Tax Rev

Diunggah oleh

'Xanne SkmvJudul Asli

Hak Cipta

Format Tersedia

Bagikan dokumen Ini

Apakah menurut Anda dokumen ini bermanfaat?

Apakah konten ini tidak pantas?

Laporkan Dokumen IniHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

Tax Rev

Diunggah oleh

'Xanne SkmvHak Cipta:

Format Tersedia

1

1. CIR v ALGUE

DIGEST1

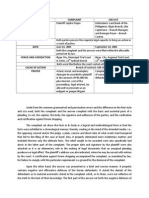

CIR vs. Algue Inc.

Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. Algue Inc.

GR No. L-28896 | Feb. 17, 1988

Facts:

Algue Inc. is a domestic corp engaged in engineering, construction and other

allied activities

On Jan. 14, 1965, the corp received a letter from the CIR regarding its

delinquency income taxes from 1958-1959, amtg to P83,183.85

A letter of protest or reconsideration was filed by Algue Inc on Jan 18

On March 12, a warrant of distraint and levy was presented to Algue Inc. thru its

counsel, Atty. Guevara, who refused to receive it on the ground of the pending

protest

Since the protest was not found on the records, a file copy from the corp was

produced and given to BIR Agent Reyes, who deferred service of the warrant

On April 7, Atty. Guevara was informed that the BIR was not taking any action on

the protest and it was only then that he accepted the warrant of distraint and levy

earlier sought to be served

On April 23, Algue filed a petition for review of the decision of the CIR with the

Court of Tax Appeals

CIR contentions:

- the claimed deduction of P75,000.00 was properly disallowed because it was

not an ordinary reasonable or necessary business expense

- payments are fictitious because most of the payees are members of the same

family in control of Algue and that there is not enough substantiation of such

payments

CTA: 75K had been legitimately paid by Algue Inc. for actual services rendered

in the form of promotional fees. These were collected by the Payees for their work

in the creation of the Vegetable Oil Investment Corporation of the Philippines and

its subsequent purchase of the properties of the Philippine Sugar Estate

Development Company.

Issue:

W/N the Collector of Internal Revenue correctly disallowed the P75,000.00

deduction claimed by Algue as legitimate business expenses in its income tax

returns

Ruling:

Taxes are the lifeblood of the government and so should be collected without

unnecessary hindrance, made in accordance with law.

RA 1125: the appeal may be made within thirty days after receipt of the decision

or ruling challenged

During the intervening period, the warrant was premature and could therefore

not be served.

Originally, CIR claimed that the 75K promotional fees to be personal holding

company income, but later on conformed to the decision of CTA

There is no dispute that the payees duly reported their respective shares of the

fees in their income tax returns and paid the corresponding taxes thereon. CTA

also found, after examining the evidence, that no distribution of dividends was

involved

CIR suggests a tax dodge, an attempt to evade a legitimate assessment by

involving an imaginary deduction

Algue Inc. was a family corporation where strict business procedures were not

applied and immediate issuance of receipts was not required. at the end of the

year, when the books were to be closed, each payee made an accounting of all

of the fees received by him or her, to make up the total of P75,000.00. This

arrangement was understandable in view of the close relationship among the

persons in the family corporation

The amount of the promotional fees was not excessive. The total commission

paid by the Philippine Sugar Estate Development Co. to Algue Inc. was P125K.

After deducting the said fees, Algue still had a balance of P50,000.00 as clear

profit from the transaction. The amount of P75,000.00 was 60% of the total

commission. This was a reasonable proportion, considering that it was the payees

who did practically everything, from the formation of the Vegetable Oil

Investment Corporation to the actual purchase by it of the Sugar Estate

properties.

Sec. 30 of the Tax Code: allowed deductions in the net income Expenses - All

the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in

carrying on any trade or business, including a reasonable allowance for salaries or

other compensation for personal services actually rendered xxx

the burden is on the taxpayer to prove the validity of the claimed deduction

In this case, Algue Inc. has proved that the payment of the fees was necessary

and reasonable in the light of the efforts exerted by the payees in inducing

investors and prominent businessmen to venture in an experimental enterprise and

involve themselves in a new business requiring millions of pesos.

2

Taxes are what we pay for civilization society. Without taxes, the government

would be paralyzed for lack of the motive power to activate and operate it.

Hence, despite the natural reluctance to surrender part of one's hard earned

income to the taxing authorities, every person who is able to must contribute his

share in the running of the government. The government for its part, is expected to

respond in the form of tangible and intangible benefits intended to improve the

lives of the people and enhance their moral and material values

Taxation must be exercised reasonably and in accordance with the prescribed

procedure. If it is not, then the taxpayer has a right to complain and the courts will

then come to his succor

Algue Inc.s appeal from the decision of the CIR was filed on time with the CTA in

accordance with Rep. Act No. 1125. And we also find that the claimed deduction

by Algue Inc. was permitted under the Internal Revenue Code and should

therefore not have been disallowed by the CIR

DIGEST2

COMMISSIONER v. ALGUE, INC.

GR No. L-28896, February 17, 1988

158 SCRA 9

FACTS:

Private respondent corporation Algue Inc. filed its income tax returns for 1958 and

1959showing deductions, for promotional fees paid, from their gross income, thus

lowering their taxable income. The BIR assessed Algue based on such deductions

contending that the claimed deduction is disallowed because it was not an

ordinary, reasonable and necessary expense.

ISSUE:

Should an uncommon business expense be disallowed as a proper deduction in

computation of income taxes, corollary to the doctrine that taxes are the

lifeblood of the government?

HELD:

No. Private respondent has proved that the payment of the fees was necessary

and reasonable in the light of the efforts exerted by the payees in inducing

investors and prominent businessmen to venture in an xperimental enterprise and

involve themselves in a new business requiring millions of pesos. This was no mean

feat and should be, as it was, sufficiently recompensed.

It is well-settled that taxes are the lifeblood of the government and so should be

collected without unnecessary hindrance On the other hand, such collection

should be made in accordance with law as any arbitrariness will negate the very

reason for government itself. It is therefore necessary to reconcile the apparently

conflicting interests of the authorities and the taxpayers so that the real purpose of

taxation, which is the promotion of the common good, may be achieved.

But even as we concede the inevitability and indispensability of taxation, it is a

requirement in all democratic regimes that it be exercised reasonably and in

accordance with the prescribed procedure. If it is not, then the taxpayer has a

right to complain and the courts will then come to his succor. For all the awesome

power of the tax collector, he may still be stopped in his tracks if the taxpayer can

demonstrate, as it has here, that the law has not been observed.

DIGEST3

G.R. No. L-28896 February 17, 1988

COMMISSIONER OF INTERNAL REVENUE, petitioner,

vs.

ALGUE, INC., and THE COURT OF TAX APPEALS, respondents.

FACTS:

The Philippine Sugar Estate Development Company had earlier appointed Algue

as its agent, authorizing it to sell its land, factories and oil manufacturing process.

Pursuant to such authority, Alberto Guevara, Jr., Eduardo Guevara, Isabel

Guevara, Edith, O'Farell, and Pablo Sanchez, worked for the formation of the

Vegetable Oil Investment Corporation, inducing other persons to invest in it.

Ultimately, after its incorporation largely through the promotion of the said

persons, this new corporation purchased the PSEDC properties. For this sale, Algue

received as agent a commission of P126, 000.00, and it was from this commission

that the P75, 000.00 promotional fees were paid to the a forenamed individuals.

The petitioner contends that the claimed deduction of P75, 000.00 was properly

disallowed because it was not an ordinary reasonable or necessary business

expense. The Court of Tax Appeals had seen it differently. Agreeing with Algue, it

held that the said amount had been legitimately paid by the private respondent

for actual services rendered. The payment was in the form of promotional fees.

ISSUE:

Whether or not the Collector of Internal Revenue correctly disallowed the P75,

000.00 deduction claimed by private respondent Algue as legitimate business

expenses in its income tax returns.

3

RULING:

The Supreme Court agrees with the respondent court that the amount of the

promotional fees was not excessive. The amount of P75,000.00 was 60% of the

total commission. This was a reasonable proportion, considering that it was the

payees who did practically everything, from the formation of the Vegetable Oil

Investment Corporation to the actual purchase by it of the Sugar Estate

properties.

It is said that taxes are what we pay for civilization society. Without taxes, the

government would be paralyzed for lack of the motive power to activate and

operate it. Hence, despite the natural reluctance to surrender part of one's hard

earned income to the taxing authorities, every person who is able to must

contribute his share in the running of the government.

DIGEST4

Commissioner vs. AlgueGRL-28890, 17 February 1988First Division, Cruz (J); 4 concur

Facts:

The Philippine Sugar Estate Development Company (PSEDC) appointed Algue

Inc. as its agent,authorizing it to sell its land, factories, and oil manufacturing

process. The Vegetable Oil InvestmentCorporation (VOICP) purchased PSEDC

properties. For the sale, Algue received a commission of P125,000 and it was from

this commission that it paid Guevara, et. al. organizers of the VOICP, P75,000in

promotional fees. In 1965, Algue received an assessment from the Commissioner

of Internal Revenuein the amount of P83,183.85 as delinquency income tax for

years 1958 amd 1959. Algue filed a protestor request for reconsideration which

was not acted upon by the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR). Thecounsel for Algue

had to accept the warrant of distrant and levy. Algue, however, filed a petition

forreview with the Coourt of Tax Appeals.

Issue:

Whether the assessment was reasonable.

Held:

Taxes are the lifeblood of the government and so should be collected without

unnecessaryhindrance. Every person who is able to pay must contribute his share

in the running of the government.The Government, for his part, is expected to

respond in the form of tangible and intangible benefitsintended to improve the

lives of the people and enhance their moral and material values. This

symbioticrelationship is the rationale of taxation and should dispel the erroneous

notion that is an arbitrarymethod of exaction by those in the seat of power. Tax

collection, however, should be made inaccordance with law as any arbitrariness

will negate the very reason for government itself. For all theawesome power of the

tax collector, he may still be stopped in his tracks if the taxpayer candemonstrate

that the law has not been observed. Herein, the claimed deduction (pursuant to

Section 30[a] [1] of the Tax Code and Section 70 [1] of Revenue Regulation 2: as

to compensation for personalservices) had been legitimately by Algue Inc. It has

further proven that the payment of fees wasreasonable and necessary in light of

the efforts exerted by the payees in inducing investors (in VOICP) toinvolve

themselves in an experimental enterprise or a business requiring millions of pesos.

Theassessment was not reasonable.

4

2.

PEPSICOLA V. MUN. OF TANAUAN

DIGEST 1

69 SCRA 460 Taxation Delegation to Local Governments Double Taxation

Pepsi Cola has a bottling plant in the Municipality of Tanauan, Leyte. In

September 1962, the Municipality approved Ordinance No. 23 which levies and

collects from soft drinks producers and manufacturers a tai of one-sixteenth

(1/16) of a centavo for every bottle of soft drink corked.

In December 1962, the Municipality also approved Ordinance No. 27 which levies

and collects on soft drinks produced or manufactured within the territorial

jurisdiction of this municipality a tax of one centavo P0.01) on each gallon of

volume capacity.

Pepsi Cola assailed the validity of the ordinances as it alleged that they constitute

double taxation in two instances: a) double taxation because Ordinance No. 27

covers the same subject matter and impose practically the same tax rate as with

Ordinance No. 23, b) double taxation because the two ordinances impose

percentage or specific taxes.

Pepsi Cola also questions the constitutionality of Republic Act 2264 which allows

for the delegation of taxing powers to local government units; that allowing local

governments to tax companies like Pepsi Cola is confiscatory and oppressive.

The Municipality assailed the arguments presented by Pepsi Cola. It argued,

among others, that only Ordinance No. 27 is being enforced and that the latter

law is an amendment of Ordinance No. 23, hence there is no double taxation.

ISSUE: Whether or not there is undue delegation of taxing powers. Whether or not

there is double taxation.

HELD: No. There is no undue delegation. The Constitution even allows such

delegation. Legislative powers may be delegated to local governments in respect

of matters of local concern. By necessary implication, the legislative power to

create political corporations for purposes of local self-government carries with it

the power to confer on such local governmental agencies the power to tax.

Under the New Constitution, local governments are granted the autonomous

authority to create their own sources of revenue and to levy taxes. Section 5,

Article XI provides: Each local government unit shall have the power to create its

sources of revenue and to levy taxes, subject to such limitations as may be

provided by law. Withal, it cannot be said that Section 2 of Republic Act No. 2264

emanated from beyond the sphere of the legislative power to enact and vest in

local governments the power of local taxation.

There is no double taxation. The argument of the Municipality is well taken. Further,

Pepsi Colas assertion that the delegation of taxing power in itself constitutes

double taxation cannot be merited. It must be observed that the delegating

authority specifies the limitations and enumerates the taxes over which local

taxation may not be exercised. The reason is that the State has exclusively

reserved the same for its own prerogative. Moreover, double taxation, in general,

is not forbidden by our fundamental law unlike in other jurisdictions. Double

taxation becomes obnoxious only where the taxpayer is taxed twice for the

benefit of the same governmental entity or by the same jurisdiction for the same

purpose, but not in a case where one tax is imposed by the State and the other

by the city or municipality.

DIGEST2

PEPSI-COLA BOTTLING CO. OF THE PHILS., INC. vs. MUNICIPALITY OF TANAUAN

69 SCRA 460

GR No. L-31156, February 27, 1976

"Legislative power to create political corporations for purposes of local self-

government carries with it the power to confer on such local governmental

agencies the power to tax.

FACTS: Plaintiff-appellant Pepsi-Cola commenced a complaint with preliminary

injunction to declare Section 2 of Republic Act No. 2264, otherwise known as the

Local Autonomy Act, unconstitutional as an undue delegation of taxing authority

as well as to declare Ordinances Nos. 23 and 27 denominated as "municipal

production tax" of the Municipality of Tanauan, Leyte, null and void. Ordinance 23

levies and collects from soft drinks producers and manufacturers a tax of one-

sixteenth (1/16) of a centavo for every bottle of soft drink corked, and Ordinance

27 levies and collects on soft drinks produced or manufactured within the territorial

jurisdiction of this municipality a tax of ONE CENTAVO (P0.01) on each gallon (128

fluid ounces, U.S.) of volume capacity. Aside from the undue delegation of

authority, appellant contends that it allows double taxation, and that the subject

ordinances are void for they impose percentage or specific tax.

ISSUE: Are the contentions of the appellant tenable?

HELD: No. On the issue of undue delegation of taxing power, it is settled that the

power of taxation is an essential and inherent attribute of sovereignty, belonging

5

as a matter of right to every independent government, without being expressly

conferred by the people. It is a power that is purely legislative and which the

central legislative body cannot delegate either to the executive or judicial

department of the government without infringing upon the theory of separation of

powers. The exception, however, lies in the case of municipal corporations, to

which, said theory does not apply. Legislative powers may be delegated to local

governments in respect of matters of local concern. By necessary implication, the

legislative power to create political corporations for purposes of local self-

government carries with it the power to confer on such local governmental

agencies the power to tax.

Also, there is no validity to the assertion that the delegated authority can be

declared unconstitutional on the theory of double taxation. It must be observed

that the delegating authority specifies the limitations and enumerates the taxes

over which local taxation may not be exercised. The reason is that the State has

exclusively reserved the same for its own prerogative. Moreover, double taxation,

in general, is not forbidden by our fundamental law, so that double taxation

becomes obnoxious only where the taxpayer is taxed twice for the benefit of the

same governmental entity or by the same jurisdiction for the same purpose, but

not in a case where one tax is imposed by the State and the other by the city or

municipality.

On the last issue raised, the ordinances do not partake of the nature of a

percentage tax on sales, or other taxes in any form based thereon. The tax is

levied on the produce (whether sold or not) and not on the sales. The volume

capacity of the taxpayer's production of soft drinks is considered solely for

purposes of determining the tax rate on the products, but there is not set ratio

between the volume of sales and the amount of the tax.

DIGEST3

The legislative power to create political corporations for purposes of locals el f -

gov er nmen t cou r t s wi t h i t t he power t o conf er on s u ch

l ocal government agencies the power to tax.

Pepsi commenced a compl ai nt wi th prel i mi nary i nj uncti onbefore the

CFI of Leyte for that court to declare Section 2 ofR.A. 2264 (Local Autonomy Act)

unconstitutional as an unduedel egati on of taxi ng authori ty as wel l as

decl are Muni ci pal Ordi nance Nos. 23 & 27 seri es of 1962 of

Muni ci pal i ty of Tanauan, Leyte null and void. Municipal Ordinance 23 leviesand

collects from softdrinks producers and manufacturers atai of 1/16

th

of a centavo

for every bottle of softdrink corked.On t he ot he r hand, Muni ci pal

Or di nance 2 7 l ev i es and col l ects on softdri nks produced or

manufactured wi thi n theterritorial jurisdiction of the municipality a tax of 1

centavoon each gallon of volume capacity. Both are denominated asmunicipal

production tax.Issues: a) WoN section 2 of R.A. 2264 is an undue delegationof

power b) WoN Ordi nances 23 & 27 consti tute doubl etaxati on and

i mpose percentage or speci fi c t ax c) WoNOrdinances 23 and 27 are

unjust and unfairHel d: a) No, i t i s t r ue t hat power of t ax at i on i s

pu r el y l egi sl ati ve and whi ch the central l egi sl ati ve body

cannotdel egate ei ther to the executi ve or j udi ci al department of t he

gov er nmen t wi t hou t i nf r i ngi ng upon t he t heor y of separati on

of powers but the excepti on l i es i n the case ofmuni ci pal corporati ons

to whi ch the sai d theory does not appl y . L egi s l at i ve conce r ns

may be del egat ed t o l ocal governments i n respect of matters of

l ocal concerns. Byne ces s ar y i mpl i cat i on, t he l egi s l at i v e power

t o cr eat e political corporations for purposes of local self-governmentcourts with

it the power to confer on such local governmentagenci es the power to tax.

The consti tuti on grants l ocal government the autonomous authori ty to

create thei r ownsources of revenue and to levy taxes.b) No, the difference

between the two ordinances clearly liesin the tax rate of the soft drinks produced:

in Ordinance No.2 3 , i t was 1 / 1 6 of a cen t av o f or ev e r y bot t l e

cor k ed; i n Ordi nance No. 27, i t i s one centavo (P0.01) on each

gal l on(128 fluid ounces, U.S.) of volume capacity. The intention of

the Municipal Council of Tanauan in enacting Ordinance No.27 is thus clear: it

was intended as a plain substitute for thepr i or Or di nance No. 2 3 , and

ope r at es as a r epeal of t he latter, even without words to that effect.

Plaintiff-appellanti n i ts bri ef admi tted that defendants -appel l ees are

onl ys eek i ng t o enf or ce Or di nance No. 2 7 , s er i es of

1 9 6 2 . Undoubt e dl y , t he t ax i ng au t hor i t y con f er r ed on

l ocal governments under Section 2, Republic Act No. 2264, is broadenough as

to extend to al most " everythi ng, accepti ng thosewhi ch ar e

men t i oned t her ei n. "

T he l i mi t at i on appl i es , parti cul arl y to the prohi bi ti on agai nst

muni ci pal i ti es andmuni ci pal di stri cts to i mpose " any percentage tax

or other taxes in any form based thereon nor impose taxes on articlessubject to

specific tax except gasoline, under the provisionsof the National Internal Revenue

Code." For purposes of thisparticular limitation, a municipal ordinance which

prescribesa set ratio between the amount of the tax and the volume ofsale of the

taxpayer imposes a sales tax and is null and voidf o r b e i n g o u t s i d e t h e

p o w e r o f t h e mu n i c i p a l i t y t o enact. But, the i mposi ti on of " a

tax of one centavo (P0.01) o n e a c h g a l l o n o f v o l u me

c a p a c i t y " o n a l l s o f t d r i n k s produced or manufactured under

6

Ordinance No. 27 does notpartake of the nature of a percentage tax on sales, or

othertaxes i n any form based thereon. The tax i s l evi ed on

theproduce (whether sol d or not) and not on the sal es. Thevolume

capacity of the taxpayer's production of soft drinks isconsidered solely for

purposes of determining the tax rate onthe products, but there is not set ratio

between the volumeof sales and the amount of the tax.

Nor can the tax levied be treated as a specific tax. Specific taxes are those

imposed on specified articles, such as distilled spirits, wines, fermented liquors,

products of tobacco other than cigars and cigarettes, matches fi recrackers,

manufactured oi l s and other fuel s, coal, bunker fuel oil, diesel fuel oil,

cinematographic films, pl ayi ng cards, sacchari ne, opi um and other

habi t-formi ng drugs. Soft drink is not one of those specified. c) The tax of one

(P0.01) on each gal l on (128 fl ui d ounces, U. S . ) of v ol ume

capaci t y on al l s of t dr i nk s , pr odu ced or ma n u f a c t u r e d , o r

a n e q u i v a l e n t o f 1 - c e n t a v o s p e r case, cannot be

considered unjust and unfair. An increasei n the tax al one woul d not support

the cl ai m that the tax i s oppressive, unjust and confiscatory. Municipal

corporations are al l owed much di screti on i n determi ni ng the rates of

imposable taxes. This is in line with the constitutional policy o f a c c o r d i n g

t h e w i d e s t p o s s i b l e a u t o n o m y t o l o c a l governments i n

matters of l ocal taxati on, an aspect that i s gi ven expressi on i n the

Local Tax Code (PD No. 231, Jul y 1, 1973). Unless the amount is so excessive

as to be prohibitive, c o u r t s w i l l g o s l o w i n w r i t i n g o f f

a n o r d i n a n c e a s unreasonable. Reluctance should not deter

compliance with an ordinance such as Ordinance No. 27 if the purpose of the

l aw t o f u r t he r s t r engt hen l ocal au t onomy wer e t o be realized.

DIGEST4

PEPSI-COLA BOTTLING CO. OF THE PHILS., INC. vs. MUNICIPALITY OF TANAUAN

69 SCRA 460

GR No. L-31156, February 27, 1976

"Legislative power to create political corporations for purposes of local self-

government carries with it the power to confer on such local governmental

agencies the power to tax.

FACTS: Plaintiff-appellant Pepsi-Cola commenced a complaint with preliminary

injunction to declare Section 2 of Republic Act No. 2264, otherwise known as the

Local Autonomy Act, unconstitutional as an undue delegation of taxing authority

as well as to declare Ordinances Nos. 23 and 27 denominated as "municipal

production tax" of the Municipality of Tanauan, Leyte, null and void. Ordinance 23

levies and collects from soft drinks producers and manufacturers a tax of one-

sixteenth (1/16) of a centavo for every bottle of soft drink corked, and Ordinance

27 levies and collects on soft drinks produced or manufactured within the territorial

jurisdiction of this municipality a tax of ONE CENTAVO (P0.01) on each gallon (128

fluid ounces, U.S.) of volume capacity. Aside from the undue delegation of

authority, appellant contends that it allows double taxation, and that the subject

ordinances are void for they impose percentage or specific tax.

ISSUE: Are the contentions of the appellant tenable?

HELD: No. On the issue of undue delegation of taxing power, it is settled that the

power of taxation is an essential and inherent attribute of sovereignty, belonging

as a matter of right to every independent government, without being expressly

conferred by the people. It is a power that is purely legislative and which the

central legislative body cannot delegate either to the executive or judicial

department of the government without infringing upon the theory of separation of

powers. The exception, however, lies in the case of municipal corporations, to

which, said theory does not apply. Legislative powers may be delegated to local

governments in respect of matters of local concern. By necessary implication, the

legislative power to create political corporations for purposes of local self-

government carries with it the power to confer on such local governmental

agencies the power to tax.

Also, there is no validity to the assertion that the delegated authority can be

declared unconstitutional on the theory of double taxation. It must be observed

that the delegating authority specifies the limitations and enumerates the taxes

over which local taxation may not be exercised. The reason is that the State has

exclusively reserved the same for its own prerogative. Moreover, double taxation,

in general, is not forbidden by our fundamental law, so that double taxation

becomes obnoxious only where the taxpayer is taxed twice for the benefit of the

same governmental entity or by the same jurisdiction for the same purpose, but

not in a case where one tax is imposed by the State and the other by the city or

municipality.

On the last issue raised, the ordinances do not partake of the nature of a

percentage tax on sales, or other taxes in any form based thereon. The tax is

levied on the produce (whether sold or not) and not on the sales. The volume

capacity of the taxpayer's production of soft drinks is considered solely for

purposes of determining the tax rate on the products, but there is not set ratio

between the volume of sales and the amount of the tax.

7

3.

CIR v Estate of Toda

DIGEST1

CIR v. Estate of Benigno Toda

(Tax evasion)

Facts:

CIC authorized Benigno P. Toda, Jr., President andowner of 99.991% of its issued

and outstanding capital stock,to sell the Cibeles Building and the two parcels of

land onwhich the building stands for an amount of not less than P90million.30

August 1989, Toda purportedly sold the property for P100million to Altonaga, who,

in turn, sold the same property on thesame day to Royal Match Inc. (RMI) for P200

million. Thesetwo transactions were evidenced by Deeds of Absolute

Salenotarized on the same day by the same notary public.For the sale of the

property to RMI, Altonaga paid capital gainstax in the amount of P10 million.On 16

April 1990, CIC filed its corporate annual income taxreturn for the year 1989,

declaring, among other things, its gainfrom the sale of real property in the amount

of P75,728.021.After crediting withholding taxes of P254,497.00, it paidP26,341,207

for its net taxable income of P75,987,725.On 12 July 1990, Toda sold his entire

shares of stocks in CICto Le Hun T. Choa for P12.5 million, as evidenced by a

Deedof Sale of Shares of Stocks.

Issue:

WON this is a case of tax evasion or tax avoidance.

Held/Ratio:

Tax avoidance and tax evasion are the two mostcommon ways used by

taxpayers in escaping from taxation.

Tax avoidance is the tax saving device within the meanssanctioned by law. It

should be used by the taxpayer in goodfaith and at arms length

. Tax evasion is a scheme usedoutside of those lawful means and when availed of,

it usuallysubjects the taxpayer to further or additional civil or criminalliabilities.

Tax evasion connotes the integration of three factors :

(1)

the end to be achieved, i.e., the payment of less than thatknown by the taxpayer

to be legally due, or the non-payment of tax when it is shown that a tax is due;

(2)

an accompanying state of mind which is described as being"evil," in "bad faith,"

"willfull," or "deliberate and not accidental";

(3)

a course of action or failure of action which is unlawful.

All these factors are present in the instant case.

That Altonaga was a mere conduit finds support in theadmission of respondent

.Estate that the sale to him was partof the tax planning scheme of CIC.The

scheme resorted to by CIC in making it appear that there were two sales of the

subject properties, i.e., fromCIC to Altonaga, and then from Altonaga to RMI

cannot beconsidered a legitimate tax planning. It is tainted with fraud.Here, it is

obvious that the objective of the sale toAltonaga was to reduce the amount of

tax to be paid. Thetransfer from him to RMI would result to 5% individual

capitalgains tax, instead of 35% corporate income tax. Altonagassole purpose of

acquiring and transferring title of the propertieson the same day was to create a

tax shelter. Altonaga never controlled the property and did not enjoy the normal

benefitsand burdens of ownership. The sale to him was merely a taxploy, a sham,

and without business purpose and economicsubstance. Doubtless, the execution

of the two sales wascalculated to mislead the BIR with the end in view of

reducingthe consequent income tax liability.In a nutshell, the intermediary

transaction, i.e., thesale of Altonaga, which was prompted more on the

mitigationof tax liabilities than for legitimate business purposesconstitutes tax

evasion.

DIGEST2

G.R. No. 147188. September 14, 2004

Facts:

Cebiles Insurance Corporation authorized Benigno P. Toda, Jr., President and

owner of 99.991% of its issued and outstanding capital stock, to sell the Cibeles

Building and the two parcels of land on which the building stands for an amount

of not less than P90 million.

Toda purportedly sold the property for P100 million to Rafael A. Altonaga.

However, Altonaga in turn, sold the same property on the same day to Royal

8

Match Inc. for P200 million. These two transactions were evidenced by Deeds of

Absolute Sale notarized on the same day by the same notary public.

For the sale of the property to Royal Dutch, Altonaga paid capital gains tax [6%]

in the amount of P10 million.

Issue:

Whether or not the scheme employed by Cibelis Insurance Company

constitutes tax evasion.

Ruling:

Yes! The scheme, explained the Court, resorted to by CIC in making it appear

that there were two sales of the subject properties, i.e., from CIC to Altonaga, and

then from Altonaga to RMI cannot be considered a legitimate tax planning. Such

scheme is tainted with fraud.

Fraud in its general sense, is deemed to comprise anything calculated to

deceive, including all acts, omissions, and concealment involving a breach of

legal or equitable duty, trust or confidence justly reposed, resulting in the damage

to another, or by which an undue and unconscionable advantage is taken of

another.

It is obvious that the objective of the sale to Altonaga was to reduce the

amount of tax to be paid especially that the transfer from him to RMI would then

subject the income to only 5% individual capital gains tax, and not the 35%

corporate income tax. Altonagas sole purpose of acquiring and transferring title

of the subject properties on the same day was to create a tax shelter. Altonaga

never controlled the property and did not enjoy the normal benefits and burdens

of ownership. The sale to him was merely a tax ploy, a sham, and without business

purpose and economic substance. Doubtless, the execution of the two sales was

calculated to mislead the BIR with the end in view of reducing the consequent

income tax liability.

In a nutshell, the intermediary transaction, i.e., the sale of Altonaga, which was

prompted more on the mitigation of tax liabilities than for legitimate business

purposes constitutes one of tax evasion.

Generally, a sale or exchange of assets will have an income tax incidence only

when it is consummated. The incidence of taxation depends upon the substance

of a transaction. The tax consequences arising from gains from a sale of property

are not finally to be determined solely by the means employed to transfer legal

title. Rather, the transaction must be viewed as a whole, and each step from the

commencement of negotiations to the consummation of the sale is relevant. A

sale by one person cannot be transformed for tax purposes into a sale by another

by using the latter as a conduit through which to pass title. To permit the true

nature of the transaction to be disguised by mere formalisms, which exist solely to

alter tax liabilities, would seriously impair the effective administration of the tax

policies of Congress.

To allow a taxpayer to deny tax liability on the ground that the sale was made

through another and distinct entity when it is proved that the latter was merely a

conduit is to sanction a circumvention of our tax laws. Hence, the sale to

Altonaga should be disregarded for income tax purposes. The two sale

transactions should be treated as a single direct sale by CIC to RMI.

9

4.

TOLENTINO v Sec of Finance

DIGEST1

Political Law Origination of Revenue Bills EVAT Amendment by Substitution

Tolentino et al is questioning the constitutionality of RA 7716 otherwise known as

the Expanded Value Added Tax (EVAT) Law. Tolentino averred that this revenue

bill did not exclusively originate from the House of Representatives as required by

Section 24, Article 6 of the Constitution. Even though RA 7716 originated as HB

11197 and that it passed the 3 readings in the HoR, the same did not complete the

3 readings in Senate for after the 1

st

reading it was referred to the Senate Ways &

Means Committee thereafter Senate passed its own version known as Senate Bill

1630. Tolentino averred that what Senate could have done is amend HB 11197 by

striking out its text and substituting it w/ the text of SB 1630 in that way the bill

remains a House Bill and the Senate version just becomes the text (only the text) of

the HB. Tolentino and co-petitioner Roco [however] even signed the said Senate

Bill.

ISSUE: Whether or not EVAT originated in the HoR.

HELD: By a 9-6 vote, the SC rejected the challenge, holding that such

consolidation was consistent with the power of the Senate to propose or concur

with amendments to the version originated in the HoR. What the Constitution

simply means, according to the 9 justices, is that the initiative must come from the

HoR. Note also that there were several instances before where Senate passed its

own version rather than having the HoR version as far as revenue and other such

bills are concerned. This practice of amendment by substitution has always been

accepted. The proposition of Tolentino concerns a mere matter of form. There is

no showing that it would make a significant difference if Senate were to adopt his

over what has been done.

DIGEST2

Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance G.R. No. 115455, August 25, 1994

Facts: The value-added tax (VAT) is levied on the sale, barter or exchange of

goods and properties as well as on the sale or exchange of services. RA 7716

seeks to widen the tax base of the existing VAT system and enhance its

administration by amending the National Internal Revenue Code. There are

various suits challenging the constitutionality of RA 7716 on various grounds.

One contention is that RA 7716 did not originate exclusively in the House of

Representatives as required by Art. VI, Sec. 24 of the Constitution, because it is in

fact the result of the consolidation of 2 distinct bills, H. No. 11197 and S. No. 1630.

There is also a contention that S. No. 1630 did not pass 3 readings as required by

the Constitution.

Issue: Whether or not RA 7716 violates Art. VI, Secs. 24 and 26(2) of the Constitution

Held: The argument that RA 7716 did not originate exclusively in the House of

Representatives as required by Art. VI, Sec. 24 of the Constitution will not bear

analysis. To begin with, it is not the law but the revenue bill which is required by the

Constitution to originate exclusively in the House of Representatives. To insist that a

revenue statute and not only the bill which initiated the legislative process

culminating in the enactment of the law must substantially be the same as the

House bill would be to deny the Senates power not only to concur with

amendments but also to propose amendments. Indeed, what the Constitution

simply means is that the initiative for filing revenue, tariff or tax bills, bills authorizing

an increase of the public debt, private bills and bills of local application must

come from the House of Representatives on the theory that, elected as they are

from the districts, the members of the House can be expected to be more

sensitive to the local needs and problems. Nor does the Constitution prohibit the

filing in the Senate of a substitute bill in anticipation of its receipt of the bill from the

House, so long as action by the Senate as a body is withheld pending receipt of

the House bill.

The next argument of the petitioners was that S. No. 1630 did not pass 3 readings

on separate days as required by the Constitution because the second and third

readings were done on the same day. But this was because the President had

certified S. No. 1630 as urgent. The presidential certification dispensed with the

requirement not only of printing but also that of reading the bill on separate days.

That upon the certification of a bill by the President the requirement of 3 readings

on separate days and of printing and distribution can be dispensed with is

supported by the weight of legislative practice.

DIGEST3

Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance,

(235 SCRA 630, 249 SCRA 628)

August 25, 1994; October 30, 1995

10

Facts:

There are various suits challenging the constitutionality of RA 7716 on

variousgrounds.The value-added tax (VAT) is levied on the sale, barter or

exchange of goodsand properties as well as on the sale or exchange of services.

It is equivalent to 10% of the gross selling price or gross value in money of goods or

properties sold, bartered or exchanged or of the gross receipts from the sale or

exchange of services. Republic ActNo. 7716 seeks to widen the tax base of the

existing VAT system and enhance itsadministration by amending the National

Internal Revenue Code. Among the Petitioners was the Philippine Press Institute

which claim that R.A.7716 violates their press freedom and religious liberty, having

removed them from theexemption to pay Value Added Tax. It is contended by

the PPI that by removing theexemption of the press from the VAT while

maintaining those granted to others, the lawdiscriminates against the press. At any

rate, it is averred, "even nondiscriminatorytaxation of constitutionally guaranteed

freedom is unconstitutional." PPI argued that theVAT is in the nature of a license

tax.

Issue:

Whether or not the purpose of the VAT is the same as that of a license tax.

Ruling:

A license tax, which, unlike an ordinary tax, is mainly for regulation. Its

impositionon the press is unconstitutional because it lays a prior restraint on the

exercise of itsright. Hence, although its application to others, such those selling

goods, is valid, itsapplication to t

he press or to religious groups, such as the Jehovahs Witnesses, inconnection with the latters sale of

religious books and pamphlets, is unconstitutional. As the U.S. Supreme Court put it, it is one

thing to impose a tax on income or property of a preacher. It is quite another thing to

exact a tax on him for delivering a sermon.

The VAT is, however, different.

It is not a license tax.

It is not a tax on theexercise of a privilege, much less a constitutional right. It is

imposed on the sale, barter,lease or exchange of goods or properties or the sale

or exchange of services and thelease of properties purely for revenue purposes.

To subject the press to its payment isnot to burden the exercise of its right any

more than to make the press pay income taxor subject it to general regulation is

not to violate its freedom under the Constitution.

DIGEST4

Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance

Facts: These are motions seeking reconsideration of our decision dismissing the

petitions filed inthese cases for the declaration of unconstitutionality of R.A. No.

7716, otherwise known as theExpanded Value-Added Tax Law. Now it is

contended by the PPI that by removing the exemption of the press from the VAT

while maintaining those granted to others, the law discriminates against the press.

At any rate, it is averred, "even nondiscriminatory taxation of constitutionally

guaranteedfreedom is unconstitutional."Issue: Does sales tax on bible sales

violative of religious freedom?Held: No. The Court was speaking in that case of a

license tax, which, unlike an ordinary tax, is mainly for regulation. Its imposition on

the press is unconstitutional because it lays a prior restraint on the exercise of its

right. Hence, although its application to others, such those selling goods, is valid, its

application to the press or to religious groups, such as the Jehovah's Witnesses, in

connection with the latter's sale of religious books and pamphlets, is

unconstitutional. As the U.S. Supreme Court put it, "it is one thing to impose a tax

on income or property of a preacher. It is quiteanother thing to exact a tax on him

for delivering a sermon."The VAT is, however, different. It is not a license tax. It is not

a tax on the exercise of a privilege,much less a constitutional right. It is imposed on

the sale, barter, lease or exchange of goods or properties or the sale or exchange

of services and the lease of properties purely for revenuepurposes. To subject the

press to its payment is not to burden the exercise of its right any more than to

make the press pay income tax or subject it to general regulation is not to violate

its freedomunder the Constitution

DIGEST5

FACTS

RA 7716, otherwise known as the Expanded Value-Added Tax Law, is an act that

seeks to widen the tax base of the existing VAT system and enhance its

administration by amending the National Internal Revenue Code. There are

various suits questioning and challenging the constitutionality of RA 7716 on

various grounds.

Tolentino contends that RA 7716 did not originate exclusively from the House of

Representatives but is a mere consolidation of HB. No. 11197 and SB. No. 1630 and

it did not pass three readings on separate days on the Senate thus violating Article

VI, Sections 24 and 26(2) of the Constitution, respectively.

11

Art. VI, Section 24: All appropriation, revenue or tariff bills, bills authorizing increase

of the public debt, bills of local application, and private bills shall originate

exclusively in the House of Representatives, but the Senate may propose or

concur with amendments.

Art. VI, Section 26(2): No bill passed by either House shall become a law unless it

has passed three readings on separate days, and printed copies thereof in its final

form have been distributed to its Members three days before its passage, except

when the President certifies to the necessity of its immediate enactment to meet a

public calamity or emergency. Upon the last reading of a bill, no amendment

thereto shall be allowed, and the vote thereon shall be taken immediately

thereafter, and the yeas and nays entered in the Journal.

ISSUE

Whether or not RA 7716 violated Art. VI, Section 24 and Art. VI, Section 26(2) of the

Constitution.

HELD

No. The phrase originate exclusively refers to the revenue bill and not to the

revenue law. It is sufficient that the House of Representatives initiated the passage

of the bill which may undergo extensive changes in the Senate.

SB. No. 1630, having been certified as urgent by the President need not meet the

requirement not only of printing but also of reading the bill on separate days.

12

5

Abakada Guro Party List, et al vs Exec. Sec. Ermita

DIGEST1

Facts: On May 24, 2005, the President signed into law Republic Act 9337 or the VAT

Reform Act. Before the law took effect on July 1, 2005, the Court issued a TRO

enjoining government from implementing the law in response to a slew of petitions

for certiorari and prohibition questioning the constitutionality of the new law.

The challenged section of R.A. No. 9337 is the common proviso in Sections 4, 5 and

6: That the President, upon the recommendation of the Secretary of Finance,

shall, effective January 1, 2006, raise the rate of value-added tax to 12%, after any

of the following conditions has been satisfied:

(i) Value-added tax collection as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

of the previous year exceeds two and four-fifth percent (2 4/5%);

or (ii) National government deficit as a percentage of GDP of the previous year

exceeds one and one-half percent (1%)

Petitioners allege that the grant of stand-by authority to the President to increase

the VAT rate is an abdication by Congress of its exclusive power to tax because

such delegation is not covered by Section 28 (2), Article VI Consti. They argue that

VAT is a tax levied on the sale or exchange of goods and services which cant be

included within the purview of tariffs under the exemption delegation since this

refers to customs duties, tolls or tribute payable upon merchandise to the

government and usually imposed on imported/exported goods. They also said

that the President has powers to cause, influence or create the conditions

provided by law to bring about the conditions precedent. Moreover, they allege

that no guiding standards are made by law as to how the Secretary of Finance

will make the recommendation.

Issue: Whether or not the RA 9337's stand-by authority to the Executive to increase

the VAT rate, especially on account of the recommendatory power granted to

the Secretary of Finance, constitutes undue delegation of legislative power? NO

Held: The powers which Congress is prohibited from delegating are those which

are strictly, or inherently and exclusively, legislative. Purely legislative power which

can never be delegated is the authority to make a complete law- complete as to

the time when it shall take effect and as to whom it shall be applicable, and to

determine the expediency of its enactment. It is the nature of the power and not

the liability of its use or the manner of its exercise which determines the validity of

its delegation.

The exceptions are:

(a) delegation of tariff powers to President under Constitution

(b) delegation of emergency powers to President under Constitution

(c) delegation to the people at large

(d) delegation to local governments

(e) delegation to administrative bodies

For the delegation to be valid, it must be complete and it must fix a standard. A

sufficient standard is one which defines legislative policy, marks its limits, maps out

its boundaries and specifies the public agency to apply it.

In this case, it is not a delegation of legislative power BUT a delegation of

ascertainment of facts upon which enforcement and administration of the

increased rate under the law is contingent. The legislature has made the

operation of the 12% rate effective January 1, 2006, contingent upon a specified

fact or condition. It leaves the entire operation or non-operation of the 12% rate

upon factual matters outside of the control of the executive. No discretion would

be exercised by the President. Highlighting the absence of discretion is the fact

that the word SHALL is used in the common proviso. The use of the word SHALL

connotes a mandatory order. Its use in a statute denotes an imperative obligation

and is inconsistent with the idea of discretion.

Thus, it is the ministerial duty of the President to immediately impose the 12% rate

upon the existence of any of the conditions specified by Congress. This is a duty,

which cannot be evaded by the President. It is a clear directive to impose the 12%

VAT rate when the specified conditions are present.

Congress just granted the Secretary of Finance the authority to ascertain the

existence of a fact--- whether by December 31, 2005, the VAT collection as a

percentage of GDP of the previous year exceeds 2 4/5 % or the national

13

government deficit as a percentage of GDP of the previous year exceeds one

and 1%. If either of these two instances has occurred, the Secretary of Finance,

by legislative mandate, must submit such information to the President.

In making his recommendation to the President on the existence of either of the

two conditions, the Secretary of Finance is not acting as the alter ego of the

President or even her subordinate. He is acting as the agent of the legislative

department, to determine and declare the event upon which its expressed will is

to take effect. The Secretary of Finance becomes the means or tool by which

legislative policy is determined and implemented, considering that he possesses

all the facilities to gather data and information and has a much broader

perspective to properly evaluate them. His function is to gather and collate

statistical data and other pertinent information and verify if any of the two

conditions laid out by Congress is present.

Congress does not abdicate its functions or unduly delegate power when it

describes what job must be done, who must do it, and what is the scope of his

authority; in our complex economy that is frequently the only way in which the

legislative process can go forward.

There is no undue delegation of legislative power but only of the discretion as to

the execution of a law. This is constitutionally permissible. Congress did not

delegate the power to tax but the mere implementation of the law.

DIGEST2

ABAKADA Guro Party List vs. Ermita

G.R. No. 168056 September 1, 2005

FACTS:

Before R.A. No. 9337 took effect, petitioners ABAKADA GURO Party List, et al., filed

a petition for prohibition on May 27, 2005 questioning the constitutionality of

Sections 4, 5 and 6 of R.A. No. 9337, amending Sections 106, 107 and 108,

respectively, of the National Internal Revenue Code (NIRC). Section 4 imposes a

10% VAT on sale of goods and properties, Section 5 imposes a 10% VAT on

importation of goods, and Section 6 imposes a 10% VAT on sale of services and

use or lease of properties. These questioned provisions contain a uniformp ro v is o

authorizing the President, upon recommendation of the Secretary of Finance, to

raise the VAT rate to 12%, effective January 1, 2006, after specified conditions

have been satisfied. Petitioners argue that the law is unconstitutional.

ISSUES:

1. Whether or not there is a violation of Article VI, Section 24 of the Constitution.

2. Whether or not there is undue delegation of legislative power in violation of

Article VI Sec 28(2) of the Constitution.

3. Whether or not there is a violation of the due process and equal protection

under Article III Sec. 1 of the Constitution.

RULING:

1. Since there is no question that the revenue bill exclusively originated in the

House of Representatives, the Senate was acting within its constitutional power to

introduce amendments to the House bill when it included provisions in Senate Bill

No. 1950 amending corporate income taxes, percentage, and excise and

franchise taxes.

2. There is no undue delegation of legislative power but only of the discretion as to

the execution of a law. This is constitutionally permissible. Congress does not

abdicate its functions or unduly delegate power when it describes what job must

be done, who must do it, and what is the scope of his authority; in our complex

economy that is frequently the only way in which the legislative process can go

forward.

3. The power of the State to make reasonable and natural classifications for the

purposes of taxation has long been established. Whether it relates to the subject

of taxation, the kind of property, the rates to be levied, or the amounts to be

raised, the methods of assessment, valuation and collection, the States power is

entitled to presumption of validity. As a rule, the judiciary will not interfere with

such power absent a clear showing of unreasonableness, discrimination, or

arbitrariness.

DIGEST3

Facts:

Motions for Reconsideration filed by petitioners, ABAKADA Guro party List Officer

and et al., insist that the bicameral conference committee should not even have

acted on the no pass-on provisions since there is no disagreement between House

14

Bill Nos. 3705 and 3555 on the one hand, and Senate Bill No. 1950 on the other,

with regard to the no pass-on provision for the sale of service for power generation

because both the Senate and the House were in agreement that the VAT burden

for the sale of such service shall not be passed on to the end-consumer. As to the

no pass-on provision for sale of petroleum products, petitioners argue that the fact

that the presence of such a no pass-on provision in the House version and the

absence thereof in the Senate Bill means there is no conflict because a House

provision cannot be in conflict with something that does not exist.

Escudero, et. al., also contend that Republic Act No. 9337 grossly violates the

constitutional imperative on exclusive origination of revenue bills under Section 24

of Article VI of the Constitution when the Senate introduced amendments not

connected with VAT.

Petitioners Escudero, et al., also reiterate that R.A. No. 9337s stand- by authority to

the Executive to increase the VAT rate, especially on account of the

recommendatory power granted to the Secretary of Finance, constitutes undue

delegation of legislative power. They submit that the recommendatory power

given to the Secretary of Finance in regard to the occurrence of either of two

events using the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a benchmark necessarily and

inherently required extended analysis and evaluation, as well as policy making.

Petitioners also reiterate their argument that the input tax is a property or a

property right. Petitioners also contend that even if the right to credit the input VAT

is merely a statutory privilege, it has already evolved into a vested right that the

State cannot remove.

Issue:

Whether or not the R.A. No. 9337 or the Vat Reform Act is constitutional?

Held:

The Court is not persuaded. Article VI, Section 24 of the Constitution provides that

All appropriation, revenue or tariff bills, bills authorizing increase of the public debt,

bills of local application, and private bills shall originate exclusively in the House of

Representatives, but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments.

The Court reiterates that in making his recommendation to the President on the

existence of either of the two conditions, the Secretary of Finance is not acting as

the alter ego of the President or even her subordinate. He is acting as the agent of

the legislative department, to determine and declare the event upon which its

expressed will is to take effect. The Secretary of Finance becomes the means or

tool by which legislative policy is determined and implemented, considering that

he possesses all the facilities to gather data and information and has a much

broader perspective to properly evaluate them. His function is to gather and

collate statistical data and other pertinent information and verify if any of the two

conditions laid out by Congress is present.

In the same breath, the Court reiterates its finding that it is not a property or a

property right, and a VAT-registered persons entitlement to the creditable input

tax is a mere statutory privilege. As the Court stated in its Decision, the right to

credit the input tax is a mere creation of law. More importantly, the assailed

provisions of R.A. No. 9337 already involve legislative policy and wisdom. So long

as there is a public end for which R.A. No. 9337 was passed, the means through

which such end shall be accomplished is for the legislature to choose so long as it

is within constitutional bounds.

The Motions for Reconsideration are hereby DENIED WITH FINALITY. The temporary

restraining order issued by the Court is LIFTED.

DIGEST4

ABAKADA GURO PARTY LIST V. ERMITA

September 1, 2005

AUSTRIA-MARTINEZ, J

>>>THE VAT REFORM LAW (RA 9337) IS ENTIRELY CONSTITUTIONAL

NATURE OF VAT

The VAT is a tax on spending or consumption. It is levied on the sale, barter,

exchange or lease of goods or properties and services. Being an indirect tax on

expenditure, the seller of goods or services may pass on the amount of tax paid to

the buyer, with the seller acting merely as a tax collector. The burden of VAT is

intended to fall on the immediate buyers and ultimately, the end-consumers.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In the Philippines, the value-added system of sales taxation has long been in

existence, albeit in a different mode. Prior to 1978, the system was a single-stage

15

tax computed under the "cost deduction method" and was payable only by the

original sellers. The single-stage system was subsequently modified, and a mixture

of the "cost deduction method" and "tax credit method" was used to determine

the value-added tax payable. Under the "tax credit method," an entity can credit

against or subtract from the VAT charged on its sales or outputs the VAT paid on its

purchases, inputs and imports.

It was only in 1987, when President Corazon C. Aquino issued Executive Order No.

273, that the VAT system was rationalized by imposing a multi-stage tax rate of 0%

or 10% on all sales using the "tax credit method."

E.O. No. 273 was followed by R.A. No. 7716 or the Expanded VAT Law, R.A. No.

8241 or the Improved VAT Law, R.A. No. 8424 or the Tax Reform Act of 1997, and

finally, the presently beleaguered R.A. No. 9337, also referred to by respondents as

the VAT Reform Act.

ENROLLED BILL DOCTRINE

Under the "enrolled bill doctrine," the signing of a bill by the Speaker of the House

and the Senate President and the certification of the Secretaries of both Houses of

Congress that it was passed are conclusive of its due enactment.

COURTS GENERALLY DENIED THE POWER TO INQUIRE INTO CONGRESS FAILURE TO

COMPLY WITH ITS OWN RULES

The cases, both here and abroad, in varying forms of expression, all deny to the

courts the power to inquire into allegations that, in enacting a law, a House of

Congress failed to comply with its own rules, in the absence of showing that there

was a violation of a constitutional provision or the rights of private individuals. In

Osmea v. Pendatun, it was held: "At any rate, courts have declared that 'the

rules adopted by deliberative bodies are subject to revocation, modification or

waiver at the pleasure of the body adopting them.' And it has been said that

"Parliamentary rules are merely procedural, and with their observance, the courts

have no concern. They may be waived or disregarded by the legislative body."

The foregoing declaration is exactly in point with the present cases, where

petitioners allege irregularities committed by the conference committee in

introducing changes or deleting provisions in the House and Senate bills. One of

the most basic and inherent power of the legislature is the power to formulate

rules for its proceedings and the discipline of its members. Congress is the best

judge of how it should conduct its own business expeditiously and in the most

orderly manner. It is also the sole concern of Congress to instill discipline among

the members of its conference committee if it believes that said members violated

any of its rules of proceedings. Even the expanded jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court cannot apply to questions regarding only the internal operation of

Congress.

BICAMERAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE (BCC)

All the changes or modifications made by the Bicameral Conference Committee

were germane to subjects of the provisions referred to it for reconciliation. Such

being the case, the Court does not see any grave abuse of discretion amounting

to lack or excess of jurisdiction committed by the Bicameral Conference

Committee. The Court recognized the long-standing legislative practice of giving

said conference committee ample latitude for compromising differences

between the Senate and the House. Thus, in the Tolentino case, it was held that:

. . . it is within the power of a conference committee to include in its report an

entirely new provision that is not found either in the House bill or in the Senate bill. If

the committee can propose an amendment consisting of one or two provisions,

there is no reason why it cannot propose several provisions, collectively

considered as an "amendment in the nature of a substitute," so long as such

amendment is germane to the subject of the bills before the committee. After all,

its report was not final but needed the approval of both houses of Congress to

become valid as an act of the legislative department. The charge that in this case

the Conference Committee acted as a third legislative chamber is thus without

any basis.

NO AMENDEMENT RULE NOT VIOLATED BY BCC

Article VI, Sec. 26 (2) of the Constitution, states:

No bill passed by either House shall become a law unless it has passed three

readings on separate days, and printed copies thereof in its final form have been

distributed to its Members three days before its passage, except when the

President certifies to the necessity of its immediate enactment to meet a public

calamity or emergency. Upon the last reading of a bill, no amendment thereto

shall be allowed, and the vote thereon shall be taken immediately thereafter, and

the yeas and nays entered in the Journal.

There is no reason for requiring that the Committee's Report in these cases must

have undergone three readings in each of the two houses. If that be the case,

there would be no end to negotiation since each house may seek modification of

16

the compromise bill. . . .

EXTENT OF NO AMENDMENT RULE

The No Amendment Rule must be construed as referring only to bills introduced

for the first time in either house of Congress, not to the conference committee

report.

BILLS WHICH MUST EXCLUSIVELY ORIGINATE IN THE HOUSE

All appropriation, revenue or tariff bills, bills authorizing increase of the public debt,

bills of local application, and private bills shall originate exclusively in the House of

Representatives but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments.

In the present cases, petitioners admit that it was indeed House Bill Nos. 3555 and

3705 that initiated the move for amending provisions of the NIRC dealing mainly

with the value-added tax. Upon transmittal of said House bills to the Senate, the

Senate came out with Senate Bill No. 1950 proposing amendments not only to

NIRC provisions on the value-added tax but also amendments to NIRC provisions

on other kinds of taxes. Is the introduction by the Senate of provisions not dealing

directly with the value-added tax, which is the only kind of tax being amended in

the House bills, still within the purview of the constitutional provision authorizing the

Senate to propose or concur with amendments to a revenue bill that originated

from the House?

YES. In the Tolentino case:

. . . To begin with, it is not the law but the revenue bill which is required by

the Constitution to "originate exclusively" in the House of Representatives. It is

important to emphasize this, because a bill originating in the House may undergo

such extensive changes in the Senate that the result may be a rewriting of the

whole. . . . At this point, what is important to note is that, as a result of the Senate

action, a distinct bill may be produced. To insist that a revenue statute and not

only the bill which initiated the legislative process culminating in the enactment of

the law must substantially be the same as the House bill would be to deny the

Senate's power not only to "concur with amendments" but also to "propose

amendments." It would be to violate the coequality of legislative power of the two

houses of Congress and in fact make the House superior to the Senate.

Indeed, what the Constitution simply means is that the initiative for filing revenue,

tariff or tax bills, bills authorizing an increase of the public debt, private bills and

bills of local application must come from the House of Representatives on the

theory that, elected as they are from the districts, the members of the House can

be expected to be more sensitive to the local needs and problems. On the other

hand, the senators, who are elected at large, are expected to approach the

same problems from the national perspective. Both views are thereby made to

bear on the enactment of such laws.

NON-DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE POWER

The principle of separation of powers ordains that each of the three great

branches of government has exclusive cognizance of and is supreme in matters

falling within its own constitutionally allocated sphere. A logical corollary to the

doctrine of separation of powers is the principle of non-delegation of powers, as

expressed in the Latin maxim: potestas delegata non delegari potest which

means "what has been delegated, cannot be delegated." This doctrine is based

on the ethical principle that such as delegated power constitutes not only a right

but a duty to be performed by the delegate through the instrumentality of his own

judgment and not through the intervening mind of another.

The powers which Congress is prohibited from delegating are those which are

strictly, or inherently and exclusively, legislative. Purely legislative power, which can

never be delegated, has been described as the authority to make a complete

law complete as to the time when it shall take effect and as to whom it shall be

applicable and to determine the expediency of its enactment. Thus, the rule is

that in order that a court may be justified in holding a statute unconstitutional as a

delegation of legislative power, it must appear that the power involved is purely

legislative in nature that is, one appertaining exclusively to the legislative

department. It is the nature of the power, and not the liability of its use or the

manner of its exercise, which determines the validity of its delegation.

EXCEPTIONS:

(1) Delegation of tariff powers to the President under Section 28 (2) of Article VI of

the Constitution;

(2) Delegation of emergency powers to the President under Section 23 (2) of

Article VI of the Constitution;

(3) Delegation to the people at large;

(4) Delegation to local governments; and

(5) Delegation to administrative bodies.

In every case of permissible delegation, there must be a showing that the

17

delegation itself is valid. It is valid only if the law (a) is complete in itself, setting

forth therein the policy to be executed, carried out, or implemented by the

delegate; and (b) fixes a standard the limits of which are sufficiently

determinate and determinable to which the delegate must conform in the

performance of his functions. A sufficient standard is one which defines legislative

policy, marks its limits, maps out its boundaries and specifies the public agency to

apply it.

NO DELEGATION OF LEGISLATIVE POWER TO THE PRESIDENT IN THIS CASE

In the present case, the challenged section of R.A. No. 9337 is the common

proviso in Sections 4, 5 and 6 which reads as follows:

That the President, upon the recommendation of the Secretary of Finance, shall,

effective January 1, 2006, raise the rate of value-added tax to twelve percent

(12%), after any of the following conditions has been satisfied: xxx

The case is not a delegation of legislative power. It is simply a delegation of

ascertainment of facts upon which enforcement and administration of the

increase rate under the law is contingent. The legislature has made the operation

of the 12% rate effective January 1, 2006, contingent upon a specified fact or

condition. It leaves the entire operation or non-operation of the 12% rate upon

factual matters outside of the control of the executive. No discretion would be

exercised by the President. Highlighting the absence of discretion is the fact that

the word shall is used in the common proviso. The use of the word shall connotes a

mandatory order. Its use in a statute denotes an imperative obligation and is

inconsistent with the idea of discretion.

SECRETARY OF FINANCE AS AGENT OF LEGISLATURE; PRESIDENTS POWER OF

CONTROL NOT APPLICABLE

In the present case, in making his recommendation to the President on the

existence of either of the two conditions, the Secretary of Finance is not acting as

the alter ego of the President or even her subordinate. In such instance, he is not

subject to the power of control and direction of the President. He is acting as the

agent of the legislative department, to determine and declare the event upon

which its expressed will is to take effect. The Secretary of Finance becomes the

means or tool by which legislative policy is determined and implemented,

considering that he possesses all the facilities to gather data and information and

has a much broader perspective to properly evaluate them. His function is to

gather and collate statistical data and other pertinent information and verify if

any of the two conditions laid out by Congress is present. His personality in such

instance is in reality but a projection of that of Congress. Thus, being the agent of

Congress and not of the President, the President cannot alter or modify or nullify,

or set aside the findings of the Secretary of Finance and to substitute the judgment

of the former for that of the latter.

NO VIOLATION OF PRINCIPLE OF REPUBLICANISM

As to the argument of petitioners that delegating to the President the legislative

power to tax is contrary to the principle of republicanism, the same deserves scant

consideration. Congress did not delegate the power to tax but the mere

implementation of the law. The intent and will to increase the VAT rate to 12%

came from Congress and the task of the President is to simply execute the

legislative policy. That Congress chose to do so in such a manner is not within the

province of the Court to inquire into, its task being to interpret the law.

NEW TAX NOT OPPRESSIVE

The principle of fiscal adequacy as a characteristic of a sound tax system was

originally stated by Adam Smith in his Canons of Taxation (1776). It simply means

that sources of revenues must be adequate to meet government expenditures

and their variations. The dire need for revenue cannot be ignored. Our country is

in a quagmire of financial woe. During the Bicameral Conference Committee

hearing, then Finance Secretary Purisima bluntly depicted the country's gloomy

state of economic affairs.

. . . policy matters are not the concern of the Court. Government policy is within

the exclusive dominion of the political branches of the government. It is not for this

Court to look into the wisdom or propriety of legislative determination. Indeed,

whether an enactment is wise or unwise, whether it is based on sound economic

theory, whether it is the best means to achieve the desired results, whether, in

short, the legislative discretion within its prescribed limits should be exercised in a

particular manner are matters for the judgment of the legislature, and the serious

conflict of opinions does not suffice to bring them within the range of judicial

cognizance.

NO DEPRIVATION OF PROPERTY WITHOUT DUE PROCESS

Petitioners argue that the input tax partakes the nature of a property that may not

be confiscated, appropriated, or limited without due process of law.

18

The input tax is not a property or a property right within the constitutional purview