that the group keeps accurate notes of each

idea or strategy.

State the purpose or desired result of the team meeting, preferably in

writing.

Write each idea on a flip chart, chalkboard, or white board. If using a

flipchart, post rather than flip back, each page as it is completed.

Offer each person in the group in consecutive order the opportunity to

contribute one idea or strategy.

Give team members the option to pass when it is their turn to

contribute.

Keep each persons remarks as succinct as possible by limiting

comments to 20 seconds or less.

Do not criticize or discuss of ideas or strategies at this time.

Expect to piggyback or build on each others ideas to generate the

best strategies.

32

Warm and Cool Feedback

There are two types of feedback in this process. The first one is Warm

feedback. This feedback is termed warm because it is supportive in nature.

Warm feedback may include comments about how the work presented seems to

meet the desired goals and generally consists of supportive statements.

The second one is Cool feedback. Cool feedback is more critical. It may

consist of concise essential questions that are both supportive and challenging.

(i.e. Where are the gaps?; What are the problems here?) Teachers who have

experience using the Tuning Protocol suggest that softened statements for

Cool feedback are more comfortable for teachers who have agreed to take the

risk of presenting their work. For example, I wonder what would happen if

you tried this, is more acceptable than, I think you should have or ,Why

didnt you.?

Rewards, Recognition, and Celebration

Rewards, recognition, and celebration are important motivators. These three

things are indispensable elements of effective leadership. As we practice

collaborative planning with common formative assessments, we have to

celebrate small achievements. Typically teachers receive little recognition and

praise. When data from common assessments show even small gains, we need

to recognize and celebrate that. Here are a few ideas for rewards, recognition,

and celebration:

Charts posted in a prominent place

Announcements at faculty meetings

Newsletter articles

Thank-you notes

A free meal, (even at the school cafeteria)

Goofy grab bag gifts

Tickets to a movie

Book store gift certificate

Car wash passes purchased at a local car wash

The goal is to have staff members share an enthusiasm and focus that simply

did not exist in the school before, and regularly celebrating small achievements

helps build and maintain momentum.

Collaborative Planning Lesson Study Protocol

33

Preparation

The group leader must establish norms, meeting guidelines, and

protocols. This time is for collaborative planning, and independent work is

not permitted. The smallest allowable group is two people. In the

beginning, the grade level leader or department chair will organize the

planning. After the group norms are established, all of the roles in the

collaborative group can rotate. Planning for a larger group can rotate by

subject area, with all teachers collaborating in lesson and assessment

design, even though they are not currently teaching the subject under

consideration.

Prepare an agenda and decide on team roles (e.g., timekeeper, facilitator,

recorder). Inform appropriate people (such as department chairs, grade-

level leaders, school administrators, district subject level coordinators) of

the schedule. They may need to know what groups will be meeting and

what focus is planned.

Keep to the agenda, and eliminate announcements that are not critical to

the process.

Establish time limits for discussion. Teams can probably complete plans

and draft common assessments for two lessons in a two-hour session. A

time limit of one hour for each lesson will help to keep the process

focused.

Protocol

1. Follow Up: Begin with follow-up from the last collaborative planning

meeting. Engage members in a concise discussion of what worked, what

did not work, and how strategies can be refined. This can be done in 5-10

minutes.

Complete steps 2-4 in approximately 20 minutes. (The process will move

faster with practice.) Groups should be able to complete the process for

one lesson and assessment in about an hour. The goal for a two-hour

session would typically be to design two lessons with accompanying

assessments.

2. Chief Challenges: Identify a standard where your students need to

improve their skills (a relative weakness) that you plan to teach in the next

week or so. This ought to reflect the most urgent instructional concern,

problem, or obstacle to progress.

Teachers should use data that are relevant for their own students ,

including, but not limited to, state-mandated assessments (HSAP, PACT,

Collaborative Planning Lesson Study Protocol

34

EOCEP, revised SCRAPI for 2006-2007), other standardized

assessments (MAP, Explore, Plan, text levels, WorkKeys), teacher-made

assessments, IEPs, and grades. With practice, this can be done in 3-5

minutes.

3. Rough out an assessment for the lesson you plan to teach. Identify

what goes into an assessment of the standard by brainstorming the skills.

From the brainstorm, identify the crucial skills needed to master the

standard. The assessment doesn't have to be polished at this point, but

the design should be specific enough to show exactly what students will

have to do to demonstrate that they have mastered the standard. Be sure

you require students to do more than retrieve factual information. Make

sure they will be required to demonstrate higher-order cognitive

processes, such as application, understanding, analysis, and synthesis.

4. Plan a lesson designed to help as many students as possible succeed

on the assessment. Sketch the sequence and content of the lesson.

When applicable, the design phase may incorporate review of new

instructional materials.

5. Pretend you've taught the lesson and that it didn't work quite as well as

you'd have liked. Refine the assessment and the lesson.

6. Arrange to share copies of the lesson plan and the assessment for all

teachers in the target group to use. Agree on who will produce finished

copies of the assessment and lesson plan for team members and when

the lesson will be taught.

7. Before the next planning session, team members teach the lesson to

their classes and use the common assessment theyve designed to

determine what students have learned. Teachers summarize results for

their own classes. They look at more than grades. They reflect on

patterns. What concepts/skills did students master? What concepts/skills

were difficult for many students? What needs reteaching or further

development? Where do they need to focus next?

8. At the beginning of the next collaborative planning session (or sooner,

if there is opportunity), teachers compare results and analyses with those

of the other teachers in their group.

Adapted from Results Now, pp. 111-112.

Collaborative Planning Lesson Study Protocol

35

Accountability

Groups will keep brief minutes of who was present/absent and the topics

that were considered. They may either describe or attach lesson plans

and common assessments. A basic format for minutes is included in this

guide.

Administrators are expected to conduct walk-throughs on the collaborative

planning sessions. Expect them to stop by and listen for a few minutes. If

some groups need to see the process modeled and/or to keep the

momentum going, administrators may ask teachers to present the

lessons, the common assessments they've designed, and their analysis of

the results to other groups within the faculty.

The Tuning Protocol: A Process for Reflection on Teacher and Student Work

36

From the Coalition of Essential Schools

Authors: David Allen, Joe McDonald

The "tuning protocol" was developed by David Allen and Joe McDonald at the

Coalition of Essential Schools primarily for use in looking closely at student

exhibitions. Also, it is often used by teachers to look at the effectiveness of lessons.

In the outline below, unless otherwise noted, time allotments indicated are the

suggested minimum for each task.

I. Introduction [10 minutes]. Facilitator briefly introduces protocol goals, norms,

and agenda. Participants briefly introduce themselves.

II. Teacher Presentation [20 minutes]. Presenter describes the context for student

work (its vision, coaching, scoring rubric, etc.) and presents samples of student

work (such as photo- copied pieces of written work or video tapes of an exhibition).

III. Clarifying Questi ons [15 minutes maximum]. Facilitator judges if questions

more properly belong as warm or cool feedback than as clarifiers.

IV. Pause to reflect on warm and cool feedback [2-3 minutes maximum].

Participants make note of "warm," supportive feedback and 'cool," more distanced

comments

(generally no more than one of each).

V. Warm and Cool Feedback [15 minutes]. Participants among themselves share

responses to the work and its context; teacher-presenter is silent. Facilitator may

lend focus by reminding participants of an area of emphasis supplied by teacher-

presenter.

VI. Reflection/ Response [15 minutes]. Teacher-presenter reflects on and

responds to those comments or questions he or she chooses to. Participants are

silent. Facilitator may clarify or lend focus.

VII. Debrief [10 minutes]. Beginning with the teacher-presenter

("How did the protocol experience compare with what you expected?"), the group

discusses any frustrations, misunderstandings, or positive reactions participants

have experienced. More general discussion of the tuning protocol may develop.

Guidelines for Facilitators

1. Be assertive about keeping time. A protocol that doesn't allow for all the

components will do a disservice to the presenter, the work presented, and the

participants' understanding of the process. Don't let one participant monopolize.

The Tuning Protocol: A Process for Reflection on Teacher and Student Work

37

2. Be protective of teacher-presenters. By making their work more public, teachers

are exposing themselves to kinds of critiques they may not be used to.

Inappropriate comments or questions should be recast or withdrawn. Try to

determine just how "tough" your presenter wants the feedback to be.

3. Be provocative of substantive discourse. Many presenters may be used to

blanket praise. Without thoughtful but probing "cool" questions and comments, they

won't benefit from the tuning protocol experience. Presenters often say they'd have

liked more cool feedback.

Norms for Participants

1. Be respectful of teacher-presenters. By making their work more public, teachers

are exposing themselves to kinds of critiques they may not be used to.

Inappropriate comments or questions should be recast or withdrawn.

2. Contribute to substantive discourse. Without thoughtful but probing "cool"

questions and comments, presenters won't benefit from the tuning protocol

experience.

3. Be appreciative of the facilitator's role. particularly in regard to following the

norms and keeping time. A tuning protocol that doesn't allow for all components

(presentation, feedback, response, debrief) to be enacted properly will do a

disservice both to the teacher-presenters and to the participants.

Allen, D. and McDonald, J. (2003). The tuning protocol: A process for reflection on

teacher and student work. Retrieved August 4, 2006 from Coalition of

Essential Schools National Web site:

http://www.essentialschools.org/cs/resources/view/ces_res/54

The Consultancy Protocol

38

The Consultancy Protocol

(Also called the California Protocol or Reflecting with Critical Friends)

Many teachers in California's Coalition member schools routinely use the tuning

protocol to surface issues arising from close examination of student work. But the

state's Restructuring Initiative, which funds some 150 schools attempting whole-

school reforms, has also adapted and expanded the protocol for a new purpose to

examine how such issues relate to the larger school organization and its aims, and

to summarize and assess its progress. Instead of having teachers present student

work, the California Protocol has a school's "analysis team" work through an

important question (possibly using artifacts from their work) in the presence of a

group of reflectors, as follows:

The moderator welcomes participants and reviews the purpose, roles, and

guidelines for the Protocol [5 minutes]

Anal ysis

1. Analysis Team provides an introduction including an essential question that will

be the focus of the analysis. [5 minutes]

2. Reflectors ask brief questions for clarification, and the Analysis Team responds

with succinct information. [5 minutes]

3. Analysis Team gives its analysis. [25 minutes]

4. Reflectors ask brief questions for clarification, and the Analysis Team responds

with succinct clarifying information about the Analysis. [5 minutes)

Feedback

1. Reflectors form groups of 4 to 6 to provide feedback; one member of each is

chosen to chart warm, cool, and hard feedback. The Reflector Groups summarize

their feedback as concise essential questions (cool and hard feedback) and

supportive statements (warm feedback). Each group posts the chart pages as they

are completed so Analysis Team Members can see them. [15 minutes]

2. The Analysis Team observes and listens in on the feedback process. They may

also wish to caucus informally as the feedback emerges and discuss which points

to pursue in the Reflection time to follow.

3. Each Reflector Group shares one or two supportive statements and essential

questions that push further thought. [5 minutes]

Team Reflection and Planning

The Analysis Team engages in reflection, planning, and discussion with one